Abstract

Storage symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia, with or without urge incontinence, are characterized as overactive bladder (OAB). OAB can lead to urge incontinence. Disturbances in nerves, smooth muscle, and urothelium can cause this condition. In some respects the division between peripheral and central causes of OAB is artificial, but it remains a useful paradigm for appreciating the interactions between different tissues. Models have been developed to mimic the OAB associated with bladder instability, lower urinary tract obstruction, neuropathic disorders, diabetes, and interstitial cystitis. These models share the common features of increased connectivity and excitability of both detrusor smooth muscle and nerves. Increased excitability and connectivity of nerves involved in micturition rely on growth factors that orchestrate neural plasticity. Neurotransmitters, prostaglandins, and growth factors, such as nerve growth factor, provide mechanisms for bidirectional communication between muscle or urothelium and nerve, leading to OAB with or without urge incontinence.

Key words: Frequency, Incontinence, Instability, Micturition, Unstable bladder, Urgency

Patients with an unstable bladder are defined urodynamically as demonstrating an uninhibitable elevation in intravesical pressure during bladder filling. These patients often share common symptoms, including urgency, frequency, urge incontinence, and nocturia, regardless of etiology. Urodynamics fails to discriminate among idiopathic, myogenic, and neuropathic causes. Moreover, 10%–45% of individuals with unstable bladder contractions may be asymptomatic.1

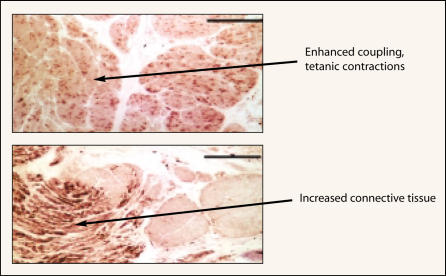

The bladder may be capable of only a limited repertoire of behaviors in response to disease. If that is the case, very different pathologic mechanisms may manifest as the same symptom. Yet the similarity of the symptoms suggests that common factors may underlie the instability. Shared traits exhibited by unstable bladders from humans and those from animals include increased spontaneous myogenic activity, fused tetanic contractions, altered responsiveness to stimuli, and characteristic changes in smooth muscle ultrastructure (Figure 1). Examination of the peripheral innervation and the micturition reflex in models of OAB reveals consistent changes that include patchy denervation of the bladder, enlarged sensory neurons, hypertrophic ganglion cells, and an enhanced spinal micturition reflex. These shared features make it plausible that regardless of the etiology, the underlying causative mechanisms are similar.

Figure 1.

Bladder smooth muscle from patients in unstable bladder demonstrates increased myogenic activity, with fused tetanic contractions and changes in structure. Increased connective tissue between muscle fascicles is reminiscent of that seen with aging, obstruction, and apoptosis due to ischemia. Thus, myogenic changes are commonly seen in the OAB with or without urge incontinence. Reprinted from Morrison J, Steers WD, Brading A, et al. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A (eds). Incontinence, 2nd ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2002.

Electrical Properties of Unstable Detrusor

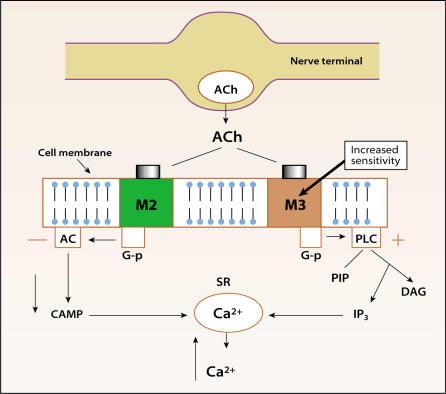

Smooth muscle from unstable bladders often shows enhanced spontaneous contractile activity. This has been documented in human bladder strips from obstructed unstable bladders2 and those patients with neuropathy.3 Altered responses are also seen to stimulation of the unstable detrusor with agonists and to electrical stimulation. Yet there are subtle differences depending on etiology in the patterns exhibited in tissues from unstable bladders. Obstructed bladders are supersensitive to muscarinic agonists and potassium chloride (KCl) (Figure 2). On the other hand, the obstructed detrusor has reduced contraction on nerve stimulation.2,4,5 In idiopathic instability, bladder strips show supersensitivity to KCl but not to muscarinic agonists, and reduced contractile response to electrical stimulation.6 Unstable strips may even be more easily activated by direct electrical stimulation of the smooth muscle,7 showing contractions elicited by stimulation of nerves that are resistant to the nerve-blocking action of tetrodotoxin (TTX).

Figure 2.

Altered responses to stimuli occur in unstable bladders. Obstructed bladders demonstrate hypersensitivity to cholinergic agonists acting at muscarinic (M2 or M3) receptors and increased contractions due to potassium chloride, but reduced electrical evoked contractions. Detrusor tissue from idiopathic instability patients shows increased electrical evoked contractions but normal sensitivity to muscarinic agonists (M3 and M2). Denervated bladders show increased M3 receptor expression. Acetylcholine released from parasympathetic nerves supplying the bladder cause activation of M3 receptors responsible for bladder contraction in humans. The M3 elicited contraction is due to a rise in cytosolic calcium (Ca+2) from intracellular stores. Ca+2 is released from these stores following M3-coupled activation of G-protein (G-p) mediated phospholipase C (PLC) breakdown. Inositol triphosphate (IP3) triggers Ca+2 release from sacroplasmic reticulum (SR). M2 activation causes a fall in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), preventing relaxation. Newer anticholinergics selectively target M3 receptors in the hope of reducing side effects and perhaps increasing efficacy. Reprinted from Morrison J, Steers WD, Brading A, et al. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A (eds). Incontinence, 2nd ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2002.

Smooth muscle bundles in normal detrusor are not as well coupled electrically as those in most viscera. Absent coupling implies that in vivo electrical activity can traverse the length of individual cells without the risk of inadvertently spreading and raising intravesical pressure. To compensate for the absence of coupling, dense innervation allows synchronous activation of the muscle and a rise in intravesical pressure during volitional voiding.

Compared to normal bladders, unstable bladders are better coupled electrically. This allows spontaneous electrical activity to spread and initiate synchronous contractions throughout the detrusor, which explains the fused tetanic contractions seen in unstable bladder strips. In the whole bladder, the increased excitability and greater connectivity of the smooth muscle create foci of electrical activity that could propagate and generate an uninhibited contraction.

Morphologic Changes in the Detrusor

Regardless of the etiology, unstable detrusor develops common changes in the macroscopic structure of the bladder. Unstable human bladders frequently show patchy denervation of the muscle bundles. Some muscle fascicles may be completely denervated, while neighboring bundles appear normal. Other regions may show intermediate innervation.6–9 The areas of reduced innervation become infiltrated with connective tissue.7–9 After complete denervation, hypertrophy of the smooth muscle cells occurs.9 At an ultrastructural level, a common feature in unstable detrusor is the presence of protrusion junctions and ultra-close abutments between the myocytes. This picture is rare in the normal detrusor and may represent the morphologic correlate to increased electrical coupling in unstable bladders.

Neuroplasticity

While myogenic mechanisms are in place to ensure that an inadvertent neural impulse does not trigger a detrusor contraction, the nervous system is designed to ensure that transmission occurs across synapses with a high degree of efficiency. Furthermore, the default mode seems to be to empty the bladder in response to injury or disease, consistent with a role in eliminating toxic waste. The ability of the nervous system to change transmitters, reflexes, or synaptic transmission with disease, injury, or changes in the environment involves neuroplasticity. On the one hand, plasticity may shift the balance toward voiding. However, coexistent conditions such as ischemia may injure nerves so sensation is lost or damage to smooth muscle results in impaired contractility. The net effect could be clinical scenarios such as detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (DHIC) or unstable contractions in the absence of sensation of urgency.

The concept of such a relationship among ischemia, obstruction, aging, and OAB is supported by a recent investigation demonstrating that blood flow to the detrusor smooth muscle was reduced in proportion to the level of decompensation.10 Ischemia, aside from initiating apoptosis of smooth muscle cells, damages intrinsic nerves. Neurons are more susceptible to ischemia than smooth muscle, and such damage is irreversible. Neuronal degeneration is common in obstructed unstable bladders and may contribute to instability.

The patchy denervation suggests the death of some of the intrinsic bladder neurons. Bladder ischemia may occur with severe obstruction or from peripheral vascular disease.4,6 In the hypertrophied detrusor following obstruction, increased metabolic demands11 combined with reduced blood flow can produce anoxia, triggering neuronal death. This could result from obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), urethral stricture, or detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia.

Spinal cord transection and urethral obstruction produce bladder instability and an increase in size of both the afferent neurons in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG)12 and the efferent neurons in the pelvic plexus (after obstruction).13,14 After spinal injury, electrophysiologic measurements reveal a shorter delay in the central transmission of the micturition reflex.15,16 The micturition pathway is reorganized from a spinobulbospinal loop to a predominantly spinal network. Silent C-fiber (unmyelinated) afferents can trigger micturition in unstable bladders, although not in normal bladders. Such reorganization probably occurs in humans, because the ice water test that activates specific cold-sensitive C-fibers fails to evoke micturition in normal subjects but does so in obstructed and neuropathic patients.17,18 Moreover, intravesical administration of selective C-fiber neurotoxins such as capsaicin and resiniferatoxin often eliminates instability.19 It is plausible that the changes associated with OAB are the result of alterations in activity in the nerves controlling the detrusor.

Clinical observations provide a hint that urgency is a separate sensation from that of bladder fullness. Recordings from afferents during bladder filling and contraction20,21 have shown increased activity in a unimodal population of small myelinated and unmyelinated (A-delta and C) fibers in response to intravesical pressure and contraction (Table 1). This implies that there are in-series stretch receptors in the bladder wall whose activity correlates with the sensations of bladder filling and fullness. However, it seems unlikely that fibers with such properties normally mediate the sensation of urgency. Normally the urgent desire to void disappears once voiding begins. Unstable pressure rises may also appear in the absence of sensation. It has been postulated that urgency is triggered by local distortions in the bladder wall, caused by heterogenous activity in some muscle bundles.22 This scenario could develop in normal bladders if a few low-threshold postganglionic parasympathetic neurons were activated by autonomous reflex at the termination of filling. Poor coupling between bundles in normal bladder ensures that such diffuse activity does not raise intravesical pressure. However, it might elicit enough local distortions to activate a subset of nerves that specifically transduce the sensation of urgency. Enhanced coupling in the unstable bladder might permit a wave of diffuse activity, causing urgency and culminating in an involuntary contraction. If coupling is absent, then urgency exists without an intravesical pressure deviation. This hypothesis would explain the efficacy of antimuscarinic drugs in urge incontinence. If only a fraction of ganglia were activated directly by the sensory nerves, suppression of their effects could eliminate both urgency at low volumes and the unstable contractions. Urgency could also result from a lowering of the threshold or spontaneous firing of afferents, as seen in interstitial cystitis (IC) and sensory urgency.

Table 1.

Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Subtypes in Nerves

| Channel | Previous | Gene | Chromosome | Pharmacology | KO phenotype | Abundance in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Symbol | (human) | Adult DRG | |||

| Nav1.1 | Type I | SCN1A | 2q24 | TTX-s | Present | |

| Nav1.2 | Type II | SCN2A | 2q23–24 | TTX-s | Lethal | Present |

| Nav1.3 | Type II | SCN3A | 2q24 | TTX-s | Up-regulated | |

| in axotomy | ||||||

| Nav1.4 | SkM | SCN4A | 17q23–25 | TTX-s | Absent | |

| Nav1.5 | Cardiac | SCN5A | 8p21 | TTX-r | Absent | |

| Nav1.6 | NaCh6 | SCN8A | 12q13 | TTX-s | Abundant | |

| Nav1.7 | PN1 | SCN9A | 2q24 | TTX-s | Abundant | |

| Nav1.8 | SNS/PN3 | SCN10A | 3p21–24 | TTX-r | Partial analgesia | Abundant |

| Nav1.9 | NaN | SCN11A | 3p21–24 | TTX-r | Abundant | |

| Nax | NaG | SCN6A/7A | 2q21–23 | TTX-? | Altered salt intake | Present |

TTX-s, TTX-r, tetrodotoxin-sensitive, -resistant.

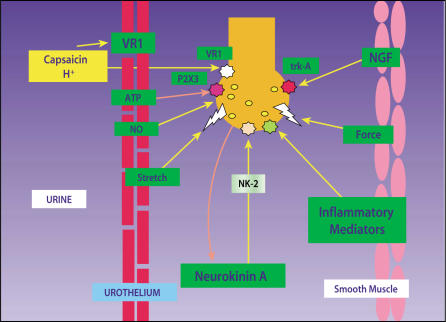

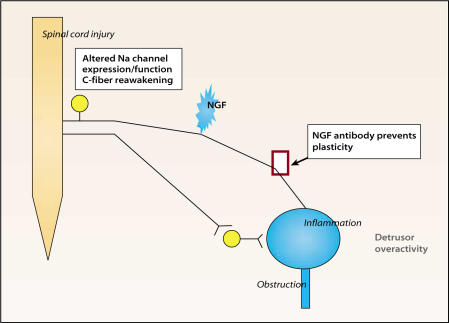

The molecular trigger for changes in the afferents or synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS) may be nerve growth factor (NGF), in addition to other neurotrophins (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophins 3 and 4, glial-derived neurotrophic factor [GDNF]) and cytokines (Figure 3). NGF is responsible for the growth and maintenance of sympathetic and sensory neurons and has been shown to be responsible for neuronal regrowth after injury. NGF is elevated in the bladders of some models of OAB and in those of patients with BPH or IC and idiopathic detrusor instability. In animal models of partial urethral obstruction, chemical cystitis, and spinal cord injury (SCI), pretreatment with antibodies against NGF or its receptor prevents urinary frequency and unstable contractions (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Conversely, intravesical NGF causes unstable detrusor contractions. Gene therapies delivering NGF reverse sensory defects in animal models of diabetes. Blockade of NGF also prevents shared features of neuroplasticity, such as enhanced reflex activity, increased growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43) expression in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and hypertrophy of DRG neurons, in these models. Taken together, these observations suggest that NGF orchestrates some of the neuronal events leading to OAB.

Figure 3.

The urothelium directly communicates with suburothelial afferents acting as luminal sensors. Increased sensitivity of these afferents may lead to overactive bladder (OAB). Low pH, high potassium concentration in the urine, and increased osmolality can influence sensory nerves through mediators such as nitric oxide (NO) and neurokinin A, which acts through NK-2 receptors. H+ ions activate vanilloid (VR-1) receptors, causing pain. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) can activate purinergic P2X3 receptors and modulate sensation. Mice lacking the P2X3 receptor exhibit enlarged bladders and reduced sensation. Inflammatory cytokines and nerve growth factor (NGF) acting at tyrosine kinase A (trk A) receptors can influence the growth, transmitter synthesis, and function of neurons. Sensitization of suburothelial afferents without changes in smooth muscle may result only in urgency. If afferents are sensitized (lower thresholds, spontaneous burst firing) and smooth muscle coupling is enhanced, urgency with unstable contractions may result. Vanilloid, neurokinin, and purinergic antagonists are being examined as possible therapies for OAB and urge incontinence. Reprinted from Morrison J, Steers WD, Brading A, et al. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A (eds). Incontinence, 2nd ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2002.

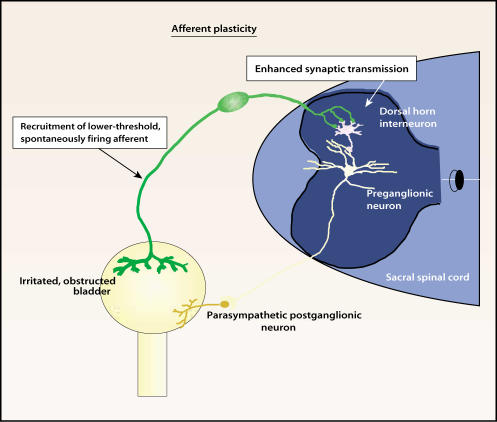

Figure 4.

Sensitization of bladder afferents such as occurs following obstruction or inflammation may lead to enhanced transmission involving second-order neurons in the sacral spinal cord. If preganglionic neurons are not activated, then urgency and frequency without unstable contractions may result. Reprinted from Morrison J, Steers WD, Brading A, et al. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A (eds). Incontinence, 2nd ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2002.

Figure 5.

After transient environmental (ie, intravesical) changes such as inflammation or temporary obstruction, afferents may revert to normal activity. However, if patient is genomically predisposed to OAB (eg, exhibits familial urge incontinence or chronic pain syndromes such as interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, or fibromyalgia) or long-term environmental changes occur, nerve growth factor (NGF) may alter afferents irreversibly. Antibody to NGF or fusion protein against the NGF receptor prevents overactive bladder (OAB) in animal models coincident with alterations in afferents. NGF’s long-term actions may rely on changes in sodium (Na+) channel isoforms expressed by afferents that influence excitability. Most unmyelinated (C-fiber) afferents are not responsive to normal stimuli such as distention or presence of intravesical contents. However, following spinal cord injury, obstruction, or inflammation, activation of the silent C-fibers occurs. The reawakening of silent C-fibers may correspond to changes in Na+ channel expression. Novel approaches to OAB in the future may target the mechanisms leading to these long-term changes. Reprinted from Morrison J, Steers WD, Brading A, et al. Neurophysiology and neuropharmacology. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A (eds). Incontinence, 2nd ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publication Ltd; 2002.

Molecular Basis for Plasticity Due to NGF: Sodium Channel Isoforms

How could NGF produced by a target tissue, as in SCI, obstruction, and inflammation, and then retrogradely transported to the DRG lead to OAB? Recent data suggest that membrane conductance and thus excitability of DRG neurons are altered in models associated with increased access to NGF. This altered conductance is postulated to result from changes in the structure or combination of protein subunits of sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) channels in the cell membrane. A change in Na+ channel isoform appears sufficient to change the properties of afferents. NGF is known to lower the threshold for firing of bladder neurons (hypothetical lower volume threshold for voiding) and induce spontaneous and burst firing (hypothetical unstable contractions, urgency).23 The site of abnormal ectopic firing has been determined to be the DRG, and the firing appears to be due to changes in the isoforms for voltage-gated Na+ channels, which causes spontaneous ectopic discharges. Voltage-gated Na+ channels generate currents during the upstroke of the nerve action potential and are involved in the propagation of the nerve impulse.

TTX binds to and inactivates voltage-gated Na+ channels. Most voltage-gated Na+ channels exhibit rapid inactivation kinetics and sensitivity to nanomolar concentrations of TTX. These Na+ channels are termed TTX-sensitive (TTX-S) (Table 1). Small bladder sensory neurons in the L6-S1 DRG show two types of Na+ currents, a rapidly inactivating TTX-S sodium current (INa) and a slowly inactivating TTX-resistant (TTX-R) INa.

As neurons switch from a quiescent state to high-frequency firing, as with reawakening of C-fibers, they use their Na+ channels differently. But does DRG express a different repertoire of Na+ channels? There is extensive evidence to suggest that α subunits forming the pore of the Na+ channel change in response to environmental conditions and changes in access to NGF. This scenario has been called environmental plasticity associated with channelopathy.

Afferents are the early warning system for the bladder. Yet a substantial number fail to respond to normal environmental stimuli: 61% of sensory nerves innervating the rat bladder are unmyelinated C-fibers, according to findings based on conduction velocities of single dorsal root fibers. The remaining nerves are lightly myelinated A-delta fibers. While 61% of bladder afferents (both A-delta and C) respond to distention of the bladder, no less than a third fail to respond to any mechanical or chemical stimuli. It is tempting to speculate that some forms of OAB derive from recruitment of silent C-fiber afferents. The early warning system is put on full alert. Understanding the switch from quiescent to activated afferents may be the key to understanding OAB and why anticholinergic drugs are not uniformly effective in treating urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence.

Thirty percent of DRG neurons give rise to A-delta fibers that exhibit predominantly TTX-S Na+ currents and are responsible for normal voiding. These cells show low thresholds and short-duration action potentials. At least 60% of bladder DRG neurons are capsaicin sensitive and express the vanilloid receptor (VR-1) (Table 2). Of these DRG neurons, 95% give rise to C-fibers.24 The TTX-R Na+ currents are present in small DRG neurons that are immunoreactive for substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (SP/CGRP), express trk-A, and give rise to C-fibers supplying the bladder.24,25 More than 85% of Na+ currents in small-diameter (C-fiber) DRG neurons corresponding to bladder retrogradely labeled cells exhibit predominantly TTX-R currents. These TTX-R cells demonstrate high thresholds and long-duration action potentials and likely contribute to the higher thresholds for C-fibers. After SCI, obstruction, or cystitis, enhancement of spinal reflexes has been confirmed by abolishment with capsaicin and a positive ice-water test clinically.26 Plasticity occurs in TTX-S and TTX-R Na+ channels as well as in potassium (K+) channels in DRG neurons after SCI, obstruction, or cystitis. With SCI, 60% of dissociated bladder DRG neurons exhibit TTX-S Na+ currents, compared to 30% of such neurons in intact rats.27 IA K+ (low-conductance potassium) currents are also postulated to be reduced, preventing membrane relaxation. These two changes lead to enhanced excitability of C-fibers coinciding with development of a spinal micturition reflex. With cyclophosphamide cystitis, slowly inactivating IA currents in TTX-R neurons are reduced, possibly leading to OAB.27 As further evidence for a channelopathy contributing to OAB, antisense but not sense deoxyoligonucleotides against the (Nav1.8) Na+ channel (TTX-resistant) reduce urinary frequency and unstable contractions in cyclophosphamide cystitis and bladder outlet obstruction and, in a model of idiopathic instability/attention deficit disorder/hypertension, the spontaneously hypertensive rate (SHR).28,29 It is tempting to speculate that the cellular basis for this plasticity is a change in Na+ currents. The molecular basis for this plasticity may be a change in the expression or function of Na+ and K+ channel isoforms. The trigger for plasticity may be NGF or other signaling molecules.

Table 2.

Unmyelinated C-Fiber Terminals in Spinal Cord

| Peptidergic | Nonpeptide |

|---|---|

| NF - | NF- |

| 60% bladder C-fibers | 10% bladder C-fibers |

| IB4 - | IB4/FRAP + |

| SP/CGRP | |

| Trk A-NGF responsive | Trk B-BNDF responsive |

| VR1 | VR1/P2X3 |

| Laminae I/II | Inner laminae II |

| Projection 2nd order to | 2nd order interneurons in |

| brainstem/thalamus | spinal cord |

NF, neurofilament; IB isolectin; SP, substance P; CGRP, calcitonin gene-related

peptide; VR, vanilloid receptor; FRAP, fluorescent acid phosphatase; Trk, tyrosine

kinase receptor; P2X3, P2X3 purinergic receptor; BDNF, brain-derived neu-

rotrophic factor; NGF, nerve growth factor.

There is clinical evidence that Na+ channels play a role in OAB and can be manipulated to treat urgency and frequency. The local anesthetic and nonselective Na+ channel blocker lidocaine can be used to reduce the symptoms of OAB in a variety of conditions, including BPH. Intravesical lidocaine blocks sensory nerve transmission from the human bladder; like subcutaneous lidocaine, it may preferentially act on C-fibers. These are the afferents that give rise to pathologic reflexes such as the ice-water test.30 Intravesical lidocaine increases bladder capacity and reduces involuntary contractions. In a small, uncontrolled study of elderly patients with detrusor instability, the oral Na+ channel blocker mexiletine improved or cured urge incontinence.31

The effects of these agents vary with the disease. Perhaps alterations in Na+ channel expression within nerves are limited to certain types of conditions leading to OAB. Differences in degree of innervation or access to drug could explain differential actions of nonselective local anesthetics that block Na+ channels. In children with neurogenic bladders due to myelodysplasia, Lapointe and colleagues32 found that intravesical lidocaine decreased involuntary contractions in 58% of patients, but increased capacity in 71% of subjects by nearly 60%. Lidocaine increases bladder capacity to the greatest degree in spinal cord-injured patients (230%) compared to its effect in supraspinal neurologic conditions and BPH.33 The first of these conditions is associated with a C-fiber reflex. A reduction in involuntary detrusor contractions is seen only in the first two conditions but not in BPH. In contrast, Reuther and colleagues34 found that elimination of detrusor instability in BPH patients after intravesical lidocaine was predictive of cure of symptoms after transurethral resection of the prostate. In rabbits with obstructed bladders, intravesical lidocaine but not anticholinergics, potassium channel openers, or calcium channel antagonists inhibited hyperreflexia.35 Lidocaine eliminates pain associated with intravesical capsaicin, indicating its ability to inhibit VR-1-expressing afferents found beneath the urothelium. In contrast, intravesical TTX fails to block intravesical capsaicin-induced abdominal licking (a behavioral manifestation of bladder pain) in rats, implying that VR-1-expressing bladder afferents are TTX-R.36 However, targeting Na+ channels expressed by suburothelial nerves may not be as effective as blocking those expressed by spinal nerves. Na+ channels may congregate at points of contact with second-order neurons in the spinal cord. Intrathecal lidocaine and especially bupivacaine eradicate urinary urgency and increase bladder capacity.37 These varied susceptibilities to Na+ blockade suggest that manipulation of Na+ channels expressed by spinal nerves or afferents could influence some disorders of micturition.

Specific Conditions

Outlet Obstruction

The development of a spinal micturition reflex with subsequent OAB occurs in other conditions besides SCI. Bladder outlet obstruction elicits enhancement of a spinal reflex.38 In humans with obstructed bladders, a capsaicin-sensitive spinal reflex can be detected using the ice-water test.39 Urethral obstruction stimulates increased expression of GAP-43, associated with axonal sprouting following injury (Figure 4).40 These observations imply de novo development of new spinal circuits following obstruction. Conversely, relief of obstruction is associated with the reduction of urinary frequency and reversal of these neural changes.40,41This neuroplasticity persists in animals that fail to revert to normal voiding after relief of obstruction.41 Nevertheless, these findings are not mutually exclusive of changes in bladder smooth muscle that are also likely to participate in the development of OAB.42

Bladder outlet obstruction initiates morphologic and electrophysiologic plasticity in afferents via NGF. NGF content is elevated in obstructed bladders in animals and humans, as well as in those with idiopathic instability.43,44 The increase in NGF content precedes the enlargement of bladder neurons and the development of urinary frequency.44 Moreover, blockade of NGF in obstructed animals using autoantibodies prevents neural plasticity and urinary frequency (Figure 5).44

Inflammation

NGF has been shown to be increased in the bladders and urine of patients with IC and also in models of bladder inflammation in animals.45–47 Because NGF orchestrates events during the growth, maturation, and function of visceral afferents, one might anticipate that inflammation of the urinary bladder would be accompanied by neuroplasticity in sensory nerves. Repeated inflammatory stimuli elicit enlargement of bladder DRG neurons.48 Inflammation reduces the activation threshold for bladder afferents.49 Likewise, intravesical NGF lowers the threshold for bladder afferents. Plasticity within the spinal cord may also occur. Chemical or mechanical inflammation of the urinary bladder increases expression of the early-immediate gene C-fos within the lumbosacral spinal cord (Figure 4)50–52 in addition to overexpression of nitric oxide synthase in bladder DRG neurons.

Bladder overactivity induced by inflammation can be inhibited by a fusion protein that prevents interaction between NGF and its tyrosine kinase-A (trk-A) receptor (Figure 5).53 Hence, the neuroplasticity and the potential involvement of NGF in inflammatory conditions resemble those seen in obstruction.

Spinal Cord Injury

Insight into the mechanism underlying the increased mechanosensitivity of C-fibers after SCI has been gained by examining the DRG cells supplying the bladder. Plasticity in these afferents is manifested by enlargement of these cells54 and increased electrical excitability.55 A shift in expression of Na+ channels from a high-threshold TTX-resistant type to a low-threshold TTX-sensitive type occurs after SCI.

Plasticity in bladder afferents after SCI may involve the retrograde transport of substances from either the spinal cord or the bladder to the DRG neuron. Bladder DRG neurons are responsive to a variety of neurotrophins, especially NGF, which has been associated with hypertrophy of bladder DRG cells in a variety of conditions. Indeed, prevention of increased NGF levels in SCI rats prevents hyperreflexia. Alternatively, GDNF may be especially important because a small population of DRG neurons giving rise to C-fibers is nonresponsive to NGF but responds to GDNF.56 It is worth noting that other neurogenic disorders associated with urge incontinence respond to intravesical capsaicin therapy, suggesting that plasticity in C-fiber afferents could form the neurogenic basis for bladder overactivity.57,58,26 The emergence of a spinal reflex circuit activated by C-fiber bladder afferents represents a positive feedback mechanism that may be unresponsive to voluntary control by higher brain centers. The net effect is involuntary urine leakage.

Depression, Anxiety, Attention Deficit Disorder, and OAB

It is probably too simplistic to view OAB with urge UI as just a myogenic or afferent disorder. Certain individuals seem predisposed to OAB. Circumstantial evidence suggests individuals with depression, anxiety, and attention deficit disorder may experience symptoms of OAB more often than the general population. Wolfe and colleagues59 suggested that depression, anxiety, feeding disturbances, pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and changes in voiding are associated with disturbances in brain circuits using specific neurotransmitters, in particular serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT). Fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome are conditions seen more often in patients with IC than the general population,59–63 and these conditions are associated with OAB and possibly with depression, which provides a potential link with 5-HT metabolism. Perhaps the strongest evidence for diminished 5-HT function in depressed patients is the remarkable efficacy of selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in this group of patients. In addition, neuropharmacologic evidence indicates that some forms of depression are associated with abnormalities in the promoter for the serotonin transporter gene.64,65

5-HT also modulates pain and bladder function. Neurons originating in the brainstem raphe nucleus synapse on visceral afferents and preganglionics in the thoracolumbar and sacral spinal cord. These neurons release 5-HT. Stimulation of raphe nuclei in the brain stem inhibits reflex bladder contractions.66 5-HT and its precursors, uptake blockers, or 5-HT analogs inhibit bladder activity in a variety of species.67 The actions of 5-HT are complex and mediated by over 13 different receptors. Some data suggest that 5-HT has a facilitating effect on voiding via modulation of bladder afferents, but intrathecal antagonists of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors reduce the volume threshold for voiding.68 The latter data suggest that descending 5-HT pathways tonically depress bladder afferent input to the sacral spinal cord. Moreover, the 5HT2C agonists MCPP and MK212 inhibit isovolumetric rhythmic bladder contractions.69,70 Taken together, the pharmacologic data suggest that 5-HT acting at some of the 13 receptors in the CNS inhibits micturition reflex pathways. By analogy, a genomic proclivity toward reduced 5-HT neurotransmission in the CNS may enhance bladder activity.

Because 5-HT influences both emotional states and bladder function, are there shared conditions in which this monoamine is altered? An association between depression and bladder complaints has been reported. Zorn and colleagues71 studied 156 consecutive patients presenting to an incontinence clinic and compared their rates of depression to those of a cohort of continent patients. Only 13% of patients with stress incontinence had depression, equivalent to the control cohort. In contrast, 42% of patients with mixed or urge incontinence had depression by history and/or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scoring. Most notably, 60% of patients with idiopathic urge incontinence had either undergone treatment for depression prior to the development of incontinence or scored in the depressive range on the BDI. In a cross-sectional population-based study of 133 incontinent women, Melville and colleagues72 found that nearly a quarter of those with urge UI or mixed UI had depression but only 2% of those with stress incontinence did. These reports suggest that the association of depression with mixed or urge incontinence is significant, but not that with stress urinary incontinence. In the same study by Melville and associates,72 nearly a third of incontinent women had anxiety or panic disorder, compared to none of those with stress UI.

Animal models for depression and anxiety demonstrate OAB. The spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) is a useful animal model for studying hypertension, anxiety, and attention deficit disorder. SHRs void three times as frequently as genetic controls. Awake cystometrograms (CMGs) in SHRs demonstrates unstable contractions. In humans, hypertension is reputedly a risk for OAB due to BPH.73 In addition, a significant proportion of probands with the genetic polymorphism for anxiety disorder have interstitial cystitis.74 Furthermore, many children with attention deficit disorder exhibit diurnal enuresis.75

5-HT can be depleted in the brain by neonatal treatment with clomipramine. Several months after this treatment, rats demonstrate behavioral responses consistent with depression. These animals also void more frequently and have more unstable contractions than controls do. In the clomipramine-treated and SHR models of depression and anxiety, respectively, reduced levels of 5-HT in the brain are associated with lowered volume thresholds for voiding, with unstable bladder contractions. Interestingly, OAB persists in females but not in males following puberty in clomipramine-treated animals. These data support a link among altered 5-HT, emotional disorders, and OAB.

Gender

Recent reviews suggest that OAB and urge incontinence are more common in women than in men and that both conditions are more prevalent at times of changing hormonal levels in women.76 Hormonally induced differences in neurotransmitter systems (eg, by 5-HT) may explain this sexual difference in OAB in the nonelderly. Genetic, psychosocial and biologic factors seem to account for this sexual dichotomy. Estrogen and progesterone appear to influence bladder contractions and voiding frequency.77 Female hormones may also influence nerves. One target of estrogens in the CNS may be 5-HT neurons. This could again link 5-HT, emotional disorders, and OAB in the context of differences between men and women. The serotonergic system plays a major role in depression, although there are other neurotransmitters involved. Differences in 5-HT function may explain why depression is more common in women. Women may be predisposed to both OAB and depression in part because levels of 5-HT in the brain are substantially lower in women than in men.78 When rates of 5-HT synthesis were measured in the human brain using PET, the mean rate of synthesis in normal males was found to be 52% higher than in normal females.

By virtue of reduced 5-HT in the CNS, there may be fewer inhibitory mechanisms for autonomic events such as voiding. This could result in some women in a predisposition to OAB, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and chronic pain states such as IC, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome. The model is too simplistic to provide a universal explanation for all instances of OAB, but the pharmacogenomic basis for these shared traits merits further study.

Conclusion

Alterations in smooth muscle excitability and changes in bladder innervation orchestrated by neurotrophins manufactured by the detrusor are temporally linked with OAB. Direct proof in humans is difficult to obtain, but circumstantial evidence is compelling. The ability of local anesthetics, intravesical afferent neurotoxins, and destruction of afferent nerves in the bladder neck and prostate to reduce urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence indicates an important role for afferent evoked reflexes.79 The detection of a spinal reflex (positive ice-water test) in patients with neurogenic bladders44 and obstruction24 suggests a shared underlying plasticity in nerves supplying the bladder. The molecular basis for this plasticity may be a channelopathy. In addition, genetic or hormonally induced discrepancies may explain the preponderance of OAB and urge UI in middle-aged women and in certain men. The realization that OAB may arise from nerves supplying the smooth muscle with a proclivity toward increased coupling with the detrusor or from altered urothelial function with disease offers an avenue for therapeutic intervention.

Main Points.

There is evidence that overactive bladder (OAB) of different etiology has common causative mechanisms.

Changes in the macroscopic structure of unstable bladder include muscle bundle denervation and smooth muscle cell hypertrophy; ultrastructural changes like protrusion junctions and unusually close abutments between the myocytes are common.

Local anesthetics, intravesical afferent neurotoxins, and destruction of afferent nerves in the bladder neck and prostate reduce urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, indicating an important role for afferent evoked reflexes.

High excitability and connectivity of smooth muscle in the unstable bladder allow propagation of electrical activity that could cause an uninhibited contraction.

Neuroplastic changes associated with OAB may result from alterations in activity in the nerves controlling the detrusor and probably involve nerve growth factor.

OAB often occurs after spinal cord injury or bladder obstruction or inflammation, which may trigger neuroplasticity.

People with depression, anxiety, attention deficit disorder, and other conditions associated with disturbed serotonin metabolism may be predisposed to OAB.

References

- 1.Eckhardt MD, van Venrooij GE, Boon TA. Symptoms, prostate volume, and urodynamic findings in elderly male volunteers without and with LUTS and in patients with LUTS suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2001;58:966–971. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibley GNA. The Response of the Bladder to Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction [DM thesis] Oxford, England: Oxford University; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.German K, Bedwani J, Davies J, et al. What is the pathophysiology of detrusor hyperreflexia? Neurourol Urodyn. 1993;12:335–336. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sibley GNA. Developments in our understanding of detrusor instability. Br J Urol. 1997;80:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brading AF, Turner WH. The unstable bladder: towards a common mechanism. Br J Urol. 1994;73:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills IW. The Pathophysiology of Detrusor Instability and the Role of Bladder Ischemia in Its Etiology [DM thesis] Oxford, England: Oxford University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.German K, Bedwani J, Davies J, et al. Physiological and morphometric studies into the pathophysiology of detrusor hyperreflexia in neuropathic patients. J Urol. 1995;153:1678–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brading AF, Speakman MJ. Pathophysiology of bladder outflow obstruction. In: Whitfield H, Kirby R, Hendry WF, Duckett J, editors. Textbook of Genitourinary Surgery. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998. pp. 465–479. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlton RG, Morley AR, Chambers P, et al. Focal changes in nerve, muscle and connective tissue in normal and unstable human bladder. Br J Urol. 1999;84:953–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schröoder A, Chichester P, Kogan BA, et al. Effect of chronic bladder outlet obstruction on the blood flow of the rabbit urinary bladder. J Urol. 2001;165:640–646. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin RM, Haugaard N, Hypolite JA, et al. Metabolic factors influencing lower urinary tract function. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:171–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.1999.tb00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steers WD, Ciambotti J, Etzel B, et al. Alterations in afferent pathways from the urinary bladder of the rat in response to partial urethral obstruction. J Comp Neurol. 1991;310:401–410. doi: 10.1002/cne.903100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steers WD, Ciambotti J, Erdman S, et al. Morphological plasticity in efferent pathways to the urinary bladder of the rat following urethral obstruction. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1943–1951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01943.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabella G, Berggren T, Uvelius B. Hypertrophy and reversal of hypertrophy in rat pelvic ganglion neurons. J Neurocytol. 1992;21:649–662. doi: 10.1007/BF01191726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse MN, Belton AL, de Groat WC. Changes in bladder and external sphincter function after spinal injury in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:1157–1163. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.R1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Groat WC. A neurological basis for the overactive bladder. Urology. 1997;50:36–52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geirrson G, Lindstrom S, Fall M. The bladder cooling reflex in man—characteristics and sensitivity to temperature. Br J Urol. 1993;71:675–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geirsson G, Lindstrom S, Fall M. The bladder cooling reflex and the use of cooling as stimulus to the lower urinary tract. J Urol. 1999;162:1890–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta P, Chandiramani VA, Beckett A, et al. The effect of intravesical capsaicin on the suburothelial innervation in patients with detrusor hyper-reflexia. BJU Int. 2000;85:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison JFB. Sensations arising from the lower urinary tract. In: Torrens M, Morrison JFB, editors. The Physiology of the Lower Urinary Tract. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namasivayam S, Eardley I, Morrison JFB. A novel in vitro bladder-pelvic nerve afferent model in the rat. Br J Urol. 1998;82:902–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coolsaet BL, Van Duyl WA, Van Os-Bossagh P, et al. New concepts in relation to urge and detrusor activity. Neurourol Urodyn. 1993;12:463–471. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930120504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porreca F, Lai J, Bian D, et al. A comparison of the potential role of the tetrodotoxin-insensitive channels, PN3/SNS and NaN/SNS2, in rat models of chronic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7640–7644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimura N, de Groat WC. Plasticity of Na+ channels in afferent neurones innervating rat urinary bladder following spinal cord injury. J Physiol. 1997;503(Pt 2):269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.269bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DL, Dmietrieva N, Priestley JV, et al. trkA, CGRP and IB4 expression in retrogradely labelled cutaneous and visceral primary sensory neurons in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1996;206:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chai T, Gray M, Steers WD. The incidence of a positive ice water test in bladder outlet obstructed patients: evidence for bladder neuroplasticity. J Urol. 1998;160:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura N, Erdman S, Snider W, de Groat WC. Effects of spinal cord injury or neurofilament immunoreactivity and capsaicin sensitivity in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating the urinary bladder. Neuroscience. 1998;83:633–643. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KS, Dean-McKinney T, Tuttle JB, Steers WD. Intrathecal antisense oligonucleotide against the gene for the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel (Nav1.8) reduces bladder hyperactivity in obstructed rats [abstract] J Urol. 2002;167:34A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KS, Dean-McKinney T, Tuttle JB, Steers WD. Intrathecal antisense oligonucleotides against the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel reduces bladder hyperactivity in the spontaneously hypertensive rat [abstract] J Urol. 2002;167:38A. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edlund C, Peeker R, Fall M. Lidocaine cystometry in the diagnosis of bladder overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20:147–155. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2001)20:2<147::aid-nau17>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castleden CM, Duffin HM, Clarkson EJ. In vivo and in vitro studies on the effect of sodium antagonists on the bladder in man and rat. Age Ageing. 1983;12:249–255. doi: 10.1093/ageing/12.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapointe SP, Wang B, Kennedy WA, Shortliffe LM. The effects of intravesical lidocaine on bladder dynamics of children with myelomeningocele. J Urol. 2001;165:2380. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yokoyama O, Komatsu K, Kodama K, et al. Diagnostic value of intravesical lidocaine for overactive bladder. J Urol. 2000;164:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuther K, Aagaard J, Jensen KS. Lignocaine test and detrusor instability. Br J Urol. 1983;55:493–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1983.tb03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin RM, Hypolite J, Longhurst PA, Wein AJ. Comparison of the contractile and metabolic effects of muscarinic stimulation with those of KCl. Pharmacology. 1991;42:142–150. doi: 10.1159/000138791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lecci A, Giuliani S, Lazzeri M, et al. The behavioral response induced by intravesical instillation of capsaicin rats is mediated by pudendal urethral sensory fibers. Life Sci. 1994;55:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamphuis ET, Ionescu TI, Kuipers PW, et al. Recovery of storage and emptying functions of the urinary bladder after spinal anesthesia with lidocaine and with bupivacaine in men. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:310–316. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199802000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steers WD, Tuttle JB. Immunity to NGF prevents afferent plasticity in the spinal cord following hypertrophy of the bladder. J Urol. 1996;155:379–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steers WD, Ciambotti J, Erdman S, de Groat W. Morphological plasticity in efferent pathways to the urinary bladder of the rat following urethral obstruction. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1943–1951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01943.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chai T, Baker L, Gomez A, et al. Hyperactive voiding in rats secondary to obstruction and relief of obstruction: expression of a novel gene encoding for protein D123 [abstract] J Urol. 1997;157:349A. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steers WD, Kolbeck S, Creedon D, Tuttle JB. Nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder of the adult regulates neuronal form and function. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1709. doi: 10.1172/JCI115488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishizuka O, Mattiasson A, Steers WD, Andersson K-E. Effects of spinal alpha-1-adrenoceptor antagonism on bladder activity induced by apomorphine in conscious rats with and without bladder outlet obstruction. Neurourol Urodyn. 1997;16:191. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1997)16:3<191::aid-nau8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanner R, Chambers P, Khadra MH, Gillespie JI. The production of nerve growth factor by human bladder smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. BJU Int. 2000;85:1115–1119. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steers WD, Tuttle JB. Neurogenic inflammation and nerve growth factor: possible roles in interstitial cystitis. In: Sant GR, editor. Interstitial Cystitis. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowe EM, Anand P, Terenghi G, et al. Increased nerve growth factor levels in the urinary bladder of women with idiopathic sensory urgency and interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol. 1997;79:572–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dupont MC, Spitsbergen JM, Kim KB, et al. Histological and neurotrophic changes triggered by varying models of bladder inflammation. J Urol. 2001;166:1111–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bjorling DE, Jacobsen HE, Blum JR, et al. Intravesical Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide stimulates an increase in bladder nerve growth factor. BJU Int. 2001;87:697–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vizzard MA, Erdman SL, de Groat WC. Increased expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in bladder afferent pathways following chronic bladder irritation. J Comp Neurol. 1996;370:191. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960624)370:2<191::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupont M, Steers W, Tuttle JB. Inflammation induced neural plasticity in autonomic pathways supplying the bladder depends on NGF. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 1994;20:112. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birder LA, Kanai A, Truschel S, et al. Measurement of adrenergic and capsaicin evoked nitric oxide release from urinary bladder epithelium using a porphyrinic microsensor. FASEB Abstr. 1998;98:A122. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrison JFB, Namasivayam S, Eardley I. ATP may be a natural modulator of the sensitivity of bladder mechanoreceptors during slow distensions. 1st International Consultation on Incontinence. In: Khoury S, Abrams P, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. Plymouth, UK: Plymouth Distr. Ltd; 1999. p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bean BP, Williams CA, Ceelen PW. ATP-activated channels in rat and bullfrog sensory neurons: current-voltage relation and single channel behavior. J Neurosci. 1990;10:11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00011.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clemow D, McCarty R, Steers W, Tuttle JB. Efferent and afferent neuronal hypertrophy associated with micturition pathways in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neurourol Urodyn. 1997;16:293–303. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1997)16:4<293::aid-nau5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aguayo LG, White G. Effects of nerve growth factor on TTX- and capsaicin-sensitivity in adult rat sensory neurons. Brain Res. 1992;570:61–70. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90564-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geirsson G. Evidence for cold receptors in the human urinary bladder: effect of menthol on the bladder cooling reflex. J Urol. 1993;150:427–431. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldin AL. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:871–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kruse M, Bray L, de Groat W. Influence of spinal cord injury on the morphology of bladder afferent and efferent neurons. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;54:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00011-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshimura N, de Groat W. Plasticity of Na channels in afferent neurons innervating the rat urinary bladder following spinal cord injury. J Physiol. 1997;503:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.269bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolfe F, Russell IJ, Vipraio G, et al. Serotonin levels, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia, symptoms in the general population. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:980–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neeck G. Neuroendocrine and hormonal perturbations and relations to the serotonergic system in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 2000;113:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bondy B, Spaeth M, Offenbaecher M, et al. The T102C polymorphism of the 5-HT2A receptor gene in fibromyalgia. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:433–439. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Offenbaecher M, Bondy B, de Jonge S, et al. Possible association of fibromyalgia with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2482–2488. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2482::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collier DA, Stober G, Li T, et al. A novel functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene: possible role in susceptibility to affective disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roy A. Suicidal behavior in depression: relationship to platelet serotonin transporter. Neuropsychobiology. 1999;39:71–75. doi: 10.1159/000026563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McMahon SB, Spillane K. Brainstem influences on the para-sympathetic supply to the urinary bladder of the cat. Brain Res. 1982;234:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Downie JW. Pharmacological manipulation of central micturition circuitry. Curr Opin CPNS Invest Drugs. 1999;12:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Espey MJ, Downie JW. Serotonergic modulation of cat bladder function before and after spinal transection. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;287:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steers WD, Albo M, van Asselt E. Effects of serotonergic agonists on micturition function in the rat. Drug Dev Res. 1992;27:361–375. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steers WD, de Groat WC. Effects of m-chlorophenylpiperazine on penile and bladder function in rats. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R1441–R1449. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.6.R1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zorn BH, Montgomery H, Pieper K, et al. Urinary incontinence and depression. J Urol. 1999;162:82–84. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Melville J, Lentz G, Millier J, Fenner D. Impact of depression on symptom perceptions, quality of life and functional status. Abstract presented at the 2001 meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society; October 25–27, 2001; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyle P, Napalkov P. The epidemiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and observations on concomitant hypertension. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;168:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weissman MM, Fyer AJ, Haghighi F, et al. Potential panic disorder syndrome: clinical and genetic linkage evidence. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:24–35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000207)96:1<24::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bhatia MS, Nigam VR, Bohra N, Malik SC. Attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity among pediatric outpatients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991;32:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Archer JS. NAMS/Solvay resident essay award. Relationship between estrogen, serotonin, and depression. Menopause. 1999;6:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ritchie J, Marouf N, Dion SB, et al. Role of ovarian hormones in the pathogenesis of impaired detrusor contractility: evidence in ovariectomized rodents. J Urol. 2001;166:1136–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nishizawa S, Benkelfat C, Young SN, et al. Differences between males and females in rates of serotonin synthesis in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5308–5313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Longhurst PA, Eika B, Leggett RE, Levin RM. Comparison of urinary bladder function in 6 and 24 month male and female rats. J Urol. 1992;148:1615–1620. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36981-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]