Summary

We investigated the epidemiology of intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka by prospectively recording 2189 admissions to two secondary hospitals. Many patients were young (median age 25yrs), male (57%), and used pesticides (49%). 198 died, 156 men (case fatality 12.4%) and 42 women (4.5%). 52% of female deaths were in those <25yrs; male deaths were spread more evenly across age groups. Oleander and paraquat caused 74% of deaths in people <25yrs; thereafter organophosphorus pesticides caused many deaths. Although the age-pattern of self-poisoning was similar to industrialised countries, case-fatality was >15 times higher and the pattern of fatal self-poisoning quite different.

Intentional self-poisoning is a common clinical problem worldwide (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2002). In industrialised countries, it predominantly occurs in young people impulsively responding to stressful events with little desire to die. Deaths are rare since the medicines commonly taken are of low toxicity or easily treated. The situation is different in the developing world where pesticides are the most popular means of self-poisoning (Eddleston, 2000; Gunnell & Eddleston, 2003) and cause an estimated 300,000 deaths each year in the Asia-Pacific region (Eddleston & Phillips, 2004). Relatively little is known about the age and gender patterns of fatal and non-fatal self-poisoning in such regions. This study aimed to identify the patterns and poisons used in an agricultural area of Sri Lanka with the expectation that such knowledge will direct future campaigns to prevent self-harm.

Methods

A prospective study was established in the two secondary hospitals (Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa) of the North Central Province of Sri Lanka in 2002. This province is an agricultural region with 1.1 million people; 55% are less than 25yrs. Ethics approval was obtained from Oxford and Colombo. Poisoned patients are first admitted to rural hospitals; around 50% are then transferred to the secondary hospitals according to severity and facilities available (Eddleston, unpublished). From 31/03/02 until 15/03/03, all patients with self-poisoning were seen on admission by study doctors and data entered into a database. The poison was identified from the history, bottles, transfer letter, and/or clinical toxidrome. Blood samples were taken from 70% of patients; retrospective analysis showed that the poison was correctly identified in >80% of cases.

We used logistic regression models to investigate the effects of age, gender and poison type on mortality. As there were no deaths amongst those taking acids, hydrocarbons, or alkalis, patients taking these poisons (n=77) were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Altogether 2189 patients with acute self-poisoning were identified over the study period. 68 patients had occupational or unintentional exposure and are not analysed here.

Males accounted for more cases (n=1257, 57%) than females. The age distribution of cases was: <15: 3.5%; 15–24: 44.5%; 25–34: 25.1%; 35–44: 14.8% and 45+: 12.1%. The overall median was 25 years (inter-quartile range (IQR): 19 to 35); female cases were younger than males (median age 21, IQR 17–29 vs. 29, IQR 22–40). The 5-year age band with the highest number of cases was 15–19 in women and 20–25 in men.

The commonest poisons ingested were pesticides (49%), particularly by men (males 59%, females 35%), and oleander seeds (34%; males 31%, females 38%). Oleander was the commonest poison used by females and males under the age of 20. From age 20, pesticides became more common in both sexes. Medicines and hydrocarbons (commonly kerosene) were more often taken by women than men (18% vs. 3%, and 6% vs 2%, respectively).

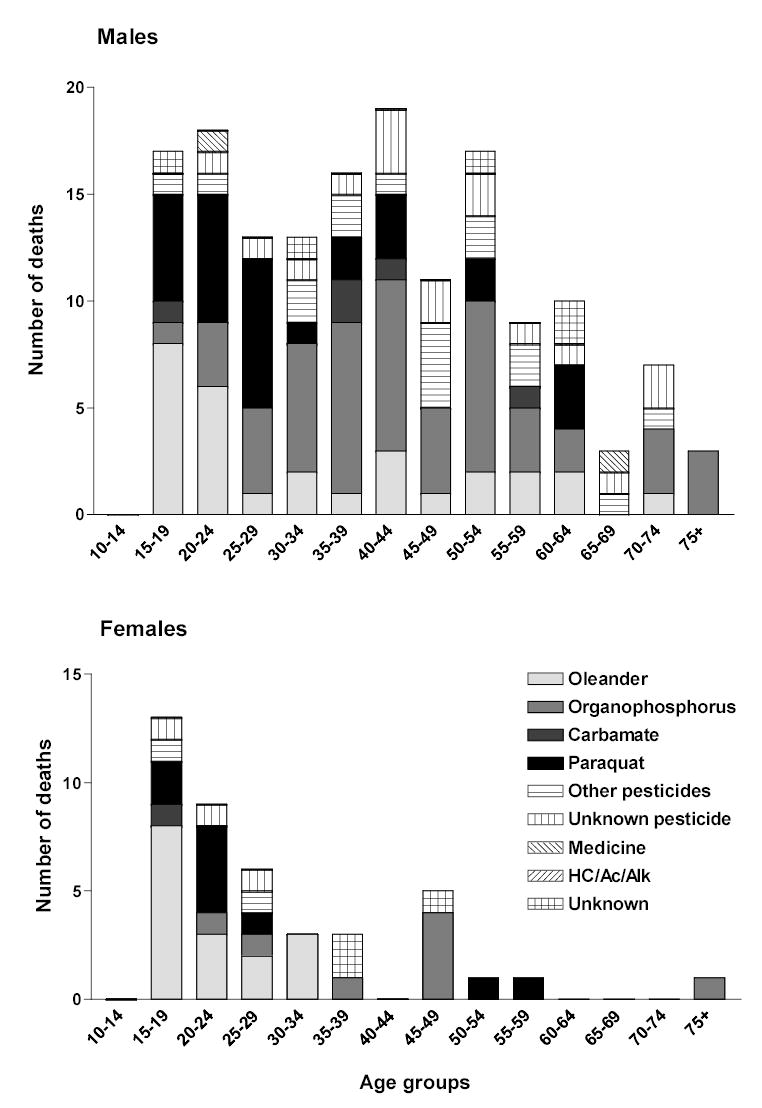

198 patients died (case fatality ratio [CFR] 9.0%). CFR was higher in males (12.4%) than females (4.5%). 52% of female deaths occurred in women under 25; male deaths were spread more evenly with only 22% of deaths occurring in men under 25yrs (Figure 1). CFR increased with age. In a logistic regression model controlling for sex and type of poison taken, the risk of death increased by 62% (95%CI 45–81%) per 10-year increase in age and was 52% (4% to 124%) higher in males than females.

Figure 1.

Poisons used for fatal self-poisoning by A. males and B. females according to age.

Oleander and paraquat were the most important means of fatal self-poisoning in both sexes under 25yrs (fig.1) accounting for 74% of deaths. Pesticides in general, and organophosphates in particular, became more important thereafter, responsible for at least 80% (organophosphates 40%) of deaths over the age of 25.

After controlling for age and sex in logistic regression models and using medicine as the reference category, the OR for death amongst patients poisoned by pesticides other than paraquat was 8.7 (95%CI 2.1–36.2); by paraquat 102.0 (22.8–456.4); and by oleander 7.2 (1.7–30.5). The OR for death with an unknown poison was 8.3 (1.7–40.9).

Discussion

The age-specific pattern of self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka is similar to that in industrialised countries – most cases occur in young people and the incidence peaks around 15–25, five years earlier in females than males, and then falls steadily with increasing age (see figure 1 of Gunnell & Eddleston, 2003, for comparison).

There are, however, a number of important differences. Male patients outnumbered women by 1.35:1 – the opposite to most other regions(Schmidtke et al, 1996; Hawton & van Heeringen, 2002). The CFR for self-poisoning patients admitted to Sri Lankan secondary hospitals (9%) is much higher than in industrialised countries (eg. 0.5% in the UK (Gunnell et al, 2004)). A significant number of deaths (52% of female deaths, 11% of all deaths) occur in young women <25yrs. A similar pattern of fatal self-poisoning in young women is seen in rural areas of China and India (Phillips et al, 2002; Joseph et al, 2003).

This study was secondary hospital based and therefore not directly comparable with population-based data. Patterns of transfer from rural hospitals, in particular an increased tendency for transfer of men, would have biased the pattern of admission. A preliminary study has so far found no gender bias for transfers, nor evidence of more women dying before transfer to the secondary hospitals. The CFR would have been lower if all patients admitted to rural hospitals were transferred, but still several fold higher than in industrialised countries.

The substances used in fatal poisoning varied with age and with gender. Yellow oleander was most common in people under 20yrs. Paraquat was important in young people; after 30yrs other pesticides (particularly OPs and non-paraquat herbicides) became more important. All are significantly more difficult to treat than the medicines that are commonly used in the West.

This study supports the view that OP pesticides are important causes of fatal self-poisoning in south Asia (Khan, 2002; Roberts et al, 2003). Paraquat and oleander may be more important in women and young people since they are highly toxic and even small amounts can kill.

The CFR rose steeply with age in men and women. This may reflect a greater level of intent in older patients, a greater use of pesticides for self-poisoning, or a problem of co-morbidity.

Overall, the higher case fatality is predominantly due to the availability of highly toxic poisons and the difficulty of medical management. Restriction of access to highly toxic pesticides, plus improved medical therapy and antidote availability, could rapidly reduce the number of self-poisoning deaths in the rural developing world.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ox-Col study team and the hospitals’ medical and nursing staff for their help; and Nick Bateman and Keith Hawton for critical review. ME is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow funded by GR063560MA.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None. Funding detailed in acknowledgements.

References

- 1.Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJMed. 2000;93:715–731. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.11.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eddleston M, Phillips MR. Self poisoning with pesticides. BMJ. 2004;328:42–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7430.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries. IntJEpidemiol. 2003;32:902–909. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunnell D, Ho DD, Murray V. Medical management of deliberate drug overdose - a neglected area for suicide prevention? Emergency MedJ. 2004;21:35–38. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton, K., van Heeringen, K. E. (2002) The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. John Wiley & Sons.

- 6.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies,1994-9. BMJ. 2003;326:1121–1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MM. Suicide on the Indian subcontinent. Crisis. 2002;23:104–107. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.23.3.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, et al. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360:1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts DM, Karunarathna A, Buckley NA, et al. Influence of pesticide regulation on acute poisoning deaths in Sri Lanka. BullWorld Health Organ. 2003;81:789–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, de Leo D, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]