Who gets thyrotoxicosis?

Thyrotoxicosis occurs in approximately 2% of women and 0.2% of men.w1 Thyrotoxicosis due to Graves' disease most commonly develops between the second and fourth decades of life, whereas the prevalence of toxic nodular goitre increases with age. Autoimmune forms of thyrotoxicosis are more prevalent among smokers.w2 w3 Toxic nodular goitre is most common in regions where dietary iodine is insufficient.

Methods

I searched Medline for English language papers with the topics “thyrotoxicosis”, “Graves' disease”, and “goitre”, searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews by using the keyword “thyroid”, and used a personal archive of references.

How do patients with thyrotoxicosis present?

Symptoms of overt thyrotoxicosis include heat intolerance, palpitations, anxiety, fatigue, weight loss, muscle weakness, and, in women, irregular menses. Clinical findings may include tremor, tachycardia, lid lag, and warm moist skin.1 Symptoms and signs of subclinical hyperthyroidism, if present, are usually vague and nonspecific.

What causes thyrotoxicosis?

To treat thyrotoxicosis appropriately, determining the cause is essential. The most common causes of thyrotoxicosis are discussed below; other causes are listed in the table.

Table 1.

Causes of thyrotoxicosis

| Underlying aetiology | Diagnostic features | |

|---|---|---|

|

Common causes |

||

| Graves' disease |

Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) binds to and stimulates the thyroid |

Increased thyroid radioactive iodine uptake with diffuse uptake on scan, positive thyroperoxidase antibodies; raised serum thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin; diffuse goitre; ophthalmopathy may be present |

| Toxic adenoma |

Monoclonal autonomously secreting benign thyroid tumour |

Normal to increased thyroid radioactive iodine uptake with all uptake in the nodule on scan; thyroperoxidase antibodies absent |

| Toxic multinodular goitre |

Multiple monoclonal autonomously secreting benign thyroid tumours |

Normal to increased thyroid radioactive iodine uptake with focal areas of increased and reduced uptake on scan; thyroperoxidase antibodies absent |

| Exogenous thyroid hormone (thyrotoxicosis factitia) |

Excess exogenous thyroid hormone |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake; low serum thyroperoxidase values |

| Painless postpartum lymphocytic thyroiditis |

Autoimmune lymphocytic infiltration of thyroid with release of stored thyroid hormone |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake; thyroperoxidase antibodies present; occurs within six months after pregnancy |

|

Less common causes |

||

| Painless sporadic thyroiditis |

Autoimmune lymphocytic infiltration of thyroid with release of stored thyroid hormone |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake; thyroperoxidase antibodies present |

| Subacute thyroiditis |

Thyroid inflammation with release of stored thyroid hormone; possibly viral |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake; low titre or absent thyroperoxidase antibodies |

| Iodine induced hyperthyroidism |

Excess iodine |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake |

| Drug induced thyrotoxicosis (lithium, interferon alfa) |

Induction of thyroid autoimmunity (Graves' disease) or inflammatory thyroiditis |

Thyroid radioactive iodine uptake elevated in Graves' disease or low to undetectable in thyroiditis |

| Amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis |

Iodine induced hyperthyroidism (type I) or inflammatory thyroiditis (type II) |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake |

|

Rare causes |

||

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) secreting pituitary adenoma |

Pituitary adenoma |

Raised serum thyroid stimulating hormone and α-subunit with raised peripheral serum thyroid hormones |

| Gestational thyrotoxicosis |

Stimulation of thyroid gland thyroid stimulating hormone receptors by human chorionic gonadotrophin |

Thyroid radioactive iodine uptake contraindicated in pregnancy. First trimester, often in setting of hyperemesis or multiple gestation |

| Molar pregnancy |

Stimulation of thyroid gland thyroid stimulating hormone receptors by human chorionic gonadotrophin |

Molar pregnancy |

| Struma ovarii |

Ovarian teratoma with differentiation primarily into thyroid cells |

Low to undetectable thyroid radioactive iodine uptake (raised uptake of radioactive iodine in pelvis) |

| Widely metastatic functional follicular thyroid carcinoma | Thyroid hormone production by large tumour masses | Differentiated thyroid carcinoma with bulky metastases; tumour radioactive iodine uptake visible on whole-body scan |

Graves' disease

Graves' disease is an autoimmune disorder in which thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) binds to and stimulates the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor on the thyroid cell membrane, resulting in excessive synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormone.2 Patients with Graves' disease usually have diffuse, nontender, symmetrical enlargement of the thyroid gland. Ophthalmopathy, consisting of protrusion of the eyes with periorbital soft tissue swelling and inflammation, and inflammatory changes in the extraocular muscles resulting in diplopia and muscle imbalance, is clinically evident in 30% of patients with Graves' disease.1

Toxic nodular goitre

Toxic adenomas are benign monoclonal thyroid tumours that secrete excess thyroid hormone autonomously. Thyrotoxicosis may develop in patients with a single autonomous thyroid nodule or in those with multiple autonomous nodules (toxic multinodular goitre, also known as Plummer's disease). Nodular autonomy typically progresses gradually, leading first to subclinical, and then to overt, hyperthyroidism.w4 Remission is rare. Physical examination shows a single thyroid nodule, usually at least 2.5 cm in size,w5 or a multinodular goitre. Ophthalmopathy and other stigmata of Graves' disease, including antithyroid antibodies, are absent.

Summary points

Classic symptoms of thyrotoxicosis include heat intolerance, palpitations, anxiety, fatigue, weight loss, irregular menses in women, and tremor

Serum values of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) are decreased in both overt and subclinical thyrotoxicosis, but serum values of peripheral thyroid hormone are increased only in overt disease

Thyrotoxicosis can have many causes; determining the cause is essential to formulate a treatment plan

A radioactive iodine uptake and scan should be performed when the cause of a patient's thyrotoxicosis cannot be definitively determined by history and physical examination

Treatment options for forms of overt hyperthyroidism with normal to elevated radioactive iodine uptake include antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine therapy, and thyroidectomy

Treatment options for thyroiditis (low radioactive iodine uptake) induced thyrotoxicosis include β blockers to relieve symptoms and glucocorticoids to relieve anterior neck pain, if present

Whether or not to treat subclinical thyrotoxicosis remains controversial

Thyroiditis

Thyroiditis may cause transient thyrotoxicosis, with a characteristic low or undetectable thyroid radioiodine uptake.3 Painless lymphocytic thyroiditis occurs in up to 10% of women after giving birth.4 This is an inflammatory autoimmune disorder in which lymphocytic infiltration results in thyroid destruction and leads to transient mild thyrotoxicosis as thyroid hormone stores are released from the damaged thyroid. As the gland becomes depleted of thyroid hormone, progression to hypothyroidism occurs. Thyroid function returns to normal within 12-18 months in 80% of patients.

Painful subacute thyroiditis, the most common cause of thyroid pain, is a self limiting inflammatory disorder of possible viral aetiology. Patients typically present acutely with fever and severe neck pain or swelling, or both. About half will describe symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. After several weeks of thyrotoxicosis, most patients will develop hypothyroidism, similar to postpartum thyroiditis. Thyroid function eventually returns to normal in almost all patients. The hallmark of the laboratory evaluation of painful subacute thyroiditis is a markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein.

Exogenous ingestion of thyroid hormone

Excess exogenous thyroid hormone is often associated with thyrotoxicosis. This may be iatrogenic, either intentional, when TSH suppressive doses of thyroid hormone are prescribed to suppress the growth of thyroid cancer or decrease the size, or unintentional, when overly vigorous treatment with thyroid hormone is prescribed for hypothyroidism. Thyrotoxicosis factitia may also result from patients' surreptitious use of thyroid hormones or from inadvertent ingestion. Serum thyroglobulin values are low to undetectable in thyrotoxicosis factitia but are raised in all other causes of thyrotoxicosis.w6

How is thyrotoxicosis diagnosed?

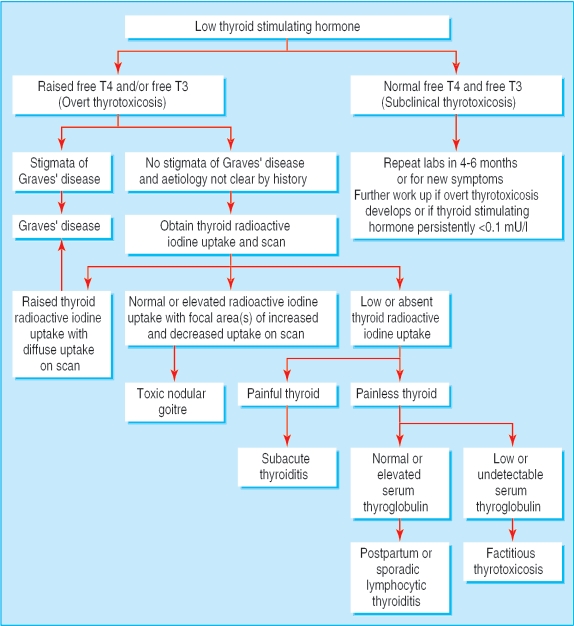

In all forms of overt thyrotoxicosis, the serum value of TSH is decreased and the measurements of free thyroxine (T4) or free thyroxine index or free tri-iodothyronine (T3), or both, are raised. Subclinical thyrotoxicosis is defined as the presence of a persistently low serum concentration of TSH, with normal free T3 and T4 concentrations. Once thyrotoxicosis has been identified by laboratory values, the thyroid radioiodine uptake and scan may be used to help distinguish the underlying aetiology (figure). Thyroid radioiodine uptake is raised in Graves' disease. It may be normal or raised in patients with a toxic multinodular goitre. It is very low or undetectable in thyrotoxicosis resulting from exogenous administration of thyroid hormone or from the thyrotoxic phase of thyroiditis. A scan may be helpful in differentiating between Graves' disease (diffuse uptake) and toxic multinodular goitre (focal areas of increased uptake).w7 The presence of raised serum concentrations of thyroperoxidase (TPO) antibodies indicates an autoimmune thyroid disorder and a raised TSI value indicates Graves' disease.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of a low serum value of thyroid stimulating hormone

How should overt thyrotoxicosis be treated?

Much of the treatment for thyrotoxicosis is based on empirical evidence; to date relatively few, large scale, randomised clinical trials have been conducted. Perhaps for this reason, treatment preferences vary substantially by region.

Antithyroid drugs

The thionamide drugs propylthiouracil (PTU) and methimazole are available in the United States (box 1, patient's story). Carbimazole, which is available in Europe and Asia, is similar to methimazole, to which it is metabolised.2 The thionamides all decrease thyroid hormone synthesis and will control hyperthyroidism within several weeks in 90% of patients.5 The thionamides may also decrease serum TSI concentrations in patients with Graves' disease.6 In addition, large doses of PTU, but not methimazole or carbimazole, decrease the peripheral conversion of T4 to the active hormone T3.5 A small, randomised clinical trial has determined that a major advantage of methimazole over PTU is the fact that it may be given once daily, whereas PTU requires multiple daily doses.7

Thionamides are used in patients with Graves' disease in the hope of inducing a remission. On the basis of the results of four randomised clinical trials variously comparing treatment durations of 6, 12, 18, 24, and 42 months, it has been determined that treatment with a thionamide for 12-18 months is optimal, resulting in long term remission in 40-60% of patients with Graves' disease.8 Aggregate data from several small clinical trials show no clear benefit from using a block-replace regimen (a large dose of a thionamide in combination with thyroid hormone).8 Because toxic nodular goitre rarely, if ever, goes into remission, thionamides may be used for the short term treatment of patients with toxic nodular goitre, to induce euthyroidism before definitive treatment, but are not appropriate for long term therapy. Thionamides are never appropriate for the treatment of patients with thyroiditis, in whom no excess synthesis of thyroid hormone occurs.

Box 1: Patient's story

I am a 65 year old African-American woman. In June 2005, I visited my primary care doctor, primarily because of swelling in my feet. I also felt very tired, had lost weight, and my hands were shaking. The doctor examined me and ordered several blood tests, including a thyroid test. Based on the results, she ordered a thyroid uptake and scan and referred me to an endocrinologist.

When I met the endocrinologist, my symptoms had worsened. I was extremely exhausted. It was difficult to walk or stand, and I was barely able to function. After examining me and reviewing the uptake and scan, my endocrinologist informed me that I had Graves' disease. She assured me that the disease is treatable, and prescribed methimazole and atenolol. That assurance, combined with the medicines she prescribed, helped me to feel better almost immediately. I continue to take the medicines as prescribed; I also meditate or relax daily.

My endocrinologist closely monitors my progress; she has reduced the methimazole and discontinued the atenolol. I feel great. She tells me that my thyroid is almost normal, and she will continue to monitor my progress for at least a year.

Roberta Owens-Jones

Minor side effects—such as fever, rash, urticaria, and arthralgias—occur in up to 5% of patients taking thionamides. More severe side effects are relatively rare. The side effects of methimazole and carbimazole, but not PTU, may be dose related.5 Agranulocytosis occurs in approximately 0.5% of patients treated with thionamides.9 Mild rises in transaminase concentrations occur in up to 30% of patients taking PTU,w8 but severe hepatotoxicity has been reported only rarely.w9 Patients taking methimazole or carbimazole may develop reversible cholestasis or, much more rarely, acute inflammatory hepatitis.10 Finally, vasculitis positive for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies has been reported as a rare complication of PTU use.11

Untreated hyperthyroidism during pregnancy increases the risk for fetal and maternal complications. Thionamides cross the placenta in small amounts and may cause fetal hypothyroidism and goitre.12 Limited evidence therefore shows that treatment with relatively low thionamide doses (just enough to keep the mother's free T4 index in the high-normal to slightly thyrotoxic range) is advisable.13 Methimazole has been associated with cutis aplasia and with other congenital anomalies—such as oesophageal and choanal atresia—in rare case reports.14 For this reason, PTU is preferred over methimazole or carbimazole during pregnancy in regions where it is available.5 Although small amounts of thionamide medications are secreted in breast milk, prospective clinical studies have shown that the use of up to 750 mg/day of PTU or up to 20 mg/day of methimazole in lactating mothers does not affect infants' thyroid function.15,16

Other drugs

In patients with severe hyperthyroidism or those with thyroiditis (in whom thionamides are inappropriate), adjunctive drugs may be used to alleviate symptoms or restore euthyroidism more rapidly. None of these therapies treat the underlying causes of thyrotoxicosis. β blockers relieve symptoms such as tachycardia, tremor, and anxiety in thyrotoxic patients. β blockade should be used as the primary treatment only in patients with thyrotoxicosis due to thyroiditis. High dose glucocorticoids may be used to inhibit conversion of T4 to T3 in patients with thyroid storm (the most severe form of thyrotoxicosis). Glucocorticoids may also be used to relieve severe anterior neck pain and to restore euthyroidism in patients with painful subacute thyroiditis. Inorganic iodide (SSKI or Lugol's solution) decreases the synthesis of thyroid hormone and release of hormone from the thyroid in the short term. It is used to treat patients with thyroid storm or, more commonly, to reduce thyroid vascularity before thyroidectomy. Iopanoic acid, an oral cholecystographic agent rich in iodine, decreases synthesis and release of thyroid hormone and inhibits the conversion of T4 to T3. Short term use of iopanoic acid is effective for the treatment of thyroid storm or for rapid preparation for thyroidectomy, but it is ineffective as long term therapy.w10

Radioactive iodine

Treatment with 131I is effective for patients with hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease or toxic nodular goitre: retrospective data show that 80-90% will become euthyroid within 8 weeks after a single 131I dose, whereas the remainder will require one or more additional doses.17 In patients with toxic multinodular goitre, a prospective clinical study has determined that radioactive iodine therapy will reduce goitre size by 40%.18 131I eventually causes permanent hypothyroidism in almost all patients.

Possible side effects of 131I therapy include mild anterior neck pain caused by radiation thyroiditis or worsened thyrotoxicosis for several days, owing to the leakage of preformed thyroid hormones from the damaged thyroid gland. Pretreatment with a thionamide may reduce the risk for worsened thyrotoxicosis after treatment with 131I. Retrospective studies have shown that the efficacy of treatment with 131I is decreased after PTU treatment,w11 but both prospective and retrospective studies have shown that the efficacy of 131I is not diminished after treatment with methimazole or carbimazole as long as the drug is discontinued three to five days before 131I is administered.w11 w12

Graves' ophthalmopathy may develop or worsen after treatment with 131I, especially in smokers and in patients with severe hyperthyroidism.19 Strong prospective evidence shows that the exacerbation of Graves' ophthalmopathy can be prevented by the simultaneous administration of glucocorticoids.20

Radioactive iodine therapy is relatively contraindicated in children and adolescents because of the lack of data regarding the long term risks associated with radiation. Radioactive iodine is absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation.

Thyroidectomy

A meta-analysis found that thyroidectomy cures hyperthyroidism in more than 90% of cases.21 In addition, it eliminates compressive symptoms from large toxic multinodular goitres. Unlike radioactive iodine treatment, it is not associated with worsening of Graves' ophthalmopathy. Thyroidectomy is safe in the second trimester of pregnancy. The procedure bears almost no risk of death when carried out by experienced surgeons. However, thyroidectomy is complicated by recurrent laryngeal nerve injury or permanent hypoparathyroidism in 1-2% of patients.1 Transient hypocalcaemia, bleeding, or infection are also potential complications. Surgery results in permanent hypothyroidism in most patients.

Thionamides are used to restore euthyroidism before thyroidectomy to avoid more severe thyrotoxicosis from leakage of thyroid hormone into the circulation at the time of surgery and to reduce operative and postoperative complications associated with anaesthesia and surgery in thyrotoxic patients. SSKI or Lugol's solution is given for seven to 10 days before surgery for Graves' disease to decrease thyroid vascularity.

Should subclinical thyrotoxicosis be treated?

If serum TSH values are low because of overzealous treatment of hypothyroidism (in non-thyroid cancer patients), the dose of L-thyroxine should be lowered. The question of whether endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism should be treated remains controversial, but current guidelines based on available evidence recommend considering treatment when serum TSH values are persistently < 0.1 mU/l.22,23 Treatment of subclinical hyperthyroidism may decrease the risk of atrial fibrillation and may decrease the risk of low bone density in postmenopausal women.24,25 Once the decision has been made to treat subclinical hyperthyroidism, the goal of therapy is to normalise serum TSH values, preferably by using small doses of thionamides or, less advisably, definitive therapy with 131I.

Box 2: Unanswered questions and ongoing clinical trials

Unanswered research questions

What factors predict remission in Grave's disease patients?

What is the optimal dose and duration of anti-thyroid medication for Graves' disease?

What are the risks and benefits of treatment for subclinical hyperthyroidism?

Should antithyroid drugs be used before and after radioactive iodine treatment?

Current ongoing clinical trials

Block replacement therapy during radioiodine therapy (Odense University Hospital, Denmark)

Retuximab in the treatment of Graves' disease (Odense University Hospital, Denmark)

Lanreotide (somatuline autogel) in thyroid associated ophthalmopathy treatment (Ipsen, Paris, France)

Additional educational resources for healthcare professionals

Cooper DS. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 2003;362: 459-68

Abraham P, Avenell A, Watson WA, Park CM, Bevan JS. Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves' hyperthyroidism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4): CD003420.

Cooper DS. Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 905-17

Pearce EN, Farwell AP, Braverman LE. Thyroiditis. N Engl J Med 2003;348: 2646-5512826640

Cawood T, Moriarty P, O'Shea D. Recent developments in thyroid eye disease. BMJ 2004;329: 385-90

Information resources for patients

American Thyroid Association (www.thyroid.org)—Offers FAQs, a list of patient oriented books, lists of patient support organisations, and web brochures

Thyroid Foundation of America (www.allthyroid.org)—Offers information about thyroid disease and treatment as well as articles for patients

British Thyroid Foundation (www.btf-thyroid.org)—Provides some general information about the thyroid as well as numerous UK links

Thyroid Foundation of Canada (www.thyroid.ca)—Offers thyroid health guides in English and French

National Graves' Disease Foundation (www.ngdf.org)—A US-based patient support group. The web site includes a recommended reading list and downloadable brochures

When should general practitioners refer?

Because patients with thyrotoxicosis usually present to general practitioners rather than to specialists, it is essential for all medical practitioners to recognise typical signs and symptoms and to know how to initiate a diagnostic work-up. In most cases, once thyrotoxicosis has been detected, patients should be referred to an endocrinologist for management.w13 Coordination of care between general practitioners and endocrinologists is essential in order to provide optimal and cost effective care for patients with thyrotoxicosis.

Conclusions

Thyrotoxicosis can be readily diagnosed on the basis of serum thyroid function tests in patients with typical signs or symptoms. Several effective forms of therapy for thyrotoxicosis exist, all of which have advantages and disadvantages. The choice of treatment depends on the cause and severity of the thyrotoxicosis, as well as on patients' preferences. Box 2 gives information on unanswered research questions and ongoing clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

References w1-w13 are on bmj.com

References w1-w13 are on bmj.com

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cooper DS. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 2003;362: 459-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streetman DD, Khanderia U. Diagnosis and treatment of Graves' disease. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37: 1100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce EN, Farwell A, Braverman LE. Current concepts: thyroiditis. N Engl J Med 2003;348: 2646-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller AF, Drexhage HA, Berghout A. Postpartum thyroiditis and autoimmune thyroiditis in women of childbearing age: Recent insights and consequences for antenatal and postnatal care. Endocr Rev 2001;22: 605-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper DS. Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 905-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weetman AP, McGregor AM, Hall R. Evidence for an effect of antithyroid drugs on the natural history of Graves' disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1984;21: 163-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He CT, Hsieh AT, Pei D, Hung YJ, Wu LY, Yang TC, et al. Comparison of single daily dose methimazole and propylthiouracil in the treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60: 676-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham P, Avenell A, Watson WA, Park CM, Bevan JS. Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves' hyperthyroidism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4): CD003420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper DS, Goldminz D, Levin AA, Ladenson PW, Daniels GH, Molitch ME, et al. Agranulocytosis associated with antithyroid drugs. Effects of patient age and drug dose. Ann Intern Med 1983;98: 26-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woeber KA. Methimazole-induced hepatotoxicity. Endocr Pract 2002;8: 222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noh JY, Asari T, Hamada N, Makino F, Ishikawa N, Abe Y, et al. Frequency of appearance of myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO-ANCA) in Graves' disease patients treated with propylthiouracil and the relationship between MPO-ANCA and clinical manifestations. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54: 651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortimer RH, Cannell GR, Addison RS, Johnson LP, Roberts MS, Bernus I. Methimazole and propylthiouracil equally cross the perfused human term placental lobule. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82: 3099-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momotani N, Noh JY, Ishikawa N, Ito K. Effects of propylthiouracil and methimazole on fetal thyroid status in mothers with Graves' hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82: 3633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diav-Citrin O, Ornoy A. Teratogen update: antithyroid drugsmethimazole, carbimazole, and propylthiouracil. Teratology 2002;65: 38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizi F, Khoshniat M, Bahrainian M, Hedayati M. Thyroid function and intellectual development of infants nursed by mothers taking methimazole. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85: 3233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Momotani N, Yamashita R, Makino F, Noh JY, Ishikawa N, Ito K. Thyroid function in wholly breast-feeding infants whose mothers take high doses of propylthiouracil. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;53: 177-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm LE, Lundell G, Dahlqvist I, Israelsson A. Cure rate after I therapy for hyperthyroidism. Acta Radiol Oncol 1981;20: 161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nygaard B, Hegedus L, Ulriksen P, Nielsen KG, Hansen JM. Radioiodine therapy for multinodular toxic goiter. Arch Intern Med 1999;159: 1364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnema SJ, Bartalena L, Toft AD, Hegedus L. Controversies in radioiodine therapy: relation to ophthalmopathy, the possible radioprotective effect of antithyroid drugs, and use in large goitres. Eur J Endocrinol 2002;147: 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Bogazzi F, Manetti L, Tanda ML, Dell'Unto E, et al. Relation between therapy for hyperthyroidism and the course of Graves' ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1998;338: 73-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palit TK, Miller CC 3rd, Miltenburg DM. The efficacy of thyroidectomy for Graves' disease: A meta-analysis. J Surg Res 2000;90: 161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, Sawin CT, Col NF, Cobin RH, et al. Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management. JAMA 2004;29: 228-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gharib H, Tuttle RM, Baskin HJ, Fish LH, Singer PA, McDermott MT. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction: a joint statement on management from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, and the Endocrine Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90: 581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papi G, Pearce EN, Braverman LE, Betterle C, Roti E. A clinical and therapeutic approach to thyrotoxicosis with thyroid stimulating hormone suppression only. Am J Med 2005;118: 349-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toft AD. Clinical practice: subclinical hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med 2001;354: 512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.