Abstract

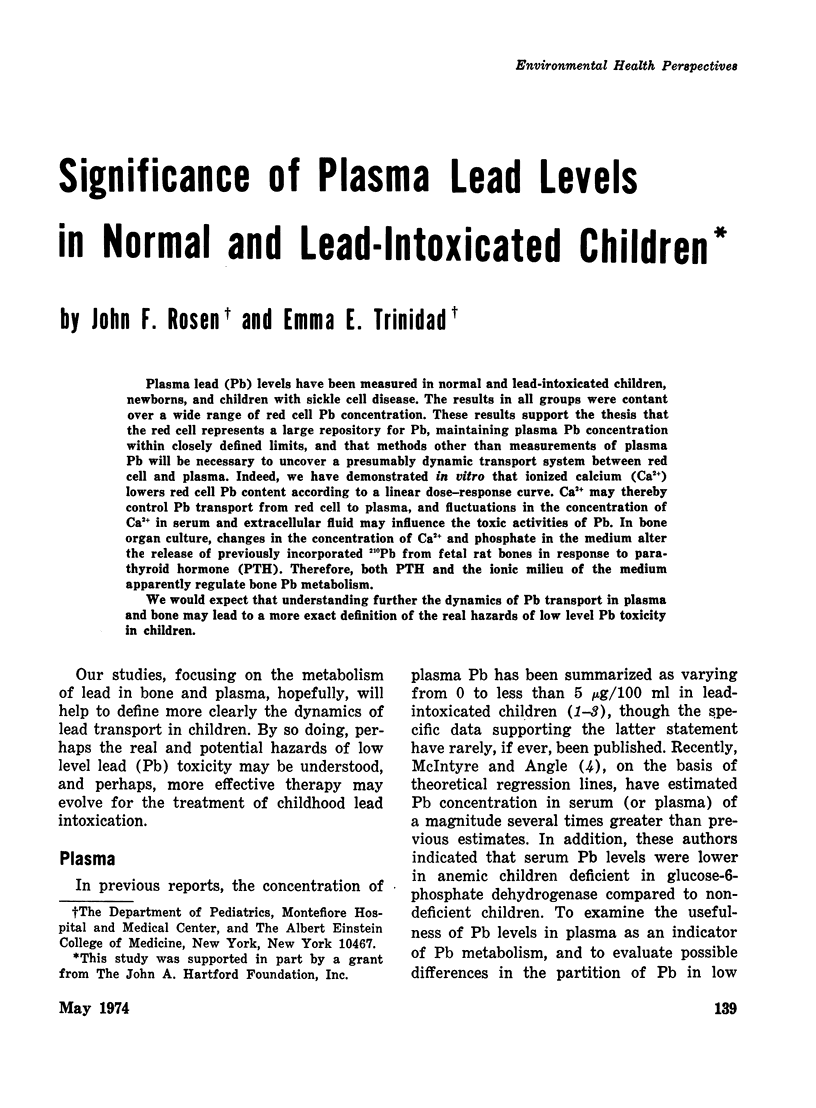

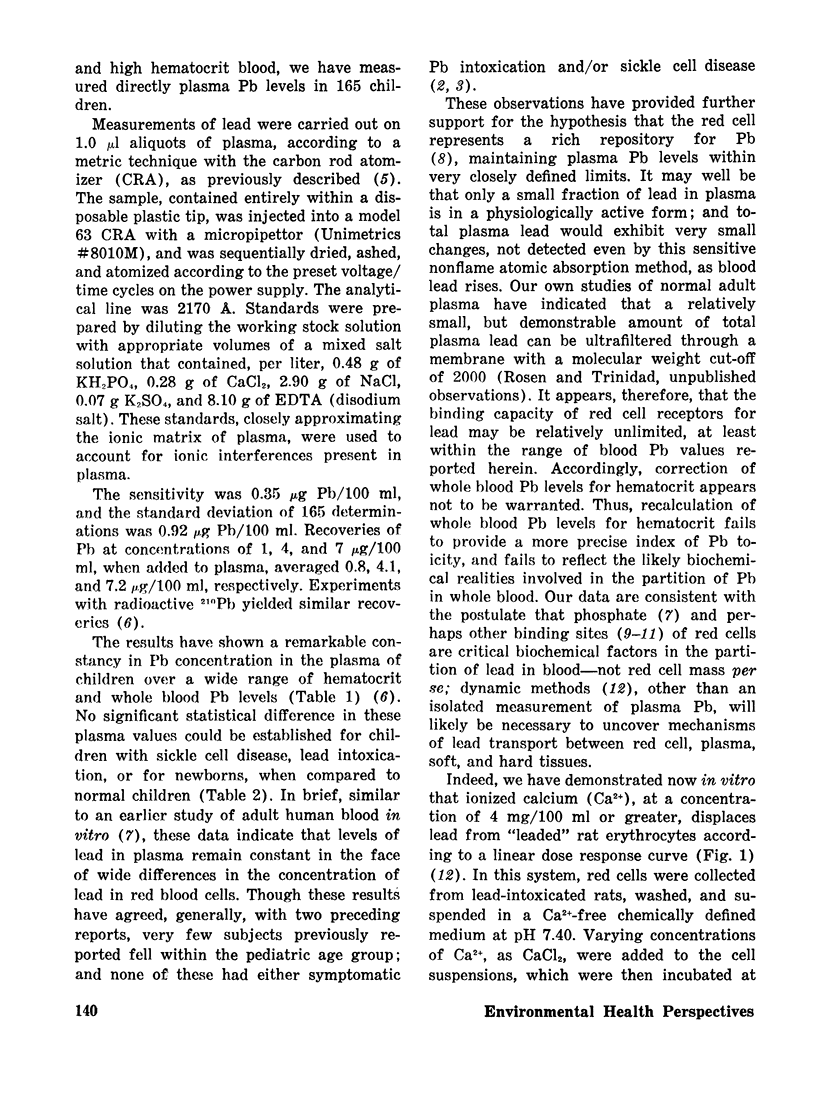

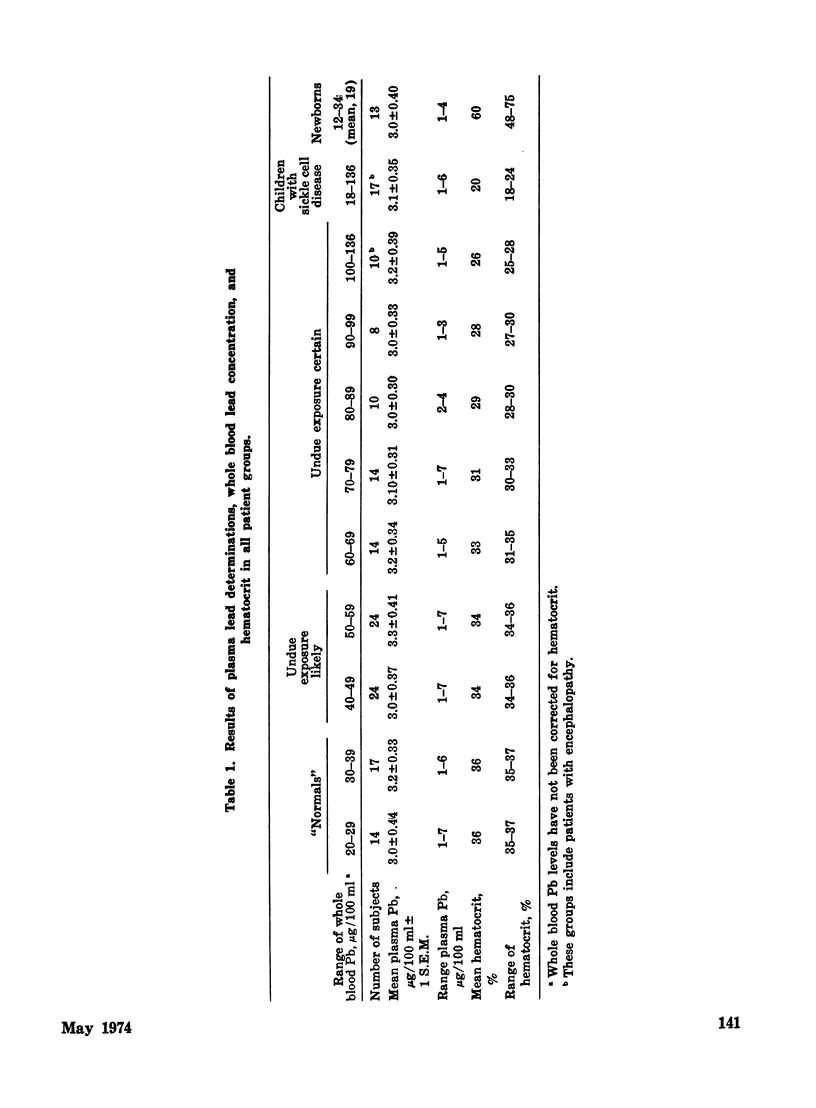

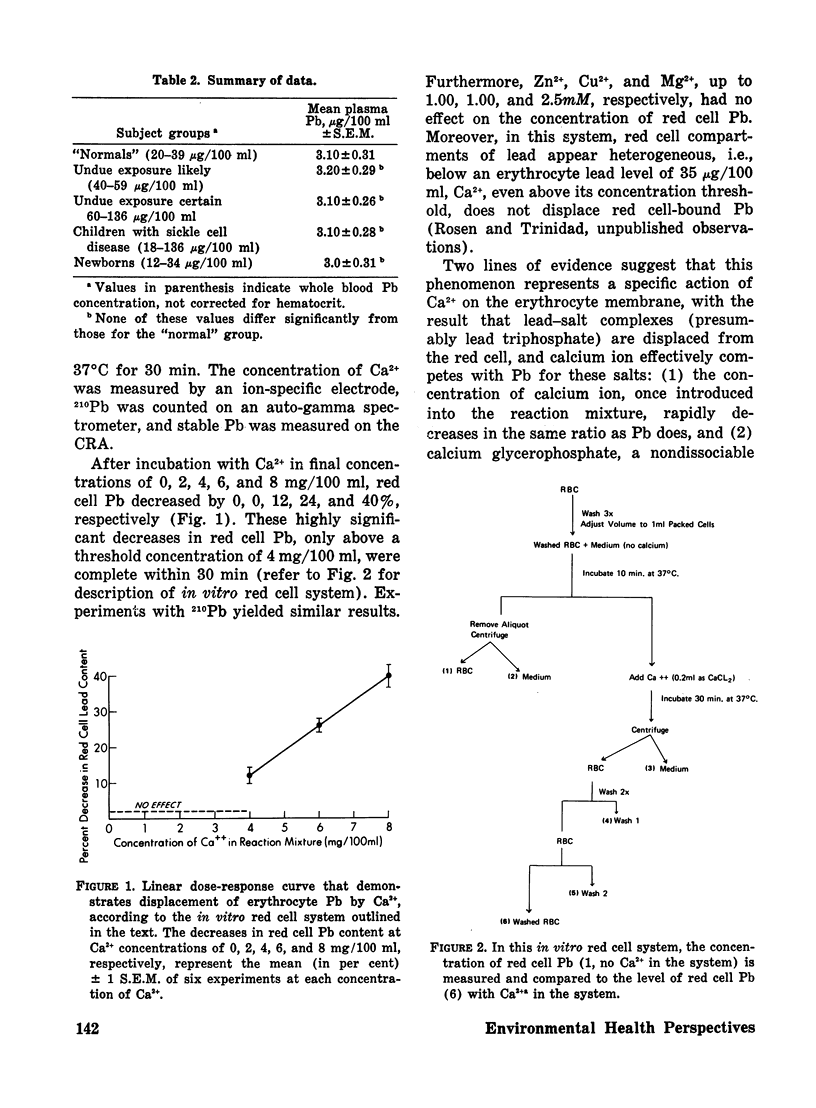

Plasma lead (Pb) levels have been measured in normal and lead-intoxicated children, newborns, and children with sickle cell disease. The results in all groups were contant over a wide range of red cell Pb concentration. These results support the thesis that the red cell represents a large repository for Pb, maintaining plasma Pb concentration within closely defined limits, and that methods other than measurements of plasma Pb will be necessary to uncover a presumably dynamic transport system between red cell and plasma. Indeed, we have demonstrated in vitro that ionized calcium (Ca2+) lowers red cell Pb content according to a linear dose–response curve. Ca2+ may thereby control Pb transport from red cell to plasma, and fluctuations in the concentration of Ca2+ in serum and extracellular fluid may influence the toxic activities of Pb. In bone organ culture, changes in the concentration of Ca2+ and phosphate in the medium alter the release of previously incorporated 210Pb from fetal rat bones in response to parathyroid hormone (PTH). Therefore, both PTH and the ionic milieu of the medium apparently regulate bone Pb metabolism.

We would expect that understanding further the dynamics of Pb transport in plasma and bone may lead to a more exact definition of the real hazards of low level Pb toxicity in children.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BUTT E. M., NUSBAUM R. E., GILMOUR T. C., DIDIO S. L., SISTER MARIANO TRACE METAL LEVELS IN HUMAN SERUM AND BLOOD. Arch Environ Health. 1964 Jan;8:52–57. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1964.10663631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARKSON T. W., KENCH J. E. Uptake of lead by human erythrocytes in vitro. Biochem J. 1958 Jul;69(3):432–439. doi: 10.1042/bj0690432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly R. O., Pybus J. Measurement of lead in blood and urine by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Clin Chem. 1969 Jul;15(7):566–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer R. A. Lead toxicity: a problem in environmental pathology. Am J Pathol. 1971 Jul;64(1):167–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire M. S., Angle C. R. Air lead: relation to lead in blood of black school children deficient in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Science. 1972 Aug 11;177(4048):520–522. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4048.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASSOW H., ROTHSTEIN A., CLARKSON T. W. The general pharmacology of the heavy metals. Pharmacol Rev. 1961 Jun;13:185–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON M. J., KARPINSKI F. E., Jr, BRIEGER H. The concentration of lead in plasma, whole blood and erythrocytes of infants and children. Pediatrics. 1958 May;21(5):793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. F. The microdetermination of blood lead in children by flameless atomic absorption: the carbon rod atomizer. J Lab Clin Med. 1972 Oct;80(4):567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. F., Zarate-Salvador C., Trinidad E. E. Plasma lead levels in normal and lead-intoxicated children. J Pediatr. 1974 Jan;84(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]