Abstract

Streptoccocus pneumoniae infection can result in local and systemic diseases such as otitis media, pneumonia and meningitis. Sensorineural hearing loss associated with this infection is mediated by the release of an exotoxin, pneumolysin. The goal of the present study was to characterize the mechanisms of pneumolysin toxicity in cochlear hair cells in vitro. Pneumolysin induced severe damage in cochlear hair cells, ranging from stereocilia disorganization to total cell loss. Surprisingly, pneumolysin-induced cell death preferentially targeted inner hair cells. Pneumolysin triggered in vitro cell death by an influx of calcium. Extracellular calcium appeared to enter the cell through a pore formed by the toxin. Buffering intracellular calcium with BAPTA improved hair cell survival. The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway involved in pneumolysin-induced cell death was demonstrated by the use of bongkrekic acid. Binding of pneumolysin to the hair cell plasma membrane was required to induce cell death. Increasing external calcium reduced cell toxicity by preventing the binding of pneumolysin to hair cell membranes. These results showed the significant role of calcium both in triggering pneumolysin-induced hair cell apoptosis and in preventing the toxin from binding to its cellular target.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), a Gram positive bacterium, is a major human pathogen involved in several pathologies such as pneumonia, otitis media and meningitis (Alonso de Velasco et al. 1995). The bacterial pathogenicity of streptococcus pneumonia is determined by both host responses to its polysaccharide capsule and by pneumococcal proteins (Paton et al. 1993; Tuomanen et al. 1995). Pneumococcus produces a wide range of toxic factors (cell wall components, surface-associated and secreted toxins) that can contribute to its virulence (Alonso de Velasco et al. 1995; Novak et al. 2000).

Pneumococcal meningitis remains a serious disease with a high morbidity and mortality. Up to 30% of surviving patients are left with a permanent sensorineural hearing loss. Deafness associated with meningitis is probably secondary to cochlear damage (Dodge et al. 1984; Durand et al. 1993; Winter et al. 1996). Infection spreads from the subarachnoid space to the perilymphatic space of the inner ear (labyrinth) via the cochlear aqueduct (Kesser et al. 1999). A number of animal studies, based on meningogenic hearing loss, have demonstrated specific ultrastructural changes to the organ of Corti (Osborne et al. 1995; Winter et al. 1996) that were induced by the release of the exotoxin, pneumolysin (PLY) (Winter et al. 1997). This toxin is thought to be the main cause of the destruction of the hair cells of the inner ear. The underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Pneumolysin, a 53 kDa protein toxin, is a member of a large family of bacterial-protein toxins (Alouf, 2000). They are often referred as ‘cholesterol-binding toxins’ which reflects the ability of free cholesterol to inhibit their activity. In association with cell membrane cholesterol, monomers of PLY oligomerize into ring-shaped structures to form pores (Mitchell, 2000). Pneumolysin is a potent cytotoxic agent (Mitchell & Andrew, 1997) that provokes rapid neuronal cell death. Its action on neurones is well documented and mediated via multiple apoptotic pathways (Braun et al. 2001, 2002; Stringaris et al. 2002). In guinea pig cochleae, perfusion of PLY resulted in severe effects on the auditory-evoked potentials with a drastic reduction in the eight-nerve action potential, the cochlear microphonic and its distortion products (Comis et al. 1993; Skinner et al. 2004). In addition, scanning electron microscopy observations revealed hair cell (HC) stereocilia disorganization (Comis et al. 1993). The purpose of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms of action of PLY on cochlear hair cells at both the molecular and cellular level. The toxicity of PLY was assessed in vitro using rat organ of Corti (OC) cultures.

The present study shows that PLY causes preferential death to inner hair cells (IHCs) rather than outer hair cells (OHCs). Cell death is initiated by an increase in intracellular calcium caused by PLY binding to the HC membrane. Interestingly, we also show that this binding and the resulting ototoxicity can be prevented by increasing extracellular calcium.

Methods

Evaluation of the toxicity of pneumolysin on hair cells in vitro

Organ of Corti cultures

For organotypic cultures, newborn Wistar rats 2–4 days old were used. The pups were anaesthetized with a mixed solution of 1/3 xylazine (2% Rompun-Bayer, Germany) and 2/3-ketamine hydrochlorate (50 mg ml−1, Ketalar, Parke Davis, France) and decapitated. The organ of Corti (OC) (plus the spiral ganglion) was isolated in sterile conditions and the stria vascularis removed. Dissection of the OC was performed in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solution (DPBS Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA; mm: CaCl2 1, MgCl2 0.5, KCl 2.7, NaCl 137, KH2PO4 1.5, Na2HPO4 8, d-glucose 5.5, pH 7.50, 290 mosmol (kg H2O)−1). The entire OC (base to apex) was then placed in a culture medium with the following composition: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, ref.41965, Gibco, Invitrogen, France, containing (mm): glucose 25, NaHCO3 44, CaCl2 1.8) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 25 mm Hepes buffer and penicillin (2500 IU). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2–3 days. Animal handling and killing were done in accordance with the French Ministry of Agriculture and EEC regulations.

Culture treatments

Each OC explant was stabilized by culturing it for 24 h prior to treatment with PLY. Pneumolysin was purified as described (Saunders et al. 1989) and kept frozen until used. The specific activity of PLY was 1.6 × 105 hemolytic units (HU) (mg of protein)−1. The toxin was freshly prepared in culture medium and added directly to culture wells at final concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 ng μl−1 for 24 h. Control cultures were identical to treated cultures, but no toxin was added. The OCs were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2–95% air environment. At the end of the culture period (varying between 2 and 3 days), the explants were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer at 4°C.

The preventive effect of an intracellular calcium chelator on PLY toxicity was evaluated by preincubating explants for 5 or 8 h with 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy) ethane-N, N, N′,N′-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM) (50 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich) and then incubating them for an additional 24 h in the presence of both the toxin and BAPTA-AM.

The implication of apoptotic pathways in PLY toxicity was examined in OC cultures. Caspases were inhibited using the peptide inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (a general caspase inhibitor, BD Biosciences Pharmingen). The OCs were preincubated for 48 h in the presence of z-VAD-fmk (100 μm). Cultures were then incubated in the presence of both PLY and z-VAD-fmk for an additional 24 h. Bongrekic acid (20 μm; Sigma-Aldrich), a mitochondrial inhibitor, was preincubated one hour before adding PLY for 7 h. These experiments were performed on a shorter time exposure due to the toxic effect of bongkrekic acid after 24 h of culture. Both apoptotic drugs were used as described by the manufacturers and at inhibitory concentrations (Furlong et al. 1998; Dumont et al. 1999; Forge & Li, 2000; Cheng et al. 2003).

At the end of the culture period, explants were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for HC counts as described below.

Hair cell counts

The fixed explants were first permeabilized with 0.5% triton-X100 in PBS for 30 min. They were then stained with a fluorescent conjugated phalloidin (1 μg ml−1) (FITC or TRITC) (Sigma) for 45 min and finally mounted (turn by turn) as a surface preparation on a glass slide. The fluorescent images were acquired with a high resolution DXM 1200 Nikon camera mounted on an epifluorescent inverted microscope eclipse TE300 (Nikon), using an oil-immersion 60× objective (NA 1.4). The toxicity of PLY on HC was evaluated by counting the number of HCs presenting a phalloidin-labelled hair bundle on the surface of the OC. Using a double-blind protocol, hair cell counts were systematically performed on portions of OC of 140 μm width. This corresponded to an imaging acquisition field. Each acquisition field contained approximately 15 IHCs and 60 OHCs. Disorganization of stereocilia is an early sign of HC pathology, and phalloidin-labelled HCs reflected the number of living HCs (Kopke et al. 1997; Bodmer et al. 2003). HCs with a regular phalloidin-labelled hair bundle were considered undamaged or normal. HCs in the acquisition field that had disorganized stereocilia with a weak fluorescent labelling were counted as damaged or absent. To illustrate the issue of normal versus absent (or damaged) HCs, we will refer to the phalloidin-labelled explant example shown in Fig. 2d. In the row of IHCs, two cells were counted as normal and five as absent (two with disorganized stereocilia (black arrow) and three missing (open arrowheads)). In the OHC rows, 20 cells were estimated as normal and three as absent (one with a disorganized hair bundle (black arrow) and two with no hair bundle (open arrowheads)). Data were expressed in percentages (remaining phalloidin positive-HC (living or normal HCs) over the total number of cells) in a field of 140 μm width.

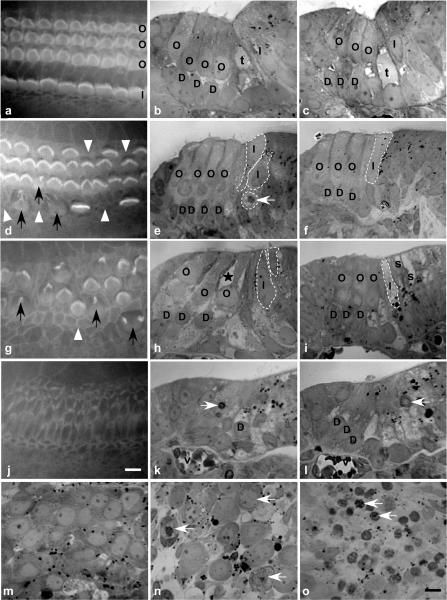

Figure 2. Cell morphological changes induced by PLY in organotypic cultures.

Cochlear explants were cultured 24 h with or without the toxin and examined in phalloidin-stained surface preparations (a, d, g, j) and semithin sections (b, c, e, f, h, i, k–o). Control explants with normal characteristics of OHCs (O) and IHCs (I) are shown in surface preparation (a) and semithin sections (b, c). At PLY 1 ng μl−1, a preferential absence or disorganization of stereocilia of IHCs is noted (d), while the majority of OHCs and Deiters' (D) cells are intact (e, f) Black arrows show HCs with a disorganized stereocilia, and open arrowheads show cells with no hair bundle. Note a tissue disorganization at the IHC level (broken lines marking cell borders) (e, f) with a loss of the tunnel of Corti (t). Apoptotic cells (white arrows) are observed. At PLY 5 ng μl−1, both IHCs and OHCs (loss and disorganization of stereocilia) are strongly affected (g, h, i). In OHCs, apoptotic features were present (shrinkage of their apical pole, presence of cytoplasmic vacuole (*)). Some IHCs were extremely damaged and some surrounding cells (s) were absent. At PLY 10 ng μl−1, no stereocilia can be observed (j). Tissue is highly disorganized with the presence of apoptotic cells (white arrows) and no recognizable HCs (k, l).Within the spiral ganglion, apoptotic neurones (eccentric nucleus, chromatin condensation, vacuoles, cell shrinkage) were observed after PLY treatment (1 ng μl−1, n; 10 ng μl−1, o) while no apoptotic cells were observed in the control explants (m). Scale bars 10 μm; v, blood vessel.

Construction of N-terminal eGFP-PLY fusion plasmid, expression, and purification of eGFP-PLY

The coding sequence of PLY was amplified with the introduction of appropriate restriction sites by PCR using primers PlyPetFwd (CCG GAT CCG GCA AAT AAA GCA GTA AAT GAC TTT; BamH1 site italicized) and PlyPetRev (GAC G GA GCT C GA CTA GTC ATT TTC TAC CTT ATC; Sac1 site italicized). The PCR product was ligated into BamHI/SacI-digested pET33b (Novagen) and transformed into TOP10 E. coli. The presence of a correctly sized insert in pET33b was confirmed by BamHI/SacI digestion followed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The GFP coding sequence was amplified from pNF320 (Freitag & Jacobs, 1999) and appropriate restriction sites introduced by PCR using primers GFPpET33bFwd (GT CAG GCT AGC ATG AGT AAA GGA GAA GAA C; Nhe1 site italicized) and GFPpET33bRev (CC ACG C AG ATC T TT GTA TAG TTC ATC C; BglII site italicized). The PCR product was cut with NheI and BglII, ligated into NheI/BamHI digested pET33bPLY and transformed into TOP10 E. coli. The plasmid was recovered and mutations F64L and S65T (Cormack et al. 1996) were introduced into GFP by site directed mutagenesis (Quikchange SDM Kit, Stratagene) using primers GFP-S65T-F64LmutaFWD (CAC TTG TCA CTA CTC TGA CTT ATG GTG TTC AAT GC) and GFP-S65T-F64LmutaREV (GCA TTG AAC ACC ATA AGT CAG AGT AGT GAC AAG TG). The sequence was confirmed and the plasmid was transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli (Stratagene).

Recombinant eGFP-PLY was expressed in Terrific Broth by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalacto-pyranoside (IPTG) induction. Cells were disrupted using a high pressure homogenizer and resuspended in PBS. Crude supernatants were purified by nickel affinity chromatography and eluted on 0–300 mm imidazole concentration gradient. Fractions containing purified eGFP-PLY were dialysed against a greater than 50-fold volume of PBS three times at 4°C.

Semithin sections

Organotypic cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB). The explants were washed, postfixed for 1 h in 1% OsO4, incubated in aqueous uranyl acetate (1%), dehydrated in gradient of ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin (Sigma chemicals). Semithin sections (1 μm) were obtained using an LKB ultramicrotome. Sections were stained with 0.5–1% toluidine blue in saturated borate, and mounted for light microscopic observation. Semithin sections of OC explants were used in order to follow the HC morphological changes induced by PLY treatment.

Localization of pneumolysin in hair cells

Immunolocalization of PLY was conducted on surface preparations of organotypic OC cultures. The rabbit antipneumolysin antibody was produced and provided by Mitchell, its specificity having been previously demonstrated (Mitchell et al. 1988). The explants were incubated with the primary antibodies (dilution 1: 150) overnight at room temperature. They were then washed in PB solution and incubated with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (dilution 1: 250; Sigma) for 2.5 h. Explants were rinsed and mounted for epifluorescence. All incubations were performed in the presence of 0.1% triton X-100.

A recombinant form of PLY, coupled to a green fluorescent protein (eGFP-PLY), was used to determine the localization of the toxin in HCs (in freshly dissociated cells). Fluorescent images were acquired (with the same camera settings) as described above, and fluorescence intensity was evaluated using Scion-image software (Scion corporation).

Cell death detection

Detection of apoptotic cell death was undertaken on fixed OC cultures by using an in situ cell death TUNEL detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Staining was achieved as described by the manufacturer. Necrotic cells were detected by determining cell membrane integrity using the vital dye propidium iodide (PI). After treatment with PLY, propidium iodide (10 μg ml−1) was added to the culture medium and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. A double staining with phalloidin (TRITC or FITC) was performed as described above to facilitate the counting of HCs.

Calcium measurement in isolated cochlear hair cells

Increases in intracellular calcium in response to PLY application on isolated HCs was monitored using the calcium probe indo-1-AM (Molecular Probes). Experiments were conducted in Wistar rats, ranging in age from postnatal day P16 to P18. HCs are easier to isolate and recognize in these circumstances. It has to be noted that mature HCs are also affected by PLY (Comis et al. 1993; Skinner et al. 2004) and we assume that the toxin acts through a similar mechanism in young and mature HCs.

The OC was isolated as described above. The OC was then pretreated with trypsin (0.1 mg ml−1) for 10–15 min at room temperature. A mechanical dissociation (with a pipette flow) on a glass coverslip, in a 100 μl drop of DPBS, was used to produce isolated HCs. Intracellular calcium variation was monitored by dual emission microspectrofluorometry at 405 nm and 480 nm using indo-1-AM (Dulon et al. 1991). The system consisted of a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope fitted with two photometers (P1, Nikon). The fluorescence signals were measured in a slit (150 × 150 μm) centred on the cell. The two emission signals were divided online giving the emission fluorescence ratio (ratio of fluorescence at 405 and 480 nm, F405/F480 nm) which was recorded using Axotape software (sampling rate at 150 Hz). Data were expressed as a ratio of fluorescence. Only those cells that were well attached to the glass coverslips were used. Pneumolysin was applied locally to isolated HCs through a Picospritzer puffer system (Picospritzer II, General Valve, Fairfield, NJ, USA). Application glass pipettes were positioned 20–30 μm from the cell body of HCs.

Rat hippocampal neurones

Hippocampal cells were prepared from 18-day-old rat embryos according to the method of Goslin and Banker (1991). Briefly, the rat pups were quickly decapitated and their brains removed from the skull. The hippocampi were dissociated by trypsin and mechanical treatment, plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips at a density of 9500 cells cm−2, and maintained in a serum-free medium (N2 medium) suspended above a glia feeder layer. Adding 5 mm cytosine arabinoside prevented proliferation of non-neuronal cells. All experiments were performed in cells kept for 10 days in culture.

Data analysis

All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). In order to determine the toxicity of PLY, the mean dose–response curve was fitted with a Hill equation using GraphPad Prism. The equation was Y= 1/(1 + (EC50/X))nH where EC50 is the concentration of PLY that gives a loss of 50% of HCs, X the PLY concentration and nH the Hill coefficient.

To compare the action of a drug on PLY toxicity (at one concentration), we expressed the data as a percentage of protection. The level of protection of a drug on PLY toxicity was estimated by using the following equation: [(B−A)/100 − A]× 100, where A is the percentage HC in control condition (PLY alone) and B is the percentage HC in the treated explants (drug + PLY). A protective effect of 100% (full protection) meant no HC loss (B= 100%), while no protection (0%) corresponded to no change in HC loss in the presence or absence of a drug (B=A).

Results

Toxicity induced by pneumolysin in cochlear hair cells

The toxicity of pneumolysin (PLY) on cochlear HCs was studied on organ of Corti (OC) cultures and assessed by counting OHCs and IHCs presenting a normal stained phalloidin-FITC hair bundle (Fig. 1). Phalloidin is well known to bind specifically to F-actin which is the major component of stereocilia. Figure 2a, d, g and j) illustrates hair bundles stained with phalloidin-FITC in control and PLY-treated cultures. Control OC cultures showed a characteristic arrangement of HCs with the presence of three rows of OHCs and one row of IHCs (Fig. 2a). The PLY-treated organs (24 h exposure) showed a dose-dependent injury to the HC stereocilia progressing from hair bundle disorganization (Fig. 2d and g) to complete cell loss (Fig. 2j). The percentage of phalloidin-stained HCs (OHCs versus IHCs) was plotted as a function of the PLY concentration and showed that PLY toxicity was clearly dose dependent (Fig. 1A). In addition, PLY at low concentrations (0.1 and 1 ng μl−1) preferentially affected IHCs. The phalloidin staining for a PLY concentration of 1 ng μl−1 showed that most stereocilia were absent or highly disorganized in IHCs, while they appeared normal in OHCs (Fig. 2d). Total HC loss was observed for PLY concentrations higher than 10 ng μl−1. Moreover, at this concentration, hair bundles were completely absent and phalloidin staining revealed scars at the surface of the epithelium (Fig. 2j).

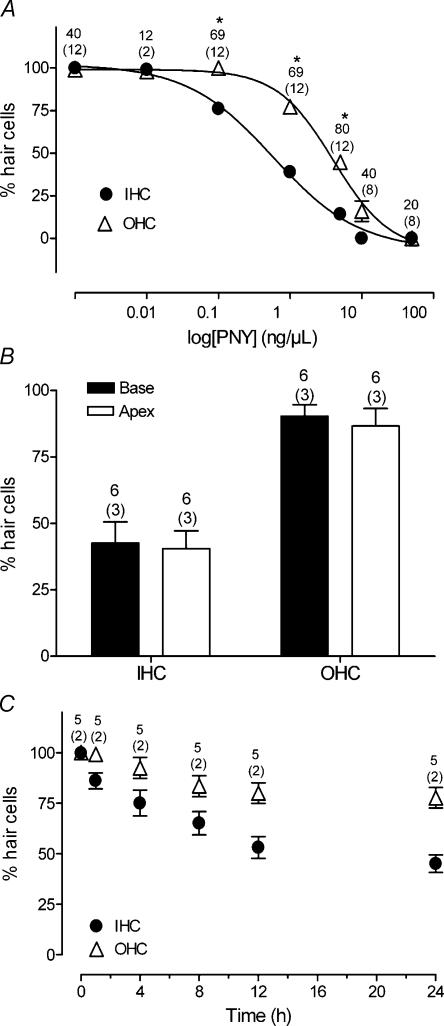

Figure 1. Dose-dependent toxicity of pneumolysin on cochlear HC in organotypic cultures.

A, dose-dependent toxicity of PLY on IHC versus OHC. The percentage of phalloidin-stained HCs (with a normal hair bundle) was expressed as a function of the concentration of PLY (24 h exposure). The curves were fitted with a Hill equation and parameters were: EC50= 0.6; 4 ng μl−1 and Hill slope 0.7; 1.1 for IHC and OHC, respectively. IHCs were preferentially affected by PLY. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant different loss between IHC and OHC at the same concentration (unpaired t test, P < 0.001). B, comparison of PLY toxicity on HCs isolated from the base or the apex of the OC. C, PLY toxicity as a function of the duration of toxin (1 ng μl−1) exposure. Counts were summed across the numbers of OC explants mentioned in parenthesis. The number of fields used to determine the average of phalloidin-stained HCs corresponds to the upper numbers. Error bars show s.e.

The dose–response curve in Fig. 1A was fitted with a Hill equation and the resulting parameters were 0.6 and 4 ng μl−1 for EC50, with Hill slopes of 0.7 and 1.1 for IHCs and OHCs, respectively. The IHCs were more sensitive to PLY than OHCs (∼6.6 times at the EC50 concentration). We also verified that PLY affected the three rows of OHCs similarly (not shown). In addition, the PLY toxicity was comparable for HCs isolated from the base or the apex of the OC (Fig. 1B). The PLY toxicity occurred rapidly since HC damage was first observed within an hour of toxin exposure (1 ng μl−1) (Fig. 1C). The PLY toxicity affected IHCs preferentially and increased with the duration of toxin treatment.

The morphological HC changes induced by PLY were examined on semithin sections of cultured OC. The HC morphology was normal in control cultures (Fig. 2b and c). In some areas, HC stereocilia were not observed because the plane of section missed them. Explants treated with PLY 1 ng μl−1 for 24 h showed different signs of OC damage, with pathology more focused on IHCs (Fig. 2e and f). Some IHCs were abnormally located beneath the apical surface of the epithelium, and others presented apoptotic signs of cell death such as chromatin condensation. The tunnel of Corti was systematically absent, reflecting tissue disorganization and damage to pillar cells. At this concentration, the OHCs and Deiters' cells, however, showed relatively normal morphology as in control explants. These observations were consistent with the results from phalloidin staining (Fig. 2d). Again, there was a prominent effect on IHCs. At the mid-range concentrations of PLY (5 ng μl−1), the toxic effect was more pronounced, and damage was now seen in both IHCs and OHCs. The OHCs showed signs of cell shrinkage and contained numerous cytoplasmic vacuoles. These were expected characteristics of apoptosis (Fig. 2h and i). Nevertheless, these features were more pronounced in IHCs. Some IHCs were absent from the explant, and others were severely damaged. At high PLY concentration (10 ng μl−1), semithin sections showed a highly disorganized tissue and a reduction in the thickness of the epithelium. Numerous apoptotic cells (mostly supporting cells) were present, and HCs were completely absent (Fig. 2k and l).

In all PLY-treated explants, necrotic characteristics were not present (i.e. absence of swollen cells, swollen nuclei, or organelles outside organized cells (as a sign of a cytoplasmic membrane disruption)). In addition, we observed the effect of PLY on the spiral ganglion neurones, which were attached to the cultured OC. In PLY-treated spiral ganglion, all apoptotic neurones showed clear chromatin condensation and cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 2n and o). At high PLY concentrations, the tissue contained only apoptotic neurones (as confirmed by shrunken cell bodies and chromatin condensation) throughout the spiral ganglion.

In the following sections of the study, the in vitro molecular pathway of HC death was characterized using a PLY concentration of 1 ng μl−1. At this low range, PLY preferentially damaged IHCs (see above) and had little effect on OHCs.

Localization of pneumolysin in cochlear hair cells

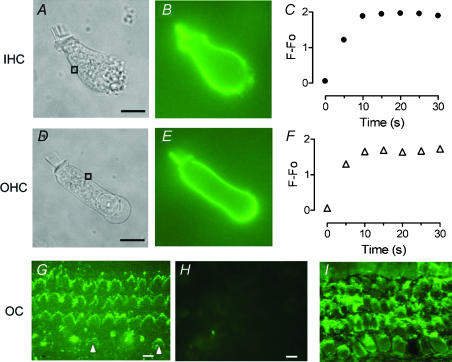

Pneumolysin is often described as a ‘cholesterol-binding toxin’, to reflect the fact that its ability to damage cell membranes depends on binding to cholesterol. In the previous paragraph, we described a severe toxic effect of PLY on cochlear HC. There was a different degree of action between IHCs and OHCs. To determine if this difference was related to a different binding of the toxin on the two HC populations, the distribution of PLY binding between IHCs and OHCs was examined using a toxin coupled to a fluorescent conjugate (eGFP-PLY). We first verified the toxic property of the recombinant eGFP-PLY in our OC culture model. The eGFP-PLY induced similar HC toxicity as the wild-type form of PLY. For an eGFP-PLY concentration of 1 ng μl−1 (24 h), the percentage of phalloidin-stained HC was 46.0 ± 4.0% and 73.5 ± 2.7% of IHC and OHC, respectively. The eGFP-PLY toxicity also showed a preferential sensitivity of the toxin to IHC in comparison to OHC. In organotypic cultures, eGFP-PLY labelled the hair bundles of both IHC and OHC (Fig. 3G), with staining more pronounced in OHCs than in IHCs. The lighter staining of the IHC hair bundle is probably a consequence of high disorganization. Most stereocilia were absent or disorganized in IHCs while they appeared normal in OHCs. To determine more precisely the distribution of PLY binding on cochlear HCs, we applied eGFP-PLY (5 ng μl−1) to freshly dissociated HCs with a 2 s-puff period. Figure 3B and E) illustrates the fluorescent labelling observed in isolated IHCs and OHCs. The labelled toxin was distributed homogeneously in the plasma membrane, in the cuticular plate and in the stereocilia. Moreover, the binding of eGFP-PLY to the cell membrane occurred rapidly. Fluorescence was first detected during the 2-s-application and reached a maximum ∼10–20 s after the puff (Fig. 3C and F). The eGFP-PLY was restricted to the surface membrane and no fluorescence was detected inside the cytosol. In addition, the membranous staining was not reversible over a period of 15 min observation. Finally, the toxin distribution was comparable in IHCs and OHCs, and no significant difference in fluorescence intensity could be observed. This same toxin distribution in HCs was confirmed using a longer eGFP-PLY puff-application (20 s) and a different toxin concentration (1 ng μl−1 or 10 ng μl−1). Immunostaining with a PLY-specific antibody, on treated OC cultures (PLY 1 ng μl−1), showed the presence of PLY protein in the HC region (Fig. 3I). The distribution of PLY appeared the same in both IHCs and OHCs.

Figure 3. Binding of PLY in cochlear HCs.

The eGFP-PLY (5 ng μl−1) was pressure puffed for 2 s on isolated rat HCs. An example of an IHC (A) and OHC (D) is shown in brightfield. Fluorescent images (B, E) were obtained 10 s after the puff of PLY on the same cell (A, D). The eGFP-PLY labelling was localized in the plasma membrane of IHCs and OHCs. Graphs (C,F) show the time course of the incorporation of eGFP-PLY in the HC plasma membrane. The fluorescence intensity was quantified by integration of a small zone shown by the rectangular box shown on the brightfield images. Fluorescence (F−F0) is corrected from background fluorescence (F0). G, binding of eGFP-PLY in OC cultures (representative of four explants) treated 24 h with 1 ng μl−1 of the conjugated-toxin. A more sustained labelling in OHCs' hair bundles compared to IHCs' (arrowhead) could be observed. Note a high disorganization of the IHC stereocilia when remaining. H, I, immunolocalization of PLY in control (H) and PLY (I) (1 ng μl−1, 24 h) -treated OC cultures (representative of three explants). Surface preparation of the OC showed a staining of sterocilia and plasma membrane of IHCs and OHCs, while no labelling was observed in control cultures. Scale bars 10 μm.

Molecular mechanisms of hair cell death: the role of calcium

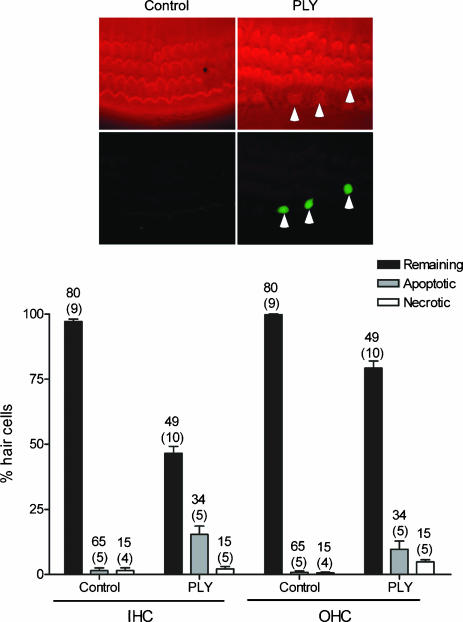

The participation of apoptosis in HC destruction, after PLY treatment, was determined in vitro using a TUNEL reaction, a marker of DNA fragmentation. Necrotic processes were detected by determining HC membrane integrity using propidium iodide (PI). PI is excluded by those cells with an intact cytoplasmic membrane. The OC cultures were treated with 1 ng μl−1 for 24 h and then double stained with phalloidin in order to visualize HCs. The PLY-induced apoptosis was observed in both IHCs and OHCs while little necrosis was detected (Fig. 4). In control conditions, where there was an absence of toxin, only low numbers of apoptotic or necrotic HCs were found. The amount of apoptotic HCs in treated cultures was unexpectedly low among the two HC types. Fifteen per cent of total IHCs and 8% of all OHCs showed DNA fragmentation after 24 h of PLY treatment. The quality of the TUNEL labelling was verified by running an internal positive control as described by the manufacturer (DNase I treatment). In additional experiments (not shown), we observed a similar amount of apoptotic HC (TUNEL positive) after treatment with 1 or 5 ng μl−1 of PLY.

Figure 4. PLY-induced apoptosis in HC.

Apoptotic and necrotic HC are detected by staining for a TUNEL reaction or with propidium iodide, respectively. Cell death labelling is performed in OC culture 24 h in the absence (control) or presence of PLY 1 ng μl−1. The bars show the percentage of remaining, apoptotic and necrotic IHCs and OHCs. The PLY induced apoptotic cell death in both IHCs and OHCs and minor necrosis. Images illustrate OC cultures labelled with a TRITC-phalloidin (top) and TUNEL reaction (bottom). Arrowheads shows TUNEL-positive HCs. Counts were summed across the numbers of explants mentioned in parenthesis and the number of fields used is indicated by the upper numbers. Error bars show s.e.

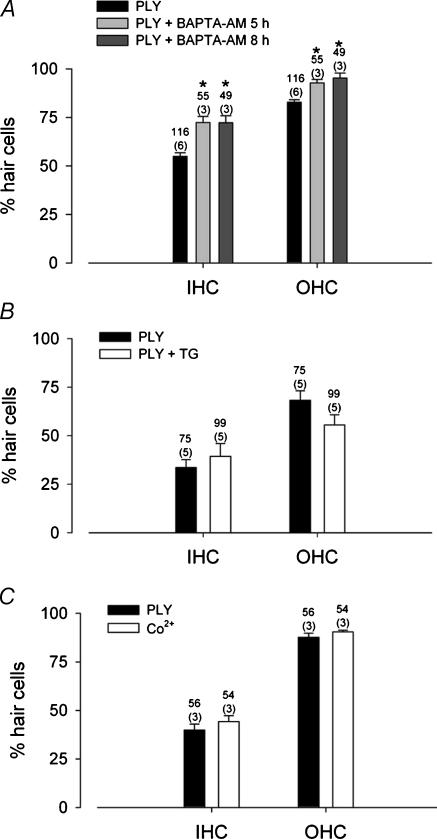

Calcium influx or internal calcium release have been shown to participate in cell death mechanisms in various systems (Xu et al. 2001; Orrenius et al. 2003) including hair cells (Matsui et al. 2004). We therefore evaluated whether intracellular calcium played a role in PLY toxicity. Organotypic cultures were incubated with BAPTA-AM, a cell-permeant calcium chelator, for 5 or 8 h before adding the exotoxin (1 ng μl−1) to the culture medium for an additional 24 h. We first verified a non-toxic effect of BAPTA-AM on HCs in organotypic cultures (data not shown). Buffering of intracellular calcium significantly prevented PLY toxicity (unpaired t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). The decrease in PLY toxicity was observed for both IHCs and OHCs. These data revealed a significant role for changes in intracellular calcium levels in the cytotoxic effect of PLY. The protective effect of BAPTA-AM was apparently more pronounced for OHCs than IHCs, with a level of protection (BAPTA-AM 8 h) estimated at 38% and 73% for IHCs and OHCs, respectively. However, considering the differential effect of PLY on IHC and OHC, it was difficult to compare the level of protection in these cells.

Figure 5. PLY toxicity is mediated by calcium.

A, intracellular buffering of calcium with BAPTA-AM reduced PLY-induced HC death. Cultures were pretreated with BAPTA-AM 5 or 8 h prior to incubation with PLY (1 ng μl−1). Data represent the number of phalloidin-labelled HCs after 24 h of incubation in PLY in the presence or absence of the calcium chelator. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (unpaired t test, P < 0.001). B, thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of intracellular calcium store, did not prevent PLY toxicity. The histogram shows the number of phalloidin-labelled HCs after 24 h incubation of PLY in the presence or absence of TG (50 μm). C, PLY-induced HC death was not blocked by an inhibitor of voltage-dependent channels. Cobalt (50 μm) had no effect on PLY toxicity. Counts were summed across the number of OCs mentioned in parenthesis. The numbers of counted fields correspond to the upper numbers. Error bars show s.e.

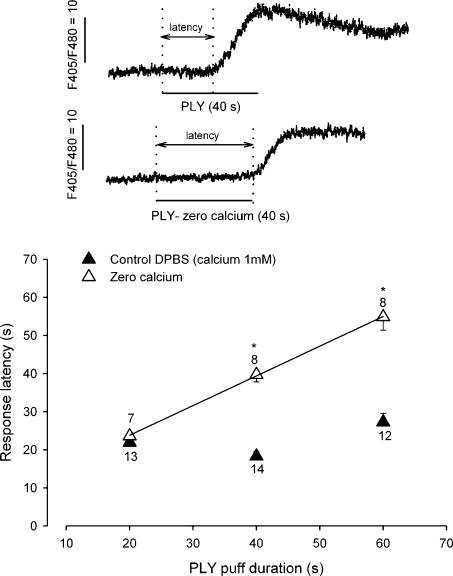

To define the source of calcium, we first tested the contribution of intracellular calcium stores to PLY toxicity. Thapsigargin, an inhibitor of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase, was added to the OC cultures for 24 h in the presence of PLY (1 ng μl−1). Cell toxicity was not decreased by thapsigargin (Fig. 5B). The participation of calcium influx, via voltage-dependent calcium channels, was also ruled out by determining the effect of the divalent cation blocker cobalt. When cobalt (50 μm) was simultaneously added to the culture medium with PLY (1 ng μl−1) and left for 24 h, the blockade of calcium channels did not prevent PLY toxicity (Fig. 5C). To determine the source of intracellular calcium, we monitored intracellular calcium in freshly dissociated rat HCs with spectrofluorimetry of indo-1 AM. The application of PLY (10 ng μl−1; 20 s) induced an increase in intracellular calcium in all IHCs (n = 6) and OHCs (n = 7) tested (Fig. 6). These calcium responses always began several seconds after the puff application and exhibited a response latency of 22 ± 2.2 s in both IHCs and OHCs. A lower concentration of PLY (1 ng μl−1, 20 s application) also induced an increase in intracellular calcium in HCs (n = 9) showing a similar response latency (25 ± 2 s). The calcium dependence of these events was determined by observing the effect of PLY in the absence of extracellular calcium. The PLY was prepared in a calcium-free medium (with 0.5 mm EGTA), and was applied for a short time (20 s) to isolated HCs via a pressure-puff. In control conditions (DPBS, 1 mm CaCl2), the latency of calcium responses remained constant relative to the PLY exposure time (Fig. 6). In the absence of external calcium (during the puff application), calcium-free PLY failed to evoke any calcium responses. However, a calcium increase occurred as soon as the puff exposure was ended, when cells were again surrounded by calcium (bath medium). The PLY exposure (zero calcium) was linearly related to the latency of the calcium response. The non-linearity observed with a 60 s puff application (latency 4 s shorter) was probably due to the diffusion of surrounding calcium consecutively to an irregular solution flow. A fit with a linear regression gave a correlation coefficient of 0.78 in zero calcium conditions. These results indicated the participation of external calcium in triggering the PLY-induced intracellular calcium increases.

Figure 6. PLY triggers a calcium increase in freshly isolated HC.

Intracellular calcium was monitored in rat isolated HCs using indo-1 spectrofluorimetry. The PLY (10 ng μl−1) was pressure-puffed on HCs. Traces show examples of an increase in calcium induced by PLY (40 s puff) in the presence of 1 mm CaCl2 (▴, control DPBS) or prepared in zero-calcium (▵). The arrows represent the response latency, the time elapsed between the start of PLY application and the intracellular calcium elevation. The graph represents the response latency as a function of the PLY exposure (puff duration) in control conditions (▴) and in the absence of external calcium (▵). The continuous line corresponds to a linear regression having a coefficient of 0.78 in zero calcium. The means (±s.e.m.) are from the number of HCs indicated on the plot. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between calcium conditions (unpaired t test, P < 0.001).

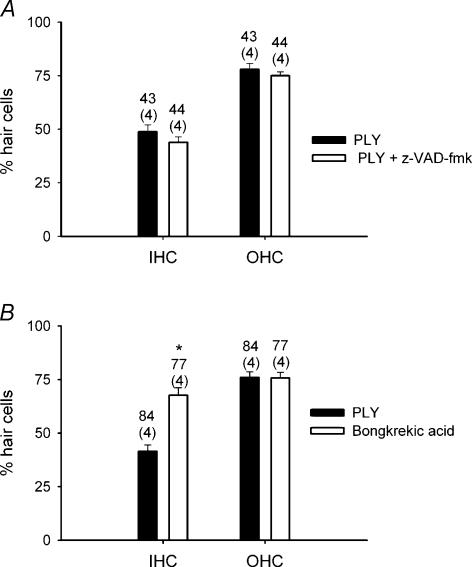

Our data (BAPTA) showed that PLY induced HC death via calcium-dependent mechanisms. To characterize the apoptotic molecular pathways mediated by PLY, we tested the possible participation of caspases in PLY toxicity. This was accomplished using a general caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk. Rat OCs were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of z-VAD-fmk. The presence or absence of a caspase inhibitor produced only random differences in PLY ototoxicity (Fig. 7A). These results ruled out the participation of caspases in HC death. Similarly, we investigated the possible involvement of mitochondrial apoptotic factors. This was tested using bongkrekic acid. Bongkrekic acid is known to inhibit the adenine nucleotide translocase, a protein component of the permeability transition pore complex (Gross et al. 1999). The ability of PLY to bind to the membrane was not modified by z-VAD-fmk (100 μm) or bongkrekic acid (20 μm), as the binding of eGFP-PLY to (freshly isolated) HC plasma membrane was unchanged by these agents (experiments not shown). Cultured OCs in the presence of bongkrekic acid (20 μm) significantly reduced PLY toxicity in IHCs (unpaired t test, P < 0.001), while no change was observed in OHCs (Fig. 7B). The protection afforded by bongkrekic acid was estimated to be ∼45% in IHCs. A protective effect (47%) by bongkrekic acid could only be observed in OHCs when using a higher PLY concentration (5 ng μl−1) (inducing ∼50% of damage for OHCs) (not shown). These data suggested the participation of mitochondrial apoptotic factors in HC death, with a preferential participation of these factors in IHC death when using a lower PLY concentration (1 ng μl−1).

Figure 7. Apoptotic pathways implicated in PLY-induced HC death.

Histograms show PLY toxicity in the presence of apoptotic blockers: A, a general caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk and B, a mitochondrial inhibitor, bongkrekic acid. Cultures were pretreated with z-VAD-fmk (100 μm) or bongkrekic acid (20 μm) prior to incubation with PLY (1 ng μl−1). Results are from the counts summed across the number of explants mentioned in parenthesis. Upper numbers indicated the number of fields counted to determine the average. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (unpaired t test, P < 0.001). Error bars show s.e.

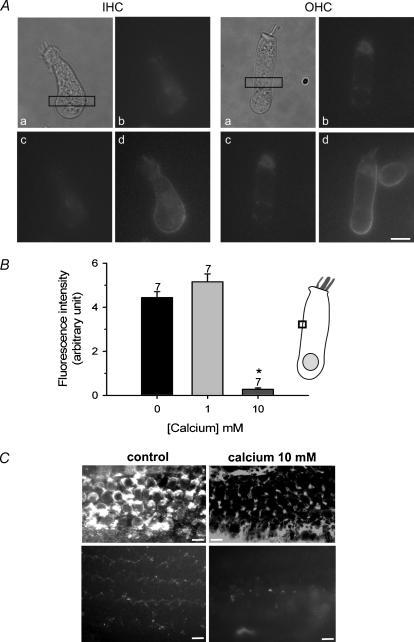

Elevation of external calcium prevents the toxicity of pneumolysin

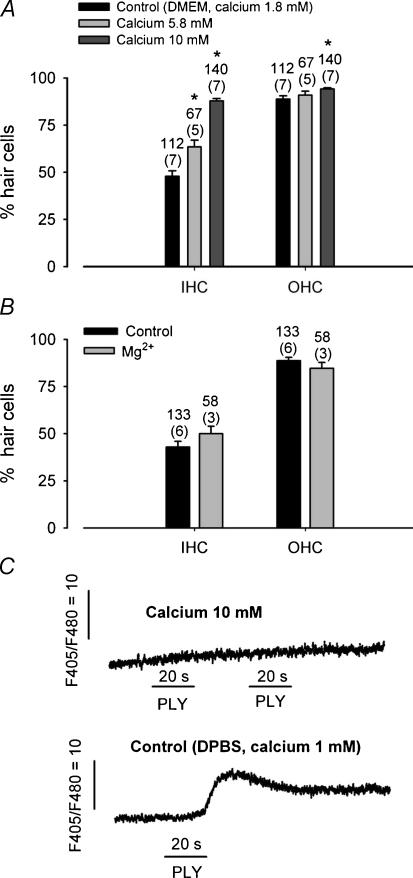

In planar lipid bilayers, PLY has been shown to induce channel formation (Korchev et al. 1992). These channels can be categorized on the basis of their ion selectivity, and by their sensitivity to closure by divalent cations (calcium). The present study suggested that PLY-induced HC death might be the result of the emergence of a calcium-permeable channel. However, the biophysical properties of these PLY-induced channels have not been described in living cells. To characterize these PLY-induced channels, we tested whether in vitro HC toxicity could be modulated by divalent cations. In liposomes, PLY-induced channels tended to remain open unless divalent cations were present (Korchev et al. 1992). We investigated the regulation of PLY-induced HC toxicity by divalent cations such as calcium. The HC PLY toxicity in organotypic cultures was tested in the presence of high external calcium concentrations (5.8 and 10 mm). OC cultures were treated for 24 h with PLY 1 ng μl−1. Figure 8A shows a significant reduction in the PLY-induced toxicity on HCs in the presence of high calcium in the culture medium. With PLY alone (control conditions, DMEM, 1.8 mm CaCl2), only 43.5 ± 2.8% of IHCs were present versus 87.8 ± 1.3% when 10 mm calcium was present. The protection by 10 mm calcium in the culture medium was estimated at 78% in IHCs and 49% in OHCs. The PLY toxicity was reduced by external calcium in a dose-related manner, and was minimal for high calcium concentration. Another cation (magnesium) has been tested and did not decrease PLY toxicity on HCs (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Rising extracellular calcium decreases PLY toxicity.

A, histogram shows the PLY toxicity as a function of the external calcium concentration. Toxicity of PLY on HCs is significantly decreased in the presence of a high external calcium concentration (5.8 and 10 mm) (unpaired t test, P < 0.001). Cultures were treated with PLY (1 ng μl−1) for 24 h. B, PLY toxicity in the presence of Mg2+. PLY (1 ng μl−1) was added to the OC cultures for 24 h in presence of control or 10 mm MgCl2. Cultures were treated with PLY (1 ng μl−1) for 24 h. Toxicity of PLY was unchanged in the presence of Mg2+. The number of explants used is indicated in parenthesis and the number of fields is indicated on the graph. C, intracellular calcium increase monitored by indo-1 in a freshly isolated IHC. PLY (10 ng μl−1) was pressure puffed for 20 s (horizontal lines) in the presence of 10 mm CaCl2 (top trace) and in control conditions (1 mm CaCl2) in the same IHC. The upper and lower traces are separated by 1 min. The presence of high external calcium concentration inhibits the PLY-induced calcium increase. Error bars show s.e.

We also examined, in freshly isolated rat HCs, whether PLY induced an increase in intracellular calcium in presence of high calcium concentration. In that situation, intracellular calcium increases were no longer triggered by a local application of PLY (Fig. 8C). However, a puff of PLY (10 ng μl−1) on the same IHC in the presence of control calcium conditions (DPBS, 1 mm CaCl2) evoked an increase of intracellular calcium. Altogether, these data reveal a role for external calcium in the regulation of PLY activity.

The inhibition of PLY by external calcium could result from closure of the PLY-induced channels, as has been described in lipid bilayers (Korchev et al. 1998), or by its decreased incorporation into the plasma membrane. To test this second hypothesis, we monitored the binding of eGFP-PLY, as a function of external calcium concentration, in isolated HCs. In the presence of 10 mm extracellular calcium (prepared in DPBS or in a phosphate-free medium), eGFP-PLY (5 ng μl−1) did not bind to IHCs or OHCs (Fig. 9A). On the same HCs, when high calcium was replaced by control conditions (DPBS, 1 mm CaCl2), eGFP-PLY was incorporated into the plasma membrane and stereocilia of IHCs and OHCs. In addition, when eGFP-PLY was first applied to HCs in control conditions, a subsequent application of 10 mm calcium did not modify the fluorescent signal of the cell membrane (data not shown). This result suggests that the fluorescence of eGFP was not affected by high calcium conditions. A quantification of the eGFP-PLY fluorescence located in the HC membrane showed a similar signal intensity in the presence (control DPBS) or absence of calcium (zero-calcium) (Fig. 9B). However, elevation of external calcium (10 mm) drastically reduced the association of fluorescent PLY with the plasma membrane. These results suggested that the reduction of HC toxicity by 10 mm calcium was due to the prevention of protein binding to the HC plasma membrane rather than the modification of the PLY-induced channel conductance shown by others (Korchev et al. 1992, 1998). In additional experiments, we examined the binding distribution of PLY in cultured OC in the presence of control (DMEM: 1.8 mm) or high (10 mm) calcium using a PLY-specific antibody (Fig. 9C) or the labelled toxin eGFP-PLY. In both cases the staining was drastically reduced in high calcium. The labelling of the plasma membrane and hair bundles could not be observed in the HC region.

Figure 9. Elevation of extracellular calcium prevents binding of eGFP-PLY to HCs.

A, the eGFP-PLY (5 ng μl−1) was pressure puffed for 5 s on isolated rat IHC and OHC shown in (a). Fluorescent images before (b) and after the puff of PLY in 10 mm (c) or 1 mm (control) CaCl2 (d) in the same IHC and OHC. In the presence of 10 mm CaCl2, eGFP-PLY is not seen in the HC membrane while a strong signal is present in control conditions. B, histogram represents the intensity of eGFP-PLY fluorescence bound to the HC plasma membrane as a function of external calcium concentration. eGFP-PLY (5 ng μl−1) was pressure puffed for 5 s on isolated rat HC. Fluorescence intensity was measured in a fixed-size area of the plasma membrane, illustrated by the box in the HC scheme. Fluorescence intensity corresponds to F−F0. The asterisk indicates a significant different data (unpaired t test, P < 0.001). Results are obtained over the number of indicated cells. C, top images show the immunolocalization of PLY in PLY (1 ng μl−1, 24 h) -treated OC cultures (n = 4) in the presence of control (left panel) (DMEM 1.8 mm CaCl2) or high external calcium concentration (right panel) (10 mm). Bottom images show binding of eGFP-PLY in OC cultures treated 24 h with 1 ng μl−1 in the presence of control or high external calcium concentration (representative of four explants for each condition). Surface preparation of the OC showed a staining of stereocilia and plasma membrane of IHCs and OHCs in control condition, while no labelling was observed in high calcium. Error bars show s.e. Scale bars 10 μm.

Pneumolysin is also known to damage central neurones via calcium-dependent apoptotic pathways (Braun et al. 2001, 2002; Stringaris et al. 2002). We have explored whether extracellular calcium could also interfere with the membrane binding of PLY in rat hippocampal neurones. We monitored the binding of eGFP-PLY as a function of external calcium (Fig. 10). In control conditions (DPBS, 1 mm CaCl2) or in 10 mm calcium, eGFP-PLY (10 ng μl−1) did bind to the cell membranes of neurones. The distribution of eGFP-PLY was restricted to the cell surface and no significant difference in fluorescence intensity could be observed in the presence of control or high external calcium.

Figure 10. Binding of eGFP-PLY on hippocampal neurones is not reduced in the presence of high extracellular calcium.

The eGFP-PLY (10 ng μl−1) was pressure puffed for 10 s on rat hippocampal neurones. Fluorescent images of two neurones are shown after the puff of PLY prepared in control conditions (DPBS, 1 mm CaCl2) (a) or in 10 mm (b) CaCl2. The histogram represents the intensity of eGFP-PLY fluorescence bound to the HC plasma membrane as a function of external calcium concentration. Fluorescence intensity was measured in a fixed-size area of the plasma membrane. Fluorescence intensity corresponds to F−F0. Results were obtained over the number of indicated cells. Error bars show s.e. Scale bars 10 μm.

Discussion

The goal of our experiments was to characterize the mechanisms of action of PLY on cochlear HCs. The in vitro PLY treatment of OC cultures resulted in the preferential destruction of IHCs. Morphological features of these HCs implicated an apoptotic rather than a necrotic cell death mechanism. In addition, we found that PLY-induced cell death was triggered by an extracellular influx of calcium, and blocked by an increase in extracellular calcium concentration.

PLY cytotoxicity in the sensory HCs was dose dependent. At low PLY concentrations, only IHCs were affected, while high concentrations induced cell death in both IHCs and OHCs. A preferential toxicity towards IHCs has already been described in an in vivo study (Skinner et al. 2004). Moreover, at high concentration, PLY induced severe damage with a total destruction of HCs. In contrast to a previous in vivo study (Comis et al. 1993), we did not see any differential cell death between the three OHC rows or between HCs located in the apex or the base of the OC. In that previous study, intracochlear perfusion of PLY in guinea pigs induced severe morphological damage to both IHCs and OHCs. The severity of the damage increased from row one to row three of the OHCs, and was more pronounced in HCs located in the apex of the OC than in the base. These differences to our present study could be due to species (guinea pig versus rat), age (adult versus young), doses used, or to a different access to the OC (in vivoversusin vitro). The range of PLY concentrations used here, and the concentration levels required to damage HCs, were consistent with those used in organotypic hippocampal cultures or neuronal cell line (Stringaris et al. 2002) or vascular cells (Zysk et al. 2001).

Pneumococcal meningitis is a common cause of profound deafness. Hearing loss results from the spread of the infection from the cerebrospinal fluid to the labyrinth via the cochlear aqueduct (Bhatt et al. 1991, 1993). Deafness associated with meningitis is almost certainly a result of cochlear damage. A model of meningogenic deafness showed that PLY induced specific and devastating cochlear damage (Winter et al. 1997). Intracranial inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae, unable to produce PLY, failed to induce cochlear damage and hearing loss, while meningeal inflammation was still present. The severe morphological damage to HCs (stereocilia disorganization, cell loss) induced by PLY in our experiments strongly resembles the changes attributed to pneumococcal meningitis (Winter et al. 1997) or intracochlear perfusion of purified PLY (Comis et al. 1993).

Apoptotic and necrotic HC death was discerned with a TUNEL assay and a propidium iodide staining. With low and middle-range concentrations of PLY (1–5 ng μl−1), necrotic HC death was absent, while apoptotic cell death was observed. In addition, examination of semithin sections failed to reveal any necrotic cell features. However, apoptotic features, such as cell shrinkage, the abnormal presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles and inclusions, and to a lesser extent chromatin condensation, were observed. These results lead to the conclusion that PLY causes apoptotic HC death. This is in agreement with other studies on central neurones (Braun et al. 2002; Stringaris et al. 2002). Surprisingly, we observed that DNA fragmentation, revealed by TUNEL technique, was low (15%) in comparison to the total number of missing HCs (61%). The examination of semithin sections (only a few nuclei with chromatin condensation were present in our OC cultures) supports this observation. However, the apoptotic characteristic of chromatin condensation could be commonly observed in the PLY-treated spiral ganglion neurones. The percentage of missing HCs, which was not revealed by a TUNEL labelling, may reflect an atypical apoptotic cell death, without DNA fragmentation.

We showed that calcium played an important role in PLY-induced HC death since the HC destruction was significantly decreased by buffering intracellular calcium with BAPTA. The participation of calcium in cell death has been largely described and is generally reported to be crucial in apoptotic mechanisms (Orrenius et al. 2003). An elevation of cytosolic calcium can lead to the release of mitochondrial apoptotic factors such as cytochrome c or apoptosis-induced factor (AIF) (Susin et al. 1999). In our study, the addition of bongkrekic acid, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, significantly decreased the toxicity of PLY on HCs, and supported the participation of a mitochondria-mediated pathway in HC death. Interestingly, the protective effect of bongkrekic acid was more pronounced in IHCs than in OHCs when using a lower PLY concentration (1 ng μl−1), and could explain the differential effect of PLY on IHCs and OHCs. Unlike BAPTA, bongkrekic acid did not decrease PLY toxicity (at 1 ng μl−1) in OHCs. These data could suggest the participation of other calcium-dependent apoptotic pathways in OHC death. However, the absence of protection by z-VAD-fmk excludes the implication of caspases in PLY-induced sensory HC death.

PLY induced an intracellular calcium increase in HCs. This calcium increase did not come from intracellular stores or from an influx via voltage-gated calcium channels, because the use of thapsigargin and cobalt failed to prevent HC death. In addition, PLY could not evoke a calcium increase in the absence of external calcium, suggesting that extracellular calcium was required to induce PLY toxicity. PLY is a member of a large family of pore-forming bacterial toxins (Alouf, 2000), and this calcium is probably entering the cell through a pore created by PLY. Pore formation requires the binding of toxin monomers to cholesterol. The PLY monomers are inserted into the lipid bilayer to create pores whose size can reach 35–45 nm in diameter (Gilbert et al. 1999; Bonev et al. 2001). The pore-forming activity of PLY is required to induce cell apoptosis, since a cytolytic-deficient PLY construct (Andrew et al. 1997) was unable to induce cell death (Braun et al. 2002).

In freshly dissociated HCs, a puff of PLY induced an increase in intracellular calcium with a latency of ∼22 s. This latency (control conditions) is constant and does not depend on the duration of PLY exposure. This latency may reflect the time necessary for the formation of the PLY pores in the cell membrane.

IHCs were preferentially destroyed by the toxin over OHCs, in both a dose- and time-dependent manner. This observation is remarkable since most of the known effects on exposure to ototoxic drugs or intense sounds results first in damage to OHCs and then injuries to IHCs. Only carboplatin, an antineoplastic drug, was shown to selectively damage IHCs in chinchillas (Takeno et al. 1994). The differential effect of PLY on IHCs and OHCs observed here cannot be explained by a difference in cell binding of the toxin. Both immunolabelling using PLY antibody and a puff of fluorescent-conjugated PLY, showed a similar pattern of toxin distribution between IHCs and OHCs. PLY binds to membrane cholesterol, and a difference in lipid composition can affect this binding, and thus the resulting pore formation (Nollmann et al. 2004). The possibility of differential PLY binding to membranes has been proposed to explain differences in PLY sensitivity in other cell types (Hirst et al. 2002).

The differential effect of PLY on IHCs and OHCs could also be explained by different calcium-buffering systems in these cells. The OHCs are characterized by the presence of a subsurface cisternae lying beneath the lateral plasma membrane (Holley & Ashmore, 1988). This network of cisternae is thought to serve as a calcium-sequestering store that would limit calcium entry into OHCs, through the pore formed by PLY, thus limiting an apoptotic response. In addition, a different distribution of calcium-binding proteins has been observed between IHCs and OHCs (Slepecky & Ulfendahl, 1993; Pack & Slepecky, 1995; Sakaguchi et al. 1998). This difference in calcium-buffering capacity between HC types could also account for their differential susceptibility to PLY.

In living cells, PLY is shown to form calcium-permeable pores (Cockeran et al. 2001; Stringaris et al. 2002), but the biophysical properties of these channels are poorly characterized. However, in planar lipid bilayers, PLY induces channel formation with a wide range of conductances (Korchev et al. 1992). The PLY channels are classified on the basis of their cation/anion selectivity and by their sensitivity to closure by divalent cations (Korchev et al. 1992). Remarkably, we showed that PLY-induced HC death in vitro was largely decreased by increasing the extracellular calcium concentration. This effect was dose dependent and calcium specific, since another divalent cation (magnesium) was ineffective in preventing HC death. Moreover, only calcium (at high concentration) inhibited the binding of PLY to HC membranes, as indicated by the absence of eGFP-PLY labelling. The present findings suggest that extracellular calcium blocks the binding of PLY in the cell membrane of HCs, perhaps by affecting the conformation of the binding sites of the toxin to the cell membrane. Interestingly, this block of PLY binding in the presence of high external calcium was not observed in neuronal cells, suggesting a binding mechanism specific to HCs. This might result from a different lipid/cholesterol composition between HCs and the neuronal plasma membrane. A difference in lipid composition has indeed been shown to affect the PLY binding to membrane cholesterol and thus the resulting pore formation (Nollmann et al. 2004).

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that PLY-induced HC death affects IHCs preferentially. This may be due to the different cellular and membrane characteristics of IHCs and OHCs. In addition, calcium appears to play a dual role. On one hand, at moderate concentrations, it triggers cell death via the PLY channel and activation of apoptosis, while on the other, it prevents cell death, at high concentrations, by inhibiting the ability of PLY to bind to the membrane. Pneumolysin remains a major virulence factor associated with severe diseases like meningitis, pneumonia or otitis media. Its role in pathogenicity is intimately dependent on an ability to form transmembrane pores by binding with cholesterol in target tissues. It is possible that blockage of PLY binding to cell membranes in the presence of high calcium concentration may provide new insights for therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr James C. Saunders, Dr Jean-Marie Aran, Dr Jean-Michel Sallenave and Dr Vincent Darrouzet for their invaluable help and comments during the preparation of this manuscript. We are grateful to Delphine Bouchet for providing brain cell cultures. Pr. Jean-Pierre Bébéar, Head of the Department of Otolaryngology, Hôpital Pellegrin, deserves a special mention for his continuing support for our research laboratory. This research was supported by grants from the National University of Ireland and CRS Amplifon. Graeme Cowan was supported by a scholarship from the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow.

References

- Alonso de Velasco E, Verheul AF, Verhoef E, Snippe H. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors, pathogene and vaccines. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:591–603. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.591-603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alouf J. Cholesterol-binding cytolytic protein toxins. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:351–356. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew PW, Mitchell TJ, Morgan PJ. Relationship of structure to function in pneumolysin. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:11–17. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Halpin C, Hsu W, Thedinger BA, Levine RA, Tuomanen E, Nadol JB. Hearing loss and pneumococcal meningitis: an animal model. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1285–1292. doi: 10.1002/lary.5541011206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt SM, Lauretano A, Cabellos C, Halpin C, Levine RA, Xu WZ, Nadol JB, Tuomanen E. Progression of hearing loss in experimental pneumococcal meningitis: correlation with cerebrospinal fluid cytochemistry. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:675–683. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer D, Brors D, Pak K, Bodmer M, Ryan AF. Gentamicin-induced hair cell death is not dependent on the apoptosis receptor Fas. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:452–455. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonev BB, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Byron O, Watts A. Structural analysis of the protein/lipid complexes associated with pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5714–5719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JS, Novak R, Murray PJ, Eischen CM, Susin SA, Kroemer G, Halle A, Weber JR, Tuomanen EI, Cleveland JL. Apoptosis-inducing factor mediates microglial and neuronal apoptosis caused by pneumococcus. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1300–1309. doi: 10.1086/324013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JS, Sublett JE, Freyer D, Mitchell TJ, Cleveland JL, Tuomanen EI, Weber JR. Pneumococcal pneumolysin and H2O2 mediate brain cell apoptosis during meningitis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:19–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, Rubel EW. Hair cell death in the avian basilar papilla: characterization of the in vitro model and caspase activation. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4:91–105. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockeran R, Theron AJ, Steel HC, Matlola NM, Mitchell TJ, Feldman C, Anderson R. Proinflammatory interactions of pneumolysin with human neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:604–611. doi: 10.1086/318536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comis SD, Osborne MP, Stephen J, Tarlow MJ, Hayward TL, Mitchell TJ, Andrew PW, Boulnois GJ. Cytotoxic effects on hair cells of guinea pig cochlea produced by pneumolysin, the thiol activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113:152–159. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge PR, Davis H, Feigin RD, Holmes SJ, Kaplan SL, Jubelirer DP, Stechenberg BW, Hirsh SK. Prospective evaluation of hearing impairment as a sequela of acute bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:869–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Mollard P, Aran JM. Extracellular ATP elevates cytosolic Ca2+ in cochlear inner hair cells. Neuroreport. 1991;2:69–72. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont A, Hehner SP, Hofmann TG, Ueffing M, Droge W, Schmitz ML. Hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis is CD95-independent, requires the release of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species and the activation of NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 1999;18:747–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, Miller SI, Southwick FS, Caviness VS, Swartz MN. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:21–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301073280104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Li L. Apoptotic death of hair cells in mammalian vestibular sensory epithelia. Hear Res. 2000;139:97–115. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag NE, Jacobs KE. Examination of Listeria monocytogenes intracellular gene expression by using the green fluorescent protein of Aequorea victoria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1844–1852. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1844-1852.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong IJ, Lopez Mediavilla C, Ascaso R, Lopez Rivas A, Collins MK. Induction of apoptosis by valinomycin: mitochondrial permeability transition causes intracellular acidification. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:214–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert RJ, Jimenez JL, Chen S, Tickle IJ, Rossjohn J, Parker M, Andrew PW, Saibil HR. Two structural transitions in membrane pore formation by pneumolysin, the pore-forming toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Cell. 1999;97:647–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslin K, Banker G. Rat hippocampal neurons in low density culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1991. pp. 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;15:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst RA, Yesilkaya H, Clitheroe E, Rutman A, Dufty N, Mitchell TJ, O'Callaghan C, Andrew PW. Sensitivities of human monocytes and epithelial cells to pneumolysin are different. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1017–1022. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.1017-1022.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley MC, Ashmore JF. A cytoskeletal spring in cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 1988;335:635–637. doi: 10.1038/335635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesser BW, Hashisaki GT, Spindel JH, Ruth RA, Scheld WM. Time course of hearing loss in an animal model of pneumococcal meningitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:628–637. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a92772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopke RD, Liu W, Gabaizadeh R, Jacono A, Feghali J, Spray D, Garcia P, Steinman H, Malgrange B, Ruben RJ, Rybak L, Van de Water TR. Use of organotypic cultures of Corti's organ to study the protective effects of antioxidant molecules on cisplatin-induced damage of auditory hair cells. Am J Otol. 1997;18:559–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korchev YE, Bashford CL, Pasternak CA. Differential sensitivity of pneumolysin-induced channels to gating by divalent cations. J Membr Biol. 1992;127:195–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00231507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korchev YE, Bashford CL, Pederzolli C, Pasternak CA, Morgan PJ, Andrew PW, Mitchell TJ. A conserved tryptophan in pneumolysin is a determinant of the characteristics of channels formed by pneumolysin in cells and planar lipid bilayers. Biochem J. 1998;329:571–577. doi: 10.1042/bj3290571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui JI, Gale JE, Warchol ME. Critical signaling events during the aminoglycoside-induced death of sensory hair cells in vitro. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:250–266. doi: 10.1002/neu.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TJ. Virulence factors and the pathogenesis of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Res Microbiol. 2000;151:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)00175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TJ, Andrew PW. Biological properties of pneumolysin. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:19–26. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TJ, Walker JA, Saunders FK, Andrew PW, Boulnois GJ. Expression of the pneumolysin gene in Escherichia coli: Rapid purification and biological properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;1007:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollmann M, Gilbert R, Mitchell T, Sferrazza M, Byron O. The role of cholesterol in the activity of pneumolysin, a bacterial protein toxin. Biophys J. 2004;86:3141–3151. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74362-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak R, Charpentier E, Braun JS, Park E, Murti S, Tuomanen E, Masure R. Extracellular targeting of choline-binding proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae by a zinc metalloprotease. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:366–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne MP, Comis SD, Tarlow MJ, Stephen J. The cochlear lesion in experimental bacterial meningitis of the rabbit. Int J Exp Pathol. 1995;76:317–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack AK, Slepecky NB. Cytoskeletal and calcium-binding proteins in the mammalian organ of Corti: cell type-specific proteins displaying longitudinal and radial gradients. Hear Res. 1995;91:119–135. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JC, Andrew PW, Boulnois GJ, Mitchell TJ. Molecular analysis of the pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae: the role of pneumococcal proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:89–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi N, Henzl MT, Thalmann I, Thalmann R, Schulte BA. Oncomodulin is expressed exclusively by outer hair cells in the organ of Corti. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:29–40. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders FK, Mitchell TJ, Walker JA, Andrew PW, Boulnois GJ. Pneumolysin, the thiol-activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, does not require a thiol group for in vitro activity. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2547–2552. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2547-2552.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner LJ, Beurg M, Mitchell TJ, Darrouzet V, Aran JM, Dulon D. Intracochlear perfusion of pneumolysin, a pneumococcal protein, rapidly abolishes auditory potentials in the guinea pig cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00016480410017125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepecky NB, Ulfendahl M. Evidence for calcium-binding proteins and calcium-dependent regulatory proteins in sensory cells of the organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1993;70:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris AK, Geisenhainer J, Bergmann F, Balshusemann C, Lee U, Zysk G, Mitchell TJ, Keller BU, Kuhnt U, Gerber J, Spreer A, Bahr M, Michel U, Nau R. Neurotoxicity of pneumolysin, a major pneumococcal virulence factor, involves calcium influx and depends on activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11:355–368. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeno S, Harrison RV, Mount RV, Wake M, Harada Y. Induction of selective inner hair cell damage by carboplatin. Scann Electr Microsc. 1994;8:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomanen EI, Austrian R, Masure HR. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1280–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505113321907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter AJ, Comis SD, Osborne MP, Tarlow MJ, Stephen J, Andrew PW, Hill J, Mitchell TJ. A role for pneumolysin but not neuraminidase in the hearing loss and cochlear damage induced by experimental pneumococcal meningitis in guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4411–4418. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4411-4418.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter AJ, Marwick S, Osborne M, Comis S, Stephen J, Tarlow M. Ultrastructural damage to the organ of corti during acute experimental Escherichia coli and pneumococcal meningitis in guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 1996;116:401–407. doi: 10.3109/00016489609137864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M. Necrotic cell death in C. elegans requires the function of calreticulin and regulators of Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum. Neuron. 2001;31:957–971. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zysk G, Schneider-Wald BK, Hwang JH, Bejo L, Kim KS, Mitchell TJ, Hakenbeck R, Heinz HP. Pneumolysin is the main inducer of cytotoxicity to brain microvascular endothelial cells caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2001;69:845–852. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.845-852.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]