Abstract

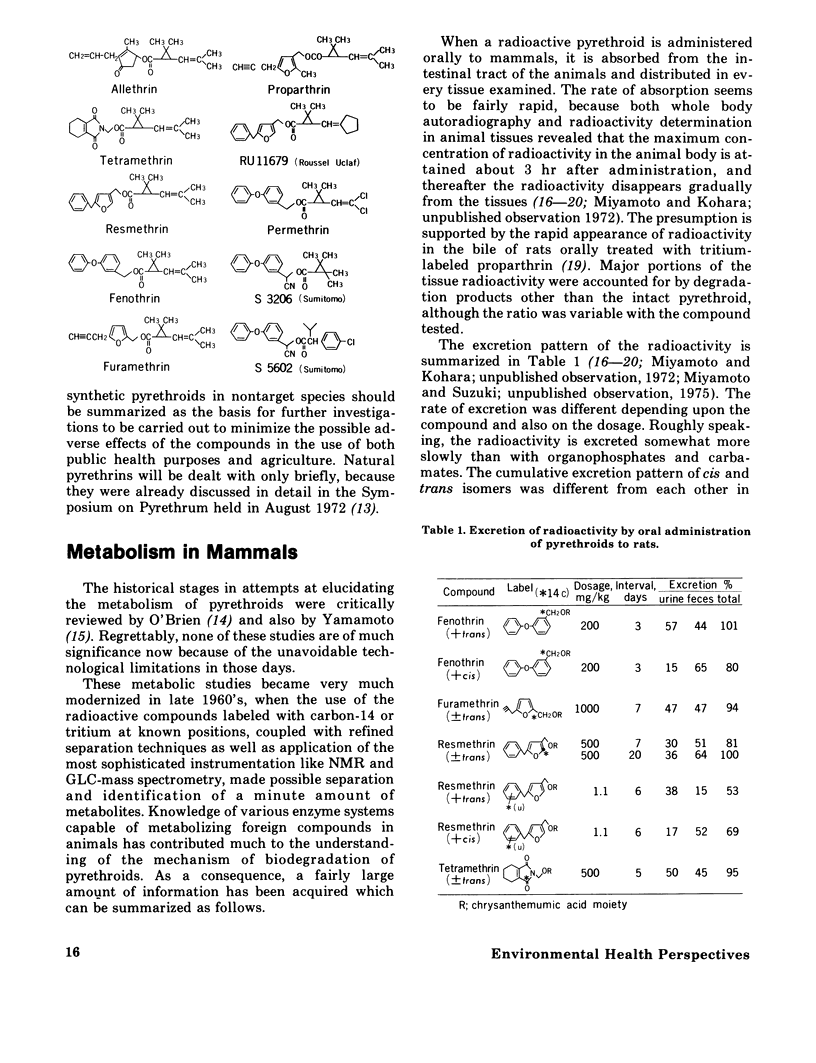

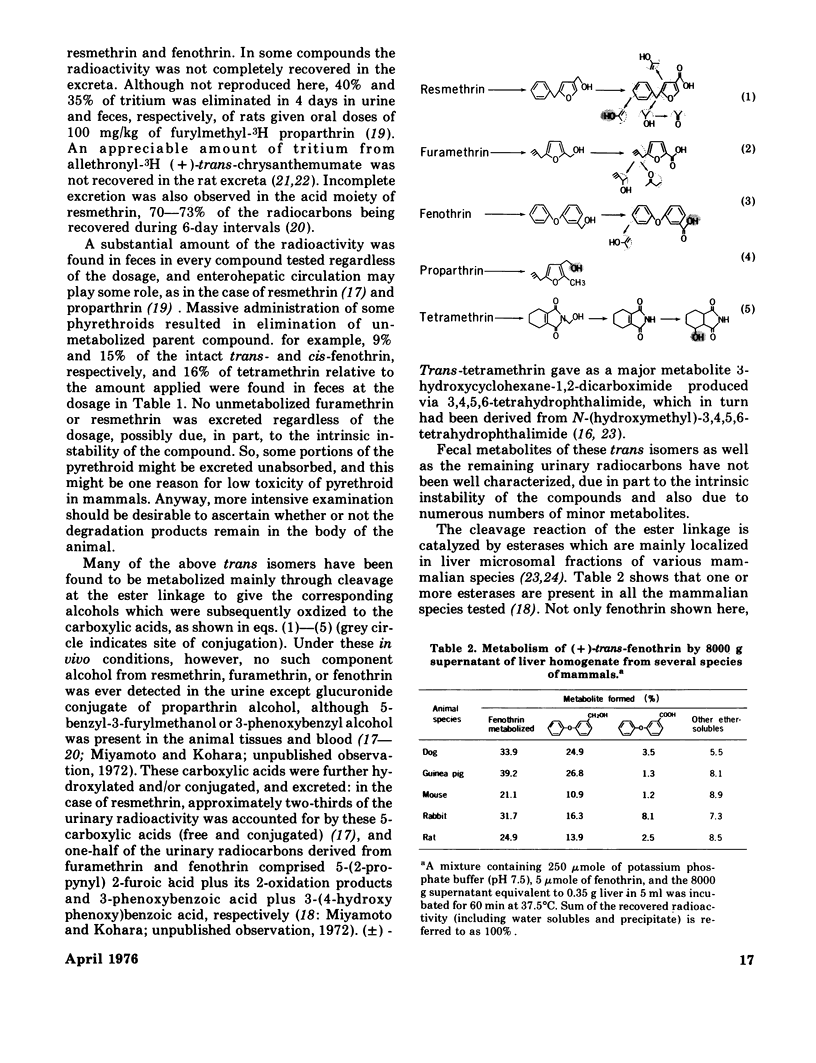

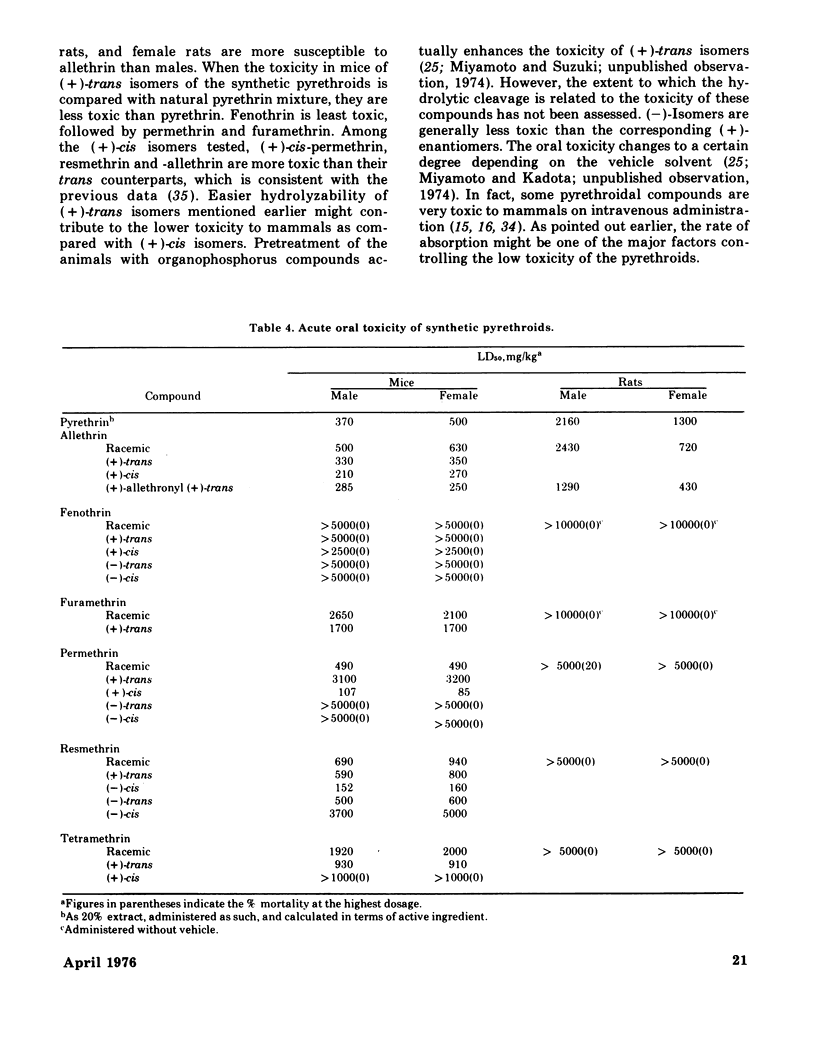

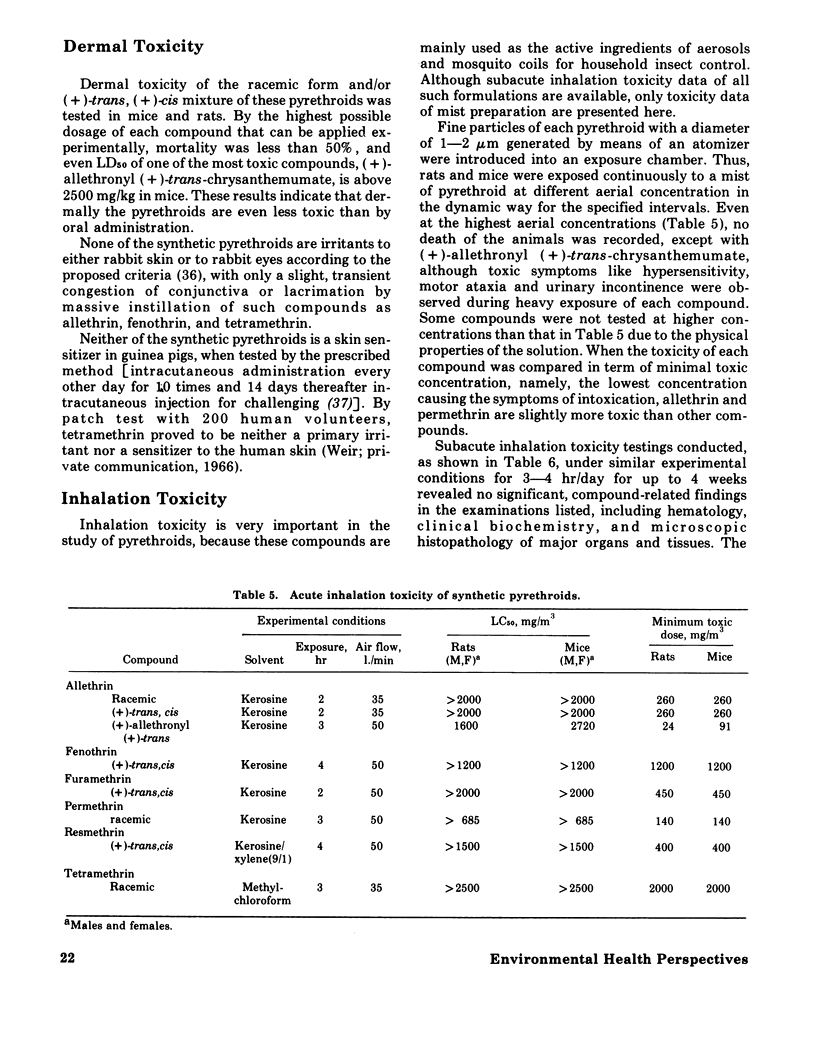

Synthetic pyrethroidal compounds undergo biodegradation in mammals both oxidatively and hydrolytically, and depending on the type of compound, either of the pathways may predominate. Thus, (+) - or (+/-) -trans isomers of the chrysanthemumate ester of primary alcohols such as fenothrin, furamethrin, proparthrin, resmethrin, and tetramethrin (and possibly permethrin, too) are metabolized mainly through hydrolysis of the ester linkage, with subsequent oxidation and/or conjugation of the component alcohol and acid moieties. On the other hand, the corresponding (+)-cis enantiometers and chrysanthemumate of secondary alcohols like allethrin are resistant to hydrolytic attack, and biodegraded via oxidation at various sites of the molecule. These rapid metabolic degradations, together with the presumable incomplete absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, would generally contribute to the low acute toxicity of synthetic pyrethroids. These compounds are neither skin irritants nor skin sensitizers, and inhalation toxicity as well as dermal toxicity are fairly low. Neither is teratogenic in rats, mice, and/or rabbits or mutagenic on various bacterial strains. Subacute and chronic feeding of higher amounts of the compounds to rats invariably causes some histopathological changes in liver; however, these are neither indicative nor suggestive of tumorigenicity. Based on existing toxicological information, the present recommended use patterns might afford sufficient safety margin on human population. However, in extending usage to agricultural pest control, much more extensive investigations should be forthcoming from both chemical and biological aspects, since there is scant information on the fate of these pyrethroids in the environment. Also several of the compounds may be very toxic to certain kinds of fish and arthropods.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abernathy C. O., Casida J. E. Pyrethroid insecticides: esterase cleavage in relation to selective toxicity. Science. 1973 Mar 23;179(4079):1235–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4079.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B. N., Lee F. D., Durston W. E. An improved bacterial test system for the detection and classification of mutagens and carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Mar;70(3):782–786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berteau P. E., Casida J. E., Narahashi T. Pyrethroid-like biological activity of compounds lacking cyclopropane and ester groupings. Science. 1968 Sep 13;161(3846):1151–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3846.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G., Bodenstein O. F., Norton S. J. New potent pyrethroid, bromethrin. J Agric Food Chem. 1973 Sep-Oct;21(5):767–769. doi: 10.1021/jf60189a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casida J. E., Kimmel E. C., Elliott M., Janes N. F. Oxidative metabolism of pyrethrins in mammals. Nature. 1971 Apr 2;230(5292):326–327. doi: 10.1038/230326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M., Farnham A. W., Janes N. F., Needham P. H., Pulman D. A. Potent pyrethroid insecticides from modified cyclopropane acids. Nature. 1973 Aug 17;244(5416):456–457. doi: 10.1038/244456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M., Farnham A. W., Janes N. F., Needham P. H., Pulman D. A., Stevenson J. H. A photostable pyrethroid. Nature. 1973 Nov 16;246(5429):169–170. doi: 10.1038/246169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M., Farnham A. W., Janes N. F., Needham P. H., Pulman D. A. Synthetic insecticide with a new order of activity. Nature. 1974 Apr 19;248(5450):710–711. doi: 10.1038/248710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M., Janes N. F., Kimmel E. C., Casida J. E. Metabolic fate of pyrethrin I, Pyrethrin II, and allethrin administered orally to rats. J Agric Food Chem. 1972 Mar-Apr;20(2):300–313. doi: 10.1021/jf60180a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kada T., Tutikawa K., Sadaie Y. In vitro and host-mediated "rec-assay" procedures for screening chemical mutagens; and phloxine, a mutagenic red dye detected. Mutat Res. 1972 Oct;16(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(72)90177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H., Shimada K., Tomizawa J. Studies on radiation-sensitive mutants of E. coli. I. Mutants defective in the repair synthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1968 May 3;101(3):227–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00271625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater E. E., Anderson M. D., Rosenkranz H. S. Rapid detection of mutagens and carcinogens. Cancer Res. 1971 Jul;31(7):970–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K., Gaughan L. C., Casida J. E. Metabolism of (+)-trans- and (+)-cis-resmethrin in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 1975 Jan-Feb;23(1):106–115. doi: 10.1021/jf60197a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K., Gaughan L. C., Casida J. E. Photodecomposition of resmethrin and related pyrethroids. J Agric Food Chem. 1974 Mar-Apr;22(2):212–220. doi: 10.1021/jf60192a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]