Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to examine the effects of health care policy on the development of integrated mental health services in England.

Data sources

Drawing largely from a narrative review of the literature on adult mental health services published between January 1997 and February 2003 undertaken by the authors, we discuss three case studies of integrated care within primary care, secondary care and across the primary/secondary interface for people with serious mental illness.

Conclusion

We suggest that while the central thrust of a raft of recent Government policies in England has been towards integration of different parts of the health care system, policy waterfalls and implementation failures, the adoption of ideas before they have been thoroughly tried and tested, a lack of clarity over roles and responsibilities and poor communication have led to an integration rhetoric/reality gap in practice. This has particular implications for people with serious mental health problems.

Discussion

We conclude with suggestions for strategies that may facilitate more integrated working.

Keywords: mental health, integration, health policy

Introduction

Health care services in England have been subject to a series of significant policy imperatives in the past decade. There has been a shift in the theoretical debate around the ways in which healthcare organisations should deliver services to improve quality of care through extending patient choice and access to care and a particular focus on issues of partnership working and integrated care. The debates around the value of integrated care have been rehearsed in many other countries [1, 2] as a model for transforming health care systems, improving efficiency and responding to the multiple needs of patients both within and beyond the field of mental health [3].

This paper explores policy developments around service integration within and between primary care and secondary mental health services in England, and reflects on how far current services have moved beyond policy rhetoric towards the reality of integrated services. We focus on integrated care for people with serious mental illness, a group for whom continuity of care is particularly important [4] and who have limited options and choice to seek care elsewhere if dissatisfied. A seamless, co-ordinated accessible pathway to care is, therefore, arguably more important for mental health service users than many other patients.

The evidence base sources quoted in this paper are largely drawn from a narrative review of the literature on adult mental health services published between January 1997 and February 2003 undertaken by the authors [5]. This has been supplemented by discussions with clinical leaders in the field of adult mental health, particularly in Early Intervention Services where the authors are involved with a national evaluation of services.

The importance of mental health

Serious mental health problems are relatively common. Recent statistics suggest that an estimated one in two hundred people have experienced a psychotic disorder in the past year in the United Kingdom [6] and that approximately three per cent of the population have some form of serious mental illness such as bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia or severe depression [7]. The financial costs of mental illness in England have been estimated at over 77 billion pounds [8], and this figure doubles once quality of life is included alongside costs of care and lost productivity. Indeed, the total cost to the economy of mental health problems is greater than ischemic heart disease, breast cancer and diabetes combined. Mental illness also has a significant impact on the families of those with mental health problems, many of whom act as unpaid carers. Whilst harder to quantify, it has also been argued that mental illness impacts on a nation's social capital through the medium of poverty and social exclusion [9].

Conceptualising integrated health care

Integrated care is, of itself, a nebulous and often poorly defined concept, with different authors emphasising different aspects. Kodner and Spreeuwenberg [10] in this journal have usefully proposed that

integration is a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sector … to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction and system efficiency for patients with complex, long-term problems cutting across multiple services, providers and settings.

Rhodes [11] describes integrated working as a method of overcoming the complexity associated with welfare care, and is characterised by dynamic, flexible and evolving methods of working that rely on horizontal self-governing networks. Notions of horizontal and vertical integration are also important in conceptualising and understanding policy and practice. Horizontal integration refers to the bringing together of professions, services and organisations that operate at similar levels in the care hierarchy. Vertical integration refers to the bringing together of different levels in the one hierarchy.

The conditions required for an integrated approach to mental health can be conceptualised as ways of working that acknowledge the importance of creating a seamless pathway for the patient as they make their way through different parts of the mental health system. From a structural perspective, integrated care goes one step beyond collaboration to co-ordination and often co-location of care. To be sustainable, an integrated approach needs to be underpinned by opportunities for health professionals from different backgrounds to train and learn together. It also depends on good communication across the interface, particularly around criteria for referral and discharge.

The importance of integrated mental health services

As the Kodner and Spreeuwenberg [10] definition of integrated care suggests, the potential benefits of generic integrated approaches are significant for both patients and providers. In the specific context of primary care mental health, Blount [12] suggests there is evidence that an integrated approach to care can improve adherence to medication because it provides a better fit with the often undifferentiated way patients present, increase satisfaction with care and, because of transfer of expertise among team members, can improve providers' skills base in dealing with psychosocial aspects of care. A number of commentators have also suggested that integrated care can be more cost effective [12, 13].

There is also an increasing evidence base for both the central importance of continuity of care for people with serious mental illness [4] and of the misinterpretations and consequences of being lost to follow up [14] which add weight to the arguments for a more integrated approach to mental health care.

People with serious mental health problems are also among the most socially excluded within any society, subject to the interlocking and mutually compounding problems of impairment, discrimination, diminished social roles, unemployment and lack of social networks [15]. They have fewer options and resources than most and many find it problematic to negotiate the complex bureaucracies and range of different agencies involved in mental health. They, therefore, need services that are well integrated at the point of contact and a health care system that makes sense from their perspective, that fits their differing needs at different points in their journey and that adopts a holistic approach to care [16].

The consequences of poorly integrated services

There are a number of costs of poor integration. Perhaps the most extreme cost was reinforced by a series of enquiries into murder cases involving people with mental health problems. The Ritchie report [17], which was the culmination of the inquiry into the killing of Jonathan Zito by Christopher Clunis, who was diagnosed as having schizophrenia, at a London underground station in 1992, highlighted the difficulties inherent in joint working between services, the duplication of effort and indeed the potential for no-one taking ultimate responsibility. The Ritchie Report did not, on the whole, blame individuals and indeed noted that Christopher Clunis was in some sense a victim of the health and social care system since he had spent over 5 years being sent between different facets of the health and welfare service, between hospital, hostels and prison with no overall plan for his care and inadequate supervision for many aspects of the health and social services.

From the patients' perspective, although relatively little has been published on users' views of integrated services, Preston [14] found that many patients felt they had been left in limbo, with poor communication and co-ordination across the interface often to blame. As one of the people interviewed in his study commented:

Separate clinics don't talk to each other or ring each other. I find the whole thing incredible, the length of time it takes: it's just been horrendous, waiting weeks to see a consultant to be told ‘I don't know why you've been referred to me’…It can make you feel very insignificant (1999, p.19).

Case studies of integrated care

Policy background

When New Labour formed the Government in the United Kingdom in 1997, one its main policy focuses was on the ‘modernisation’ of all sectors of Government. This encompassed the promotion of partnership working between different areas of Government and with the voluntary and private sectors, and consultation with patients. Giddens [18] described this new way of working as a ‘third way’ in the delivery of welfare and health care between centralised, bureaucratic planning and marketised, consumerist liberalism. The concept of the ‘third way’ took on particular meaning at this time as it also became associated with the politics of the New Democrats led by Bill Clinton in the United States.

Echoing third way ideals, the Government's first substantive health service White Paper The New NHS: Modern and Dependable [19] stated:

The Government is committed to building on what has worked but discarding what has failed. There will be no return to the old centralised command and control of the 1970s … but nor will there be a continuation of the divisive internal market system of the 1990's … Instead there will be a third way of running the NHS—a system based on partnership (Secretary of State for Health, 1997, p. 10).

However, as the following case studies will demonstrate, there is evidence to suggest that the speed of change and number of significant often paradoxical policy directives are in many ways responsible for the failure of fully integrated services across health care (see Figure 1). We will now examine these policy paradoxes from three different perspectives: integration of services for people with serious mental illness within primary care, secondary care and finally, across the interface between primary and secondary care.

Figure 1.

Policy time line from 1997.

Case study 1: horizontal integration in primary care for people with serious mental illness

One of the main changes heralded in The New NHS [19] was that commissioning would be in the hands of Primary Care Trusts, that is, a new basic organisational unit of the National Health Service covering an average of 100,000 patients set up to manage, commission and also to some extent provide primary care services, instead of fund holding General Practitioners and Health Authorities. However, the policy document on Primary Care Trust formation, Shifting the Balance of Power [20] in 2001 dramatically accelerated the timeframe for their formation. Twelve months later, Shifting the Balance of Power—the next steps [21] gave Primary Care Trusts additional responsibility for commissioning all mental health services. There are now over 300 Primary Care Trusts in England, controlling 75% of the health budget. They have, in effect, become substitute Health Authorities for their geographical areas, but operate from primary care rather than acute care platforms. However, almost as soon as Primary Care Trusts had started to function as independent bodies, the introduction of the new General Medical Services Contract, effective from April 2004 [22] and of practice based commissioning in 2005 [23], led to a further series of fundamental changes in the way in which primary care is delivered (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The NHS structure in England.

The new General Medical Services Contract, which directly affects the 36,000 General Practitioners in the United Kingdom and their patients, is a practice-based contract between the Primary Care Trust and the practice. There are far more centrally driven targets which may theoretically encourage a better quality core service with, for example, points (meaning money) related to the delivery of specific services. It may also help to ensure greater consistency in standards and services. General Practitioners can now decide to offer services at one of three levels: essential services for people with acute and chronic illnesses and which have to be provided by all practices; additional services including maternity and contraceptive services which are being offered by most practices, and enhanced services (which are optional) including specialised care for people with depression.

From the perspective of patients with mental health problems such as severe depression, the new contract means that they may be able to see their regular General Practitioner for the sore throat, but have to go to a different health care setting to discuss their depression if the Primary Care Trust has set up specialised enhanced services for people with depression as part of the enhanced services scheme. Potential outcomes of this new way of providing services include poorer continuity of care, an important part of integrated care, particularly for people with serious mental illness. This policy imperative also reinforces the Cartesian notion of seeing people as having either a physical or a mental health problem.

The advent of primary care practice based commissioning from April 2005 poses an additional potential threat to integrated mental health care. In 1997, when New Labour abolished fund holding, the Government made it clear that that it was keen to see practices given the opportunity to hold indicative budgets to commission a full range of services [19]. The NHS Improvement Plan [24] stated that practices would be able to hold an indicative budget from April 2005 to commission services including community health team assessments, psychological therapies and services from specialised functionalised teams such as early intervention and assertive outreach teams. Potential benefits cited in support of practice based commissioning include an opportunity to offer ‘seamless’ health and social care. However, drawbacks highlighted by Craig et al. [25] include the tension that may be created between the need for strategic planning to underpin sustainable commissioning and the fragmented nature of devolved commissioning to individuals or groups of practice. Unlike many other areas of the National Health Service, it is additionally difficult to attach a price tag to mental health services (indeed mental health services are excluded from the Payment by Results scheme introduced in April 2005 precisely because of this reason). Practice based commissioning also requires consistent quality of service delivery and good quality information about services to be able to offer patients a meaningful choice. Neither of these is as far advanced in mental health services as in other parts of the National Health Service. Whilst the formation of Primary Care Trusts could be seen as a strong driver towards integrated care, the new GP contract and subsequent devolution of commissioning back to individual practices and localities threatens to significantly fragment services particularly for patients with serious mental illness.

Case study 2: horizontal integration—the effect of functionalised mental health teams on integrated secondary care mental health services

Since the 1980s, multi-disciplinary generic Community Mental Health Teams have been the main vehicle for delivering co-ordinated comprehensive community based mental health services [26]. Recently, however, this notion of a generic community mental health team responsible for all aspects of care for people with common mental health problems referred from primary care and also people with serious mental illness and more complex needs has been reassessed. Evidence from evaluations of service models in North America [27] and Australia [28] and successful remodelling of the community mental health services in North Birmingham in the United Kingdom have been influential in the thinking and development of functionalised mental health teams, that is, specialist teams organised to provide for the needs of particular patient groups. This approach has been reinforced by the NSF for Mental Health [29], The NHS Plan [30] and a series of Mental Health Policy Implementation Guides [31] describing the more detailed team structure and functions.

The Guidance on community mental health teams states that ‘Community Mental Health Teams will continue to be the mainstay of the system. Community mental health teams have an important and indeed integral role to play in supporting service users and families in community settings. They should provide the core around which newer service elements are developed’ (2002, p. 3). Although the guidance is not prescriptive about the relationships between Community Mental Health Teams and the newer functionalised teams, it suggests that ‘mutually agreed and documented responsibilities, liaison procedures and in particular transfer procedures need to be in place when crisis resolution, home treatment teams, assertive outreach teams and early intervention teams are being established’ (2002, p. 17). Community Mental Health Teams in future are, therefore, envisaged as the central hub of mental health care, liaising with the more specialised teams as well as with primary care.

These policy pledges, which led to the formation of a series of functionalised teams, look on the surface to encourage more appropriate and focussed care without threatening the horizontal integration of mental health services. However, in practice, they appear to be having a number of paradoxical effects. Emerging evidence from national evaluations of some of the functionalised teams suggest that one unexpected consequence of their introduction is a disintegration of services from the patient's perspective. There are, for example, concerns about the speed with which Early Intervention Services are being developed [32] and commissioned and, indeed, the need for a separate Early Intervention Services at all [33]. Within some Early Intervention Services, evidence from the EDEN study suggests that variable ‘buy in’ to the concept at Primary Care Trust commissioning level has led to problems with releasing funds to develop new teams and downward financial pressures on existing ones. This is turn has led to staff shortages and time constraints and resulted in some teams deciding to reduce the age criteria for admission to services. There has also been insufficient time to develop links with teams who provide out of hours care (between 6 pm and 9 am) and liaise with teams who feed into early intervention services and take over care once the initial period of care by the Early Intervention Service is complete, all of which pose significant threats to patient continuity of care (EDEN early intervention services evaluation project team, personal communication). Effective integrated care requires new teams to have clear lines of communication with existing teams and adequate financial resources, not redistribution of existing monies from more established teams.

Case study 3: vertical integration across the interface

In the United Kingdom, integrated mental health care is most commonly represented as a system of shared care between the primary health care team and secondary care mental health services [34]. In the early 1990s, it was estimated that, at any one time, between 20 and 30 people per 1,000 of the United Kingdom population were being referred to out-patients or to Community Mental Health Teams for further care, and were, therefore, in receipt of shared care [35]. There is little to suggest that the numbers are much different today.

From a policy perspective, shared care has been increasingly mandated since the advent of the New Labour Government in 1997, reflecting the partnership approach within the wider modernisation agenda. Primary care, for example, has specific responsibility for delivering standards two and three of the National Service Framework for Mental Health [29] and is also integrally involved in the delivery of the other five standards with secondary care mental health services. The NHS Plan [30] further underpinned this with over £300 million of investment to help implementation, included specific pledges to create 1,000 new graduate mental health workers to work in primary care and encourage a shared care approach across the interface. There are also negotiations at a national level around formally extending the role of General Practitioners with a special clinical interest, including mental health, who will play a key role in managing people with depression and serious mental illness within appropriate shared care arrangements with secondary care [36]. A range of secondary care policy initiatives are also encouraging shared care. The recent National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidance on schizophrenia includes a series of clinical practice recommendations from developing primary care practice registers for people with schizophrenia, the development of advance directives placed in both primary and secondary care and the development of referral guidelines from primary to secondary care [37].

However, despite this plethora of guidance and new roles to encourage horizontal integration, there is little consistency between Primary Care Trusts in terms of the type of care commissioned between primary care and secondary care mental health services and the advent of Practice Based Commissioning is likely to lead to an even more disparate approaches.

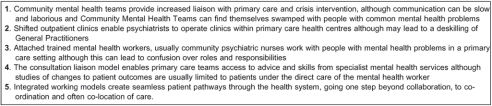

There are currently at least five different models of interface working and little consensus over how integrated care could best be achieved [38]. Each model involves different players and degrees of commitment to the concept of integration. Each attempts to enable communication across the interface and has its own particular strengths and weaknesses (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Models of mental health care at the primary secondary interface.

Other barriers to more integrated care across the primary/secondary care interface include the paucity of formal training in mental health for General Practitioners. A recent survey found that only one third of General Practitioners had received any mental health training in the last 5 years, while 10% expressed concerns about their training or skills needs in mental health [38]. From a secondary care perspective, barriers to greater integration are less those of training, but more of a lack of understanding of the culture of primary care, defensive attitudes and a lack of certainty over roles and responsibilities [39]. Poor communication across the interface is also an important barrier to integrated working. There appear to particular issues created by poor communication between psychiatrists and General Practitioners about non attendance by follow-up patients, who are often more unwell and harder to engage than new patients [40]. General Practitioners have also reported that they don't know the mental health consultant well enough to telephone them for advice and very few Community Mental Health Teams had a clear strategy for communication with primary care [41].

Conclusion

This paper has suggested that while the central thrust of a raft of recent Government policies in England has been towards integration of different parts of the health care system, policy waterfalls and implementation failures, the adoption of ideas before they have been thoroughly tried and tested, a lack of clarity over roles and responsibilities and poor communication have led to an integration rhetoric/reality gap in practice.

Whilst the paper has focussed on the English context, similar barriers to integration are being experienced in other health care systems and the arguments rehearsed here are applicable to many other national settings [1, 2]. Whilst policy may provide leverage for organisational restructure and reform, it does not necessarily provide the essential ingredients for professional collaboration. Relatively immature organisations have had to respond to a series of policy initiatives where there is often limited management expertise or organisational memory. Surveys have suggested problems with management capacity and expertise in commissioning services including mental health [42]. Some Primary Care Trusts and Mental Health Trusts have also inherited debts from the old Health Authorities making it more difficult to plan and provide new services. Inefficient interagency collaboration particularly where different parts of the system have different ideologies and priorities, inadequate mechanisms for enabling the shift of finance from hospitals to community care have also created problems.

Despite the increasing attention given to mental health policy in England, tensions remain between the planning and development of well-informed policy, underpinned by consistent and robust frameworks and the actual delivery and implementation of such policies, particularly in mental health. This paper has highlighted some of the social and political challenges involved in the implementation of mental health policy in England. These issues are by no means unique to the English situation and reflect experiences throughout Europe in implementing mental health policy.

There are no easy solutions. To facilitate integrated working, increased attention needs to be focussed on overcoming inter-organisational divides and inter-professional differences with the aim of fostering and maintaining commitment and enthusiasm for joint working. Knowledge sharing, respect for the autonomy of the different groups involved, the surrender of professional territory where necessary are key to the development and the effective sharing of values and goals [43, 44]. These can be encouraged by inter-professional education which enables practitioners to learn about each other's settings and strengths and encourage a culture of collaboration and mutual respect. Above all, however, a ‘policy amnesty’ to enable time and space for Primary Care Trusts, locality commissioning groups in primary care and Mental Health Trusts to catch up and rationalise their strategies is required to reduce the ‘push-me pull-you’ policy paradox of integrated mental health care.

Contributor Information

Dr Elizabeth England, Department of Primary Care, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, England, UK.

Dr Helen Lester, Department of Primary Care, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, England, UK.

Reviewers

Peter F M Verhaak, PhD, Research coordinator for mental health services research at the NIVEL, Netherlands institute for health services research, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Nick Goodwin, Dr, Senior Lecturer in Health Services Delivery and Organizational Research, Health Services Research Unit, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

Susan Gregory, Dr, Psychiatrist, Scientific Associate, Department of Health Economics, National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece.

References

- 1.Fleury MJ, Mercier C. Integrated local networks as a model for organizing mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2002;30(1):55–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1021227600823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horner D, Asher K. General practitioners and mental health staff sharing patient care: working model. Australasian Psychiatry. 2005;13(2):176–80. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2005.02184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey B, Levin E, Illife S, Kharicha K. Integrating health and social care: implications for joint and community care outcomes for older people. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(1):22–34. doi: 10.1080/1356182040021734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman G, Weaver T, Low J, de Jonge E. Promoting continuity of care for people with severe mental illness whose needs span primary, secondary and social care. A report for the NCCSDP. London: SDO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasby J, Lester HE, England E, Clarke M. Cases for change in mental health. Colchester: National Institute for Mental Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O'Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households 2000. London: TSO; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird L. The fundamental facts: all the latest facts and figures on mental illness. London: Mental Health Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 2001. Setting the standard: the new agenda for primary care organisations commissioning mental health services. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins R, Ustun T, Bedhiran E. Chichester: Wiley; 1998. Preventing mental illness: mental health promotion in primary care. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications – a discussion paper. [cited 2004 12 30];International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2002 Nov;14:2. doi: 10.5334/ijic.67. Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes RAW. London: Macmillan; 2000. Transforming British Government. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blount A. London: Norton and Co; 2000. Integrated primary care: the future of medical and mental health collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Co-ordinating primary care with community mental health services. In: Tansella M, Thornicroft G, editors. Common mental health disorders in primary care. London: Routledgel; 1999. pp. 222–5. p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preston C, Cheater F, Baker R, Hearnshaw H. Left in limbo: patients' views on care across the primary/secondary interface. Quality in Health Care. 1999;8:16–21. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ODPM. London: 2004. Mental health and social exclusion. Social exclusion unit report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 2004. Taking your partners: using opportunities for inter-agency partnership in mental health. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritchie Report. London: HMSO; 1994. Report of the inquiry into the care and treatment of Christopher Clunis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giddens A. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1998. The third way. A renewal of social democracy. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health. London: The Stationary Office; 1997. The new NHS: modern, dependable. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2001. Shifting the balance of power within the NHS: securing delivery. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2002. Shifting the balance of power within the NHS: the next steps. [Google Scholar]

- 22.BMA/NHS confederation. London: BMA/NHS confederation; 2003. Investing in general practice: the new general medical services contract. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 2004. Practice based commissioning in the NHS: the implications for mental health. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2004. The NHS improvement plan: putting people at the heart of public services. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig N, McGregor S, Drummond N, Fischbacher M, Illiffe S. Report to the NHS Executive North Thames. Department of Public Health, Glasgow University; 2002. The primary care led NHS 1: shifts in resources to primary care for three clinical conditions – an empirical study. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kingdon D. Mental Health Services: results of a survey in English district plans. Psychiatric Bulletin. 1989;13:77–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein LI, Test MA. An alternative to mental hospital treatment. I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:392–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoult J. Community care of the acutely mentally ill. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149:137–44. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 1999. National Service Framework for Mental Health: modern standards and service models. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health. The NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2002. Mental health policy implementation guidance: community mental health teams. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns T. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. Community mental health teams: a guide to current practices. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelosi A, Birchwood M. Is early intervention of psychosis a waste of valuable resources? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003 Mar;182:196–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.3.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg D, Huxley P. London: Routledge; 1992. Common mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lester HE, Glasby J, Tylee A. Integrated primary care mental health: threat or opportunity in the new NHS. British Journal of General Practice. 2004;54:285–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2003. Guidelines for the appointment of general practitioners with special interests in the delivery of clinical services: Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 37.NICE, Schizophrenia. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists and the British Psychological Society; 2003. Full national clinical guidelines on core interventions in primary and secondary care. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mental After Care Association. London: MACA; 1999. First national GP survey of mental health in primary care. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolan P, Dunn L, Badger F. Getting to know you. Nursing Times. 1998;94(39):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, Lloyd M. Non-attendance at psychiatric outpatient clinics: communication and implications for primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 1999;49:880–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bindman J, Johnson S, Wright S, Szmukler G, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Integration between primary and secondary services in the care of the severely mentally ill: patients' and general practitioners' views. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;171:169–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lester HE, Sorohan H. Barriers and organisational development needs for effective PCT commissioning of mental health services. Primary Care Mental Health. 2003;1:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeth D, Reeves S. Evaluation of an interprofessional training ward: pilot phase. In: Glen S, editor. Multi-professional learning for nurses: Breaking the boundaries. Hampshire: Palgrave; 2002. pp. 116–38. p. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammick M, Barr H, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S. Systematic reviews of inter-professional education: results and work in progress. Journal of Inter-professional Care. 2002;16:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]