Abstract

Individuals with Parkinson’s disease often exhibit symptoms of social anxiety. However, they rarely meet criteria for social phobia due to the medical exclusion criteria of DSM-IV. The present study reports the case of a 60-year-old male with Parkinson’s disease who also met criteria for social phobia. After receiving 12 weekly cognitive-behavioral group sessions for social phobia, clinician ratings and self-report measures at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up showed a significant short-term and long-term reduction of his social anxiety. These findings suggest that cognitive-behavior therapy may be an effective treatment for social anxiety, even if these symptoms are related to Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: medical condition, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive-behavior therapy, social phobia

Cognitive-behavioral treatment for social phobia in Parkinson’s disease: A single-case study

Individuals with Parkinson’s disease frequently experience symptoms of anxiety, and a particularly high association has emerged between Parkinson’s disease and social phobia. One study reported that of 24 Parkinson’s patients evaluated, 9 (38%) suffered from clinically significant social anxiety symptoms (Stein, Heuser, Juncos & Uhde, 1990). However, half of these individuals were not assigned a diagnosis of social phobia because their anxiety was judged to be secondary to their self-consciousness and embarrassment about their parkinsonian symptoms being visible to others (Stein et al., 1990). The DSM-IV specifies that if a medical condition is present, a diagnosis of social phobia is assigned only when the social fear is unrelated to a medical condition. Lauterbach and Duvoisin (1991) hypothesized that idiopathic Parkinsonism, the type of Parkinsonism for which there is no known cause, may be more closely related to social phobia than familial Parkinsonism, which has been identified as an inherited condition. Furthermore, idiopathic Parkinsonism seems to be more restricted to a dopaminergic deficit in the brain (Agid, Javoy-Agid & Ruberg, 1987; Stein et al., 1990). Similarly, a recent single photon emission computed tomography study in patients with social phobia found that striatal dopamine reuptake site densities were lower in patients with social phobia than in individuals without a mental disorder (Tiihonen et al., 1997).

It is unclear if the dopaminergic dysfunction underlying social phobia and Parkinson’s disease is to be understood as a biological link between both conditions. Too little is known about the neurobiology of social phobia, and evidence for a common dysfunction remains equivocal. However, in a sample of individuals with social phobia, Tiihonen et al. (1997) identified a dopaminergic dysfunction in the striatum, which also has been found to have the lowest levels of dopamine in Parkinson’s disease. Some researchers have suggested that the dopamine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease could lead to changes in the noradrenergic system, which in turn are associated with the development of anxiety disorders (e.g., Richard, Schiffer, & Kurlan, 1996). Further evidence that dopaminergic dysfunction may be the biological link between these conditions comes from pharmacological studies suggesting that monoaminooxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are among the most effective drugs in social phobia, while tricyclic antidepressants have not been found effective for this condition (for a review see Blanco, Schneier & Liebowitz, 2001).

In animal research, studies have found that dopamine receptor binding and density are associated with social status in monkeys (Grant et al., 1998), indicating a potential association between dopamine and ease or comfort in social interactions. On the other hand, individuals with social phobia did not respond differently than normal controls to levodopa, which is one of the most effective drugs used to treat Parkinson’s disease, in a neuroendocrine challenge (Tancer et al., 1994/1995). In addition, MAOIs are not helpful in treating Parkinson’s disease. Although each condition seems to respond to different drugs, Stein (1998) has suggested that the high rates of social phobia in Parkinson’s disease may be accounted for by abnormalities in the dopaminergic system. There seems to be compelling preliminary evidence for a biological link between these disorders, but this evidence does not discount the hypothesis that social anxiety in individuals with Parkinson’s may be conceptualized as a psychological reaction to a medical condition.

There also exist a number of effective psychological interventions for social phobia (e.g., Cohn & Hope, 2001). Of those interventions, cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) seems to be the most effective strategy. However, this type of intervention has only been examined in settings where individuals have been screened out for complicating problems, such as Parkinson’s disease. The present study is the first to explore the effects of CBT for social phobia in a patient with Parkinson’s disease.

Method

Diagnostic Information

John is a 60-year-old married man with three grown children. He presented at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University requesting treatment for his social anxiety. The diagnostic intake consisted of a semi-structured clinical interview, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L, Di Nardo, Brown & Barlow, 1994). In this interview, John stated that he had been anxious in social situations since first grade. He further reported, however, that his social anxiety influenced only one major life decision in the past (i.e., not attending college) and that he was never really bothered by his anxiety until about 5 years prior to the interview when he began to experience severe physical distress (e.g., sweating, heart palpitations, and shaking) in an increasing number of social situations, including being at parties, eating in public, speaking in front of other people, and speaking with unfamiliar people, particularly over the phone. John reported his social fears centered on others noticing his Parkinson tremor that resembles anxiety, “looking foolish”, or “saying the wrong thing” in a social situation, and he feared that others would not like him. Several of his social concerns clearly referred to physical symptoms caused by the Parkinson’s disease (e.g., trembling, gait difficulties). However, he also expressed concerns that seem unrelated to his neurological disorder (e.g., how his voice sounded on the phone and how he came across to others). In addition, he avoided any anticipated confrontation with others, such as speaking with “pushy” salespeople. As a result of this fear, he refused to answer the telephone and rarely returned calls when somebody left a message on the answering machine. After the onset of his social phobia, John began to experience feelings of depression, and at the diagnostic intake interview it was found that John had a past episode of major depression, which occurred just prior to the emergence of his Parkinson’s symptoms. John was diagnosed with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease less than a year after he began to experience significant distress and interference due to his social phobia. Following this, he took a leave from his job and retired permanently one year later. He reported that his social anxiety has progressively worsened since then. He also reported that he feels that his tremor gets worse when he anticipates a social interaction. John exhibited a strong tremor in both arms during the diagnostic interview and throughout treatment. At the time of the assessment, he was taking a variety of medications for Parkinson’s disease (Pramipexole: 3 mg, Amantadine: 200 mg), for sleeping difficulties (Trazodone: 100mg) and for his anxiety (Clonazepam: 1.5 mg). John was also taking an anticonvulsant (Gabapentin: 400 mg). He was stabilized on these medications and dosages throughout treatment, including his post-treatment assessment. At the 6-month follow-up assessment, he stated that he stopped taking Amantadine three months earlier, which was replaced by a mixed agent medication that consists of carbidopa and levodopa (25–100 mg, 3 times a day).

Based on John’s report, it was difficult to determine whether social phobia was a primary or secondary disorder in relation to his Parkinson’s disease. When John sought treatment, he had suffered from both disorders for approximately five years. He stated during the interview that while his symptoms of social anxiety had predated the onset of Parkinson’s disease by several decades, he was not bothered by these symptoms until 1994, just before he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. While John chose not to attend college and was anxious around public speaking, conversing with unfamiliar people, and dating situations, he felt he was not limited or distressed by his anxiety at that time.

It was concluded that John probably suffered from a sub-clinical social anxiety disorder prior to the onset of Parkinson’s disease, and the anxiety most likely met the threshold for a clinical disorder once he began to experience the physical sequellae of Parkinson’s disease. According to John’s retrospective report, his Parkinson’s disease lead to a dramatic exacerbation of his social anxiety, starting with fears that others might notice his tremor and rapidly generalizing to other physical symptoms, such as his gait. Parkinson’s disease might have been a predisposing factor in the development of his social phobia, and it remains unclear if, in the absence of the neurological disorder, John would have continued to function with a sub-clinical level of social phobia. John reported that his social anxiety intensified several months prior to receiving an official diagnosis of Parkinson’s, but he was already experiencing Parkinson’s symptoms at this point.

Treatment

Treatment consisted of 12 weekly group sessions of a cognitive-behavioral group program (Hofmann, 1999). The specific treatment protocol was Self-focused Exposure Therapy (SFET), which was developed as part of a treatment study to examine mediators and moderators of treatment change (Hofmann, 2000a). The components of the intervention include repeated in vivo exposure in session, video feedback, didactic training, and mirror exposure. A recent study demonstrated that SFET led to a large reduction in the social phobia subscale scores (Cohen, 1992) of the SPAI (effect size: 0.81) in a sample of social phobic individuals (Hofmann, 2000b). Furthermore, the results of two recent meta-analyses (Feske & Chambless, 1995; Gould et al., 1997) suggested that the efficacy of an earlier version of this protocol (Hofmann et al., 1995; Newman et al., 1994) produced effect sizes that were comparable to those of other empirically-supported interventions.

The group was conducted by two therapists (EH and NH) in 12 weekly 2-hour sessions with a group of 5 patients. John participated in 11 sessions. He missed the third session due to a family vacation he had planned prior to treatment.

Assessment of Treatment Efficacy

In order to determine the effects of treatment on John’s social anxiety, he underwent behavioral tests and questionnaires before and after treatment, and at six months follow-up. Furthermore, an abbreviated version of the ADIS-IV (mini-ADIS-IV) was conducted at posttreatment and at 6-month follow-up assessment. John had a very difficult time completing the questionnaire battery in a reasonable time due to his tremor. For take home packages this was less of an issue than for individual questionnaires that had to be completed on site prior to session. To facilitate the completion of the questionnaires, John dictated his ratings to one of the therapists.

Behavioral tests were designed to measure the generality of his social anxiety. The tasks of the test included (a) presenting a brief speech to an audience of two people (b) initiating and maintaining a conversation with a person of the opposite sex and (c) solving simple mathematical problems on a chalk board in front of two people. Each of these situations represents different social phobia domains (formal speaking, informal speaking, and observations by others) as described by Holt, Heimberg and Hope (1992). Before each task there was a 3-minute preparation period, and after each task there was a 3-minute recovery period. Each behavioral task was designed to take 10 minutes. After each preparation and baseline period, John was asked to complete the State subscale of the State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S, Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) and to rate his anxiety on a 9-point Likert type Subjective Unit of Distress (SUDS) scale. Furthermore, he was asked to complete the Focus of Attention Questionnaire (Chambless & Glass, 1984) after each behavioral task. In addition to these ratings, a clinician conducted the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS, Liebowitz, 1987) before the behavioral assessment.

Within one week before the behavioral assessment, John also completed a set of questionnaires including the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI, Turner, Beidel, Dancu & Stanley, 1989), the Fear Questionnaire (FQ, Marks & Mathews, 1979), the Self-Statements during Public Speaking Scale (SSPS, Hofmann & DiBartolo, 2000), the Trait-Subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T, Spielberger et al., 1983), the Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker (PRCS, Gilkonson, 1942; Paul, 1966), the Anxiety Control Questionnaire (Rapee, Craske, Brown & Barlow, 1996) and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Liebowitz, 1987), which was used as a self-report measure. It has been demonstrated that a self-report measure of this scale shows satisfactory psychometric characteristics (Fresco et al., in press).

In order to study changes in his social anxiety during treatment, John was asked to complete a self-report version of the LSAS after each session. In addition, he completed the Self-Statements during Public Speaking Questionnaire (Hofmann & DiBartolo, 2000) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) on a weekly basis.

Treatment response

Turner, Beidel and Wolff (1994) developed the Index of Social Phobia Improvement (ISPI) in an effort to capture the full range of psychopathology characterizing social phobia using individual measures reflecting a multimethod approach. Criteria for improvement were: (1) a decline of 20% or more in the SPAI difference score; (2) a decline of 2 points or more on the Fear Questionnaire presenting Symptom rating; (3) a decline of 2 points or more in the independent evaluators’ CGI-Severity rating; (4) an increase of 50% or more in the time spoken during the impromptu speech; and (5) a decline of 2 points or more in the task SUDS rating. Subjects receive one point for meeting the criterion on each individual measure of treatment improvement. A total score of 0 or 1 is considered no-to-minimal improvement, a score of 2–3 moderate improvement, and a score of 4–5 significant improvement. This index has demonstrated validity and is sensitive to treatment change (Turner et al., 1994).

Endstate status

The Social Phobia Endstate Functioning Index (SPEFI, Turner, Beidel, Long, Turner & Townsley, 1993) was used to determine the level of functioning at post-treatment assessment and follow-up. This composite index is comprised of 5 outcome measures including: (1) SPAI score of 59 or less; (2) FQ Presenting Symptom Rating of 2 or less; (3) CGI-Severity rating of 2 or less; (4) impromptu speech length of 5.7 min. or longer; and (5) a SUDS rating during the speech of 5 or less. Subjects receive one point for meeting each criterion. A total score of 0–1 indicates low, 2–3 indicates a moderate and 4–5 indicates a high endstate status.

Results

Table 1 presents John’s pre-treatment, post-treatment and 6-month follow-up treatment data based on the diagnostic assessments conducted by independent evaluators and self-report questionnaire data. All findings indicated a significant improvement in John’s level of social anxiety from pre- to posttreatment, which was maintained at the 6-month follow-up assessment. To determine the significance of changes in John’s social anxiety, confidence intervals (CI) for the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI; Turner et al., 1989) were calculated based on means and standard deviations from a reference sample of individuals with untreated social phobia (Hofmann & DiBartolo, 2000). Based on the CI’s, it was determined whether the John’s score fell within the 95% confidence interval of the reference group. These comparisons (the confidence intervals can be seen in the note of Table 1) indicate that John’s pretreatment score on the social phobia subscale fell within the 95% CI of an untreated reference population. His post-treatment scores fell outside of the 95% CI of the untreated reference sample. However, his follow-up score on this measure again fell inside the 95% CI, but outside of the 68% CI (see Table 1). It may be concluded that John’s social anxiety significantly improved during treatment and that he maintained some of the improvements he made for at least six months after treatment. The post-treatment assessment by an independent evaluator indicated that John no longer had a clinically significant diagnosis of social phobia. At posttreatment, there were still some sub-clinical social concerns, however, 6 months after treatment ended, these residual concerns were no longer found.

Table 1.

Data from questionnaires and clinician evaluations.

| Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview/Questionnaires | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | 6-month follow-up |

| ADIS-IV-L: | Clinical social phobia, generalized | Subclinical social phobia | No diagnosis |

| CSR: 5 | CSR: 2 | ||

| clinician rated: | |||

| LSAS – Fear | 36 | 15 | 18 |

| LSAS – Avoidance | 40 | 0 | 2 |

| John rated: | |||

| LSAS – Fear | 43 | 21 | 17 |

| LSAS – Avoidance | 34 | 0 | 5 |

| PRCS | 27 | 14 | 12 |

| ACQ-tot | 63 | 92 | 94 |

| SPAI-Social | 131 | 53 | 69 |

| SPAI-Agoraphobia | 25 | 9 | 10 |

| SPAI-total | 106 | 44 | 59 |

| FQ | 34 | 11 | 12 |

| SSPS-positive | 4 | 13 | 13 |

| SSPS-negative | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| BDI | 12 | 7 | not assessed |

| STAI-Trait | 56 | 41 | 42 |

Note. The table shows John’s diagnostic information and questionnaire data at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and the 6-month follow-up assessment. CSR: Clinical Severity Rating (0–8, with 4 being the threshold for a clinical diagnosis); LSAS: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Sale, Fear: Fear scale total score (0–72); Avoidance: Avoidance scale total score (0–72); PRCS: Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker (0–30); ACQ-tot: Anxiety Control Questionnaire, sum score (0–150); SPAI-social: Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory, social anxiety subscale (0–192), confidence interval (CI) for 68%: 113.3 +/− 23.3, CI for 95%: 113.3 +/− 45.7; SPAI-Agoraphobia: Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory, agoraphobia subscale (0–78), CI for 68%: 17.7 +/− 11.0, CI for 95%: 17.7 +/− 21.6; SPAI-total: Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory, total score (0–192), CI for 68%: 95.6 +/− 22.4, CI for 95%: 95.6 +/− 43.9; FQ: Fear Questionnaire (0–128); SSPS-positive: Self-Statements during Public Speaking, positive statements (0–25); SSPS-negative: Self-Statements during Public Speaking, negative statements (0–25); BDI: Beck Depression Inventory (0–63); STAI-Trait: Trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (20–80).

John’s Behavioral Assessment Test data indicated only mild discomfort at posttreatment and follow-up assessment, whereas he experienced significant discomfort and anxiety in all social tasks at pretreatment. The Focus of Attention questionnaire indicated that, overall, his attention was less self-focused at posttreatment and 6 month follow-up. Furthermore, it was more other-focused during the conversation task.

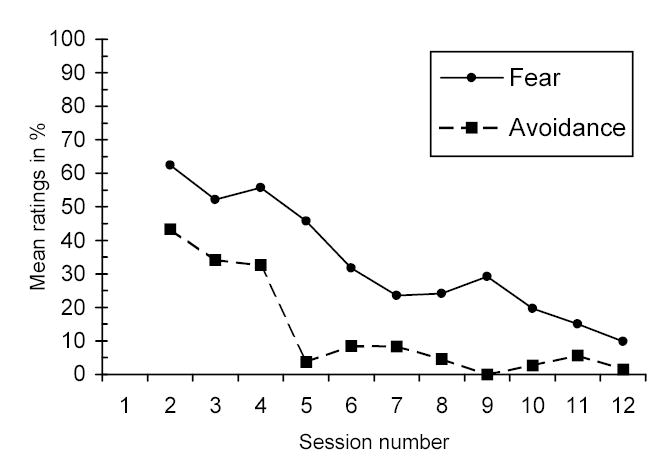

Figure 1 presents the session-by-session self-report ratings of John’s social phobia. These ratings suggest that John’s fear and avoidance in social situations declined markedly throughout the treatment.

Figure 1.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale – Mean fear and avoidance ratings as a function of time in treatment.

Treatment response

The Index of Social Phobia Improvement (ISPI) was 4, indicating significant improvement (Turner et al., 1994). The only area not accomplished was criterion #4, because John terminated the speech after approximately the same time lapse as he did during his pre-BAT. He stated that he was not anxious, but rather had nothing more to say. At the pre-BAT he stated the same reason for terminating, but he also indicated some anxiety.

Endstate status

The Social Phobia Endstate Functioning Index (SPEFI) at posttreatment was a score of “3,” indicating moderate endstate status. At follow-up, John received a score of 4, which indicates high endstate status. These data suggest that he maintained his treatment gains after treatment had terminated.

Discussion

Recent research suggests that anxiety disorders are relatively common in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The diagnosis of social phobia is particularly prevalent in this population (Stein et al., 1990). We have presented here a case study examining the outcome of a CBT program for social phobia conducted with an individual with Parkinson’s disease. The results indicate marked improvement on a variety of measures of social anxiety, including clinician ratings, self-report instruments and behavioral measures. Independent evaluators rated John’s social anxiety as significantly improved after treatment and at 6-month follow-up. John also reported considerably less anxiety in social situations after treatment as measured by questionnaires. Furthermore, he reported considerably lower anxiety during structured social situations at posttreatment. These treatment gains were maintained at the 6-month follow-up assessment.

Richard et al. (1996) reviewed the relationship between anxiety and Parkinson’s disease and they concluded that anxiety “can also develop prior to the motor features…” suggesting “that anxiety may not represent psychological and social difficulties in adapting to the illness, but rather may be linked to the specific neurobiological processes occurring in PD” (p. 390). Interestingly, Lauterbach and Duvoisin (1991) reported that 12 of their Parkinson patients diagnosed with social phobia experienced social anxiety symptoms prior to the diagnosis of the movement disorder. Similarly, Stein et al. (1990) stated that all four of their Parkinson’s patients diagnosed with social phobia were self-conscious about social situations and anxiety symptoms that were unrelated to their Parkinson’s symptoms. Richard et al. (1996) concluded that “it is still unclear whether anxiety is an emotional reaction to motor impairment, whether anxiety might worsen motor function, or whether anxiety and motor dysfunction occur together as the result of common, central neurochemical mechanisms” (p. 390).

If social phobia in Parkinson’s disease is indeed primarily the result of abnormalities in the dopaminergic system (Agid et al., 1987; Lauterbach & Duvoisin, 1991; Stein, 1998; Stein et al., 1990), CBT may be of limited therapeutic value. However, our findings suggest that CBT resulted in positive treatment outcome and maintenance of treatment gains for social phobia in a patient whose Parkinson’s disease seems closely connected with his social phobia. John’s social phobia onset around the same time that he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He reported that his social anxiety worsened after he received the diagnosis, and, prior to treatment, the trembling that occurred due to Parkinson’s often contributed to anxiety in social situations.

The historical association between these two conditions for John underscores the success of CBT at alleviating his social anxiety, in the absence of any obvious change in the status of his Parkinson’s disease. That is, his medication regimen did not change after successful CBT and his tremor did not seem to occur at a lesser intensity or frequency following treatment. However, as changes in tremor intensity or frequency may not always be visible, psychophysiological assessments of tremor severity before and after treatment would be a better objective indicator of possible changes in his Parkinson’s symptomology. John reported after treatment that he was unsure whether the intensity or frequency of his tremor truly changed or whether he was merely less disturbed by the tremor and therefore did not attend to it as often.

From a diagnostic standpoint, our findings indicate that social phobia can be treated despite a medical condition that induces or exacerbates symptoms related to social anxiety. Although treatment with John varied little from typical group CBT for social phobia, patients with uncomplicated social phobia rarely show visible physical symptoms, and their fear that others will detect signs of anxiety stems from a bias in self-perception. Exposure and the process of habituation typically reduce this bias by disrupting the vicious cycle of increased anxiety and increased physical symptoms characteristic of anxiety. Unlike uncomplicated social phobic individuals, John suffered from observable physical symptoms that would persist regardless of anxiety treatment. John’s atypical situation had interesting implications for exposure treatment. For example, it often was necessary to induce physical sensations of anxiety in other group members by having them perform physical activities, such as jumping jacks, prior to delivering a speech in order to raise their physiological sensations associated with their anxiety to extremely high levels. This step in the exposure process was irrelevant for John, however. Instead, he was instructed to face the audience with his arms hanging so that the others could observe his tremor, and he was not permitted to explain to the audience why he was shaking. Because his tendency to hold his arms behind his back and always explain that he suffers from Parkinson’s disease to excuse his shaking had been identified as safety behaviors, group exposure exercises enabled John to engage in anxiety-provoking situations without relying on safety behaviors.

John’s catastrophic thoughts were similar to those reported by uncomplicated social phobics, such as fearing that others will judge him negatively because they will interpret his physical symptoms as signs of anxiety. Unlike “normal” social phobics, however, John could not expect that his shaking would disappear as his anxiety decreased over time. Rather, he expected that his tremor was likely to increase as his Parkinson’s progressed. John’s dilemma actually presented an ideal illustration of the role of exposure, as the goal is not to reduce the physical symptoms, but rather to tolerate them and engage in the anxiety-provoking activity. This process then enables the patient to realize that others typically do not perceive the symptoms from the critical, negative perspective that patients often believe others will hold. Ultimately, John was able to acknowledge that others would like and respect him even though he often showed undesirable physical symptoms due to anxiety or his neurological condition, or both. It was challenging and productive to conceptualize John’s symptoms in the context of an exposure treatment. John seemed to respond well to the therapists’ attempts to tailor the exposure exercises around his concerns regarding his physical symptoms. Based on his positive response to CBT, it appears that this treatment can provide significant help to patients with medical conditions by focusing on the patient’s thoughts and behaviors related to his or her medical symptomology.

The diagnosis of social phobia in patients with Parkinson’s disease can be easily overlooked because the patient’s apprehension in social situations might be interpreted as distress over their Parkinson’s symptoms. This might lead physicians to prescribe an increase in dosage of their medications for Parkinson’s, not addressing the underlying social anxiety. Cognitive-behavioral treatment can be effective in reducing the distress and interference associated with the social repercussions of his Parkinson’s disease even without specifically treating the physical symptoms of this medical problem that might be related to it. This further questions the validity of criterion H of the DSM-IV, which can rule out the diagnosis of social phobia if the social anxiety is exclusively focused on the features of a physical illness (such as Parkinson’s disease).

The present study is limited by the methodological shortcomings of a single case study. However, we hope that this case report will stimulate further research on the efficacy and clinical utility of CBT for anxiety disorders in patients with other medical and psychiatric conditions. Important data would come from studies that specifically focus on the treatment of anxiety symptoms that did not reach the level of a clinical diagnosis due to the medical exclusion criteria. Furthermore, future studies should explore any biochemical or neuropsychological changes that may occur as a result of psychological interventions.

Footnotes

Supported by NIMH grant MH-57326 to Dr. Hofmann.

References

- Agid, Y., Javoy-Agid, F. & Ruberg, M. (1987). Biochemistry of neurotransmitters in Parkinson’s disease. In C. D. Marsden & Fahn, S., Movement disorders 2: Butterworths international medical reviews. Boston, MA: Butterworths.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Blanco, C., Schneier, F. R. & Liebowitz, M. R. (2001). Psychopharmacology. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), From Social Anxiety to Social Phobia: Multiple Perspectives (pp. 335–353). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Chambless, D. L. & Glass, C. R. (1984). The Focus of Attention Questionnaire. Unpublished questionnaire, The American University, Washington, DC.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, L. G. & Hope, D. A. (2001). Psychosocial treatments of social phobia: A treatments by dimensions review. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), From Social Anxiety to Social Phobia: Multiple Perspectives (pp. 354–378). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Di Nardo, P. A., Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Feske U, Chambless DL. Cognitive behavioral versus exposure only treatment for social phobia: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:695–720. [Google Scholar]

- Fresco, D. M., Coles, M. E, Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hami, S., Stein, M. B., & Goetz, D. (in press). The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: Comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gilkonson H. Social fears as reported by students in college speech classes. Speech Monographs. 1942;9:131–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Buckminster S, Pollack MH, Otto MW, Yap L. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1997;4:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg, R. G. & Juster, H. R. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral treatments: Literature review. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope & Schneier, F. R., Social Phobia. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (261–309). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hofmann SG. Treatment of social phobia: Potential mediators and moderators. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000a;7:3–16. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/7.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Self-focused attention before and after treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000b;38:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, S. G. (1999). Self-focused exposure treatment for social phobia. Unpublished treatment manual. Boston University, Boston, MA.

- Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM. The Self-Statements during public speaking Scale: Scale development and preliminary psychometric characteristics. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(00)80027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Newman MG, Becker E, Taylor CB, Roth WT. Social phobia with and without avoidant personality disorder: Preliminary behavior therapy outcome findings. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CS, Heimberg RG, Hope DA. Situational domains of social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach EC, Duvoisin RC. Anxiety disorders in familial Parkinsonism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social Phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Mathews AM. Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Hofmann SG, Trabert W, Roth WT, Taylor CB. Does behavioral treatment of social phobia lead to cognitive changes? Behavior Therapy. 1994;25:503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, G. L. (1966). Insight and desensitization in psychotherapy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rapee RM, Craske MG, Brown TB, Barlow DH. Measurement of perceived control over anxiety-related events. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Richard IH, Schiffer RB, Kurlan R. Anxiety and Parkinson’s disease. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1996;8:383–392. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R. E., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden.

- Stein MB. Neurobiological perspectives on social phobia: From affiliation to zoology. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Heuser IJ, Juncos JL, Uhde TW. Anxiety Disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:217–220. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancer ME, Mailman RB, Stein MB, Mason GA, Carson SW, Golden RN. Neuroendocrine responsivity to monoaminergic system probes in generalized social phobia. Anxiety. 19941995;1:216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen J, Kuikka J, Bergstroem K, Lepola U, Koponen H, Leinonen E. Dopamine reuptake site densities in patients with social phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:239–242. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV, Stanley MA. An empirically derived inventory to measure social fears and anxiety: The Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Long PJ, Turner MW, Townsley RM. A composite measure to determine the functional status of treated social phobics: The Social Phobia Endstate Functioning Index. Behavior Therapy. 1993;24:265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Wolff PL. A composite measure to determine improvement following treatment for social phobia: The index of social phobia improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;32:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]