Abstract

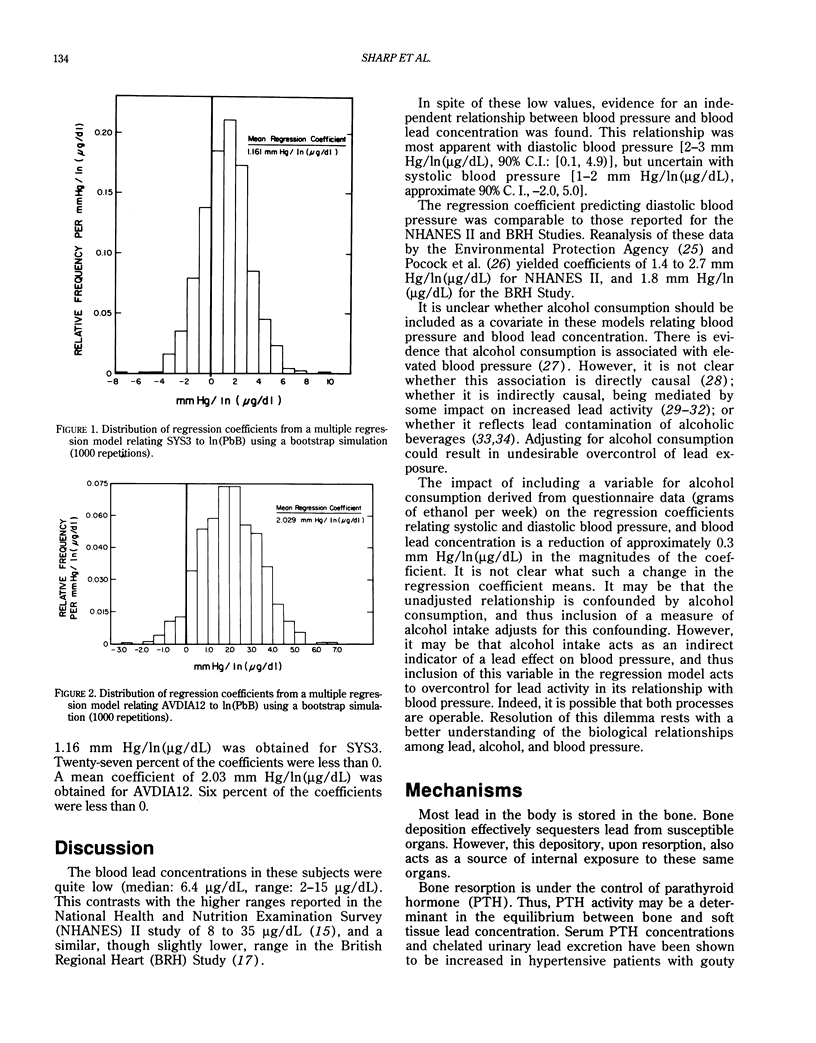

San Francisco bus drivers have an increased prevalence of hypertension. This study examined relationships between blood lead concentration and blood pressure in 342 drivers. The analysis reported in this study was limited to subjects not on treatment for hypertension (n = 288). Systolic and diastolic pressures varied from 102 to 173 mm Hg and from 61 to 105 mm Hg, respectively. The blood lead concentration varied from 2 to 15 micrograms/dL. The relationship between blood pressure and the logarithm of blood lead concentration was examined using multiple regression analysis. Covariates included age, body mass index, sex, race, and caffeine intake. The largest regression coefficient relating systolic blood pressure and blood lead concentration was 1.8 mm Hg/ln (micrograms/dL) [90% C. I., -1.6, 5.3]. The coefficient for diastolic blood pressure was 2.5 mm Hg/ln (micrograms/dL) [90% C. I., 0.1, 4.9]. These findings suggest effects of lead exposure at lower blood lead concentrations than those concentrations that have previously been linked with increases in blood pressure.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BERG K. J., MELKILD A. Coronary disease in a group of Norwegian tram drivers. Acta Med Scand. 1962 Jun;171:671–677. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1962.tb04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman A. L. Health survey of professional drivers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1983 Feb;9(1):30–35. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batuman V., Landy E., Maesaka J. K., Wedeen R. P. Contribution of lead to hypertension with renal impairment. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jul 7;309(1):17–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307073090104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton G. H., Milner J., Corey P., McGuire V., Cousins M., Stewart E., de Ramos M., Hewitt D., Grambsch P. V., Kassim N. Sources of variance in 24-hour dietary recall data: implications for nutrition study design and interpretation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979 Dec;32(12):2546–2559. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.12.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton G. H., Milner J., McGuire V., Feather T. E., Little J. A. Source of variance in 24-hour dietary recall data: implications for nutrition study design and interpretation. Carbohydrate sources, vitamins, and minerals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983 Jun;37(6):986–995. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.6.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D., Leviton A., Waternaux C., Needleman H., Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987 Apr 23;316(17):1037–1043. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortoli A., Mattiello G., Zotti S., Bonvicini P., Trabuio G., Fazzin G. Blood-lead levels in patients with chronic liver diseases. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1983;52(1):49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00380607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleoni N., D'Amico G. Chronic lead accumulation as a possible cause of renal failure in gouty patients. Nephron. 1986;44(1):32–35. doi: 10.1159/000183908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope R. F., Pancamo B. P., Rinehart W. E., Ter Haar G. L. Personnel monitoring for tetraalkyl lead in the workplace. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1979 May;40(5):372–379. doi: 10.1080/15298667991429714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dally S., Danan M., Buisine A., Hispard E., Girre C., Fournier P. E. Elévation de la plombémie au cours de l'alcoolisme. Relation avec la pression artérielle. Presse Med. 1986 Jun 28;15(26):1227–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flindt M. L., King E., Walsh D. B. Blood lead and erythrocyte delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase levels in Manchester taxi drivers. Br J Ind Med. 1976 May;33(2):79–84. doi: 10.1136/oem.33.2.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman G. D., Klatsky A. L., Siegelaub A. B. Alcohol intake and hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1983 May;98(5 Pt 2):846–849. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P., Olsen N. B., Hollnagel H. Influence of smoking and alcohol consumption on blood lead levels. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1981;48(4):391–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00378687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasmick C., Huel G., Moreau T., Sarmini H. The combined effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on the level of lead and cadmium in blood. Sci Total Environ. 1985 Mar 1;41(3):207–217. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(85)90142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan W. R., Landis J. R., Schmouder R. L., Goldstein N. G., Harlan L. C. Blood lead and blood pressure. Relationship in the adolescent and adult US population. JAMA. 1985 Jan 25;253(4):530–534. doi: 10.1001/jama.253.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartvig P., Midttun O. Coronary heart disease risk factors in bus and truck drivers. A controlled cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1983;52(4):353–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02226900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D. R., Jr, Anderson J. T., Blackburn H. Diet and serum cholesterol: do zero correlations negate the relationship? Am J Epidemiol. 1979 Jul;110(1):77–87. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. D., Commins B. T., Cernik A. A. Blood lead and carboxyhaemoglobin levels in London taxi drivers. Lancet. 1972 Aug 12;2(7772):302–303. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92907-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Stamler J., Dyer A., McKeever J., McKeever P. Statistical methods to assess and minimize the role of intra-individual variability in obscuring the relationship between dietary lipids and serum cholesterol. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(6-7):399–418. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon S. W., Norton R. N. Alcohol and hypertension: implications for prevention and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1986 Jul;105(1):124–126. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-1-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid E., Hilden M. Elevated levels of blood lead in alcoholic liver disease. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1975 Jul 11;35(1):61–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01266326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau T., Orssaud G., Juguet B., Busquet G. Plombémie et pression artérielle. Premiers résultats d'une enquête transversale de 431 sujets de sexe masculin. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1982;30(3):395–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Kagan A., Pattison D. C., Gardner M. J. Incidence and prediction of ischaemic heart-disease in London busmen. Lancet. 1966 Sep 10;2(7463):553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)93034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netterstrøm B., Laursen P. Incidence and prevalence of ischaemic heart disease among urban busdrivers in Copenhagen. Scand J Soc Med. 1981;9(2):75–79. doi: 10.1177/140349488100900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen N. B., Hollnagel H., Grandjean P. Indicators of lead exposure in an adult Danish suburban population. Dan Med Bull. 1981 Sep;28(4):168–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle J. L., Schwartz J., Landis J. R., Harlan W. R. The relationship between blood lead levels and blood pressure and its cardiovascular risk implications. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Feb;121(2):246–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J., Shaper A. G., Ashby D., Delves T., Whitehead T. P. Blood lead concentration, blood pressure, and renal function. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Oct 6;289(6449):872–874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6449.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland D. R., Winkleby M. A., Schwalbe J., Holman B. L., Morse L., Syme S. L., Fisher J. M. Prevalence of hypertension in bus drivers. Int J Epidemiol. 1987 Jun;16(2):208–214. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi C., Arosio G., Orlando G., Petroboni V., Riva S., Gola E., Benedini G., Cicogna R., Frau G., Prandini B. D. Fattori di rischio coronarico e cardiopatia ischemica nei conduttori e nei bigliettari di autobus. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1975 Nov;23(11):718–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempos C. T., Johnson N. E., Smith E. L., Gilligan C. Effects of intraindividual and interindividual variation in repeated dietary records. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Jan;121(1):120–130. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp D. S., Becker C. E., Smith A. H. Chronic low-level lead exposure. Its role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Med Toxicol. 1987 May-Jun;2(3):210–232. doi: 10.1007/BF03259865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victery W., Miller C. R., Zhu S. Y., Goyer R. A. Effect of different levels and periods of lead exposure on tissue levels and excretion of lead, zinc, and calcium in the rat. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1987 May;8(4):506–516. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(87)90136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedeen R. P., Malik D. K., Batuman V. Detection and treatment of occupational lead nephropathy. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Jan;139(1):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S. T., Muñoz A., Stein A., Sparrow D., Speizer F. E. The relationship of blood lead to blood pressure in a longitudinal study of working men. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 May;123(5):800–808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]