Abstract

Cyclic AMP regulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis through a classical protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent and an alternative cAMP–guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)/Epac-dependent pathway in many secretory cells. Although increased cAMP is believed to double secretory output in isolated pituitary cells, the direct target(s) for cAMP action and a detailed and high-time resolved analysis of the effect of intracellular cAMP levels on the secretory activity in melanotrophs are still lacking. We investigated the effect of 200 μm cAMP on the kinetics of secretory vesicle depletion in mouse melanotrophs from fresh pituitary tissue slices. The whole-cell patch-clamp technique was used to depolarize melanotrophs and increase the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). Exogenous cAMP elicited an about twofold increase in cumulative membrane capacitance change and ∼34% increase of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channel amplitude. cAMP-dependent mechanisms did not affect [Ca2+]i, since the application of forskolin failed to change [Ca2+]i in melanotrophs, a phenomenon readily observed in anterior lobe. Depolarization-induced secretion resulted in two distinct kinetic components: a linear and a threshold component, both stimulated by cAMP. The linear component (ATP-independent) probably represented the exocytosis of the release-ready vesicles, whereas the threshold component was assigned to the exocytosis of secretory vesicles that required ATP-dependent reaction(s) and > 800 nm[Ca2+]i. The linear component was modulated by 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (Epac agonist), while either H-89 (PKA inhibitor) or Rp-cAMPS (the competitive antagonist of cAMP binding to PKA) completely prevented the action of cAMP on the threshold component. In line with this, 6-Phe-cAMP, (PKA agonist), increased the threshold component. From our study, we suggest that the stimulation of cAMP production by application of oestrogen, as found in pregnant mice, increases the efficacy of the hormonal output through both PKA and cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent mechanisms.

In synaptic terminals and specialized endocrine cells, a brief depolarization activates voltage-activated Ca2+ channels (VACCs). In so-called Ca2+ microdomains around the inner mouth of an open calcium channel, calcium is believed to increase to several tens or even hundreds of micromoles (Neher, 1998). Secretory vesicles within such a microdomain can fuse immediately with the plasma membrane (the immediately releasable pool, IRP) (Horrigan & Bookman, 1994), while the rate of fusion for the secretory vesicles outside the Ca2+ microdomain is several orders of magnitude lower (Voets et al. 1999; Sorensen, 2004).

Melanotrophs, neuroendocrine cells from the intermediate lobe of the pituitary, secrete α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and β-endorphin in response to electrical activity (Mains & Eipper, 1979). Both peptide hormones are stored in several tens of thousands of vesicles, of which only ∼5% dwell in close apposition to the plasmalemma and are referred to as morphologically docked (Parsons et al. 1995). In isolated rat melanotrophs, a rapid and homogeneous release of caged Ca2+ by flash photolysis is able to deplete all these docked vesicles in an ATP-independent manner (Thomas et al. 1993a; Parsons et al. 1995; Rupnik et al. 2000). Short depolarization trains (lasting up to 10 s), on the other hand, trigger a release of a much smaller number of release-ready vesicles (Thomas et al. 1990; Mansvelder & Kits, 1998; Sedej et al. 2004) and allow secretory vesicles fusing near the open calcium channels to be separated from those outside Ca2+ microdomains, particularly when an endocrine slice preparation is used (Moser & Neher, 1997b).

In addition to a direct modulation by VACCs, stimulus–secretion coupling is controlled by multiple downstream intracellular messengers that further regulate secretion in neuroendocrine cells (Okano et al. 1993; Gillis et al. 1996; Sikdar et al. 1998). In particular cAMP, which is generally believed to act by activating protein kinase A (PKA), is able to enhance exocytosis in synapses (Chavez-Noriega & Stevens, 1994), chromaffin cells (Morgan et al. 1993; Carabelli et al. 2003), pancreatic β-cells (Ämmäläet al. 1993; Eliasson et al. 2003; Wan et al. 2004) and pituitary cells (Lee, 1996; Sikdar et al. 1998). Recently, another cAMP-dependent, but PKA-independent, mechanism has been suggested to explain an alternative mechanism of cAMP action on the Ca2+-dependent exocytosis involving cAMP–guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), also known as Epacs (Epac1 and Epac2) (Kawasaki et al. 1998; de Rooij et al. 2000; Ozaki et al. 2000; Eliasson et al. 2003; Zhong & Zucker, 2005). The expression of cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 mRNA has been reported in mouse anterior pituitary (Ozaki et al. 2000) and melanotrophs (T. Iwanaga & S. Seino, personal communication).

The effect of cAMP in isolated rat melanotrophs is measured under conditions in which there is an increase in [Ca2+]i and the process is maximally activated in the range between 450 nm (Sikdar et al. 1998) and 3 μm (Lee, 1996). The increase in secretory activity by cAMP through PKA has been associated with the increase in the size of unitary exocytotic events (Sikdar et al. 1998). However, a detailed and high time-resolved analysis of the effect of elevated intracellular cAMP levels on the kinetics of secretory vesicle pool depletion in melanotrophs has not been performed so far. A possible reason might be the reduced sensitivity of fusion apparatus during the cell isolation and culturing process as shown also in chromaffin cells (Moser & Neher, 1997b). Hence, we used the advantages offered by pituitary slice preparation to assess the role of cAMP in Ca2+-dependent secretory activity.

The effect of cAMP on exocytosis may account for the physiological regulation of exocytotic peptide hormone output from adult melanotrophs. Under non-stimulated conditions, the majority of melanotrophs are under tonic dopaminergic inhibition (Millington & Chronwall, 1989). Acute stimulation of dopamine D2 receptors, for seconds or minutes, reduces the cytosolic level of cAMP via a reduction of adenylyl cyclase activity (Munemura et al. 1980; Frey et al. 1982). Tonic inhibition due to dopaminergic innervation and activation of D2 receptors keeps cAMP levels low (Frey et al. 1982). This innervation is absent at birth (Gomora et al. 1996) and is further antagonized by oestrogen signalling (Dufy et al. 1979). We showed, in our previous work, that increased secretory activity in melanotrophs from newborn and pregnant mice is attributed to the elevated physiological levels of oestrogen (Sedej et al. 2004). Exactly which signal transduction pathway explains how 17β-oestradiol triggers hormone secretion has been unclear. We hypothesized that 17β-oestradiol activates adenylyl cyclase and increases the cAMP levels as found in chromaffin cells (Machado et al. 2002) and uterine cells (Aronica et al. 1994). Therefore, it is likely that in adult melanotrophs, oestrogen may antagonize dopamine through cAMP-dependent mechanism(s) during the physiological states that demand glandular hyperactivity, e.g. during pregnancy.

Here, we show that mouse melanotrophs from tissue slices displayed a clear separation between the fusion of release-ready vesicles within the Ca2+ microdomain (∼15 vesicles) from the release of secretory vesicles outside the microdomain (the linear component). In addition, during prolonged stimulation the cytosolic [Ca2+]i reached a threshold (> 800 nm) and triggered exocytosis of another set of the secretory vesicles (the threshold component) that required ATP-dependent reactions (e.g. priming). Both exocytotic components were sensitive to cAMP. As in several other neuroendocrine systems, both PKA-dependent (threshold component) and cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent (linear component) pathways selectively controlled the Ca2+-dependent secretory activity at resting and elevated cAMP levels, respectively. The present work suggests a physiological implication of elevated cAMP in increased secretory activity in pituitary cells from pregnant female mice governed both PKA- and cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent mechanism.

Methods

Pituitary slice preparation

NMRI mice (adult male, 6–10 weeks old; pregnant female, day 19 and newborn: P1–P2) were killed by exposure to a CO2 atmosphere and decapitated. Animal work was performed according to the regulations of the State of Lower Saxony, Germany. Acute pituitary slices, 80 μm thick, were prepared as previously described (Sedej et al. 2004). Briefly, the pituitary was carefully removed from the skull and rinsed with ice-cold external solution 1 composed of (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, sodium pyruvate 2, myo-inositol 3, ascorbic acid 0.5, glucose 10, NaHCO3 26, MgCl2 3, CaCl2 0.1, lactic acid 6. The gland was then embedded in 2.5% low melting agarose (Seaplaque GTG agarose, BMA, Walkersville, MD, USA), glued on the sample plate of a vibrotome VT1000S (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and sectioned in ice-cold external solution 2 (mm): KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, sodium pyruvate 2, myo-inositol 3, ascorbic acid 0.5, sucrose 250, glucose 10, NaHCO3 26, MgCl2 3, CaCl2 0.1, lactic acid 6. Fresh slices were then transferred to an incubation beaker containing oxygenated external solution 1 and kept at 32°C for up to 8 h.

For the slice culture, pituitary slices from adult male mice were transferred onto the culture plate mesh (Millicell-CM, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and inserted into the 6-well plate (Cellstar, Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmuenster, Austria). Slices were kept in an incubator at 37°C, in 95% humidity and 5% CO2 in phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with nutrient mix F-12 (DMEM/F-12; Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA; 100 U penicillin and 100 μg streptomycin ml−1 medium; pH 7.2) for 24 h before the experimentation. Phenol red-free medium was used due to the weak oestrogenic effect of phenol red in the anterior pituitary cells (Hofland et al. 1987). 17β-Oestradiol was prepared as a 3.7 mm stock solution in ethanol. The final ethanol concentration in the medium was less than 0.0001%, thus having no effect on the Ca2+ current density (Ritchie, 1993). To test the effect of oestrogen, 1 nm 17β-oestradiol was added to the culturing medium. The control slices for the 17β-oestradiol treated slices were also cultured for 24 h. This set of experiments was performed in the external solution 3 with 5 mm CaCl2 (see below).

Measurement of intracellular cAMP content in the melanotrophs

After decapitation and pituitary removal (see above), neurointermediate lobes (NIL) were separated from anterior pituitary with Dumont forceps (Fine Science Tools Inc., Vancouver, Canada) under the Olympus SZX9 stereomicroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). NILs were left enzymatically and mechanically intact in order to reduce the stress and assure precise [cAMP]i measurements of the preparation. The cAMP content was determined with a cAMP Biotrak enzyme immunoassay kit using non-acetylation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) procedure (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Electrophysiology

Changes in cell membrane capacitance (ΔCm) and Ca2+ currents were measured in single melanotrophs within intact clusters of the intermediate lobe of the pituitary gland by using the conventional whole-cell patch-clamp configuration (Neher & Marty, 1982). In our conditions the intermediate lobe could easily be recognized as a narrow band of tissue engulfing the neuropituitary (Schneggenburger & Lopez-Barneo, 1992; Sedej et al. 2004; see online Supplemental material, Fig. 9). The vast majority of intermediate lobe cells are melanotrophs (Turner et al. 2005). During the measurements, the slice was perfused continuously (1–2 ml min−1) with external solution 3 composed of (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, sodium pyruvate 2, myo-inositol 3, ascorbic acid 0.5, glucose 10, NaHCO3 26, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 2, lactic acid 6. The osmolality of extracellular solutions 1 and 3 and intracellular solution was 300 ± 10 mosmol kg−1, whereas external solution 2 was hypertonic with 360 ± 10 mosmol kg−1. External solutions 1, 2 and 3 were continuously bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to keep the pH stable at 7.3.

The intracellular solution was (mm): CsCl 140, Hepes 10, MgCl2 2, TEA-Cl 20, Na2ATP 2, EGTA 0.05. Na2ATP was omitted in Fig. 1B. Cyclic AMP and ATP were prepared as stock solutions and diluted in the pipette solution before the pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The PKA inhibitor H-89 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) was dissolved in DMSO and added to the external solution 3 prior to the experiments to reach a final concentration of 1 μm; pituitary slices were perfused for at least 10 min with H-89 before recording. The final DMSO concentration in the external solution was less than 0.01%. The competitive antagonist of cAMP binding to PKA, Rp-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic-monophosphorothioate triethylammonium salt (Rp-cAMPS; Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany) and PKA agonist, 6-Phe-cAMP (Biolog) were included in the pipette solution at concentrations of 0.5 mm and 0.1 mm, respectively. A selective cAMP–GEF/Epac agonist, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP; Biolog), was used at concentration of 0.1 mm. At least 5 min were allowed for a full dialysis (Eliasson et al. 2003) and ATP washout (Parsons et al. 1995). All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated.

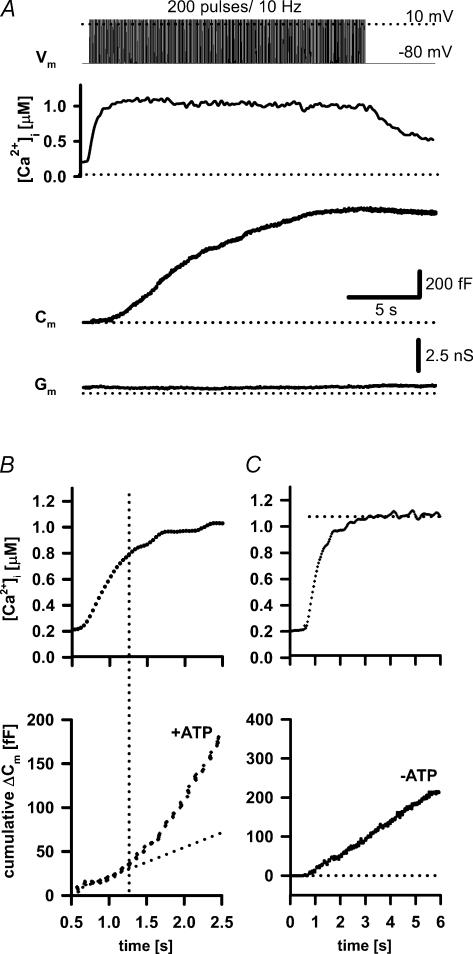

Figure 1. Ca2+-dependent exocytosis evoked by a depolarization protocol in control melanotrophs.

A, the secretory response was triggered by a train of 200 pulses (40 ms duration, at 10 Hz). These depolarizations were associated with a step-like elevation in [Ca2+]i and an increase in membrane capacitance (Cm). Note that membrane conductance (Gm) remained unchanged throughout the stimulation. B, cumulative Cm in the presence of ATP (lower panel). Note the threshold (dashed line) that separates a linear component (ATP-independent) from threshold component (ATP-dependent). C, depolarization-induced secretory response after the washout of ATP (9 min of dialysis in the absence of the ATP in the pipette) was linear (lower panel).

Cells were visualized with an upright Nikon Eclipse E600 FN microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a mounted CCD camera (Cohu, San Diego, CA, USA). Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) using a P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and heat polished to obtain a resistance of 2–4 MΩ in CsCl-based solution. Whole-cell currents and capacitance changes were measured with a lock-in patch-clamp amplifier (SWAM IIC, Celica, Ljubljana, Slovenia), low-pass filtered (3 kHz, −3 dB) and stored on a standard PC. The cells were voltage clamped at −80 mV. Ca2+ currents were leak corrected. Cells that showed less than −30 pA peak amplitude Ca2+ current (∼10%) were discarded from the analysis. For pulse generation, data acquisition and basic analysis, we used WinWCP V3.3.9. software from J. Dempster (Strathclyde University, Glasgow). High-resolution capacitance measurements (in the femtofarad range) were made by using the compensated technique as previously described (Zorec et al. 1991), using a sinusoidal voltage (1600 Hz, 10 mV peak-to-peak). To determine ΔCm values, membrane capacitance was first averaged over 30 ms preceding the depolarization to obtain a baseline value, which was subtracted from the value estimated after the depolarization averaged over a 40 ms window. The first 30 ms after the depolarization was excluded from the Cm measurement to avoid contamination by non-secretory capacitative transients related to gating charge movement (Horrigan & Bookman, 1994). The use of tetrodotoxin was avoided because it prolongs a transient non-secretory capacitance change (Horrigan & Bookman, 1993).

All electrophysiological experiments were performed at 30–32°C. Control experiments (no cAMP in the patch pipette) were performed on adult male melanotrophs, unless otherwise noted. Signal processing and curve fitting was done using SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA) and Matlab (Mathworks, Novi, MI, USA). Data and results are reported as mean ±s.e.m. for the indicated number of experiments. Estimates of the number of vesicles released are based on a value of 1 fF per vesicle for adult melanotrophs (Thomas et al. 1993b). Differences between samples were tested using Student's paired t test, one-way ANOVA (by Tuckey's post hoc follow up test) and one-way ANOVA on Ranks (by Dunn's test, SigmaStat, Systat Software Inc.). The significance level was chosen at P < 0.05.

Ca2+ measurements

Fura-PE3 (TEF Laboratories, USA; 50 μm added to the pipette solution) was used to monitor intracellular Ca2+-concentration ([ΔCa2+]i) changes simultaneously with the patch-clamp recordings. Cells loaded with fura-PE3 remain brightly loaded and lack fluorescent dye compartmentalization for hours (Vorndran et al. 1995). Monochromatic light (Polychrome IV; TILL Photonics, Germany) alternating between 340 and 380 nm (50 Hz) was short-pass filtered (at 410 nm) and reflected by a dichroic mirror (centred at 400 nm) to the perfusion chamber. The emitted fluorescence was transmitted by the dichroic mirror and further filtered through a 470 nm barrier filter. Images were obtained using a cooled emCCD camera (Ixon, Andor Technology, Japan) and native Andor software. [ΔCa2+]i was calculated from the intensity ratios of the background subtracted images obtained with 340 and 380 nm excitation light according to established methods (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985) as:

where Kd is the dissociation constant (264 nm), β is the fluorescence ratio of free/bound fura-PE3 measured with 380 nm excitation, R is the experimentally derived fluorescence ratio, and Rmin and Rmax are ratios measured using calibration solutions containing no Ca2+ or saturating Ca2+, respectively; these were determined from in vivo calibrations. The mean values (n = 3) of Rmin, Rmax and β were 0.15, 1.17 and 6.45, respectively. Image processing and calculations were performed by a custom Matlab script.

Results

The effect of cAMP on Ca2+-dependent secretory activity

Under control conditions, a prolonged stimulation (200 depolarization pulses from −80 mV to 10 mV at 10 Hz, 40 ms duration) elicited a sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1A). The capacitance increase was significant during the initial 100 pulses, but the rate of the capacitance increase progressively declined towards the end of the depolarizing train (Figs 1A and 2A; Parsons et al. 1995). The reduced rate of capacitance increase may reflect a balance between exo- and endocytosis in the cell. However, the latter is unlikely as no significant endocytotic activity was detected after the end of the train (Fig. 1A; Turner et al. 2005). After the train ceased, intracellular calcium decreased within a few seconds to the resting level of 197 ± 23 nm (n = 18). A sustained train of depolarizing pulses did not produce significant changes in membrane conductance (Gm).

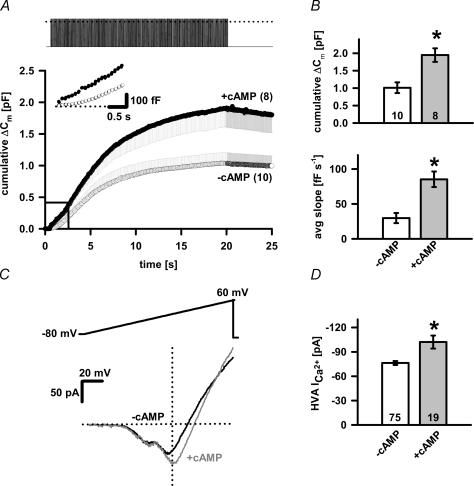

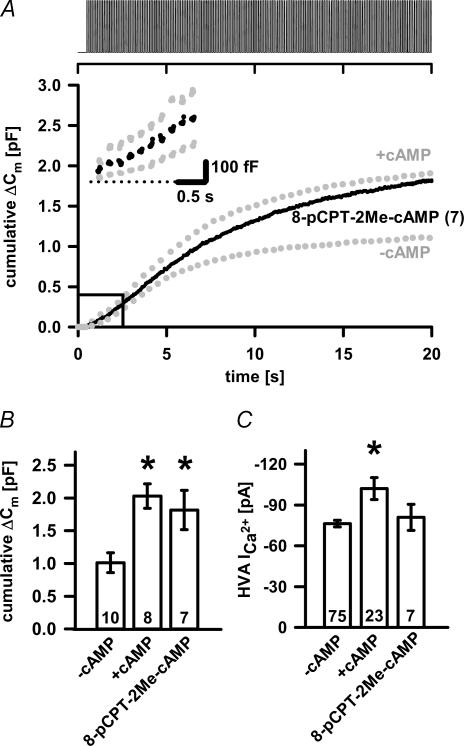

Figure 2. The effect of cAMP on Ca2+-dependent exocytosis and peak VACC amplitude.

A, the secretory response in melanotrophs was measured as a cumulative membrane capacitance change (ΔCm), while the train depolarization of 200 pulses was delivered as in Fig. 1 (upper panel) with or without cAMP in the pipette solution. In control (cAMP non-treated) and cAMP-treated cells, the ΔCm traces are shown as mean and plus s.e.m. data points and mean and minus s.e.m. data points for each pulse, respectively (lower panel). The numbers of cells tested are given in parentheses. The inset shows the first few seconds of capacitance change. B, cAMP significantly increased the cumulative ΔCm after 200 pulses compared to control cells (upper panel; P < 0.001) and the average slope of linear component (lower panel; P < 0.001). C, representative traces of whole-cell Ca2+ currents evoked by 300 ms voltage ramps from −80 mV to +60 mV without (black) and with 200 μm cAMP (grey) in the pipette solution. Note the difference in the peak high-voltage-activated Ca2+ current amplitude, while the peak low-voltage-activated Ca2+ current amplitude remained unaffected. D, bar graph of the peak high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ current amplitude from control cells significantly differed from cAMP-treated cells (P < 0.006). Numbers on bars or in parentheses indicate the number of cells tested. Asterisks indicate statistical significance.

A detailed analysis of the cytosolic Ca2+ and capacitance increase during the depolarization train revealed two separate kinetic exocytotic components (Fig. 1B and C). The gradual change in the cytosolic Ca2+ during the first depolarizing pulses can be taken as an equivalent of a Ca2+ ramp elicited by the slow caged Ca2+ release (Fig. 1B, top trace; Zhu et al. 2002). The Ca2+ ramp induced a linear increase (average slope: 39 ± 11 fF s−1; n = 4) in membrane capacitance followed by an additional exocytotic component at > 800 nm[Ca2+]i (threshold level; Fig. 1B). The initial linear component probably represented the exocytosis of the release-ready vesicles as they fused in the ATP-independent manner (Fig. 1C). The linearity of this process is not surprising since the global Ca2+ changes in the cytosol did not vary significantly during the train of pulses (Fig. 1C, top trace, dotted line). A linear response in the capacitance to a step-wise increase in [Ca2+]i to > 10 μm was previously observed in rat melanotrophs using flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ as a CAPS-independent secretory activity (Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion; Rupnik et al. 2000); average slope at 15 μm was > 1000 fF s−1).

To assess how cAMP affects the Ca2+-dependent secretory activity in mouse melanotrophs, the experiment was performed with 200 μm cAMP in the pipette solution (Fig. 2A). Depolarization-evoked secretory responses were measured as the cumulative increase in membrane capacitance 3 min after the start of dialysis. In the presence of cAMP, the total cumulative capacitance response at the end of the stimulus train was significantly higher (1.947 ± 0.194 pF, n = 8; P < 0.001, Fig. 2A and B) in comparison to the control (1.012 ± 0.153 pF; n = 10). In fact, a significant augmentation in capacitance increase in cAMP-dialysed cells was observed throughout the duration of the train (Fig. 2A). Both the linear and threshold component were increased (Fig. 2A and B). The linear component significantly increased in cAMP-treated cells. The average slope of the linear component was 131 ± 17 fF s−1 (n = 5) in cAMP-treated cells and 45 ± 11 fF s−1 (n = 11, P < 0.001) in control cells (Fig. 2A, inset).

The cumulative capacitance change in melanotrophs within the first 50 depolarizations is linearly proportional to the cumulative Ca2+ charge entry (Mansvelder & Kits, 1998; Sedej et al. 2004) and thus the observed augmentation of the exocytotic activity could be the result of an increased Ca2+ current amplitude. Alternatively, cAMP could act downstream of VACCs and directly affect the exocytotic machinery or mobilize [Ca2+]i from internal stores. We found that cAMP significantly increased peak of high VACC amplitude from 76.3 ± 2.4 pA (n = 75) in control cells to 102.1 ± 8.1 pA (n = 19; P < 0.006) in cAMP-treated cells (Fig. 2C and D). The stimulation of secretory output by cAMP (∼100%) cannot be solely attributed to the increased Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space (∼34%).

Ca2+ mobilizing action of forskolin in mouse pituitary

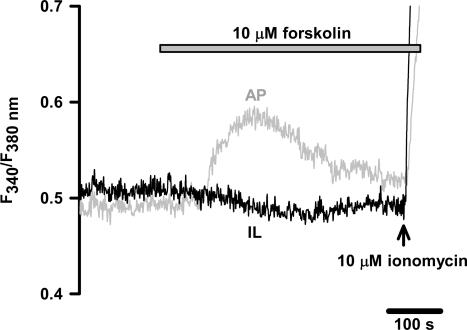

To address whether cAMP has additional Ca2+ mobilizing action in the intact melanotrophs, pituitary slices were stimulated with 10 μm forskolin, an adenylyl cyclase activator, while changes in fluorescence were monitored using Ca2+ indicator, fura PE-3 AM. As shown in Fig. 3, addition of forskolin caused no change in [Ca2+]i in melanotrophs. In contrast, anterior pituitary cells responded with a sustained increase in fluorescence ratio, an indicator of [Ca2+]i changes (see also Supplemental material Fig. 10 and Movie 1). The delay between application and the effect of forskolin was partially due to the time required for forskolin to reach the final concentration in the deeper layers of the tissue slice and initiate the production of cAMP, which released Ca2+ from the internal stores. No change in Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (Turner et al. 2005) associated with cAMP treatment was observed (not shown). Since the increase of the Ca2+-dependent secretory activity could not be exclusively attributed to the increased density of VACCs, we wanted to examine the direct effect of cAMP on the secretory machinery.

Figure 3. Time course of the effect of forskolin on [Ca2+]i in mouse melanotrophs.

The application of 10 μm forskolin (grey bar) resulted in an increased fluorescence ratio (F340nm/F380nm) in anterior pituitary (AP, grey trace), but not in intermediate lobe (IL, black trace; see also Supplemental material Figs 9 and 10 and Movie 1) in three separate experiments. Prior the end of experiment, 10 μm ionomycin (arrow) was added to the bath solution to raise the [Ca2+]i to several micromolar.

PKA-dependent versus cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent secretory activity

So far, only the PKA-dependent pathway has been reported in melanotrophs to contribute to cAMP-dependent stimulation of the secretory activity (Lee, 1996; Sikdar et al. 1998). Recently an abundant expression of cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 mRNA in the mouse anterior pituitary (Ozaki et al. 2000) and also in the intermediate lobe (T. Iwanaga & S. Seino, personal communication) has been shown, suggesting an alternative cAMP mechanism.

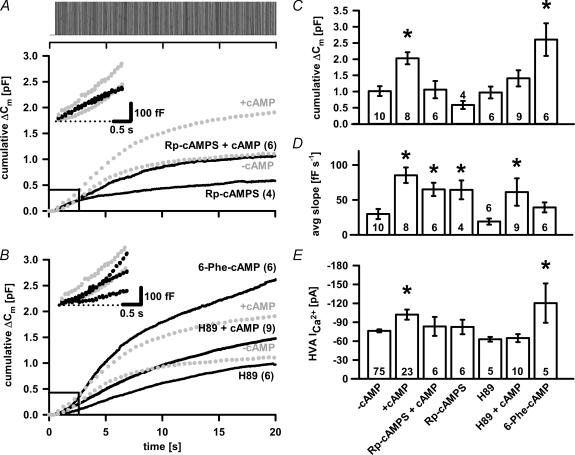

Rp-cAMPS (0.5 mm), a competitive antagonist of cAMP binding to PKA, significantly but not completely reduced cumulative ΔCm (P < 0.04; n = 5), despite unchanged peak VACCs amplitude compared to control melanotrophs (Fig. 4A, C and E). Simultaneous dialysis of 0.5 mm Rp-cAMPS and 200 μm cAMP elicited comparable cumulative ΔCm (1.060 ± 0.266 pF; n = 6) and peak high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ current (−71.7 ± 19.2 pA, n = 6) as in control cells (Fig. 4A, C and E), suggesting that PKA was responsible for the cAMP effect. Surprisingly, the treatment with Rp-cAMPS always produced an increase in the slope of the linear component (99 ± 20 fF s−1, n = 4; Fig. 4A inset and D), which did not differ from the coapplication of Rp-cAMPS/cAMP (100 ± 14 fF s−1, n = 6; Fig. 4A inset and D). Recently (Rehmann et al. 2003) showed that Rp-cAMPS is also able to block human cAMP–GEFI/Epac1, while the effect on cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 still remains to be elucidated. Thus, to ascertain whether the action of Rp-cAMPS is identical to inhibitors of PKA catalytic activity, we applied H-89. As shown in Fig. 4B, H-89 together with cAMP significantly abolished the cAMP effect, indicating the presence of PKA-dependent pathway. The cumulative capacitance response under these conditions was 1.408 ± 0.25 pF (n = 9). While the evoked cumulative capacitance change from cells treated with H-89 alone was comparable with secretory response from control cells (0.97 ± 0.184 pF; n = 6), the time profile of triggered Ca2+-dependent exocytosis between the two groups differed, as only linear component appeared to be present in the H-89-treated cells (29 ± 6 fF s−1, n = 6; Fig. 4B inset and D). The application of both H-89 and cAMP significantly increased the average slope of the linear component (94 ± 29 fF s−1, n = 9; P < 0.02; Fig. 4B inset and D). The application of 6-Phe-cAMP, PKA type I and II agonist, resulted in an increased secretion (2.606 ± 0.505 pF; n = 6; Fig. 4B and C) that, though not significantly, overshot the cAMP response and significantly increased the amplitude of HVA Ca2+ currents (−120.3 ± 31.3 pA; n = 5; P < 0.05, Fig. 4E). The linear component did not significantly differ from control cells after application of 6-Phe-cAMP (60 ± 11 fF s−1, n = 6; Fig. 4B inset and D).

Figure 4. Inhibition of PKA-dependent pathway in melanotrophs.

A, inclusion of Rp-cAMPS did not fully abolish the Ca2+-dependent secretion. On the other hand, simultaneous dialysis with Rp-cAMPS and cAMP indicated the presence of PKA-dependent pathway. The average cumulative ΔCm traces during 200 depolarizing pulses are shown. Error bars are omitted for the sake of clarity. The averaged cumulative ΔCm traces (with/without cAMP) from Fig. 2A are displayed for comparison (grey circles). The inset shows the first few seconds of the cumulative Cm response. B, the averaged cumulative ΔCm traces from 6-Phe-cAMP-, H-89- and H-89/cAMP-treated cells. C, bar graph of cumulative ΔCm. Note differences compared to control: cAMP-treated (P < 0.001) and 6-Phe-cAMP-treated melanotrophs (P < 0.02, one-way ANOVA). D, bar graph of the average slope of linear component. Note statistical differences compared to control: cAMP- (P < 0.001), Rp-cAMPS/cAMP- (P < 0.01), Rp-cAMPS- (P < 0.01) and H-89/cAMP-treated cells (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA). E, bar graph of the peak HVA Ca2+ current amplitudes. Note the significant difference from control with respect to cAMP-treated cells and 6-Phe-cAMP (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA on Ranks). Numbers on bars or in parentheses indicate the number of cells tested. Asterisks indicate statistical significance.

The possible presence of another cAMP-dependent, PKA-independent pathway involved in secretion was tested with Epac agonist, 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP. In fact, when 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP was used the total cumulative ΔCm significantly increased to 1.816 ± 0.299 pF (n = 7; P < 0.02), without affecting HVA Ca2+ amplitude as depicted in Fig. 5. The overall capacitance changes as well as the average slope of the linear component in 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells were indistinguishable from the changes in cells dialysed with 200 μm cAMP (102 ± 23 fF s−1, n = 6; Figs 5A inset and 8D).

Figure 5. Stimulation of PKA-independent pathway in melanotrophs.

A, the averaged cumulative ΔCm trace from 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells (•). B, the cumulative ΔCm, mean ±s.e.m., from control, cAMP-treated and 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells. Note the significant differences compared to control: cAMP-treated and 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated melanotrophs (P < 0.006 and P < 0.02, respectively; one-way ANOVA). C, the peak HVA Ca2+ current amplitudes. No significant difference was found in 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells. Numbers on bars or in parentheses indicate the number of cells tested. Asterisks indicate statistical significance.

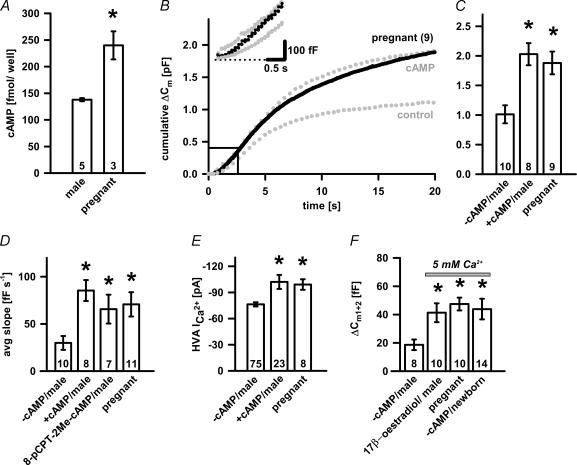

Figure 8. Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in oestrogen-rich melanotrophs.

A, increase in [cAMP]i measured in the oestrogen-rich melanotrophs. [cAMP]i was measured as described in Methods. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.02). Numbers on bars indicate the number of animals tested. B, the averaged cumulative ΔCm trace from melanotrophs of pregnant mice (day 19) resemble the cumulative ΔCm response from the cAMP-treated melanotrophs. C, bar graph of the cumulative ΔCm mean ±s.e.m. from control, cAMP-treated (P < 0.001) and cells from pregnant mice (P < 0.002; one-way ANOVA). D, bar graph of the average slope of the linear component. Note statistical differences compared to control: cAMP- (P < 0.001), 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells (P < 0.03) and cells from pregnant female (P < 0.03; one-way ANOVA). E, bar graph of the peak HVA Ca2+ current amplitudes. Note that pregnant mice show significantly higher peak HVA Ca2+ current amplitudes with respect to control (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Numbers on bars or in parentheses indicate the number of cells tested. F, mean ±s.e.m. for S values (ΔCm1+ΔCm2) were calculated from male control cells (24 h at 37°C no 17β-oestradiol), 17β-oestradiol-treated male melanotrophs (P < 0.04; 1 nm, 24 h at 37°C) and cells from pregnant female mice (P < 0.01) in 5 mm CaCl2 extracellularly, while data for newborn cells were obtained from 2 mm CaCl2 extracellularly (P < 0.03). Overall, oestrogen-rich pituitaries showed about twofold increase in S.

Estimation of the size and kinetic properties of release-ready pools

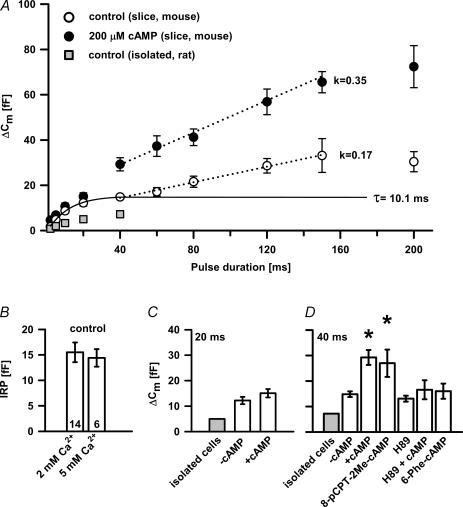

In search of the underlying mechanism responsible for increased early exocytosis, we then used two independent approaches to analyse the influence of cAMP on the size and kinetic properties of releasable pools. In the first approach, we used single depolarization pulses of different duration (between 2 and 200 ms) from −80 mV to 0 mV applied sequentially in random order (Gillis et al. 1996). Fifteen seconds were allowed for pool refilling between pulses shorter than 40 ms and 30 s for longer pulses. First pulses were applied 3 min after the beginning of whole-cell dialysis. Under control conditions, two rapid components of depolarization-induced exocytosis in mouse melanotrophs were obtained (Fig. 6A). The fastest component, reflecting the fusion of the IRP, reached its maximum between 20 and 60 ms. These data were best fitted by a single exponential function, which yielded a time constant (τ) of 10.1 ms (n = 14) and an amplitude of ∼15 fF (Fig. 6A). This corresponded to the release of approximately 15 vesicles using a conversion factor of 1 fF per vesicle (Thomas et al. 1993b). The maximal peak secretory rate (∼950 fF s−1) was elicited at 5 ms pulses, indicating a short delay between the onset of stimulus and full secretory output. The peak secretory rate in cells from tissue slices was more than double that measured in cultured rat melanotrophs (∼400 fF s−1; Table 1) (Mansvelder & Kits, 1998). No significant Ca2+ current inactivation was observed during 40 ms depolarizing pulses, therefore we attributed the saturation of the fast capacitance response to the depletion of the IRP.

Figure 6. The effect of 200 μm cAMP on the size of the pools of release-ready vesicles.

A, ΔCmversus pulse duration in control and cAMP-treated cells. Data points for depolarizations ≤ 40 ms were best fitted by y(x) =y0(1 − exp(−x/τ)3), with τ= 10.1 ms. The dotted straight lines represent linear fits to the ΔCm values measured in response to the depolarizations between 40 and 150 ms. Data are represented as the mean ±s.e.m. of double random stimulation from at least seven cells. The ΔCm data obtained from isolated rat melanotrophs (Mansvelder & Kits, 1998) are displayed for comparison (grey squares). B, by increasing extracellular Ca2+ from 2 to 5 mm no difference was observed in the IRP in control male melanotrophs. Numbers on the bars indicate the number of cells tested. C, ΔCm triggered by a single 20 ms depolarization pulse in isolated rat adult melanotrophs (grey bar), control and cAMP-treated adult mouse melanotrophs (white bars) from tissue slices. D, ΔCm triggered by a single 40 ms depolarization pulse in isolated rat adult melanotrophs (grey bar); control, cAMP-treated, 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated, H-89-treated, H-89 + cAMP-treated and 6-Phe-cAMP-treated adult mouse melanotrophs (white bars) from tissue slices. Note the significantly increased ΔCm between control and cAMP-treated cells (P < 0.001) and 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated melanotrophs (P < 0.02). Data are means ±s.e.m. of double random stimulation from at least seven cells.

Table 1.

Comparison of sizes and kinetic properties of the rapid component of capacitance increase in different neuroendocrine cells

| Cell type | Approx. no. of vesicles/ΔCm (fF) | Secretory rate max. (fF s−1) | Rate constant (s−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromaffin cells | ||||

| Bovine (isolated) | 14/34 | No data | 20–30 | Gillis et al. (1996) |

| Rat (isolated) | 17/34 | 680 | ∼20 | Horrigan & Bookman (1994) |

| Rat (isolated) | 29/29 | No data | ∼12 | Carabelli et al. (2003) |

| Mouse (isolated) | 6/8 | 1300 | ∼30 | Moser & Neher (1997b) |

| Mouse (slice) | 32/42 | 7300 | 143 | Moser & Neher (1997b) |

| Mouse (slice) | 35/45 | 2700 | 150 | Voets et al. (1999) |

| β-Cells | ||||

| Mouse (isolated) | 4/1 | No data | ∼20 | Eliasson et al. (2003) |

| Rat (slice) | 5/16 | 900 | ∼70 | T. Rose et al. (unpublished observation) |

| Melanotrophs | ||||

| Rat (isolated) | 7/7 | 400 | ∼60 | Mansvelder & Kits (1998) |

| Mouse (slice) | 15/15 | 950 | ∼100 | Present paper |

| Mouse newborn | 28/28 | 950 | ∼100 | Present paper |

| Mouse pregnant | 40/40 | 950 | ∼100 | Present paper |

| Mouse 200 μm cAMP | 29/29 | 950 | ∼100 | Present paper |

In our experiments with cAMP, no significant difference in ΔCm was observed after the first short pulses with respect to control cells (Figs 6A and C); however, 40 ms depolarizations evoked an increase in Cm of 26.1 ± 3.7 fF (n = 9) in cAMP-treated cells and 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP-treated cells (27.0 ± 5.4 fF; n = 8), which is significantly larger compared to control cells (13.5 ± 2.3 fF, n = 10, both P < 0.001; Fig. 6D). The following slower component was, as in the control, best fitted by a linear function. The slopes as the estimate for the slow secretory rate were ∼170 fF s−1 and ∼350 fF s−1 for control and cAMP-treated cells, respectively. Pulses of ≥ 200 ms duration showed no further increase in secretion due to the Ca2+ current inactivation. After increasing extracellular [Ca2+] from 2 to 5 mm, no statistical difference in ΔCm was observed (Fig. 6B), indicating that this process was limited by the pool size rather than [Ca2+]i as has also been suggested by (Heinemann et al. 1994).

A comparison of the IRP sizes evoked by 20 ms pulses is presented in Fig. 6C, showing no difference between control and cAMP-treated cells. However, at pulses equal to or longer than 40 ms, cAMP significantly increased the exocytotic response (Fig. 6D), suggesting that equivalent Ca2+ entry at higher cAMP increased the fusion of the release-ready vesicles outside the Ca2+ microdomain. Remarkably, a comparable increase was also achieved in the presence of 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP, demonstrating a cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent underlying mechanism (Fig. 6D).

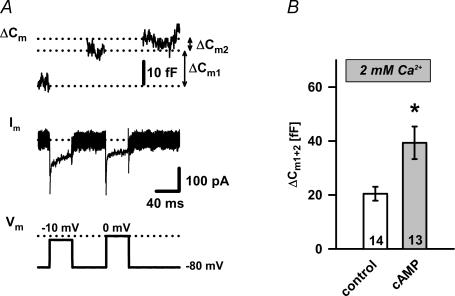

For more accurate estimation of the IRP size, we applied a dual-pulse protocol as previously described (Gillis et al. 1996). Two 40 ms depolarizations separated by a 60 ms interval were chosen to elicit secretory vesicle depletion. Pulse amplitudes were set at −10 mV and 0 mV to obtain two comparable Ca2+ charge injections during both pulses (Fig. 7A). A single set of paired pulses was applied 2 min after the onset of whole-cell mode. Following the analysis of (Gillis et al. 1996), only cells with R < 0.7 can be used (where R=ΔCm2/ΔCm1), as substantial pool depletion is a prerequisite for accurate pool size determinations. While the latter criterion was fulfilled in only less than 60% of cAMP-treated cells in contrast to more than 80% of control cells tested, we could not use this protocol to estimate the IRP size as previously suggested (Gillis et al. 1996). Thus, the sum (S=ΔCm1+ΔCm2), calculated from the capacitance increases, where ΔCm1 is the capacitance response to the first and ΔCm2 to the second depolarization (Fig. 7A), was taken to estimate the number of release-ready vesicles fusing during a dual-pulse protocol. We found that under control conditions this protocol stimulated a fusion of ∼21 vesicles (S: 20.5 ± 2.6 fF), while in cAMP treated cells ∼46 vesicles (45.7 ± 8.5 fF; P < 0.002; Fig. 7B) fused during the same stimulation. As the IRP was not affected (Fig. 6C), cAMP acted primarily on secretory vesicles outside the Ca2+ microdomain.

Figure 7. Dual-pulse protocol in control and cAMP-treated melanotrophs.

A, two pulses were designed to elicit a secretory vesicle depletion and equal the total amount of Ca2+ influx. Paired pulses of 40 ms duration were given 60 ms apart and the potentials of the first and second pulses were adjusted to −10 and 0 mV, respectively. B, means ±s.e.m. for S values (ΔCm1+ΔCm2) were calculated from responses to the dual-pulse 40 ms protocol in the absence (white bars, n = 14) and presence (grey bars, n = 13) of 200 μm cAMP in melanotrophs. Numbers on the bars indicate the number of cells tested. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.002).

17β-Oestradiol and regulation of exocytosis

In oestrogen-rich pituitaries about a twofold increase of secretory activity was observed (Sedej et al. 2004), suggesting that oestrogen might regulate exocytosis by a cAMP-dependent pathway (Zhou et al. 1996). We measured the cytosolic levels of cAMP in adult male and pregnant female mice and found that in neurointermediate lobe from the terminally pregnant mice (day 19), the cAMP levels were significantly increased (P < 0.02; Fig. 8A). Consistent with this, as shown in Fig. 8B, the capacitance response of melanotrophs from pregnant females tightly followed the response from cAMP-treated cells, which resulted in the significantly higher cumulative ΔCm change from control cells and was 1.880 ± 0.192 pF (Fig. 8C; n = 9; P < 0.004). In addition, the peak amplitude of HVA Ca2+ currents was also significantly increased in comparison to control cells (Fig. 8E; −99.1 ± 6.0 pA and 76.3 ± 2.4 pA; P < 0.05, respectively). A linear component was also comparable to the cAMP-treated cells (109 ± 20 fF s−1, n = 13, P < 0.01; Fig. 8B inset and D). Capacitance changes triggered by the depolarization train in melanotrophs from pregnant mice also did not differ from cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-treated cells (Figs 4A and 8B). Next, we were specifically interested in the effect of 17β-oestradiol on the size of the secretory pool released by a pair of 40 ms depolarizations. Melanotrophs from pregnant female and 17β-oestradiol-treated male pituitaries were investigated using the dual-pulse protocol (Fig. 8F). The size of secretory pools released by the protocol in pregnant females (S: 47.5 ± 4.5 fF; n = 10; P < 0.01) and 17β-oestradiol-treated males (S: 38.3 ± 7.4 fF; n = 10; P < 0.04; Fig. 8E) were significantly different from control male melanotrophs incubated for 24 h in the absence of 17β-oestradiol, where the S-value was 18.7 ± 3.7 fF (n = 8). Similarly, as in cAMP-treated cells, newborn melanotrophs also showed significantly elevated capacitance response (S) of 29.3 ± 4.9 fF (n = 14; P < 0.03; Fig. 8F), indicating increased activity of cAMP in these cells. We can conclude that both PKA-dependent and cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 pathway are modulated during increased physiological demand, e.g. during pregnancy.

Discussion

Our primary goal was to assess the effect of cAMP on the Ca2+-dependent exocytosis evoked by depolarization trains in mouse melanotrophs from acute pituitary tissue slices. For this, Ca2+ currents and high-resolution capacitance measurements were used to trace changes in peak Ca2+ current amplitude, size and kinetic properties of the exocytotic process.

The secretory rates obtained in membrane capacitance recordings from melanotrophs in slices are faster than those observed in isolated cells (Fig. 6A and Table 1). The rapid kinetics of secretion in melanotrophs in slices is probably due to the close spatial coupling of release sites and VACCs (Moser & Neher, 1997b). This resulted in a separation of two kinetic components which were not readily seen in cultured pituitary cells (Mansvelder & Kits, 1998). As in numerous previous studies, all the rapid capacitance increases (Figs 6, 7 and 8F) were assumed to reflect purely the exocytosis of large, dense core vesicles, although they may partially represent a group of unidentified synaptic-like vesicles in melanotrophs.

Prior studies of cultured rat melanotrophs using caged calcium released by the flash photolysis suggest an IRP equivalent, the fastest component occurring within 140 ms at 30–34°C (∼250 secretory vesicles) (Thomas et al. 1993a; Horrigan & Bookman, 1994; Parsons et al. 1995; Rupnik et al. 2000). It is, however, not clear whether this fastest kinetic phase is an equivalent to the IRP as elicited by depolarizations. A recently suggested alternative favours a separate, high-calcium sensitive pool (Wan et al. 2004) to represent this initial secretory burst, with low affinity release-ready processes fusing only later.

The results demonstrate that 200 μm cAMP doubles the total cumulative ΔCm in response to a train of depolarizing pulses in adult melanotrophs from slices (Fig. 2A and B). This augmentation is consistent with previously published data from experiments using dialysis in rat melanotrophs (Yamamoto et al. 1987; Lee, 1996; Sikdar et al. 1998). The present study also confirms that increase in intracellular cAMP concentration, and thereby activation of PKA, regulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (Lee, 1996; Sikdar et al. 1998), primarily through the PKA-dependent modulation of the VACCs. In fact, PKA activation by 6-Phe-cAMP, which is a potent activator of PKA (Ogreid et al. 1989), significantly increased the density of the VACCs, which resulted in a 2.5-fold cumulative capacitance increase compared to control (Fig. 4B and C). The increased exocytosis could be partially also due to the weak stimulation of Epac, since it has been shown that several 6-modified cAMP analogues (including 6-Phe-cAMP) were full cAMP-dependent PKA agonists and poor agonists of Epac activation (Christensen et al. 2003). On the other hand, both Rp-cAMPS, a competitive antagonist of cAMP binding to PKA, and H-89, a specific PKA antagonist as well as the cAMP washout in so-called control experiment diminished the VACC density and limited the capacitance change (Fig. 4A–C and E). The cAMP-dependent modulation of the VACCs seems to be the only source for the increase in the cytosolic Ca2+ since cAMP in melanotrophs did not trigger the release from the internal stores (Fig. 3 and Supplemental material Figs 9 and 10 and Movie 1).

It is important to point out that two kinetic components can be readily distinguished using the train of depolarizing pulses, a linear and a threshold component. The initial linear component probably represents the ATP- and PKA-independent fusion (not affected by H-89) of the release-ready vesicles. The rate of the fusion suggests a low Ca2+-affinity process, which can be significantly sped up at higher [Ca2+]i > 10 μm using flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ (Rupnik et al. 2000). This linear component can be selectively stimulated by a cAMP–GEF agonist, 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (Fig. 8D), although the latter has been reported to have also an agonistic action on PKA at the concentration used (100 μm) (Enserink et al. 2002). Interestingly, a similar increase of the linear component was observed in Rp-cAMPS- and Rp-cAMPS/cAMP-treated cells. This argues with the previous published data, where Rp-cAMPS is able to block human cAMP–GEFI/Epac1 (Rehmann et al. 2003). However, the effect of Rp-cAMPS on Epac2 has not been known yet. Our data suggest that the competitive antagonist for PKA might directly activate cAMP–GEFII or it might competitively free cAMP that can then be utilized by cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 (Fig. 4D). The threshold exocytotic component, on the other hand, seems to follow a high Ca2+ affinity dependence (Yang et al. 2002) and is an ATP- and PKA-dependent process. Different densities of VACCs therefore directly influence this delayed secretory response (Sedej et al. 2004). The onset of the threshold component in the presence of increased [Ca2+]i was probably due to the affected dynamics of vesicle mobilization, priming and fusion, as demonstrated in chromaffin cells (Heinemann et al. 1994). However, it is unknown whether cAMP affects the priming process directly.

Among possible mechanisms that could be responsible for the cAMP-dependent increase of Ca2+-dependent secretory activity, two might account for this. First, high cAMP increased the peak HVA Ca2+ current amplitude by about 34% (Fig. 2C and D), presumably through phosphorylation by PKA (Dolphin, 1995; Carabelli et al. 2003). However, the 34% increase in the HVA peak Ca2+ current amplitude measured in our cells (cAMP- and 6-Phe-cAMP-treated) can only partially explain the twofold increase of exocytosis, since a linear relationship between Ca2+ charge and exocytosis was observed (Mansvelder & Kits, 1998). Second, it is possible that the increase in the secretory vesicle size is the mechanism underlying the enlarged contribution of the fusion of secretory vesicles outside of the Ca2+ microdomains to the Ca2+-dependent capacitance change. The increase in secretory activity by cAMP is associated with an increase in the size of unitary exocytotic events in rat melanotrophs (Sikdar et al. 1998), rat chromaffin cells (Carabelli et al. 2003) and pancreatic β-cells (Smith et al. 1995). However, the underlying molecular mechanism is not yet known. From our data, it is tempting to speculate that the cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent pathway is involved in the pre-exocytotic fusion of the release-ready secretory vesicles (Supplemental material Fig. 11). We expected that the effect of cAMP on membrane capacitance in cells treated with H-89 would resemble those with 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP. Indeed, cAMP did have an effect together with H-89 treatment, since the average slope of the capacitance change was significantly increased (Fig. 4D) and comparable to 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (Fig. 8D). However, as one might argue, we failed to demonstrate this effect with the single pulse capacitance analysis (Fig. 6D).

The increase in HVA Ca2+ current amplitude was observed in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 2C and D) and 6-Phe-cAMP (Fig. 4E). However, after the PKA block by Rp-cAMPS and H-89, cAMP dialysis failed to increase the amplitude of HVA Ca2+ current (Fig. 4E). The activation of cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent pathway by 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (Fig. 5C) did not modify the VACC amplitude, which is in line with the view that these channels are modulated by PKA (Dolphin, 1995). 6-Phe-cAMP activation of PKA significantly increased the VACC density and also the delayed threshold component of the Ca2+-dependent secretory activity suggesting this delayed exocytosis depended on the PKA-dependent modulation of Ca2+ channels (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the early linear component which showed sensitivity to cAMP–GEF/Epac modulator (8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP) did not seem to depend on the VACC density since the secretion was augmented despite the unchanged density of VACCs. One of the multifaceted effects of oestrogen is the ability to activate adenylyl cyclase and increase cAMP levels in the cells within minutes after exposure to the hormone (Gu & Moss, 1996). However, the rapid onset of the 17β-oestradiol effect in slices was not observed during the initial 10 min of the whole-cell dialysis. This indicates that increased L-type VACC density and Ca2+-dependent secretory activity under higher oestrogen levels might be a genomic effect (Sedej et al. 2004). In addition to the direct genomic effects via classical nuclear oestrogen receptors, oestrogen can activate intracellular signalling pathways to indirectly affect genomic activity via other transcriptional regulators like cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) (Aronica et al. 1994; Wade & Dorsa, 2003). A possible cross-talk of rapid oestrogen signalling with genomic oestrogen actions might be involved in cAMP action in melanotrophs, since increased cAMP levels were found in the melanotrophs of pregnant mice (Fig. 8A). Given that 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP stimulated the secretory response in a very similar manner to cAMP (Fig. 4A) and accurately mimicked the response in melanotrophs of pregnant mice (Fig. 8B), our study implies a novel physiological role of the cAMP–GEFII/Epac2-dependent mechanism.

In conclusion, our data suggest that cAMP–GEFII/Epac2 mediates an increase in efficacy of cytosolic Ca2+ to recruit release-ready vesicles, thus strengthening stimulus–secretion coupling and significantly increasing peptide hormone output during increased physiological demand, e.g. during pregnancy. The kinetic separation of release-ready vesicles and both cAMP-dependent pathways form a basis for future analysis of the role of proteins involved in late steps of Ca2+-dependent exocytosis.

Acknowledgments

We cordially thank Professor Erwin Neher for critical reading of an earlier version of manuscript and valuable suggestions. We thank Professor Susumu Seino for information on expression of Epac2 in mouse melanotrophs and Professor Claes Wollheim for his help concerning the cAMP-ELISA assay. We also thank Marion Niebeling and Heiko Röhse for excellent technical support and Primoz Pirih for suggestions regarding the mean exocytotic vesicle size estimation. The work was supported by Center for Molecular Physiology of the Brain (DFG).

Supplemental material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2005.090381/DC1 and contains supplemental material consisting of three figures and a video:

Figure 9. Mean exocytotic vesicle size

Figure 10. Adult pituitary tissue slice

Figure 11. Mean exocytotic vesicle size

Movie 1. The effect of forskolin on the [Ca2+]i changes in the pituitary tissue slice

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Ämmälä C, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Calcium-independent potentiation of insulin release by cyclic AMP in single beta-cells. Nature. 1993;363:356–358. doi: 10.1038/363356a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica SM, Kraus WL, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen action via the cAMP signaling pathway: stimulation of adenylate cyclase and cAMP-regulated gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8517–8521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli V, Giancippoli A, Baldelli P, Carbone E, Artalejo AR. Distinct potentiation of L-type currents and secretion by cAMP in rat chromaffin cells. Biophys J. 2003;85:1326–1337. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74567-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Stevens CF. Increased transmitter release at excitatory synapses produced by direct activation of adenylate cyclase in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 1994;14:310–317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00310.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AE, Selheim F, de Rooij J, Dremier S, Schwede F, Dao KK, et al. cAMP analog mapping of Epac1 and cAMP kinase. Discriminating analogs demonstrate that Epac and cAMP kinase act synergistically to promote PC-12 cell neurite extension. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35394–35402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J, Rehmann H, van Triest M, Cool RH, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Mechanism of regulation of the Epac family of cAMP-dependent RapGEFs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20829–20836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. The G.L. Brown Prize Lecture. Voltage-dependent calcium channels and their modulation by neurotransmitters and G proteins. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:1–36. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufy B, Vincent JD, Fleury H, Du Pasquier P, Gourdji D, Tixier-Vidal A. Dopamine inhibition of action potentials in a prolactin secreting cell line is modulated by oestrogen. Nature. 1979;282:855–857. doi: 10.1038/282855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson L, Ma X, Renstrom E, Barg S, Berggren PO, Galvanovskis J, et al. SUR1 regulates PKA-independent cAMP-induced granule priming in mouse pancreatic B-cells. J General Physiol. 2003;121:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink JM, Christensen AE, de Rooij J, van Triest M, Schwede F, Genieser HG, et al. A novel Epac-specific cAMP analogue demonstrates independent regulation of Rap1 and ERK. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:901–906. doi: 10.1038/ncb874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey EA, Cote TE, Grewe CW, Kebabian JW. [3H]spiroperidol identifies a D-2 dopamine receptor inhibiting adenylate cyclase activity in the intermediate lobe of the rat pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1897–1904. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-6-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis KD, Mossner R, Neher E. Protein kinase C enhances exocytosis from chromaffin cells by increasing the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory granules. Neuron. 1996;16:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomora JC, Avila G, Cota G. Ca2+ current expression in pituitary melanotrophs of neonatal rats and its regulation by D2 dopamine receptors. J Physiol. 1996;492:763–773. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Moss RL. 17beta-Estradiol potentiates kainate-induced currents via activation of the cAMP cascade. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3620–3629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03620.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann C, Chow RH, Neher E, Zucker RS. Kinetics of the secretory response in bovine chromaffin cells following flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ Biophys J. 1994;67:2546–2557. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofland LJ, van Koetsveld P, Koper JW, den Holder A, Lamberts SW. Weak estrogenic activity of phenol red in the culture medium: its role in the study of the regulation of prolactin release in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1987;54:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(87)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan FT, Bookman RJ. Na channel gating charge movement is responsible for the transient capacitance increase evoked by depolarization in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophys J. 1993;64:A101–A101. [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan FT, Bookman RJ. Releasable pools and the kinetics of exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1994;13:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, et al. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998;282:2275–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AK. Dopamine (D2) receptor regulation of intracellular calcium and membrane capacitance changes in rat melanotrophs. J Physiol. 1996;495:627–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado JD, Alonso C, Morales A, Borges R. A novel nongenomic action of estrogens: the regulation of exocytotic kinetics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;971:284–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Eipper BA. Synthesis and secretion of corticotropins, melanotropins, and endorphins by rat intermediate pituitary cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:7885–7894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, Kits KS. The relation of exocytosis and rapid endocytosis to calcium entry evoked by short repetitive depolarizing pulses in rat melanotropic cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:81–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millington WR, Chronwall BM. Dopaminergic regulation of the intermediate pituitary. In: Muller EE, MacLeod RM, editors. Neuroendocrine Perspectives. vol. 7. New York: Springer Verlag; 1989. pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A, Roth D, Martin H, Aitken A, Burgoyne RD. Identification of cytosolic protein regulators of exocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:401–405. doi: 10.1042/bst0210401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser T, Neher E. Estimation of mean exocytic vesicle capacitance in mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997a;94:6735–6740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser T, Neher E. Rapid exocytosis in single chromaffin cells recorded from mouse adrenal slices. J Neurosci. 1997b;17:2314–2323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemura M, Eskay RL, Kebabian JW. Release of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone from dispersed cells of the intermediate lobe of the rat pituitary gland: involvement of catecholamines and adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1795–1803. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-6-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Marty A. Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogreid D, Ekanger R, Suva RH, Miller JP, Doskeland SO. Comparison of the two classes of binding sites (A and B) of type I and type II cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinases by using cyclic nuclectide analogs. Eur J Biochem. 1989;181:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano K, Monck JR, Fernandez JM. GTP gamma S stimulates exocytosis in patch-clamped rat melanotrophs. Neuron. 1993;11:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki N, Shibasaki T, Kashima Y, Miki T, Takahashi K, Ueno H, et al. cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:805–811. doi: 10.1038/35041046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons TD, Coorssen JR, Horstmann H, Almers W. Docked granules, the exocytic burst, and the need for ATP hydrolysis in endocrine cells. Neuron. 1995;15:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmann H, Schwede F, Doskeland SO, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Ligand-mediated activation of the cAMP-responsive guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38548–38556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie AK. Estrogen increases low voltage-activated calcium current density in GH3 anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1621–1629. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupnik M, Kreft M, Sikdar SK, Grilc S, Romih R, Zupancic G, et al. Rapid regulated dense-core vesicle exocytosis requires the CAPS protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5627–5632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090359097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Lopez-Barneo J. Patch-clamp analysis of voltage-gated currents in intermediate lobe cells from rat pituitary thin slices. Pflugers Arch. 1992;420:302–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00374463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedej S, Tsujimoto T, Zorec R, Rupnik M. Voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and their role in the endocrine function of the pituitary gland in newborn and adult mice. J Physiol. 2004;555:769–782. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar SK, Kreft M, Zorec R. Modulation of the unitary exocytic event amplitude by cAMP in rat melanotrophs. J Physiol. 1998;511:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.851bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Duchen MR, Ashcroft FM. A fluorimetric and amperometric study of calcium and secretion in isolated mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:808–818. doi: 10.1007/BF00386180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JB. Formation, stabilisation and fusion of the readily releasable pool of secretory vesicles. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Surprenant A, Almers W. Cytosolic Ca2+, exocytosis, and endocytosis in single melanotrophs of the rat pituitary. Neuron. 1990;5:723–733. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Wong JG, Almers W. Millisecond studies of secretion in single rat pituitary cells stimulated by flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ EMBO J. 1993a;12:303–306. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Wong JG, Lee AK, Almers W. A low affinity Ca2+ receptor controls the final steps in peptide secretion from pituitary melanotrophs. Neuron. 1993b;11:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90274-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J-E, Sedej S, Rupnik M. Cytosolic Cl− ions in the regulation of secretory and endocytotic activity in melanotrophs from mouse pituitary tissue slices. J Physiol. 2005;566:433–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. Mechanisms underlying phasic and sustained secretion in chromaffin cells from mouse adrenal slices. Neuron. 1999;23:607–615. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorndran C, Minta A, Poenie M. New fluorescent calcium indicators designed for cytosolic retention or measuring calcium near membranes. Biophys J. 1995;69:2112–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade CB, Dorsa DM. Estrogen activation of cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate response element-mediated transcription requires the extracellularly regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2003;144:832–838. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan QF, Dong Y, Yang H, Lou X, Ding J, Xu T. Protein kinase activation increases insulin secretion by sensitizing the secretory machinery to Ca2+ J General Physiol. 2004;124:653–662. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Furuki Y, Guild S, Kebabian JW. Adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate stimulates secretion of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone from permeabilized cells of the intermediate lobe of the rat pituitary gland. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;143:1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Udayasankar S, Dunning J, Chen P, Gillis KD. A highly Ca2+-sensitive pool of vesicles is regulated by protein kinase C in adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17060–17065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242624699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong N, Zucker RS. cAMP acts on exchange protein activated by cAMP/cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange protein to regulate transmitter release at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2005;25:208–214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3703-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Watters JJ, Dorsa DM. Estrogen rapidly induces the phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2163–2166. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Hille B, Xu T. Sensitization of regulated exocytosis by protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17055–17059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232588899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorec R, Sikdar SK, Mason WT. Increased cytosolic calcium stimulates exocytosis in bovine lactotrophs. Direct evidence from changes in membrane capacitance. J General Physiol. 1991;97:473–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.