Abstract

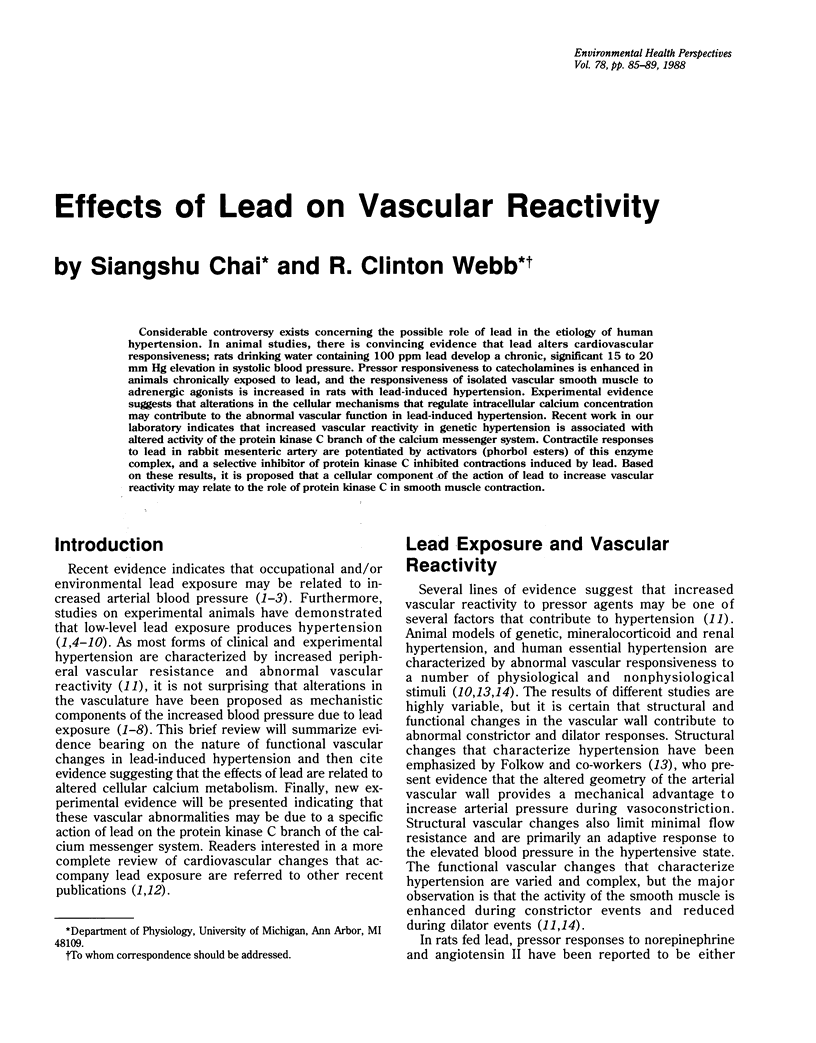

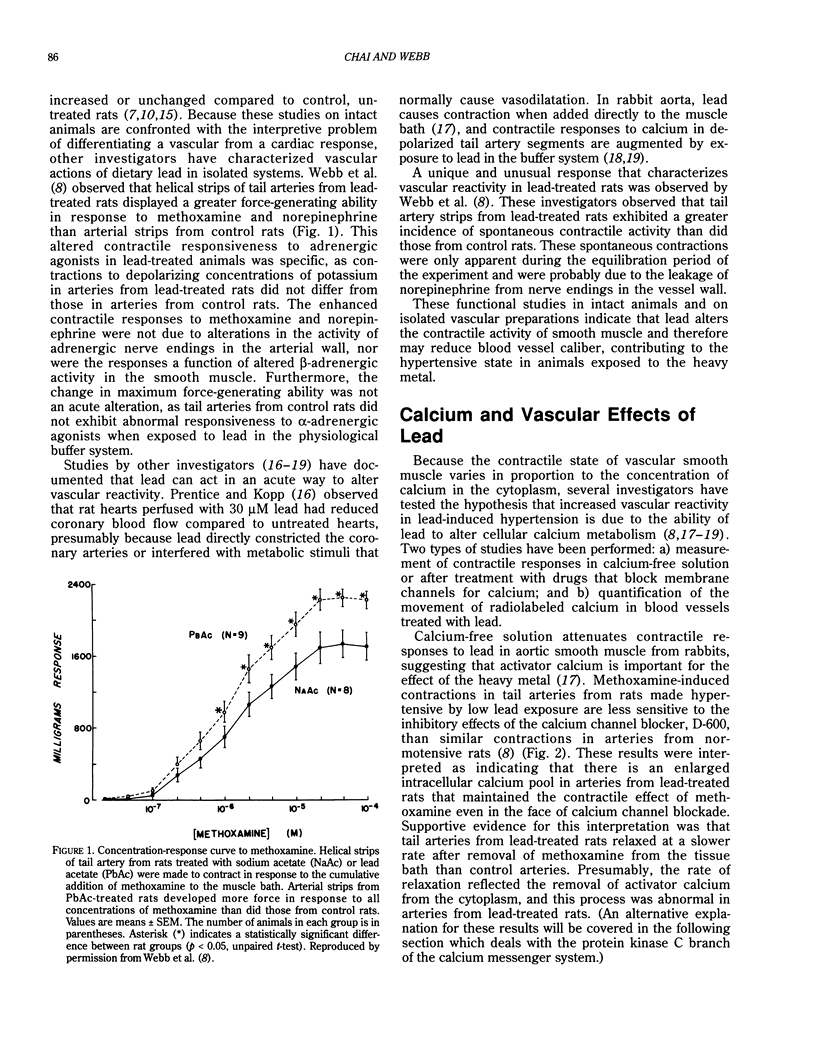

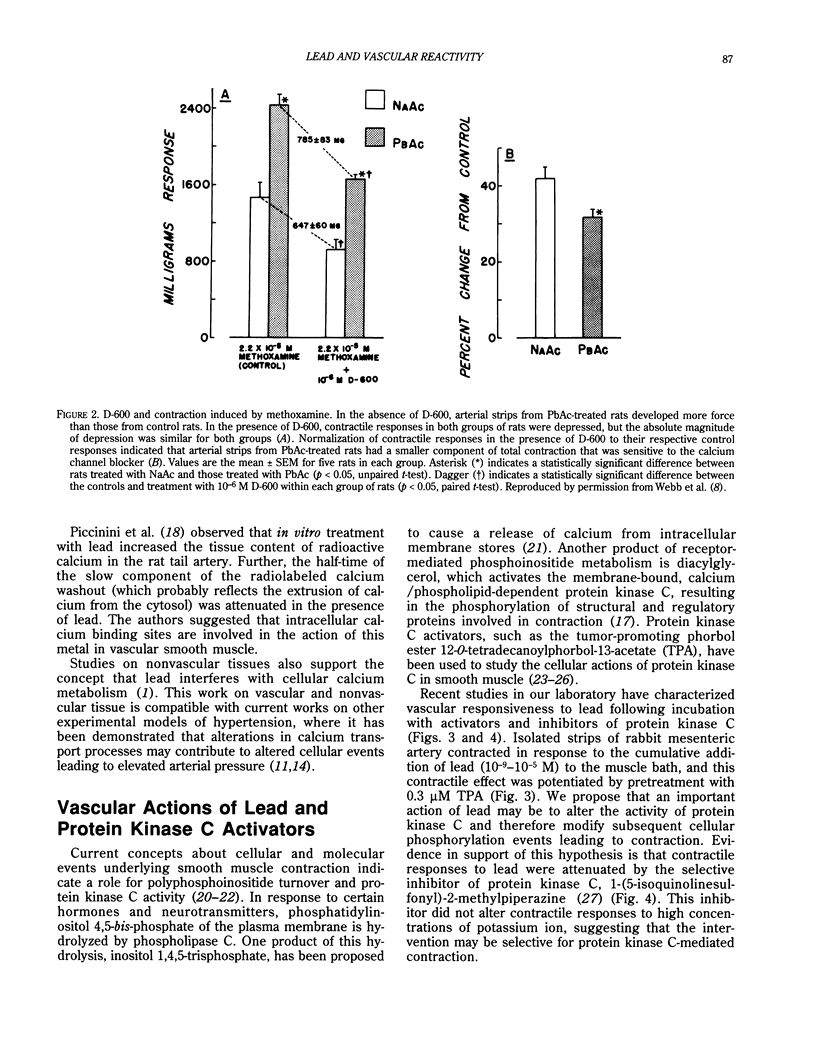

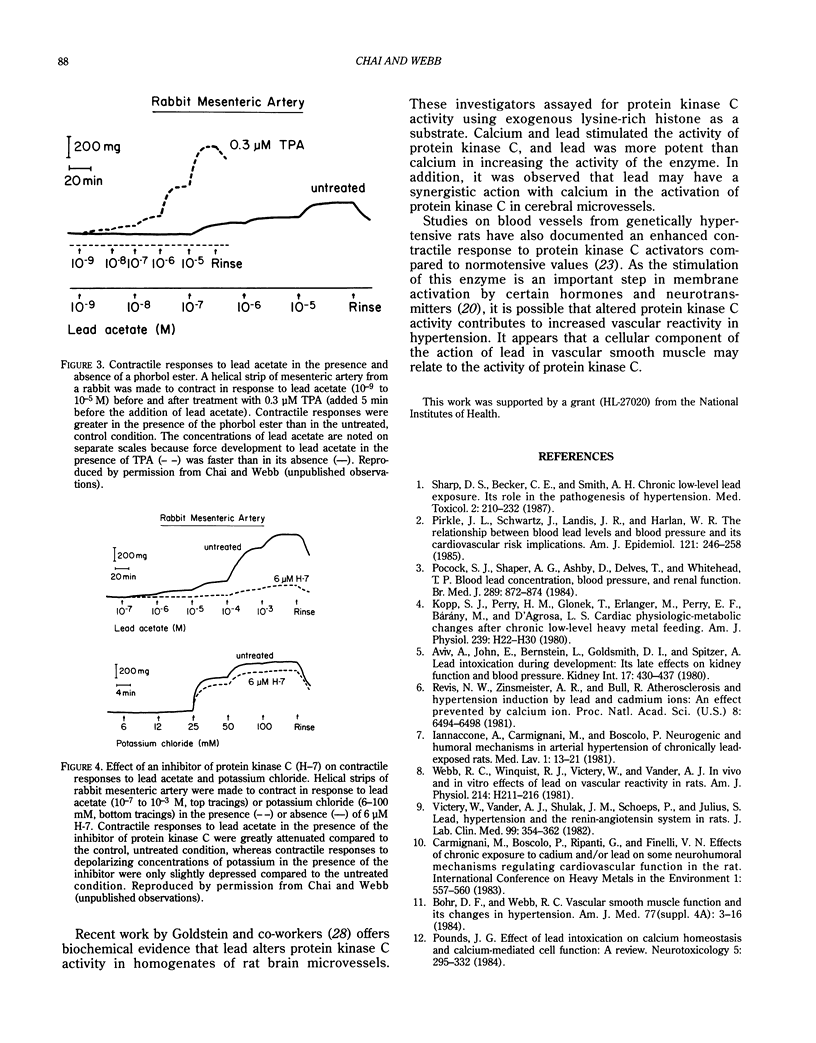

Considerable controversy exists concerning the possible role of lead in the etiology of human hypertension. In animal studies, there is convincing evidence that lead alters cardiovascular responsiveness; rats drinking water containing 100 ppm lead develop a chronic, significant 15 to 20 mm Hg elevation in systolic blood pressure. Pressor responsiveness to catecholamines is enhanced in animals chronically exposed to lead, and the responsiveness of isolated vascular smooth muscle to adrenergic agonists is increased in rats with lead-induced hypertension. Experimental evidence suggests that alterations in the cellular mechanisms that regulate intracellular calcium concentration may contribute to the abnormal vascular function in lead-induced hypertension. Recent work in our laboratory indicates that increased vascular reactivity in genetic hypertension is associated with altered activity of the protein kinase C branch of the calcium messenger system. Contractile responses to lead in rabbit mesenteric artery are potentiated by activators (phorbol esters) of this enzyme complex, and a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C inhibited contractions induced by lead. Based on these results, it is proposed that a cellular component of the action of lead to increase vascular reactivity may relate to the role of protein kinase C in smooth muscle contraction.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aviv A., John E., Bernstein J., Goldsmith D. I., Spitzer A. Lead intoxication during development: its late effects on kidney function and blood pressure. Kidney Int. 1980 Apr;17(4):430–437. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol as second messengers. Biochem J. 1984 Jun 1;220(2):345–360. doi: 10.1042/bj2200345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr D. F., Webb R. C. Vascular smooth muscle function and its changes in hypertension. Am J Med. 1984 Oct 5;77(4A):3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(84)80032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danthuluri N. R., Deth R. C. Phorbol ester-induced contraction of arterial smooth muscle and inhibition of alpha-adrenergic response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 Dec 28;125(3):1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favalli L., Chiari M. C., Piccinini F., Rozza A. Experimental investigations on the contraction induced by lead in arterial smooth muscle. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1977;41 (Suppl 2):412–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkow B. Physiological aspects of primary hypertension. Physiol Rev. 1982 Apr;62(2):347–504. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forder J., Scriabine A., Rasmussen H. Plasma membrane calcium flux, protein kinase C activation and smooth muscle contraction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985 Nov;235(2):267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto S., Hidaka H. 1-(5-Isoquinolinesulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine (H-7) is a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C in rabbit platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 Nov 30;125(1):258–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S. J., Perry M., Jr, Glonek T., Erlanger M., Perry E. F., Bárány M., D'Agrosa L. S. Cardiac physiologic-metabolic changes after chronic low-level heavy metal feeding. Am J Physiol. 1980 Jul;239(1):H22–H30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.1.H22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini F., Favalli L., Chiari M. C. Experimental investigations on the contraction induced by lead in arterial smooth muscle. Toxicology. 1977 Aug;8(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(77)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle J. L., Schwartz J., Landis J. R., Harlan W. R. The relationship between blood lead levels and blood pressure and its cardiovascular risk implications. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Feb;121(2):246–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J., Shaper A. G., Ashby D., Delves T., Whitehead T. P. Blood lead concentration, blood pressure, and renal function. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Oct 6;289(6449):872–874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6449.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pounds J. G. Effect of lead intoxication on calcium homeostasis and calcium-mediated cell function: a review. Neurotoxicology. 1984 Fall;5(3):295–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice R. C., Kopp S. J. Cardiotoxicity of lead at various perfusate calcium concentrations: functional and metabolic responses of the perfused rat heart. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1985 Dec;81(3 Pt 1):491–501. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H., Takuwa Y., Park S. Protein kinase C in the regulation of smooth muscle contraction. FASEB J. 1987 Sep;1(3):177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revis N. W., Zinsmeister A. R., Bull R. Atherosclerosis and hypertension induction by lead and cadmium ions: an effect prevented by calcium ion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Oct;78(10):6494–6498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp D. S., Becker C. E., Smith A. H. Chronic low-level lead exposure. Its role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Med Toxicol. 1987 May-Jun;2(3):210–232. doi: 10.1007/BF03259865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. G., 3rd, Seymour A. A., Mazack E. K., Boger J., Blaine E. H. Comparison of a new renin inhibitor and enalaprilat in renal hypertensive dogs. Hypertension. 1987 Feb;9(2):150–156. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo A. V., Bond M., Somlyo A. P., Scarpa A. Inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Aug;82(15):5231–5235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomera J. F., Harakal C. Mercury- and lead-induced contraction of aortic smooth muscle in vitro. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1986 Oct;283(2):295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victery W., Vander A. J., Shulak J. M., Schoeps P., Julius S. Lead, hypertension, and the renin-angiotensin system in rats. J Lab Clin Med. 1982 Mar;99(3):354–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R. C., Winquist R. J., Victery W., Vander A. J. In vivo and in vitro effects of lead on vascular reactivity in rats. Am J Physiol. 1981 Aug;241(2):H211–H216. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.241.2.H211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. J., Griffith W. H., 3rd, Albrecht C. M., Pirch J. H., Hejtmancik M. R., Jr Effects of chronic lead treatment on some cardiovascular responses to norepinephrine in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1977 Jun;40(3):407–413. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(77)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]