Abstract

Interaction between signaling pathways regulates many cellular functions, including proliferation. The Gαs/cAMP pathway is known to inhibit signal flow from receptor tyrosine kinases to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-1,2 and, thus, inhibit proliferation. Elevation of cAMP or adenovirus-directed expression of mutant (Q227L)–Gαs (αs*) inhibits the proliferation of rat vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in culture. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulated MAPK activation and DNA synthesis was also blocked by expression of αs*. However, it is not known whether such mechanisms are operative in vivo. Proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo was induced by balloon injury of carotid arteries in the rat. Recombinant adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase (β-gal) or αs* was applied to arterial segments injured by the balloon catheters. The αs*-treated vessels showed decreased phospho-MAPK staining in the intima as compared with β-gal-treated vessels. Application of αs*, but not β-gal containing adenovirus, inhibited formation of neointima by 50%. No change was observed in total vessel diameter or in the media or adventitia. These results suggest that the interaction between the Gαs and MAPK pathways can regulate proliferation in vivo and that targeted expression of activated Gαs may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of vascular pathophysiologies that arise from intimal hyperplasia.

Balance between positive and negative signals regulates the proliferative status of cells. It is now well established that signals from receptor tyrosine kinases and Ras through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-1,2 trigger proliferation of many cell types (1, 2), including vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs; ref. 3). Conversely, elevation of cAMP blocks the proliferation of several cell types, including VSMCs (4, 5). The inhibitory effects of cAMP result from protein kinase A phosphorylation of c-Raf that blocks signal flow from Raf to MEK-1,2 (6). Inhibition of signal flow to MAPK-1,2 has substantial biological consequences. In NIH 3T3 cells, expression of mutant (Q227L)-activated Gαs (αs*) results in suppression of Ras-induced transformation (7). Expression of αs* in human breast cancer cell lines blocks their ability to form tumors in Nu/Nu mice (8). These observations suggest that targeted expression of αs* could be useful in regulating proliferation in vivo. Balloon angioplasty is widely used to treat stenotic blood vessels (9, 10). Its utility is limited in part by restenosis, which occurs in up to 40% of cases within a few months (11). The causes of restenosis appear to be different in different species (12), although smooth muscle proliferation is thought to play a role in all cases. In rat blood vessels, balloon catheter-induced injury results in proliferation of smooth muscle cells in a reproducible manner such that this system has emerged as an experimental model for the study of smooth muscle proliferation in the intact animal (13). We were interested in determining whether expression of αs* could regulate MAPK activation and proliferation of VSMCs in vivo. To address these issues we used an adenovirus vector to deliver αs* to the site of balloon catheter-induced injury in rat carotid arteries and determined the effect of αs* expression on neointima formation.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Retired male breeder rats (Sprague–Dawley from Taconic Farms), weighing 380–450 g, were used for all of the animal experiments. Balloon catheters (2F) were from Baxter Allegiance Health Care, McGaw Park, IL. Phospho-MAPK antibodies were from New England Biolabs. Recombinant adenovirus containing β-galactosidase (ADV-β-gal) was a gift of Karsten Pippel (Duke University Medical Center). Adenovirus containing Q227L-Gαs with a FLAG epitope inserted between the third and fourth nucleotide of Gαs* with respect to the initiating was constructed as described in ref. 14. Sources of all other materials have been recently described (15).

Cell Culture.

VSMCs were obtained from rat aorta as described in ref. 16 and grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells used were between passages 7 and 12. Subconfluent cells were used for all experiments. When required, 8Br-cAMP was added to DMEM containing 10% FBS to give a final concentration of 100 μM. For long-term treatment, the medium containing 8Br-cAMP was changed every 2 days. For infection of VSMCs with ADV-β-gal and ADV-αs*, a representative plate of VSMCs was counted to determine the number of cells in each plate. Required amounts of recombinant adenovirus were used to obtain a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 200. Stock virus solutions were at a titer of 1 × 1011 plaque-forming units (pfu)/ml. Cells infected with recombinant adenovirus were counted daily in triplicate.

cAMP Measurements.

Subconfluent VSMCs were either exposed to 200 moi of virus (either containing ADV-β-gal or ADV-αs) or left untreated for 48 h. Cells were labeled for 24 h with 2 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq)/ml [3H]adenine in serum-free 0.1% BSA/DMEM. Cells were then washed twice with DMEM/Hepes solution followed by incubation in DMEM, 300 μM RO 20–174, and 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were extracted in cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 0.5 mM ATP, and 0.5 mM cAMP solution. Accumulation of cAMP was measured as described in ref. 17 and expressed as [3H]cAMP/([3H]ATP + [3H]cAMP)(10−3).

DNA Synthesis.

Incorporation of 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was used to measure DNA synthesis. VSMCs (6 × 103) were cultured in individual wells to 50% confluence in a 96-well microtiter plate (flat bottom). The following day, VSMCs were split into three groups. The first two groups were exposed to 200 moi of virus (either containing ADV-β-gal or ADV-αs*) and the third group left untreated. After 24 h, the three groups of cells were serum starved in 0.1% BSA/DMEM for an additional 24 h. Each group of cells was either incubated in 10 ng/ml PDGF and 10 μM BrdU or 10 μM BrdU by itself for an additional 24 h. The culture medium containing BrdU was removed. Cells were gently washed once with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized in 0.2% Triton in PBS for 15 min. Cells were treated in 10% FCS, 0.1% Triton, in PBS, for 30 min to block nonspecific binding. Anti-BrdU antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) at 0.2 units/ml in 0.1% Triton/PBS was added to each well for 30 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was then added and the cells incubated for 30 min. The cells were washed and substrate TMB Blue was added in 100 μl/well. Samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl/well of 1 M H2SO4. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 450 nM in an ELISA reader.

Balloon Injury and Gene Transfer.

Sprague–Dawley rats (380–450 g) were anesthetized for surgery. The common, internal, and external carotids were exposed. A 2F balloon catheter was introduced through the external carotid to reach the common carotid. The balloon was inflated with 0.2 ml of air. The inflated balloon was moved back and forth four times and then removed. The injured common carotid was washed with saline. The recombinant adenovirus [2.5 × 109 plaque-forming units (pfu)] was introduced in 100 μl of saline by using 25 gauge cannula. To prevent leakage a loose tie was placed around the inserted angiocatheter to prevent viral leakage. The common carotid was exposed to the adenovirus-containing solution for 20 min. The adenovirus solutions were then removed and the common carotid was washed with saline. The external carotid was tied and blood flow was reestablished through the common carotid. The exposed arteries were then reconnected, and the animals were sutured and allowed to recover from surgery. All animal experiments used protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee. Animals were treated humanely at all times and care was taken to reduce pain after surgery.

Isolation of Carotid Arteries.

Animals were anesthetized before killing. The animals were perfused with 250 ml of PBS, until all blood was drained, and then with 250 ml of either 4% paraformaldehyde or 2% paraformaldehyde/0.02% glutaraldehyde as required for the various staining procedures.

Immunohistochemistry.

Carotid arteries were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight immediately after dissection. Twenty-four hr later the arteries were removed from the 4% paraformaldehyde solution and placed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate in PBS for 24 h. The arteries were then placed in a tissue processor overnight, embedded, and cut. Sections were deparaffinized with xylenes, ethanol, and H2O. The sections were then placed in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min, removed, and blocked in 2% ovalbumin for 30 min. After blocking, the sections were incubated with the anti-phospho-MAPK antibody (1:200 dilution) to visualize the activated MAPK, at 37°C for 1 h. The sections were then washed in PBS and exposed to peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Biogenics) at 37°C for 10 min. Secondary antibody was removed by washing the sections in PBS. Sections were then exposed to diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 10 min. Excess DAB was removed by washing the sections with water. Hematoxilin was used as a counter stain.

Morphometery.

Samples were cut from paraffin-embedded segments. Five to ten sections, 10 μm thick, were cut at 50 μm intervals and mounted on slides and stained by using Masson trichrome. Sections with the most injury were selected for analysis. Sections were then scanned and the images collected in Adobe photoshop. An outline of the neointima, media, and adventia was drawn for each section in image proplus and areas of the various arterial regions for each sample were calculated. To avoid experimental bias, all adenovirus infusions were coded and the animals and slides processed in a blinded fashion. Samples were decoded only after final staining or neointima to media ratios were calculated.

Statistical Analysis.

Most experiments were replicated at least three times except the phospho-MAPK staining of arterial sections, which was repeated twice. Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical differences between groups were tested by ANOVA with the post hoc Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test.

Results

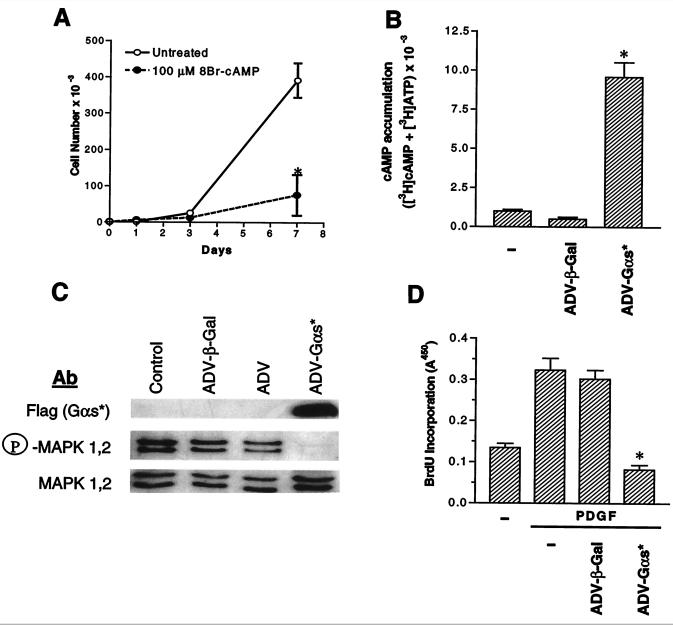

Studies by Indolfi et al. (5) had shown that 8Br-cAMP inhibited the proliferation of VSMCs in culture. We were able to observe the same effects (Fig. 1A). Because our goal was to determine whether interactions between signaling pathways could regulate proliferation in vivo, and whether such interactions could be used for therapeutic advantage, we decided to elevate cAMP by expression of the GTPase-deficient Q227L-Gαs, which is constitutively activated (18). Expression of ADV-αs* resulted in a marked increase in cellular cAMP levels in rat VSMCs in culture, under conditions where infection with ADV-β-gal had no effect on cAMP levels (Fig. 1B). Elevation of cAMP levels results in an inhibition of signal flow through the MAPK pathway (3, 6), at least in cells that express c-Raf; hence, we determined whether expression of ADV-αs* resulted in inhibition of PDGF-stimulated MAPK-1,2 activity. For this, serum-starved VSMCs were stimulated with PDGF and the activity of MAPK was assessed by blotting with antibodies that specifically detect phospho-MAPK-1,2. PDGF stimulated MAPK activity in VSMCs and this stimulation was nearly fully inhibited by infection with ADV-αs*. Infection with ADV-β-gal did not affect PDGF stimulation of MAPK activity (Fig. 1C). Growth factor stimulation of MAPK activity has been shown to trigger entry into the cell cycle in fibroblasts (19). Because expression of ADV-αs* blocked PDGF-stimulated MAPK activity, we wanted to determine whether it also inhibited PDGF-stimulated DNA synthesis, as measured by incorporation of BrdU. PDGF-stimulated DNA synthesis was inhibited by infection with ADV-αs*, but not ADV-β-gal (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Regulation of proliferation of rat VSMCs in culture. (A) Cells were treated in the presence and absence of 100 μM 8Br-cAMP in culture medium. On indicated days, cells were counted in triplicate (*, P < 0.05 8Br-cAMP-treated cells vs. untreated cells; ANOVA). (B) Subconfluent cells were infected with ADV-β-gal or ADV-αs* at 200 moi. Uninfected cells were used as controls. Cells were labeled with [3H]adenine and basal cAMP levels were measured. Values are mean ± SE of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.05 ADV-αs* vs. untreated and ADV-β-gal-infected cells; ANOVA). (C) Immunoblotting of total and phospho-MAPK in control and recombinant ADV-infected cells. Subconfluent VSMCs were transduced with either ADV-β-gal, ADV without insert (ADV), or ADV-αs*. Forty-eight hours after infection, cells were serum-starved for 24 h. Cells were then stimulated with 10 ng/ml PDGF for 30 min and lysed. Cell lysate was resolved by 10% SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose paper, and blotted with the indicated antibodies according to procedures described in refs. 8 and 15. (D) DNA synthesis as measured by BrdU incorporation in cells infected with recombinant adenovirus. Values are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations (*, P < 0.05 PDGF-ADV-αs*-treated cells vs. control and ADV-β-gal-treated cells following PDGF treatment; ANOVA).

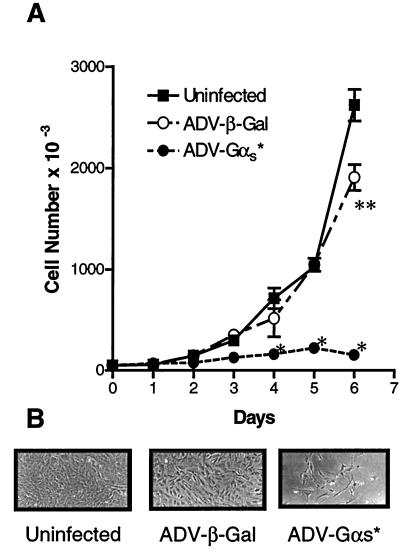

The experiments in Fig. 1 indicate that expression of αs* by infection with adenovirus would suppress the proliferation of VSMCs. We next tested whether ADV-directed expression of αs* specifically inhibited the proliferation of VSMCs. For this, uninfected as well as ADV-β-gal- and ADV-αs*-infected cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and aliquots of cells were counted every day. Under conditions where the control and ADV-β-gal-infected cells proliferate, the ADV-αs*-infected cells stop proliferating. By day 4 there were significant differences between the αs* expressing the cells and the control cells (Fig. 2). These results with VSMCs in culture suggest that expression of αs* in vivo could block proliferation as well.

Figure 2.

Effect of infection of rat VSMCs in culture by recombinant adenovirus. (A) Subconfluent (104) rat VSMCs were infected with ADV-β-gal or ADV-α s* at a moi of 200. Uninfected cells were used as controls. Initial infections were conducted in 6-well plates (for early measurements), as well as 10-cm plates (for later measurements). After infection, cells were counted in triplicate every day for 6 days. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (*, P < 0.05 ADV-αs*-treated cells vs. control and ADV-β-gal-treated cells; **, P < 0.05 ADV-β-gal-treated cells vs. unifected control and ADV-αs* cells; ANOVA). (B) Phase contrast pictures (×100) taken on day 6 are also shown.

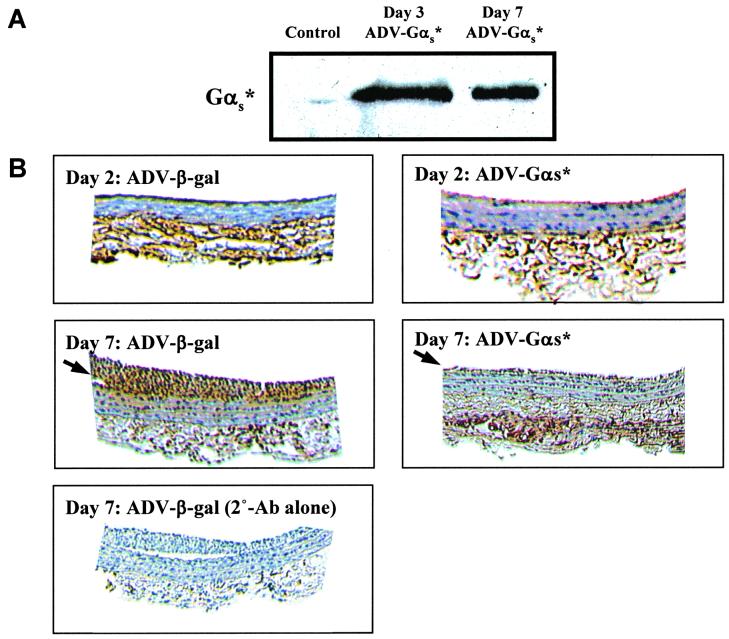

Injury to vessel wall by balloon catheters results in denuding of the endothelium, and the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells, resulting in formation of a neointima (11). We determined whether adenovirus-directed expression of αs* resulted in inhibition of neointima formation induced by balloon injury of the carotid. To determine the expression of αs*, we initially stained sections of the injured artery with an antibody against the FLAG epitope. We were unable to see reproducible staining by immunohistochemical studies. Hence, we determined expression of αs* by immunoblotting. To accomplish this, arterial sections were homogenized and resolved by SDS/PAGE and blotted with the FLAG antibody. Expression of αs* was observed in arteries 2 days after infection and persisted on day 7 (Fig. 3A). Because proliferation of VSMCs should be preceded by an increase in proliferative signal, we determined whether we could observe differences in the extent of MAPK-1,2 activation in injured animals treated with ADV-β-gal vs. ADV-αs*. To accomplish this, the carotid arteries were stained 7 days after surgery with the phospho-MAPK antibodies that recognize the activated state of MAPK-1,2 by using DAB as the chromogen to yield a dark brown reaction product. Under conditions where the neointimal sections were ADV-β-gal-treated arteries stained quite extensively for phospho-MAPK, much reduced staining was observed in the sections from ADV-αs*-treated animals (arrows). When the primary antibody against phospho-MAPK-1,2 was omitted, no staining was seen in sections from the ADV-β-gal animals (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of activated Gαs expression on the MAPK activity in the carotid artery segments. (A) Immunoblot of injured carotid artery segments from control (uninfected) and αs*-infected animals. Arterial segments were homogenized in sample buffer and an equivalent amount of proteins from each sample was resolved by SDS-gel electrophoresis and blotted with the anti-FLAG m2 antibody. The 42 KDa region is shown. (B) Visualization of phospho-MAPK in the neointima of carotid arteries. Animals were subjected to balloon angioplasty and then infused with either ADV-β-gal or ADV-αs*. After 2 or 7 days, animals were killed, the carotid arteries excised, sectioned, and stained with phospho-MAPK antibody by using DAB as the chromogen (Top and Middle). As control, sections from ADV-β-gal-treated animals were stained without primary antibody (Bottom). Arrows indicate neointimal immunoreactivity.

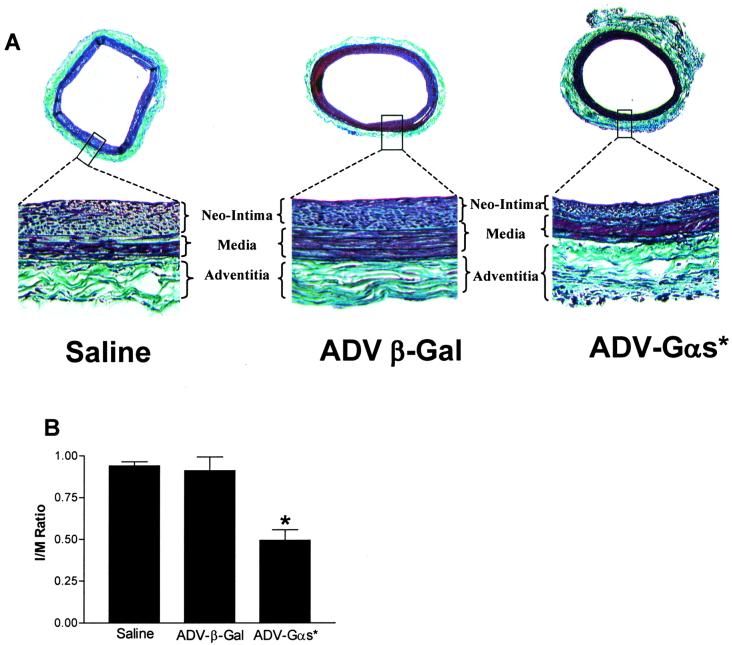

To measure neointima formation, animals were killed on day 14 and the arterial sections were analyzed. Significant neointima formation was observed in all three groups of animals (Fig. 4 A Upper). Ratios of neointima to media were plotted (Fig. 4B). When ADV-β-gal infused animals (n = 16) were compared with saline-injected animals (n = 5), no significant change in the ratio of neointima to media was seen (Fig. 4 A Lower). In contrast, sections from ADV-αs*-infused animals (n = 23) showed a significant reduction in neointima formation in the ADV-αs*-treated animals (Fig. 4B). When ratios of neointima to media were calculated, there was a 50% reduction in the ratio for ADV-αs*-treated animals as compared with ADV-β-gal-treated animals. This inhibition of neointima formation was significant (P < 0.05) using an ANOVA. The decrease in neointima/media ratio was due to a decrease in neointimal area in the αs*-treated animals (0.063 ± 0.008 mm2 for αs*-treated vs. 0.111 ± 0.011 mm2 for the β-gal-treated animals). In contrast there was no change in medial area (0.129 ± 0.005 mm2 for αs*-treated vs. 0.124 ± 0.007 mm2 for the β-gal-treated animals), nor was there a change in the total area.

Figure 4.

Neointima formation in carotid arteries of rat subjected to balloon angioplasty and treated with saline (n = 5), ADV-β-gal (n = 16), or ADV-αs* (n = 23). (A Upper) Typical stained cross sections (×25). (A Lower) Enlargement of each boxed region (×100). (B) Neointima to media ratio for the three groups are shown. Values are mean ± SE of the indicated number of animals in each group (*, P < 0.05 ADV-αs*-treated cells vs. control and ADV-β-gal-treated cells; ANOVA)

Discussion

A balance of positive and negative signals regulates complex physiological responses such as proliferation. It has become well established that signaling through MAPK-1,2 is in large part responsible for the triggering of proliferative responses in many cell types. The MAPK pathway can be influenced both positively and negatively by several upstream signals. These include signals from receptor tyrosine kinases, as well as nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that activate Ras. Additionally, Ca2+-mobilizing receptors that activate phospholipase-C use protein kinase C to directly activate Raf. A large number of G protein coupled receptors signal through Gβγ subunits to activate MAPK-1,2, and are thus thought to trigger proliferation. It has been recently suggested that Gβγ subunits may mediate the bulk of the proliferative signals originating from serum for VSMCs (20). Irrespective of the origins of these proliferative signals, their routing through the c-Raf to MAPK-1,2 protein kinase cascade affords an opportunity to modulate signal flow through this pathway. Protein kinase A has been shown to phosphorylate c-Raf at multiple sites, and thus, impair its ability to interact with Ras (21), as well as its ability to phosphorylate and activate MEK-1,2 (6). This results in decreased activation of MAPK-1,2. The data in this paper show that expression of a constitutively activated Gαs results in an increase in the basal levels of cAMP in VSMCs. This increase is accompanied by a decrease in the stimulation of MAPK by proliferative agents both in culture and in vivo. This inhibition is not complete and, hence, it was not predictable whether the inhibition would translate into reduced proliferation. Both in-culture and in vivo expression of activated Gαs results in the inhibition of VSMC proliferation. Thus, it appears most likely that the reduction of MAPK activity is associated with decreased proliferation of VSMCs in vivo. Dominant-negative MEK-1 has been shown to inhibit neointima formation (22). Thus, the data presented here suggest that interactions between signaling pathways can regulate proliferation in vivo, and that such regulation could serve as the basis for therapeutic intervention for pathologic states arising from proliferative disorders.

Our studies also demonstrate the potential usage of G protein α-subunits themselves as therapeutic agents. G protein α-subunits possess the capability to be constitutively activated to varying levels by mutating key residues in their GTPase domains (23). This results in a constitutive activation of the second messenger pathway. Expression of constitutively activated Gαs can be deleterious in certain cell types. In fact, certain subsets of pituitary tumors are thought to maintain their transformed phenotype because of the expression of activated Gαs (24). In contrast, in other cells, such as the VSMCs used in this study, and in the human breast cancer cells (8), expression of Gαs suppresses proliferation and, thus, has therapeutic potential for proliferative disorders. At least two vascular disorders result, in part, from smooth muscle cell proliferation: Vein graft failure and restenosis after balloon angioplasty. In these cases the targeted expression of activated forms of Gαs could be therapeutically useful. Whether the conclusions reached in studies from animal models can be extrapolated to humans remains to be experimentally determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Veronica Gulle and Ms. Ameera Ali for technical assistance and Dr. Moshe Shelev and members of the Mount Sinai Animal Facility for their assistance in postsurgical care for the animals. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-54508 and CA-81050 (to R.I.) and HL 54469 (to J.T.F. and M.B.T.). W.H. was supported by a minority predoctoral training supplement to DK-38761. G.P.B. was supported by National Research Service Award (GM-18887).

Abbreviations

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- moi

multiplicity of infection

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- ADV

adenovirus

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- BrdU

5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

References

- 1.Davis R J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14553–14556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan S E, Weinberg R A. Nature (London) 1993;365:781–783. doi: 10.1038/365781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves L M, Bornfeldt K E, Raines E W, Potts B C, Macdonald S G, Ross R, Krebs E G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10300–10304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastan I H, Johnson G S, Anderson W B. Ann Rev of Biochem. 1975;44:491–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.002423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indolfi C, Avvedimento E V, Di Lorenzo E, Esposito G, Rapacciuolo A, Giuliano P, Grieco D, Cavuto L, Stingone A M, Ciullo I, et al. Nat Med. 1997;3:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafner S, Adler H S, Mischak H, Janosch P, Heidecker G, Wolfman A, Pippig S, Lohse M, Ueffing M, Kolch W. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6696–6703. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J-C, Iyengar R. Science. 1994;263:1278–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.8122111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J-h, Bander J, Santore T, Chen Y, Smit M J, Iyengar R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;94:2648–2652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruntzig A R, Senning A, Siegenthaler W E. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197907123010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Block P C. Circulation. 1985;72:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride W, Lange R A, Hillis L D. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1734–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feurestein G Z. In: Coronary Restenosis. Feurestein G Z, editor. New York: Dekker; 1997. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fingerle J, Johnson R, Clowes A W, Majesky M W, Reidy M A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8412–8416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santore, T. A. & Iyengar, R. (2001) Methods Enzymol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Smit M J, Verzijl D, Iyengar R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15084–15089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothman A, Kulik T J, Taubman M B, Berk B C, Smith C W, Nadal-Ginard B. Circulation. 1992;86:1977–1986. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Iyengar R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12253–12256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masters S B, Miller R T, Chi M H, Chang F H, Beiderman B, Lopez N G, Bourne H R. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15467–15474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albanese C, Johnson J, Watanabe G, Eklund N, Vu D, Arnold A, Pestell R G. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23589–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iaccarino G, Smithwick L A, Lefkowitz R J, Koch W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3945–3950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Dent P, Jelinek T, Wolfman A, Weber M J, Sturgill T W. Science. 1993;262:1065–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.7694366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Indolfi C, Avvedimento E V, Rapacciuolo A, Esposito G, Di Lorenzo E, Leccia A, Pisani A, Chieffo A, Coppola A, Chiariello M. Basic Res Cardiol. 1997;92:378–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00796211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourne H R, Sanders D A, McCormick F. Nature (London) 1991;349:117–127. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis C A, Masters S B, Spada A, Pace A M, Bourne H R, Vallar L. Nature (London) 1989;340:692–696. doi: 10.1038/340692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue T-L, Wang X K, Stadel J M, Feurestein G Z. In: Coronary Restenosis. Feurestein G Z, editor. New York: Dekker; 1997. pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]