Abstract

Identification and description of genetic variation underlying disease susceptibility, efficacy, and adverse reactions to drugs remains a difficult problem. One of the important steps in the analysis of variation in a candidate region is the characterization of linkage disequilibrium (LD). In a region of genetic association, the extent of LD varies between the case and the control groups. Separate plots of pairwise standardized measures of LD (e.g., D′) for cases and controls are often presented for a candidate region, to graphically convey case-control differences in LD. However, the observed graphic differences lack statistical support. Therefore, we suggest the “LD contrast” test to compare whole matrices of disequilibrium between two samples. A common technique of assessing LD when the haplotype phase is unobserved is the expectation-maximization algorithm, with the likelihood incorporating the assumption of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). This approach presents a potential problem in that, in the region of genetic association, the HWE assumption may not hold when samples are selected on the basis of phenotypes. Here, we present a computationally feasible approach that does not assume HWE, along with graphic displays and a statistical comparison of pairwise matrices of LD between case and control samples. LD-contrast tests provide a useful addition to existing tools of finding and characterizing genetic associations. Although haplotype association tests are expected to provide superior power when susceptibilities are primarily determined by haplotypes, the LD-contrast tests demonstrate substantially higher power under certain haplotype-driven disease models.

There has been considerable progress in designing techniques that go beyond sequential testing of SNPs. These methods are particularly important for the analysis of multiple SNPs that jointly represent variation within common transcripts and other functional regions, such as promoters. Methods for detection of association between traits and interacting genetic polymorphisms are being rapidly developed. Many approaches have considered important situations in which haplotypes of consecutive markers can be defined and tested for association with the trait. Methods have been designed to incorporate various sampling designs as well as the haplotype phase uncertainty.1–7

It has been noted that the extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) can be different between the case and the control groups in a region of genetic association, and the case-control LD comparison can aid the analysis in a region of putative association.8 Contrasting pairwise LD matrices between cases and controls via graphic display provides a direct visual comparison.9 However, the observed graphic difference is subject to sampling variation and lacks statistical support. Therefore, a statistical test is desirable. In the context of association mapping, Nielsen et al. presented a directLD comparison approach involving two diallelic loci and noted that, in certain situations, a test that directly compares LD extent between the case and the control groups can be a powerful alternative to either haplotype-based or single-marker approaches.10 A test comparing the LD extent will include only a single LD parameter that results in a 1-df test, whereas a haplotype test will include four haplotypes with 3 df. Nielsen et al. considered the case of unambiguous haplotype phase. When the haplotype phase is unknown, the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm is used to infer frequencies of haplotypes and, ultimately, to assess LD. The likelihood is constructed by assuming HWE on the level of haplotypes. With two diallelic markers, there are four haplotypes, and the usual assumption is that the two-locus haplotypes are in HWE. Checking that each SNP is in HWE is not sufficient to ensure HWE at the haplotypic level. Furthermore, in the region of association, the HWE is generally expected to be distorted in case and control samples.11,12 Therefore, the EM computation, although a valuable tool for evaluating LD in a sample of population controls, is not strictly appropriate for comparing LD levels in samples of cases and controls or for samples otherwise selected on the basis of phenotype.

Recently, Schaid13 and Zaykin14 showed that LD estimation with use of the composite disequilibrium approach, discussed below, provides results similar to those of the EM-based method under HWE, is computationally simpler, and avoids the assumption of haplotypic HWE. Hamilton and Cole15 and Zaykin14 gave bounds and proposed normalization for LD based on the composite definition. Zaykin showed that this normalization is robust to departures from HWE. Therefore, we propose use of the composite coefficient and its normalization for characterizing the LD in case-control samples. This leads to efficient methods of comparing and testing the difference of pairwise LD matrices between the case and control samples. We show that certain disease models result in high power of the LD-contrast test in comparison with the haplotypic test, even under situations when susceptibilities are largely determined by haplotypes. In such situations, the LD contrast test outperforms both the haplotype-based test and multilocus tests based on comparison of SNP scores.

Methods

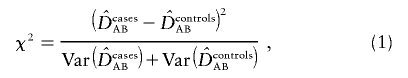

A test for comparing two single LD coefficients (“LD contrast” test) was described by Nielsen et al. for the case of known phase—that is, when four haplotype classes are directly observed.10 A χ2 test statistic has the form

|

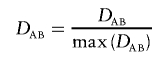

with the variances given by Weir.16(p113) The LD coefficient, DAB, is equal to PAB-pApB, where PAB is the frequency of haplotype carrying alleles A and B and pA and pB are the corresponding allele frequencies. A log-linear framework for comparing disequilibria coefficients at one and two loci has been provided by Huttley and Wilson.17 There is only a single LD parameter describing dependence among the four haplotypes and the corresponding allele frequencies. Therefore, this LD-contrast test has an advantage of being a 1-df test, whereas a haplotypic test with all four haplotypes has 3 df. Nielsen et al. found empirically that this test can have higher power than either a haplotypic or a single-marker test when the pairwise LD between a functional site and two tested markers is low. When the haplotype phase is unknown, the above test can be extended to compare two composite LD coefficients with a test analogous to equation (1), with the variances provided by Weir.16 Furthermore, comparison of standardized coefficients may be of interest when single-locus genotypic frequencies differ. One of the commonly used standardized measures of LD is the coefficient D′AB, suggested by Lewontin,18 where max(DAB) is the maximum possible absolute value of

|

given allele frequencies, also described in a nongenetic context by Yule,19 as

|

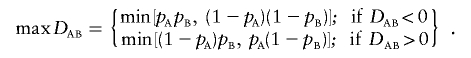

Weir20 discussed the correlation between alleles A and B, given as

|

which has the range that depends on allele frequencies. Weir20 and Peduzzi et al.21 gave the bounds for ℛAB.

Whereas allele counts are directly observed, haplotype phase is often ambiguous; therefore, PAB cannot be estimated as a proportion of AB haplotypes among all 2n haplotypes in a sample. The maximum-likelihood estimate  and, correspondingly,

and, correspondingly,  and

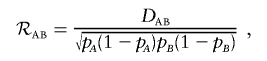

and  can be obtained. However, this approach usually requires the assumption of HWE—that is, the dilocus genotype frequencies are given by the products of frequencies of haplotypes. Weir and Cockerham22 suggested estimating the composite LD coefficient instead, defined as ΔAB=PAB+PA/B-2pApB, with the composite correlation

can be obtained. However, this approach usually requires the assumption of HWE—that is, the dilocus genotype frequencies are given by the products of frequencies of haplotypes. Weir and Cockerham22 suggested estimating the composite LD coefficient instead, defined as ΔAB=PAB+PA/B-2pApB, with the composite correlation

|

where DA and DB are the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium coefficients at two loci and PA/B is the joint frequency of alleles A and B at two different gametes. This coefficient is directly estimated from dilocus counts16 and, under HWE, corresponds to DAB. Weir20 and Schaid13 investigated statistical properties of the composite LD estimator and made comparisons of the composite ( ) and the maximum-likelihood (

) and the maximum-likelihood ( ) estimators. The composite estimator appears to perform well, since it is robust with respect to the HWE assumption.

) estimators. The composite estimator appears to perform well, since it is robust with respect to the HWE assumption.

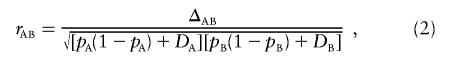

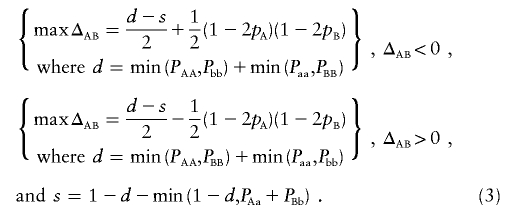

The maximum and minimum possible values for ΔAB, given genotypic frequencies at two loci, were reported by Hamilton and Cole15 and Zaykin.14 These values correspond to bounds on covariance between two trinary variables that take values −1, 0, and 1. Equation 4 in the work by Zaykin14 gives the bounds for abs(ΔAB) succinctly as

|

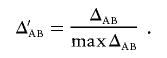

The standardized composite measure of LD with the range −1 to 1 is computed as

|

The standardization with use of equation (3) takes into account composite LD dependency on genotype frequencies and holds the promise for association-mapping applications. Cases and controls generally have different extents of gametic as well as nongametic disequilibria around a region of genetic association,10,14 which is captured by the composite LD.

Such a test is extended here to the comparison of whole matrices of standardized coefficients between the case and the control groups, to aid in identification of effects due to interactions among SNPs. The matrix of nonstandardized  coefficients is nonnegative definite, by virtue of being a variance-covariance matrix. Therefore, one can compute statistics on the basis of eigenvalue-eigenvector (spectral) decomposition of the LD matrix. Elsewhere, we proposed the use of spectral decomposition of the composite-LD matrix for selection of a subset of markers that optimize the information retained in a genomic region, using samples of population controls.23 The matrix of standardized composite LD is not necessarily positive definite, which limits the application of the spectral decomposition-based statistic. Another statistic used in this study is based on the overall LD difference (Z2).

coefficients is nonnegative definite, by virtue of being a variance-covariance matrix. Therefore, one can compute statistics on the basis of eigenvalue-eigenvector (spectral) decomposition of the LD matrix. Elsewhere, we proposed the use of spectral decomposition of the composite-LD matrix for selection of a subset of markers that optimize the information retained in a genomic region, using samples of population controls.23 The matrix of standardized composite LD is not necessarily positive definite, which limits the application of the spectral decomposition-based statistic. Another statistic used in this study is based on the overall LD difference (Z2).

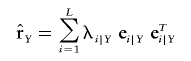

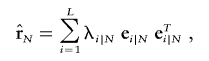

We define the standardized composite-LD matrices as Δ′Y and Δ′N and matrices of the composite LD correlation (eq. 2) for the case and the control groups as rY and rN. In both cases, diagonal entries of the matrices are equal to 1. Composite-LD matrices have spectral decompositions

|

and

|

where  are sample composite LD eigenvalues and eigenvectors (for the control, N, or for the case, Y, group), and T denotes the matrix transpose. Spectral decompositions based on the composite-LD covariance matrices ΔY and ΔN are defined similarly.

are sample composite LD eigenvalues and eigenvectors (for the control, N, or for the case, Y, group), and T denotes the matrix transpose. Spectral decompositions based on the composite-LD covariance matrices ΔY and ΔN are defined similarly.

We define matrices of first k column case and control eigenvectors by EY and EN, respectively. The two statistics are

and

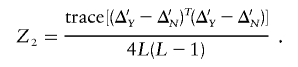

We suggest that the Z2 statistic should take a slightly different form when computed using the standardized LD:

|

In these equations, L is the number of markers and k⩽L is the number of principal components. The denominator, 4L(L-1), is the upper bound for the numerator of Z2. The denominator does not affect the magnitude of the resulting P value because it is invariant under permutations.

The statistic Z1 measures the difference between two spaces (sum of squared cosines of the angles between the eigenvectors) defined by the first k eigenvectors and ranges between k and 0 (maximum difference). Krzanowski described this statistic and the corresponding permutation-based tests (where the phenotype value is randomly shuffled among individuals) for comparison of two sets of principal components.24,25

The value k must be specified in advance. Krzanowski25 suggested using the value of k that is the largest integer smaller than L/2. This ensures that the “important” components are represented, whereas values k⩾L/2 will cause the subspaces defined by the two sets of eigenvectors to intersect in at least one dimension.

The sum-of-squared-differences statistic Z2 measures the overall difference in the corresponding pairwise LD. This statistic is also appropriate for comparing Δ′Y and Δ′N. Note that, for the standardized LD, the range of Z2 is 0⩽Z2⩽1, with 1 giving the maximum difference.

Both Z1 and Z2 definitions can be covariance based rather than correlation based. However, results for the covariance-based tests are not reported here because these tests showed consistently inferior power when compared with the correlation-based tests. We also performed a preliminary examination of several statistics based specifically on the comparison of corresponding LD eigenvectors as well as eigenvalues (e.g., sum of squared differences) between the case and the control groups. These tests did not show prominent power characteristics, and the results are not reported here. Nevertheless, detailed study of utility of such tests may warrant further investigation.

The generalized T2 test was applied in the association-mapping context by Xiong et al.26 This test employs the composite-LD matrix as part of the test statistic. The T2 test compares mean vectors of SNP values in cases and controls, where SNP values are obtained by recoding genotypes as AA→1, Aa→0, and aa→-1. The variance part of the T2 test statistic is the pooled variance-covariance matrix for the recoded values. It follows that, under the hypothesis of no association, the off-diagonal elements of this matrix are estimates of twice the composite LD coefficients, and the diagonal entries are twice the estimates of the variances of allele frequencies. Therefore, the generalized T2 test indirectly uses the composite LD in the variance part of the statistic.

Results

To evaluate performance of the proposed tests, we compared methods that are designed to detect either single-SNP effects or SNP interactions when the effects are associated with entire haplotypes. The T2 test is expected to have good power in the presence of several SNPs contributing to the association. In contrast, the min(P) test27 is most sensitive to a single associated SNP while accounting for correlation between SNPs due to LD. This test evaluates significance of the most extreme association test statistic (Armitage’s trend test in the present study). The significance is evaluated via permutations, preserving dependencies among SNPs. To detect haplotypic effects, we employed the “Haplotype Trend Regression” method of Zaykin et al.2 Methods used for power comparisons in this study are merely providing a reference point of comparison under different models. It is unlikely that a single “best” method can be recommended for the discovery of genetic associations, because the power obtained for the different methods will vary with the disease models assumed.

Pharmacogenetic Association-Mapping Example: CYP2D6

Identification of individual genetic differences in response to medicine has potential for reducing side effects and improving efficacy of drugs. The cytochrome p450 gene, CYP2D6, is involved in metabolism of ∼20% of marketed drugs.27 Hosking et al.28 described the association of SNP and haplotype polymorphisms with the poor drug-metabolizer phenotype in a region around the CYP2D6 gene. The data set consisted of 41 “poor metabolizer” cases and 977 controls. SNPs from the middle of the region show very high levels of association, which would be strongly supported by any of the tests discussed here. To illustrate an application of our technique, we identified six 5′-flanking consecutive SNPs. Missing genotypes were imputed with the package MICE.29 Further details of the data set are given in the work of Hosking et al.

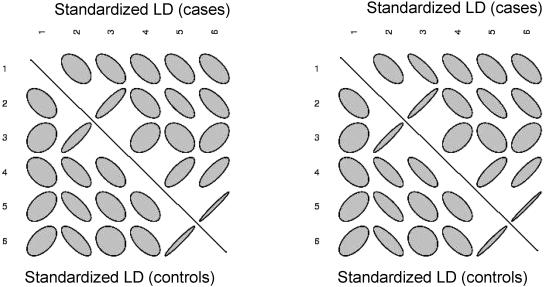

We found pronounced differences in LD between the case and the control groups. Figure 1 is a graphic presentation of the differences in LD and displays the LD matrices by use of ellipses whose shape reflects the magnitude of LD and whose direction reflects the sign of the disequilibrium: 45°-oriented ellipses reflect the positive sign of LD, whereas the more circular shape of an ellipse reflects a low degree of LD. Murdoch and Chow30 suggested the use of such graphs to display correlation matrices. Evidently, there are large observed differences, since some of the coefficients are reversed in sign. The values of r (left graph) and Δ′ (right graph) are similar to each other.

Figure 1.

LD ellipse plots for the CYP2D6 data. Left,  versus

versus  . Right,

. Right,  versus

versus  .

.

The difference in correlation is significant at the 5% level: for the Z2(r) test, P=.033, although the Z2(Δ′) test P value of .061 does not reach significance (all tests except the asymptotic T2 are based on 50,000 permutations). The test comparing the first two correlation-based principal components, Z1(k=2), gave a significant P value, .026. Statistics based on k=1,3 resulted in P values of .232 and .283, respectively. There is a multiple-testing issue involved with evaluating statistics that are based on the different numbers of principal components, k=1,2,3. Nevertheless, we note that the value k=2 corresponds to Krzanowski’s recommendation and could be set as the default value. The T2 test gave the P value equal to .337, reflecting the apparent absence of detectable effects associated with individual SNPs. Neither the allelic trend test nor the test comparing genotypic frequencies at individual SNPs was significant. The overall haplotypic test was not significant (P=.168). Thus, the application of the LD-contrast test to this particular data set shows that the method is successful in detecting the case-control LD difference, which supports visual differences in the LD patterns conveyed by figure 1.

Simulation I: 5-SNP and 6-SNP Haplotypes

A more extensive evaluation of the tests based on the Z1 and Z2 statistics was performed using simulations. When susceptibilities are driven mainly by haplotypes (i.e., there are pronounced haplotype effects but no interaction between haplotypes), it is expected that haplotypic tests should have optimal power. Nevertheless, there are notable exceptions to this rule. For two markers, Nielsen et al.10 showed that there are scenarios in which a test comparing LD coefficients is more powerful than is a single-locus or a haplotypic test. One situation in which this is the case is when multilocus susceptibilities induce an “orthogonal”-like distribution of dilocus haplotypes between the case and the control groups. By “orthogonal,” we mean the situation when high-susceptibility haplotypes tend to be defined by different SNPs. Culverhouse et al.31 considered epistatic models of this type.

To mimic this scenario, a set of simulations was constructed, under a haplotype-driven model common for all simulations. Haplotype frequencies were drawn from the Dirichlet(1,…,1) distribution. Effect sizes were drawn from the Gamma(1) distribution and were inspected to ensure that two large effect sizes (hi) are allocated to the most-distinct 6-SNP haplotypes—111111 and 222222—corresponding to a situation of two independent mutations in high LD with two very distinct haplotypes. To form an individual, a pair of haplotypes in these simulations was sampled from the population with the Dirichlet-derived haplotype frequencies. To obtain the binary outcome, the continuous phenotype values (Yijk=hi+hj+ek)—where ek∼N(0,σ2)—and σ=7.5 were dichotomized around two different threshold values, determined by the 0.05 and 0.5 population quantiles of Y. The population values of Δ′ among the cases and among the controls are listed in table 1. The correlation LD values followed the same pattern and were similar in values to the values of Δ′. The largest difference between the corresponding r and Δ′ coefficients was 0.06. The population LD values were small, which may correspond to a situation in which a set of SNPs in a candidate gene is selected on the basis of redundancy reduction.23 The largest case-control LD difference (0.116) was between the (1,4) and (4,1) entries of the LD matrix, the minimum difference was 0.009, and the mean difference was 0.07. For this set of simulations, 250 cases and 250 controls were sampled for each of 10,000 simulation runs.

Table 1.

Population Case-Control  Matrix for the 6-SNP Haplotype Heterogeneity Model (Simulation I)[Note]

Matrix for the 6-SNP Haplotype Heterogeneity Model (Simulation I)[Note]

| SNP1 | SNP2 | SNP3 | SNP4 | SNP5 | SNP6 | |

| SNP1 | .127 | .192 | .193 | .128 | −.181 | |

| SNP2 | .055 | .185 | .104 | .236 | −.048 | |

| SNP3 | .143 | .089 | .185 | −.138 | .268 | |

| SNP4 | .077 | .005 | .133 | .193 | .055 | |

| SNP5 | .042 | .187 | −.208 | .085 | -−.085 | |

| SNP6 | −.229 | −.108 | .160 | .045 | −.118 |

Note.— Above the diagonal of the matrix,  among the cases. Below the diagonal of the matrix,

among the cases. Below the diagonal of the matrix,  among the controls.

among the controls.

Tests based on Z1 and Z2 statistics (with use of both Δ′- and r-based versions of Z2) were performed, and P values were recorded. Results of these simulations for the two values of population prevalence are shown in table 2. The results show that the LD-contrast test that is based on the squared difference statistic (Z2) has the largest power with use of both the Δ′ and the correlation-based definitions.

Table 2.

Power Values for the 6-SNP Haplotype Heterogeneity Model (Simulation I) [Note]

| Prevalence | Haplotype Test | T2 | Z1 (k=1) | Z1 (k=2) | Z2 (Correlation) | Z2 (Δ′) | min(P) |

| .05 | .388 | .081 | .365 | .417 | .663 | .654 | .073 |

| .50 | .251 | .081 | .196 | .301 | .454 | .443 | .073 |

Note.— k=1 for the Z1 test corresponds to ∼15% of variation accounted by principal components. k=2 for the Z1 test corresponds to ∼25% of variation accounted by principal components. min(P) = single-SNP permutation-based trend (allelic) test.

The power of the haplotype-based test2 was substantially lower, and the power of both T2 and min(P) (single-SNP permutation-based trend allelic test) was low. The power of the principal components-based test (Z1) was lower then the power of the test based on the Z2 statistic. However, in this model, it was higher than the power of the T2, min(P), and the haplotypic tests (at the value of k<L/2=2). Dichotomization around the population mean to produce the binary outcome yielded results similar to the quantile-defined thresholds just described (data not shown). In addition to these results with fixed parameters, we conducted a set of 5-SNP simulations in which samples of haplotypes were obtained using the forward evolutionary model of drift with recombination.32 The simulations are “forward” to distinguish them from a popular coalescent approximation of this process, which operates “backwards” in time. These forward simulations are a typical implementation of a genetic drift with admixture population-genetic model and with nonoverlapping generations and recombination modeled as a Poisson process. A very similar model was used by Zaykin et al.2 The effects that determine susceptibilities were sampled from a template that induces pairwise orthogonality, with added normal variability. In contrast to the simulation just described, all population parameters were sampled anew prior to each simulation. This allowed averaging across a variety of models. The power is not necessarily expected to be reduced in this setup. In general, larger variance associated with haplotype effects would result in higher power values of the tests. In addition, the induced “marginal effects” at the level of SNPs and dilocus haplotypes are dependent on both the susceptibility values and the population frequencies.

In these simulations, we observed that the 5×5 composite-LD matrix comparison tests (Z2) still had higher power on average (88% power for the correlation and 75% for Δ′) than either the generalized T2 (55% power) or the haplotype-specific test (60% power). Thus, these simulations confirmed that the power of the LD-contrast tests is still the highest, as was found to be the case for the fixed set of effects and frequencies.

Simulation II: 15- and 30-SNP Haplotypes

An evaluation of the tests in which the trait variation is determined by the diploid pairs of haplotypes (diplotypes) was performed using simulations. For this model, we used much larger—15-SNP and 30-SNP—haplotypes sampled from a population generated by the forward evolutionary model of drift with recombination.32 The phenotype model was similar to the one described above. We considered a more general, diplotype-driven model, in which normally distributed diplotype, rather than haplotype, effects were added to the trait value, together with the common normal error. New diplotype effects were sampled prior to each simulation. In this set of simulations, the trait values have been dichotomized around the mean to produce a binary trait. The LD-contrast tests were verified to have the correct type I error by setting the population genetic effects to zero and examining quantiles of the resulting P value distribution.

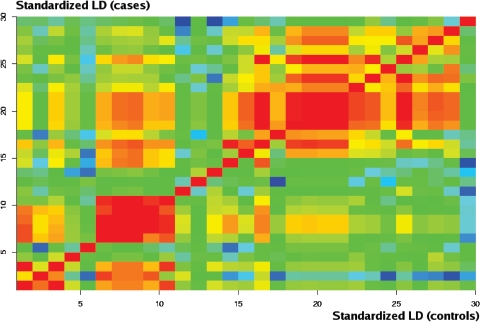

This set of simulations generated relatively high pairwise LD. The two middle quartiles for the population LD distribution (measured by rAB) were estimated to be 0.413 and 0.975, with the median value of 0.735. One of the 30-SNP samples from this simulation study was used to produce an illustrative graphic plot of pairwise LD (fig. 2). The plot illustrates LD differences between the upper (cases) and the lower (controls) samples. For example, there is a region of high LD around the marker pair (21,8) in the cases, whereas this region has relatively low LD in the controls. Nonetheless, statistical tests, as described here, are needed to assess the extent to which these LD differences can be attributed to the sampling variation.

Figure 2.

Composite LD color plot (sample data set from Simulation II with 29 SNPs). Above the diagonal,  . Below the diagonal,

. Below the diagonal,  . Δ′-based LD difference P<1×10-3. The scale of colors from blue (lower values) to red (higher values) corresponds to the increase in abs(Δ′).

. Δ′-based LD difference P<1×10-3. The scale of colors from blue (lower values) to red (higher values) corresponds to the increase in abs(Δ′).

As before, we assumed haplotypic phase to be unknown. Many published haplotype association–mapping algorithms would not be computationally feasible, given the large number of SNPs. The generalized T2 test26 was used for the comparison, as was the single SNP–based “min(P)” shuffling test, in which the significance of the allelic trend test with the maximum value of χ2 is obtained via permutations.33,34

It should be noted that the T2 test has high power when alleles of multiple SNPs independently contribute to the trait, because the test compares means of SNP scores between the case and the control groups. In both 15-SNP and 30-SNP settings, we observed similar power for the T2 and Z2 tests.

For the 15-SNP data, the power was 0.71 for T2 and Z2, when Z2 was based on the correlation LD matrix (table 3). The power for the Z2 test based on the standardized matrix was lower, 0.62. The power of the single-SNP permutation-based trend (allelic) test was 0.57. Thus, despite taking into account the correlation between SNPs, single-marker tests had relatively lower power. We computed the eigenvector statistic Z1 for values of k required to account for various proportions of the variance (0.5,0.75,0.9), as can be determined by the cumulative sum of eigenvalues (such an approach has been employed elsewhere by Meng et al.23). The maximum value of k was set to 7. This resulted in k equal to 1–3 ( ) for 0.5 of the variance, k equal to 1–6 (

) for 0.5 of the variance, k equal to 1–6 ( ) for 0.75 of the variance, and k equal to 6–7 (

) for 0.75 of the variance, and k equal to 6–7 ( ) for 0.9 of the variance. Fixed values of k have been tried as well; however, we could not achieve power comparable to that of the test based on Z2. Because of higher LD in this set of simulations, the best power was observed at intermediate values of k.

) for 0.9 of the variance. Fixed values of k have been tried as well; however, we could not achieve power comparable to that of the test based on Z2. Because of higher LD in this set of simulations, the best power was observed at intermediate values of k.

Table 3.

Power Values for the Diplotype-Driven Model with 15 and 30 SNPs (Simulation II)

| SNPs | T2 | Z1 (50% Variation) | Z1 (75% Variation) | Z1 (90% Variation) | Z2 (Correlation) | Z2 (Δ′) | min(P)a |

| 15 | .707 | .478 | .423 | .407 | .711 | .617 | .569 |

| 30 | .818 | .563 | .621 | .488 | .847 | .773 | .171 |

min(P) = single-SNP permutation-based trend (allelic) test.

Similar relative power was observed for the 30-SNP data. When Z2 was based on the correlation LD matrix, the power was 0.82 for the T2 test, 0.85 for the Z2 test, and 0.77 for the Z2 test based on the standardized LD (Δ′). The eigenvector statistic–based test (Z1) had highest power, 0.62, at the proportion of the variance equal to 0.75, which corresponded to k=2–8 ( ). The single-SNP permutation-based trend test had very low power, 0.17.

). The single-SNP permutation-based trend test had very low power, 0.17.

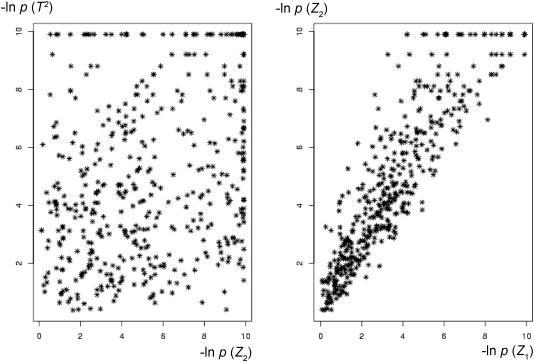

Although the LD-matrix comparison test was found to have power similar to the generalized T2, our results suggest that these tests tend to identify essentially different attributes of genetic association in a region. The left graph of figure 3 shows a plot of P values obtained from the T2 test versus the corresponding P values of Z2 (15-SNP simulation). The correlation between the two tests was quite low (0.36), and over half of T2 test P values >.05 were <.05 when evaluated with Z2. On the other hand, the right graph for the correspondence between Z1 and Z2 statistics shows very large correlation (0.91). The Z1 test for the difference between the case group and the control group principal components had lower power than the test based on Z2, which shifted points up from the diagonal on the second graph.

Figure 3.

Correspondence between P values (Simulation II with 15 SNPs). Left, Plot of T2 versus Z2 −log of P values (low correlation). Right, Plot of Z1 versus Z2 −log of P values (high correlation).

Discussion

Genetic association studies typically report characterization of LD in candidate regions with LD plots—that is, using graphic representation of LD matrices.9 These plots are usually given for population control samples, although LD plots for case samples are reported and are compared (visually) with the LD pattern in control samples. Rubio et al.35 compared graphic plots of LD between multiple sclerosis case and control samples in the human leukocyte antigen region and concluded that D′ values appeared slightly higher in the case sample. Suarez et al.36 compared specifically composite LD coefficients between samples of alcoholics and nonalcoholics and concluded that there was similarity in the pattern of LD, “although there is the suggestion of less disequilibria in the alcoholic sample than among the controls” (p. 14). We suggest that such comparisons be complemented by a statistical procedure. Moreover, we found that the power of comparing LD patterns is comparable to that of traditional mapping techniques, or is even superior in certain situations.

The standardized LD coefficient D′ remains a popular measure that accounts for dependence of the LD range on allele frequencies. However, one of the problems with an EM-based estimator is the requirement of the random union of haplotypes (haplotypic HWE). We resolve this problem by accommodating results of Hamilton and Cole15 and Zaykin,14 and we suggest that the plots can be based on the standardized composite coefficient. Straightforward definitions of the composite and standardized composite LD, as well as the efficiency of the computations, make it easy to compare LD plots between samples of cases and controls. Such comparisons can be done “by eye,” but a statistical procedure is desirable. An asymptotic test to compare two LD (i.e., covariance) matrices can be constructed; however, such tests are rather sensitive to distributional assumptions.37,38 In addition, the distribution theory and inference become much more complicated once normalizations of covariance (e.g., correlation) are considered.25 Because of these concerns, we adopted the permutational framework to provide comparison of LD matrices based on the composite coefficient and its standardized version.

Statistical approaches specifically tailored for identification of haplotype effects are being rapidly developed.39 There is strong biological evidence that entire haplotypes rather than single SNPs are important in determining the trait variation. Therefore, identification and estimation of haplotype effects are important issues. Still, the multiplicity of haplotypes and phase uncertainty adversely affect statistical power. Multilocus “scoring” approaches that capitalize on marginal effects of individual SNPs are being developed as well. These approaches indirectly take into account the interaction between SNPs while adjusting for LD.26,40

In particular, these approaches are expected to have good power under models that induce substantial marginal SNP effects and strong LD. Although haplotype-based approaches and scoring methods, such as the generalized T2 test, provide relatively high power in the respective situations, it has been noted that the extent of LD can be markedly different between the case and the control groups in a region of genetic association.8 Therefore, a case-control LD comparison appears to be a promising addition to existing methods of characterizing multilocus associations. Further, Nielsen et al.10 examined a two-SNP situation and found that a test comparing LD coefficients can be more powerful than a single-locus or a haplotypic test.

We extend these results to the case of multiple SNPs. The LD-contrast test, like any other method, would not be expected to have superior power across all susceptibility models. One virtue of the LD-contrast test is the reduced number of parameters (e.g., there is only a single LD coefficient in the two-SNP case, although there are four haplotypes), and, as we discuss here, there are certain models that may result in good power of the LD-contrast test. A prominent example is when multilocus susceptibilities induce orthogonal-like distribution of dilocus haplotypes in cases and controls. Heterogeneity models in which mutations are associated with haplotypes that are distinct, with respect to a large proportion of the alleles that they carry, may result in such orthogonality for some of the dilocus pairs. To illustrate why the LD contrast test can work well under these scenarios, denote two alleles at either of two loci by 1 and 2: A≡1, B≡1, a≡2, b≡2c. The disequilibrium coefficient can be written in terms of the haplotype frequencies as DAB≡D11=P11P22-P12P21. The disequilibrium is large in a particular sample if the haplotypes 11 and 22 are overrepresented compared with the two other types. Therefore, the ratio DcasesAB/DcontrolsAB tends to deviate from 1 when the orthogonal haplotypes 11 and 22 are overrepresented in one of the groups. A similar situation holds with the composite LD definition, because the value of the sum DAB+DA/B increases with DAB. Moreover, we found that, whereas the T2 test and the LD contrast test provide similar power under a general diplotype-driven model, the correlation between P values of the two tests is low (left graph of fig. 3), which suggests that these approaches distinguish between different aspects of association. That is, the LD comparison tests are more sensitive to interactions that tend to induce small marginal effects associated with individual SNPs. The magnitude of marginal effects is largely unpredictable in practice, since it is determined by both multilocus susceptibility values and the corresponding population frequencies. Therefore, it would vary from population to population, given the same penetrance configuration.

The question remains: which measure, Δ′ or the correlation r, is more appropriate for the comparison of patterns of LD? Two samples can have equal LD correlation values even when the standardized LD coefficients are unequal, and vice versa,41 making the a priori choice of the statistic somewhat difficult. An appealing feature of the standardization by the LD bounds (“di-prime-ization”) in that it makes the measure independent of single locus frequencies. The independence is in the sense of the range that the coefficient can take. The allele frequencies very much remain a part of that definition,42,43 and it would be a mistake to interpret the standardized coefficient as being free of dependencies on the allele or genotype frequencies. On the other hand, the correlation coefficient enjoys well-defined statistical and population-genetic properties and gives a straightforward extension to the principal components–based inference. The simulations (Simulation II) show somewhat higher power of the tests based on the correlation, and the CYP2D6 data set considered here provides an example in which the test based on the correlation provides slightly stronger evidence of association (P=.033 vs. P=.061), although both results can be considered indicative of association. In the absence of a specific hypothesis, it seems reasonable to employ the correlation-based analysis and to reserve the Δ′-based LD comparisons for more-detailed characterizations of LD. Nevertheless, the correlation and the Δ′-based comparisons address different hypotheses, and both tests have their value. Our choice of a particular simulation design might have favored greater deviations from the equality of correlations. The orthogonal model (Simulation I), in which the correlation and the Δ′ values were almost identical, showed similar power of the two tests.

In our simulations, we found that the squared difference–based statistic has better power than the statistic based on the comparison of the principal components, although the correlation between P values obtained for these tests is high. The squared difference is more of an omnibus test. For example, if the amount of LD is proportionally higher among the cases for all pairs of markers, the principal-components test will lack power. In addition, there is uncertainty about the number of components to use. Still, such tests can provide a description of the multivariate structure of LD. The principal component–based analysis seems to be most valuable at the descriptive stage once the association is established. The default value for the number of principal components (k) can be set to Krzanowski’s recommendation25 to use the largest integer k that is smaller than L/2.

In summary, we suggest that statistical approaches to compare pairwise LD matrices between the case and the control samples are useful additions to already-available statistical-mapping tools. As with single-marker case-control analysis, population heterogeneity is an issue. Further research should emphasize extending these methods to accommodate family data and to provide methods robust to population stratification and admixture.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Programs implementing the LD-contrast tests are available at D.V.Z.'s Web site and from D.V.Z. on request. Liling Warren, Norman Kaplan, and two reviewers provided useful comments that improved the manuscript.

Web Resource

The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

- D.V.Z.'s Web site, http://statgen.ncsu.edu/zaykin/Dprime/

References

- 1.Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA (2002) Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am J Hum Genet 70:425–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaykin DV, Westfall PH, Young SS, Karnoub MA, Wagner MJ, Ehm MG (2002) Testing association of statistically inferred haplotypes with discrete and continuous traits in samples of unrelated individuals. Hum Hered 53:79–91 10.1159/000057986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stram DO, Leigh Pearce C, Bretsky P, Freedman M, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Thomas DC (2003) Modeling and E-M estimation of haplotype-specific relative risks from genotype data for a case-control study of unrelated individuals. Hum Hered 55:179–190 10.1159/000073202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein MP, Satten GA (2003) Inference on haplotype effects in case-control studies using unphased genotype data. Am J Hum Genet 73:1316–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin DY (2004) Haplotype-based association analysis in cohort studies of unrelated individuals. Genet Epidemiol 26:255–264 10.1002/gepi.10317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata K, Ito T, Kitamura Y, Iwasaki N, Tanaka H, Kamatani N (2004) Simultaneous estimation of haplotype frequencies and quantitative trait parameters: applications to the test of association between phenotype and diplotype configuration. Genetics 168:525–539 10.1534/genetics.104.029751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris AP (2005) Direct analysis of unphased SNP genotype data in population-based association studies via Bayesian partition modelling of haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol 29:91–107 10.1002/gepi.20080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes MG, Roe CA, Ng M, Bosque-Plata L, Tsuchiya T, Wu X, Ambrose NG, Yairi E, Cook EH, Cox NJ (2004) Case-control differences in linkage disequilibrium as a tool for gene mapping in complex diseases. Am J Hum Genet Suppl 54:A146 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abecasis GR, Cookson WO (2000) GOLD—graphical overview of linkage disequilibrium. Bioinformatics 16:182–183 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen DM, Ehm MG, Zaykin DV, Weir BS (2004) Effect of two- and three-locus linkage disequilibrium on the power to detect marker/phenotype associations. Genetics 168:1029–1040 10.1534/genetics.103.022335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen DM, Ehm MG, Weir BS (1998) Detecting marker-disease association by testing for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium at a marker locus. Am J Hum Genet 63:1531–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittke-Thompson JK, Pluzhnikov A, Cox NJ (2005) Rational inferences about departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet 76:967–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaid DJ (2004) Linkage disequilibrium testing when linkage phase is unknown. Genetics 166:505–512 10.1534/genetics.166.1.505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaykin DV (2004) Bounds and normalization of the composite linkage disequilibrium coefficient. Genet Epidemiol 27:252–257 10.1002/gepi.20015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton DC, Cole DE (2004) Standardizing a composite measure of linkage disequilibrium. Ann Hum Genet 68:234–239 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir BS (1996) Genetic data analysis II. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huttley GA, Wilson SR (2000) Testing for concordant equilibria between population samples. Genetics 156:2127–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewontin RC (1964) The interaction of selection and linkage. I. General considerations; heterotic models. Genetics 49:49–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yule GU (1912) On the methods of measuring association between two attributes. J R Stat Soc 75:579–642 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weir BS (1979) Inferences about linkage disequilibrium. Biometrics 35:235–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peduzzi PN, Detre KM, Chan YK (1983) Upper and lower bounds for correlations in 2×2 tables—revisited. J Chronic Dis 36:491–496 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1979) Estimation of linkage disequilibrium in randomly mating populations. Heredity 42:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng Z, Zaykin DV, Xu C-F, Wagner M, Ehm MG (2003) Selection of genetic markers for association analyses, using linkage disequilibrium and haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet 73:115–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krzanowski WJ (1979) Between-groups comparison of principal components. J Am Stat Soc 74:703–707 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krzanowski WJ (1993) Permutational tests for correlation matrices. Stat Comput 3:37–44 10.1007/BF00146952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong M, Zhao J, Boerwinkle E (2002) Generalized T2 test for genome association studies. Am J Hum Genet 70:1257–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans WE, Relling MV (1999) Pharmacogenomics: translating functional genomics into rational therapeutics. Science 286:487–491 10.1126/science.286.5439.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosking LK, Boyd PR, Xu CF, Nissum M, Cantone K, Purvis IJ, Khakhar R, Barnes MR, Liberwirth U, Hagen-Mann K, Ehm MG, Riley JH (2002) Linkage disequilibrium mapping identifies a 390 kb region associated with CYP2D6 poor drug metabolising activity. Pharmacogenomics J 2:165–175 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Buuren S, Oudshoorn CGM (2000) Multivariate imputation by chained equations: MICE V1.0 user’s manual. TNO Prevention and Health Report PG/VGZ/00.038, Leiden, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murdoch DJ, Chow ED (1996) A graphical display of large correlation matrices. Am Statistician 50:178–180 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Culverhouse R, Klein T, Shannon W (2004) Detecting epistatic interactions contributing to quantitative traits. Genet Epidemiol 27:141–152 10.1002/gepi.20006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almasy L, Terwilliger JD, Nielsen D, Dyer TD, Zaykin D, Blangero J (2001) GAW12: simulated genome scan, sequence, and family data for a common disease. Genet Epidemiol Suppl 21:332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Churchill GA, Doerge RW (1994) Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics 138:963–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westfall PH, Zaykin DV, Young SS (2002) Multiple tests for genetic effects in association studies. Methods Mol Biol 184:143–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio JP, Bahlo M, Butzkueven H, van Der Mei IA, Sale MM, Dickinson JL, Groom P, Johnson LJ, Simmons RD, Tait B, Varney M, Taylor B, Dwyer T, Williamson R, Gough NM, Kilpatrick TJ, Speed TP, Foote SJ (2002) Genetic dissection of the human leukocyte antigen region by use of haplotypes of Tasmanians with multiple sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet 70:1125–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suarez BK, Parsian A, Hampe CL, Todd RD, Reich T, Cloninger CR (1994) Linkage disequilibria at the D2 dopamine receptor locus (DRD2) in alcoholics and controls. Genomics 9:12–20 10.1006/geno.1994.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Box GEP (1953) Non-normality and tests on variances. Biometrika 40:318–335 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boos DD, Brownie C (2004) Comparing variances and other measures of dispersion. Statistical Science 19:571–578 10.1214/088342304000000503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaid DJ (2004) Evaluating associations of haplotypes with traits. Genet Epidemiol 27:348–364 10.1002/gepi.20037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clayton D, Chapman J, Cooper J (2004) Use of unphased multilocus genotype data in indirect association studies. Genet Epidemiol 27:415–428 10.1002/gepi.20032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zapata C, Alvarez G (1997) Testing for homogeneity of gametic disequilibrium among populations. Evolution 51:606–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedrick PH (1987) Gametic disequilibrium measures: proceed with caution. Genetics 117:331–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewontin RC (1988) On measures of gametic disequilibrium. Genetics 120:849–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]