Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the combination of lymphodepleting chemotherapy followed by the adoptive transfer of autologous tumor reactive lymphocytes for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma.

Patients and Methods

Thirty-five patients with metastatic melanoma, all but one with disease refractory to treatment with high-dose interleukin (IL)-2 and many with progressive disease after chemotherapy, underwent lymphodepleting conditioning with two days of cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg) followed by five days of fludarabine (25 mg/m2). On the day following the final dose of fludarabine, all patients received cell infusion with autologous tumor-reactive, rapidly expanded tumor infiltrating lymphocyte cultures and high-dose IL-2 therapy.

Results

Eighteen (51%) of 35 treated patients experienced objective clinical responses including three ongoing complete responses and 15 partial responses with a mean duration of 11.5 ± 2.2 months. Sites of regression included metastases to lung, liver, lymph nodes, brain, and cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Toxicities of treatment included the expected hematologic toxicities of chemotherapy including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia, the transient toxicities of high-dose IL-2 therapy, two patients who developed Pneumocystis pneumonia and one patient who developed an Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphoproliferation.

Conclusion

Lymphodepleting chemotherapy followed by the transfer of highly avid antitumor lymphocytes can mediate significant tumor regression in heavily pretreated patients with IL-2 refractory metastatic melanoma.

INTRODUCTION

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy is based on the ex vivo selection of tumor-reactive lymphocytes, and their activation and numerical expansion before re-infusion to the autologous tumor-bearing host.1 Murine models of ACT have established the ability of this approach to mediate the regression of established cancers and have provided important principles to guide human studies.2-4In murine models, prior host immunosuppression can dramatically improve the antitumor effects of ACT therapy.5,6 Additional improvements can be achieved by the systemic administration of interleukin (IL)-2 or other cytokines to support the transferred cells, and concurrent immunization with inflammatory formulations of the tumor antigen recognized by the transferred cells.7,8

In the National Cancer Institute (NCI; Bethesda, MD) Surgery Branch, we have developed improved methods for the generation of human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) with antitumor activity9,10 and have administered these TILs in combination with prior immunosuppression and the administration of IL-2.11 We previously reported that six (47%) of 13 patients with IL-2 refractory metastatic melanoma treated with this combination experienced an objective partial response. Two of the responding patients exhibited a transient lymphocytosis composed primarily of the transferred, tumor-reactive TIL cells. These two patients further demonstrated a clonal repopulation of their immune systems, with more than 70% of their peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) consisting of a single tumor reactive clone for over four months after treatment.

In the current study, we extend these results to report on the treatment of a total of 35 patients with refractory metastatic melanoma using selected, rapidly expanded TIL cultures and high-dose IL-2 therapy after nonmyeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Eighteen (51%) of the 35 treated patients demonstrated an objective response to treatment, and eight others demonstrated a mixed or minor response. Some patients also exhibited symptoms of autoimmune melanocyte destruction including vitiligo or uveitis. The results and analysis reported here help elucidate many of the principles required for the immune-mediated destruction of established cancers.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Treatments and Clinical Assessment

Patients older than 18 years with stage IV melanoma who were negative for hepatitis B and C and HIV infection and had a good performance status and a life expectancy of at least 3 months were eligible for treatment on this protocol. All patients signed an institutional review board-approved consent and had melanoma that was histologically confirmed by pathologists at the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). All patients had assessable disease (measurable disease on computed tomography scan or by physical exam) refractory to standard treatments including high-dose IL-2 therapy (except patient 31, who did not receive IL-2 before entry into this protocol). Five (14.7%) of the 34 patients who received high-dose IL-2 initially responded to IL-2 therapy alone, but then exhibited progressive disease and were enrolled on this protocol. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized stem cells were obtained by leukapheresis from all patients and cryopreserved before initiation of chemotherapy in the event that patients did not reconstitute their hematopoetic system. Patients received nonmyeloablative lymphodepleting chemotherapy as previously described12,13 consisting of 2 days of cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg) followed by 5 days of fludarabine (25 mg/m2). On the day following the final dose of fludarabine, patients received cell infusion with tumor-reactive lymphocytes and high-dose IL-2 therapy consisting of 720,000 IU/kg intravenously every 8 hours to tolerance as previously described.14,15 After enrollment of 15 patients, the protocol was amended through the institutional review process so that all subsequent patients who had MART-1-specific16 or gp100-specific17 TIL received vaccination with 1 mg MART-1:26-35(27L) or gp100:209-217(210M) peptide in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) injected subcutaneously.

Patients’ hematologic parameters were monitored daily by obtaining complete and differential blood counts, and by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral mononuclear cells. Patient response was assessed using standard radiographic studies and physical examination at four weeks following cell administration and at regular intervals thereafter. A complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all clinical evidence of disease. A partial response (PR) was defined as a 50% or greater decrease in the sum of the products of perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions for at least one month with no increase in any lesion and no new lesions. Appearance of any new lesion or greater than 25% increase in any lesion following a PR or CR was considered a relapse. A CR or PR was considered to be an objective response, and duration was measured from the initiation of treatment to the time of relapse. Patients with mixed or minor responses or progressive disease were considered nonresponders.

Patient Materials and Cell Lines

TIL cultures for treatment were generated as previously described.9 This clinical trial was not designed to predict response rates on an intent-to-treat basis. Our prior analysis of sequential melanoma biopsies from HLA-A2+ patients demonstrated that tumor specific activity was detectable in TILs from 29 (81%) of the 36 patients screened.9 In brief, the method for TIL generation involved the initiation of multiple independent cultures in 24 well plates, which were maintained at 0.8-1.5 × 106 cells/mL. When sufficient TILs were available, each culture was tested by cytokine-release assay for antigen specificity and tumor reactivity. Active TIL cultures were expanded to treatment levels using a rapid expansion protocol (REP) as previously described18,19 with OKT3(anti-CD3) antibody (Ortho Biotech, Bridgewater, NJ) and IL-2 in the presence of irradiated, allogeneic peripheral-blood mononuclear cells from at least three different donors. The rapidly expanded cultures were typically maintained for 13 to 14 days before patient infusion, and were infused into the patient by intravenous administration over 30 minutes.

Immunologic Assays

TIL activity and phenotype were determined by analysis of cytokine secretion, flourescence activated cell scanning (FACS), and immunocytochemistry as previously described.9,20,21

Statistical Analysis

Significance of variation between groups was evaluated using a two-tailed Student t test assuming equal or unequal variance with P ≤ .05 considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Thirty-five patients with assessable metastatic melanoma who had TIL cultures that recognized autologous or HLA-matched tumor cells were eligible for treatment on this protocol. The demographic characteristics of this patient population are shown in Table 1. All but two patients (patients 34 and 35) were HLA-A*0201+. All patients had progressive disease after receiving multiple prior therapies before treatment on this protocol, including surgery and (except patient 31) high-dose IL-2 therapy, and 18 of the patients had progressive disease after receiving chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Characteristics | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 35 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 21 | 60 |

| Female | 14 | 40 |

| Age, years | ||

| 11-20 | 1 | 3 |

| 21-30 | 3 | 9 |

| 31-40 | 6 | 17 |

| 41-50 | 13 | 37 |

| 51-60 | 10 | 29 |

| 61-70 | 2 | 6 |

| Performance status* | ||

| 0 | 29 | 83 |

| 1 | 6 | 17 |

| Prior treatments | ||

| Surgery | 35 | 100 |

| Chemotherapy | 18 | 51 |

| Radiotherapy | 11 | 31 |

| Hormonal | 1 | 3 |

| Immunotherapy | 35 | 100 |

| Any,≥2 | 35 | 100 |

| Any,≥3 | 22 | 63 |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale.

Each patient had one or more metastatic lesions resected for the generation of lymphocyte cultures and autologous tumor cell targets.9 The activity and specificity of three representative TIL cultures used for treatment are shown in Table 2.All TIL cultures that recognized allogeneic HLA-A2-matched melanoma cells were screened for recognition of MART-1:27-35 and gp100:209-217 peptides.

Table 2.

Antigen Specificity and Activity of Representative TIL Cultures Infused for Patient Treatment (IFNγ, pg/mL)

| T2 With Peptide* |

Mel(A2-)† |

Mel(A2+) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | MART | gp100 | 888 Mel | 938 Mel | 526 Mel | 624 Mel | Autol Mel‡ | Specificity | |

| Patient Rx TIL | |||||||||

| Patient 6 | ND | ND | ND | 144 | 136 | 241 | 260 | 5.980 | Autol |

| Patient 18 | 2,922 | 1,985 | 37,895 | 1,381 | 857 | 16,130 | 18,665 | 20,365 | gp100 |

| Patient 28 | 0 | 9,725 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,895 | 528 | 16,435 | MART-1 |

| Controls§ | |||||||||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | None |

| ML2D8 | 0 | 0 | 2,503 | 20 | 0 | 23,695 | 14,900 | 16,875 | gp100 |

| JB2F4 | 0 | 16,160 | 407 | 0 | 0 | 11,975 | 3,505 | 15,880 | MART-1 |

| AK 1700-3 | 114 | 125 | 127 | 81 | 53 | 61 | 82 | 56 | Autol |

NOTE. Significant cytokine release (indicated by boldfaced text) was defined as at least 100 pg/mL and twice background. Lymphocyte cultures used for patient treatment were typically assayed for specificity and activity 6 days after initiation of rapid expansion and 8 days prior to patient infusion. Values indicate IFNγ(pg/mL) secreted by lymphocytes (controls or Rx TIL cultures) stimulated in overnight coculture with the indicated antigen-presenting cells.

Abbreviations: Mel, melanoma tumor cell lines; none, no peptide; MART, MART-1:27-35; gp100, gp100:209-217; autol, autologous; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; ND, not done; ML2D8, HLA-A2-restricted and gp100:209-217-specific cloned T cell line; JB2F4, HLA-A2-restricted and MART-1:27-35-specific cloned T-cell line; AK 1700-3, a highly active but not rapidly expanded HLA-A2-restricted TIL line from patient 1 that recognized a unique melanoma antigen expressed by its autologous melanoma (not shown).

T2 cells were pulsed with 1μM of the indicated peptide and washed extensively before use as stimulator cells.

Mel(A2-), expressing HLA antigens other than HLA-A2. Mel(A2+), melanoma cell lines matched for HLA-A2.

Derived from the autol patient and matched at all HLA loci. TIL from patient 6 released 5,980 pg/mL IFNγ when stimulated with autol mel; TIL from patient 18 recognized autol mel with 20,365 pg/mL IFNγ ; and TIL from patient 28 recognized cognate melanoma cells with a release of 16,435 pg/mL IFN γ. The mel derived from patient 28 were used to stimulated the control effectors to obtain the values reported in the Autol Mel column.

The indicated control T-cell lines with known specificity were typically included in each assay to evaluate the stimulatory capacity of the antigen-presenting cells. The table is a compliation from independent assays, and values indicated for the control lines were obtained in the assay in which patient 28’s TILs were evaluated.

Clinical Results

Individual treatments varied based on the growth rates of cells and patient tolerance of IL-2 administration and are summarized in Table 3.A mean of 6.3 × 1010 cells was infused (range, 1.1 to 16.0 × 1010), comprising from one to four independently expanded TIL cultures per patient.

Table 3.

Treatment Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of cells (× 1010) | ||

| 1.0-3.0 | 10 | 29 |

| 3.1-6.0 | 10 | 29 |

| 6.1-9.0 | 4 | 11 |

| 9.1-12.0 | 7 | 20 |

| >12.1 | 4 | 11 |

| Antigens recognized | ||

| Unknown/autologous only | 9 | 26 |

| Gp100 only | 2 | 6 |

| MART-1 only | 12 | 34 |

| Autologous and gp100 | 2 | 6 |

| Autologous and MART-1 | 7 | 20 |

| Gp100 and MART-1 | 2 | 6 |

| Autologous, MART-1 and gp100 | 1 | 3 |

| CD8*, % | ||

| 0-20 | 2 | 6 |

| 21-40 | 4 | 11 |

| 41-60 | 3 | 9 |

| 61-80 | 5 | 14 |

| 81-100 | 21 | 60 |

| Fold expansion† | ||

| ≤500 | 6 | 17 |

| 501-1,000 | 8 | 23 |

| 1,001-1,500 | 7 | 20 |

| 1,501-2,000 | 10 | 29 |

| ≤2,001 | 4 | 11 |

| Absolute IFNγrelease (ng/mL)‡ | ||

| <1 | 4 | 11 |

| 1-4 | 13 | 37 |

| 5-9 | 6 | 17 |

| 10-15 | 5 | 14 |

| ≥16 | 7 | 20 |

| IL-2 doses administered | ||

| 4-6 | 8 | 23 |

| 7-9 | 14 | 40 |

| 10-12 | 11 | 31 |

| 13-15 | 2 | 6 |

Abbreviations: IFNγ, interferon-γ; IL-2, interleukin-2; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte.

Percentage of single positive CD8 cells is indicated. Most of the other cells were CD4single positive cells, with generally less than 5% of cells exhibiting a double-positive or double-negative phenotype.

Fold expansion during the rapid expansion phase is shown. For patients with more than one TIL culture in the final infusion product, the culture with the highest fold expansion is shown.

Highest IFNγsecretion for any administered TIL stimulated with allogeneic HLA-A2+or autologous tumor.

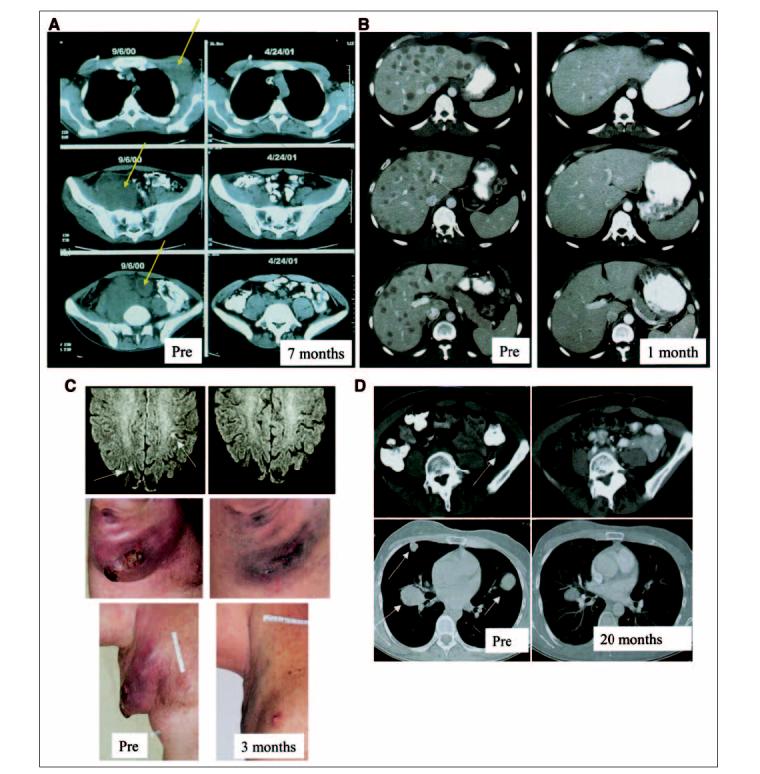

Eighteen (51%) of the 35 patients experienced objective clinical responses to treatment (three CRs and 15 PRs); their sites of tumor regression and duration of response are listed in Table 4.Eight other patients (23%) experienced mixed or minor responses to treatment. Regression of metastatic melanoma in diverse anatomic locations was seen, including bulky cutaneous and subcutaneous disease; widespread nodal disease in peripheral or central locations (Fig 1A); liver metastases (Fig 1B); multiple sites including brain and axillary disease (Fig 1C); lung and lymph nodes (Fig 1D); and lung and subcutaneous sites (Fig 1E).

Table 4.

Clinical Responses to Treatment

| Patient No.* | Sites of Disease | Response | Duration (months)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Axillary, mesenteric, and pelvic lymph nodes | PR | 29 |

| 2 | Subcutaneous and skin | PR | 8 |

| 4 | Iliac and inguinal lymph nodes, skin | PR | 2 |

| 6 | Intraperitoneal lymph nodes, lungs, subcutaneous | PR | 23 |

| 9 | Subcutaneous and skin | PR | 11 |

| 10 | Inguinal lymph nodes, subcutaneous and skin | PR | 14 |

| 16 | Subcutaneous | PR | 30+ |

| 17 | Bone, liver, lung, subcutaneous | PR | 16+ |

| 19 | Intramuscular | PR | 13 |

| 21 | Lung, subcutaneous | CR | 24+ |

| 25 | Lung, subcutaneous | PR | 2 |

| 26 | Inguinal lymph nodes, liver, subcutaneous | PR | 8 |

| 28 | Axillary lymph nodes, brain | PR | 4 |

| 30 | Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes, intramuscular, subcutaneous | PR | 7 |

| 31 | Liver, lung | CR | 7+ |

| 32 | Skin | CR | 14+ |

| 33 | Lung, subcutaneous | PR | 13+ |

| 34 | Intramuscular, pelvis | PR | 3 |

Abbreviations: PR, partial response; CR, complete response; IL-2, interleukin-2.

Patients 2, 6, and 17 had minor (patient 6) or mixed (patients 2 and 17) responses after a first course of treatment, and were treated with a second course of treatment consisting of ablation, cell transfer and high dose IL-2 therapy prior to achieving an objective clinic response.

Measured from treatment date to time of first recurrence. Patients 16, 17, 21, 31, and 32 had ongoing responses at the time of this writing.

Fig 1.

Lymphodepletion and adoptive cell transfer-induced regression of metastatic disease in diverse anatomic sites. (A) Axillary, pelvic and intraperitoneal metastases (patient 1); (B) extensive liver disease (patient 31); (C) brain and recurrent axillary metastases (patient 28); (D) multiple lung and pelvic metastases (patient 6); (E) lung and subcutaneous disease (patient 21). Pre, pretreatment.

Patients who were treated with lymphodepleting chemotherapy and ACT therapy and who experienced a minor or mixed response, who had stable disease after treatment, or who progressed after a PR were eligible for an additional course of treatment. Three patients experienced an objective clinical response after the second course of treatment (patients 2, 6, and 17). Fourteen other patients received more than one course of lymphodepleting chemotherapy followed by cell transfer and high-dose IL-2 therapy on NCI Surgery Branch protocols. Eight patients who had a mixed or minor response or stable disease after a first course of treatment were re-treated with a second course with the same or a different TIL, and high-dose IL-2 therapy, but did not achieve an objective clinical response after the second course. Six additional patients had received a primary course of lymphodepleting chemotherapy and high-dose IL-2 therapy with cell transfer in prior Surgery Branch protocols without achieving an objective response before their enrollment in this protocol. These cell treatments included administration of cloned T cells (n = 2), nonrapidly expanded TIL (n = 1), peripheral blood-derived cells (n = 1) or gene-modified cells (n = 2). Five of these six patients experienced an objective clinical response to their second cycle of nonmyeloablative chemotherapy that was administered with rapidly expanded TIL and high-dose IL-2 therapy. In all, eight (47%) of the 17 patients treated with a second course including nonmyeloablative chemotherapy and rapidly expanded TIL experienced an objective response, suggesting that multiple courses of treatment are justified in some patients.

In an attempt to identify characteristics of the administered treatments that could predict patient response, many parameters of treatment were compared between the responding and nonresponding patients (Table 5). Characteristics of the lymphocyte cultures were similar in the two groups, and despite comparison of a large number of variables, no statistical difference was detected in any measured parameter of the cultures. Peptide vaccination after cell transfer also had no apparent effect on treatment efficacy, with eight of 17 nonresponders receiving vaccines (three gp100 and five MART-1) and 10 of 18 responding patients receiving vaccine (three gp100 and seven MART-1). The only statistically significant difference was found to be the number of IL-2 doses tolerated (P = .03, Student t test not corrected for multiple comparisons), with the nonresponding patients receiving more doses (mean, 9.6 ± 0.7) than the responding patients (mean, 7.7 ± 0.5). This difference might reflect an increased capacity for cytokine production or pro-inflammatory activities of the infused lymphocytes in vivo in the responding patients that limited their tolerance to high-dose IL-2.

Table 5.

Comparison of Treatments Administered to Patients With OR and NR

| Parameter of Treatment | OR (± SE) | NR (± SE) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 18 | 17 | – |

| Cell No. infused, 109 | 61.3 (± 7.5) | 65.6 (± 12.4) | .76 |

| CD4cells in TIL, % | 18.22 (± 5.8) | 25.41 (± 6.4) | .41 |

| IL-2 doses administered | 7.7 (± 0.5) | 9.6 (± 0.7) | .03 |

| Antigens recognized† | |||

| A | 12 | 10 | |

| G | 3 | 4 | |

| M | 10 | 9 | |

| Tissue of TIL origin‡ | |||

| LN | 5 | 13 | |

| C/SC/IM | 12 | 12 | |

| Visc/other | 3 | 2 | |

| Age of youngest TIL, days | 44 (± 4) | 50 (± 2) | .20 |

| Fold expansion§ | |||

| At 7 days∥ | 191 (± 14) | 165 (± 16) | .23 |

| Total¶ | 1,477 (± 182) | 1,115 (± 128) | .11 |

| Doubling time, days¶ | 2.3 (± 0.5) | 2.1 (± 0.2) | .69 |

| Highest absolute IFN release, pg/mL** |

Abbreviations: OR, objective response; NR, no response; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; IL-2, interleukin-2; A, autologous tumor cells (non-G, non-M); G, gp100:209-217; M, MART-1:27-35; LN, any lymph node; C/SC/IM, cutaneous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular sites; Visc/other, visceral, brain, or bony sites; IFN , interferon- ; REP, rapid expansion protocol.

Two-tailed Student t test assuming equal variance not corrected for multiple comparisons.

The sum of the values is greater than the number of patients because some infused TILs recognized more than one tumor antigen.

Location of tumor mass resected for initiation of TIL culture.

If multiple TIL cultures were infused in a single patient treatment, the most rapidly expanding culture from each patient was used in the calculations shown.

Calculated by determining the ratio of viable lymphocytes 7 days after culture initiation to responder lymphocytes at the time of initiation of the REP.

Calculated by determining the ratio of viable lymphocytes at the time of patient infusion to viable lymphocytes at the initiation of the REP.

Calculated for each infused TIL on the basis of the fold expansion in the final week before cell infusion. If multiple TIL cultures were infused, the most rapidly expanding culture was used for the calculations shown.

All infused cultures exhibited specific tumor recognition as determined by IFN release when stimulated with HLA-A2 cells or autologous tumor cells. The absolute IFN release (pg/mL) as determined typically (but not uniformly) 8 days prior to cell infusion was used in the calculation shown. If multiple TIL cultures were infused or if multiple specificities were exhibited (eg, both HLA-A2 matched and autologous tumor cell recognition), the highest value was utilized for each patient.

Thirteen of the patients who had an objective response to this treatment ultimately progressed at one or more sites after treatment. For nine of these patients, antigen expression by tumor cells was evaluated in pretreatment and recurrent lesions. Recurrent lesions from four patients did not express HLA-A2 and recurrent lesions from one other patient did not express the MART-1 protein (Table 6, Fig 2). These results suggest that ACT therapy exerted a strong selective pressure on the tumor in these patients, and that the transferred cells eliminated antigen-expressing tumor cells by an antigen-dependent mechanism. Ten nonresponding patients had immunocytologically assessable disease before and after treatment; one patient exhibited an apparent loss of antigen expression coincident with cell administration, and two patients had no expression of HLA-A2 before treatment (on retrospective analysis). Seven nonresponding patients expressed HLA, MART-1 and gp100 antigens.

Table 6.

Antigen Loss in Recurrent Lesions of Six Patients Revealed by Immunocytochemistry

| patient | HMB45* |

MART-1 |

HLA-A2 |

W632 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. | Response | Sample† | Site | % | Gr | % | Gr | % | Gr | % | Gr |

| 2 | PR | Pre | Lower neck | 50-75 | 1 to 2+ | 50-75 | 1 to 2+ | Positive | |||

| Post | Lower neck | 25-50 | 1 to 2+ | 25-50 | 1 to 2+ | Negative | |||||

| 10 | PR | Pre | R thigh | 50-75 | 1 to 2+ | <75 | 1+ | Positive | |||

| Post | Liver | 50-75 | 2 | Negative | 50-75 | 2+ | <75 | 2+ | |||

| 19 | PR | Pre | L calf | 50-75 | 2+ | 50-75 | 1+ | Positive | Positive | ||

| Post | L leg | 50-75 | 2+ | 50-75 | 1 to 2+ | Negative | Negative | ||||

| 28 | PR | Pre | R axilla | >75 | 2 | >75 | 1 to 2+ | 75 | 1 to 2+ | >75 | 2 |

| Post | R axilla | >75 | 2+ | 50-75 | 1+ | Negative | Negative | ||||

| 33 | PR | Pre | R ankle | >75 | 2+ | 50-75 | 2+ | >75 | 2+ | >75 | 2+ |

| Post | R ankle | <75 | 2+ | >75 | 1 to 2+ | Negative | Negative | ||||

NOTE. Boldfacing indicates antigen loss.

Abbreviations: Gr, intensity of staining; PR, partial response; pre, before initiation of lymphodepleting chemotherapy; post, after maximum clinical response; R, right; L, left.

Immunocytochemistry of all lesions from any patient was scored by one of two pathologists (A.C.F. or A.A.) according to percentage of positive cells and Gr.

†One representative sample for each time period is shown. Post samples were sampled from a recurrent lesion at the same site as the Pre sample (patients 2, 28, 23, and 33) or at a new site of disease (patients 10 and 19).

Fig 2.

Loss of antigen expression in post-treatment lesions. Tumor cells in pretreatement samples expressed all antigens; however, individual antigens were lost from recurrent lesions. A) MART-1 antigen expression was lost in a recurrent lesion from patient 10. B) HLA-A2 antigen was lost in the recurrent tumor from patient 28. mθ, macrophage.

Toxicity of Treatment

There were no treatment-related deaths. Hematologic toxicities due to the conditioning chemotherapy were transient, and included low RBC and platelet counts requiring transfusions in 34 and 29 patients, respectively (Table 7). Low absolute neutrophil counts (ANCs) and absolute lymphocyte counts, and the extended depression of CD4 lymphocyte counts were observed in most patients. Seven patients experienced opportunistic infections including herpes zoster (n = 3), Pneumocystis carinii (n = 2), and respiratory syncitial virus (n = 1). One patient (the only patient who was seronegative for EBV on entrance into the trial) who experienced greater than 90% regression of cancer and returned to normal function, developed an EBV lymphoproliferative disease four months after treatment and died of this lymphoma eight months later. Several nonhematologic grade 3 and 4 toxicities associated with the lymphodepleting chemotherapy were noted in patients treated with ACT therapy (Table 7). Thirteen patients experienced episodes of febrile neutropenia, and one patient developed cortical blindness secondary to progressive multifocal neuropathy, a rare toxicity associated with fludarabine. Patients also exhibited typical transient toxicities associated with high-dose IL-2 therapy, which were easily managed. There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities attributable to the administration of antitumor lymphocytes. However, 17 patients exhibited autoimmune melanocyte destruction, including twelve patients with vitiligo, three patients with uveitis, and two patients with both vitiligo and uveitis. Uveitis was treated with topical corticosteroid eye drops and all patients’ vision returned to normal. Autoimmune manifestations of treatment were not significantly correlated with objective antitumor responses, although the correlation for patients who received TIL specific for melanocyte differentiation antigens suggested a trend (two-tailed P = .06).

Table 7.

Time in Hospital and Nonhematologic Grade 3 and 4 Toxicities Related to Lymphodepleting Chemotherapy and Cell Transfer

| Patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | % |

| Days in hospital* | ||

| 6-10 | 6 | 17 |

| 11-15 | 18 | 51 |

| 16-20 | 4 | 11 |

| 21-25 | 7 | 20 |

| pRBC transfusions | ||

| 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 1-5 | 18 | 51 |

| 6-10 | 13 | 37 |

| 11-15 | 2 | 6 |

| Platelet transfusions | ||

| 0 | 6 | 17 |

| 1-5 | 21 | 60 |

| 6-10 | 5 | 14 |

| 11-15 | 2 | 6 |

| 16-20 | 1 | 3 |

| Autoimmunity | ||

| Uveitis | 5 | 14 |

| Vitiligo | 13 | 37 |

| Opportunistic infections | ||

| Herpes zoster | 3 | 9 |

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | 2 | 6 |

| EBV-B-cell lymphoma | 1 | 3 |

| RSV pneumonia | 1 | 3 |

| Other | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 13 | 37 |

| Intubated for dyspnea | 3 | 9 |

| Cortical blindness | 1 | 3 |

Abbreviations: pRBC, peripheral red blood cells; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Measured from the day of cell administration to discharge.

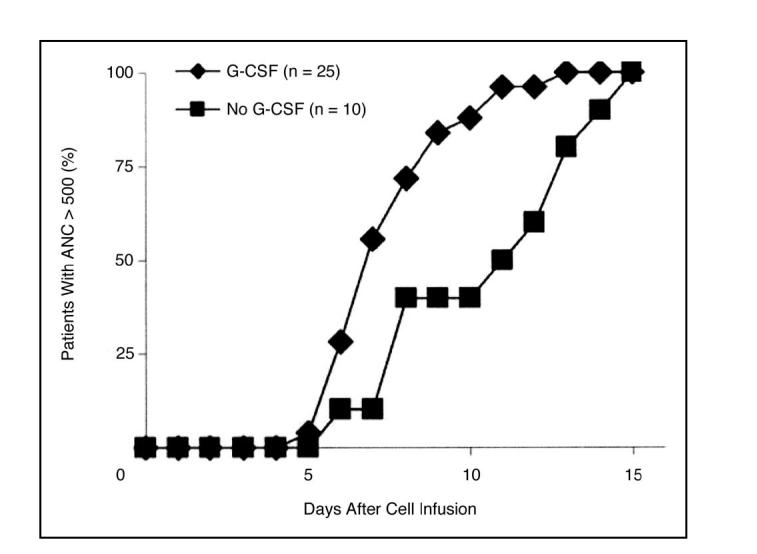

The chemotherapy administered before cell transfer induced a transient depression of neutrophil counts. Because of conflicting information concerning the immunosuppressive impact of G-CSF administration on lymphocyte recovery in allotransplant patients, ten consecutive patients in this study (patients 14 through 23) received cell transfer in the absence of G-CSF administration. No obvious difference in clinical response was observed (4 PR, 6 no response [NR] in the no-G-CSF group compared to 14 PR, 11 NR in the G-CSF group), but G-CSF administration significantly improved neutrophil recovery, as measured by time to recovery of ANC > 500/mm3 (Fig 3) and average ANCs during the recovery phase (not shown).

Fig 3.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) administration significantly improved the time to neutrophil recovery (two-tailed P < .03). The percentage of patients who had recovered neutrophil counts above 500/ mm3is graphed. ANC, absolute neutrophil count

Absolute lymphocyte counts reached their lowest point at a mean value of 17/mm3 (range, 0 to 58 lymphocytes/ mm3) by the day of cell transfer (normal range > 460 cells/mm3). In some patients, a transient lymphocytosis that peaked within the first week after cell transfer was seen (Fig 4). Figure 5shows the analysis of PBL subsets in patients from 1 month to more than 1 year after cell transfer. The average pretreatment CD4+, CD8+, and B-cell counts were within normal limits. However, by 30 to 60 days after treatment, the average CD4+ count fell to 137 cells/mm3, and remained below 200 cells/mm3 for the duration of the study. CD8+ cell counts transiently rose to a maximum of 835 cells/mm3 60 to 90 days after transfer, but decayed to normal levels over time. Like T cells, the B-cell compartment was transiently depleted by the chemotherapy, but B-cell levels returned to the normal range with a few months of treatment in most patients (not shown). Platelet recovery more than 30,000/mm3 and ANC values at normal levels were typically achieved within 2 weeks of cell transfer in the first course of treatment. Interestingly, 17 patients who received a second course of treatment exhibited a significant delay in recovery of platelets, with a median time to recovery increasing from 8 days to 11 days (two-tailed P < 3 × 10-5) and a small (approximately 1 day) delay in neutrophil recovery (two-tailed P = .03). The delayed hematologic recovery after multiple courses of treatment represents a potential impediment to the use of repeated courses of treatment in some patients, although no patient on this study experienced pancytopenia that required administration of their mobilized progenitor cells banked before treatment.

Fig 4.

Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) increased transiently in some patients after adoptive cell transfer. The maximum ALC for each patient within the first 8 days after cell transfer is plotted for all nonresponding patients (NR) and objective responders (OR) who had peak ALC values above a relatively high, arbitrarily chosen value of 1,000 lymphocytes/mm3.

Fig 5.

CD8+lymphocyte counts recovered more rapidly than CD4+lymphocytes. Each symbol represents an individual patient. All available data is included, but measurements were not available for all patients at each time increment. Open symbols represent five patients who were treated with a prior course of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Horizontal lines indicate normal limits. A) Recovery of CD4+cells. B) Recovery of CD8+cells. Bars represent mean values of all patients.

Persistence of Transferred Lymphocytes

The long-term persistence of tumor-reactive T cells from the transferred TIL was investigated using fluorochrome-labeled HLA-A2/peptide tetramers or T cell receptor beta chain variable region (TCR Vβ) family specific antibodies. The use of TCR Vβ family-specific antibodies to follow individual T cell clones is hampered by a lack of a specific antibody to approximately one half of all expressed TCR Vβ families, and interpretation of results is also complicated by endogenous reconstituting lymphocytes that can express the same Vβ as the clone of interest. Several of the patients who exhibited an objective response had received a TIL that contained a predominant T cell clone that was recognized by HLA tetramers or Vβ antibodies. Previous reports11,22 demonstrated that a high frequency of the transferred, tumor-reactive clone was maintained in peripheral blood of a few patients for several weeks after cell transfer. We extended these results by evaluating PBLs from select responding patients sampled months to years after treatment. The relative percentage of the transferred tumor reactive clones derived from the TIL varied widely from patient to patient, and four of the five patients with assessable samples had evidence of long-term clonal persistence (Fig 6). The frequency of MART-1-reactive cells in the PBL of patient 28 changed from a pretreatment level below detection (< 0.1%) to 3.8% of circulating CD8+ cells by day 146 after treatment. Similarly, patient 16, whose administered TIL included a tumor reactive, Vβ1-expressing clone (not shown) demonstrated an increase in circulating Vβ1 cells from a pretreatment value of 4.2% to a level of 8.8% of circulating CD8+ cells 23 months after treatment. Patient 21 had extended persistence of a tumor-reactive Vβ22-expressing clone, with an endogenous pretreatment Vβ22 level of 3.9% that increased 403 days after administration of a Vβ22-containing TIL to 25.5% of circulating CD8+ cells. Most strikingly, 810 days after treatment, a MART-1-reactive, Vβ7-expressing clone from the TIL of patient 10 comprised more than 66% of his circulating CD8+ lymphocytes. We are currently investigating a potential correlation between long-term tumor antigen-reactive lymphocyte persistence and tumor regression in patients treated with ACT using sensitive and quantitative nucleotide sequence based approaches including random amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) analysis.

Fig 6.

Transferred cells persisted for extended time in responding patients. Each tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte administered on day 0 contained a tumor reactive clone with the indicated T-cell receptor beta chain variable region (Vβ) expression or HLA-A2/MART-1-26-35 (27L) tetrameter (A2/MART-1)-binding. The percentage of CD8+ cells recognized by the indicated reagent is indicated. Pre, pretreatment peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL). Post, PBL on the day indicated after cell transfer.

DISCUSSION

The administration of ACT therapy and high-dose IL-2 therapy following lymphodepleting chemotherapy resulted in objective clinical responses in 18 of 35 patients with metastatic melanoma, including 34 patients who were refractory to treatment with high-dose IL-2. Thirteen of the 18 responding patients were also refractory to chemotherapy. Metastatic disease at numerous anatomic sites was susceptible to this therapy, including cutaneous lesions, bulky nodal disease, and visceral, brain, and bony metastases. The toxicities associated with this treatment included the expected toxicities of high-dose IL-2 therapy and the hematologic suppression associated with lymphodepleting chemotherapy; these were mostly transient and readily managed by standard supportive techniques.

Autoimmunity directed against normal melanocytes was observed in nine (75%) of the twelve patients who were treated with T-cell cultures that recognized melanocyte differentiation antigens and who experienced objective tumor regression. Melanocyte destruction in the skin commonly resulted in vitiligo in the responding patients. Similarly, anterior uveitis was detected in four responding patients, and was controlled with corticosteroid eye drops. A link between successful immunotherapy and the onset of autoimmunity has been noted in several clinical immune-based therapies,15,23,24 as well as preclinical immunotherapy models,25 suggesting a strong link between the mechanisms of tumor regression and autoimmune attack on normal tissues. The nature of the melanoma antigen targeted by TIL did not predict the outcome of treatment. Shared tumor antigens such as MART-1 that are expressed by nonmalignant tissues were as effective for targeting melanoma destruction as unique antigens expressed only by the tumor cells. This observation suggests that peripheral mechanisms of self-tolerance (ie, other than thymic deletion) can inhibit the endogenous immune response to tumor, and need to be overcome to induce clinically relevant antitumor responses.

The current protocol incorporated several changes compared to our prior efforts at ACT of patients with melanoma. Improved approaches were developed for the generation of tumor-reactive lymphocyte cultures that often contained multiple clonotypes and a mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ cells.9 In the current trial, 31 treatments contained cells that were selected for tumor recognition and rapidly expanded with OKT3 only a single time, and five treatments (1 PR and 4 NR) contained cells expanded with OKT3 more than once. These cultures contrasted with the unselected TIL26 or the highly selected cloned CD8+ lymphocytes13,18 we administered in prior trials. In previous trials with cloned CD8+ lymphocytes for ACT, the generation of large numbers of cloned cells required at least three expansions mediated by OKT3. The decreased proliferative potential of the cells used in prior trials that were rapidly expanded multiple times in vitro may have accounted for the poor persistence of these cells after cell transfer and their failure to cause tumor regression. A second important change we incorporated into the current protocol was the administration of a conditioning chemotherapy regimen before the cell infusion. This chemotherapy regimen contained agents with little anti-melanoma activity and was designed to deplete endogenous lymphocytes before the cell transfer. The role of lymphodepletion in augmenting the antitumor function of adoptively transferred lymphocytes is an area of active investigation. Two potential mechanisms have been proposed based on studies in preclinical models: the elimination of suppressor T cells,27 or the decreased competition by endogenous lymphocytes for homeostatic regulatory cytokines such as IL-7 or IL-15.7,28,29 The observation of lymphocytosis in some responding patients (Fig 4), together with the suggestion of antitumor T-cell persistence in patients with extended responses (Fig 6) offers hints as to the requirements for successful tumor treatment by ACT therapy. These observations suggest that the capacity for T-cell proliferation in vivo and the transfer into a lymphodepleted host are important determinants of efficacy. More research into these aspects of cell transfer therapy is warranted.

Several variations in administered treatments did not apparently impact the treatment efficacy. Although administration of G-CSF has been reported to be immunosuppressive in patients undergoing allotransplantation of stem cells,30,31 no statistical difference in the response rate was observed in the small, nonrandomized patient populations in this study. Similarly, there were no apparent immunologic or clinical differences between patients receiving a peptide vaccine after cell transfer and those patients who did not receive vaccination. Other aspects of treatment, which are active areas of investigation, include the route of cell administration (intra-arterial v intravenous32), and the dose and schedule of IL-2 administration.33

Some of the patients reported here had extensive tumor regression, but eventually recurred at pre-existing or new sites. Immunocytochemical analysis of pretreatment and recurrent lesions demonstrated a loss of antigen expression by the recurrent tumor in five (55%) of nine patients who relapsed after an objective response. In two patients (patients 2 and 28) the loss of HLA class I antigens observed by immunocytochemical analysis was confirmed by in vitro functional analysis. Melanoma cell lines derived from recurrent tumor biopsies of these patients demonstrated loss of HLA expression (due to mutation of the beta2-microglobulin gene in one patient) and failure to stimulate antigen-specific T cells (not shown). In one patient treated with MART-1 reactive cells, the expression of MART-1 protein was selectively decreased while other melanoma differentiation antigens including gp100 were not affected. These results demonstrate that the transferred T cells exerted a strong selective pressure on the tumor in vivo, and confirm that the antitumor effects of this treatment are antigen mediated.

In summary, the results presented here establish that ACT therapy can impact bulky metastatic melanoma that is refractory to other treatments including high-dose IL-2 therapy and chemotherapy. Fifty-one percent of the patients experienced objective tumor responses with durations from 2 months to more than 2 years, including three patients (9%) with an ongoing complete response. Many aspects of this treatment have the potential to be improved by additional studies of the basic scientific principles of immune-mediated tumor rejection and the optimization of their clinical application. Current studies in our laboratory are focused on the logistical aspects of generating autologous cell-based patient treatments, the genetic modification of lymphocytes with T-cell receptor genes and cytokine genes to change their specificity or improve their persistence, and the administration of antigen specific vaccines to augment the function of the transferred cells.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for the expert cell culture, technical, and data processing assistance provided by Linda Parker, Azam Nahvi, Thomas Shelton, Amy Hubicki, Kevin O’Regan, Mary Ganges, Patti Fetsch, and Melissa Corbett. We are also grateful for the expert patient care provided by the immunotherapy nurses and fellows of the Surgery Branch, the nurses and staff of 2 East of the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, and the Surgical Intensive Care Units of the Center for Cancer Research, the NCI, and Michael Bishop.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:666–675. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberlein TJ, Rosenstein M, Rosenberg SA. Regression of a disseminated syngeneic solid tumor by systemic transfer of lymphoid cells expanded in interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1982;156:385–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, et al. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: Induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg SA, Spiess P, Lafreniere R. A new approach to the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Science. 1986;233:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.3489291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheever MA, Greenberg PD, Fefer A. Specificity of adoptive chemoimmunotherapy of established syngeneic tumors. J Immunol. 1980;125:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.North RJ. Cyclophosphamide-facilitated adoptive immunotherapy of an established tumor depends on elimination of tumor-induced suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1063–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klebanoff CA, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, et al. IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1969–1974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307298101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, et al. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yannelli JR, Hyatt C, McConnell S, et al. Growth of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from human solid cancers: Summary of a 5-year experience. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:413–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960208)65:4<413::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Childs R, Chernoff A, Contentin N, et al. Regression of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma after nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:750–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009143431101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. A phase I study of nonmyeloablative chemotherapy and adoptive transfer of autologous tumor antigen-specific T lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2002;25:243–251. doi: 10.1097/01.CJI.0000016820.36510.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins MB, Kunkel L, Sznol M, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: Long-term survival update. Cancer J Sci Am. 2000;6(suppl 1):S11–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phan GQ, Attia P, Steinberg SM, et al. Factors associated with response to high-dose interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3477–3482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Sakaguchi K, et al. Identification of the immunodominant peptides of the MART-1 human melanoma antigen recognized by the majority of HLA-A2-restricted tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:347–352. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Jennings C, et al. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the human melanoma antigen gp100 by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor regression. J Immunol. 1995;154:3961–3968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley ME, Wunderlich J, Nishimura MI, et al. Adoptive transfer of cloned melanoma-reactive T lymphocytes for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2001;24:363–373. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. The use of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies to clone and expand human antigen-specific T cells. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90210-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fetsch PA, Marincola FM, Filie A, et al. Melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1): The advent of a preferred immunocytochemical antibody for the diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma with fine-needle aspiration. Cancer. 1999;87:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cormier JN, Hijazi YM, Abati A, et al. Heterogeneous expression of melanoma-associated antigens and HLA-A2 in metastatic melanoma in vivo. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:517–524. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980209)75:4<517::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, el Gamil M, Dudley ME, et al. T cells associated with tumor regression recognize frameshifted products of the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene locus and a mutated HLA class I gene product. J Immunol. 2004;172:6057–6064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gratwohl A, Brand R, Apperley J, et al. Graft-versus-host disease and outcome in HLA-identical sibling transplantations for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:3877–3886. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.12.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 2003;100:8372–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overwijk WW, Lee DS, Surman DR, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a “self” antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: Requirement for CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 1999;96:2982–2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1159–1166. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.15.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a persisting tumor/ self-antigen requires CD4+ T dells and fails in the presence of naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma J, Urba WJ, Si L, et al. Antitumor T cell response and protective immunity in mice that received sublethal irradiation and immune reconstitution. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2123–2132. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackall CL, Gress RE. Thymic aging and T-cell regeneration. Immunol Rev. 1997;160:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutella S, Pierelli L, Bonanno G, et al. Role for granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the generation of human T regulatory type 1 cells. Blood. 2002;100:2562–2571. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloand EM, Kim S, Maciejewski JP, et al. Pharmacologic doses of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor affect cytokine production by lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2000;95:2269–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Robbins PF, et al. Cell transfer therapy for cancer: Lessons from sequential treatments of a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2003;26:385–393. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: In vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16168–16173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]