Abstract

Their glycolytic metabolism imposes an increased acid load upon tumour cells. The surplus protons are extruded by the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) which causes an extracellular acidification. It is not yet known by what mechanism extracellular pH (pHe) and NHE activity affect tumour cell migration and thus metastasis. We studied the impact of pHe and NHE activity on the motility of human melanoma (MV3) cells. Cells were seeded on/in collagen I matrices. Migration was monitored employing time lapse video microscopy and then quantified as the movement of the cell centre. Intracellular pH (pHi) was measured fluorometrically. Cell–matrix interactions were tested in cell adhesion assays and by the displacement of microbeads inside a collagen matrix. Migration depended on the integrin α2β1. Cells reached their maximum motility at pHe∼7.0. They hardly migrated at pHe 6.6 or 7.5, when NHE was inhibited, or when NHE activity was stimulated by loading cells with propionic acid. These procedures also caused characteristic changes in cell morphology and pHi. The changes in pHi, however, did not account for the changes in morphology and migratory behaviour. Migration and morphology more likely correlate with the strength of cell–matrix interactions. Adhesion was the strongest at pHe 6.6. It weakened at basic pHe, upon NHE inhibition, or upon blockage of the integrin α2β1. We propose that pHe and NHE activity affect migration of human melanoma cells by modulating cell–matrix interactions. Migration is hindered when the interaction is too strong (acidic pHe) or too weak (alkaline pHe or NHE inhibition).

Cell migration away from the primary tumour is a major step in metastasis. This multistep process requires sequential interaction between the invasive cell and the surrounding extracellular matrix. It is based on (i) extracellular matrix proteolysis by matrix metalloproteinases (Egeblad & Werb, 2002), (ii) directed reorganization of the cytoskeleton (Mitchison & Cramer, 1996), (iii) activity of ion channels and transporters such as Na+/H+ or Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (Klein et al. 2000; Schwab, 2001; Denker & Barber, 2002a, b; Saadoun et al. 2005), and (iv) a coordinated formation and release of focal adhesion contacts to the extracellular matrix mediated by integrin receptor molecules (Beningo et al. 2001; Jalali et al. 2001; Webb et al. 2002).

Focal adhesion contacts are stable cell–substrate interactions evolving from focal complexes which are characterized as small and transient cell interactions between the cell and the extracellular matrix (Friedl & Wolf, 2003). Focal contacts comprise integrins, the focal adhesion kinase (FAK), talin, vinculin, paxillin and other proteins attached to the actin filament network (Brakebusch & Fässler, 2003). The ubiquitously expressed Na+/H+ exchanger isoform, NHE1, is also part of these focal contacts at which it may directly interact with integrins (Schwartz et al. 1991; Grinstein et al. 1993; Plopper et al. 1995). In fibroblasts, NHE1 anchors the actin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane by its direct binding of ERM proteins (Denker et al. 2000; Denker & Barber, 2002a). A loss of this NHE1-dependent cytsokeletal anchoring impairs cell polarity and reduces the directionality in cell migration (Denker & Barber, 2002b). The transport activity of the NHE1 is stimulated during cell adhesion (Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz & Lechene, 1992) and is necessary for the assembly of focal adhesions (Tominaga & Barber, 1998).

However, the primary task of the NHE1 is the regulation of intracellular pH (pHi) and cell volume. NHE1 activity is of importance for many tumour cells (Lagarde et al. 1988; Rotin et al. 1989; Tannock & Rotin, 1989; McLean et al. 2000). The insufficient and/or inefficient tumour vascularization leads to a diminished O2 supply so that the metabolism of tumour cells is mostly glycolytic (Gulledge & Dewhirst, 1996; Helmlinger et al. 2002). Thus, tumour cells are often challenged by an increased acid load (Griffiths, 1991). The excess protons are extruded into the extracellular space by transport proteins such as the NHE1 (Yamagata & Tannock, 1996; Wahl et al. 2002) which then causes an acidification of the extracellular space (Tannock & Rotin, 1989). The role of the extracellular pH (pHe) in tumour cell migration, however, has not yet been established. NHE activation enhances the invasiveness of human breast cell carcinoma cells (Reshkin et al. 2000) implying a possible involvement of NHE and extracellular pH (pHe) in metastasis and tumour malignancy. We therefore investigated whether pHe and NHE activity modulate the motility of human melanoma cells on collagen matrices as well as in three-dimensional collagen lattices.

Methods

Cells and cell culture

The melanoma cell line MV3 (Van Muijen et al. 1991) was grown in bicarbonate-buffered RPMI 1640 (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Confluent MV3 cells were either plated onto (two-dimensional migration, 2D; for further details see below) or incorporated into (three-dimensional migration, 3D) collagen matrices except where stated otherwise.

Experimental solutions

Depending on the experimental set-up (experimental chamber airtight (5% CO2, 2D experiments) or open (0.03% CO2, 3D experiments)), experimental solutions and media were buffered with either NaHCO3 (2D) or with Hepes (3D). The amount of NaHCO3 to be added to the media was determined by the desired pH value.

Measurements of the intracellular pH were performed using Hepes-buffered Ringer solutions of different pH values containing (mmol l−1): 122.5 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.8 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 1.0 NaH2PO4.2H2O, 5.0 glucose, 10 Hepes. The pH was adjusted by adding 1 m NaOH. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution was used as solvent for the antibodies and as washing buffer as well. The PBS contained (mmol l−1): 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 8.1 Na2HPO4, 1.5 KH2PO4.

When applicable the NHE inhibitors ethyliso-propylamiloride (EIPA; final concentration: 10 μmol l−1 in 0.05% ethanol) or HOE642 (Cariporide; final concentration: 10 μmol l−1) were added. Rhodocetin, a component of snake venom that binds highly specifically to the integrin dimer α2β1 over a broad pH range (Eble & Tuckwell, 2003) was applied in a concentration of 5 μg ml−1.

Antibodies

The monoclonal anti-hVin-1 (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and the function blocking anti-human integrin β1 (4B7R) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Sant Cruz, CA, USA; Friedlander et al. 1996) were used for immunolabelling. Immunoblotting was performed with the anti-human integrin β1 from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA). A Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (both from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) served as the secondary antibodies.

Preparation of collagen matrices

One hundred mirolitres of 10× RPMI− 1640 and 100 μl 10× Hepes buffer (final Hepes concentration: 10 mmol l−1) were added to 800 μl collagen G solution (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany). When cells were embedded in collagen lattices for three-dimensional (3D) experiments the different pHe values were adjusted prior to the polymerization process by adding various amounts of 1 m NaOH. The cell density was kept at 250 000 cells ml−1. This cell-containing collagen solution polymerized within 3 h at 37°C in an open experimental chamber. When cell migration was observed on collagen matrices (2D) the pH of the cell free collagen mixture was always adjusted to pH 7.4 bearing in mind that the polymerization and self-assembly of collagen may be affected by the concentration of free protons (Williams et al. 1978; Freire & Coelho-Sampaio, 2000). An ensured reproducible collagen polymerization leading to a consistently fibrous matrix structure enabled us to exclude that the observed effects are based on pH-dependent differences in the matrix. The bottoms of culture flasks (12.5 cm2, Falcon) were covered with 500 μl collagen solution. About 100 μl of the same collagen solution were filled in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube in order to confirm the final pH of the gel after its polymerization by using a small pH electrode (Mettler, Toledo, Switzerland). The collagen was allowed to polymerize overnight at 37°C. Cells were seeded on this collagen matrix and allowed to adapt to different pH values varying from 6.4 to 7.5 for 3 h prior to recording.

The tractive power exerted by cells pulling on collagen fibrils was visualized by incorporating fluorescent microspheres (FluoSpheres, 1 μm, Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, USA) into the collagen matrix at a concentration of 4 × 107 beads ml−1 (Tamariz & Grinnell, 2002).

Videomicroscopy and computer-assisted cell tracking

The culture flasks (2D) or experimental chambers (3D) were put in heated chambers on stages of inverted microscopes (ID03 and Axiovert25, Carl Zeiss, Inc., Göttingen, Germany). Cell migration was recorded for 5 h at 37°C using video cameras (Models XC-ST70CE and XC-77CE, Hamamatsu/Sony, Japan) and PC-vision frame grabber boards (Hamamatsu). Images were taken in 10 min intervals controlled by a high performance image control system (HiPic, Hamamatsu Photonics Deutschland GmbH, Herrsching, Germany). The circumferences of the cells were labelled employing the AMIRA software (TGS Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The cell contours then served as the basis for further analysis. Each cell that remained in the visual field during the experiment without dividing or colliding with another cell was evaluated. Parameters such as the cell area, the structural index (SI) and the migratory speed were analysed using self-made JAVA programs and the NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Migration was determined as the movement of the cell centre per time unit, the speed was estimated from the 10 min time interval applying a three point difference quotient and the cell area was measured as the number of pixels. The structural index (SI) represents the cell shape. SI was calculated as follows:

where A is the area covered by the cell and p is the perimeter of A (Dunn & Brown, 1987, 1990). Values close to ‘1’ correspond to a spherical cell shape whereas values close to ‘0’ correspond to a spindle or a dendritic cell shape.

Measuring the intracellular pH (pHi)

pHi of MV3 cells was measured using video imaging techniques and the fluorescent pH indicator BCECF (Molecular Probes, OR, USA). Cells were treated as for migration experiments. They were resuspended in one of the Hepes-buffered experimental solutions containing EIPA or HOE642 where applicable. They were plated onto collagen coated coverslips and allowed to adapt for 3 h. Cells were then incubated in the respective experimental solution containing 2 μmol l−1 BCECF-AM for 1–2 min. The coverslips were placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Axiovert TV 100; Carl Zeiss, Inc., Göttingen, Germany) and continuously superfused with prewarmed Hepes-buffered Ringer solution. The excitation wavelength alternated between 488 and 460 nm, respectively, while the emitted fluorescence was monitored at 500 nm using an ICCD camera (Atto Bioscience, Rockville, MD, USA). Filter change and data acquisition were controlled by Attofluor software (Atto Bioscience). Fluorescence intensities were measured in 10 s intervals and corrected for background fluorescence. At the end of each experiment, the pHi measurements were calibrated by successively superfusing the MV3 cells with modified Ringer solutions of pH 7.5, 7.0 and 6.5 containing (mmol l−1): 125 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 20 Hepes, and 10 μmol l−1 nigericin (Sigma).

Cell adhesion

MV3 cells were resuspended in serum free RPMI media (RPMI−) of different pH (pH 6.4 to pH 7.5) with or without 10 μmol l−1 EIPA. Cells were then seeded in collagen (4 mg ml−1) coated 24-well plates at a density of 30 000 cells per well. After 60 min the media including the non-adhesive cells were removed. The remaining cells were washed with cold PBS buffer, then fixed and counted. In addition to their number the cells' morphology given as structural index (SI) and cell area was evaluated as described above. The software MetaVue (Universal Imaging) was used for taking images and counting.

Western blot of integrin β1

Confluent cells were transferred into serum-free bicarbonate-buffered RPMI 1640 medium of various pH values (7.5, 7.0 and 6.6) and allowed to adapt for ∼15 h. They were then washed with cold PBS and lysed at 4°C in lysis buffer containing (mmol l−1): 150 NaCl, 5.0 EDTA, 50 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 1.0 Pefabloc SC Plus (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), 1% Triton X-100, and 0.2% (v/v) of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P 8340). Lysates were scraped off 10 cm culture dishes (Falcon) and mixed with reducing sample buffer (4: 1, v/v) containing 500 mmol l−1 Tris, 100 mmol l−1 dithiothreitol, 8.5% SDS, 27.5% sucrose and 0.03% bromophenol blue indicator. SDS-PAGE was performed using acrylamide gels (7.5%) and a Minigel System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein (∼2 μg) were loaded. Electroblotting was performed at 0.8 mA cm−2 gel for 50 min. The nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) carrying the blotted proteins were bathed in 5% (w/v) milk in 0.1% (v/v) Tween in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with 0.1% Tween in PBS. Overnight incubation with the primary antibody (1: 600) at 4°C was followed by a 1 h incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1: 50 000) at room temperature. Blots were developed using an ECL immunoblotting detection reagent kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). In order to quantify β1 integrin expression, five blots were scanned and the number of pixels representing a marked band area was multiplied by the band's mean grey value calculated by the NIH ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were treated with cold 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min prior to fixation. Without this prepermeabilization step vinculin could hardly be labelled as the epitope was not accessible enough to the antibody. Cells were then fixed by 3.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Non-specific binding sites were blocked using 100 mm glycine in PBS and 10% (v/v) goat normal serum in PBS. After staining the cells with the hVIN-1 mAb or the integrin β1 (4B7R) mAb for 1 h and a Cy3-conjugated IgG for another hour (in a dilution of 1: 800 each), the slide preparations were fixed once again, washed in PBS and then covered with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were taken using an invert microscope (Axiovert200, Carl Zeiss, Inc., Göttingen, Germany), a digital camera (Model 9.0, RT-SE-Spot, Visitron Systems) and the MetaVue software.

Statistics

All experiments were repeated three to six times. Data are presented as the mean values ±s.e.m. The data were tested for significance employing Student's unpaired t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) where applicable. The level of significance was set at P < 0.01 except where otherwise stated.

Results

Cell migration depends on pHe and NHE activity

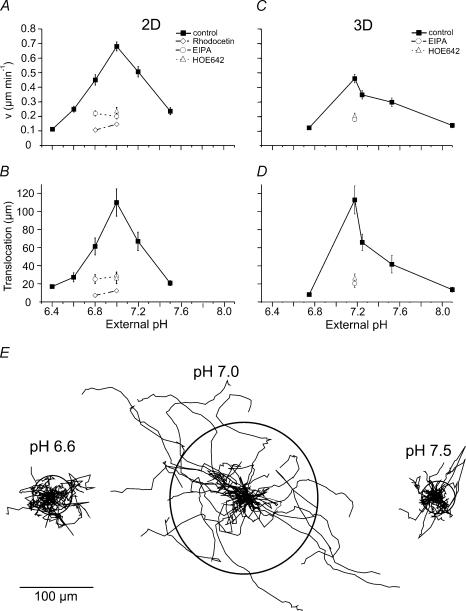

We calculated the average speed (given in μm min−1; Fig. 1A and C) and the mean translocation (= distance covered within 5 h; Fig. 1B, D and E) of migrating MV3 cells. Cells seeded on collagen (Fig. 1A) reached their maximum speed of 0.68 ± 0.03 μm min−1 at pHe 7.0 (n = 30 cells from three to five trials in each case). An increase in pHe to pH 7.5 or a decrease to pH 6.4 caused the migratory speed to decrease almost linearly to 0.11 ± 0.01 μm min−1 and 0.24 ± 0.02 μm min−1, respectively. The cells covered 109.9 ± 15.1 μm at pHe 7.0, but only 20.7 ± 2.8 μm and 27.2 ± 5 μm at pHe 7.5 and pHe 6.6, respectively (Fig. 1B and E). NHE inhibition by EIPA or HOE642 decreased speed and translocation by up to 70% at pHe 7.0 (0.2 ± 0.02 μm min−1, 28 ± 3.7 μm within 5 h). Extracellular acidification to pHe 6.8 did not amplify the inhibitory effect of NHE blockage on cell migration. However, migration was inhibited when cells were exposed to propionic acid (15 mmol l−1) while the extracellular pH was kept constant at pHe 7.0. Protonated weak organic acids such as propionic acid permeate the plasma membrane and dissociate rapidly in the cytosol causing an initial intracellular acidification and an increase in NHE activity (Boron, 1983; Klein et al. 2000). After a 3 h exposure of MV3 cells to 15 mmol l−1 sodium propionate at a constant pHe of 7.0 and a pHi of 7.1 ± 0.05 (n = 38 cells from four trials, for details see below) the migratory speed on a 2D matrix was reduced to 0.07 ± 0.01 μm min−1 (n = 36 cells from eight different trials). The translocation within 5 h was only 18.5 ± 2.77 μm (cf. Fig. 1A and B). Additional exposure of acidified cells to 10 μmol l−1 HOE642 led to a further decrease in the migratory speed (0.03 ± 0.004 μm min−1, n = 40 cells from 4 different trials, cf. Fig. 1A and B) and the cells' translocation (6.45 ± 0.9 μm (5 h)−1).

Figure 1. Migratory speed, translocation and trajectories of MV3 cells depend on pHe.

Cells were either seeded on collagen matrices (2D: A, B and E) or incorporated in collagen lattices (3D: C and D; Supplemental material video 1; video 2; video 3) and recorded for 5 h. Migratory speed (A and C) and translocation within 5 h (B and D) under control conditions (▪), after the application of EIPA (○; video 4) or HOE642 (▵; video 5) and upon treatment with rhodocetin (grey diamonds). n varied between 30 (2D) and 10–20 (3D) cells taken from three to five different trials. E, trajectories of MV3 cells migrating on collagen (2D) at different pHe values. Trajectories obtained under the same experimental conditions were standardized. They all begin at the same starting post represented by the centre of a circle. The radii of the circles represent the mean distances covered within 5 h. n = 30 cells each, taken from three to five different trials.

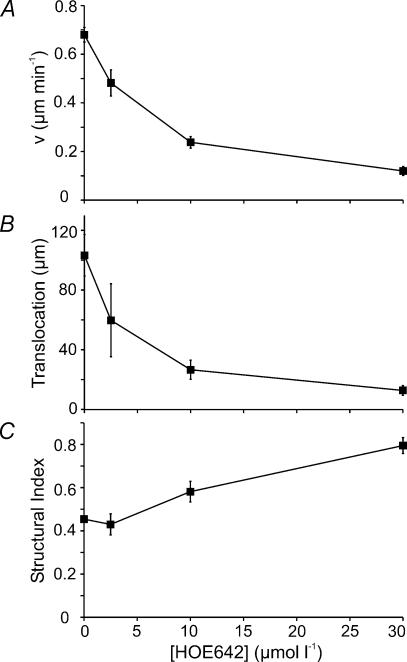

Cells embedded in three-dimensional collagen lattices (Fig. 1C and D) behaved similarly (n = 10–20 cells from three to five trials in each case). They reached their maximum speed and translocation at pHe 7.18: 0.46 ± 0.03 μm min−1 and 112.9 ± 15.5 μm (n = 16; Supplemental material video 1). When pHe was reduced to pH 6.75 (video 2) or increased to pH 8.1 (video 3) migratory speed and translocation decreased significantly (at pHe 6.75: 0.12 ± 0.01 μm min−1 and 8.2 ± 1.8 μm (n = 10); at pHe 8.1: 0.14 ± 0.02 μm min−1 and 13.6 ± 2.7 μm (n = 15)). NHE inhibition by EIPA (video 4) or HOE642 (Cariporide; video 5) decreased speed and translocation by 55%: 0.20 ± 0.02 μm min−1 and 20.6 ± 4.6 μm (EIPA; n = 20), and 0.18 ± 0.02 μm min−1 and 26.7 ± 4.3 μm (HOE642, n = 20). HOE642 inhibits cell migration (Fig. 2A and B) at pHe 7.0 with an IC50 of ∼5 μmol l−1 and affects cell morphology (Fig. 2C) in a dose-dependent manner indicating that NHE activity plays a major role in controlling cell migration and morphology. Most likely it is the isoform NHE1 as revealed by Western blot analysis (data not shown). Also, at the concentration used in this study HOE642 is unlikely to effectively inhibit the resistant NHE isoforms such as NHE3 (Scholz et al. 1995). The IC50 value for HOE642 effects on the human NHE3 is 900 μmol l−1 (Schwark et al. 1998).

Figure 2. HOE642 affects the migratory speed (v), translocation and morphology (SI) of MV3 cells in a dose-dependent manner.

pHe was 7.0 throughout. n = 20–30 cells from three to five different trials in each case.

Speed and translocation were reduced to a similar extent when the integrin dimer α2β1 was specifically blocked by rhodocetin (Fig. 1). Moreover, Table 1 shows that, regardless of pHe, cells seeded on poly l-lysine hardly migrated and that they did not spread but remained spherical. These observations confirm the finding by Maaser et al. (1999) that in MV3 cells the integrin α2β1 is indispensable for cell migration on collagen.

Table 1.

The migratory behaviour of cells seeded on poly l-lysine does not depend on pHe

| pH 6.6 | pH 6.8 | pH 7.2 | pH 7.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| v (μm min−1)coll | 0.25 ± 0.02 (30) | 0.45 ± 0.036 (30) | 0.51 ± 0.036 (30) | 0.24 ± 0.024 (30) |

| v (μm min−1)poly | 0.06 ± 0.007 (29)* | 0.04 ± 0.005 (16)* | 0.04 ± 0.005 (23)* | 0.05 ± 0.004 (19)* |

| Translocation (μm)coll | 27.2 ± 5 (30) | 61.3 ± 9.4 (30) | 66.9 ± 10.1 (30) | 20.7 ± 2.8 (30) |

| Translocation (μm)poly | 4.39 ± 0.41 (29)* | 5.8 ± 0.8 (16)* | 3.49 ± 0.69 (23)* | 7.07 ± 0.54 (19)* |

| Structural index (SI)coll | 0.37 ± 0.02 (30) | 0.34 ± 0.02 (30) | 0.51 ± 0.02 (30) | 0.73 ± 0.02 (30) |

| Structural index (SI)poly | 0.86 ± 0.02 (29)* | 0.84 ± 0.03 (16)* | 0.87 ± 0.03 (23)* | 0.88 ± 0.01 (19)* |

The number in parentheses represents the number of analysed cells from three different trials for poly l-lysine (poly) and up to five different trials for collagen (coll).

P < 0.01; poly l-lysine versus collagen.

Cell morphology is determined by pHe and/or by NHE activity

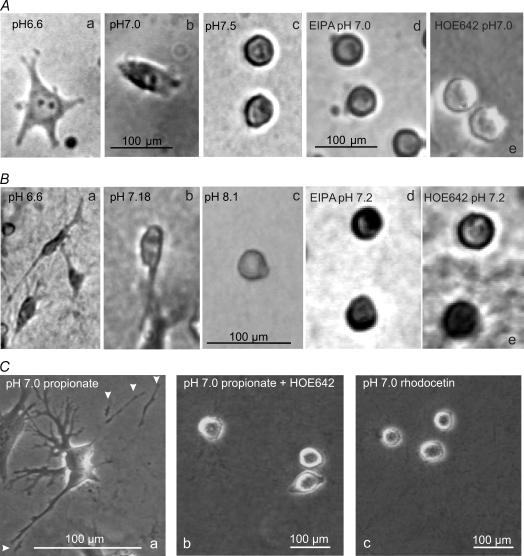

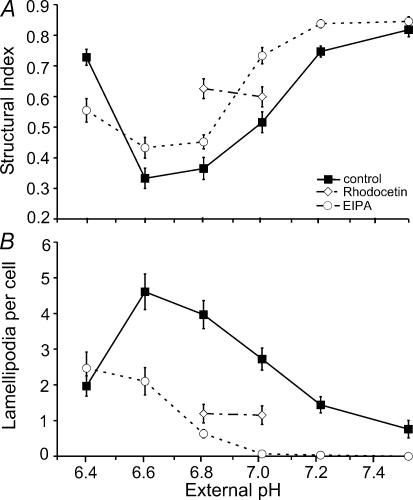

Since changes in motility and migratory behaviour might be accompanied by morphological modifications we checked whether pHe and NHE activity also affected the cell morphology. As shown in Fig. 3, cells were dendritic at pHe 6.6 or of ameboid shape at pHe 7.0 whereas they were spherical at pHe 7.5 (2D) or pHe 8.1 (3D) and in the presence of NHE inhibitors. These morphological properties were quantified by calculating the structural index (SI) and counting the lamellipodia per cell (n = 30 cells from five trials in each case) 60 min after seeding onto collagen (Fig. 4). SI dropped from 0.82 ± 0.02 to 0.33 ± 0.03 as pHe decreased from pH 7.5 to pH 6.6. It then rose to 0.73 ± 0.03 as pHe was further reduced to 6.4. In the presence of EIPA the entire graph is shifted to more acidic values. At pHe 6.4 EIPA-treated cells were less rounded than the control cells. The number of lamellipodia per cell increased from 0.8 ± 0.3 cell−1 to 4.6 ± 0.5 cell−1 as pHe decreased from pH 7.5 to pH 6.6 (Fig. 4B). It decreased to 2.0 ± 0.3 when pHe was further reduced to 6.4. The application of EIPA caused a significant drop in the number of lamellipodia in cells that had been exposed to pH values varying between 6.6 and 7.5. Interestingly, in EIPA-treated cells the number of lamelliopodia continuously rose from 0 ± 0 to 2.5 ± 0.5 cell−1 as pHe decreased from pH 7.5 to pH 6.4. At pH 6.4 the number of lamellipodia was the same in EIPA-treated and in control cells (2.5 ± 0.5 cell−1 and 2.0 ± 0.3 cell−1, respectively). This finding suggests that the effect of NHE inhibition on the formation of lamellipodia can at least partially be compensated by lowering pHe. Similar results were obtained when the morphology of MV3 cells was analysed under the same conditions 180 min after seeding (data not shown). Sodium propionate (15 mmol l−1) had an even more distinct effect on the morphology than had an acid pHe. SI dropped to 0.11 ± 0.01 and cells developed numerous long lamellipodia which they tended to shed (Fig. 3C). This effect could be reversed by the simultaneous application of HOE642 (SI = 0.61 ± 0.1).

Figure 3. Morphology of MV3 cells.

A and B, cells seeded on collagen matrices (A) or incorporated into collagen lattices (B) after a 3 h exposure to different pHe values (a–c; Supplemental material videos 1–3) or 3 h after the application of 10 μmol l−1 EIPA (d; video 4) or 10 μmol l−1 HOE642 (e; video 5) at pHe 7.2. C, cells seeded on collagen matrices were exposed to sodium propionate (a) or to sodium propionate plus HOE642 (b) or treated with rhodocetin (c). The arrow heads in Ca indicate shedding of cell processes.

Figure 4. Structural index (A) and formation of lamellipodia (B) in MV3 cells depend on pHe and NHE activity.

Cells were seeded on collagen and incubated in RPMI− media of different pHe in the presence (○) or absence (▪) of 10 μmol l−1 EIPA or in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 rhodocetin (grey diamonds). The parameters were determined at t = 60 after seeding. The results shown in A and B were obtained from the same cells. Each data point represents the mean ±s.e.m. obtained from n = 50 cells from five different experiments (5 cells per area (2 × 105μm2), 2 areas per experiment).

In the presence of rhodocetin cells developed none or only one lamellipodium and remained rather round (Figs 3C and 4). This suggests that the interaction between integrin α2β1 and the extracellular matrix is needed to form processes.

pHe and NHE activity determine pHi

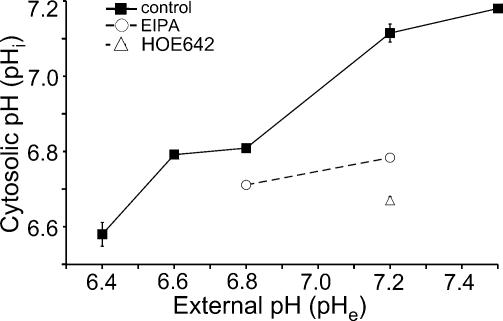

The previous paragraphs showed that the extracellular pH and/or NHE activity have a strong impact on migration and morphology of MV3 cells. Thereupon we measured the resulting changes of the intracellular pH (pHi) in order to determine whether they could account for the altered migratory behaviour. The results are summarized in Fig. 5. pHi decreased as pHe decreased. pHi was 7.18 ± 0.01 (n = 58) in cells exposed to pHe 7.5 while it was 6.58 ± 0.03 (n = 59) at pHe 6.4. pHi of HOE642 treated cells was 6.67 ± 0.01 (n = 45) at pHe 7.2. pHi of EIPA-treated cells was 6.78 ± 0.01 (n = 21) at pHe 7.2 and it significantly decreased further to 6.71 ± 0.01 (n = 29) at pHe 6.8. Thus, in contrast to migration, the effects of EIPA and extracellular acidification on pHi are additive. After a 3 h exposure of MV3 cells to sodium propionate (15 mmol l−1) at pHe 7.0, pHi was 7.1 ± 0.05 (n = 38 cells from four trials). Additional exposure of acidified cells to 10 μmol l−1 HOE642 led to a decrease in pHi (pH 6.69 ± 0.04, n = 30 cells from three trials).

Figure 5. Cytosolic pH (pHi) of MV3 cells depends on the external pH (pHe) or NHE activity.

pHi was measured after a 3 h exposure to different pHe values (▪) or 3 h after the addition of 10 μmol l−1 EIPA (at pHe 6.8 and 7.2; ○) and 10 μmol l−1 HOE642 (at pHe 7.2; ▵). n varied between 21 and 106 cells from three to six trials.

It is conspicious that pHi, migration and morphology of MV3 cells do not directly correlate with one another. An intracellular acidification caused by a low pHe or by NHE inhibition is associated with completely different morphologies. Conversely, intracellular alkalinization by a high pHe or intracellular acidification by NHE inhibition produce identical morphological changes. Similar discrepancies were found comparing control cells with propionate-treated cells. Thus, alterations of pHi alone cannot explain the observed changes in migration and morphology.

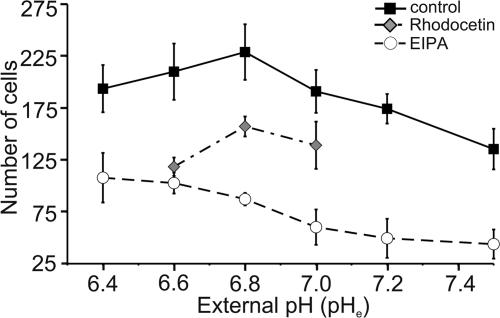

Adhesion to the extracellular matrix increases as pHe decreases

In this series of experiments we tested whether the observed changes in migration and morphology could be related to a pHe- and/or NHE-mediated modulation of the cell–matrix interaction. To this end we performed adhesion assays at different pHe values varying from 6.4 to 7.5 in the presence and absence of EIPA (Fig. 6). The number of adhesive cells increased by 70% (P < 0.02) from 135 ± 20 cells/area (n = 6 trials) to 229 ± 27 cells/area (n = 6) as pHe was lowered from pH 7.5 to pH 6.8. A further reduction of pHe below pH 6.8, however, led to a slight decrease in the number of adhesive cells (194 ± 23 cells/area; n = 6). This decrease was not caused by acid-induced cell death or apoptosis since MV3 cells can easily be cultured at pH 6.6 for several months (data not shown). Inhibiting NHE with EIPA caused a significant drop in the number of adhesive cells by 44% at pH 6.4 up to 62% at pH 6.8. Interestingly, the adhesion of EIPA-treated cells continuously increased as pHe decreased. This indicates that an acidic pHe may compensate for the effect of NHE inhibition on cell adhesion. Cell adhesion could also be reduced by rhodocetin (Fig. 6). The number of adhesive cells upon rhodocetin treatment at pHe 6.8 or 7.0 resembled that of untreated cells at pHe 7.5.

Figure 6. Adhesion of MV3 cells to a collagen matrix depends on pHe and NHE activity.

The adhesiveness is represented by the number of cells that remained stuck to the collagen matrix after washing with PBS 60 min after seeding. Cells were treated with rhodocetin (grey diamonds, n = 3 trials, four areas per trial) or exposed to solutions of various pHe with (○, n = 4 trials, two areas per trial) or without (▪, n = 6 trials, two areas per trial) 10 μmol l−1 EIPA.

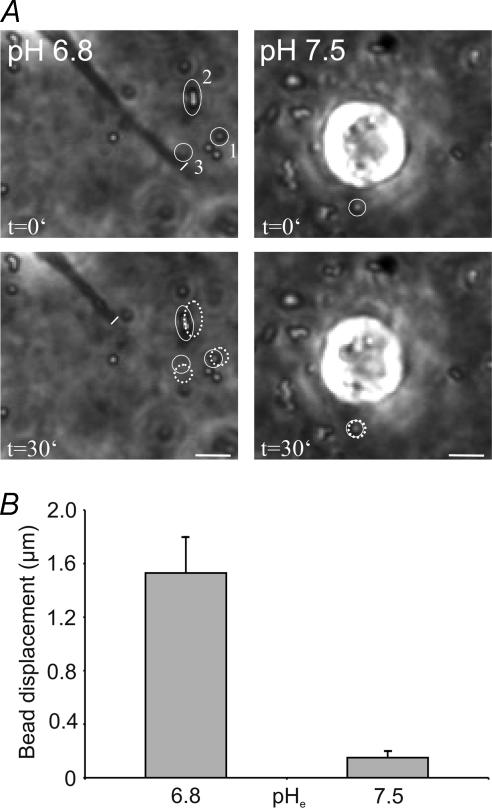

The pHe dependence of the cell–matrix interaction could as well be demonstrated in another set of experiments. Cells incorporated into a collagen matrix and exposed to low pHe values (pH 6.8) pulled on the collagen matrix when they retracted their processes (Fig. 7). The cell-induced movement of the matrix was made visible by the displacement of microbeads that were incorporated in the matrix. Within 30 min the microbeads were displaced by 1.53 ± 0.27 μm at pHe 6.8 (n = 12 beads from four different trials) as opposed to only 0.15 ± 0.05 when cells were observed at pHe 7.5 (n = 15). These observations indicate that the cell surface/collagen interaction is stronger at lower pHe values and weaker at higher pHe values.

Figure 7. Cells exposed to low pHe values (pH 6.8) pull on the matrix when they retract their lamellipodia.

This is shown by the displacement of microbeads incorporated in the collagen matrix. A, bead 1 moved 1.1 μm within 30 min, beads 2 and 3 were displaced by 1.3 and 1.9 μm, respectively. At high pHe (pH 7.5) cells did not exert traction on the matrix. The labelled bead moved 0.2 μm. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, statistics of bead displacement at pHe 6.8 (n = 12 beads from four different trials, three beads per cell) and at pHe 7.5 (n = 15 beads from five different trials, three beads per cell).

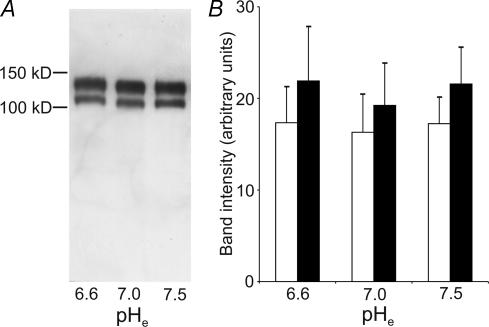

pHe does not stimulate the expression of integrin β1

The integrin dimer α2β1 mediates cell adhesion, spreading and migration in MV3 cells (Friedl et al. 1998; Maaser et al. 1999; Friedl & Bröcker, 2000). We therefore tested whether the pHe-dependent strengthening of the cell–matrix interaction was due to a pHe-dependent up-regulation of the integrin β1-expression. However, immunoblots revealed no pHe induced differences in the overall expression of integrin β1 (Fig. 8). The intensity of the two integrin β1 bands at 110 and 130 kDa remained the same regardless of the pHe cells had been exposed to prior to cell lysis.

Figure 8. In MV3 cells the expression of integrin β1 does not depend on pHe.

A, Western blot of human integrin β1. Equal amounts of protein (2 μg) were loaded. B, the 110 kDa (precursor protein, open bars) as well as the 130 kDa bands (mature protein, filled bars) did not differ depending on pHe (mean ±s.e.m.; n = 5 blots).

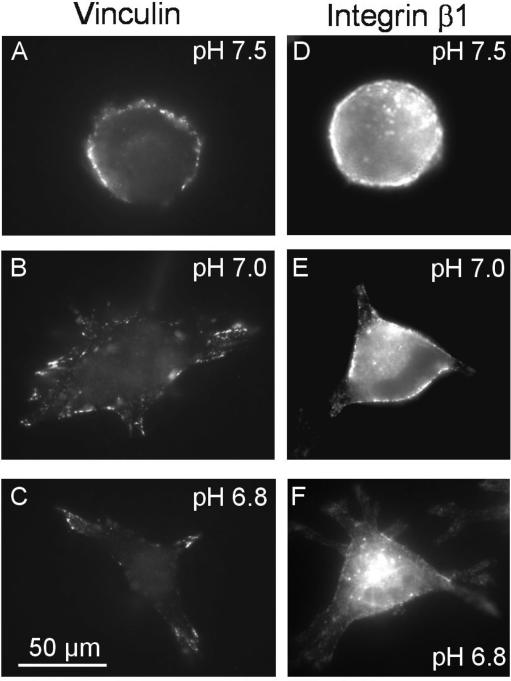

Formation and distribution of focal adhesion sites are affected by pHe

The distribution of vinculin, a cytosolic component of the focal contacts, was also affected by pHe (Fig. 9A–C). Immunolocalization of the plasma membrane-associated vinculin revealed that it was more or less evenly distributed along the plasma membrane of cells exposed to pHe 7.5. At pHe 7.2 and 7.0 the vinculin was still rather evenly distributed but also appeared in a spotty fashion along the lamellipodia. At lower pHe values it accumulated in a typically patchy pattern at the leading edges, i.e. the tips, of the lamellipodia. The distribution of integrin β1 did not fully correspond to that of vinculin. The integrin β1 in lamellipodia of cells exposed to lower pHe at which stronger adhesion had been observed was hardly labelled (Fig. 9F). The incorporation of less integrin β1 into the plasma membrane appears to be an improbable cause for this phenomenon since the expression of integrin β1 does not depend on pHe (Fig. 8) and since the traction forces exerted on the collagen fibres are higher at low pHe (Fig. 7). We favour the explanation that the extracellular binding site for the function blocking antibody might be sterically blocked by collagen and therefore not accessible for the antibody.

Figure 9. Comparison of the distributions of vinculin (A–C) and integrin β1 (D–F) in MV3 cells at different pHe.

Cells were seeded on collagen at different pHe values and then fixed 60 min after seeding. pHe varied between pH 6.8 and pH 7.5. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Discussion

NHE activity plays a key role in cell migration. It is required for the migration of keratinocytes (Bereiter-Hahn & Voth, 1988), human leucocytes (Simchowitz & Cragoe, 1986; Ritter et al. 1998), neutrophil granulocytes (Rosengren et al. 1994), fibroblasts (Denker & Barber, 2002b) and renal epithelial (Madin-Darby canine kidney, MDCK-F) cells (Klein et al. 2000). NHE inhibition leads to a reduction in the migration rate of MDCK-F cells (Klein et al. 2000) while NHE activation augments the motility and the invasiveness of human breast carcinoma cells (Reshkin et al. 2000). The present results are fully consistent with those findings showing a drastic impairment in cell motility of human melanoma cells in response to NHE inhibition by EIPA or HOE642.

Another key finding of the present study is that migration, morphology and adhesion or cell–matrix interactions mediated by integrin α2β1 depend on pHe. Modifying the pHe changed pHi as well. However, pHe-induced modifications of pHi can be ruled out as the only cause for the observed effects. Intracellular acidification was accompanied by either a round morphology and a low adhesion rate in the case of NHE inhibition or by a dendritic morphology and a higher adhesion rate upon exposure to a low pHe. Conversely, cells were spherical regardless of whether pHi was alkaline (in response to exposure to a high pHe) or acidic (because of NHE inhibition). Moreover, cells were dendritic with an almost normal pHi in the presence of sodium propionate, whereas they became spherical with an acidic pHi after additional exposure to HOE642. The question arises what factors other than pHe-induced modifications of pHi may be involved. Needless to say, NHE activity is one candidate. NHE blockage or alkaline pHe and pHi result in low or no NHE activity, which causes the cells to round up. Acidic pHe and pHi or stimulation of the NHE by loading the cells with propionic acid result in high NHE activity leading to a dendritic cell shape and a high adhesiveness. Thus, it is obvious that there is a correlation between the NHE activity of human melanoma cells, their migration, morphology and adhesion. These observations are in line with previous studies showing that (i) a loss of the NHE1-dependent cytsokeletal anchoring impairs cell polarity and reduces the directionality in cell migration (Denker & Barber, 2002b), (ii) the transport activity of the NHE1 is stimulated during cell adhesion (Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz & Lechene, 1992), and (iii) NHE1 activity is necessary for the assembly of focal adhesions (Tominaga & Barber, 1998).

However, the present results provide evidence that pHe itself contributes to the observed effects. The results point to a modulation of the cells' adhesiveness, i.e. to a modulation of the interaction between integrin α2β1 and collagen I by pHe. What is the experimental justification for this explanation? First, exposure of EIPA-treated cells to lower pHe values leads to an increase in the cells' adhesiveness suggesting that the effects of NHE inhibition on cell adhesion can, at least partially, be neutralized by extracellular acidification (Fig. 6). Second, cells pull on the matrix at pHe 6.8 as shown by the displacement of beads incorporated in the matrix whereas they do not displace adjacent beads at pHe 7.5 indicating a rather tight cell surface–matrix interaction at lower pHe values (Fig. 7). This experiment also demonstrates that extracellular acidification in the observed pH range does not reduce the contractility of MV3 cells. This is of interest since an acidic pH can exert effects on cell contractility by altering the structure, activity, or interaction of several actin-binding and cross-linking proteins such as the actin depolymerizing factor (Hawkins et al. 1993; Faff & Nolte, 2000), talin (Schmidt et al. 1993) or α-actinin (Condeelis & Vahey, 1982). Third, the number of lamellipodia in EIPA-treated cells increases as pHe decreases (Fig. 4). It seems that at low pHe values the lamellipodia cannot become detached from the matrix so that the affected cells remain stuck and hardly migrate while forming new processes that again can barely be retracted. Fourth, although a rather soft finding, the present immunofluorescence stainings (Fig. 9) are in line with the previous arguments. Vinculin forming the cytoskeletal link between integrin β1-bound talin and other cytosolic components of focal adhesions such as tensin, paxillin and α-actinin (Zamir & Geiger, 2001) accumulates at the leading edges of lamellipodia at low pHe while it seems to be evenly distributed along the membrane at pHe 7.5. At the same time the access for the integrin β1 mAb to its extracellular epitope is impaired as pHe decreases. This is consistent with the idea that a higher extracellular proton concentration increases the integrin/collagen binding force thereby sterically blocking the mAb's access to its binding site. Fifth, the expression of integrin β1 was not affected by pHe (Fig. 8). Palecek et al. (1997) demonstrated that varying the quantitiy of integrins or its ligands has a strong impact on cell–substratum adhesiveness in CHO cells and thereby affects migration. We cannot completely rule out a pHe-dependent incorporation of integrin β1 into the plasma membrane of MV3 cells. However, the pHe-independent integrin β1-expression implies that besides the quantity of cell matrix interactions their binding strength, probably affected by pHe, may also modify adhesion and migration. Sixth, applying atomic force microscopy Lehenkari & Horton (1999) found the pH optimum for the binding force of the fibronectin ligand-sequence GRGDSP to integrin ανβ3 to be pH 6.5. This is consistent with the present finding that at pHe 6.4 the binding loosens and the cells are of spherical shape. The NHE1 is very active at pHe 6.4, which may decrease the local pHe at the outer face of the plasma membrane to even lower values. When NHE is inhibited by EIPA at pHe 6.4 no more protons are exported from the cytosol to the outer face of the plasma membrane and the local pHe may be less acidic than it would be in the absence of EIPA. Consequently, cells are less spherical in the presence of EIPA.

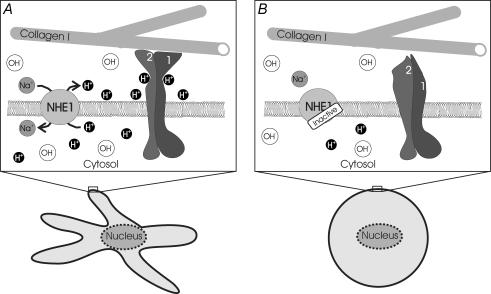

Interestingly, the NHE and the integrin receptor molecules are often colocalized at the focal adhesion sites of the leading edges of lamellipodia (Grinstein et al. 1993; Plopper et al. 1995). Thus, the NHE could create a proton-enriched microenvironment in the immediate vicinity of the focal adhesion complexes, i.e. close to integrin molecules. In fact, protons can be laterally transferred along the surface of biological membranes. They move along lipid/water interfaces rather than diffusing away (Prats et al. 1986; Tessiéet al. 1990). The current state of literature combined with the present observations led us to hypothesize that the local pH at focal adhesion sites may influence the strength of cell adhesion, i.e. of the integrin/collagen bond, and thereby affect cell migration (Fig. 10). A surplus of protons or a lively NHE activity would lead to a tight adhesion whereas alkalosis, a lack of protons or an inhibited NHE activity would prevent adhesion. Future experiments will have to verify this hypothesis and to show the existence of such a pH microenvironment at the outer surface of the plasma membrane.

Figure 10. Hypothetical model of the integrin–collagen interaction.

Integrins and NHE1 are colocalized. Protons stabilize the collagen–integrin (α2β1 dimer) bond. A, acidosis, a surplus of protons or a lively NHE activity, leads to tight adhesion which generates a dendritic cell shape. B, alkalosis, a lack of protons or an inhibited NHE activity, prevents adhesion and cells become spherical.

Integrin binding to the extracellular matrix triggers a multitude of intracellular signals that are in part transmitted by the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and the integrin linked kinase (ILK; Wu & Dedhar, 2001). They bind to integrin β tails (Liu et al. 2000). The phosphorylation state of FAK and its kinase activity are regulated by the binding of cells to the extracellular matrix (Schlaepfer & Hunter, 1998; Hauck et al. 2001; Hauck et al. 2002). On the assumption that extracellular protons stabilize the integrin–collagen bond, it is to be expected that at pHe 7.5 (weak adhesion) no or less FAK is phosphorylated than at pHe 6.6 (strong adhesion). Alternatively, other integrin pathways such as the RACK1–Src interaction (Cox et al. 2003) may be involved. Future studies will show if and how those signal transduction pathways starting from the integrin–collagen interaction are affected by the proton concentration at the cell surface. The binding of collagen to integrin α2β1 is stimulated by Mg2+ and Mn2+ and inhibited by Ca2+ (Humphries, 2002). We are now trying to imitate the effects pHe has on cell adhesion, migration and morphology by (i) varying the Mg2+/Ca2+ ratio in the experimental solution and (ii) adding Mn2+.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Peter Friedl's laboratory (Rudolf-Virchow-Zentrum, Universität Würzburg) for teaching us how to create 3D collagen lattices and Dr Claudia Eder for fruitful discussions. J.A.E. receives a grant from the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (grant number: 2003.136.1). This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant number: 407/9/1).

Supplemental material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088344 http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2005.088344/DC1

References

- Beningo KA, Dembo M, Kaverina I, Small JV, Wang Y-L. Nascent focal adhesions are responsible for the generation of strong propulsive forces in migrating fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:881–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereiter-Hahn J, Voth M. Ionic control of locomotion and shape of epithelial cells. II. Role of monovalent cations. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1988;10:528–536. doi: 10.1002/cm.970100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF. Transport of H+ and ionic weak acids and bases. J Membr Biol. 1983;72:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01870311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, Fässler R. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. EMBO J. 2003;22:2324–2333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J, Vahey M. A calcium- and pH-regulated protein from Dictyostelium discoideum that cross-links actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:466–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EA, Bennin D, Doan AT, O'Toole T, Huttenlocher A. RACK1 regulates integrin-mediated adhesion, protrusion, and chemotactic cell migration via its Src-binding site. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:658–669. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker SP, Barber DL. Ion transport proteins anchor and regulate the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002a;14:214–220. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker SP, Barber DL. Cell migration requires both ion translocation and cytoskeletal anchoring by the Na-H exchanger NHE1. J Cell Biol. 2002b;159:1087–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker SP, Huang DC, Orlowski J, Furthmayr H, Barber DL. Direct binding of the Na-H exchanger NHE1 to ERM proteins regulates the cortical cytoskeleton and cell shape independently of H+-translocation. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1425–1436. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GA, Brown AF. A unified approach to analyzing cell motility. J Cell Scisupplement. 1987;8:81–102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1987.supplement_8.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GA, Brown AF. Quantifying cellular shape using moment invariants. Lecture Notes Biomathematics, Biol Motion. 1990;89:10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Eble JA, Tuckwell DS. The α2β1 integrin inhibitor rhodocetin binds to the A-domain of the integrin α2 subunit proximal to the collagen-binding site. Biochem J. 2003;376:77–85. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nature Rev. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faff L, Nolte C. Extracellular acidification decreases the basal motility of cultured mouse microglia via the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. Brain Res. 2000;853:22–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire E, Coelho-Sampaio T. Self-assembly of laminin induced by acidic pH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:817–822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Bröcker E-B. The biology of cell locomotion within three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:41–64. doi: 10.1007/s000180050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nature Rev. 2003;3:362–374. doi: 10.1038/nrc1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Zänker KS, Bröcker E-B. Cell migration strategies in 3-D extracellular matrix: differences in morphology, cell matrix interactions, and integrin function. Microsc Res Techn. 1998;43:369–378. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981201)43:5<369::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander DR, Zagzag D, Shiff B, Cohen H, Allen JC, Kelly PJ, Grumet M. Migration of brain tumor cells on extracellular matrix proteins in vitro correlates with tumor type and grade and involves alphaV and beta1 integrins. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1939–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JR. Are cancer cells acidic? Br J Cancer. 1991;64:425–427. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinstein S, Woodside M, Waddell TK, Downey GP, Orlowski J, Pouyssegur J, Wong DCP, Foskett JK. Focal localization of the NHE-1 isoform of the Na+/H+ antiport: assessment of effects on intracellular pH. EMBO J. 1993;12:5209–5218. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulledge CJ, Dewhirst MW. Tumor oxygenation: a matter of supply and demand. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:741–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck CR, Hsia DA, Ilic D, Schlaepfer DD. v-SRC SH3-enhanced interaction with focal adhesion kinase at β1 integrin-containing invadopodia promotes cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12487–12490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck CR, Sieg DJ, Hsia DA, Loftus JC, Gaarde WA, Monia BP, Schlaepfer DD. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase expression or activity disrupts epidermal growth factor-stimulated signaling promoting the migration of invasive human carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7079–7090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins M, Pope B, Maciver SK, Weeds AG. Human actin depolymerizing factor mediates a pH-sensitive destruction of actin filaments. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9985–9993. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmlinger G, Sckell A, Dellian M, Forbes NS, Jain RK. Acid production in glycolysis-impaired tumors provides new insights into tumor metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1284–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MJ. Insights into integrin-ligand binding and activation from the first crystal structure. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:S69–S78. doi: 10.1186/ar563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalali S, del Pozo MA, Chen K-D, Miao H, Li Y-S, Schwartz MA, Shy J-Y, Chien S. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction requires its dynamic interaction with specific extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1042–1046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031562998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Seeger P, Schuricht B, Alper SL, Schwab A. Polarization of Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− exchangers in migrating renal epithelial cells. J General Physiol. 2000;115:599–607. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde AE, Franchis AJ, Paris S, Poyssegur JM. Effect of mutations affecting Na+: H+ antiport activity on tumorigenic potential of hamster lung fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 1988;36:249–260. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehenkari PP, Horton MA. Single integrin molecule adhesion forces in intact cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:645–650. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3536–3571. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaser K, Wolf K, Klein CE, Niggemann B, Zänker KS, Bröcker E-B, Friedl P. Functional hierarchy of simultaneously expressed adhesion receptors: integrin α2β1 but not CD44 mediates MV3 melanoma cell migration and matrix reorganization within three-dimensional hyaluron-containing collagen matrices. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3067–3079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean LA, Roscoe J, Jørgensen NK, Gorin FA, Cala PM. Malignant gliomas display altered pH regulation by NHE1 compared with nontransformed astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C676–C688. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison TJ, Cramer LP. Actin-based cell motility and cell locomotion. Cell. 1996;84:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek SP, Loftus JC, Ginsberg MH, Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Integrin-ligand binding properties govern cell migration speed through cell substratum adhesiveness. Nature. 1997;385:537–540. doi: 10.1038/385537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plopper GE, McNamee HP, Dike LE, Bojanowski K, Ingber DE. Convergence of integrin and growth factor receptor signaling pathways within the focal adhesion complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1349–1365. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prats M, Teissié J, Tocanne J-F. Lateral proton conduction at lipid–water interfaces and its implications for the chemiosmotic-coupling hypothesis. Nature. 1986;322:756–758. [Google Scholar]

- Reshkin SJ, Bellizzi A, Albarini V, Guerra L, Tommasino M, Paradiso A, Casavola V. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase is involved in the tumor-specific activation of human breast cancer cell Na+/H+ exchange, motility, and invasion induced by serum deprivation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5361–5369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter M, Schratzberger P, Rossmann H, Wöll E, Seiler K, Seidler U, Reinisch U, Kahler CM, Zwierzina H, Lang HJ, Lang F, Wiedermann CJ. Effect of inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchange and gastric H+/K+ ATPase on cell volume, intracellular pH and migration of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:627–638. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren S, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Migration-associated volume changes in neutrophils facilitate the migratory process in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1623–C1632. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotin D, Steele-Norwood D, Grinstein S, Tannock IF. Requirement of the Na+/H+ exchanger for tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1989;49:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Hara-Chikuma M, Verkman AS. Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption. Nature. 2005;434:786–792. doi: 10.1038/nature03460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T. Integrin signalling and tyrosine phosphorylation: just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JM, Robson RM, Zhang J, Stromer MH. The marked pH-dependence of the talin–actin interaction. Biochim Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:660–666. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz W, Albus U, Counillon L, Gogelein H, Lang HJ, Linz W, Weichert A, Scholkens BA. Protective effects of HOE642, a selective sodium-hydrogen exchange subtype 1 inhibitor, on cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab A. Function and spatial distribution of ion channels and transporters in cell migration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F739–F747. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.5.F739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwark JR, Jansen HW, Lang HJ, Krick W, Burckhardt G, Hropot M. S3226, a novel inhibitor of Na+/H+ exchanger subtype 3 in various cell types. Eur J Physiol. 1998;436:797–800. doi: 10.1007/s004240050704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA. Transmembrane signalling by integrins. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:304–308. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90120-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Lechene C. Adhesion is required for protein kinase C-dependent activation of the Na+/H+ antiporter by platelet-derived growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6138–6141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Lechene C, Ingber DE. Insoluble fibronectin activates the Na/H antiporter by clustering and immobilizing integrin α5β1, independent of cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7849–7853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simchowitz L, Cragoe EJ. Regulation of human neutrophil chemotaxis by intracellular pH. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6492–6500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamariz E, Grinnell F. Modulation of fibroblast morphology and adhesion during collagen matrix remodeling. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3915–3929. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock IF, Rotin D. Acid pH in tumors and its potential for therapeutic exploitation. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4373–4384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessié J, Prats M, LeMassu A, Stewart LC, Kates M. Lateral proton conduction in monolayers of phospholipids from extreme halophiles. Biochemistry. 1990;29:59–65. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga T, Barber DL. Na-H exchange acts downstream of RhoA to regulate integrin-induced cell adhesion and spreading. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2287–2303. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Muijen GN, Jansen KF, Cornelissen IM, Smeets DF, Beck JL, Ruiter DJ. Establishment and characterization of a human melanoma cell line (MV3) which is highly metastatic in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1991;48:85–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl ML, Pooler PM, Briand P, Leeper DB, Owen CS. Intracellular pH regulation in a nonmalignant and a derived malignant human breast cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2002;183:373–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200006)183:3<373::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb DJ, Parsons JT, Horwitz AF. Adhesion assembly, disassembly and turnover in migrating cells – over and over and over again. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E97–E100. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR, Gelman RA, Poppke DC, Piez KA. Collagen fibril formation. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6578–6585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Dedhar S. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and its interactors: a new paradigm for the coupling of extracellular matrix to actin cytoskeleton and signaling complexes. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:505–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata M, Tannock IF. The chronic administration of drugs that inhibit the regulation of intracellular pH: in vitro and anti-tumour effects. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1328–1334. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir E, Geiger B. Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3583–3590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.