Abstract

Pro-α-factor (pro-αf) is posttranslationally modified in the yeast Golgi complex by the addition of α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-linked mannose to N-linked oligosaccharides and by a Kex2p-initiated proteolytic processing event. Previous work has indicated that the α1,6- and α1,3-mannosylation and Kex2p-dependent processing of pro-αf are initiated in three distinct compartments of the Golgi complex. Here, we present evidence that α1,2-mannosylation of pro-αf is also initiated in a distinct Golgi compartment. Linkage-specific antisera and an endo-α1,6-d-mannanase (endoM) were used to quantitate the amount of each pro-αf intermediate during transport through the Golgi complex. We found that α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannose were sequentially added to pro-αf in a temporally ordered manner, and that the intercompartmental transport factor Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor was required for each step. The Sec18p dependence implies that a transport event was required between each modification event. In addition, most of the Golgi-modified pro-αf that accumulated in brefeldin A-treated cells received only α1,6-mannosylation as did ∼50% of pro-αf transported to the Golgi in vitro. This further supports the presence of an early Golgi compartment that houses an α1,6-mannosyltransferase but lacks α1,2-mannosyltransferase activity in vivo. We propose that the α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylation and Kex2p-dependent processing events mark the cis, medial, trans, and trans-Golgi network of the yeast Golgi complex, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

The Golgi complex is an essential organelle of the cell that is required for the posttranslational modification, transport, and sorting of proteins within the secretory pathway. Unlike the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which is a single-membrane system, the Golgi complex appears to be composed of distinct cis, medial, trans, and trans-Golgi network (TGN) cisternal regions as defined by morphological techniques in plant and animal cells (Farquhar and Palade, 1998). These methods define compartments based on their relative position within the Golgi stack, cytochemical staining characteristics, or the localization of resident Golgi enzymes involved in the modification of glycoproteins (Farquhar and Palade, 1981; Kornfeld and Kornfeld, 1985). However, the precise number of functionally distinct Golgi compartments and the boundaries between them are difficult to discern by morphological criteria alone (Mellman and Simons, 1992). This is because the number of cisternae within a Golgi stack can vary from three to >20 in different cell types (Mollenhauer and Morre, 1991), and in some organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Golgi cisternae are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm instead of being organized into a stack (Preuss et al., 1992). In addition, most Golgi enzymes are not restricted to a single cisterna, and where colocalization studies have been performed there is typically some overlap in the distribution of Golgi marker enzymes for different cisternae (Nilsson et al., 1993; Velasco et al., 1993; Varki, 1998). Another potential source of confusion is that a single marker enzyme can show differences in compartmental distribution between different cell lines (Roth et al., 1985; Velasco et al., 1993).

Alternatively, it is possible to examine the posttranslational modification of glycoproteins as they pass through the Golgi complex, which can provide a functional description of how the Golgi complex is organized. In this case, the order of modification events from early to late after synthesis generally correlates to the localization of the corresponding modifying enzymes from cis to trans (Farquhar and Palade, 1981; Mellman and Simons, 1992). The problem with this technique is that it is difficult to determine whether sequential modification events occurring in the Golgi are ordered simply in a biochemical pathway or through compartmentalization of the modifying enzymes. This problem can be overcome through the use of yeast temperature-conditional mutants that exhibit a tight block in intercompartmental protein transport at the nonpermissive temperature (Esmon et al., 1981).

The sec18 mutant has been particularly useful for this analysis, because protein transport ceases almost immediately after shifting these cells to the nonpermissive temperature (Graham and Emr, 1991), and because Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) is a well-characterized cytoplasmic transport factor required for the fusion of transport vesicles with target membranes throughout the secretory and endocytic pathways (Rothman and Wieland, 1996). Sec18p/NSF is part of a 20S fusion particle that includes assembled t-SNARE and v-SNARE complexes (Weidman et al., 1989; Sollner et al., 1993b). ATP hydrolysis by Sec18/NSF facilitates dissociation of the SNARE complex and subsequent membrane fusion between the vesicle and target membrane (Sollner et al., 1993a; Mayer et al., 1996). Therefore, a Sec18p-dependent step in the sequential modification of a glycoprotein implies that a membrane fusion event is required to bring together the glycoprotein substrate and modifying enzyme. This provides a means for determining steps in protein transport in which compartmental boundaries must be overcome.

Modification of N-linked oligosaccharides in the yeast Golgi complex is initiated with the transfer of a mannose residue to the core oligosaccharide by Och1p in an α1,6-linkage (Nakayama et al., 1992). Further elongation by α1,6-mannoslytransferases of the Mnn9 complexes (Jungmann and Munro, 1998) generates an unbranched α1,6-mannan chain of heterogeneous length. Branching of this chain appears to be initiated by an α1,2-mannosyltransferase encoded by the MNN2 gene (Rayner and Munro, 1998). The final carbohydrate modification is the addition of terminal α1,3-linked mannose residues to the branched chain and the ER-derived core by Mnn1p (Raschke et al., 1973). The mating pheromone precursor, pro-α-factor (pro-αf), is also subjected to a proteolytic processing event initiated by the Kex2 protease in a late Golgi compartment (Fuller et al., 1988).

Previous work has indicated that Sec18p is required for the following steps in the maturation and secretion of pro-αf: 1) modification of the ER core-glycosylated form to produce the α1,6-mannosylated form; 2) conversion of the α1,6-mannosylated form to the α1,3-mannosylated form; 3) conversion of the α1,3-mannosylated form to the Kex2p processed form; and 4) exocytosis of the mature peptide (Graham and Emr, 1991). The SEC18 requirement strongly suggests that each modification is catalyzed within a distinct compartment of the secretory pathway and that a vesicle-mediated transport step is required between each modification step. At the time these sec18 experiments were carried out, linkage-specific antisera were available that could distinguish α1,6-mannosylated and α1,3-mannosylated forms of pro-αf. However, the site of α1,2-mannose addition to glycoproteins was not examined in this set of experiments. To examine this modification event, we have partially purified an endo-α1,6-d-mannanase (endoM) from the soil bacterium Bacillus circulans. EndoM specifically recognizes the unbranched α1,6 outer chain of N-linked oligosaccharides and cleaves this oligosaccharide down to an ER-like core form. However, the addition of α1,2-mannose to the outer chain produces an N-linked oligosaccharide that is resistant to endoM (Nakajima et al., 1976). Therefore, the aquisition of endoM resistance can be used to score the transport of glycoproteins to the site of α1,2-mannose addition.

In this study, we have used endoM and linkage-specific antisera to define the kinetics of α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylation of pro-αf. Distinct kinetic intermediates for each of these glycosylation events could be readily identified. Sec18p was required for each step, suggesting that each modification was initiated in a distinct compartment of the Golgi complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Media

Yeast strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. KEX2 was disrupted using pKX::HIS3-S (Redding et al., 1996) or pKX11::hisG-URA3-hisG-1 (Bevan et al., 1998), both gifts from R. Fuller (University of Michigan School of Medicine). Standard rich medium (YPD) (Sherman et al., 1979) was used for culturing of yeast strains. Before cell labeling, strains were grown in Wickerham's minimal proline media (Wickerham, 1946) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract and other supplements as needed. B. circulans was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Minimal salts medium used to grow B. circulans was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of (NH4)2SO4, 400 mg of MgSO4·7H2O, 60 mg of CaCl2·2H2O, 7.54 g of K2HPO4, 2.32 g of KH2PO4, 20 mg of FeSO4·7H2O, 500 mg of yeast extract, and 0.03% d-mannitol in 1 l of distilled H2O and filter sterilizing (Nakajima et al., 1976). To prevent contamination during long incubations in liquid medium, 10 μg/ml streptomycin was added to the culture medium.

Table 1.

Strains used

| Yeast strains | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | Robinson et al., 1988 |

| TBY102 | MATα sec18-1 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | This study |

| TBY130 | SEY6210 kex2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| TGY413-3D | MATα ise1 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his-Δ200 suc2-Δ9 | Graham et al., 1993 |

| XCY42-30D | MATα mnn1Δ::LEU2 ade2-101 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 | Graham et al., 1994 |

| TBY131 | XCY42-30D kex2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| TH2-10D | MATα mnn1 mnn2 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 suc2-Δ9 | Franzusoff and Schekman, 1989 |

| TBY132 | TH2-10D kex2Δ::URA3 | This study |

To prepare α1,6-mannan for endoM induction in B. circulans, TH2–10D (mnn1 mnn2) cells were grown in 10 l of YPD for 2 d at 30°C. Cells (10 OD units/ml) were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended at a ratio of 200 g wet weight to 100 ml of 0.02 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 7.0. The cell suspension was autoclaved for 90 min and then centrifuged at 8000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was removed and stored at 4°C, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 150 ml of the same buffer. The cell suspension was autoclaved and centrifuged again. Supernatants were pooled together, and total carbohydrate was measured by the phenol/sulfuric acid method (Dubois et al., 1956) to yield 500 mg.

To induce endoM expression, α1,6-mannan (mnn1 mnn2) substrate was added into minimal salts medium to a 1% final concentration. B. circulans grows well in a number of media, including Luria–Bertani, but is only induced to secrete endoM in the presence of the α1,6-mannan substrate. To ensure optimal expression of endoM, B. circulans was first grown on minimal salts plates containing 0.5% α1,6-mannan substrate and 2% agar at 30°C. A 10-ml starter culture containing 1% α1,6-mannan substrate was inoculated with a single colony, and after each day of shaking, an aliquot was removed and Gram stained. When 99% of the B. circulans had differentiated from Gram (+) to the Gram (−) form, the starter culture was diluted into 500 ml of the same medium. This culture was shaken for 18 h and centrifuged to remove the bacteria, and the supernatant was adjusted to 10 mM NaN3 and assayed for endoM activity.

Other Reagents

Yeast lytic enzyme was from ICN (Irvine, CA). Expre35S 35S protein labeling mix was from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). Protein A-Sepharose was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Swedan). DE52 cellulose was from Whatman (Maidstone, England). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Preparation of antisera to αf, α1,6-linked mannose and α1,3-linked mannose was previously described (Baker et al., 1988; Graham et al., 1993; Graham and Krasnov, 1995). For immunodepletion of crude α1,3-antiserum, 100 μl of heat-killed XCY42–30D (mnn1) cells were suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 at ∼350 OD units/ml and then added to 500 μl of crude α1,3-sera, rocked at 4°C for 5 min, and centrifuged at 6000 rpm. The supernatant was removed, and the immunodepletion was repeated twice. The specificity was verified by titrating this serum against immunoprecipitated pro-αf from metabolically labeled TBY130 and TBY131 strains.

Colorimetric Assay for endoM Activity

To prepare mannan substrate for assaying endoM activity, a 10-ml sample of α1,6-mannan substrate was adjusted to 0.5 M NaOH with concentrated base, boiled for 10 min, and neutralized with HCl. This β-elimination method removes O-linked mannose. The sample was dialyzed against distilled H20, split into aliquots, and stored at −20°C. The carbohydrate concentration before β elimination was 5 mg/ml and after dialysis was 2.5 mg/ml. Wild-type yeast mannan purchased from Sigma for use in endoM assays was also subjected to β elimination. To assay endoM, enzyme was added to 250 μg of mannan substrate in 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0, 0.01 mg/ml BSA, 0.01 M CaCl2 and 10 mM NaN3 (endoM buffer) in a 500-μl reaction volume and incubated at 50°C for 0.5–5 h. The reaction was terminated by placing samples on ice, adding 1 ml of Nelson–Somogyi reagent 1 (Spiro, 1966), and boiling for 30 min. One milliliter of reagent 2 (Spiro, 1966) was added to samples on ice, and the absorbance was measured at 562 nm to quantitate the reduced mannose released from substrate. Mock-treated substrate was used for background subtraction, and fresh medium was used as a blank when assaying spent supernatant from B. circulans cultures. One unit of endoM is defined as the amount that will release 1 μmol of mannose per 30 min of incubation at 50°C.

Partial Purification of endoM

The supernatant from 500 ml of B. circulans culture was adjusted to 30% of saturation with ammonium sulfate at 4°C. After 30 min of stirring and 1 h of standing, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was adjusted to 60% of saturation with ammonium sulfate, stirred for 30 min, and allowed to settle for 2 h. A second centrifugation at the same settings was performed, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 10 mM NaN3. The sample was dialyzed against the same buffer for 24 h. One-half of the dialyzed sample was loaded onto a DE52-cellulose column (2.5 × 19 cm) equilibrated with buffer and eluted using a 0–0.6 M NaCl gradient at a 0.5 ml/min flow rate. A final 0.75 M NaCl wash (10 ml) was also collected. Fractions (5 ml) were assayed for endoM activity and protein concentration and displayed a profile similar to that previously reported (Nakajima et al., 1976). Active fractions were pooled together, dialyzed, and concentrated as previously described (Nakajima et al., 1976). One-milliliter aliquots were refrigerated at 4°C, and the preparation was found to retain 80% of the original activity after 1 y of storage.

Pulse–Chase Labeling and Immunoprecipitation

Cell labeling and primary immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described (Graham and Emr, 1991). For secondary immunoprecipitations, samples were dissociated from the primary antibody and reimmunoprecipitated as previously described (Graham et al., 1993). For endoM treatment of immunoprecipitates, the protein A-Sepharose immune complex pellet was washed in 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0, dried, and resuspended in 24 μl of endoM buffer. Samples were incubated for 2.5 h at 50°C with 50 mU of endoM, except where other conditions are defined in the figure legends. Reactions were terminated with 4× Laemmli buffer and electrophoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were analyzed by autoradiography or a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, CA) PhosphorImaging system using IPLabgel-H software (for Macintosh) (Signal Analytics, Vienna, VA). We estimated the amount of mannan in pro-αf immunoprecipitates to be ∼0.015 μmol, whereas the amount of mannan in a standard Nelson–Somogyi assay reaction was ∼1.5 μmol.

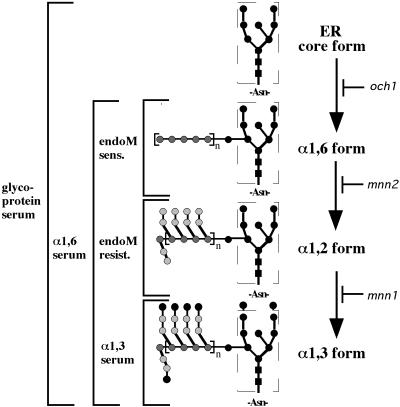

The relative amount of α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylated intermediate forms in pro-αf immunoprecipitates was determined as described below and as diagrammed in Figure 1. After elution of αf from the primary immunoprecipitate, one-third of the eluate was reimmunoprecipitated with αf-antiserum and saved for gel electrophoresis to show the distribution of all labeled αf forms present in the original sample. The remaining two-thirds of the eluate were immunoprecipitated with α1,3-linkage-specific antiserum to quantitatively remove all α1,3-modified pro-αf. The supernatant from this latter immunoprecipitation was then subjected to a third immunoprecipitation with α1,6-linkage-specific antiserum to collect the remaining pro-αf that was Golgi modified, a mixture of α1,6- and α1,2-modified intermediates. The α1,6-immunoprecipitates were split equally with the pro-αf bound to protein A-Sepharose beads and resuspended in endoM buffer. One-half was treated with endoM (50 mU) as described above, whereas the other half was left untreated. An equivalent portion (1.5 OD equivalents) of each immunoprecipitate was electrophoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Figure 1.

Method for defining the biosynthetic intermediates of pro-αf. Our nomenclature for the pro-αf biosynthetic intermediates is shown to the right, and the method for defining the intermediates is to the left of the structures. Briefly, all forms are recognized by the primary antiserum. The α1,6-linkage-specific serum recognizes all Golgi mannosylated forms, whereas the α1,3-linkage-specific serum only recognizes the terminal α1,3-mannosylated form. EndoM-sensitive (sens.) pro-αf forms carry unbranched α1,6-mannan chains, whereas endoM-resistant (resist.) forms have been branched with α1,2-mannose. Each step is defined genetically by mutants lacking each mannose modification as indicated.

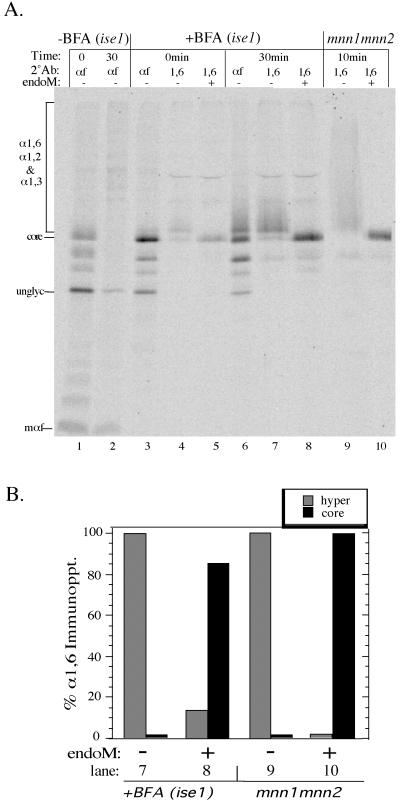

Quantitation of percent hyperglycosylated versus percent core glycosylated was carried out by using IPLabgel-H. Segments were drawn around each lane to be analyzed as shown in Figure 5B. The phosphorimage signal above the core form was referred to as “hyperglycosylated,” whereas the signal found within the area of the core form was referred to as “core.” The background subtracted from the total phosporimage signal was set based on the areas of each lane above and below the glycoprotein smear. All samples treated with or without endoM were equivalently loaded within ≤1% difference as determined by quantitation of total signal in each lane.

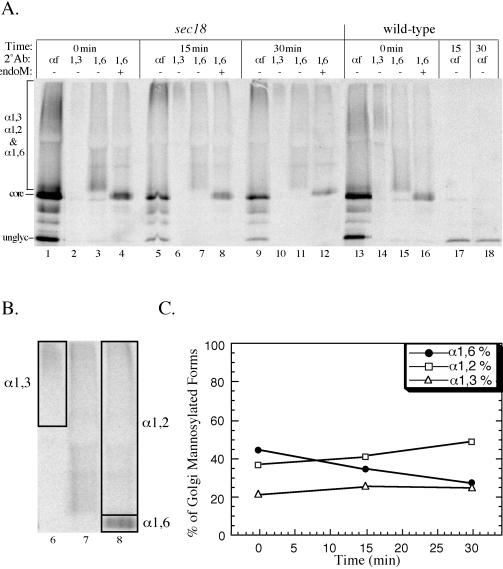

Figure 5.

Sec18p is required for the formation and consumption of each pro-αf intermediate form. Wild-type (SEY6210) and sec18 (TBY102) cells were labeled at 20°C for 7 min and shifted to 37°C for a 30-min chase. The secondary immunoprecipitations and endoM treatment were performed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS section. All samples (1.5 OD equivalents) were electrophoresed in 15% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by phosporimaging. (B) The area of the lanes used to quantitate the α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylated forms from the 15-min time point is boxed. (C) Quantitation of α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylated pro-af forms at each time point for the sec18 samples. Each value is the average from three independent experiments.

In Vitro Transport

Yeast semi-intact cell membranes and cytosol were prepared from strain RSY607 (Pryer et al., 1992) as previously described (Baker et al., 1988). One-stage transport reactions were performed in the presence of [35S]methionine-labeled prepro-αf and an ATP-regenerating system at 23°C for indicated times. Reactions were stoppped by the addition of SDS to 1%, and glycosylated forms of labeled pro-αf were precipitated with concanavalin A linked to Sepharose or α1,6-linkage-specific serum coupled to protein A-Sepharose. Precipitates were incubated with or without endoM as previously mentioned.

RESULTS

Induced Expression and Purification of endoM

As previously reported (Nakajima and Ballou, 1974; Nakajima et al., 1976), endoM is expressed and secreted by B. circulans in the presence of unbranched α1,6-mannan. A source of this substrate was obtained by extracting cell wall mannan from an S. cerevisiae mnn1 mnn2 strain that is deficient in adding α1,2-linked and α1,3-linked mannose to N-linked oligosaccharides (Raschke et al., 1973). To our surprise, we found that B. circulans is a Gram-variable bacterium that is predominantly Gram (+) during logarithmic growth. During stationary phase, these bacteria slowly differentiate into a Gram (−) form, and it is only the Gram (−) form that can be induced to secrete endoM. To obtain an optimal yield of endoM, a small B. circulans culture (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) was grown to stationary phase and shaken for 1 wk or until 99% of the bacteria in the culture were Gram (−). The starter culture was used to inoculate a larger culture containing 1% α1,6 -unbranched mannan substrate which was shaken until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached (18 h). The cells were removed by centrifugation, and the spent supernatant was assayed by the Nelson–Somogyi colorimetric method (Spiro, 1966) and found to contain 1200 U of endoM activity with a specific activity of 1.4 U/mg protein. The culturing method described here provided a sixfold increase in the specific activity of the starting material relative to a published report (Nakajima et al., 1976). The endoM was partially purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and anion exchange (DE52) chromatography (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Active fractions from the DE52 column were combined, concentrated, and assayed to yield 430.5 U (13.5 U/mg protein).

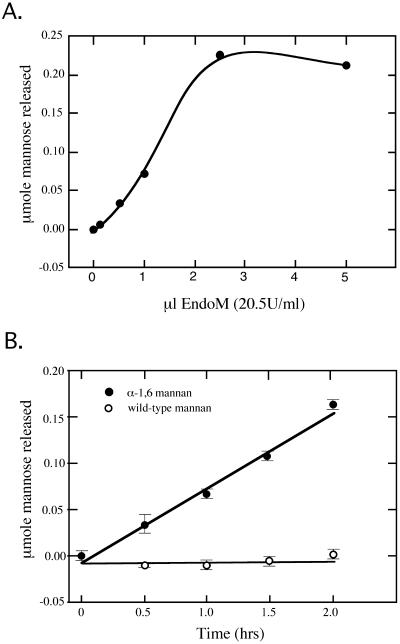

To use endoM to distinguish α1,6- and α1,2-mannosylated forms of glycoproteins, it was essential to determine the conditions required to give complete digestion of sensitive forms and to demonstrate the specificity of the enzyme preparation. The final endoM preparation was first titrated against a constant amount of α1,6-mannan substrate (250 μg) and was found to saturate the reaction at ∼50 mU of enzyme in a 2-h incubation (Figure 2A). To assess the specificity of the endoM, mannan from wild-type cells or mnn1 mnn2 cells was incubated with 40 mU of endoM for the times listed in Figure 2B. Release of mannose from the α1,6-mannan was linear over this time range. In contrast, the wild-type mannan was completely resistant to endoM digestion (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Activity and specificity of purified endoM against a crude mannan substrate. Release of reduced mannose from a mannan substrate was measured using the Nelson–Somogyi colorimetric assay. (A) 250 μg of mannan substrate (per reaction) prepared from strain TH2-10D (mnn1 mnn2) were incubated with an increasing amount of purified endoM for 2 h at 50°C. The reaction was saturated with ∼50 mU of enzyme. (B) 250 μg of mannan prepared from mnn1 mnn2 cells (closed circles) or wild-type cells (open circles) were incubated with 40 mU of endoM for the time points indicated. The mnn1 mnn2 strain produces α1,6-mannan lacking α1,2- or α1,3-linked mannose.

To determine whether the endoM preparation could be used to distinguish different N-linked oligosaccharide forms of a specific glycoprotein, we immunoprecipitated pro-αf from 35S metabolically labeled yeast cells and treated the samples with endoM. The α-factor mating pheromone is initially synthesized as a high-molecular-weight precursor that is cotranslationally modified with three N-linked oligosaccharides to produce the 26-kDa core glycosylated ER form (Fuller et al., 1988). Further modification of the N-linked oligosaccharide with specific mannose residues (α1,6 → α1,2 → α1,3-linkage) occurs as pro-αf is transported through the Golgi complex (Herscovics and Orlean, 1993) and results in a smear of hyperglycosylated precursor forms (26–150 kDa) by SDS-PAGE. The nomenclature we use to describe the N-glycan biosynthetic intermediate forms is shown in Figure 1. Within the TGN, the endoprotease Kex2p initiates proteolytic processing of pro-αf to four mature peptides that are ultimately secreted into the media (Bussey, 1988; Fuller et al., 1988).

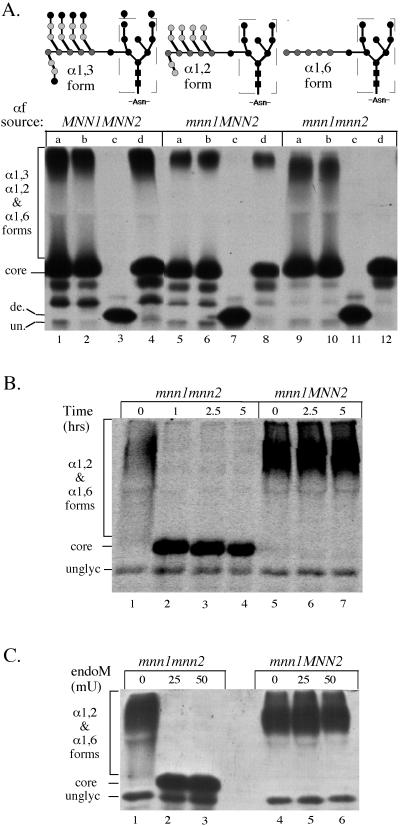

To test whether endoM would recognize α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf, we labeled MNN1 MNN2 kex2Δ, mnn1 MNN2 kex2Δ, and mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ strains for 10 min at 20°C. KEX2 was disrupted in each strain to prevent proteolytic processing of pro-αf to increase the yield of this precursor. These strains should produce the α1,3-, the α1,2-, and the α1,6-mannosylated forms of pro-αf, respectively (Figure 3A). Pro-αf was recovered from each strain by immunoprecipitation, eluted from primary antibody, and split into four equal samples. One sample was left untreated (Figure 3A, lanes marked a), and the others were incubated with buffer alone (lanes marked b), the ammonium sulfate endoM preparation (lanes marked c), or the final endoM preparation (lanes marked d). The ammonium sulfate preparation clearly contained an undesired endoglycosidase activity (Figure 3A, lanes marked c), which completely removed the N-linked oligosaccharides from pro-αf to produce a deglycosylated form. Purification of endoM by ion exchange chromatography removed this contaminating endoglycosidase activity as indicated by the inability of the final endoM preparation to convert pro-αf to a deglycosylated form (Figure 3A, lanes marked d). As expected, most of the pro-αf produced in wild-type and mnn1 kex2Δ cells was resistant to endoM (Figure 3A, lanes 4 and 8). In contrast, the hyperglycosylated smear of pro-αf produced from an mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ strain was completely digested to a core-like form when incubated with DE52-purified endoM (Figure 3A, lane 12). This result demonstrates that the endoM recognizes the α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf, whereas further modified forms are resistant to endoM digestion.

Figure 3.

Activity and specificity of endoM preparations against immunoprecipitated pro-αf. (A) MNN1 MNN2 (TBY130), mnn1 MNN2 (TBY131), and mnn1 mnn2 (TBY132) strains were labeled with 35S-amino acids for 10 min at 20°C and no chase. N-linked oligosaccharides produced from these yeast strains are represented above each genotype. Pro-αf was recovered from the cell lysates by immunoprecipition and was split into four equal samples. One sample was left untreated (lanes marked a), and the other samples were treated with the following preparations: (b) endoM buffer (mock), (c) ammonium sulfate-purified endoM (50mU), and (d) DEAE-purified endoM (50 mU). All subsequent enzyme incubations are with DEAE-purified endoM. (B and C) Pro-αf was immunoprecipitated from mnn1 and mnn1 mnn2 yeast strains labeled at 20°C for 10 min and chased for 7 min. (B) Samples were split and treated with 50 mU of endoM for the indicated times. (C)Samples were split and treated with the indicated amount of endoM. de., deglycosylated pro-αf; un., unglycosylated pro-αf. Note that the contaminating endoglycosidase apparent in lanes marked C produces a deglycosylated pro-αf with a slightly slower mobility than the unglycosylated form. This suggests cleavage between the N-acetylglucosamines leaving behind one sugar per N-linked oligosaccharide. Core indicates the ER pro-αf form carrying the oligosaccharide shown within the dashed box. All three experiments were electorphoresed on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels with B and C run for shorter times than A.

To ensure that the endoM incubation conditions would give complete digestion of all α1,6-modified pro-αf, we examined the effect of changing the incubation time and amount of endoM in the reaction. Pro-αf was immunoprecipitated from mnn1 MNN2 kex2Δ and mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ strains labeled for 7 min and chased for 10 min so all of pro-αf would be chased to its final modified state. Treatment of these samples with 50 mU of endoM resulted in complete digestion of pro-αf from the mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ strain within 1 h (Figure 3B, lane 2), whereas the resistant form produced from the mnn1 MNN2 kex2Δ strain remained unchanged for up to 5 h of incubation (Figure 3B, lanes 5–7). Reducing the amount of endoM to 25 mU still gave complete digestion of the sensitive forms (Figure 3C, lane 2) whereas 10 mU digested most, but not all, of the pro-αf produced from mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ cells (our unpublished data). Importantly, all of the radiolabeled pro-αf from the mnn1 kex2Δ strain was resistant to endoM, indicating an efficient conversion of all pro-αf to the α1,2-mannosylated form during transport through the Golgi. Likewise, all of the pro-αf chased to the α1,6-mannosylated form in the mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ strain, indicating this modification event was also efficient. The results from Figure 3 indicate that a 2.5-h incubation with 50 mU of endoM was at least a fivefold overdigestion, and that no contaminating endoglycosidase or protease activity was observed in these reactions. These reaction conditions should ensure that all resistant forms remaining after treatment are the result of α1,2-mannosylation rather than incomplete digestion of sensitive forms.

Identification of α1,6- and α1,2-Mannosylated pro-αf Transport Intermediates in Wild-Type Cells

If α1,6- and α1,2-linked mannose are added to glycoproteins in sequential compartments of the Golgi complex, then it should be possible to detect these intermediate forms in a pulse–chase experiment. In fact, the smear of hyperglycosylated pro-αf produced from MNN1 MNN2 kex2Δ and mnn1 MNN2 kex2Δ cells that migrated just above the core form shown in Figure 3A (lanes 4 and 8) disappeared when treated with endoM. This suggested that these strains produced an α1,6-intermediate pro-αf form that had not yet been transported to a compartment that contains the α1,2-mannosyltransferase. To slow protein transport so biosynthetic intermediates could be more easily observed, MNN1 MNN2 kex2Δ cells were metabolically labeled at 15°C for 5 min and chased at 15°C for the time points indicated in Figure 4A. Pro-αf was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates and subjected to a second round of immunoprecipitation with α1,6-linkage-specific antiserum. The second immunoprecipitation isolated all Golgi-modified pro-αf forms and removed the ER core glycosylated pro-αf form, which can obscure the product of endoM digestion. Half of each sample was then subjected to endoM treatment to determine the half-time of α1,2-mannosylation.

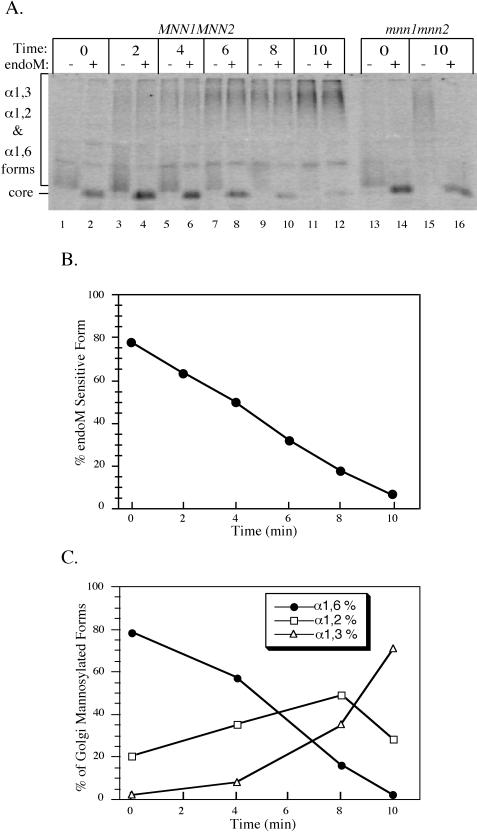

Figure 4.

Sequential modification of pro-αf in the Golgi complex. (A) kex2Δ cells (TBY130) were labeled at 15°C for 5 min and chased for the times indicated. Pro-αf was immunoprecipitated first with αf serum and then with α1,6-linkage serum and split in half for treatment with or without endoM. mnn1 mnn2kex2Δ (TBY131) cells were also labeled and pro-αf analyzed as described above. (B) Quantitation of the data in A was carried out using a phosphorimager. Forms resistant to endoM are a mixture of α1,2- and α1,3-mannosylated pro-αf, whereas sensitive forms are only α1,6-mannosylated. (C) The kex2Δ strain TBY130 was labeled and chased as above. The intermediate forms were quantified as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS section and shown in Figures 1 and 5. The data shown are from a single experiment but are representative of data obtained in three independent experiments.

At the beginning of the chase period, most (78%) of the pro-αf that had arrived in the Golgi complex was sensitive to endoM digestion (Figure 4, A and B, 0 min), indicating that most of this glycoprotein had not yet encountered the α1,2-mannosyltransferases. Over the 10-min chase period, the labeled pro-αf became completely resistant to endoM digestion, displaying a 3 min half-time for conversion to endoM resistance (Figure 4, A and B). As a control for the endoM treatment, pro-αf that was immunoprecipitated from mnn1 mnn2 kex2Δ cells was still endoM sensitive after the 10-min chase period (Figure 4A, lanes 13–16).

The endoM-resistant pro-αf forms in Figure 4A should actually represent a mixture of α1,2- and α1,3-mannosylated forms, so additional pulse–chase experiments were performed to examine the kinetics of α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylation of pro-αf. After the primary pro-αf immunoprecipitation, the samples were eluted and subjected to a second immunoprecipitation with α1,3-linkage-specific antiserum. The pro-αf remaining in the supernatant was then immunoprecipitated with the α1,6-linkage-specific antiserum, and half of this sample was endoM treated. Figure 4C shows the percent of total Golgi-modified pro-αf at each chase time that is in the α1,6-mannosylated form, the α1,2-mannosylated form, and the α1,3-mannosylated form. The half-time for conversion of α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf to further modified forms was slightly >4 min in this experiment. It is clear that at the 4-min time point there was very little pro-αf carrying α1,3-mannose, so the endoM-resistant pro-αf present at this time was nearly entirely in the α1,2-mannosylated form. In fact, the half-time for α1,3-mannosylation of pro-αf was ∼9 min. These results indicate that with the pulse–chase regimen used in these experiments, the half-time for conversion of α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf to the α1,2-mannosylated form is ∼4 min, and that an additional 4–5 min is required to convert half of the α1,2-mannosylated form to the α1,3-mannosylated form. Therefore, these Golgi mannosylation events are ordered temporally.

Sec18p Is Required for Transport of pro-αf through the α1,2-Mannosyltransferase Compartment

The low-temperature pulse–chase experiments described above suggests that α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylation of pro-αf might occur in sequential Golgi compartments. To further test whether these modifications occur in distinct compartments and to ask whether vesicle-mediated transport is required for the formation and consumption of these biosynthetic intermediates, we took advantage of the protein transport block exhibited by the sec18 mutant. Wild-type and sec18 cells were labeled at the permissive temperature (20°C) for 7 min to mark all of the compartments of the Golgi complex with pro-αf intermediate forms. In both sec18 and wild-type cells, all of the different biosynthetic intermediates of αf (from the ER core form to the secreted mature form) can be seen at the end of the permissive temperature labeling period (Graham and Emr, 1991). The wild-type and sec18 cells were then chased and immediately shifted to 37°C to inactivate Sec18p in the mutant cells. Transport and processing of pro-αf was unaffected when wild-type cells were shifted to 37°C. Therefore, all of the labeled pro-αf disappeared as it was processed and secreted into the medium in the mature form (Figure 5A, lanes 17 and 18; our unpublished data).

The distribution of pro-αf forms in sec18 mutant was similar to that in the wild-type cells after the labeling period at the permissive temperature, indicating that transport and modification was unaffected at this temperature. However, pro-αf was blocked from further transport during the nonpermissive chase in the sec18 cells (Figure 5A, compare lanes 1, 5, and 9 with lanes 13, 17, and 18). The linkage-specific antisera and endoM were then used to quantitate the amount of each pro-αf biosynthetic intermediate at each time point (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). An example (Figure 5A, lanes 6–8) of the the areas used in the quantitatation of each mannosylated form is shown in Figure 5B. From three experiments, we found an average of 44% of pro-αf from the sec18 cells was in the α1,6-mannosylated form (endoM sensitive) at the time the cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature (Figure 5, A, lane 4, and C). The percentage of α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf dropped to 28% (a 16 ± 5% change) over the 30-min chase at 37°C. This loss of the α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf was compensated primarily by an increase in the α1,2-mannosylated form. After inactivation of Sec18p, the half-time for conversion of the α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf to the α1,2-mannosylated pro-αf was extrapolated to be 43 min. The half-time for this event in wild-type cells was too rapid to measure at 37°C but was ∼4 min at 15°C (see Figure 4). Thus, there is clearly a Sec18p requirement for conversion of the α1,6 form to the α1,2 form. The slow increase in the formation of α1,2-mannosylated pro-αf may represent some “leakiness” in the sec18 block but more likely represents a low level of α1,2-manosyltransferase activity within the α1,6 compartment. Finally, the percent of α1,3-mannosylated pro-αf did not change significantly over the chase period (Figure 5, A and C). Therefore, we conclude that Sec18p is also required for the conversion of the α1,2-mannosylated pro-αf form to the α1,3-mannosylated form. The Sec18 dependence for these events strongly suggests that the α1,6-, α1,2-, and α1,3-mannosylation and proteolytic processing of pro-αf occur in separate Golgi compartments.

Brefeldin A-treated Cells Accumulate Core Glycosylated and α1,6-Mannosylated pro-αf

Brefeldin A (BFA) is a specific inhibitor of ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) and its exchange factors (Peyroche et al., 1999). Treatment of yeast cells with 75 μg/ml BFA inhibits most ER to Golgi protein transport, but some pro-αf leaks through the first block and accumulates behind a second block within the yeast Golgi complex. The pro-αf that reaches the Golgi aquires α1,6-mannose but does not acquire α1,3-mannose. Although BFA induces the retrograde movement of Golgi enzymes to the ER in mammalian cells, there is no indication that BFA causes a comparable redistribution of yeast Golgi enzymes to the ER, or that Golgi-specific modifications can be catalyzed within the yeast ER (Graham et al., 1993). To determine whether pro-αf received α1,2-mannose in the presence of BFA, BFA-sensitive cells (ise1) were labeled for 7 min and chased for 30 min in the presence or absence of 75 μg/ml BFA. Pro-αf intermediates were immunoprecipitated from cells chased for 0 or 30 min and then split in half, and one portion was treated with endoM (Figure 6A). Quantitation of the electrophoresed samples indicated that 85% of the Golgi-modified forms produced in the BFA-treated cells were sensitive to endoM (Figure 6B). The amount of endoM-resistant forms (15%) was slightly higher than the background of apparent endoM-resistant pro-αf forms immunoprecipitated from an mnn1 mnn2 strain (Figure 6, A and B, compare lanes 8 and 10). This can be attributed to an incomplete block in transport as well as a nonspecific band contaminating the BFA-treated samples (Figure 6A, lanes 4, 5, 7, and 8). These results indicate that a BFA block occurs beyond the α1,6-mannosylation step and before the α1,2-mannosylation step. This is in addition to an apparent block in ER to Golgi transport indicated by the accumulation of ER glycosylated forms in the BFA-treated cells (Figure 6; Graham et al., 1993). These results further support the conclusion that α1,6-mannose and α1,2-mannose are added to pro-αf in separate Golgi compartments.

Figure 6.

BFA-treated cells accumulate core glycosylated and α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf. BFA-sensitive cells (ise1) were pretreated for 10 min at 20°C with or without 75 μg/ml BFA, labeled for 7 min, and chased for 30 min. Pro-αf was recovered from each sample by immunoprecipitation and subjected to a second immunoprecipitation with αf- or α1,6-linkage serum. The α1,6 immunoprecipitates were incubated with or without endoM before electrophoresis in a 15% polyacrylamide gel. Pro-αf was also recovered from labeled mnn1 mnn2 cells for a positive control for the endoM treatment. unglyc, unglycosylated pro-αf; mαf, mature αf. (B) Quantitation of the data shown in lanes 7–10 of A. In this experiment, a small amount of the core glycosylated pro-αf contaminated the α1,6 immunoprecipitations (lanes 4 and 7) and was subtracted as background from the BFA-treated samples shown in B.

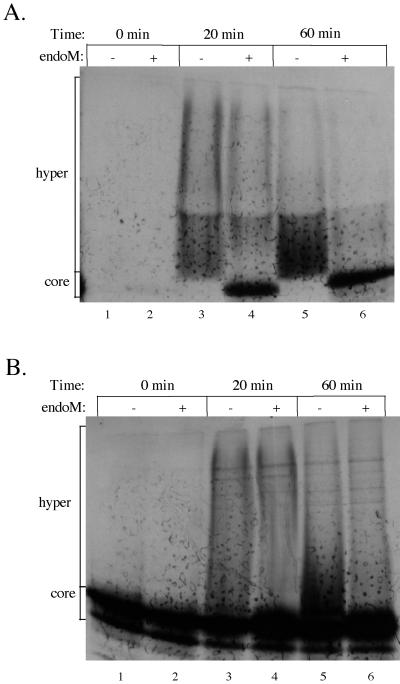

Transport of pro-αf from the ER to the Golgi In Vitro Results in a Mixture of α1,6- and α1,2-Mannosylated Forms

Transport of pro-αf from the ER to the Golgi can be reconstituted in permeablized yeast cells using the modification of pro-αf with α1,6-mannose to score the fusion of ER-derived transport vesicles (COPII coated) with Golgi acceptor membranes (Barlowe et al., 1994). We wished to test whether pro-αf transported to the Golgi in vitro would also receive α1,2-mannose, perhaps indicating reconstitution of an intra-Golgi transport step. Franzusoff and Schekman (1989) had previously reported that a portion of α1,6-mannosylated pro-αf produced in vitro was resistant to endoM digestion. To further address the kinetics of these modification events in vitro, transport reactions were performed at 23°C with wild-type semi-intact cells incubated with cytosol, ATP, and in vitro–translated 35S-labeled prepro-αf as previously described (Barlowe et al., 1994). Samples were harvested at 0, 20, and 60 min of incubation and solubilized with SDS to terminate the reaction. Each sample was immunoprecipitated with α1,6-linkage-specific antiserum to analyze only the Golgi-modified pro-αf (Figure 7A) or precipitated with the lectin conconavalin A to bring down all glycosylated forms (Figure 7B). Samples were split evenly and treated with endoM or left untreated. We found that pro-αf in the 0-min incubation had received core oligosaccharides in the ER and could be precipitated with conconavalin A but had not been subjected to Golgi mannosylation. At the next time point examined (20 min), >50% of the Golgi-modified pro-αf was sensitive to endoM digestion (Figure 7A). Therefore, as predicted from the in vivo experiments, most of the pro-αf was transported to a compartment that contained only the α1,6-mannosyltransferase activity.

Figure 7.

ER to Golgi transport assay results in both α1,6-mannosylated and α1,2-mannosylated forms of pro-αf. Semi-intact yeast cells were incubated with cytosol, 35S-labeled prepro-αf, and ATP for the times indicated. Samples from each time point were removed and immunoprecipitated with either α1,6-linkage serum (A) or concanavalin A-Sepharose (B), split evenly, and treated with or without endoM.

The percentage of α1,2-mannosylated pro-αf (endoM resistant) produced in vitro did not change significantly between the 20- and 60-min time points, even though the total amount of Golgi-modified pro-αf increased. If two transport steps were being reconstituted, we would have expected the α1,6 form to disappear with a concomitant increase in the α1,2 form. This was not the case, which suggests that there were two populations of Golgi acceptor membranes present in vitro. One population would contain only the α1,6-mannosyltransferase, whereas the second would contain both α1,6- and α1,2-mannosyltransferases, but other interpretations are also possible, and so the mechanism for producing the α1,2-modified pro-αf form in vitro is not clear. However, the primary conclusion of this experiment is that we detected a Golgi acceptor compartment that contained only the α1,6-mannosyltransferase activity.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have described a method to quantitate the major N-glycan biosynthetic intermediates on pro-αf using linkage-specific antisera and endoM. We have found that α1,6-mannose, α1,2-mannose, and α1,3-mannose are added sequentially to pro-αf in a temporally ordered manner. Based on the results described here and in a previous report (Graham and Emr, 1991), the intercompartmental protein transport factor Sec18/NSF is required at each step of the following pathway in pro-αf biosynthesis and secretion: core glycosylation → α1,6-mannosylation → α1,2-mannosylation → α1,3-mannosylation → Kex2 processing → exocytosis of mature αf.

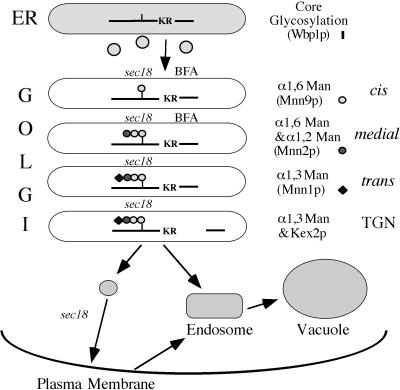

The SEC18 requirement strongly implies that a membrane fusion event is required at each step to bring together pro-αf with the modifying enzyme. This further suggests that each modification event (beyond the core glycosylation event) is catalyzed within a distinct compartment of the Golgi complex. A model describing the compartmental organization of the yeast Golgi complex based on the current work and earlier publications is presented in Figure 8. In this model, Golgi compartments are defined functionally by the initial site of pro-αf modification. However, it is possible that a specific mannosyltransferase also acts in compartments distal to the first one assigned in this model, an activity that would not be detected in our experiments. In fact, a significant portion of α1,3-mannosyltransferase (Mnn1p) appears to be localized to the same compartment as Kex2p (Graham and Krasnov, 1995). Mnn1p appears to cycle between the trans and TGN compartments, and interestingly, a MAP kinase signal transduction cascade regulates the distribution of Mnn1p between these two Golgi compartments (Reynolds et al., 1998). Therefore, this model is not meant to represent a static localization of the modifying enzymes.

Figure 8.

Compartmental organization of the yeast Golgi complex. (see DISCUSSION for explanation).

Likewise, it is possible that some of the α1,6-mannosyltransferase is also localized to the α1,2-mannosyltransferase compartment (medial-Golgi). There are two distinct multiprotein complexes that contain Mnn9p and exhibit α1,6-mannosyltransferase activity that have been isolated in immune complexes from yeast (Jungmann and Munro, 1998). Both complexes appear to exhibit some α1,2-mannosyltransferase activity in vitro, although neither complex contains the Mnn2 or Mnn5 α1,2-mannosyltransferases needed to branch the α1,6-mannan chain (Rayner and Munro, 1998). By immunofluorescence microscopy, Raynor and Munro (1998) examined the distribution of an epitope-tagged Mnn2p with Anp1p, a component of an α1,6-mannosyltransferase complex, and found significant colocalization but with some cisternae staining for only one or the other protein. In contrast, Mnn2p (an α1,2-mannosyltransferase) and Mnn1p (an α1,3-mannosyltransferase) showed little colocalization (Rayner and Munro, 1998). These observations are represented in the model shown in Figure 8 and could provide an explanation for the endoM-resistant fraction of pro-αf produced in the in vitro ER to Golgi transport assay. It is possible that some of the ER-derived transport vesicles fused directly to a medial compartment containing both α1,6- and α1,2-mannosyltransferases.

It is also possible that there are more than four compartments that make up the yeast Golgi complex. For example, Gaynor et al. (1994) had suggested that the initiating α1,6-mannosyltransferase (Och1p) is contained in a cis-Golgi compartment that is distinct from the compartment containing the elongating α1,6-manosyltransferase. This was based on the observation that a fusion protein containing an ER retrieval signal (KKXX) received only the initiating α1,6 mannose as it cycled through the early Golgi (Gaynor et al., 1994). However, we cannot distinguish between these two pro-αf intermediate forms in our experiments, and so we have been unable to show a Sec18-dependence for conversion of the Och1p-modified form to the elongated α1,6 outer chain form. Thus, we are only presenting the Sec18-dependents steps in our model, even though other compartments are likely to exist. In fact, it has been estimated that there are nearly 30 Golgi cisternae per yeast cell (Preuss et al., 1992). Although it seems unlikely that each cisterna has a unique function, there are certainly enough cisternae present in the cell to accommodate more compartments than presented in Figure 8.

The fundamental mechanism of protein transport through the Golgi complex has been a center of controversy in recent years. Two models have been proposed that differ in respect to whether the cargo proteins alone or the entire Golgi cisternae move through the secretory pathway. The vesicular transport–stationary cisterna model suggests that Golgi cisternae are relatively stable compartments of the secretory pathway and that proteins destined for secretion are moved from one compartment to the next in transport vesicles (Farquhar and Palade, 1981). The cisternal maturation model suggests that the cis-Golgi cisterna is formed de novo by fusion of ER-derived anterograde transport vesicles with each other and with retrograde vesicles carrying cis-Golgi enzymes. The cis-Golgi then matures into a medial-Golgi compartment by shedding cis-Golgi enzymes into retrograde vesicles and fusing with retrograde vesicles carrying medial-Golgi enzymes. This process continues until, ultimately, the TGN breaks down completely into vesicles targeted to the plasma membrane, the endosomal–lysosomal system, or earlier Golgi compartments.

Our data could be consistant with either of these models. For example, it is possible that pro-αf is packaged into anterograde vesicles at each step of the secretory pathway, and the fusion of these vesicles with the next compartment is blocked in the sec18 mutant at the nonpermissive temperature. This must be the case for transport of mature αf from the TGN to the plasma membrane, although the other steps are less certain and could also be explained by a cisternal maturation model (Pelham, 1998). In this case, fusion of retrograde vesicles carrying Golgi-modifying enzymes with an earlier compartment containing pro-αf could be blocked in the sec18 mutant at the nonpermissive temperature. For example, the α1,2-mannosylated pro-αf form would not mature to the α1,3-mannosylated form in the sec18 mutant, because retrograde vesicles carrying α1,3-mannosyltransferase could not fuse with the membranes containing pro-αf. With this interpretation, the Golgi compartments depicted in Figure 8 would represent stages in maturation rather than stable compartments. Therefore, our model describing the compartmental organization of the yeast Golgi complex and the data that contributed to this model are consistent with both proposed mechanisms for protein transport through the Golgi complex. Methods for cleanly separating Golgi cisternae from transport vesicles will have to be developed to test these models in the yeast system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alex Franzusoff for providing TH2-10D and Bob Fuller for the KEX2 disruption plasmids. We thank Tom Oeltmann for help with the colorimetric assay methods and Jeff Flick for suggesting a partial purification of the yeast mannan substrate. Finally, we thank all of the members of the Graham laboratory for their support and encouragement during the course of these experiments. This work was supported by grant GM-50409 from the National Institutes of Health (to T.R.G.).

REFERENCES

- Baker D, Hicke L, Rexach M, Schleyer M, Schekman R. Reconstitution of SEC gene product-dependent intercompartmental protein transport. Cell. 1988;54:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C, Orci L, Yeung T, Hosobuchi M, Hamamoto S, Salama N, Rexach MF, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Schekman R. COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1994;77:895–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan A, Brenner C, Fuller RS. Quantitative assessment of enzyme specificity in vivo: P2 recognition by Kex2 protease defined in a genetic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10384–10389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey H. Proteases and the processing of precursors to secreted proteins in yeast. Yeast. 1988;4:17–26. doi: 10.1002/yea.320040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetic method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Esmon B, Novick P, Schekman R. Compartmentalized assembly of oligosaccharides on exported glycoproteins in yeast. Cell. 1981;25:451–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar MG, Palade GE. The Golgi apparatus (complex)—(1954–1981)—from artifact to center stage. J Cell Biol. 1981;81:77s–103s. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.77s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar MG, Palade GE. The Golgi apparatus: 100 years of progress and controversy. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:2–10. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01187-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzusoff A, Schekman R. Functional compartments of the yeast Golgi apparatus are defined by the sec7 mutation. EMBO J. 1989;8:2695–2702. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RS, Sterne RE, Thorner J. Enzymes required for yeast prohormone processing. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:345–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor EC, te Heesen S, Graham TR, Aebi M, Emr SD. Signal-mediated retrieval of a membrane protein from the Golgi to the ER in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:653–665. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TR, Emr SD. Compartmental organization of Golgi-specific protein modification and vacuolar protein sorting events defined in a sec18(NSF) mutant. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:207–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TR, Krasnov VA. Sorting of yeast α-1,3-mannosyltransferase is mediated by a lumenal domain interaction, and a transmembrane domain signal that can confer clathrin-dependent Golgi localization to a secreted protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:809–824. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TR, Scott P, Emr SD. Brefeldin A reversibly blocks early but not late protein transport steps in the yeast secretory pathway. EMBO J. 1993;12:869–877. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TR, Seeger M, Payne GS, MacKay V, Emr SD. Clathrin-dependent localization of α1,3 mannosyltransferase to the Golgi complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:667–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herscovics A, Orlean P. Glycoprotein synthesis in yeast. FASEB J. 1993;7:540–550. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.6.8472892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann J, Munro S. Multi-protein complexes in the cis Golgi of saccharomyces cerevisiae with alpha-1,6-mannosyltransferase activity. EMBO J. 1998;17:423–434. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–664. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, Wickner W, Haas A. Sec18p (NSF)-driven release of Sec17p (alpha-SNAP) can precede docking and fusion of yeast vacuoles. Cell. 1996;85:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I, Simons K. The Golgi complex. in vitro veritas? Cell. 1992;68:829–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90027-A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer HH, Morre DJ. Perspectives on Golgi apparatus form and function. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1991;17:2–14. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Ballou C. Structure of the linkage region between the polysaccharide and protein parts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7685–7694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Maitra SK, Ballou CE. An endo-α1,6-d-mannanase from a soil bacterium. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Nagasu T, Shimma Y, Kuromitsu J, Jigami Y. OCH1 encodes a novel membrane bound mannosyltransferase: outer chain elongation of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. EMBO J. 1992;11:2511–2519. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson T, Pypaert M, Hoe MH, Slusarewicz P, Berger EG, Warren G. Overlapping distribution of two glycosyltransferases in the Golgi apparatus of HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:5–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham HR. Getting through the Golgi complex. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyroche A, Antonny B, Robineau S, Acker J, Cherfils J, Jackson CL. Brefeldin A acts to stabilize an abortive ARF-GDP-Sec7 domain protein complex: involvement of specific residues of the Sec7 domain. Mol Cell. 1999;3:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss D, Mulholland J, Franzusoff A, Segev N, Botstein D. Characterization of the Saccharomyces Golgi complex through the cell cycle by immunoelectron microscopy. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:789–803. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer NK, Westehube LJ, Schekman R. Vesicle-mediated protein sorting. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:471–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke WC, Kern KA, Antalis C, Ballou CE. Genetic control of yeast mannan structure. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4660–4666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner JC, Munro S. Identification of the MNN2 and MNN5 mannosyltransferases required for forming and extending the mannose branches of the outer chain mannans of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26836–26843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding K, Brickner JH, Marschall LG, Nichols JW, Fuller RS. Allele-specific suppression of a defective trans-Golgi network (TGN) localization signal in Kex2p identifies three genes involved in localization of TGN transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6208–6217. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds TB, Hopkins BD, Lyons MR, Graham TR. The high osmolarity glycerol response (HOG) MAP kinase pathway controls localization of a yeast Golgi glycosyltransferase. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:935–946. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Klionsky DJ, Banta LM, Emr SD. Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4936–4948. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JS, Taatjes DJ, Lucocq JM, Weinstein J, Paulson JC. Demonstration of an extensive trans-tubular network continuous with the Golgi apparatus stack that may function in glycosylation. Cell. 1985;43:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman JE, Wieland FT. Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science. 1996;272:227–234. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Fink GR, Lawrence LW. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sollner T, Bennett MK, Whiteheart SW, Scheller RH, Rothman JE. A protein assembly-disassembly pathway in vitro that may correspond to sequential steps of synaptic vesicle docking, activation, and fusion. Cell. 1993a;75:409–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner T, Whiteheart SW, Brunner M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Geromanos S, Tempst P, Rothman JE. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature. 1993b;362:318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro RG. Analysis of sugars found in glycoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1966;8:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Factors controlling the glycosylation potential of the Golgi apparatus. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:34–40. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco A, Hendricks L, Moremen KW, Tulsiani DR, Touster O, Farquhar MG. Cell type-dependent variations in the subcellular distribution of alpha-mannosidase I and II. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:39–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidman PJ, Melancon P, Block MR, Rothman JE. Binding of an N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein to Golgi membranes requires both a soluble protein(s) and an integral membrane receptor. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1589–1596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickerham LJ. A critical evaluation of the nitrogen assimilation tests commonly used in the classification of yeasts. J Bacteriol. 1946;52:293–301. doi: 10.1128/JB.52.3.293-301.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]