Abstract

Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factors, NHERF1 and NHERF2, are structurally related proteins and highly expressed in epithelial cells. These proteins are initially identified as accessory proteins in the regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3, NHE3. In addition to regulation of NHE3, recent studies demonstrate the importance of NHERF1 and NHERF2 in recycling and localization of membrane receptors, ion channels and transporters. Recent studies show that serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 (SGK1) specifically interacts with NHERF2 but not with NHERF1, adding to the growing number of differences between the two proteins. The association of SGK1 with NHERF2 is necessary for stimulation of NHE3 activity by glucocorticoids. In addition, SGK1 together with NHERF2 stimulates the K+ channel ROMK1, suggesting a broader role of SGK1 in regulation of ion transport.

Keywords: Na+/H+ exchanger, NHERF, SGK1, Glucocorticoids

Introduction

The formation of protein complexes is the basis for efficient propagation in many cellular signaling processes. In this regard, the PDZ domain has emerged as a major mediator of protein sequestration in the plasma membrane. Studies show that Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factors (NHERFs) play significant roles in assembly of protein complexes at the apical membrane of epithelial cells. This review focuses on the recent finding that SGK1 in conjunction with NHERF2 is involved in stimulation of NHE3 and other ion transport processes.

Role of SGK1 in Na+ transport

Serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase (SGK) is a serine/threonine kinase, which was originally identified through subtractive cloning of a serum and glucocorticoid-induced mammary tumor cell cDNA library [1]. SGK is an ancient kinase, with homologues present in organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Saccharomyces cerevesiae [2–4]. In mammalian tissues and cells, three isoforms of SGK have been identified: SGK1, SGK2 and SGK3/CISK [1, 5, 6]. SGK1 and SGK3 are ubiquitously expressed whereas SGK2 exhibits more restricted tissue distribution [1, 5]. SGK1 is induced by various stimuli such as serum, glucocorticoids, follicle-stimulating hormone, aldosterone, cell shrinkage, PKA, expression of p53 and injury to the brain [7]. In contrast, SGK2 and SGK3 genes are not induced by serum or glucocorticoids [5]. Although the physiological role of SGK1 in general is not yet clear, studies demonstrate the importance of SGK1 in epithelial ion transport. Significant amount of data support the role of SGK1 in regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in conjunction with the ubiquitin-protein ligase neural precursor cell-expressed, developmentally downregulated isoform Nedd4-2 [8–11]. My laboratory recently observed that SGK1 plays an essential role in regulation of NHE3 by glucocorticoids [12].

NHE3

Mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) represent a growing family of membrane transporters that drive H+ flux in exchange for external Na+ in an electroneutral manner. To date, at least seven NHE isoforms have been cloned and partially characterized [13–15]. All the Na+/H+ exchangers share similar structure with the N-terminal transmembrane domain and the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain. The membrane domain of approximately 450 amino acids performs the ion transport function, whereas cellular signals converge onto the cytoplasmic domain. The C-terminal domain exhibits the largest divergence among the Na+/H+ exchangers and contains several potential phosphoryation sites and motifs for protein-protein interactions [14, 16, 17]. Works from various laboratories suggest that the interaction between the membrane and cytoplasmic domains is needed in regulation of Na+/H+ exchangers [18, 19]. The different Na+/H+ exchangers have distinct pharmacological and physiological characteristics and differ in tissue distribution. Of these, NHE1 is ubiquitously expressed and attributed to the maintenance of intracellular pH. Although functions and expression of other NHE isoforms vary among different tissues and animals, it is widely accepted that NHE3 is the apical Na+/H+ exchanger in the small intestine, proximal colon and renal proximal tubules [20, 21]. Through osmotic coupling to passive water absorption, NHE3 is a major constituent in basal Na+ absorption in intestine and a frequent target of inhibition in many diarrheal diseases [22, 23]. In kidney, as much as 70% of the total HCO3− reabsorption can be attributed to NHE3 [21, 24, 25]. Although no specific disease has been associated to specific defects in NHE3 protein or gene, deficiency in NHE3 expression in mouse results in severe intestinal and renal defects associated with significant perturbation in Na+ and HCO3− reabsorption [20, 21, 25, 26].

Na+/H+ exchangers display remarkable functional versatility. In addition to exhibiting sensitivity to intracellular pH, they are modulated by changes in cell volume, cellular ATP concentration, growth factors and hormones [13, 24, 27]. Despite of large efforts made in recent years in understanding regulation of NHEs, molecular mechanisms underlying Na+/H+ exchanger regulation are not fully understood. Regulations of Na+/H+ exchangers are complex involving phosphorylation-dependent and independent mechanisms, cytoskeletal interaction, and membrane recycling between the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic pools [28–31]. For more details readers should refer to recent reviews on the mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers [14, 16].

PDZ domain

The PDZ domain was identified as a homologous element present in PSD-95, the Drosophila disc-large tumor suppressor protein DlgA and the tight-junction protein ZO-1. The PDZ domain initially referred to as the Dlg homology region (DHR) or the GLGF repeat, based on the presence of a Gly-Leu-Gly-Phe sequence motif [32]. The PDZ domain is made up of 80–90 amino acid residues that preferentially bind short peptide sequences located at the C-terminus of the interacting proteins [33, 34]. High-resolution structure studies of PSD-95, hDlgA, nNOS, phosphatase hPTP1E and NHERF1 show that PDZ domains consist of six β-sheets and two α-helices forming a hydrophobic pocket to accommodate a C-terminal carboxylate group. [35–38]. Mutational analysis demonstrates that PDZ domains have distinct peptide binding specificity with the consensus sequence -(T/S)-x-V/L [34, 39–41]. In addition to the prototypical C-terminal binding, PDZ domains are also observed to form dimers or interact with internal sequences that mimick a free C-terminus by forming β hairpin ”finger” [37, 42, 43]. In one case, the interaction involves non-C terminal cyclic peptides [44].

NHE3 associated regulatory proteins, NHERF1 and NHERF2

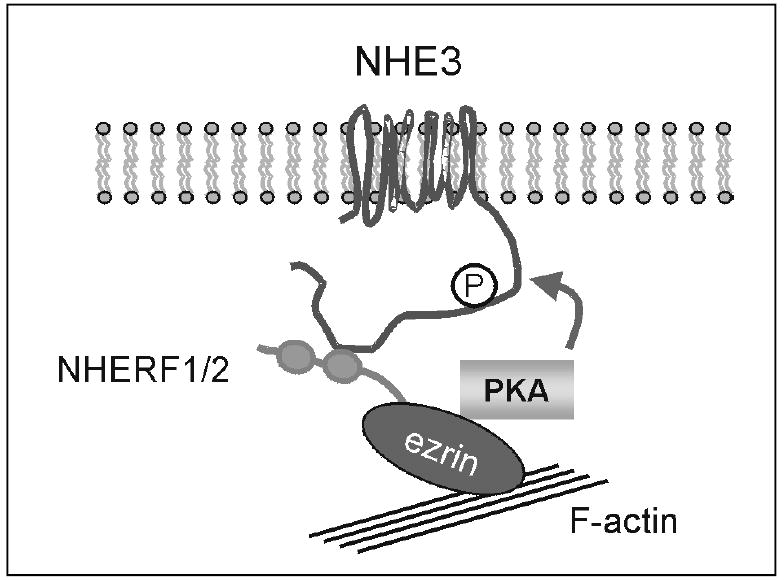

NHE regulatory factor 1, NHERF1, was cloned as a protein that can reconstitute protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent inhibition of NHE3 in renal brush border vesicles [45, 46]. Using the cytoplasmic domain of NHE3 as bait in a yeast two-hybrid system, Yun et al. [47] cloned E3KARP (NHE3 kinase A regulatory Protein), which was later renamed NHERF2 to be consistent with the nomenclature of the family. NHERF2 shares 62% similarity with NHERF1 and both proteins contain two tandem PDZ domains. It was shown that NHERF1 and NHERF2 reconstitute PKA-dependent inhibition of NHE3 in a cell line lacking these accessory proteins [47]. To determine the functional roles of NHERF2 in regulation of NHE3 by PKA, we considered two possibilities. An earlier work implicated PKA-dependent phosphorylation of NHERF [48], and the general function of proteins with PDZ domains as scaffold proteins raised the possibility of the direct scaffolding of PKA by NHERFs acting as A kinase anchoring proteins (AKAP) that specifically binds the regulatory subunit of type II PKA. However, neither mode was proven significant in regulation of NHE3 [49]. Using a pull-down assay, the human homologue of NHERF1, EBP50 (Ezrin Binding Protein 50), was identified as a protein that binds the cytoskeletal protein ezrin with high affinity [50]. It is subsequently demonstrated that NHERF1 and 2 interact with ezrin through the C-terminal 29 amino acids [51, 52]. The essence of this interaction is that ezrin functions as an AKAP [49, 53]. This linkage to ezrin via NHERFs allows compartmentalization of PKA to the vicinity of NHE3 enabling phosphorylation of NHE3 [49, 50, 54] (Figure 1). Through the interaction with ezrin, NHERFs link NHE3 to the actin cytoskeletal network. Although not proven unequivocally, the sensitivity of NHE3 to the actin disrupting agents may results from the association of NHE3 with actin filaments by NHERFs/ezrin [55].

Fig. 1.

Proposed organization of proteins involved in the PKA-dependent regulation of NHE3.

Diverse functions of NHERFs

Although NHERF was identified as a protein potentially regulating NHE3, Northern analysis of NHERF1 and NHERF2 on human tissues shows broad expression patterns of both isoforms, suggesting that functions of NHERFs are not limited to regulation of NHE3 [47]. This assumption is supported by identification of proteins other than NHE3 interacting with NHERFs. These include the G protein-coupled receptors, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor, the intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger encoded by the down regulated in adnoma (DRA) gene, phospholipase Cβ, mammalian Ca2+ channel Trp4, transcriptional factors and the ezrinradixin-moesin (ERM) family proteins [41, 50, 56–64]. Because of the their roles in many signaling pathways converging onto membrane proteins, NHERFs represent a prototypical example of a scaffold protein organizing multi-signaling elements on the plasma membrane. Due to the similarities between NHERF1 and NHERF2 in structure and amino acid sequences, it is generally assumed that both proteins interact with the same target proteins, and hence the functions of NHERF1 and 2 are often thought to be redundant. However, increasing data demonstrate that NHERF1 and NHERF2 interact with different sets of proteins [12, 61–68].

The functions of NHERFs are diverse but a few aspects are worthy discussing in this review. One function of NHERFs is to mediate clustering of signaling proteins in micro-domains to facilitate cellular signaling processes. The importance of protein compartmentalization is amply demonstrated in PKA-dependent inhibition of NHE3 in which NHERFs bring PKA in the proximity of NHE3 by acting as a functional AKAP. Hall et al. elegantly demonstrated that the compartmentalization can alter the outcome of a cellular signal by showing that an activation of the β2-adrenergic receptor sequesters NHERF1 to the C-terminal end of the receptor rendering it unavailable for interaction with NHE3 and hence NHE3 is not regulated despite an elevation in cAMP level [56]. Similarly, the interaction of NHERF2 with the parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor has been shown to direct the signaling of the PTH receptor between adenylate cyclase and phospholipace Cβ [60].

The second major function of NHERFs that is becoming increasingly evident is regulation of endocytosis and endocytic recycling. Deletion of the C-terminal PDZ interacting motif of the β2-adrenergic receptor specifically prevents recycling of the β2-adrenergic receptor without affecting other endocytic pathways [69]. Similarly, The C-terminal deletion of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), disabling its interaction with PDZ domains, drastically reduces the apical membrane retention of CFTR by altering its endocytosis [70]. On the other hand, NHERF interaction of the κ opioid receptor promotes entry into the endocytic pathways [71].

In other cases, proper apical targeting of membrane proteins has been related to the PDZ binding of NHERFs. The polarized distribution of CFTR requires the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif although additional motifs are also required for the proper apical targeting [72, 73]. The type IIa Na/Pi-cotransporter (NaPi4) present in the apical membrane of renal proximal tubules interacts with the first PDZ domain of NHERF1 [74]. Overexpression of the first PDZ domain of NHERF1 is thought to disrupt its interaction with the cytoskeleton and decreases the apical expression of NaPi4 [75]. In fact, genetic deletion of NHERF1 results in internalization of NaPi4 and decreased apical targeting NaPi4 in the renal proximal tubules [76]. Takeda et al. demonstrated that coupling of podocalyxin to the actin cytoskeleton via NHERF2 is essential in maintenance of foot-processes in glomerular epithelial cells [77]. It is subsequently shown that the interaction with NHERF2 is necessary for the apical membrane targeting of podocalyxin in MDCK cells [78].

Regulation of NHE3 by glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids have been used effectively to achieve rapid symptomatic relief in many clinical situations including inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [79]. Despite their wide use, the exact mechanism of action of glucocorticoids remains elusive. The anti-inflammatory effect of corticosteroids arises from the direct and indirect inhibition on cytokines and inflammatory mediators [79]. In addition, it is widely accepted that glucocorticoids have direct effect on intestinal salt and water absorption, and thus alleviate diarrhea [80–82]. Pharmacologic doses of methylprednisolone have been shown to increase Na+, Cl− and water absorption in vivo in both small intestine and colon of rat. It has been shown that 1 to 3 day treatment with methylprednisolone doubled rabbit ileal neutral NaCl absorption by specifically stimulating NHE3 mRNA expression 4–6 fold without affecting NHE1 [83, 84]. Cho et al. found dexamethasone had a stimulatory effect on NHE3 gene expression in rat ileum and proximal colon, but not in jejunum or distal colon [84]. Glucocorticoid excess also increases net acid secretion and HCO3− absorption in the kidney by activation of NHE3 gene expression [85–88]. Genomic cloning of rat NHE3 reveals the presence of glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) in the 5’-flanking promoter region and the glucocorticoid responsiveness of Nhe3 gene was demonstrated by in vitro transcription assays [89, 90].

Although many of these earlier work suggested genomic stimulation of Na+/H+ exchange by glucocorticoids, acute effects of glucocorticoids on Na+/H+ exchange independent of change in NHE3 mRNA abundance were also observed. Incubation of proximal tubules for 3 hr with dexamethasone resulted in significant increase in NHE3 activity without change in NHE3 mRNA abundance [86]. Consistently, incubation of human colonic carcinoma cell line Caco-2 with dexamethasone for 4 hr led to increased NHE3 transport in the absence of increased NHE3 transcription [12].

Stimulation of NHE3 by SGK1 and NHERF2

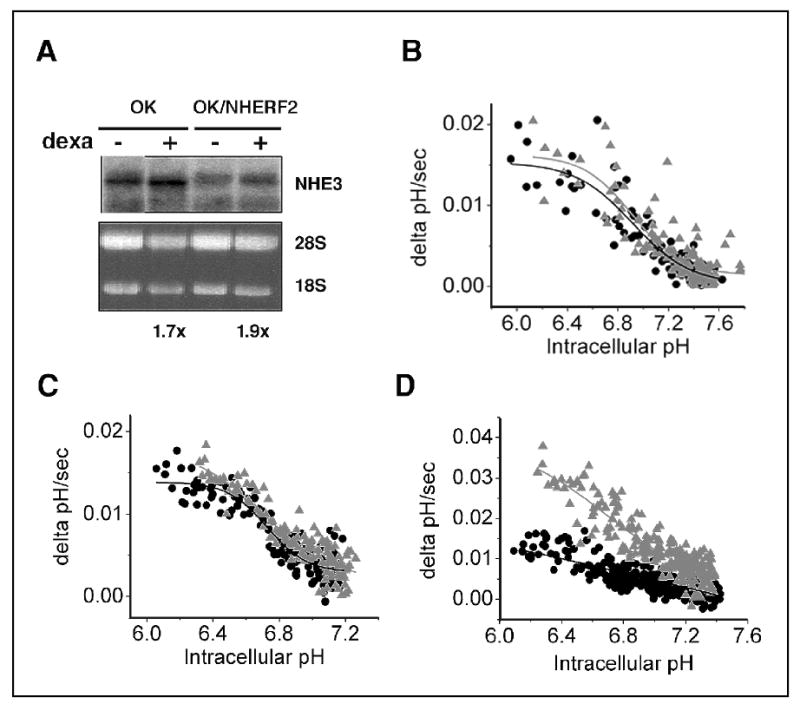

Our attempt to study the non-genomic effect of dexamethasone on NHE3 using OK cells, an opposum kidney cell line, led to unexpected findings. Incubation of OK cells with 1 μM dexamethasone for 24 hr failed to regulate NHE3 activity despite a two-fold increase in NHE3 mRNA abundance (Figure 2). OK cells express NHERF1 but lack any observable level of NHERF2 expression based on Western immunoblot and Northern analysis. A 24 hr dexamethasone treatment of OK cells stably transfected with NHERF2 led to a two-fold increase in NHE3 activity. In contrast, over-expression of NHERF1 in OK cells had no effect on NHE3 in response to dexamethasone.

Fig.2.

Effect of dexamethasone in OK cells. A. OK and OK/NHERF2 cells were incubated in 1μM dexamethasone for 24 hr. Northern blot analysis shows an increase in NHE3 mRNA abundance in both cell lines. B. OK, C. OK/NHERF1, D. OK/NHERF2, NHE3 activity is determined fluorometrically. •, control; ▴, dexamethasone treated. Reproduced with permission from ref (14).

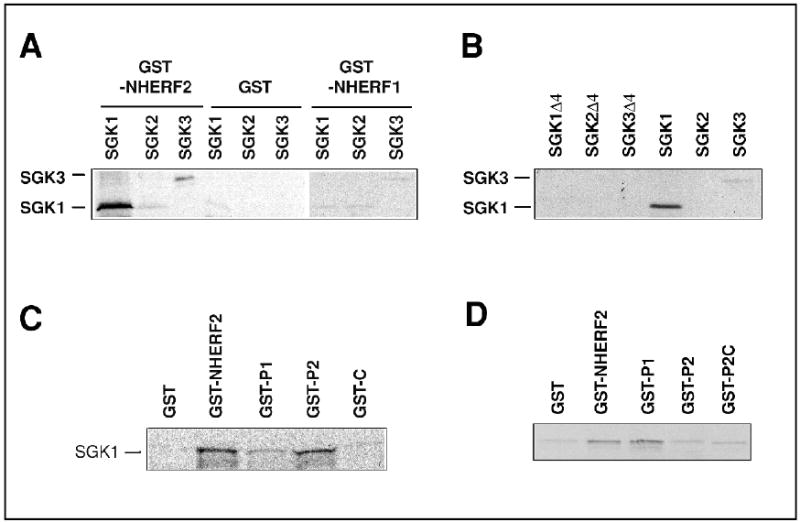

We speculated that a protein interacting with NHERF2 is necessary to mediate the dexamethasone effect in OK cells and searched GenBank for proteins interacting with NHERF2 and potentially mediate the dexamethasone effect. A potential candidate for this role was SGK1 with the C-terminal sequence of –DSFL and its known response to glucocorticoids. Specific interaction between SGK1 and NHERF2 was subsequently demonstrated. SGK1 specifically interacts with NHERF2 but not with NHERF1, consistent with the inability of NHERF1 to reconstitute the glucocorticoid-dependent stimulation of NHE3 in OK cells (Figure 3). Interestingly, SGK3 exhibits interaction with NHERF2 though at a lower affinity than SGK1. A recent study shows that SGK3 is targeted to endosomal compartments via a Phox homology (PX) domain, and the physiological significance of SGK3 interaction with NHERF2 remains unclear [91]. One possibility is the sequestration of SGK3 and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase I (PDK1) (see below). Consistent with the typical PDZ interaction, the interaction between SGK1 and NHERF2 is blunted when the C-terminal 4 amino acids of SGK1 is deleted.

Fig. 3.

In vitro interaction between SGK1 and NHERF2. (A) SGK1 and SGK3, but not SGK2 interacts with GST-NHERF2. There is no interaction with GST control or GST-NHERF1. (B) Deletion of the C-terminal 4 amino acids completely blocks the interaction with NHERF2. (C) SGK1 interacts with the second PDZ domains of NHERF2. Significantly weaker interaction with the first PDZ domain is also observed. (D) NHERF2 dimerizes via the first PDZ domain. Reproduced with permission from ref [14].

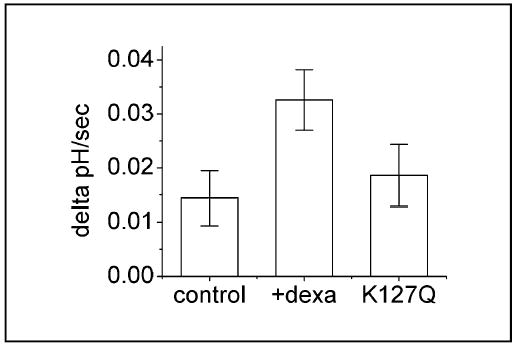

Co-expression of GST-SGK1 and NHERF2 in fibroblasts previously transfected with NHE3 resulted in stimulation of NHE3. But expression of NHERF2 or GST-SGK1 alone had no effect on NHE3 activity [12]. More importantly, co-expression of ”kinase-dead” SGK1 mutant with K127Q mutation markedly blocked the effect of dexamethasone demonstrating the necessity of SGK1 (Figure 4). Signaling pathways leading to stimulation of SGK1 is not fully resolved, but the activation of NHE3 by dexamethasone is phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) dependent since glucocorticoid-stimulation of NHE3 is blocked by LY294002, a PI3K blocker. However, because PI3K is essential for recycling of NHE3 between the plasma membrane and endosomal compartments, the direct role of PI3K requires further study [31, 92].

Fig.4.

SGK1 is necessary for the dexamethasone-dependent activation of NHE3. Hemagglutinin (HA) tagged SGK1/K127Q is expressed in OK cells. The stimulatory dexamethasone effect is markedly blocked by the presence of HA-SGK/K127Q. Reproduced with permission from ref (14).

The molecular nature of glucocorticoids-mediated stimulation of NHE3 is not known. Based on previously studies, it appears that glucocorticoid treatment increases the plasma membrane abundance of NHE3 [93]. The optimal consensus sequences for phosphorylation by SGK are R-x-R-x-x-S/T where S/T is the site of phosphorylation [94, 95]. Within NHE3, there is a single RxRxxS motif at amino acid 663, which is conserved in all NHE3 cloned from rabbit, rat, human and opossum. Our initial study suggests that NHE3 can be phosphorylated by SGK1 in vitro. However, it remains speculative that SGK1 phosphorylates NHE3 at this site in vivo to either directly increase its transport activity or to increase the plasma membrane distribution of NHE3.

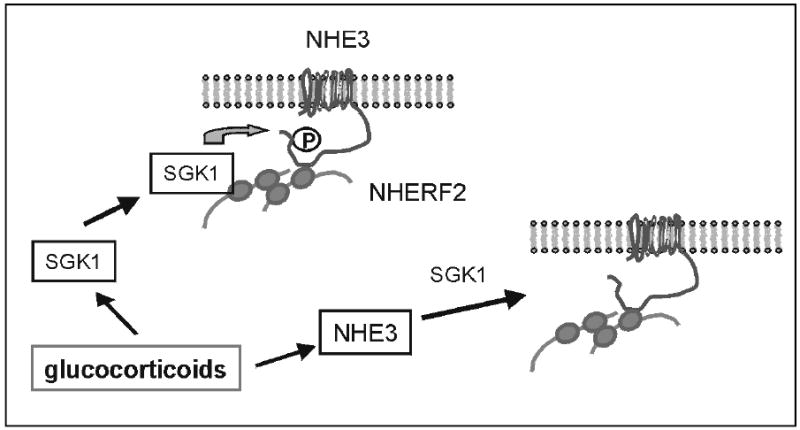

The glucocorticoid-activation of NHE3 appears to be bi-phasic (Figure 5). The initial acute phase does not require synthesis of NHE3 but most likely involves post-translational modification of pre-existing NHE3 proteins by SGK1. During the second chronic phase, newly synthesized NHE3 proteins are translocated into the plasma membrane and SGK1 and NHERF2 are required for this activation.

Fig. 5.

A model of glucocorticoid-dependent stimulation of NHE3.

The interaction between NHERF2 and NHE3 occurs via the second PDZ domain of NHERF2 and an internal region (aa 585 and 660) located within the cytoplasmic domain of NHE3 [52]. The second PDZ domain of NHERF2 also binds SGK1 [12]. If both the target protein and the kinase interact with the same motif of NHERF2, how the proteins involved are assembled? This is probably achieved by dimerization of NHERF2 [12, 43]. A homodimer of NHERF2 should be able to bind NHE3 on one end and SGK1 on the other end.

Does NHERF2 interact with PDK1?

SGK1 differs from the proto-oncogene akt/PKB since it lacks the Pleckstrin homology domain (PH) domain for membrane anchoring and its activation is independent of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate [94]. Because NHERF2 interacts with a large number of membrane spanning proteins, the interaction with NHERF2 may present a membrane anchoring mechanism for SGK1. This is the probable case for NHE3 regulation by SGK1, although further studies are needed to substantiate this speculation. Brickley et al. recently reported that the N-terminal domain of SGK1 mediates ubiquitin-mediated degradation in addition to facilitating the plasma membrane association of SGK1 in a breast cancer cell line [96]. It is plausible that the N-terminal region of SGK1 is required for general membrane targeting as suggested by Brickley and coworkers, but the association with NHERF2 is necessary for specific targeting of SGK1 to potential substrates.

The subfamily of protein kinases that includes cAMP and cGMP–dependent protein kinases and protein kinase C (AGC subfamily) requires phosphorylation in T-loop for activation. Similarly, SGK1 requires phosphorylation at Thr256 located within the T-loop by 3-phosphoinisitide-dependent kinase I (PDKI) [5, 94, 95]. Biondi et al. showed that interaction between PDK1 and some of its substrates is mediated via the PIF (PDK1-interacting fragment) motif [97]. PIF interacts with the PIF binding pocket of PDK1 that acts as a docking site and enhance the phosphorylation of its substrates. The PIF motif comprising the consensus amino acid sequences of F-x-x-F-S/T-Y is present in a number of kinases including SGK, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K), PKA and akt [97, 98].

Recently, Chun et al. identified a potential PIF motif at the C-terminus of NHERF2, F-S-N-F. By pull-down assay, Chun et al. demonstrated that PDK1 interacts with the C-terminal PIF motif of NHERF2, and NHERF2 co-imminoprecipitates with ectopically expressed SGK1 and PDK1 in COS-1 cells [99]. This interaction mediates activation of SGK1 by PDK1 by phosphorylation at Thr256 of SGK1. Although intriguing, the activation of SGK1 via the ternary complex formed by NHERF2, SGK1 and PDK1 cannot fully account for the enhanced phosphorylation at Thr256 by phosphorylation at Ser422 or the mutation of Ser422 to Asp [94, 95, 100].

Activation of ROMK1

In the distal regions of the kidney and colon, Na+ retention by epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) is balanced by efflux of K+ by K+ channel (ROMK) [101]. Coexpression of SGK1 and ENaC in X. laevis oocytes leads to stimulation of a Na+ current but no effect on ROMK-mediated K+ current was observed [8]. This is in contrast to the stimulative effect on voltage-gate K+ channel by SGK1 [102, 103]. However, colocalization of ROMK1 and NHERF2 in the collecting duct principal cells raises the possibility of concerted effect of SGK1 and NHERF2 [67]. In addition, ROMK1 lacks a PY motif that mediates interaction with the WW domain of Nedd4-2, but contains a PDZ binding motif at the C-terminal end further suggesting potential interaction with NHERF2. The coexpression of ROMK1 together with SGK1 and NHERF2 in in X. laevis oocytes led to a significant increase in the K+ current [104]. Co-expression of SGK1 and NHERF2 did not affect the I/V relation of ROMK1, although there was a small acidic shift of pKa of ROMK1 upon coexpression of SGK1 and NHERF2 compared to each protein alone.

It has recently been shown that SGK1 increases ENaC abundance and activity by altering the interaction between ENaC and the ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4-2 [9, 10]. Quantification of surface ROMK1 by surface biotinylation showed that ROMK1 abundance was increased by more than 200% when coexpressed with SGK1 and NHERF2 compared to SGK1 or NHERF2 alone [104]. Subsequent treatment with brefeldin A, which disrupts the budding process at the Golgi apparatus by inhibiting the essential assembly of coat proteins, suggested a stabilizing effect of SGK1/NHERF2 on ROMK1 protein in the plasma membrane [104]. However, whether NHERF2 stablilizes ROMK1 expression in the plasma membrane via the cytoskeletal linkage or impede the endocytic retrieval process is not known.

Perspectives

Considerable progress has been made in recent years in understating of the physiological roles of SGK1. In addition to acting as a pro-survival kinase similar to akt, it is evident that SGK1 plays a significant role in regulation of Na transport. The role of SGK1 in regulation of ENaC is now well accepted. Recent studies demonstrate that SGK1 is a major protein in regulation of ion transport and in some cases the presence of a scaffold protein NHERF2 is a prerequisite for stimulation. Future challenges entail identifying other ion channels and transporters regulated by SGK1 and NHERF2. But more importantly, physiological significances of such regulation need to be realized.

Acknowledgments

Work performed in the author’s laboratory was supported by NIH grant DK44484 and support from Emory University School of Medicine. Dr. Florian Lang is gratefully acknowledged for his collaboration and suggestion.

References

- 1.Webster MK, Goya L, Ge Y, Maiyar AC, Firestone GL. Characterization of SGK, a novel member of the serine/threonine protein kinase gene family which is transcriptionally induced by glucocorticoids and serum. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2031–2040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson R, Ainscough R, Anderson K, Baynes C, Berks M, Bonfield J, Burton J, Connell M, Copsey T, Cooper J, et al. 2.2 Mb of contiguous nucleotide sequence from chromosome III of C. elegans. Nature. 1994;368:32–38. doi: 10.1038/368032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casamayor A, Torrance PD, Kobayashi T, Thorner J, Alessi DR. Functional counterparts of mammalian protein kinases PDK1 and SGK in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1999;9:186–197. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Taniguchi R, Tanoue D, Yamaji T, Takematsu H, Mori K, Fujita T, Kawasaki T, Kozutsumi Y. Sli2 (Ypk1), a homologue of mammalian protein kinase SGK, is a downstream kinase in the sphingolipid-mediated signaling pathway of yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4411–4419. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4411-4419.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T, Deak M, Morrice N, Cohen P. Characterization of the structure and regulation of two novel isoforms of serum-and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase. Biochem J. 1999;344:189–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu D, Yang X, Songyang Z. Identification of CISK, a new member of the SGK kinase family that promotes IL-3-dependent survival. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1233–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00733-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang F, Cohen P. Regulation and physiological roles of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase isoforms. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:1–11. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.108.re17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SY, Bhargava A, Mastroberardino L, Meijer OC, Wang J, Buse P, Firestone GL, Verrey F, Pearce D. Epithelial sodium channel regulated by aldosterone-induced protein SGK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2514–2519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debonneville C, Flores SY, Kamynina E, Plant PJ, Tauxe C, Thomas MA, Munster C, Chraibi A, Pratt JH, Horisberger JD, Pearce D, Loffing J, Staub O. Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by SGK1 regulates epithelial Na+ channel cell surface expression. Embo J. 2001;20:7052–7059. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder PM, Olson DR, Thomas BC. SGK modulates Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of ENaC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loffing J, Zecevic M, Feraille E, Kaissling B, Asher C, Rossier BC, Firestone GL, Pearce D, Verrey F. Aldosterone induces rapid apical translocation of ENaC in early portion of renal collecting system: possible role of SGK. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F675–F682. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yun CC, Chen Y, Lang F. Glucocorticoid activation of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 revisited. The roles of SGK1 and NHERF2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7676–7683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun CHC, Tse C-M, Nath SK, Levine SA, Brant SR, Donowitz M. Mammalian Na+/H+ exchanger gene family:structure and function studies. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G1–G11. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Counillon L, Pouyssegur J. The expanding family of eucaryotic Na+/H+ exchangers. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numata M, Orlowski J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel (Na+,K+)/H+ exchanger localized to the trans-Golgi network. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17387–17394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moe OW. Acute regulation of proximal tubule apical membrane Na+/H+ exchanger NHE- 3: role of phosphorylation, protein trafficking, and regulatory factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2412–2425. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CW, Woodside M, Demaurex N, Yu FH, Plant P, Rotin D, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Proline-rich motifs of the Na+/H+ exchanger 2 isoform. Binding of Src homology domain 3 and role in apical targeting in epithelia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10481–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakabayashi S, Fafournoux P, Sardet C, Pouyssegur J. The Na+/H+ antiporter cytoplasmic domain mediates growth factor signals and contols “H+-sensing”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun CHC, Tse C-M, Donowitz M. Chimeric Na+/H+ exchanger: An epithelial membrane bound N-terminal domain requires an epithelial cytoplasmic C-terminal domain for regulation by protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10723–10727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P, Miller ML, Soleimani M, Gawenis LR, Riddle TM, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Wang T, Giebisch G, Aronson PS, Lorenz JN, Shull GE. Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet. 1998;19:282–285. doi: 10.1038/969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz JN, Schultheis PJ, Traynor T, Shull GE, Schnermann J. Micropuncture analysis of single-nephron function in NHE3-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F447–F453. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.3.F447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donowitz M, Welsh MJ. Ca2+ and cyclic AMP in regulation of intestinal Na, K, and Cl transport. Ann Rev Physiol. 1986;48:135–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgel N, Bojarski C, Mankertz J, Zeitz M, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Mechanisms of diarrhea in collagenous colitis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:433–443. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronson PS, Igarashi P. Molecular properties and physiological roles of the renal Na+/H+ exchanger. Curr Topics Memb Transport. 1986;26:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang T, Yang CL, Abbiati T, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE, Giebisch G, Aronson PS. Mechanism of proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption in NHE3 null mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F298–F302. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.2.F298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller T, Wijmenga C, Phillips AD, Janecke A, Houwen RH, Fischer H, Ellemunter H, Fruhwirth M, Offner F, Hofer S, Muller W, Booth IW, Heinz-Erian P. Congenital sodium diarrhea is an autosomal recessive disorder of sodium/proton exchange but unrelated to known candidate genes. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1506–1513. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Na+/H+ exchangers of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22373–22376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sardet C, Counillion L, Franchi A, Pouyssegur J. Growth factors induce phosphorylation of the Na+/H+ antiporter, a glycoprotein of 110-kD. Science. 1990;218:1219–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.2154036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurashima K, Yu FH, Cabado AG, Szabo EZ, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Identification of sites required for down-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28672–28679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H, Wiederkehr MR, Fan L, Collazo RL, Crowder LA, Moe OW. Acute inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-3 by cAMP. Role of protein kinase a and NHE-3 phosphoserines 552 and 605. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3978–3987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurashima K, Szabo EZ, Lukacs G, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Endosomal recycling of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 isoform is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20828–20836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho K-O, Hunt CA, Kennedy MB. The rat brain postsynaptiic density fraction contains a homolog of the Drosophila disc-large tumor suppressor protein. Neuron. 1992;9:929–942. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanning AS, Anderson JM. PDZ domains: fundamental building blocks in the organization of protein complexes at the plasma membrane. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:767–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Songyang Z, Fanning AS, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, Crompton A, Chan AC, Anderson JM, Cantley LC. Recognition of unique carboxyl-terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997;275:73–77. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle DA, Lee A, Lewis J, Kim W, Sheng M, MacKinnon R. Crystal structures of a complexed and peptide-free membrane protein-binding domain:molecular basis of peptide recognition by PDZ. Cell. 1996;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morais Cabral JH, Petosa C, Sutcliffe MJ, Raza S, Byron O, Poy F, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of a PDZ domain. Nature. 1996;382:649–652. doi: 10.1038/382649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hillier BJ, Christopherson KS, Prehoda KE, Bredt DS, Lim WA. Unexpected modes of PDZ domain scaffolding revealed by structure of nNOS-syntrophin complex. Science. 1999;284:812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karthikeyan S, Leung T, Ladias JA. Structural basis of the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor PDZ1 interaction with the carboxyl-terminal region of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19683–19686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider S, Buchert M, Georgiev O, Catimel B, Halford M, Stacker SA, Baechi T, Moelling K, Hovens CM. Mutagenesis and selection of PDZ domains that bind new protein targets. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:170–175. doi: 10.1038/6172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stricker NL, Christopherson KS, Yi BA, Schatz PJ, Raab RW, Dawes G, Bassett DE, Bredt DS, Li M. PDZ domain of neural nitric oxide synthase recognize novel C-terminal peptide sequences. Nature Biotech. 1997;15:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nbt0497-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall RA, Ostedgaard LS, Premont RT, Blitzer JT, Rahman N, Welsh MJ, Lefkowitz RJ. A C-terminal motif found in the beta2-adrenergic receptor, P2Y1 receptor and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator determines binding to the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor family of PDZ proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8496–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fouassier L, Yun CC, Fitz JG, Doctor RB. Evidence for ezrin-radixin-moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 (EBP50) self-association through PDZ-PDZ interactions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25039–25045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau AG, Hall RA. Oligomerization of nherf-1 and nherf-2 pdz domains: differential regulation by association with receptor carboxyl-termini and by phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8572–8580. doi: 10.1021/bi0103516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gee SH, Sekely SA, Lombardo C, Kurakin A, Froehner SC, Kay BK. Cyclic Peptides as Non-carboxyl-terminal Ligands of Syntrophin PDZ Domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21980–21987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinman EJ, Dubunsky WP, Shenolikar S. Reconstitution of cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulated renal Na+/H+ exchanger. J Memb Biol. 1988;101:11–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01872815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Wang Y, Shenolikar S. Characterization of a protein cofactor that mediated protein kinase A regulation of the renal brush border membrane Na+/H+ exchanger. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2143–2149. doi: 10.1172/JCI117903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yun CHC, Oh S, Zizak M, Steplock D, Tsao S, Tse CM, Weinman EJ, Donowitz M. cAMP-mediated inhibition of the epithelial brush border Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE3, requires an associated regulatory protein. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3010–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Yuan BN, Shenolikar S. Regulation of renal Na+/H+ exchanger by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1990;158:F1254–1258. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.5.F1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamprecht G, Weinman EJ, Yun CHC. The Role of NHERF and E3KARP in the cAMP-mediated Inhibition of NHE3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29972–29978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reczek D, Berryman M, Bretscher A. Identification of EBP50: A PDZ-containing phospho[rptein that associated with members of the ezrin-radixin-moesin family. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reczek D, Bretscher A. The carboxyl-terminal region of EBP50 binds to a site in the amino-terminal domain of ezrin that is masked in the dormant molecule. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18452–18458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yun CHC, Lamprecht G, Forster DV, Sidor A. NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein E3KARP binds the epithelial brush border Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 and the cytoskeletal protein ezrin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25856–25863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dransfield DT, Bradford AJ, Smith J, Martin M, Roy C, Mangeat PH, Goldenring JR. Ezrin is a cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:35–43. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zizak M, Lamprecht G, Steplock D, Tariq N, Shenolikar S, Donowitz M, Yun CH, Weinman EJ. cAMP-induced phosphorylation and inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) are dependent on the presence but not the phosphorylation of NHE regulatory factor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24753–24758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurashima K, D’Souza S, Szaszi K, Ramjeesingh R, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. The apical Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 is regulated by the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29843–29849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall RA, Premont RT, Chow A-W, Blitzer JT, Pitcher JA, Claing A, Stoffel RH, Barak LS, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ, Grinstein S, Lefkowitz RJ. The b2-adrenergic receptor interacts with the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor to control Na+/H+ exchange. Nature. 1998;392:626–630. doi: 10.1038/33458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohler PJ, Kreda SM, Boucher RC, Sudol M, Stutts MJ, Milgram SL. Yes-associated protein 65 localizes p62 (c-Yes) to the apical compartment of airway epithelia by association with EBP50. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:879–890. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maudsley S, Zamah AM, Rahman N, Blitzer JT, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Hall RA. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor association with Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor potentiates receptor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8352–8363. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8352-8363.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang Y, Tang J, Chen Z, Trost C, Flockerzi V, Li M, Ramesh V, Zhu MX. Association of mammalian trp4 and phospholipase C isozymes with a PDZ domain-containing protein, NHERF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37559–37564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahon MJ, Donowitz M, Yun CC, Segre GV. Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 directs parathyroid hormone 1 receptor signalling. Nature. 2002;417:858–861. doi: 10.1038/nature00816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sitaraman SV, Wang L, Wong M, Bruewer M, Hobert M, Yun CH, Merlin D, Madara JL. The Adenosine 2b Receptor Is Recruited to the Plasma Membrane and Associates with E3KARP and Ezrin upon Agonist Stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33188–33195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lamprecht G, Heil A, Baisch S, Lin-Wu E, Yun CC, Kalbacher H, Gregor M, Seidler U. The down regulated in adenoma (dra) gene product binds to the second PDZ domain of the NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein (E3KARP), potentially linking intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchange to Na+/H+ exchange. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12336–12342. doi: 10.1021/bi0259103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanai M, Mullen C, Podolsky DK. Intestinal trefoil factor induces inactivation of oxtracellular signal-regulated protein kinase in intestinal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:178–182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poulat F, Barbara P, Desclozeaux M, Soullier S, Moniot B, Bonneaud N, Boizet B, Berta P. The human testis determining factor SRY binds a nuclear factor containing PDZ protein interaction domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7167–7172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nguyen R, Reczek D, Bretscher A. Hierarchy of merlin and ezrin N- and C-terminal domain interactions in homo- and heterotypic associations and their relationship to binding of scaffolding proteins EBP50 and E3KARP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7621–7629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liedtke CM, Yun CH, Kyle N, Wang D. Protein kinase C epsilon-dependent regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator involves binding to a receptor for activated C kinase (RACK1) and RACK1 binding to Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22925–22933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wade JB, Welling PA, Donowitz M, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ. Differential renal distribution of NHERF isoforms and their colocalization with NHE3, ezrin, and ROMK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C192–C198. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fouassier L, Duan CY, Feranchak AP, Yun CH, Sutherland E, Simon F, Fitz JG, Doctor RB. Ezrin-radixin-moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 is expressed at the apical membrane of rat liver epithelia. Hepatology. 2001;33:166–176. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao TT, Deacon HW, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M. A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1999;401:286–290. doi: 10.1038/45816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swiatecka-Urban A, Duhaime M, Coutermarsh B, Karlson KH, Collawn J, Milewski M, Cutting GR, Guggino WB, Langford G, Stanton BA. PDZ domain interaction controls the endocytic recycling of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40099–40105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li J-G, Chen C, Liu-Chen L-Y. Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin-binding Phosphoprotein-50/Na+/H+ Exchanger Regulatory Factor (EBP50/NHERF) Blocks U50,488H-induced Down-regulation of the Human kappa Opioid Receptor by Enhancing Its Recycling Rate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27545–27552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Milewski MI, Mickle JE, Forrest JK, Stafford DM, Moyer BD, Cheng J, Guggino WB, Stanton BA, Cutting GR. A PDZ-binding motif is essential but not sufficient to localize the C terminus of CFTR to the apical membrane. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:719–726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moyer BD, Duhaime M, Shaw C, Denton J, Reynolds D, Karlson KH, Pfeiffer J, Wang S, Mickle JE, Milewski M, Cutting GR, Guggino WB, Li M, Stanton BA. The PDZ-interacting domain of cystic fibrosis trans-membrane conductance regulator is required for functional expression in the apical plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27069–27074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gisler SM, Stagljar I, Traebert M, Bacic D, Biber J, Murer H. Interaction of the type IIa Na/Pi cotransporter with PDZ proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9206–9213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hernando N, Deliot N, Gisler SM, Lederer E, Weinman EJ, Biber J, Murer H. PDZ-domain interactions and apical expression of type IIa Na/P(i) cotransporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11957–11962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shenolikar S, Voltz JW, Minkoff CM, Wade JB, Weinman EJ. Targeted disruption of the mouse NHERF-1 gene promotes internalization of proximal tubule sodium-phosphate cotransporter type IIa and renal phosphate wasting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11470–11475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162232699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takeda T, McQuistan T, Orlando RA, Farquhar MG. Loss of glomerular foot processes is associated with uncoupling of podocalyxin from the actin cytoskeleton. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:289–301. doi: 10.1172/JCI12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Y, Li J, Straight SW, Kershaw DB. PDZ domain-mediated interaction of rabbit podocalyxin and Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F1129–F1139. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00131.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:841–848. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Charney AN, Kinsey MD, Myers L, Giannella RA, Gots RE. (Na+-K+)-activated adenosine triphosphate in intestinal electrolyte transport. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:653–660. doi: 10.1172/JCI108135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Freiberg JM, Kinsella J, Sacktor B. Glucocorticoids increase the Na+/H+ exchange and decrease the Na+ gradient-dependent phosphate-uptake systems in renal brush border membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4932–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.16.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meneely R, Ghishan FK. Intestinal maturation in the rat: the effect of glucocorticoids on sodium, potassium, water and glucose absorption. Pediatr Res. 1982;16:776–778. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yun CHC, Gurubhagavatula S, Levine SA, Montgomery JLM, Cohen ME, Cragoe EJ, Pouyssegur J, Tse CM, Donowitz M. Glucocorticoid stimulation of ileal Na+ absorptive cell brush border Na+/H+ exchange and association with an increase in message for NHE-3, an epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger isoform. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cho JH, Musch MW, DePaoli AM, Bookstein CM, Xie Y, Burant CF, Rao M, Chang EB. Glucocorticoids regulate Na+/H+ exchange expression and activity in region- and tissue-specific manner. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C796–C803. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.3.C796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hulter HN, Licht JH, Bonner EL, Jr, Glynn RD, Sebastian A. Effects of glucocorticoid steroids on renal and systemic acid-base metabolism. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:F30–F43. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.239.1.F30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baum M, Moe OW, Gentry DL, Alpern RJ. Effect of glucocorticoids on renal cortical NHE-3 and NHE-1 mRNA. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F437–F442. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.3.F437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baum M, Cano A, Alpern RJ. Glucocorticoids stimulate Na+/H+ antiporter in OKP cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F1027–F1031. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.6.F1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moe OW Alpern RJ: Na+/H+ exchange in mamalian kidney; L. Fliegel: The Na+/H+ exchanger. R.G. Landes Company Chapman & Hall, 1996, pp 21–46.

- 89.Kandasamy RA, Orlowski J. Genomic organization and glucocorticoid transcriptional activation of the rat Na+/H+ exchanger Nhe3 gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10551–10559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cano A. Characterization of the rat NHE3 promoter. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F629–F636. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu J, Liu D, Gill G, Songyang Z. Regulation of cytokine-independent survival kinase (CISK) by the Phox homology domain and phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:699–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.D’Souza S, Garcia-Cabado A, Yu F, Teter K, Lukacs G, Skorecki K, Moore H-P, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. The epithelai sodium-hydrogen antiporter Na+/H+ exchanger 3 accumulates and is functional in recycling endosomes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2035–2043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Loffing J, Lotscher M, Kaissling B, Biber J, Murer H, Seikaly M, Alpern RJ, Levi M, Baum M, Moe OW. Renal Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-3 and Na-PO4 cotransporter NaPi-2 protein expression in glucocorticoid excess and deficient states. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1560–1567. doi: 10.1681/asn.v991560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kobayashi T, Cohen P. Activation of serum-and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase by agonists that activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase is mediated by 3- phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and PDK2. Biochem J. 1999;339:319–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Park J, Leong ML, Buse P, Maiyar AC, Firestone GL, Hemmings BA. Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) is a target of the PI 3- kinase-stimulated signaling pathway. Embo J. 1999;18:3024–3033. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brickley DR, Mikosz CA, Hagan CR, Conzen SD. Ubiquitin modification of serum and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase-1 (SGK-1) J Biol Chem. 2002:M207604200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Biondi RM, Kieloch A, Currie RA, Deak M, Alessi DR. The PIF-binding pocket in PDK1 is essential for activation of S6K and SGK, but not PKB. Embo J. 2001;20:4380–4390. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Biondi RM, Komander D, Thomas CC, Lizcano JM, Deak M, Alessi DR, van Aalten DM. High resolution crystal structure of the human PDK1 catalytic domain defines the regulatory phosphopeptide docking site. Embo J. 2002;21:4219–4228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chun J, Kwon T, Lee E, Suh PG, Choi EJ, Sun Kang S. The Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 mediates phosphorylation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Membrane distribution of sodium-hydrogen and chloride-bicarbonate exchangers in crypt and villus cell membrane from rabbit ileum. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:2158–2163. doi: 10.1172/JCI113838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Giebisch G. Renal potassium channels: function, regulation, and structure. Kidney Int. 2001;60:436–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gamper N, Fillon S, Huber SM, Feng Y, Kobayashi T, Cohen P, Lang F. IGF-1 up-regulates K+ channels via PI3-kinase, PDK1 and SGK1. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:625–634. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gamper N, Fillon S, Feng Y, Friedrich B, Lang PA, Henke G, Huber SM, Kobayashi T, Cohen P, Lang F. K+ channel activation by all three isoforms of serum- and glucocorticoid-dependent protein kinase SGK. Pflugers Arch. 2002;445:60–66. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yun CC, Palmada M, Embark HM, Fedorenko O, Feng Y, Henke G, Setiawan I, Boehmer C, Weinman EJ, Sandrasagra S, Korbmacher C, Cohen P, Pearce D, Lang F. The serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase SGK1 and the Na+/H+ exchange regulating factor NHERF2 synergize to stimulate the renal outer medullary K+ channel ROMK1. J Am Soc Nephr. 2002;13:2823–2830. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000035085.54451.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]