Abstract

Objective

To examine suicide attempts in an epidemiologically and genetically informative youth sample.

Method

3,416 Missouri female adolescent twins (85% participation rate) were interviewed from 1995 to 2000 with a telephone version of the Child Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, which includes a detailed suicidal behavior section. Mean age was 15.5 years at assessment.

Results

At least one suicide attempt was reported by 4.2% of the subjects. First suicide attempts were all made before age 18 (and at a mean age of 13.6). Major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, childhood physical abuse, social phobia, conduct disorder, and African-American ethnicity were the factors most associated with a suicide attempt history. Suicide attempt liability was familial, with genetic and shared environmental influences together accounting for 35% to 75% of the variance in risk. The twin/cotwin suicide attempt odds ratio was 5.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.75–17.8) for monozygotic twins and 4.0 (95% CI 1.1–14.7) for dizygotic twins after controlling for other psychiatric risk factors.

Conclusions

In women, the predisposition to attempt suicide seems usually to manifest itself first during adolescence. The data show that youth suicide attempts are familial and possibly influenced by genetic factors, even when controlling for other psychopathology.

Keywords: youth suicide attempts, twin studies, genetic epidemiology

“Suicide—however much may already have been said or done about it—is an event of human nature that demands everyone’s sympathy, and it should be dealt with anew in every era.”

—Goethe, 1776

In our era, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a call to heed youth suicide, the third leading cause of death in children and adolescents aged 10 to 19 years (U.S. Public Health Service, 1999). Studies have implicated common risk factors for completed youth suicides and suicide attempts, and it is estimated that from a third to a half of youth suicide completers have a known previous suicide attempt history (Brent et al., 1999; Marttunen et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 1996). Predictors of eventual suicide in any given suicide attempter are poor; thus investigations of youth suicide attempts across a wide spectrum of severity are needed. There are pronounced gender differences in youth suicidal behaviors (with male gender a risk factor for postpubertal suicide and female gender a risk factor for postpubertal suicide attempt), yet most empirical evidence does not suggest fundamental differences between risk factors for suicide and suicide attempts in males and females, although differences may exist in the weight of these factors (Brent et al., 1993, 1999; Groholt et al., 1999; Shaffer et al., 1996).

The 1999 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey estimated that 8.3% (10.9% for females and 5.7% for males) of U.S. high school students attempted suicide during the year preceding the survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2000). In contrast, retrospective surveys of adult samples suggest much lower rates of suicide attempts (lifetime prevalence of 4.6% reported for the U.S. population aged 15 to 54 years [Kessler et al., 1999]), which may reflect a significant recall bias in studies of primarily adult samples. With an increase in reports derived from general population samples (Fergusson and Lynskey, 1995; Fergusson et al., 2000; Garrison et al., 1993; Gould et al., 1998; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Reinherz et al., 1995), epidemiological factors associated with youth suicide attempts have become clearer. Youth suicide attempters drawn from community samples have high rates of psychopathology, congruent with the results of psychological autopsy studies showing that up to 90% of youth suicide victims suffered significant psychiatric problems (Brent et al., 1993). Lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) significantly increases the risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide completion (Brent et al., 1993; Gould et al., 1996, 1998). Disruptive disorders, alcohol and substance use problems, and child abuse history have also been found to be associated with suicide attempts. Researchers have suggested that the role of panic attacks (Gould et al., 1998; Pilowsky et al., 1999) and social phobia (Nelson et al., 2000) in youth suicidal behavior should be investigated further. Finally and importantly, unelucidated familial influences appear to contribute to youth suicidal behavior. There have been many reports of familial aggregation of suicidal behavior in adults (e.g., Egeland and Sussex, 1985) and a few family studies of youth suicidal behavior as well (Brent et al., 1996a; Bridge et al., 1997; Gould et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 1998), which all found familial factors even when controlling for psychiatric disorders.

Contagion effects have been cited as factors in suicidal behaviors (e.g., Maris, 1997). Although contagion appears to potentially precipitate suicidal behaviors in youth peer groups (Lewinsohn et al., 1994), it has not been found to play a major role in the familial aggregation of suicidal behaviors in either family, adoption, or twin studies (Brent et al., 1996b; Schulsinger et al., 1979; Statham et al., 1998). Biological traits common to adult violent suicide attempters have long implicated genetic factors in the etiology of suicidal behavior (Mann, 1987; Nielsen et al., 1994), but whether these findings generalize to epidemiological samples of youths is unclear. There are several adult reports of higher concordances for suicidal behavior in monozygotic (MZ) compared with dizygotic (DZ) twins (Haberlandt, 1967; Roy et al., 1991, 1995), suggesting genetic factors in the familial transmission of suicidal behavior. An analysis of suicidality data from 5,995 Australian male and female adult twins (Statham et al., 1998) estimated that genetic factors accounted for about 45% of the variance in lifetime suicidality (defined as persistent suicidal thoughts and/or suicide attempts). Youth twin-family studies have the marked advantage over non-twin family studies of discerning between genetic and environmental mechanisms of familial transmission of suicidal behavior. The goal of this report was to examine suicide attempts in a population-based, epidemiologically and genetically informative female adolescent twin sample.

METHOD

This study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All interviews were conducted by highly trained raters who appropriately obtained informed consent from subjects and their legal guardians when applicable. To minimize rater bias, no twins within a pair were interviewed by the same rater. Interviewers were always blind to respondents’ zygosity and cotwins’ interview responses. Methodology details are described in the report byHeath and others (1999).

Sample

Missouri Twin Register

The Missouri Twin Register is a population-based register derived from a systematic review of all Missouri birth records from 1968 onward. Computerized algorithms identify twins from state birth records. Parents of twins are then found by matching birth record information to driver’s license, marriage, and divorce databases. Missouri state law grants access to vital records and driver’s license records to those involved in research of relevance to public safety.

Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study

The Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study (MOAFTS), ascertained through the Missouri Twin Register, is a large, population-based, genetic-epidemiological, prospective twin-family study of alcohol use and problems and psychiatric comorbidity in young females. Using a cohort sequential design, in which new cohorts of 13-year-old twins were added each year, twins were aged 13, 15, 17, and 19 when first enrolled in the study. At least one parent was interviewed as well. Ninety-five percent of all female like-sex twin pairs identified from birth records were successfully located. Zygosity was determined with standard questions (Loehlin and Nichols, 1975) included in an initial parent telephone interview, a method shown to yield 95% accuracy when compared with genotyping (Eaves et al., 1989). With a participation rate of more than 85%, 3,416 female adolescent twins (approximately 55% MZ and 45% DZ) were interviewed between 1995 and 2000, for the first phase of the study. The age distribution of the sample at the time of assessment was 12 (0.5%), 13 (34.3%), 14 (8.5%), 15 (13.1%), 16 (7.6%), 17 (11.9%), 18 (5.8%), 19 (13.9%), 20 (3.5%), and 21–23 years (0.8%); mean age was 15.5 years. The sample included 13% minority subjects, almost exclusively African American, which reflects the minority composition of the Missouri general population. Twins adopted at birth were excluded to avoid unintentional exposures of adoption secrets. According to the CDC classification of family educational attainment (to classify the parent or guardian with the highest educational level), the sample consisted of 7.5% families “without high school diploma,” 40.4% “high school diploma without any college education,” 32.1% “some college education,” and 19.9% “degree from 4-year college or more.”

Assessments

Diagnostic Interview

The MOAFTS adolescent interview was a telephone adaptation of the Child Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (C-SSAGA), a polydiagnostic instrument developed for psychiatric genetics research and currently based on the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The C-SSAGA is derived from the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (Reich, 1996), for which there are good validity and reliability data (Reich, 2000). The MOAFTS interview has two versions: one for the younger cohort (12–15 years old) and one for the older cohort (16–22 years old). As illustrated in Table 1, the younger cohort’s interview excluded the section covering traumatic events. However, the Demographics and Home Environment segment, used for both age cohorts, contained this question about serious childhood physical abuse: “When you were 6 to 12, did any adult ever physically injure or hurt you? Examples of such injuries would include: broken bones, being hit so hard you developed bruises, or being burned or scalded with boiling water.”

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Diagnostic Interviews Used for the Younger Twins, Older Twins, and Parents

| Younger Cohort | Older Cohort | Parents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twins’ birth, early rearing, and zygosity | X | ||

| Demographics and home environment | X | X | X |

| School, work, relationships | X | X | X |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | X | X | |

| Separation anxiety disorder screen | X | ||

| ADHD/ODD/CD screen | X | ||

| Specific phobias, social phobia | X | X | |

| Health problems and health habits | X | X | |

| Parental smoking | X | ||

| Pregnancy with the twins | X | ||

| Smoking | X | X | |

| Alcohol use/dependence | X | X | |

| Parental alcohol use/dependence | X | ||

| Alcohol family history | X | X | X |

| Twin depression screen | X | X | X |

| Parental depression screen | X | ||

| Depression | X | X | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | X | X | |

| Panic disorder | X | ||

| Agoraphobia | X | ||

| Traumatic events | X | ||

| Suicidal thoughts and behaviors | X | X | |

| Conduct disorder | X | X | |

| Street drugs use | X | ||

| Relationship with friends/twin | X | X | |

| Family relationships | X | X | X |

| Family background | X | ||

| Subject comments | X | X | X |

Note: All psychiatric disorder assessments in this interview are based on the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder.

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

The assessment of lifetime suicidal behaviors was obtained via the separate Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors section, which has shown excellent interrater reliability (Bucholz et al., 1994). This section includes 17 question categories about the history of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts as well as self-mutilation (to control for self-injurious behaviors without suicidal intent). A family history of suicide and suicide attempts was obtained, but only from the twin subjects, not from their parents. Answers indicating an imminent risk of self-harm were flagged and followed up by a call from the principal investigator.

Diagnostic Procedures

The MOAFTS interview allows for lifetime diagnoses, which are essential in genetic epidemiology research. The diagnoses were made by programming computer algorithms based on DSM-IV criteria (including clinically significant functional impairment).

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were conducted with either the SAS system (SAS Institute, 1990), the Stata statistical software (StatCorp, 1999), or the Mx statistical software package (Neale, 1999). The total N for analyses was 3,401 subjects (out of 3,416) who completed the Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors section.

Age at Onset of Suicidal Behavior

Using the Kaplan-Meier method, we estimated the survival curves for lifetime suicidal thoughts, lifetime persistent suicidal thoughts, and lifetime plans.

Logistic Regression Analyses

Suicide attempt being the outcome variable, logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the contribution of psychiatric diagnoses and other factors statistically associated with suicide attempts. Dummy variables were created for age groups (15–16, 17–18, and ≥19) to control for the effect of increasing age on the variables, using twins aged 13–14 as the comparison group. Stata enabled the use of robust variance estimates to obtain 95% confidence intervals (CIs) adjusted for the statistical nonindependence of twin-pair observations.

Agreement Statistics

Twins’ self-reports of suicide attempts and cot-wins’ responses to the question, “Did your twin ever attempt suicide?” were compared by using as test statistics the κ and the Yule Y (which, unlike κ, is relatively insensitive to low base rates [Yule, 1912]). Twin/ cotwin agreements on suicide family history questions were examined with the κ test statistic.

Genetic Analyses

Genetic analyses were conducted with standard model-fitting procedures for the analysis of twin data (Neale and Cardon, 1992) as operationalized through Mx. The respective contributions of genetic and environmental factors to suicide attempts were estimated through the comparison of phenotypic resemblance in MZ twin pairs with that in DZ twin pairs. We first calculated the probandwise concordance and then the odds ratio (OR), representing the ratio of the risk of having a suicide attempt history among cotwins of suicide attempters and the risk of having a suicide attempt history among cot-wins of non–suicide attempters. The phenotypic variance was decomposed into three components: that caused by additive genetic factors (A), shared environmental factors (C) (such as the effect of being reared by the same parents), and unique or nonshared environmental factors (E) (individual environmental influences not shared by the twins). The most parsimonious model fitting the data was chosen, based on likelihood ratio comparisons of the goodness of fit of each model.

RESULTS

Suicidal Behaviors

Of 3,401 female adolescents, 4.2% (n = 143) reported at least one lifetime suicide attempt; 16.1% (n = 548) reported suicidal ideation, 6.8% (n = 232) reported persistent suicidal ideation lasting a whole day or more, 5% (n = 170) reported having made a specific suicide plan, and 4.7% (n = 160) reported self-mutilation other than a suicide attempt, with 20% of subjects in that last category also reporting a suicide attempt. Attempting suicide was more prevalent among African Americans (8%) and among the subjects in families with the lowest educational achievement, “without high school diploma” (9%). The mean number of suicide attempts per suicide attempter was 2.15 (SD = 3.4), and 35% of suicide attempters reported at least two suicide attempts. The methods of suicide attempt reported by the subjects were predominantly ingestions and wrist-cutting. Approximately 30% of the suicide attempters reported receiving medical care and 26% reported an admission to a hospital for “emotional stress or problems” as a consequence. The majority of suicide attempters (73.6%) reported they had believed their method of choice to be lethal and just over half (51.2%) really wanted to die at the time of attempt.

Age at Onset of Suicidal Behaviors

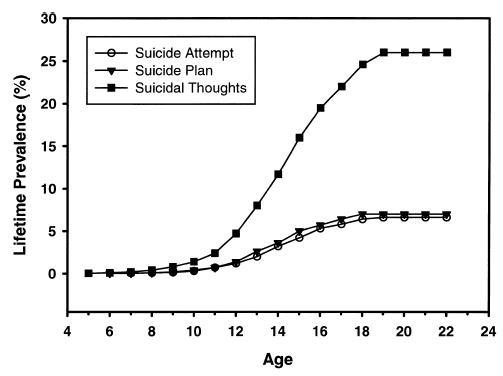

The mean age at first suicide attempt was 13.6 years (SD = 2.3) and 14.5 with adjustment for age at interview time. Because of the wide age distribution in the sample, a more informative perspective on the age at onset of suicide attempts is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves for lifetime suicidal thoughts, lifetime suicide plans, and lifetime suicide attempts. As shown in Figure 1, the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts reached a plateau of 6.6% by age 17. Seven percent reported having had a suicide plan by age 18, and 25.6% reported any suicidal ideation by age 19. To confirm that the plateau in prevalence seen for suicide attempts after age 17 was not a function of the age distribution in the sample, we estimated average age at onset of suicide attempts while stratifying respondents by age and obtained 14.8 for the twins who are 18, 15.4 for the twins who are 19, and 15 for the twins who are older than 20.

Fig. 1.

Lifetime prevalence rates of suicidal behaviors.

Comorbidity

Univariate Analysis

In Table 2, rates of suicide attempters’ DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses and other characteristics are compared with base rates found in non-attempters. ORs for lifetime histories of DSM-IV MDD, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence (AD), conduct disorder (CD), and childhood physical abuse were much greater than unity for suicide attempters compared with others, with or without adjustment for age.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Suicide Attempters and Nonattempters

| Univariate Analysis

|

Multivariate Analysis

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime History of | Rate (%) for Nonattempters | Rate (%) for Attempters | OR for Attempters | 95% CI | OR for Attempters | 95% CI |

| Alcohol abuse | 5.8 | 17.5 | 3.4 | 2.2–5.4 | NS | NS |

| Alcohol dependence | 5.2 | 19.7 | 4.5 | 2.9–7 | 2.8 | 1.5–5.2 |

| Any specific phobia | 10.0 | 31.0 | 3.9 | 2.6–5.7 | NS | NS |

| Conduct disorder | 0.7 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 5.5–22.2 | 4.0 | 1.2–12.8 |

| Generalized anxiety | 1.5 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 3.1–11.6 | NS | NS |

| Major depression | 7.2 | 48.2 | 12.1 | 8.4–17.3 | 8.8 | 5.8–13.7 |

| Social phobia | 12.5 | 35.7 | 4.0 | 2.8–5.8 | 2.2 | 1.4–3.5 |

| Child physical abuse | 2.2 | 15.7 | 8.1 | 4.9–13.6 | 3.5 | 1.6–7.3 |

| African-American ethnicity | 12.4 | 24.1 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.4 | 2.5 | 1.5–4.3 |

Note: Analyses controlled for age of subjects at the time of interview and subject’s parental educational attainment. OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; NS = not significant.

Multivariate Analysis

The associations with alcohol abuse, generalized anxiety disorder, simple phobia, and parental education were no longer significant when controlling for the other major predictors by multiple logistic regression, namely MDD (p < .001), childhood physical abuse (p < .001), social phobia (p < .001), AD (p < .001), African-American ethnicity (p < .001), and CD (p = .013). Notably, when limiting our analyses to the older cohort of twins (N = 1,200) who were asked comprehensively about their trauma history, a history of sexual molestation (OR = 4.0, 95% CI 2.0–8.0) and a history of physical abuse(OR = 3.7, 95% CI 1.7–7.9) were associated with suicide attempts even when controlling for the other major psychiatric predictors (MDD, AD, CD, and social phobia).

Salient Comorbidity Findings

Approximately 50% of those reporting at least one suicide attempt met criteria for lifetime MDD. Of adolescents meeting MDD criteria, 22% reported a history of at least one suicide attempt. Of these, 13 subjects (20%) made an attempt outside an MDD episode; however, they might have suffered from significant depressive symptoms at the time of their attempts. Compared with AD, social phobia, CD, and childhood physical abuse, MDD was the only psychiatric disorder statistically associated with persistent rather than just transient suicidal ideation (OR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.8–4.0). The combination of CD and MDD predicted a particularly high risk of suicide attempt, with eight of nine subjects meeting full diagnostic criteria for both disorders, reporting a history of at least one suicide attempt. Of a total of 197 alcohol-dependent subjects, 14.4% reported a suicide attempt history and 20% of those reporting a suicide attempt history also reported a history of AD. Suicide attempts preceded the onset of regular alcohol use by an average of 1.4 years (SD = 2.3 years) for AD subjects and 1.8 years (SD = 2.5) for non-AD subjects. Lifetime abstinence from alcohol was very significantly associated with not having attempted suicide (OR = 3.49 (95% CI 2.24–5.4) even when controlling for age at time of interview.

Familial Transmission

Family History

Although completed suicides were rare (1 sibling, 2 biological mothers, 4 biological fathers, 35 other biological family members, and 3 stepfathers), there were nevertheless significant associations between respondent suicide attempt and sibling’s suicide (OR = 10.9, 95% CI 1.6–74.7), biological father’s suicide (OR = 4.34, 95% CI 2.2–8.5), and biological mother’s suicide (OR = 5.4, 95% CI 2.5–11.2). Suicide attempts were not statistically associated with the suicides of non–first-degree relatives or of stepfathers. Table 3 summarizes the associations between suicide attempts reported by respondents, their cotwins’ self-reports of suicide attempts, and their reported family history of suicide attempts. Familial aggregation of suicide attempts in first-degree relatives is evident, and genetic effects are suggested by the comparison of data from MZ and DZ twins. Because twins were asked about their cotwins’ suicide attempt histories, the agreement between respondent and cotwin reports was examined. The resultant κ value was 0.45 (95% CI 0.32–0.58), and the Yule Y was 0.75 (95% CI 0.72–0.89). The hypothesis that MZ twins were possibly more aware of one another’s suicidal behavior history (which could arguably yield higher concordance rates for MZ pairs because of greater contagion effects) was examined, but agreement statistics for MZ twins compared with DZ twins were not statistically different. Of the 12 twin pairs concordant for suicide attempts, 4 pairs (2 MZ and 2 DZ pairs) had twins reporting the same age at onset of suicide attempt behavior, implying possible contagion. In the eight remaining pairs, differences in ages at onset ranged from 1 to 6 years, weakening the hypothesis of imitation as an explanation for these pairs’ concordances. Subject and cotwin agreement over the rest of the family history ranged from excellent for reported suicides (κ = 1 for maternal and paternal suicides and κ = 0.8 for other family members’ suicides) to moderate for reported suicide attempts (κ = 0.42 for siblings’ suicide attempts, κ = 0.52 for paternal suicide attempts, and κ = 0.57 for maternal suicide attempts).

TABLE 3.

Family History of Suicide Attempts

| Family Member Suicide Attempt History | Rate per 100 for Respondents Reporting a Suicide Attempt History | Rate per 100 for Respondents Denying a Suicide Attempt History |

|---|---|---|

| Cotwin (MZ) | 21.0 | 2.0 |

| Cotwin (DZ) | 13.2 | 3.0 |

| Other siblings | 13.8 | 3.51 |

| Biological mother | 9.7 | 1.7 |

| Biological father | 8.5 | 1.2 |

| Other relatives | 15.1 | 7.6 |

Note: MZ = monozygotic; DZ = dizygotic.

Genetic Analysis

The probandwise concordance for lifetime suicide attempts was 25% for MZ twins and 12.8% for DZ twins. The OR for twin/cotwin suicide attempt was 11.6 (95% CI 4.7–28.6) for MZ twins and 4.2 (95% CI 1.2–15.3) for DZ twins. Under the best-fitting model, estimates for A (additive genetic effects) were 48% (95% CI 0–73.2%), for E (unique or non-shared environmental factors) 44.1% (95% CI 27–67%), and for C (shared environmental effects) 8% (0–59%) (χ22 = 0.3, Akaike’s information criterion = −3.7, and p = .86, indicating a very good fit). These results confirm a familial liability to youth suicide attempt, with genetic and shared environmental factors together accounting for 33% to 73% of the variance in risk for suicide attempt. They only suggest that twin-pair concordance is partly genetically determined, and the effect is not statistically significant because of the relatively low base rates of suicide attempts causing very broad CIs.

Familial Transmission and Psychiatric Comorbidity

After controlling for proband phenotype (i.e., AD, CD, MDD, social phobia, and childhood physical abuse), cotwin suicide attempt remained strongly and specifically predictive of proband suicide attempt (MZ: OR = 5.6, 95% CI 1.75–17.8; DZ: OR = 4.0, 95% CI 1.1–14.7.) This points to specific familial and probably genetic effects in the familial transmission of suicide attempts. Notably, after controlling for both psychiatric comorbidity and cotwin history of suicide attempt, a cotwin psychiatric history was not significantly predictive of proband suicide attempt in either MZ or DZ pairs.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first reported twin study of youth suicide attempts. A few points merit discussion beside the familiality of suicidal behavior.

Onset of Suicidal Behaviors

In our study, first suicide attempts were uncommon after age 17. This does not appear to be just a function of age distribution in our sample. Velez and Cohen (1988) reported an increase in suicide attempts associated with ages 13 and 14 and a dramatic decline afterward in a smaller sample of adolescents. Our finding is somewhat different, in that we continue to see suicide attempts after mid-adolescence in our sample; however, there is no onset of suicide attempts after age 17. For comparison, we analyzed data from a new twin cohort of Australian twin pairs born 1964–1971 (mean age 30 at assessment) from the Australian Twin Registry: We found that the average age at onset of suicide attempts reported was 18.7 in adult women (N = 3,462) and 20.6 in adult men (N = 2,806) (Glowinski and Heath, unpublished data). Ages at first suicide attempts obtained from adults’ retrospective responses may be overestimates. This phenomenon, wherein reported age at onset tends to follow the age of survey respondents, is well established (e.g., Pickles et al., 1994). Our findings suggest that the predisposition to attempt suicide seems to manifest itself first usually (and sometimes only) during adolescence in women.

Comorbidity

As in other studies, we found a strong association between suicide attempts and psychopathology. The fact that suicide attempts generally preceded the onset of AD by a few years raises important questions about the relationship between AD and suicide attempts. Social phobia as already reported (Nelson et al., 2000) plays an independent role in increasing suicide attempt risk and should be routinely evaluated. The high risk conferred by the combination of MDD and CD has been described by others at least in male adolescents (Shaffer et al., 1996). Our finding that African-American ethnicity is a risk factor for suicide attempts in this sample has not been shown at a national level (CDC, 2000). However, the rates of completed suicides have risen so significantly in African-American male youths, that in contemporary birth cohorts African-American youths and white youths are almost at similar risk for suicide (Shaffer et al., 1994).

Familial Transmission

Our findings do not support a contagion hypothesis as a possible explanation for the higher suicide attempt concordance rate observed in MZ pairs. Our study suggests genetic factors in youth suicide attempts ascertained from a general population sample, though we do not have the power to exclude the possibility that familial influences are environmental rather than genetic. A logical next step will be the full examination of overlapping versus specific genetic and environmental factors in suicide attempts and comorbid psychiatric disorders, to confirm that as our data already suggest, there are genetic factors uniquely involved in the etiology of youth suicide attempts. Environmental and genetic family factors increasing the risk of exposure to abuse (Dinwiddie et al., 2000 ; McLaughlin et al., 2000), such as parental alcoholism, are associated with increased risk of offspring suicide attempt in our sample and will be explored with further analyses in conjunction with available parental psychopathology data. We find that 46.1% of the subjects reporting a suicide attempt had at least one alcohol-dependent parent. We did not examine the hypothesis that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts stem from the same versus different genetic and environmental factors. While this possibility was raised by the adult-twin-pair analyses of Statham and others (1998), testing this hypothesis is beyond the scope of the current paper.

Limitations

Our sample consisted of females only, and we cannot generalize our findings to males or suggest explanations of gender differences in youth suicidal behavior. Our study was geographically limited to twins born in Missouri, though many lived in different states. Our interview was done by telephone and was a cross-sectional assessment. As described, certain sections, notably the section covering history of sexual abuse, were omitted for younger adolescents (aged 12–15). Thus we can regrettably only report on the association of sexual abuse and suicide attempts in the older adolescent cohort. Family history of suicidal behaviors was provided by the adolescent subjects, and ideally it would have been additionally obtained from the parents. While information is available about other diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, other disorders assessed only through parental interviews will be addressed elsewhere. Finally, the assessment of lifetime suicidal behavior is made on the basis of retrospective recall. The temporal proximity to the events which the young subjects report and the detailed nature of the suicide section likely minimizes this bias to some extent.

Clinical Implications

Familial influences on adolescent suicide attempts are significant, even when other psychiatric disorders are controlled for. While a family history of suicide or suicide attempts in non–first-degree relatives may not be a great risk indicator of suicide attempt risk (given the relatively high base rates of subjects reporting that a relative had attempted suicide), a family history of suicide or suicide attempts in a first-degree relative appears to be quite predictive. While the (probable) genetic factors that convey an increased risk for suicidal behaviors are currently unknown, their elucidation will be a crucial step in improving prevention and treatment of youth suicide. It is not yet clear which types of child abuse are most predictive of suicide attempts, given the heterogeneity of assessments used in previous studies, the fact that some studies did not include comprehensive psychiatric assessments (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2000), and the fact that child abuse assessment presents complex methodological challenges (e.g., Brown et al., 2000; Glowinski, 2000). Nevertheless, child abuse (and we find effects for both sexual and physical abuse) is a potentially preventable risk factor justifying great clinical and research efforts. Children at highest genetic risk may also be at highest environmental risk of suicide attempts.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by NIH grants P50AA11998, R01AA09022, R37AA07728, and T32MH17104 and by the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation Fellowship Award in Depression. The authors acknowledge the helpful comments of the two anonymous reviewers of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Parts of this research were presented as a poster during the 1999 AACAP annual meeting in Chicago.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

- Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, Chen T, Chiapetta L. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Bridge J, Johnson BA, Connolly J. Suicidal behavior runs in families: a controlled family study of adolescent suicide victims. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996a;53:1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120085015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Moritz G, Bridge J, Perper J, Canobbio R. The impact of adolescent suicide on siblings and parents: a longitudinal follow up. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996b;26:323–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Brent DA, Johnson BA, Connolly J. Familial aggregation of psychiatric disorders in a community sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:628–636. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Assessing child maltreatment (letter) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:677–678. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1999. Mor Mortal Wkly Rep CDC Surveill Summ. 2000;49(No SS5):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie S, Heath AC, Dunne MP, et al. Early sexual abuse and lifetime psychopathology: a co-twin–control study. Psychol Med. 2000;30:41–52. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Eysenck HJ, Martin NG (1989), Genes, Culture and Personality: An Empirical Approach London: Academic Press

- Egeland JA, Sussex JN. Suicide and family loading for affective disorders. JAMA. 1985;254:915–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Childhood circumstances, adolescent adjustment, and suicide attempts in a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:612–622. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med. 2000;30:23–29. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, McKeown RE, Valois RF, Vincent ML. Aggression, substance use, and suicidal behaviors in high school students. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:179–184. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski AL. Assessing child maltreatment (letter) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:677. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethe JW (1776), In The Sorrows of Young Werther and Selected Writings. New York: Penguin Books, 1962

- Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1155–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groholt B, Ekeberg O, Wichstrom L, Haldorsen T. Sex differences in adolescent suicides in Norway, 1990–1992. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:295–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberlandt W. Aprotacion a la genetica del suicide. Folia Clin Int (Barc) 1967;17:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Madden PAF, Grant JD, McLaughlin TL, Todorov AA, Bucholz KK. Resiliency factors protecting against teenage alcohol use and smoking: influences of religion, religious involvement and values, and ethnicity in the Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study. Twin Res. 1999;2:145–155. doi: 10.1375/136905299320566013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Brent DA, Bridge J, Connolly J. The Familial Aggregation of Adolescent Suicide Attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Borges G, Walters E. Prevalence and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC, Nichols RC (1975), Heredity, Environment and Personality Austin: University of Texas Press

- Mann JJ. Psychobiologic predictors of suicide. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris RW. Social and familial risk factors in suicidal behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:519–550. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttunen MJ, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide among female adolescents: characteristics and comparison with males in the age group 13 to 22 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1297–1307. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin TL, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and pathogenic parenting in the childhood recollections of adult twin pairs. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1293–1302. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC (1999), Mx: Statistical Modeling Richmond: Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University ( http://views.vcu.edu/mx/)

- Neale MC, Cardon LR (1992), Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families, NATOASI Series Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Nelson EC, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, et al. Social phobia in a population-based female adolescent twin sample: co-morbidity and associated suicide-related symptoms. Psychol Med. 2000;30:797–804. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen D, Goldman D, Virkunnen M, Tokola R, Rawlings R, Linnoila M. Suicidality and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration associated with tryptophan hydroxylase polymorphism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:34–38. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Neale M, Simonoff E, et al. A simple method for censored age-of-onset data subject to recall bias: mothers’ reports of age of puberty in male twins. Behav Genet. 1994;24:457–468. doi: 10.1007/BF01076181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu L, Anthony JC. Panic attacks and suicide attempts in mid-adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;155:1545–1549. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich W (1996), Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) St Louis: Washington University Division of Child Psychiatry [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reich W. Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giacona RM, Silverman AB, et al. Early psychosocial risks for adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:599–611. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Segal NL, Centerwall B, Robinette D. Suicide in twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:29–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Segal NL, Sarchiapone M. Attempted suicide among living co-twins of twin suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1075–1076. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (1990), SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 6, fourth edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute

- Schulsinger R, Kety S, Rosenthal D, Wender P (1979), A family study of suicide. In: Origins, Prevention and Treatment of Affective Disorders, Schou M, Stromgren E, eds. New York: Academic Press, pp 277–287

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Hicks RC. Worsening suicide rate in black teenagers. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1810–1812. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatCorp (1999), Stata Statistical Software, release 6.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation

- Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med. 1998;28:839–855. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Public Health Service (1999), The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service

- Velez C, Cohen P. Suicidal behavior and ideation in a community sample of children: maternal and youth reports. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:349–356. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198805000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule GU. On the methods of measuring associations between two attributes. J R Stat Soc. 1912;75:581–642. [Google Scholar]