Abstract

Calcium phosphate bioceramics, such as hydroxyapatite, have long been used as bone substitutes because of their proven biocompatibility and bone binding properties in vivo. Recently, a zirconia-hybridized pyrophosphate-stabilized amorphous calcium phosphate (Zr-ACP) has been synthesized, which is more soluble than hydroxyapatite and allows for controlled release of calcium and phosphate ions. These ions have been postulated to increase osteoblast differentiation and mineralization in vitro. The focus of this work is to elucidate the physicochemical properties of Zr-ACP and to measure cell response to Zr-ACP in vitro using a MC3T3-E1 mouse calvarial-derived osteoprogenitor cell line. Cells were cultured in osteogenic medium and mineral was added to culture at different stages in cell maturation. Culture in the presence of Zr-ACP showed significant increases in cell proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), and osteopontin (OPN) synthesis, whereas collagen synthesis was unaffected. In addition, calcium and phosphate ion concentrations and medium pH were found to transiently increase with the addition of Zr-ACP, and are hypothesized to be responsible for the osteogenic effect of Zr-ACP.

Keywords: amorphous phosphate, hydroxyapatite, MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts, alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin

INTRODUCTION

Calcium phosphate ceramics (e.g., hydroxyapatite (HAP), α-tricalcium phosphate) have long been studied for their capacity to repair osseous defects.1 These ceramics exhibit excellent biocompatibility and osteoconductivity, and bind directly to bone tissues in vivo.2–4 While porous scaffolds formed from these ceramics support repair of osseous defects in vivo, an osteoinductive effect of calcium phosphates has not been demonstrated.5,6 Given that calcium and phosphate ions are postulated regulators of osteoblastic differentiation7,8 and mineralization9,10 in vitro, a ceramic scaffold material capable of releasing these ions may prove osteoinductive, and accelerate healing of osseous defects in vivo by actively recruiting and directing the differentiation of host osteoprogenitor cells.

Amorphous calcium phosphates (ACPs) are more soluble than HAP, and will dissolve and convert to HAP under aqueous conditions.11 Because of their rapid and uncontrolled dissolution rates, ACPs have been used only sparingly as bone replacements.12,13 Recently, a pyrophosphate (P2074-)-stabilized, zirconia-hybridized amorphous calcium phosphate (Zr-ACP) has been synthesized.14,15 Such Zr-ACP has been shown to convert to HAP while maintaining substantial release of Ca2+ and PO43- ions in aqueous environments over long periods of time. Our hypothesis is that ions released from Zr-ACP will aid in the differentiation and maturation of osteoprogenitor cells.

To predict the effect of Zr-ACP on osteoprogenitor cells in an osseous defect, in vitro studies were performed using the MC3T3-E1 osteoprogenitor cell line. When cultured in the presence of osteogenic factors (i.e., ascorbate and β-glycerophosphate), these cells will develop phenotypic markers of osteoblastic differentiation,16,17 as they progress through three principal stages of cellular activity: proliferation, extracellular matrix maturation, and matrix mineralization.18 The first stage is marked by a rapid increase in cell number and accumulation of procollagen.16 The second stage, which occurs from 4 to 14 days after addition of ascorbate, is characterized by an increase of ALP activity and collagen accumulation in the extracellular matrix. The final stage is marked by expression of extracellular matrix proteins such as OPN and osteocalcin (OCN) and accumulation of mineral deposits.19,20

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of Zr-ACP with HAP on the chemistry of the cell culture environment and on phenotypic markers of osteoblastic differentiation. Changes in pH and ion concentration (Ca2+ and PO43-) were measured to determine dynamic effects of ACP dissolution on cell culture media. Subsequently, Zr-ACP and HAP were added to MC3T3-E1 cultures at distinct stages of osteoblastic differentiation, and cell number, ALP activity, and OPN and collagen synthesis were measured.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis and characterization of Zr-ACP and HAP

Zr-ACP was synthesized by utilizing a modified14 preparation protocol of Eanes et al.21 A precipitate formed instantaneously at 23°C upon rapidly mixing equal volumes of an 800 mmol/L Ca(NO3)2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) solution, a 536 mmol/L Na2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich) solution that contained a molar fraction of 2% Na4P2O7 (Sigma-Aldrich) as a stabilizing component for ACP, and an appropriate volume of a 250 mmol/L ZrOCl2 (GFS Chemicals, Columbus, OH) solution to achieve a mol fraction of 10% ZrOCl2 based on the calcium reactant. The reaction pH varied between 8.6 and 9.0. The suspension was filtered under suction, the solid phase was subsequently washed with the ice-cold ammoniated water and acetone (Fisher, Fairlawn, NJ), and then lyophilized (VirTis bench top freeze dry system, SP Industries, Warminster, PA) for 48 h at -70°C and 5 mTorr. HAP was prepared utilizing the same protocol except the pH of the reaction suspension was adjusted to 6.5. Maintaining the reaction pH below 7 is sufficient to accelerate the conversion of ACP into HAP.14

Minerals were milled in isopropanol and dried. For analysis of particle size, powders were dispersed in isopropanol, ultrasonicated for 15 min, and analyzed with a ShimadzuSA-CP3 centrifugal particle size analyzer (Columbia, MO). Concurrently, dry powders were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) from 15° to 70° 2θ with CuKα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm), using a XDS 2000 powder diffractometer (Scintag, Cupertino, CA) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. The sample was step-scanned in intervals of 0.020° 2θ at a scanning speed of 2.000 deg/min. Surface morphology, chemical composition, particle size, and the stability of Zr-ACP upon aqueous exposure have been extensively documented in literature.15,22,23

Physicochemical evaluation of calcium phosphates in growth medium

Changes in pH and concentrations of Ca2+ and PO43- ions were determined by addition of calcium phosphates to growth medium (minimum essential medium alpha modification (αMEM, Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Calabasas, CA) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin, fungizone; Invitrogen)). Growth medium was placed into a 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% relative humidity incubator for 24 h, and then Zr-ACP or HAP was added to concentration of 5 mg/mL. Thereafter, samples of medium were collected at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 12, 24, and 48 h. pH was measured, the medium was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm to sediment particulates, and the supernatant was collected. Ion concentrations were determined with a Dionex DX-120 (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) ion chromatograph, using an AS9-HC (Dionex) cation column and a CS12-A (Dionex) anion column for of Ca2+ and PO43-, respectively.

Cell culture

Cell studies were performed with the MC3T3-E1 cell line donated by Dr. A. J. García (Department of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA). Cells were maintained in growth medium and used at passages below 20. For studies, cells were lifted with trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen), seeded into 12-well culture plates (Corning, Corning, NY) at 50,000 cells/well with 2-mL growth medium, and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, designated as day 0, growth medium was replaced with differentiation medium (growth medium supplemented with 37.5 μg/mL L-ascorbate-2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich). Medium was replaced on days 3, 7, and 10. To determine the impact of Zr-ACP and HAP on the stages of cell development, material was added directly to cell culture at a concentration of 5 mg/mL at days 0, 1, 4, and 11. Cell number and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity were measured at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 for material addition at day 0, at days 5, 7, and 14 for material addition at day 4, and at days 12 and 14 for material addition at day 11. Osteopontin and collagen synthesis were measured at day 14 for mineral addition at days 1, 4, and 11.

Measurement of cell number

Fluorometric analysis of DNA content was used to determine the total number of cells for each condition as described previously.24 Measurements were made in duplicate with a DyNAQuant 200 (Hoefer, San Francisco, CA). A calibration curve showing a linear relationship between fluorescence and the concentrations of the DNA standards was used to determine DNA concentrations, and a conversion factor of 9.1 pg DNA/cell25 was used to calculate cell number.

Alkaline phosphatase activity

ALP activity, an early indicator of osteoblastic phenotype, was determined colorimetrically by the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenol phosphate at 30°C, using a commercially available kit (BioTron Diagnostics, Hemet, CA) as described in detail elsewhere.25,26 A Genesis 5 spectrophotometer (Spectronic Instruments, Rochester, NY) was used to measure absorbance at 405 nm at one-minute intervals for 4 min, and enzyme activity was calculated from the slope of absorbance versus time and then normalized by cell number.

Osteopontin synthesis

OPN, an extracellular matrix protein synthesized during the mineralization stage, was characterized by western blot analysis as described by Kreke et al.27 Equal volumes of cell lysate (3.5 μL/lane) were loaded onto a 7.5% SDS-PAGE running gel and separated at 125 V for 75 min. Proteins were transferred to Immune-blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and probed with rabbit anti-mouse OPN antibody (1/500 dilution, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1/15,000 dilution, Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate, Pierce Co., Rockford, IL) onto Kodak X-Omat film. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with HRP-conjugated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PHD) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Santa Cruz, CA) and again visualized by chemiluminescence. Band densities were determined using Scion Image (Scion Corporation), and OPN levels were normalized by G3PDH.

Collagen synthesis

Collagen synthesis was determined by the incorporation of radiolabeled proline (3H-proline) as described by Porter et al.24 Forty-eight hours prior to sample collection, a 1 μCi/μL 3H-proline stock solution (ICN, Irvine, CA) was added to the culture medium to a concentration of 3 μCi/mL. Cell layers were collected and total protein was separated into collagenase-digestible and noncollagenase-digestible fractions (designated CP and NCP, respectively). Counts were measured with a Tricarb 2100TR β-counter (Packard, Palo Alto, CA), using an emulsion-type liquid scintillant. Counts for collagenase-digestible and nondigestible fractions were normalized by the mean cell densities. The percent collagenous protein (%CP) for each sample was calculated using the following formula28:

The number 5.2 in this equation accounts for the relative abundance of proline in collagen.

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard error unless otherwise noted. Statistical analysis was performed using Origin® 6.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure with a significance level (α) of 0.05 was used to determine statistically significant differences between groups.

RESULTS

Physical characterization of minerals

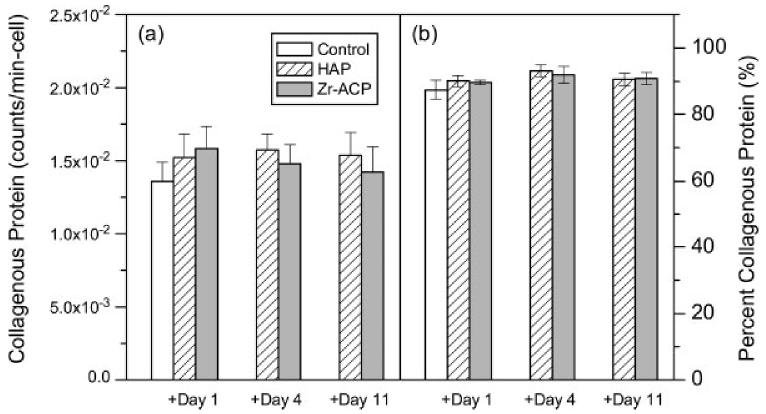

Particle size analysis showed that both HAP and Zr-ACP powders exhibited a broad distribution of sizes from less than 1 μm to greater than 80 μm. Median diameters were 6.7 ± 1.9 μm and 7.4 ± 2.3 μm for HAP and Zr-ACP, respectively. XRD was used to characterize the crystallinity of Zr-ACP and HAP. Diffraction patterns for Zr-ACP lack discrete diffraction peaks, indicating an amorphous structure [Fig. 1(a)], whereas HAP shows discrete diffraction peaks indicative of a crystalline structure [Fig. 1(b)].

Figure 1.

X-ray diffractometry. XRD patterns for (a) Zr-ACP and (b) HAP powders.

Calcium phosphate interaction with culture medium

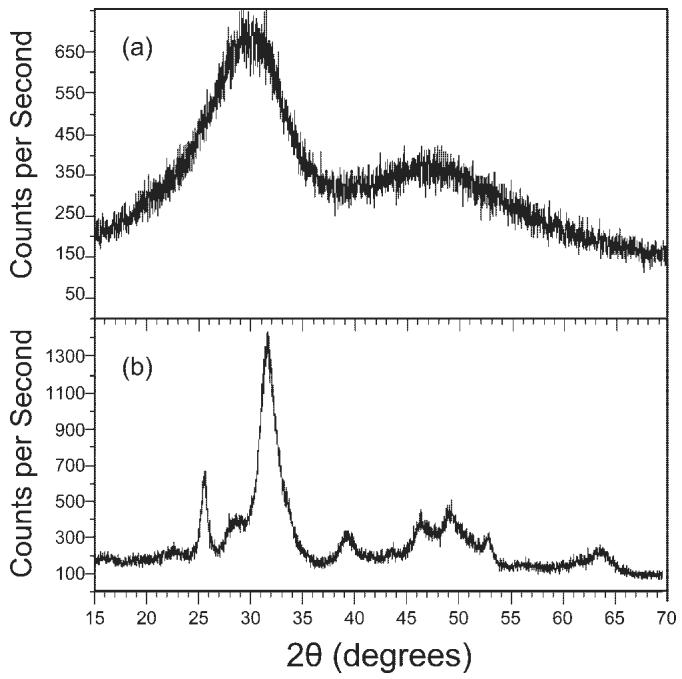

The amorphous structure of Zr-ACP has been shown to increase the solubility of Zr-ACP and subsequently the release of Ca2+ and PO43- ions relative to HAP.14 To determine the dynamic effects of Zr-ACP and HAP in tissue culture, minerals were added to growth medium and analyzed at discrete points in time. Ion chromatography confirmed changes in PO43- [Fig. 2(a)] and Ca2+ [Fig. 2(b)], with addition of 5 mg/mL of Zr-ACP or HAP. Addition of Zr-ACP resulted in significantly elevated phosphate concentrations of 0.585 ± 0.004 mM at 15 min and 0.281 ± 0.003 mM at 2 days, relative to 0.192 ± 0.002 mM for control. Concurrently, calcium concentration was significantly greater than control at 15 min, but significantly lower than control at 2 days (1.58 ± 0.002 mM and 0.300 ± 0.002 mM, compared with 0.847 ± 0.002 mM). Both Ca2+ and PO43- ions concentrations were significantly higher at 15 min than at 2 days, consistent with transient release of ions and subsequent precipitation. Addition of HAP resulted in significantly lower PO43- and Ca2+ concentrations at 1 h (0.152 ± 0.002 mM and 0.706 ± 0.004 mM, respectively) and 2 days (0.145 ± 0.005 mM and 0.279 ± 0.003 mM, respectively), suggesting that a calcium phosphate mineral may have precipitated out of solution.

Figure 2.

Ion concentration. (a) Phosphate and (b) calcium ion concentration in growth medium following addition of 5 mg/mL Zr-ACP and HAP. Dotted lines represent concentrations for n = 2 control samples. Bars represent the mean ± standard error for n = 2 samples. All measurements are significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.05) except calcium concentration at 15 min after addition of HAP.

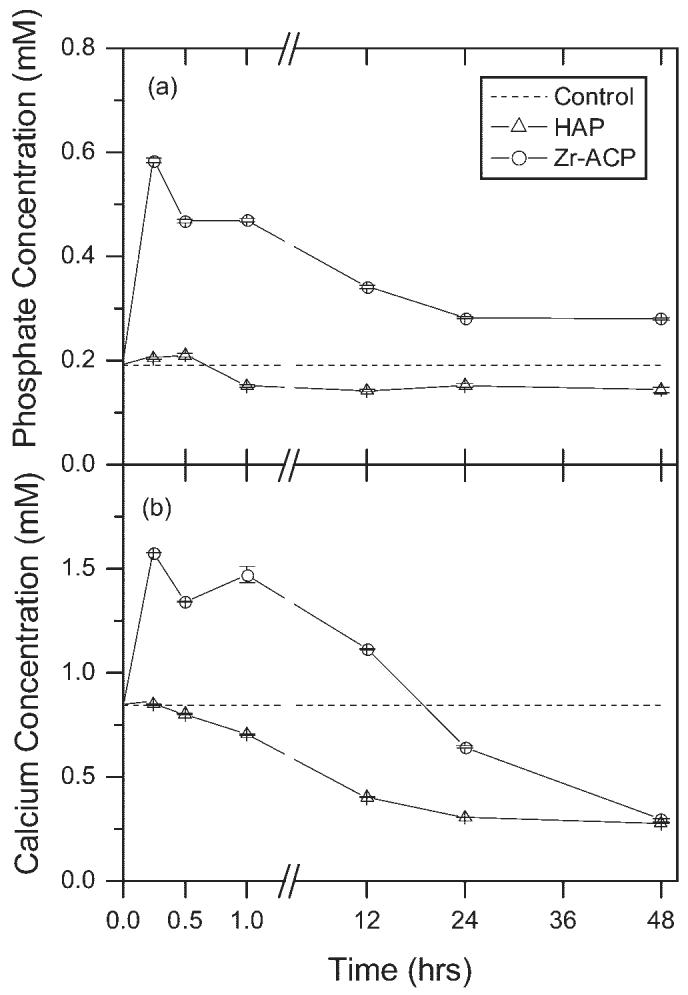

In the absence of added mineral, the pH of growth medium remained constant for the first 12 h, but steadily declined from 12 to 48 h (Fig. 3). When 5 mg/mL Zr-ACP was added, pH was significantly higher than control at 15 min (7.53 ± 0.01 compared with 7.36 ± 0.01), but also exhibited a steady decline from 12 to 48 h. In contrast, addition of 5 mg/mL of HAP did not cause any change in pH during the first 1 h, but pH was elevated relative to control at 12 h (7.39 ± 0.01 compared with 7.35 ± 0.01), and exhibited a steady decline from 12 to 48 h.

Figure 3.

pH as a function of time. Change in pH of growth medium with addition of Zr-ACP or HAP. Bars represent the mean ± standard error for n = 4 samples. An asterisk indicates statistical difference from the control group (p ≤ 0.05).

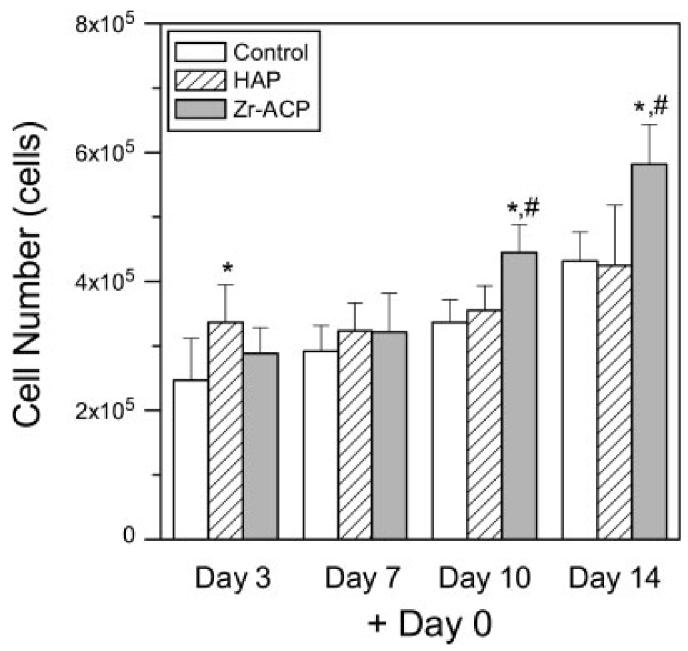

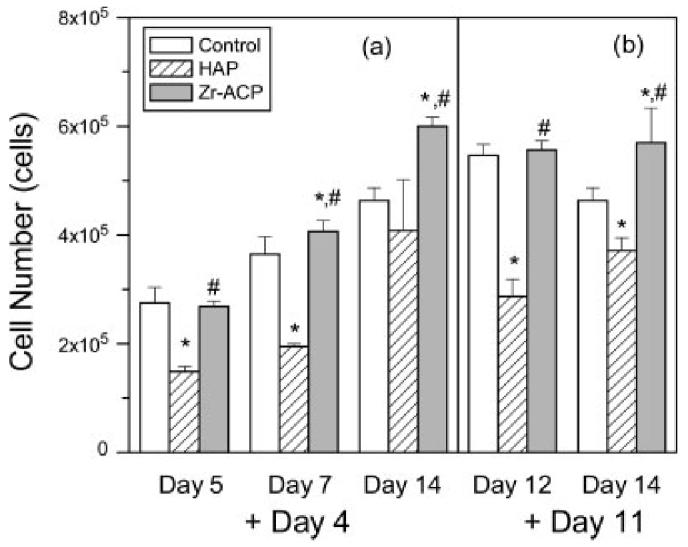

Cell number

To determine the effect of minerals on cell proliferation, cell number was measured at discrete intervals after mineral addition. When HAP was added at day 0 (defined as the day ascorbate was added to culture medium), cell number was significantly different from the control at day 3 (Fig. 4). However, when Zr-ACP was added at day 0, cell density was significantly higher (p < 0.05) at days 10 and 14 as compared with the control. When HAP was added at days 4 or 11, cell number was significantly decreased relative to control (Fig. 5). In contrast, when Zr-ACP was added at days 4 or 11, cell number was not different from control at early time points, but was statistically greater than control at day 14.

Figure 4.

Cell number. Zr-ACP or HAP (5 mg/mL) was added at day 0 and cells were assayed at days 3, 7, 10, and 14. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error for n = 8 wells. An asterisk indicates statistical difference from the control group (p ≤ 0.05), and a pound symbol indicates statistical difference from the HAP group (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Cell number. Zr-ACP or HAP (5 mg/mL) was added at (a) day 4 and assayed at days 5, 7, and 14, and (b) added at day 11 and assayed at days 12 and 14. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error for n = 8 wells. An asterisk indicates statistical difference from the control group (p ≤ 0.05), and a pound symbol indicates statistical difference from the HAP group (p ≤ 0.05).

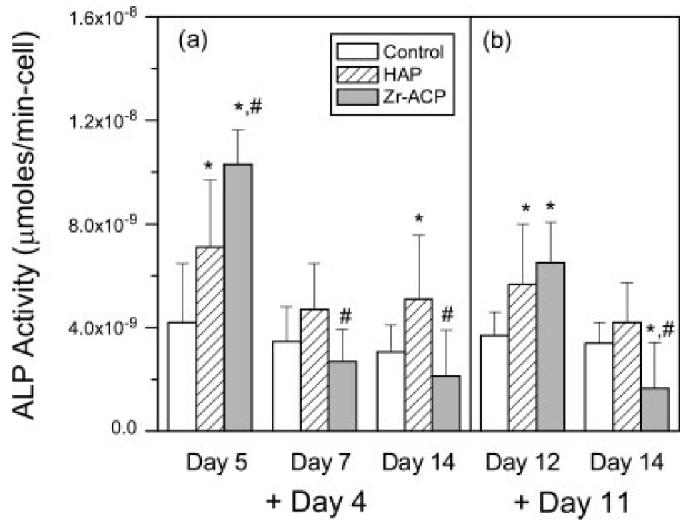

Alkaline phosphatase activity

Cells were assayed for alkaline phosphatase activity to determine the effect of mineral addition on the progression of MC3T3-E1 differentiation towards the osteoblastic phenotype (Fig. 6). When Zr-ACP or HAP was added at days 4 or 11, ALP activity on the following day was significantly greater than control (days 5 and 12, respectively), but not at the subsequent time point (days 7 and 14, respectively). This transient effect was more pronounced with mineral addition at day 4 than day 11. In addition, when minerals were added at day 0, ALP activity at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 was not statistically different from control (data not shown). These results indicate that addition of Zr-ACP to cell culture significantly increases ALP activity transiently and in a manner dependent on osteoblastic maturity.

Figure 6.

Alkaline phosphatase activity. Zr-ACP or HAP (5 mg/mL) was (a) added at day 4 and assayed at days 5, 7, and 14, and (b) added at day 11 and assayed at days 12 and 14. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error for n = 8 wells. An asterisk indicates statistical difference from the control group (p ≤ 0.05), and a pound symbol indicates statistical difference from the HAP group (p ≤ 0.05).

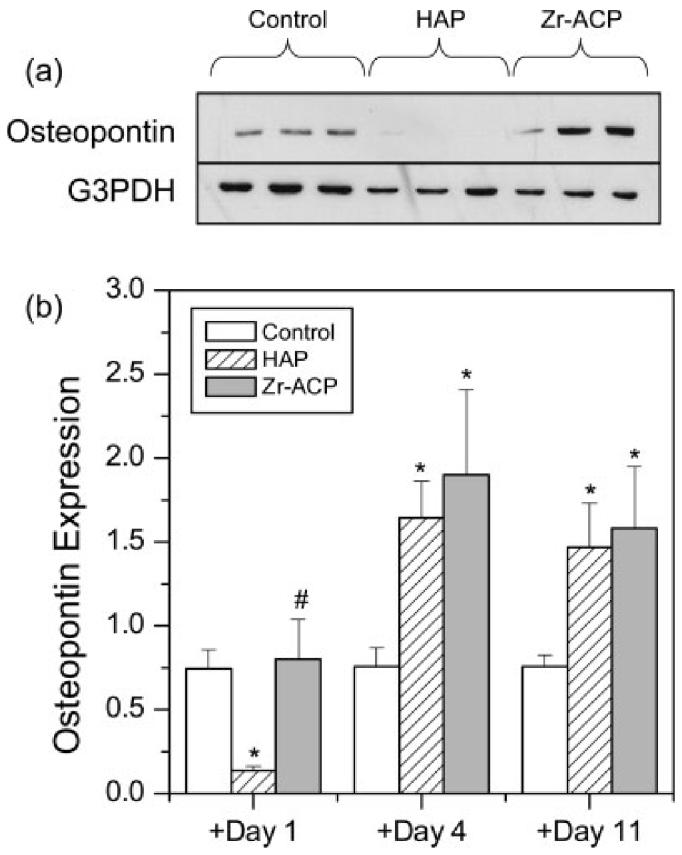

Osteopontin expression

Cells were assayed at day 14 for osteopontin synthesis, a phenotypic marker of the mineralization stage of osteoblastic differentiation. Representative protein bands for mineral addition at day 1 show that HAP significantly diminished OPN synthesis relative to controls [Fig. 7(a)]. When OPN band densities were normalized by G3PDH, western blots indicated an 80% decrease in OPN with HAP addition, but no effect of Zr-ACP addition at day 1 relative to control [Fig. 7(b)]. In contrast, a 100% increase (p < 0.05) in OPN synthesis relative to control was measured for addition of both Zr-ACP and HAP when added at days 4 or 11 as compared with the control.

Figure 7.

Osteopontin expression. (a) Representative bands for OPN and G3PDH for cells cultured at 14 days where 5 mg/mL of Zr-ACP or HAP or no mineral was added at day 0. Each lane represents one replicate (well). (b) Relative OPN band densities (normalized by G3PDH) versus addition time of minerals. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error for n = 6 wells. An asterisk indicates statistical difference from the control group (p ≤ 0.05), and a pound symbol indicates statistical difference from the HAP group (p ≤ 0.05).

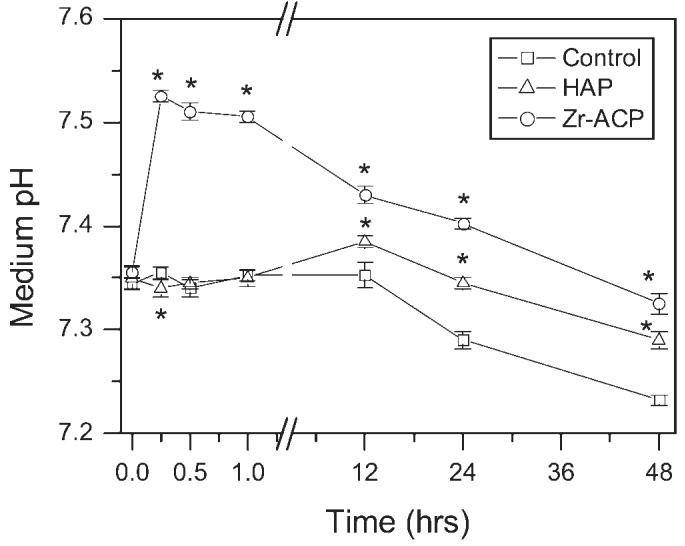

Collagen synthesis

Cells were assayed for the rate of collagen synthesis by incorporation of 3H-proline during the period from day 12 to day 14. Scintillation counting of the collagenase-digestible protein fraction on day 14 revealed a modest but statistically insignificant increase in collagen synthesis rate per cell, with the addition either HAP or Zr-ACP on either day 1, 4, or 11 relative to control [Fig. 8(a)]. When calculated as a fraction of total protein synthesized, no difference was found with the addition of either mineral [Fig. 8(b)]. Together they indicate that collagen synthesis was not significantly affected by either HAP or Zr-ACP.

Figure 8.

Collagen synthesis. (a) Counts per minute from collagen protein fractions normalized by mean cell number and (b) collagenous protein as a percentage of the total protein synthesized plotted versus addition time of minerals. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error for n = 4 wells.

DISCUSSION

Although numerous biocompatible materials have been identified as suitable fillers for osseous defects, the long-term efficacy of these materials in vivo may depend on their capacity to stimulate beneficial host responses, such as integration, vascular infiltration, and osteogenesis. Previous studies have demonstrated that hydroxyapatite and other relatively insoluble calcium phosphates are attractive substrates that support cell adhesion and expression of the osteoblastic phenotype.29–32 In contrast, amorphous calcium phosphates—which exhibit a relatively high solubility— may offer a means to deliver ions that can facilitate the process of osteoblastic differentiation. This study indicates that Zr-ACP—when added to cell cultures— increases OPN synthesis and ALP activity in a manner comparable to that of HAP, but achieves a greater cell density than HAP.

To test the capacity for Zr-ACP to deliver ions, measurements of the mean solution pH and Ca2+ and PO43- concentrations were made with the addition of mineral to growth medium. Although both serum proteins and NaHCO3 in the medium possess buffering capacity, a transient increase in the mean pH was measured over a 24 h period following addition of Zr-ACP, but not HAP (Fig. 3). Such an increase in pH may facilitate osteoblastic differentiation by enhancing gap junctional connectivity,33 which itself is critical for ALP activity, synthesis of OPN and OCN, and matrix mineralization.34 Further, an increase in pH may enhance precipitation of Ca2+ and PO43- ions, and activity of ALP (which is maximal at pH 9–11). Measurement of ion concentrations revealed transient increases in both Ca2+ and PO43- over a 24-h period with maximal increases of 1.58 mM Ca2+ and 0.59 mM PO43- at 15 min (Fig. 2). Although HAP did not cause a transient increase in ion concentration, both HAP and Zr-ACP demonstrated a steady decrease in Ca2+. Such an extraction of ions from the medium has been reported previously with calcium phosphate,35 titanium,36 and titania substrates,37 and is hypothesized to be associated with the formation of an osteoconductive apatite film.

To characterize the osteogenic effect of minerals, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in medium supplemented with ascorbate, and mineral particles were added to the culture wells. Normally, β-glycerol phosphate is included in osteogenic culture media, and—as a substrate for alkaline phosphatase—its hydrolysis increases phosphate concentration and pH in the cell microenvironment. Its inclusion has been shown to be critical for the synthesis of OPN and OCN18 and deposition of calcium-phosphate minerals by MC3T3-E1 cells.17 In addition, it has been shown to act synergistically with ascorbate to stimulate ALP activity,16 but not to affect cell proliferation or collagen synthesis.17 For these studies, it was excluded from the cell culture medium to establish a more rigorous test of the biologic effects of ions released by Zr-ACP.

The initial stage of osteoblast development is characterized by active replication of undifferentiated cells.16 In this study, cell densities at days 3 and 7 were largely unaffected by the addition of Zr-ACP or HAP on day 0, consistent with a previous study in which medium was supplemented with 1.8 mM calcium and 5 mM inorganic phosphate.9 In contrast, Lossdorfer et al.7 demonstrated modulation in cell number when osteoblasts were grown on calcium- and phosphate-eluting bioactive glass substrates of differing compositions. Nevertheless, two statistically significant differences in cell number were observed with the addition of minerals. First, cell number was decreased relative to control when cells were exposed to HAP on days 4 or 11 (Fig. 5). Although HAP is considered to be a well-tolerated material, in vitro studies have shown that phagocytic activity of osteoblasts may have toxic effects when HAP particle sizes are less than about 5 μm.38,39 In this study, the median particle size for HAP was 6.7 μm. Second, cell number was consistently significantly higher at day 14 when Zr-ACP was added, relative to the control (Figs. 4 and 5). The cause of this effect is unknown, but given its appearance late in the culture period may be associated with the formation of multilayer cell structures.

The second stage of osteoblastic differentiation is marked by increased ALP activity and collagen accumulation in the extracellular matrix. Analysis of ALP activity demonstrated that addition of both Zr-ACP and HAP enhanced ALP activity in a transient manner. This phenomenon was observed with addition at days 4 and 11, but not day 0, suggesting that this effect is dependent on cell maturity. Further, this effect was more pronounced with the addition of Zr-ACP, suggesting that a transient increase in pH—which is known to enhance gap junctional communication33—is a contributing factor. Analysis of collagen synthesis indicated a small, but statistically insignificant increase with addition of both Zr-ACP and HAP. The similar collagen levels for the two materials suggest that expression of this phenotypic marker is modestly sensitive to the osteoconductive properties of the added minerals, but was unaffected by the dissolution and conversion of Zr-ACP to HAP. Previous work has shown that collagen synthesis by osteoblasts is facilitated by a slightly alkaline pH,40 which would occur during Zr-ACP dissolution. However, in our study, 3H-proline was added at day 12 (at least one day after addition of Zr-ACP) and therefore might not reveal a phenotypic response to a Zr-ACP-induced pH transient.

The third stage of osteoblastic differentiation is marked by synthesis of OPN, OCN, and deposition of calcium-phosphate mineral. OPN is a phosphoprotein that possesses both an Arg-Gly-Asp sequence—that mediates integrin binding18—and abundant aspirate and phosphorylated serine residues that bind calcium phosphate crystals and are thought to regulate crystal growth.41–43 Our findings demonstrate that Zr-ACP and HAP when added at days 4 and 11 significantly increased OPN synthesis relative to control, consistent with previous studies using various calcium phosphates.44,45 The similar OPN levels for the two materials here—like those observed for collagen synthesis—suggest that the cells are responding to the osteoconductive properties of the minerals.

Although this study focused on the role of Zr-ACP in vitro, its behavior within a bony abscess is expected to differ as a consequence of both the physiology of the implant site and the mechanical requirements of an implantable material. Osteoclastic activity driving bone deconstruction is anticipated to lower the local pH, which would accelerate dissolution of Zr-ACP and increase ion concentration in the wound site. However, this effect may be offset by interstitial flow, which could dissipate the ionic plume. Concurrently, structural rigidity of the implant may dictate the development of ACPs with either slower or more sustained release characteristics.

Nevertheless, this study showed that Zr-ACP undergoes a process of dissolution that is marked by transient increases in Ca2+ and PO43- ions and pH that coincide with a transient increase in ALP activity. Addition of Zr-ACP had a significant effect on OPN synthesis and a modest effect on collagen synthesis, which were similar to those with the addition of HAP. This suggests that synthesis of these two matrix proteins by MC3T3-E1 cells is stimulated by the osteoconductive properties of minerals, but that the MC3T3-E1 phenotype is not affected by ions released from Zr-ACP. In future work, a family of ACPs with different conversion dynamics will be tested to determine whether transient increases in ALP activity correlate with dissolution kinetics. In addition, subsequent work will involve the use of bone marrow-derived osteoprogenitor cells, which are untransformed progenitor cells (a more relevant model for studying bone healing46), but also plastic and more sensitive to culture history.24,27

Footnotes

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; contract grant number: R03-DE015229

References

- 1.Bohner M. Calcium orthophosphates in medicine: From ceramics to calcium phosphate cements. Injury. 2000;31(Suppl 4):37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)80022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggli PS, Muller W, Schenk RK. Porous hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate cylinders with two different pore size ranges implanted in the chancellors bone of rabbits. A comparative histomorphometric and histologic study of bony in-growth and implant substitution. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saffar JL, Colombier ML, Detienville R. Bone formation in tricalcium phosphate-filled periodontal intrabony lesions. Histological observations in humans. J Periodontol. 1990;61:209–216. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.4.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO, Milam SB. Reconstruction of bone using calcium phosphate bone cements: A critical review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1122–1126. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goshima J, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Osteogenic potential of culture-expanded rat marrow cells as assayed in vivo with porous calcium phosphate ceramic. Biomaterials. 1991;12:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90209-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris CT, Cooper LF. Comparison of bone graft matrices for human mesenchymal stem cell-directed osteogenesis. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:747–755. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lossdorfer S, Schwartz Z, Lohmann CH, Greenspan DC, Ranly DM, Boyan BD. Osteoblast response to bioactive glasses in vitro correlates with inorganic phosphate content. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2547–2555. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tenenbaum HC, Heersche JN. Differentiation of osteoblasts and formation of mineralized bone in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 1982;34:76–79. doi: 10.1007/BF02411212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang YL, Stanford CM, Keller JC. Calcium and phosphate supplementation promotes bone cell mineralization: Implications for hydroxyapatite (HA)-enhanced bone formation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52:270–278. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<270::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeno S, Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Morioka H, Yatabe T, Funayama A, Toyama Y, Taguchi T, Tanaka J. The effect of calcium ion concentration on osteoblast viability, proliferation and differentiation in monolayer and 3D culture. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4847–4855. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eanes ED. Amorphous calcium phosphate: Thermodynamic and kinetic considerations. In: Amjed Z, editor. Calcium Phosphates in Biological and Industrial Processes. Kluwer Academic; Boston, MA: 1998. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ter Brugge PJ, Wolke JG, Jansen JA. Effect of calcium phosphate coating composition and crystallinity on the response of osteogenic cells in vitro. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:472–480. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxian SH, Zawadsky JP, Dunn MG. In vitro evaluation of amorphous calcium phosphate and poorly crystallized hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:111–117. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skrtic D, Antonucci JM, Eanes ED, Brunworth RT. Silica- and zirconia-hybridized amorphous calcium phosphate: Effect on transformation to hydroxyapatite. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:597–604. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skrtic D, Antonucci JM, Eanes ED, Eidelman N. Dental composites based on hybrid and surface-modified amorphous calcium phosphates. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quarles LD, Yohay DA, Lever LW, Caton R, Wenstrup RJ. Distinct proliferative and differentiated stages of murine MC3T3–E1 cells in culture—An in vitro model of osteoblast development. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:683–692. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franceschi RT, Iyer BS. Relationship between collagen synthesis and expression of the osteoblastic phenotype in MC3T3–E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:235–246. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lian JB, Stein GS. Concepts of osteoblast growth and differentiation—Basis for modulation of bone cell development and tissue formation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1992;3:269–305. doi: 10.1177/10454411920030030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauschka PV, Wians FH. Osteocalcin-hydroxyapatite interaction in the extracellular organic matrix of bone. Anat Rec. 1989;224:180–188. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092240208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldberg A, Franzen A, Heinegard D. Cloning and sequence analysis of rat bone sialoprotein (osteopontin) cDNA reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8819–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eanes ED, Gillesen H, Posner AS. Intermediate states in the precipitation of hydroxyapatite. Nature. 1965;208:365–367. doi: 10.1038/208365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skrtic D, Antonucci JM, Eanes ED. Amorphous calcium phosphate-based bioactive polymeric composites for mineral tissue regeneration. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 2003;108:167–182. doi: 10.6028/jres.108.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonucci JM, Skrtic D. Matrix resin effects on selected physicochemical properties of amorphous calcium phosphate composites. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2005;20:29–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter RM, Huckle WR, Goldstein AS. Effect of dexamethasone withdrawal on osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:13–22. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badami AS, Kreke MR, Thompson MS, Riffle JS, Goldstein AS. Effect of fiber diameter on spreading, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblastic cells on electrospun poly(lactic acid) substrates. Biomaterials. 2006;27:596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein AS, Juarez TM, Helmke CD, Gustin MC, Mikos AG. Effect of convection on osteoblastic cell growth and function in biodegradable polymer foam scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreke MR, Huckle WR, Goldstein AS. Fluid flow stimulates expression of osteopontin and bone sialoprotein by bone marrow stromal cells in a temporally dependent manner. Bone. 2005;36:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishaug SL, Yaszemski MJ, Bizios R, Mikos AG. Osteoblast function on synthetic biodegradable polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1994;28:1445–1453. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820281210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massas R, Pitaru S, Weinreb MM. The effects of titanium and hydroxyapatite on osteoblastic expression and proliferation in rat parietal bone cultures. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1005–1008. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oonishi H. Orthopaedic applications of hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials. 1991;12:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90196-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozawa S, Kasugai S. Evaluation of implant materials (hydroxyapatite, glass-ceramics, titanium) in rat bone marrow stromal cell culture. Biomaterials. 1996;17:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)80751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vrouwenvelder WC, Groot CG, de Groot K. Histological and biochemical evaluation of osteoblasts cultured on bioactive glass, hydroxylapatite, titanium alloy, and stainless steel. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:465–475. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi DT, Huang JT, Ma D. Regulation of gap junctional intercellular communication by pH in MC3T3–E1 osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1891–1899. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiller PC, D'Ippolito G, Balkan W, Roos BA, Howard GA. Gap-junctional communication is required for the maturation process of osteoblastic cells in culture. Bone. 2001;28:362–369. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radin S, Ducheyne P, Berthold P, Decker S. Effect of serum proteins and osteoblasts on the surface transformation of a calcium phosphate coating: A physicochemical and ultrasound study. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39:234–243. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199802)39:2<234::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Ducheyne P. Quasi-biological apatite film induced by titanium in a simulated body fluid. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:341–348. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980905)41:3<341::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Areva S, Paldan H, Peltola T, Narhi T, Jokinen M, Linden M. Use of sol–gel-derived titania coating for direct soft tissue attachment. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70:169–178. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans EJ. Toxicity of hydroxyapatite in vitro: The effect of particle size. Biomaterials. 1991;12:574–576. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90054-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alliot-Licht B, Gregoire M, Orly I, Menanteau J. Cellular activity of osteoblasts in the presence of hydroxyapatite: An in vitro experiment. Biomaterials. 1991;12:752–756. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bushinsky DA. Metabolic alkalosis decreases bone calcium efflux by suppressing osteoclasts and stimulating osteoblasts. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F216–F222. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.1.F216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denhardt DT, Noda M. Osteopontin expression and function: Role in bone remodeling. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1998;30–31:92–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boskey AL, Maresca M, Ullrich W, Doty SB, Butler WT, Prince CW. Osteopontin-hydroxyapatite interactions in vitro: Inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation and growth in a gelatin-gel. Bone Miner. 1993;22:147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter GK, Hauschka PV, Poole AR, Rosenberg LC, Goldberg HA. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochem J. 1996;317:59–64. doi: 10.1042/bj3170059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park EK, Lee YE, Choi JY, Oh SH, Shin HI, Kim KH, Kim SY, Kim S. Cellular biocompatibility and stimulatory effects of calcium metaphosphate on osteoblastic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3403–3411. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oreffo RO, Driessens FC, Planell JA, Triffitt JT. Growth and differentiation of human bone marrow osteoprogenitors on novel calcium phosphate cements. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1845–1854. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bianco P, Robey PG. Stem cells in tissue engineering. Nature. 2001;414:118–121. doi: 10.1038/35102181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]