Abstract

α-Tocopherol is synthesized exclusively in oxygenic phototrophs and is known to function as a lipid-soluble antioxidant. Here, we report that α-tocopherol also has a novel function independent of its antioxidant properties in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The photoautotrophic growth rates of wild type and mutants impaired in α-tocopherol biosynthesis are identical, but the mutants exhibit elevated photosynthetic activities and glycogen levels. When grown photomixotrophically with glucose (Glc), however, these mutants cease growth within 24 h and exhibit a global macronutrient starvation response associated with nitrogen, sulfur, and carbon, as shown by decreased phycobiliprotein content (35% of the wild-type level) and accumulation of the nblA1-nblA2, sbpA, sigB, sigE, and sigH transcripts. Photosystem II activity and carboxysome synthesis are lost in the tocopherol mutants within 24 h of photomixotrophic growth, and the abundance of carboxysome gene (rbcL, ccmK1, ccmL) and ndhF4 transcripts decreases to undetectable levels. These results suggest that α-tocopherol plays an important role in optimizing photosynthetic activity and macronutrient homeostasis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Several lines of evidence indicate that increased oxidative stress in the tocopherol mutants is unlikely to be the underlying cause of photosystem II inactivation and Glc-induced lethality. Interestingly, insertional inactivation of the pmgA gene, which encodes a putative serine-threonine kinase similar to RsbW and RsbT in Bacillus subtilis, results in a similar increase in glycogen and Glc-induced lethality. Based on these results, we propose that α-tocopherol plays a nonantioxidant regulatory role in photosynthesis and macronutrient homeostasis through a signal transduction pathway that also involves PmgA.

α-Tocopherol (vitamin E) is a lipid-soluble, organic molecule that is only synthesized by oxygen-evolving phototrophs, including some cyanobacteria and all green algae and plants (Threlfall and Whistance, 1971; Collins and Jones, 1981; Sakuragi and Bryant, 2006). The conservation of α-tocopherol synthesis during the evolution of oxygenic photosynthetic organisms suggests that this molecule performs one or more critical functions. Because α-tocopherol is also an essential dietary component, most of our knowledge of tocopherol functions has been obtained from studies in animals, animal cell cultures, and artificial membranes. Studies in these systems have shown that tocopherols scavenge and quench various reactive oxygen species and lipid oxidation by-products, which would otherwise propagate lipid peroxidation chain reactions in membranes (Kamal-Eldin and Appelqvist, 1996). In addition to these antioxidant functions, several other functions have been reported in mammals. These functions, which are independent of the antioxidant activity of tocopherols and are termed nonantioxidant functions, include transcriptional regulation and modulation of signaling pathways (Chan et al., 2001; Azzi et al., 2002; Ricciarelli et al., 2002; Rimbach et al., 2002).

Tocopherol functions have not yet been clearly defined in oxygenic phototrophs, but it is believed that they likely include some or all of the functions reported in animals, as well as other functions possibly specific to photosynthetic organisms. For example, recent studies with tocopherol-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) demonstrated that tocopherols provide protection against propagation of lipid peroxidation in dormant and germinating seeds and thus are essential for seed longevity and seedling development (Sattler et al., 2004). α-Tocopherol has been proposed to protect PSII under high light-induced oxidative stress conditions in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Trebst et al., 2002). Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that tocopherol-deficient mutants of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 grow poorly when challenged with oxidative stress induced by the combination of polyunsaturated fatty acids and high light illumination (Maeda et al., 2005). Therefore, it seems clear that an antioxidant role of α-tocopherol is conserved among the oxygenic phototrophs.

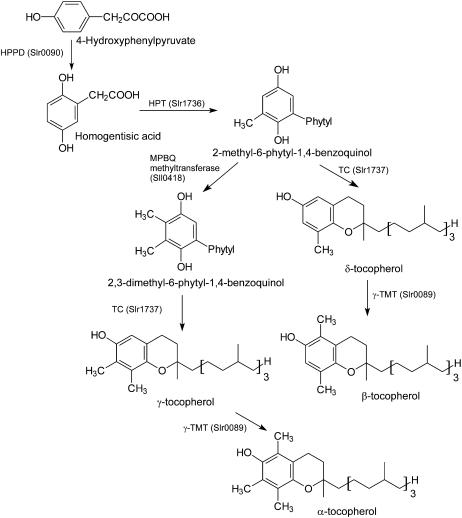

The biosynthesis of α-tocopherol in cyanobacteria occurs as shown in Figure 1. Insertional inactivation of the genes encoding each enzyme of the pathway has resulted in a series of mutants in which the content and composition of tocopherol species vary. For example, the slr0089 mutant accumulates only γ-tocopherol (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998), the sll0418 mutant accumulates 30% of the wild-type level of α-tocopherol and a small amount of β-tocopherol (Shintani et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2003), whereas the slr1736 mutant lacks all tocopherols (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001). In light of the established antioxidant activity of α-tocopherol, one would expect that a loss or reduction of α-tocopherol would lead to an obvious phenotypic difference between the wild-type and mutant strains. Intriguingly, however, the tocopherol-deficient slr1736 mutant was reported to grow similarly to the wild type under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001). These results suggest that α-tocopherol is dispensable for the survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under the conditions tested (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001).

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway for α-tocopherol in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. HPPD, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase; HPT, homogentisate phytyltransferase; MPBQ MT, 2-methyl-6-phytyl-1,4-benzoquinone methyltransferase; TC, tocopherol cyclase; γ-TMT, γ-tocopherol methyltransferase.

In contrast to the results of these previous studies, by reconstructing a series of tocopherol mutants in an isogenic wild-type background, we show here that α-tocopherol is essential for the normal physiology of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Tocopherol mutants exhibited enhanced photosynthetic activities when grown under photoautotrophic conditions, whereas they lost photosynthetic activity after 24 h and were unable to grow under photomixotrophic conditions (in Glc-containing media). These results demonstrate that α-tocopherol is essential for the survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic conditions and suggest a role for α-tocopherol in the regulation of photosynthesis in this cyanobacterium. Further analyses led to the conclusion that oxidative stress is not the major cause of the lethality in cells grown photomixotrophically and that α-tocopherol plays a regulatory role in photosynthesis and macronutrient metabolism in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 that is independent of its antioxidant properties.

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of Isogenic Tocopherol Mutants under Photoautotrophic Conditions

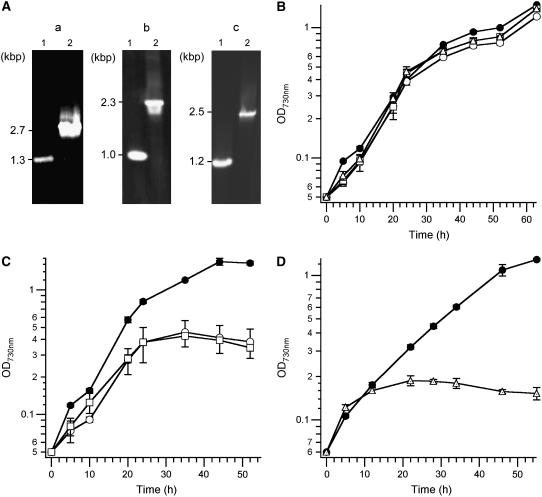

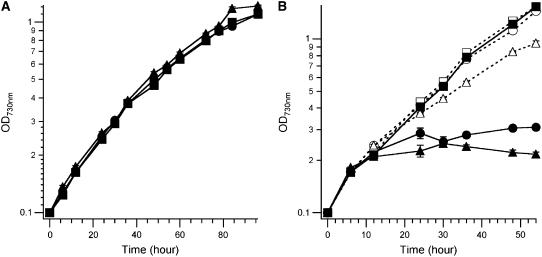

Isogenic mutants deficient in tocopherol biosynthesis were constructed in our laboratory wild-type strain (see “Materials and Methods”). Genomic DNAs extracted from each of the previously isolated tocopherol-deficient mutants (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Shintani et al., 2002) were used for transformation, and the resulting mutants were selected under photoautotrophic growth conditions on the basis of their resistance to kanamycin. Complete segregation of each mutant allele was confirmed by PCR analysis (Fig. 2A). Table I shows the tocopherol content of each homozygous mutant. The tocopherol content of the mutants was similar to that reported previously and further confirmed the targeted gene inactivations (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Cheng et al., 2003). The growth rates of the wild type and mutants were indistinguishable under photoautotrophic growth conditions in liquid B-HEPES medium with 3% (v/v) CO2 at various light intensities (Fig. 2B, 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1; ≤5 and 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1, data not shown). The data demonstrate that α-tocopherol is not required for the growth of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photoautotrophic conditions, which is consistent with previous studies (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Dähnhardt et al., 2002; Maeda et al., 2005).

Figure 2.

Isolation and growth characterization of tocopherol mutants. A, PCR analysis of the genomic DNA extracted from newly isolated tocopherol mutants selected in the absence of Glc. Lanes 1 and 2 in each image show PCR products amplified from the wild-type and mutant genomic DNA templates, respectively. The DNA fragments amplified from the mutant templates using oligonucleotide primers to slr0089 (a), sll0418 (b), and slr1736 (c) loci (see “Materials and Methods”) are 1.3 kb longer than those from the wild-type template because of the insertion of the aphII cassette encoding resistance to kanamycin. B, Growth curves of the wild type and tocopherol mutants at 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 under photoautotrophic conditions. C and D, Growth curves of the wild type and tocopherol mutants at 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 under photomixotrophic conditions. Black circles indicate the wild-type strain; white squares, triangles, and circles indicate the authentic slr1736, sll0418, and slr0089 mutant strains, respectively. The data shown for each strain are averages of three independent cultures; se bars are shown.

Table I.

Tocopherol content of wild type and newly isolated tocopherol mutants

All values shown are averages and ses for at least three independent measurements, except for slr0089, for which the values are based on a single measurement (% values are expressed relative to wild type as 100%). N.D., Not detectable.

| Tocopherol Content

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Tocopherol | β-Tocopherol | γ-Tocopherol | δ-Tocopherol | Total | % | |

| pmol OD730−1nm mL−1 | ||||||

| Wild type | 80.5 ± 6.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | N.D. | 86.4 ± 5.4 | 100 |

| slr0089− | N.D. | N.D. | 8.4 | N.D. | 8.4 | 9.7 |

| slr0418− | 27.2 ± 3.7 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | N.D. | 30.3 ± 4.1 | 35 |

| slr1736− | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0 |

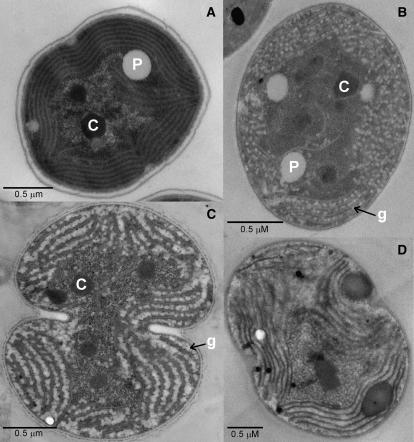

The impact of tocopherol deficiency on photosynthesis was investigated in cells grown under photoautotrophic conditions. The oxygen evolution rates for whole cells were measured to assess the PSII activities of the wild-type and tocopherol mutant strains. Each mutant showed an elevated oxygen evolution rate, which was 17% to 32% higher than that of the wild type (Table II). Analyses of the total cellular sugar content of cells, including all sugar residues found in, for example, lipopolysaccharides, nucleic acids, glycoproteins, and glycogen, revealed that the slr1736 mutant contained 160% of the total sugar level of the wild type when cells were grown photoautotrophically (Table III). In thin-section electron micrographs examined by transmission electron microscopy, the space between thylakoid membranes appeared electron dense and, at most, very small glycogen granules were present in wild-type cells grown under photoautotrophic conditions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the spaces between the thylakoid membranes of the slr1736 mutant under photoautotrophic conditions were filled with very large glycogen granules (large, electron-transparent oval objects; Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that the tocopherol mutants possess elevated photosynthetic activities and accumulate elevated amounts of fixed carbon as glycogen when grown under photoautotrophic conditions.

Table II.

Oxygen evolution activities of wild type and the tocopherol mutants grown under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions for 24 h at 3% CO2 (v/v), 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 32°C in B-HEPES medium

All values shown are averages and ses for at least four independent measurements. N.D., Not detectable.

| O2 Evolution

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Photoautotrophic Conditions | Photomixotrophic Conditions | |

| μm O2 h−1 OD730−1nm | ||

| Wild type | 875 ± 146 | 1,096 ± 12 |

| slr0089− | 1,158 ± 129 | N.D. |

| sll0418− | 1,027 ± 80 | N.D. |

| slr1736− | 1,065 ± 45 | N.D. |

Table III.

Relative sugar content of the wild type and slr1736 and pmgA mutants

Cells were grown in the absence and in the presence of Glc for 24 h at 3% CO2 (v/v), 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 32°C in B-HEPES medium. Equal cell numbers were used for the sugar analysis as described in “Materials and Methods.” All values shown are averages of three independent measurements and are expressed as relative to the average value obtained for the wild type under photoautotrophic conditions.

| Photoautotrophic Conditions | Photomixotrophic Conditions | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.00 ± 0.0761 | 2.23 ± 0.342 |

| slr1736− | 1.60 ± 0.134 | 5.07 ± 0.168 |

| pmgA− | 2.18 ± 0.465 | 4.34 ± 0.189 |

Figure 3.

Thin-section electron micrographs of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strains. A, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 wild type. B, slr1736 mutant grown under photoautotrophic conditions. C, Wild type. D, slr1736 mutant grown under photomixotrophic conditions for 24 h. Letters C, P, and g indicate carboxysomes, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate, and glycogen granules, respectively. Cells were grown in B-HEPES40 medium, pH 7.0, at 1% (v/v) CO2 and 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

Tocopherol Mutants Are Sensitive to Glc

Cells grown under photoautotrophic conditions were diluted into fresh B-HEPES medium containing 5 mm Glc, and growth was monitored under photomixotrophic conditions. The mutants grew similarly to the wild type during the initial 12 to 24 h, but all mutants stopped growing after about 24 h in the presence of Glc (Fig. 2, C and D). After 72 h, the mutants had completely lost viability and could not form colonies even on Glc-free medium (data not shown). The ultrastructure of the slr1736 mutant cells was dramatically different from that of the wild type when both were grown photomixotrophically. The thylakoid membrane surfaces of the mutant appeared smoother than those of the wild type, and numerous electron-dense oval objects, whose biochemical nature is not yet known, can be seen between thylakoid membranes (compare Fig. 3, C and D). Under these conditions, the PSII activity in the mutant cells was completely lost by 24 h, whereas the wild type maintained similar PSII activity during the course of measurements (Table II). Furthermore, in the slr1736 mutant grown under photomixotrophic conditions, no carboxysomes were detectable in thin-section micrographs (see example in Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that α-tocopherol is essential for survival as well as for maintenance of PSII activity and carboxysomes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic conditions.

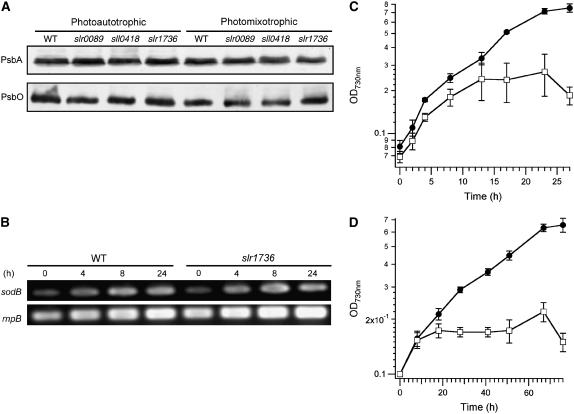

Oxidative Stress Is Unlikely to Be the Cause of Glc Lethality in Tocopherol Mutants

Light-dependent inactivation of photosynthesis, termed photoinhibition, is often observed under a variety of environmental stresses, including high-intensity light (Allakhverdiev et al., 1999; Hideg et al., 2000; Trebst et al., 2002; for review, see Aro et al., 1993, and refs. therein). Under such conditions, the PsbA protein, a polypeptide that forms a subunit of the PSII core complexes, is rapidly degraded and PSII activity is lost. Given the established role of α-tocopherol as an antioxidant and the report that it protects PSII from photoinhibition in C. reinhardtii (Trebst et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the altered photosynthetic activities and growth capacities in the tocopherol mutants under photomixotrophic conditions resulted from elevated oxidative stress due to the loss of α-tocopherol. However, immunologically detectable PsbA protein levels were essentially identical for the wild type and mutants grown both photoautotrophically and photomixotrophically (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the level of immunologically detectable PsbO, a 33-kD protein closely associated with the tetra-manganese cluster of the PSII oxygen evolution complex (Ferreira et al., 2004), was also essentially identical for the wild-type and mutant cells grown both photoautotrophically and photomixotrophically (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that inactivation of PSII in the tocopherol mutants is not due to damage and degradation of the PsbA and PsbO proteins.

Figure 4.

Glc sensitivity in the tocopherol mutants is independent of light levels and is not likely to be due to elevated oxidative stress. A, Immunoblotting analysis for the PsbA (D1) and PsbO proteins. B, Time-course RT-PCR analysis of the sodB transcript in whole cells of wild type and tocopherol mutants grown under photoautotrophic (0 h) and photomixotrophic (4–24 h) conditions at 32°C, 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, with 3% (v/v) CO2. C and D, Growth curves under photomixotrophic conditions (C) under high light (300 μmol photons m−2 s−1) and (D) low light conditions (approximately 5 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Black and white symbols indicate the wild type and the slr1736 mutant, respectively. Proteins from equal amounts of cells (10 μL of cell suspension with OD730 nm = 100) were loaded for each lane (A). Equal amounts of RNA were used as templates for RT-PCR (B). RT-PCR amplification of the housekeeping rnpB RNA was used as the positive control. PCR amplification of the rnpB transcripts without the reverse transcription step did not result in product formation (data not shown).

Expression of the sodB gene, encoding superoxide dismutase, is known to increase severalfold in response to the presence of various reactive oxygen species, and sodB transcripts or SodB are often used as markers for oxidative stress (Hihara et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2002; Ushimaru et al., 2002). Similar and low levels of sodB transcripts were detected in the wild-type and slr1736 mutant cells grown photoautotrophically (Fig. 4B, 0 h). Following a shift to photomixotrophic growth conditions, sodB transcript levels increased gradually and similarly in both the wild type and the slr1736 mutant (Fig. 4B, at 4–24 h). These results indicate that the slr1736 mutant is unlikely to be experiencing oxidative stress beyond that which occurs in wild-type cells. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, C and D, the cessation of growth observed for the tocopherol mutants under photomixotrophic conditions occurs independently of light intensity within the range from approximately 5 μmol photons m−2 s−1 to 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Taken together, these results are not consistent with the hypothesis that oxidative stress causes the inactivation of PSII and growth inhibition observed for the tocopherol mutants under photomixotrophic conditions.

Effect of pH on Glc-Induced Lethality

It is noteworthy that the effect of Glc was dependent on the pH value of the growth medium. The pH in standard B-HEPES medium typically shifted within 48 h from a value of 8.0 to a value between 7.0 and 7.3 due to the supply of 3% CO2 (v/v). Therefore, the possibility that pH influences the Glc-induced lethality was tested using a modified B-HEPES medium (B-HEPES40, containing 40 mm HEPES) that maintained the pH of the culture within ±0.1 pH units for the duration of the growth experiment. Under photoautotrophic conditions, the mutants grew similarly to the wild type at all pH values, indicating that the pH shift has little impact on mutants under these conditions (Fig. 5A). Under photomixotrophic conditions, however, the mutants grew similarly to the wild type at pH 8.0 and 7.6, whereas their growth stopped after 24 h at pH 7.2 and below (Fig. 5A). The PSII activity of the slr1736 mutant was higher than the wild type at all pH values under photoautotrophic growth conditions, consistent with the results presented in Table II. In contrast, under photomixotrophic conditions, PSII activity was pH dependent and completely lost at pH 7.0 and below (Fig. 5B). These results demonstrate that Glc sensitivity and PSII inactivation of tocopherol mutants are pH dependent and occur at approximately pH 7.2 and below.

Figure 5.

pH-dependent Glc-sensitive phenotype of the tocopherol mutants. A, Cultures of the indicated strains were grown under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions at 1% CO2 (v/v), 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 32°C in B-HEPES40 medium (see “Materials and Methods”). B, PSII-dependent oxygen evolution rates in the wild-type (black symbols) and slr1736 mutant (white symbols) cells grown under photoautotrophic (circles) and photomixotrophic (squares) conditions.

Glc metabolism leads to the production of NAD(P)H, which feeds electrons into the membrane electron transport chains, driving generation of the membrane electrochemical potential and, as a result, ATP synthesis. This is accompanied by an alkalization of the cytoplasm (Ryu et al., 2004). It has been reported that the cytoplasmic pH value of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is neutral or slightly alkaline (pH 6.9–7.5), depending on growth conditions (Katoh et al., 1996). Therefore, it was hypothesized that the combination of the neutral medium pH and increased intracellular pH due to Glc import and metabolism led to a compromised membrane electrochemical potential, thereby abating ATP synthesis and growth in the tocopherol mutant. This possibility was tested by using electron transport chain inhibitors to disrupt electron transport and hence the development of the membrane electrochemical potential. 3-(3′,4′-Dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea blocks the input of electrons into the photosynthetic electron transport chain by inhibiting PSII activity; methyl viologen withdraws electrons from the membrane electron transport chain on the acceptor side of PSI, whereas cyanide inhibits cytochrome c oxidase. Regardless of the inhibitors used, the slr1736 mutant showed similar Glc-induced lethality as observed in the absence of the inhibitors (data not shown). These results suggest that Glc toxicity is probably not associated with increased electron flux through the electron transport chain or with an altered membrane potential.

Altered Macronutrient Metabolism in Tocopherol Mutants

How does Glc cause the death of the tocopherol mutants if not by means of oxidative stress or by a modification of electron flux through the electron transport chain? As shown above, under photoautotrophic conditions, the tocopherol mutants exhibited an enhanced photosynthetic activity and elevated total sugar content (Fig. 3B; Table III). We hypothesized that such elevation of the intracellular carbon flux would alter the balance between carbon and other macronutrients and that Glc metabolism would exacerbate this metabolic imbalance, perhaps to a level that could impair growth.

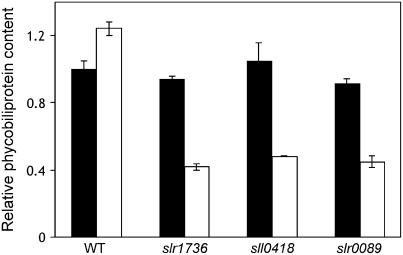

It is noteworthy that the tocopherol mutants appeared pale and chlorotic (greenish-yellow) when grown under photomixotrophic conditions. In cyanobacteria, chlorosis is often associated with macronutrient deprivation, such as nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, iron, and phosphate starvation, because of a rapid degradation of phycobiliproteins (PBPs), light-harvesting antenna proteins that can serve as a reserve of fixed carbon and nitrogen (for review, see Grossman et al., 1994). Analysis of the PBP content revealed that tocopherol mutants contained only 35% of the wild-type level of PBPs after 24 h under photomixotrophic conditions (Fig. 6). Under these conditions, the abundance of the cpcA transcript, which encodes the α-subunit of phycocyanin, also decreased to undetectable levels (Fig. 7A).

Figure 6.

PBP content in the wild type and tocopherol mutants. The wild type and slr1736, sll0418, and slr0089 mutants were grown for 24 h under photoautotrophic (black columns) and photomixotrophic (white columns) conditions at 1% (v/v) CO2, 32°C, pH 7.0, and 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The data shown for each strain are averages of six independent measurements; se bars are shown.

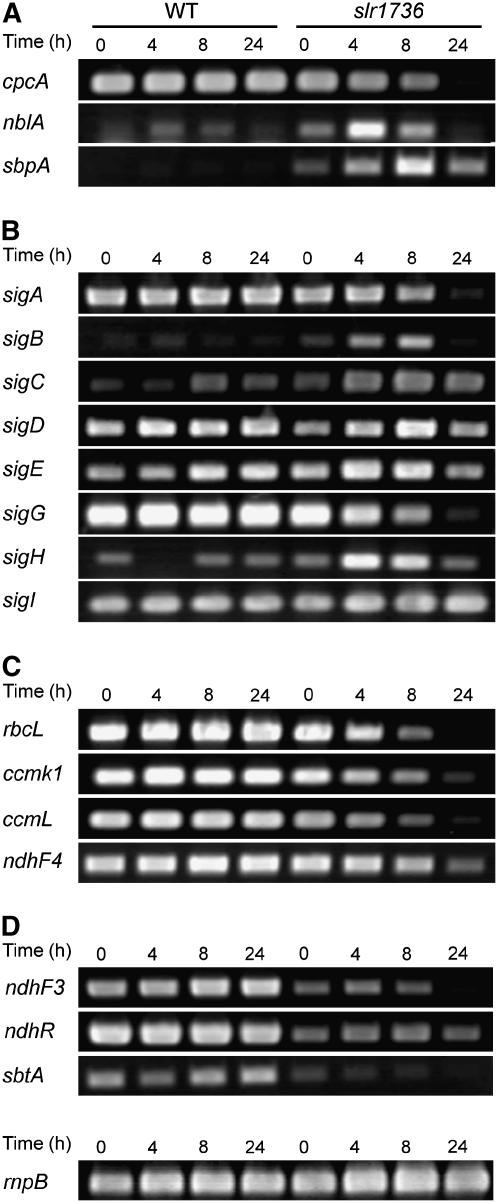

Figure 7.

Time-course RT-PCR analysis of metabolic genes in the wild type and slr1736 mutant grown at pH 7.0. Cells were grown under photoautotrophic (shown at 0 h) and photomixotrophic conditions for 4, 8, and 24 h, at 1% (v/v) CO2, 32°C, pH 7.0, and 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

The nblA operon, which comprises the nblA1 and nblA2 genes, encodes proteins essential for the regulation of PBP degradation (Baier et al., 2004), whereas the sbpA transcript encodes an inducible high-affinity, periplasmic sulfate-binding protein (Laudenbach and Grossman, 1991). The nblA and sbpA transcripts have previously been shown to accumulate in response to nitrogen and sulfate limitation, respectively, in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Laudenbach and Grossman, 1991; Collier and Grossman, 1994; Richaud et al., 2001). Under photoautotrophic growth conditions, the slr1736 mutant accumulated slightly higher levels of these transcripts in comparison to the wild type (Fig. 7A). Under photomixotrophic growth conditions, the slr1736 mutant accumulated substantially higher levels of the nblA and sbpA transcripts after 4 h (Fig. 7A). These data suggest that the slr1736 mutant is sensing and responding to macronutrient stress and that this stress is greatly accentuated under photomixotrophic conditions. One response is increased PBP degradation in the slr1736 mutant under photomixotrophic conditions.

It is known that the expression of alternative sigma factors is induced in response to various stresses, including macronutrient limitation for carbon (sigB and sigH; Caslake et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2004) and nitrogen (sigE; Muro-Pastor et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 7B, the transcript levels of these sigma factors were indeed altered in the slr1736 mutant. For example, the transcript levels of sigB, sigC, and sigE in the slr1736 mutant appeared slightly higher than those of the wild-type control under photoautotrophic growth conditions, and they increased further (by 4 h) in response to Glc treatment (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that the tocopherol mutants are experiencing and transcriptionally responding subtly to macronutrient starvation under photoautotrophic growth conditions and indicate that they are experiencing severe macronutrient starvation related to carbon and nitrogen under photomixotrophic growth conditions. The transcript level for sigI in the slr1736 mutant did not vary significantly from the wild-type control, whereas sigD transcript levels for the mutant and the wild type were highly variable and not reliably reproducible. Interestingly, transcript levels of sigA and sigG in the slr1736 mutant gradually decreased to undetectable levels under photomixotrophic growth conditions. sigA and sigG have been shown to be essential for the survival of this cyanobacterium (Caslake and Bryant, 1996; Huckauf et al., 2000). Therefore, these results indicate that the substantial reduction in the sigA and sigG transcripts combined with the severe macronutrient starvation response led to the cessation of growth in the tocopherol mutants under photomixotrophic growth conditions at pH 7.0.

Transcript Levels of Inorganic Carbon Metabolism Genes

Given the dramatic differences in carbon assimilation between the tocopherol mutants and wild type under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions (Fig. 3; Table III), the abundance of genes involved in inorganic carbon (Ci) metabolism was also investigated by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. In the slr1736 mutant, the transcript levels of carboxysome genes, including rbcL, ccmK1, and ccmL (encoding the large subunit of Rubisco [Pierce et al., 1989] and carboxysome shell proteins [Price et al., 1993], respectively), were identical to those in the wild type under photoautotrophic growth conditions. In contrast, these transcripts gradually decreased to undetectable levels in the slr1736 mutant under photomixotrophic growth conditions, whereas those in the wild type were unaffected (Fig. 7C). As shown by electron micrographs (Fig. 3D), these results are consistent with the loss of carboxysomes in the slr1736 mutant under photomixotrophic growth conditions in the slr1736 mutant. Similarly, the transcript levels of ndhF4, encoding a subunit of the constitutive low-affinity CO2 uptake transporter (Shibata et al., 2001), were not affected under photoautotrophic growth conditions, whereas they gradually decreased to undetectable levels under photomixotrophic conditions in the slr1736 mutant. ndhF3, ndhR, and sbtA encode a subunit of the low CO2-inducible high-affinity CO2 uptake complex, a repressor of ndhF3, and the sodium-dependent bicarbonate transporter, respectively (Klughammer et al., 1999; Shibata et al., 2001, 2002). The transcript levels of these genes were constitutively lower in the slr1736 mutant as compared to the wild type under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 7D). These results demonstrate that the abundance of Ci gene transcripts is differentially regulated in the slr1736 mutant as compared with the wild type.

A pmgA Mutant Also Shows pH-Dependent Lethality under Photomixotrophic Growth Conditions

A previous study identified the pmgA gene as a locus responsible for the survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic growth conditions (Hihara and Ikeuchi, 1997). Although the underlying mechanism is not completely understood, pmgA has been suggested to play a role in the regulation of Glc metabolism and photosynthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Hihara and Ikeuchi, 1997). Therefore, a pmgA mutant was constructed in the same wild-type genetic background as the tocopherol mutants (see “Materials and Methods”), and the growth of this mutant was compared to the wild type and the slr1736 mutant under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic growth conditions at both pH 7.0 and 8.0. Under photoautotrophic conditions at both pH values, the pmgA mutant grew similarly to both the wild type and the slr1736 mutant (Fig. 8A). Under photomixotrophic growth conditions at pH 7.0, growth of the pmgA mutant ceased by 24 h, whereas it continued to grow at pH 8.0 (Fig. 8B). This pH-dependent growth defect was identical to that observed for the slr1736 mutant under photomixotrophic conditions (Fig. 8B). Previously, the pmgA mutant was also shown to have higher photosynthetic activity under photoautotrophic conditions (Hihara and Ikeuchi, 1998), suggesting that, like the slr1736 mutant, the pmgA mutant possesses enhanced photosynthetic capacity under photoautotrophic conditions. Therefore, total sugar content of the pmgA mutant was measured under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions. The pmgA mutant accumulated twice as much total sugar as the wild type under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic growth conditions (Table III), which is very similar to the results observed for the slr1736 mutant (Table III; see above). The striking similarities between the slr1736 and pmgA mutants lead us to propose that α-tocopherol and PmgA may function in the same signal transduction pathway and participate in the regulation of the photosynthetic activity and macronutrient homeostasis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803.

Figure 8.

Growth analysis of the pmgA mutant. Growth curves (A) determined under photoautotrophic conditions at pH 7.0 and (B) under photomixotrophic conditions at pH 7.0 (black symbols with solid lines) and pH 8.0 (white symbols with dotted lines) are shown. Squares, circles, and triangles represent the wild type, slr1736, and pmgA mutants, respectively. The growth curves recorded at pH 8.0 in the absence of Glc coincided with those at pH 7.0 (data not shown). Cells were grown in B-HEPES40 medium, pH 7.0, 1% (v/v) CO2, 32°C, 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, at 32°C. The data shown for each strain are averages of three independent cultures; se bars are shown.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that tocopherol mutants are sensitive to Glc at pH values below approximately 7.4 and are unable to grow under photomixotrophic conditions after 24 h (Fig. 2, C and D). These results are markedly different from the results reported in a previous study in which the tocopherol mutants grew similarly to the parental wild-type strain under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions (Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001). We observed that all of the previously isolated tocopherol mutants (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Shintani et al., 2002) showed colony morphologies that are highly variable with respect to their size and pigmentation when grown under photomixotrophic conditions (data not shown). Inhomogeneous colony morphology typically indicates genotypic heterogeneity within a given population. It is important to note that these mutants were originally isolated and maintained under photomixotrophic conditions (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Shintani et al., 2002), which we now know to be lethal for tocopherol biosynthetic mutants. Therefore, it is highly plausible that the previously isolated populations of tocopherol mutants contain secondary suppressor mutations that were selected for under continuous photomixotrophic conditions. We conclude that the authentic tocopherol mutants described here are Glc sensitive and that α-tocopherol is essential for survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic growth conditions at pH values below approximately 7.4.

Due to its antioxidant properties in biological membranes, functions of α-tocopherol are typically discussed in connection with oxidative stress (Kamal-Eldin and Appelqvist, 1996). Interestingly, in C. reinhardtii, an 80% reduction in α-tocopherol levels, due to combined herbicide and high light treatments (1,500 μmol photon m−2 s−1), resulted in the complete loss of PSII activity with concomitant degradation of the D1 (PsbA) protein (Trebst et al., 2002). This suggests that α-tocopherol plays an antioxidant role in protecting the structural integrity of PSII during oxidative stress in this green alga. Thus, we initially hypothesized that PSII inactivation in tocopherol mutants under photomixotrophic growth conditions was also related to oxidative stress. However, several lines of evidence indicate that this is not the case. First, the PsbA protein level in tocopherol mutants was not altered, although PSII activity was completely lost (Fig. 4A). Second, the Glc-sensitive phenotype of tocopherol mutants was light independent and occurred at a wide range of light intensities (approximately 5–300 μmol photons m−2 s−1; Fig. 4, C and D). Third, sodB transcript levels, an oxidative stress marker, were identical between the slr1736 and wild type under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 4B). Last, the deleterious effects of Glc on the slr1736, sll0418, and slr0089 mutants were virtually indistinguishable despite the varying compositions and amounts of tocopherols accumulated in each mutant (Table I; Figs. 2, C and D, and 5A). Should α-tocopherol function solely as a bulk antioxidant, an inverse correlation of susceptibility to Glc and tocopherol content would reasonably be expected. This was not observed, however, and therefore we conclude that Glc-induced PSII inactivation and growth inhibition of tocopherol mutants are not associated with oxidative stress or D1-mediated photoinhibition. Instead, we propose that, in addition to protecting Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 membranes from peroxidation (Maeda et al., 2005), α-tocopherol also plays a nonantioxidant role in the survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic growth conditions at pH 7.0.

Nonantioxidant roles of α-tocopherol are not without precedent. Studies in animal systems have demonstrated nonantioxidant roles for α-tocopherol, including modulation of signaling pathways and transcriptional regulation (Chan et al., 2001; Azzi et al., 2002; Ricciarelli et al., 2002). For example, α-tocopherol has been shown to modulate the phosphorylation state of protein kinase Cα in rat smooth-muscle cells by influencing protein phosphatase 2A activity (Ricciarelli et al., 1998). It has also been demonstrated that α-tocopherol affects the expression of genes encoding liver collagen αI, α-tocopherol transfer protein, and α-tropomyosin collagenase (Yamaguchi et al., 2001; Azzi et al., 2002; Rimbach et al., 2002). Similarly, the loss of α-tocopherol in the slr1736 mutant constitutively or conditionally altered the abundance of several transcripts, including those encoding components of Ci, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolism (Fig. 7). Loss of α-tocopherol also resulted in elevated photosynthetic activity in cells grown photoautotrophically as shown by increased PSII activity and total sugar and glycogen content (Tables II and III; Figs. 3B and 5B). These data are consistent with α-tocopherol playing a role in the regulation of photosynthesis and macronutrient metabolism—a role that is independent of its antioxidant properties in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803.

What is the underling mechanism by which α-tocopherol, a small secondary metabolite, could affect such cellular processes on a global scale? In searching for an answer, we focused on the pmgA gene, which was previously shown to be essential for the survival of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under photomixotrophic growth conditions (Hihara and Ikeuchi, 1997). An analysis of conserved domains (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) revealed that the primary structure of PmgA is similar to that of RsbW/RsbT in Bacillus subtilis (E value = 6 × e−25), which is a Ser-Thr kinase that acts in the signal transduction cascade that regulates the activity of SigB, a stress-responsive sigma factor in this bacterium (Price, 2000). The pmgA mutant showed remarkable similarity to the slr1736 mutant under both photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions. These included increased levels of total cellular sugars under both growth conditions (Table III), higher oxygen evolution activity than the wild type under photoautotrophic conditions (Hihara and Ikeuchi, 1998), and nearly identical pH-dependent sensitivity to the presence of Glc (Fig. 8). These combined results demonstrate that both α-tocopherol and PmgA are required for the appropriate regulation of photosynthesis and carbon homeostasis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. One possibility is that α-tocopherol and PmgA are both necessary components of a not yet fully characterized signal transduction cascade whose disruption leads to Glc lethality in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Recent studies have shown that the His kinase Hik31 is involved in Glc sensing and Glc-induced lethality (Kahlon et al., 2006), whereas the His kinase Hik8 is involved in Glc metabolism and heterotrophic growth in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Singh and Sherman, 2005). Alternatively, α-tocopherol may indirectly influence the activities and functions of the regulatory proteins or proteins involved in Glc metabolism, particularly those associated with the membranes, by affecting membrane integrity (Wang and Quinn, 2000). These possibilities remain to be examined in future studies.

Such a control mechanism for optimal activity of photosynthesis is essential for the normal physiology of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. We showed here that the slr1736 mutant accumulated the nblA1-nblA2 and sbpA transcripts slightly higher than the wild type even under photoautotrophic conditions (Fig. 7A), suggesting that the mutant is already perceiving a macronutrient stress response related to nitrogen and sulfur under photoautotrophic conditions. It is important to note that this did not affect the growth rates or the PBP content of the tocopherol mutants, perhaps because this level of stress is moderate and thus tolerated under photoautotrophic conditions. After transfer to photomixotrophic growth conditions, the intracellular carbon flux increased further as exemplified by the increased total sugar content in the tocopherol mutants (Table III). One could imagine this would inevitably exacerbate the altered macronutrient homeostasis in the slr1736 mutant. Indeed, under these conditions, the nblA1-2, sbpA, and sigE transcript levels increased dramatically (Fig. 7, A and B), which parallels the decrease in PBP content and the cpcA transcript level (Figs. 6 and 7A). As a result, the tocopherol mutants showed severe chlorosis and growth defects under these conditions (Fig. 2, C and D).

Interestingly, the elevated photosynthetic rate observed for the tocopherol mutants eventually ceased after cells were transferred to photomixotrophic growth conditions. PSII activity was completely lost, no carboxysomes were detectable, and rbcL and other Ci gene transcript levels decreased substantially by 24 h under these conditions (Table II; Figs. 3D and 7C). It is well documented in higher plants that the activity of photosynthesis is negatively regulated by the accumulation of carbohydrates. One aspect of such regulation is triggered by hexoses and their metabolites, which function as signaling molecules and regulate photosynthetic gene expression (for review, see Koch, 1996; Sheen et al., 1999; and refs. therein). Specifically, in Chenopodium and maize (Zea mays), the addition of Glc induces a large transcriptional down-regulation of rbcS (encoding the small subunit of Rubisco; Krapp et al., 1993; Jang and Sheen, 1994), whereas in Arabidopsis the level of the OE33 transcript, encoding the 33-kD oxygen-evolving protein, is subject to Glc repression (Zhou et al., 1998). Therefore, it is plausible that a functionally analogous sugar repression mechanism exists and regulates Ci gene transcription in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Consistent with these ideas, a Glc-sensitive mutant lacking Hik31 has recently been shown to lack glucokinase activity and, correspondingly, a glucokinase mutant cannot grow in the presence of Glc (Kahlon et al., 2006).

In summary, our efforts in reisolating and characterizing tocopherol mutants under photoautotrophic conditions have yielded new insights into the roles and functions for α-tocopherol in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The results described here demonstrate that α-tocopherol is essential for the normal physiology of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and suggest that, in addition to its role as an antioxidant, α-tocopherol plays a role in regulating photosynthesis and macronutrient homeostasis that is independent of this antioxidant activity. It is important to note that maize and potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants, which are defective in tocopherol cyclase activity and are thus tocopherol deficient, also exhibit large alterations in carbohydrate homeostasis due to impaired sugar metabolism/transport (Provencher et al., 2001; Hofius et al., 2004). Although no biochemical or mechanistic explanation exists for this common phenotype between plants and cyanobacteria, it seems plausible that a function for α-tocopherol in the regulation of macronutrient homeostasis is conserved between the two groups of oxygenic phototrophs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth Conditions and Strains

Isolation of the original slr1736, sll0418, and slr0089 mutants under photomixotrophic growth conditions has been described previously (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Collakova and DellaPenna, 2001; Shintani et al., 2002). A Glc-tolerant wild-type strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Williams, 1988) was used in this study for transformation and isolation of the tocopherol mutants in the absence of Glc (see “Results”). B-HEPES medium, pH 8.0, was used for selection, maintenance, and growth measurements of the wild type and mutants. This medium was prepared by supplementing BG-11 medium (Stanier et al., 1971) with 4.6 mm HEPES-KOH and 18 mg L−1 ferric ammonium citrate. B-HEPES40 medium, a modified B-HEPES medium containing 40 mm HEPES to provide greater buffering strength, was used in some experiments that require greater control of the medium pH during growth. The wild type was maintained on solid B-HEPES medium containing 1.5% (w/v) agar and 5 mm Glc, and the photoautotrophically selected tocopherol mutants were maintained on solid B-HEPES medium containing 1.5% (w/v) agar, 50 μg kanamycin mL−1, and, importantly, no Glc. For determination of growth characteristics, late-exponential phase cultures were diluted into fresh liquid B-HEPES medium to OD730 nm = approximately 0.05 cm−1. The diluted cultures were grown at 32°C with continuous bubbling with air containing 1% or 3% (v/v) CO2. The OD730 nm was monitored to measure growth. The medium was supplemented with 5 mm Glc for photomixotrophic growth conditions. The growth light intensity was 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1, unless otherwise specified.

Construction and Isolation of Mutants

The wild type was transformed with genomic DNA extracted from the previously isolated slr1736, sll0418, and slr0089 mutants (see above). Segregation of mutant alleles from wild-type alleles was carried out in the absence of Glc and in the presence of 50 μg kanamycin mL−1. Segregation was verified by PCR analysis. Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR analysis were as follows: slr1736 forward primer (5′-GGCTTCTCCTACCCGGAATTCTACTTCCTG-3′), slr1736 reverse primer (5′-GCTTTCTAAGTGTACATCTAGACTCCGCCA-3′), sll0418 forward primer (5′-ATGCCCGAGTATTTGCTTCTGCC-3′), sll0418 reverse primer (5′-GCACTGCTTTGAACATACCGAAG-3′), slr0089 forward primer (5′-TCTACCGGAAATTGCCAACTACCA-3′), and slr0089 reverse primer (5′-CCTAGGAGATTGTGGACTTCAA-3′). The pmgA gene was amplified by PCR using forward primer (5′-TTCTCTGTGCCGAAAGCTTCTATG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-CACCATGGTGGCGAATTCAGCC-3′). The amplified DNA fragments were digested with HindIII and EcoRI and ligated with pUC19 that had been digested with the same enzymes. An XbaI fragment of pMS266, containing the aacC1 gene that confers gentamicin resistance, was inserted into the unique SpeI site within the pmgA coding region. The resulting plasmid construct was linearized after digestion with EcoRI and used to transform wild-type Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cells. Transformants were selected on solid medium B-HEPES at pH 8.0 in the presence of 20 μg mL−1 gentamicin at room temperature under moderate light intensity (approximately 50 μE m−2 s−1). PCR analyses of the transformants were performed with the same primer pairs described above.

Oxygen Evolution Measurements

Cells grown under photoautotrophic or photomixotrophic conditions for 24 h were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000g at room temperature and resuspended in a 25 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, to obtain an OD730 nm = 1.0 cm−1. Oxygen evolution was measured immediately after the addition of 1 mm 1,4-benzoquinone and 0.8 mm K3Fe(CN)6 to the cell suspension. The excitation light intensity was approximately 3 mmol photons m−2 s−1. The oxygen concentration was measured polarographically with a Clark-type electrode as described previously (Sakamoto and Bryant, 1998).

Estimation of Relative PBP Content

The relative PBP content of cells was determined by a minor modification of the method of Zhao and Brand (1989). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000g for 6 min and pellets were resuspended in 25 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, to obtain cell suspensions (2 mL) with OD730 nm = 0.5 cm−1. These suspensions (1.0 mL) were heated at 100°C for 1 min. The OD635 nm and OD730 nm were recorded for unheated and heated samples, and the values were then inserted into the following equation: relative PBP content = (ΔOD635 nm − ΔOD730 nm)/OD730 nm·unheated, where ΔOD indicates ODunheated sample − ODheated sample.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Cells were grown under photoautotrophic conditions to the midexponential phase or under photomixotrophic conditions for 24 h, harvested as described above, and resuspended in 25 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, to achieve OD730 nm = 100 cm−1. Cells were disrupted using an equal volume of glass beads and a home-built bead beater; cold cell suspensions were vigorously shaken four times for 30 s, interrupted by 30-s intervals on ice. An aliquot (10 μL) of each sample was mixed with an equal volume of loading buffer; the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 20 min and applied onto a discontinuous SDS-polyacrylamide gel with 10% (w/v) acrylamide in the separating gel as described (Schägger and van Jagow, 1987). Prof. Eva-Mari Aro kindly provided antibodies raised against amino acids 234 to 242 of the PsbA protein of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Prof. Robert Burnap kindly provided antibodies raised against the PsbO protein of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Proteins were detected by immunoblotting by using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's specifications.

Isolation of Total RNA and RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was isolated and purified from cells using the mini-to-midi RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen). The RNA samples were purified again after DNase digestion. The RNAs obtained were adjusted to a final concentration of 50 ng RNA μL−1 and stored at −80°C until used. Transcripts were amplified and detected by using the one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) in the presence of the RNase inhibitor RNAsin (Promega) with target-specific oligonucleotide primers. The sequences of the primers used for each of the indicated genes will be made available upon request.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cells grown under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions for 24 h were harvested and immediately fixed overnight at 4°C in a 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde solution prepared in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. After secondary fixation in a 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide solution in the cacodylate buffer, the cells were stained with uranyl acetate (2% w/v), followed by dehydration in the following concentrations of ethanol: 50% (v/v), 70% (v/v), 90% (v/v), 95% (v/v) ethanol in water followed by two washes in 100% (v/v) ethanol. The samples were then embedded in Spurr's resin and polymerized overnight at 60°C. Thin sections (approximately 50- to 60-nm thickness) were stained with 2% (v/v) uranyl acetate before examination under a JEM 1200 EXII transmission electron microscope (JEOL).

Total Sugar Assay

Cells were harvested as described above and washed and resuspended in distilled water to achieve the same OD730 nm. The total sugar content of each cell suspension was determined by a previously described colorimetric assay (Dubois et al., 1956). The total sugar content was calculated relative to the A435 nm for the wild-type cells grown under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions.

Analysis of Tocopherol Content

The tocopherol content of the wild-type and mutant strains was analyzed as described previously (Cheng et al., 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Eva-Mari Aro (University of Turku, Finland) for providing the PsbA antibodies; Prof. Robert Burnap (Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK) for providing the PsbO antibodies; Prof. Aaron Kaplan (Hebrew University, Jerusalem) for providing unpublished results, comments, and suggestions; and Dr. Paul Straight and Prof. Dan Fraenkel (Harvard Medical School, Boston) for critical comments and suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. MCB–023529 to D.D.P. and MCB–0077586 to D.A.B.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Donald A. Bryant (dab14@psu.edu).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.105.074765.

References

- Allakhverdiev SI, Nishiyama Y, Suzuki I, Tasaka Y, Murata N (1999) Genetic engineering of the unsaturation of fatty acids in membrane lipids alters the tolerance of Synechocystis to salt stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 5862–5867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro E-M, Girgin T, Andersson B (1993) Photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turn over. Biochim Biophys Acta 1143: 113–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi A, Ricciarelli R, Zingg JM (2002) Non-antioxidant molecular functions of α-tocopherol (vitamin E). FEBS Lett 519: 8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier K, Lehmann H, Stephan DP, Lockau W (2004) NblA is essential for phycobilisome degradation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 but not for development of functional heterocysts. Microbiology 150: 2739–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caslake L, Bryant DA (1996) The sigA gene encoding the major sigma factor of RNA polymerase from the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002: cloning and characterization. Microbiology 142: 347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caslake L, Gruber TM, Bryant DA (1997) Expression of two alternative sigma factors of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 is modulated by carbon and nitrogen stress. Microbiology 143: 3807–3818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Monteiro HP, Schindler F, Stern A, Junqueira VB (2001) α-Tocopherol modulates tyrosine phosphorylation in human neutrophils by inhibition of protein kinase C activity and activation of tyrosine phosphatases. Free Radic Res 35: 843–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Sattler S, Maeda H, Sakuragi Y, Bryant DA, DellaPenna D (2003) Highly divergent methyltransferases catalyze a conserved reaction in tocopherol and plastoquinone synthesis in cyanobacteria and photosynthetic eukaryotes. Plant Cell 15: 2343–2356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collakova E, DellaPenna D (2001) Isolation and functional analysis of homogentisate phytyltransferase from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 127: 1113–1124 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JL, Grossman AR (1994) A small polypeptide triggers complete degradation of light-harvesting phycobiliproteins in nutrient-deprived cyanobacteria. EMBO J 13: 1039–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D (1981) Distribution of isoprenoid quinone structural types in bacteria and their taxonomic implications. Microbiol Rev 45: 316–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dähnhardt D, Falk J, Appel J, van der Kooij TAW, Schulz-Friedrich R, Krupinska K (2002) The hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is not required for plastoquinone biosynthesis. FEBS Lett 523: 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F (1956) Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 28: 350–356 [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S (2004) Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science 303: 1831–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AR, Schaefer MR, Chiang GG, Collier JL (1994) The responses of cyanobacteria to environmental conditions, light and nutritions. In DA Bryant, ed, The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 641–675

- Hideg E, Kalai T, Hideg K, Vass I (2000) Do oxidative stress conditions impairing photosynthesis in the light manifest as photoinhibition? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355: 1511–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y, Ikeuchi M (1997) Mutation in a novel gene required for photomixotrophic growth leads to enhanced photoautotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynth Res 53: 243–252 [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y, Ikeuchi M (1998) A novel gene, pmgA, specifically regulates photosystem stoichiometry in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to high light. Plant Physiol 117: 1205–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihara Y, Kamei A, Kanehisa M, Kaplan A, Ikeuchi M (2001) DNA microarray analysis of cyanobacterial gene expression during acclimation to high light. Plant Cell 13: 793–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofius D, Hajirezaei MR, Geiger M, Tschiersch M, Melzer M, Sonnewald U (2004) RNAi-mediated tocopherol deficiency impairs photoassimilate export in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol 135: 1256–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, McCluskey MP, Ni H, LaRossa RA (2002) Global gene expression profiles of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to irradiation with UV-B and white light. J Bacteriol 184: 6845–6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckauf J, Nomura C, Forchhammer K, Hagemann M (2000) Stress responses of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 mutants impaired in genes encoding putative alternative sigma factors. Microbiology 146: 2877–2889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JC, Sheen J (1994) Sugar sensing in higher plants. Plant Cell 6: 1665–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlon S, Beeri K, Ohkawa H, Hihara Y, Murik O, Suzuki I, Ogawa T, Kaplan A (2006) A putative sensor kinase, Hik31, is involved in the response of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 to the presence of glucose. Microbiology 152: 647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal-Eldin A, Appelqvist L (1996) The chemistry and antioxidant properties of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Lipids 31: 671–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh A, Sonoda M, Katoh H, Ogawa T (1996) Absence of light-induced proton extrusion in a cotA-less mutant of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 178: 5452–5455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer B, Sültemeyer D, Badger MR, Price GD (1999) The involvement of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase subunits, NdhD3 and NdhF3, in high-affinity CO2 uptake in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 gives evidence for multiple NHD-1 complexes with specific roles in cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol 32: 1305–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KE (1996) Carbohydrate-modulated gene expression in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47: 509–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp A, Hofmann B, Schafer C, Stitt M (1993) Regulation of the expression of rbcS and other photosynthetic genes by carbohydrates: a mechanism for the “sink regulation” of photosynthesis? Plant J 3: 817–828 [Google Scholar]

- Laudenbach DE, Grossman AR (1991) Characterization and mutagenesis of sulfur-regulated genes in a cyanobacterium: evidence for function in sulfate transport. J Bacteriol 173: 2739–2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Sakuragi Y, Bryant DA, DellaPenna D (2005) Tocopherols protect Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 from lipid peroxidation. Plant Physiol 138: 1422–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro-Pastor AM, Herrero A, Flores E (2001) Nitrogen-regulated group 2 sigma factor from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 involved in survival under nitrogen stress. J Bacteriol 183: 1090–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J, Carlson TJ, Williams JG (1989) A cyanobacterial mutant requiring the expression of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase from a photosynthetic anaerobe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 5753–5757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CW (2000) Protective function and regulation of the general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related Gram-positive bacteria. In G Storz, R Hengge-Aronis, eds, Bacterial Stress Response. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp 179–197

- Price GD, Howitt SM, Harrison K, Badger MR (1993) Analysis of a genomic DNA region from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC7942 involved in carboxysome assembly and function. J Bacteriol 175: 2871–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher LM, Miao L, Sinha N, Lucas WJ (2001) Sucrose export defective1 encodes a novel protein implicated in chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. Plant Cell 13: 1127–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciarelli R, Tasinato A, Clément S, Özer NK, Boscoboinik D, Azzi A (1998) α-Tocopherol specifically inactivates cellular protein kinase Cα by changing its phosphorylation state. Biochem J 334: 243–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciarelli R, Zingg JM, Azzi A (2002) The 80th anniversary of vitamin E: beyond its antioxidant properties. Biol Chem 383: 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richaud C, Zabulon G, Joderr A, Thomas JC (2001) Nitrogen and sulfur starvation differentially affects phycobilisomes degradation and expression of the nblA gene in Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 183: 2989–2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimbach G, Minihane AM, Majewicz J, Fischer A, Pallauf J, Virgli F, Weinberg PD (2002) Regulation of cell signaling by vitamin E. Proc Nutr Soc 61: 415–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J, Song JY, Lee JM, Jeong SM, Chow WS, Choi S, Pogson BJ, Park Y (2004) Glucose-induced expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes in the dark is mediated by cytosolic pH in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem 279: 25320–25325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T, Bryant DA (1998) Growth at low temperature causes nitrogen limitation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Arch Microbiol 169: 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi Y, Bryant DA (2006) Genetic manipulation of quinone biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. In JH Golbeck, ed, Photosystem I: The Plastocyanin:Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, Vol 24. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 205–222

- Sattler SE, Gilliland LU, Magallanes-Lundback M, Pollard M, DellaPenna D (2004) Vitamin E is essential for seed longevity and for preventing lipid peroxidation during germination. Plant Cell 16: 1419–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H, van Jagow G (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166: 368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J, Zhou L, Jang J (1999) Sugars as signaling molecules. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2: 410–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Katoh H, Sonoda M, Ohkawa H, Shimoyama M, Fukuzawa H, Kaplan A, Ogawa T (2002) Genes essential to sodium-dependent bicarbonate transport in cyanobacteria. J Biol Chem 277: 18658–18664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Ohkawa H, Kaneko T, Fukuzawa H, Tabata S, Kaplan A, Ogawa T (2001) Distinct constitutive and low-CO2-induced CO2 uptake systems in cyanobacteria: genes involved in and their phylogenetic relationship with homologous genes in other organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11789–11794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani D, Cheng Z, DellaPenna D (2002) The role of 2-methyl-6-phytyl-benzoquinone methyltransferase in determining tocopherol composition in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett 511: 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani D, DellaPenna D (1998) Elevating the vitamin E content of plants through metabolic engineering. Science 282: 2098–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Sherman LA (2005) Pleiotropic effect of a histidine kinase on carbohydrate metabolism in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and its requirement for heterotrophic growth. J Bacteriol 187: 2368–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier RY, Kunisawa R, Mandel M, Cohen-Bazire G (1971) Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol Rev 35: 171–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall DR, Whistance GR (1971) Biosynthesis of isoprenoid quinones and chromanols. In TW Goodwin, ed, Aspects of Terpenoid Chemistry and Biochemistry. Academic Press, London, pp 357–404

- Trebst A, Depka B, Höllander-Czytko H (2002) A specific role for tocopherol and of chemical singlet oxygen quenchers in the maintenance of photosystem II structure and function in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Lett 516: 156–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushimaru T, Nishiyama Y, Hayashi H, Murata N (2002) No coordinated transcriptional regulation of the sod-kat antioxidative system in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Plant Physiol 159: 805–807 [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Postier BL, Burnap RL (2004) Alterations in global patterns of gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to inorganic carbon limitation and the inactivation of ndhR, a LysR family regulator. J Biol Chem 279: 5739–5751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Quinn PJ (2000) The location and function of vitamin E in membranes (review). Mol Membr Biol 17: 143–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JGK (1988) Construction of specific mutations in photosystem-II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol 167: 766–778 [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi J, Iwamoto T, Kida S, Masushige S, Yamada K, Esashi T (2001) Tocopherol-associated protein is a ligand-dependent transcriptional activator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 285: 295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Brand JJ (1989) Specific bleaching of phycobiliproteins from cyanobacteria and red algae at high temperature in vivo. Arch Microbiol 152: 447–452 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Jang JC, Jones T, Sheen J (1998) Glucose and ethylene signal transduction crosstalk revealed by an Arabidopsis glucose-insensitive mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 10294–10299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]