Abstract

Unstated and unacknowledged bias has a profound impact on the nature and implementation of integrative education models. Integrative education is the process of training conventional biomedical and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in each tradition such that patient care may be effectively coordinated. A bilateral education model ensures that students in each tradition are cross-taught by experts from the ‘other’ tradition, imparting knowledge and values in unison. Acculturation is foundational to bilateral integrative medical education and practice. Principles are discussed for an open-minded bilateral educational model that can result in a new generation of integrative medicine teachers.

Keywords: acculturation, bilateral education, integrative medicine, TCM

Introduction

The widespread use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) among patients of biomedical practitioners has been widely documented (1–3). It might be implicitly accepted (which may explain why it is less commonly acknowledged) that patients of CAM practitioners are almost always patients of conventional physicians, as well (4). Patient care should be coordinated when multiple providers are involved. However, coordination of care rarely occurs when the providers are from two distinct traditions, i.e. conventional biomedicine and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Nomenclature for referring to medical disciplines is a subject in its own right (5).

Integrative education is, in this example, the process of training conventional biomedical and TCM practitioners in each tradition such that patient care may be effectively coordinated. When practitioners from these distinct and prevalent medical systems are familiar with the diagnosis and treatment plan of the other, the patient can only benefit. A bilateral educational model ensures that students in each tradition are taught by experts from each tradition.

Finding Balance by Addressing Bias

It should be obvious that the process of integrative education, e.g. placing practitioners from each tradition in the clinics and the classrooms, is not balanced. This imbalance is evident in discussion and implementation of how to integrate academically. Stating the obvious in the case of integrative medicine is important, especially when the two disciplines differ so fundamentally in their approach to patient care.

Unstated bias shades most integrative activities from research to instructional models. Educational models in the United States that promote the integration of TCM and conventional medicine are far from standard and decidedly one-sided.

The conventional medical model places a very high priority on understanding the biological mechanisms of action that underlie acupuncture as a prerequisite of practice. It follows logically that TCM practitioners should know more about the biomedical approach. In our pain management professional acupuncture and Oriental medicine doctorate program there is a strong belief that learning more orthopedics only strengthens the ability of the TCM practitioner to practice more effectively, especially when integrating with conventional medical providers. However, if understanding the mechanism of action for serotonin uptake inhibitors is not necessary for diagnosing and treating depression in conventional medical practice it certainly should not be in TCM. The process of integration is more than teaching the biomedical approach to TCM students or surveying TCM for medical students.

Surveys of integrative education tend to focus on conventional medical schools, suggesting TCM schools are only involved at the point of service delivery. A recent survey of nine leading academic medical centers in Canada revealed a variety of models for exposing medical students to CAM. A common model included recruiting ‘cross-trained’ CAM providers to lecture or otherwise interact on campus. One school employed an ‘elective exchange’ model wherein medical students met with TCM students to discuss approaches to patient care (6). A survey of 19 US osteopathic medical schools showed that all but one included CAM instruction. Teaching, which originated across different clinical departments, did not exceed 20 h and typically occurred in the first two years. Surprisingly, 18 of the 25 identified instructors were reported as CAM providers (7). A CAM instruction survey within US medical schools was completed by 117 (94%) schools (8). Seventy-five schools (64% of 117) reported offering CAM instruction, mostly as electives (84 of 123 courses, 68%), for the most part through Family Medicine and Medicine/Internal Medicine departments (52 or 42%). The 1999–2000 annual survey of medical education programs found similar results (9).

Patient Care is the Question and the Answer

Education that leads to integration will be successful when more instructional models strive to represent how each tradition approaches the patient. Integrative education that balances both perspectives on patient care must take place and should no longer be challenged as a training goal. Nevertheless, harsh challenges can be found in the academic literature. A recent editorial in a Croatian medical journal stated that scientific proof of CAM effectiveness based on mechanisms of action are not to be found concluding that CAM is a ‘plain fraud’ (10). A letter to the editor (11) responded to an article suggesting that increased frequency of CAM use by patients justifies inclusion of CAM instruction in medical school curricula (12). The writer concluded that to do so would ‘drop the standards for medical curriculum to below those for medical practice’ effectively ‘dumbing down’ medical education.

While integrative education may remain somewhat controversial within US academic medical centers, many conventional medicine educators and students recognize that, in the least, physicians must be able to communicate with their patients about the CAM treatments patients seek out on their own (13–15).

The challenges academic medicine faces developing an integrative curriculum typically focus on introducing CAM practices as factoids instead of complicated systems of knowledge. The CAM practices commonly featured are herbal medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, complementary nutrition, mind–body therapies and massage (13,16,17). Instruction in CAM methods that might lead to change in physician practice is rare. Generally, the emphasis is on the ‘importance of improving physician–patient relationship and enriching the [medical provider] both professionally and personally’ (13).

It is plain that TCM practitioners must know how to interact with conventional providers and the medical system in general. This simple recognition is another case of stating the obvious when it comes to integration models. We found only one reference that described what we would consider a bilateral model, e.g. recognizing the ‘importance of educating CAM practitioners to interact with conventional physicians, the public, and policy makers …’ (18).

Acculturation: The Obvious Path

We argue the first step in establishing integrative education models is not a matter of content but one of acculturation versus assimilation. Preservation of TCM values and knowledge as TCM is integrated with conventional medicine is preferred to changing TCM so that it more closely resembles or even becomes a subset of conventional medicine.

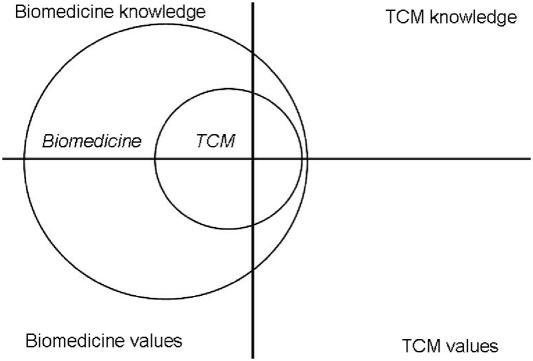

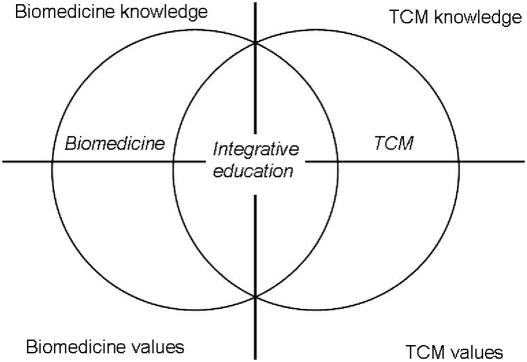

In assimilation, the values and knowledge of TCM are subordinated to those of conventional medicine, the outcome of which leaves the techniques without a theoretical framework (Figs 1 and 2). Acculturation requires each system to inform the other while maintaining intrinsic values and knowledge.

Figure 1.

Assimilation.

Figure 2.

Acculturation.

The potential benefit of a medical model that integrates Eastern and Western medicines is documented in a 2004 article (19). The language is worth noting for its optimism and respect in a balanced discussion of how TCM and biomedicine converge to reveal new understanding and treatment approaches for functional somatic syndromes: ‘… the convergence of these biomedical models with the ancient healing tradition of TCM may provide novel perspectives in understanding these challenging and elusive disorders’.

Sensitivity to the dominance of conventional medicine is certainly acute among TCM providers. The primacy of conventional medicine, the secondary role of other traditional medicines and the barriers this simple dyad presents to providers and patients is evident, it has been argued, in the use of terms like ‘alternative’ and ‘complementary’ (5).

Paradigm Shift in Scientific Theory Applies to Biomedicine

Biomedical reductionist versus Chinese wholistic philosophies have been scrutinized and questioned with tremendous implications for mutual comprehension and East–West integration (20). The atomistic approach that has resulted in the identification of bacteria and viruses leading to effective treatment methods has no complement in the TCM approach to health where the person and the disease are inseparable and person-focused treatment logically overcomes disease by restoring individual balance. The difference is akin to the shift in modern physics, whereby quantum, chaos and complexity theories have overtaken atomistic linear models of 17th and 18th century physics for most phenomena (21). An approach that dominated scientific thought for 500 years has been supplanted because it no longer provides direction for understanding phenomena empirically observed but scientifically unexplainable. This simplified example illustrates the open-mindedness that must accompany integration of TCM and conventional biomedicine.

To paraphrase Pritzker (21) the intuitive practices that are highly valued in TCM are often interpreted as scientifically insufficient in conventional medicine. This judgment may be inappropriate given that the familiar Western concepts of quantification, objectivity and scientific rigor are without complement when compared with the Eastern canons of intuition, tendency and dynamism in comprehending health. It seems intuitively true that TCM is intrinsically more integrative, providing a more effective model for integrating Eastern and Western medical cultures. Conventional medicine is based on the process of gathering evidence to eliminate competing diagnoses in order to arrive at the specific correct diagnosis. TCM is based on gathering information leading to recognition of a familiar pattern for which a treatment plan that addresses the entire person is recommended.

Suspend Disbelief

Conventional medical hegemony in terms of knowledge and values must be recognized and suspended when attempting to understand TCM. Opportunities for conventional medicine to discount TCM are ubiquitous. The concept of qi is a case in point. Qi is a fundamental Chinese concept with at least 2000 years of history in Chinese medicine. It is a word used by billions of Chinese people everyday, yet, for the great majority of biomedical scientists, it is something unproven, even fantastic.

It might be better for conventional medicine to approach TCM in the same manner as the therapeutic effects of prayer or positive guided imagery. Suspension of disbelief, a foundational concept in cultural anthropology, must be the first skill applied by medical students when learning the principles of TCM. Mutuality within the instructional model is key to learning. TCM instruction for medical students and faculty must be delivered by TCM instructors. Likewise, conventional medical instruction for TCM students must be delivered by Western medical instructors.

Thoughtful commentators within conventional medicine have suggested that introducing CAM in medical school is ‘invaluable’, forcing ‘thinking outside the box’. Among the merits are the ‘opportunity to look at conventional medicine from a different perspective … the development of critical appraisal’, and the acquisition of ‘vital information about the practice of CAM’ (22).

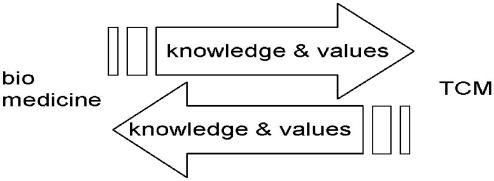

In a bilateral educational model, knowledge and values flow in both directions, and are informed by each system's theoretical framework. TCM content is taught by TCM experts and biomedical content is taught by biomedical experts (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Bilateral education.

Integrative Teachers

The Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine Implementation Guide for Curriculum in Integrative Medicine (23) lists 11 modules totaling ∼100 h. While the guide is truly commendable and represents a step towards integration it is fundamentally assimilative. Only three of the modules call for a CAM provider paired with academic medical faculty. These include a 4 week long evidence-based integrative medicine course. Introduction to herbal medicine is not instructor-integrated. Two recent physician surveys (24,25) found ‘deficits in knowledge’ and ‘substantial room for improvement in knowledge, attitudes and clinical practice’ regarding herbs. At least one study (26) reported that 78% of CAM courses taught in medical schools were taught by ‘CAM practitioners or prescribers of CAM therapies’. If it is the case that the preponderance of ‘CAM practitioners or prescribers of CAM therapies’ teaching medical school CAM courses are MDs, then it is likely that CAM knowledge and values are being lost in translation.

The approach we have taken in our acupuncture and Oriental medicine doctorate program is to pair conventional TCM with conventional medicine teachers. We believe, over time, synergy will yield something greater than the sum of the individual systems: teachers of integrative medicine informed by and informing both traditions. We describe the implementation of our bilateral approach in a subsequent report.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, Van Rompay ML, Walters EE, Wilkey SA, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MM. CAM practitioners and “regular” doctors: is integration possible? Med J Aust. 2004;180:645–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiseman N. Designations of medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:327–9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Walters K, Heather B. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic medical centers: experience and perceptions of nine leading centers in North America. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:78. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxon DW, Tunnicliff G, Brokaw JJ, Raess BU. Status of complementary and alternative medicine in the osteopathic medical school curriculum. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104:121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wetzel MS, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ. Courses involving complementary and alternative medicine at US medical schools. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:784–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.9.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barzansky B, Jonas HS, Etzel SI. Educational programs in US medical schools, 1999–2000. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:1114–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.9.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marusic M. “Complementary and alternative” medicine—a measure of crisis in academic medicine. Croat Med J. 2004;45:684–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff S. Letter to the editor: complementary and alternative medical education. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetzel MS, Kaptchuck TJ, Haramati A, Eisenberg DM. Complementary and alternative therapies: Implications for medical education. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:191–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frenkel M, Ben-Arye E, Hermoni D. An approach to educating family practice residents and family physicians about complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical School Objectives Project. Report I: Learning Objectives for Medical Student Education-Guidelines for Medical Schools. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Schools; 1998. p. 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Educational Development for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (EDCAM): CAM and Medical Education Report. Available at: http://www.amsa.org/humed/cam/mededreport.cfm.

- 16.Kemper KJ, Highfield ES, McLellan M, Ott MJ, Dvorkin L, Whelan JS. Pediatric faculty development in integrative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8:70–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemper KJ, Vincent EC, Scardapane JN. Teaching an integrated approach to complementary, alternative, and mainstream therapies for children: a curriculum evaluation. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:261–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills EJ, Hollyer T, Guyatt G, Ross CP, Saranchuk R, Wilson K. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Working Group. Teaching evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: a learning structure for clinical decision changes. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:207–14. doi: 10.1089/107555302317371514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan S, Tillisch K, Mayer E. Functional somatic syndromes: emerging biomedical models and traditional chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:35–40. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tada T. Toward the philosophy of CAM: super-system and epimedical sciences. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:5–8. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pritzker S. From the simple to the complex: what is complexity theory, and how does it relate to Chinese medicine? Clin Acupunct Orient Med. 2002;3:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen D, Lewith GT. Teaching integrated care: CAM familiarisation courses. Med J Aust. 2004;181:276–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kligler B, Maizes V, Schachter S, Park CM, Gaudet T, Benn R, et al. Education Working Group, Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine. Core competencies in integrative medicine for medical school curricula: a proposal. Acad Med. 2004;79:521–31. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolf AD, Gardiner P, Whelan J, Alpert HR, Dvorkin L. Views of pediatric health care providers on the use of herbs and dietary supplements in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44:579–87. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemper KJ, Amata-Kynvi A, Dvorkin L, Whelan JS, Woolf A, Samuels RC, et al. Herbs and other dietary supplements: healthcare professionals' knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:42–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brokaw JJ, Tunnicliff G, Raess BU, Saxon DW. The teaching of complementary and alternative medicine in U.S. medical schools: a survey of course directors. Acad Med. 2002;77:876–81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]