Abstract

Currently, there are no approved medications for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the United States. The effectiveness of duloxetine in the treatment of SUI is linked to its inhibition of presynaptic neuronal reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the central nervous system, resulting in elevated levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft. In animal studies, this agent leads to an increase in nerve stimulation to the urethral striated sphincter muscle. A similar mechanism in women is believed to result in stronger urethral contractions, with improved sphincter tone during urine storage and physical stress. In 3 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, patients receiving duloxetine had a statistically significant and clinically relevant reduction in the number of incontinence episodes and a corresponding improvement in quality of life. If this use of duloxetine is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, as it has been by the European regulatory agencies, it will be the first drug indicated for the treatment of SUI. This pharmacologic therapy is an additional option for women and is likely to become an integral component of patient management.

Key words: Stress urinary incontinence, Urodynamics, Urethra, Duloxetine hydrochloride

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a major urologic health care issue, affecting 25 million American women.1 The etiology of SUI is multifactorial, thus treatment is frequently difficult. Many women endure this problem silently while their quality of life suffers. Currently, surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment; however, success rates hover around 82%, and surgery is often not an option in an elderly population with high morbidity.2 Biofeedback and behavior modification have also been used, but these conservative therapies frequently fail or are unsatisfactory for patients with severe SUI. Pharmacotherapies have been used in the past, but none were U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved or very successful. Duloxetine hydrochloride, a selective reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine, was approved by the regulatory agency in the European Union in the fall of 2004 but has not been approved in the United States. It has recently demonstrated promise in the treatment of SUI in several phase III clinical studies. The purpose of this article is to review the most current literature on duloxetine that discusses the efficacy and safety of this drug as a pharmacologic therapy for women with SUI.

Continence Mechanisms

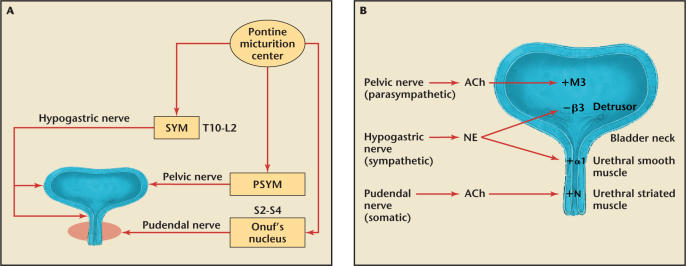

The anatomic mechanisms that maintain urinary continence during elevation of abdominal pressure include both passive and active closure of the urethra. A passive closure mechanism involves the essentially simultaneous transmission of intra-abdominal pressure to the urinary bladder and proximal urethra, and this has been considered to play an important role in urinary continence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Neurocontrol of the lower urinary tract. The sympathetic nerve (SYM) from spinal cord levels T10-L2 innervates the urinary tract via the hypogastric nerve. The parasympathetic nerve (PSYM) from the S2–S4 levels innervates the bladder via the pelvic nerve. The somatic nerve controlling the rhabdosphincter is innervated by the pudendal nerve from Onuf's nucleus in the sacral S2–S4 levels of the spinal cord. (B) Anatomy of the lower urinary tract, the nerves that innervate it and key neurotransmitters. Ach, acetylcholine; NE, norepinephrine; +M3, muscarinic receptor type 3, mainly in the detrusor smooth muscle that contracts the bladder; −β3, β3-adrenergic receptors in the detrusor smooth muscle that relax the bladder during urine storage; +α1, α1 adrenergic receptors that contract the smooth muscle of the internal sphincter; +N, nicotinic receptors that contract the external sphincter (rhabdosphincter).

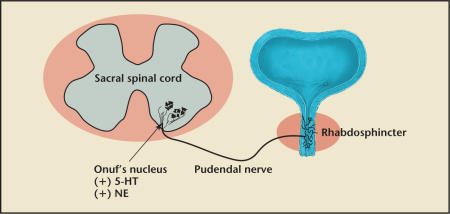

The external urethral sphincter (EUS) contracts during closure of the urethra. The EUS, often referred to as the rhabdosphincter, can be activated voluntarily or by reflex mechanisms elicited by bladder distension. Nerve tracts from the central nervous system terminate at Onuf's nucleus in the sacral spinal cord (S2–S4) and synapse with the pudendal nerve (Figure 2). Serotonin and norepinephrine are two key neurotransmitters that stimulate the proximal end of the pudendal nerve to control the contraction of the EUS.3 During a sudden stress on the pelvic floor, such as coughing, sneezing, or laughing, a guarding reflex is elicited.4 The guarding reflex refers to an increase in pressure in the middle urethra. The EUS helps to maintain continence by contracting to “guard” against the increased bladder pressure to prevent leakage.

Figure 2.

The pudendal nerve innervation of the external urethral sphincter (rhabdosphincter) is from Onuf's nucleus of the sacral spinal cord. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) are the 2 key neurotransmitters that modulate contraction of the sphincter to help maintain sufficient urethral closure.

New Research in SUI

A popular classification system for SUI includes 2 major types: urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD).5,6 (See Sidebar, “Challenging the ‘I’ in ISD.”) Urethral hypermobility is the displacement of the bladder neck, resulting in a lack of intra-abdominal pressure transmission to the proximal urethra. In contrast, ISD is characterized by a malfunction of the urethral sphincter closure mechanism.

ISD has recently been reported to be more common than previously thought in patients with SUI.7 Therefore, it seems important to further clarify the active urinary closure mechanism under stress conditions. The details of urethral closure mechanisms during stress conditions (eg, coughing or sneezing) have been studied in dogs, and the 2 components (passive and active) of urethral closure mechanisms were detected.8–10

Our group has recently been involved in the development of a new animal model of SUI to clarify urinary continence mechanisms during the elevation of intra-abdominal pressure. The well-studied anatomy of the rat makes it a useful animal model, and the arrangement of the smooth and striated muscles of the urethra in the female rat is similar to that in humans.11,12

The experimental data from animal models suggest that the middle urethra is critical for maintaining continence. The middle urethral response to sneezing was more intense than either the bladder or proximal urethra response and involved both active and passive mechanisms. The active closure in the middle urethra was not related to the magnitude of bladder responses, and therefore the guarding reflex acts as an “on-off” switch. Moreover, the middle urethral response started before the bladder response began. Surprisingly, the response in the proximal urethra was negligible when corrected for the bladder response. The increase in proximal urethral pressure largely results from passive transmission of intra-abdominal pressure to the proximal urethra. The distal urethra seems to serve a limited role in the continence mechanism (Figure 1).

These studies highlight the importance of the pudendal nerve, middle urethra, and EUS in maintaining continence. By extension to humans, basic research suggests that regardless of the clinical diagnosis (eg, urethral hypermobility or ISD), the middle urethra and EUS could be a primary focus in the management of SUI. Treatment options that increase the pressure in the middle urethra under stress conditions could be beneficial to patients with either urethral hypermobility or ISD. Future therapies might include the use of muscle-derived stem cells as a potential source of a nonimmunogenic, nonmigratory injectable agent to treat SUI, not only by bulking but perhaps also by restoring muscle to the urethral sphincter.13

SUI Pharmacotherapy

Currently, there are no approved medications for the treatment of SUI in the United States. Alpha adrenoceptor agonists, such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, have all been reported to be effective in SUI, even though they lack selectivity for urethral α adrenoreceptors. Thus, cardiovascular safety is an issue, and concerns over hemorrhagic strokes have restricted the availability of these agents in the United States. Imipramine has been used for the treatment of SUI, but no randomized clinical trials supporting its use have been reported. In recent years, there has been a push to look for other drugs that would be both efficacious and safe.

Duloxetine is a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. The effectiveness of duloxetine in the treatment of SUI is linked to its inhibition of presynaptic neuronal reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the central nervous system (sacral spinal cord), resulting in elevated levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft. In animal studies, this agent leads to an increase in nerve stimulation to the striated urethral sphincter muscle. This is manifested by an 8-fold increase in electromyographic activity of the muscle during the storage phase of the micturition cycle.14 A similar mechanism in women is believed to result in stronger urethral contractions, with improved sphincter tone during urine storage and physical stress. The effect of duloxetine on the striated urethral sphincter is unique to the dual reuptake inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine in a single molecule and is not duplicated by the administration of 2 separate single reuptake inhibitors simultaneously.

Phase III Clinical Trials

Three recently published studies evaluated the efficacy and safety of duloxetine as a pharmacologic therapy for women with SUI. Dmochowski and colleagues,15 Van Kerrebroeck and colleagues,16 and Millard and colleagues17 have all reported data on the efficacy and tolerability of duloxetine in women from North America, Western Europe, and various other countries, respectively. In these randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, the investigators enrolled a total of 1635 adult women who were randomized to duloxetine 40 mg twice daily (n = 818) or placebo (n = 817) for 12 weeks. The studies enrolled subjects according to a clinical diagnostic algorithm for SUI based on symptoms and signs, without requiring formal urodynamic testing before enrollment. The studies probably reflect the type of patient who will receive pharmacologic treatment for SUI, thus increasing the generalizability of the results. The primary efficacy measures were incontinence episode frequency (IEF) as reported in patient-completed, real-time diaries and a validated incontinence-specific quality-of-life questionnaire (I-QOL) score. A secondary end point was the validated patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I) rating.

In each of the 3 studies, the duloxetine-treated patient group had a 50% or greater median decrease in IEF. Patients receiving placebo experienced 27.5%–40% median reductions in IEF. The difference between duloxetine and placebo was significant in all 3 studies. In each study, the duloxetine IEF improvements were reported within the first 4 weeks of treatment and were maintained throughout the trial.

Health-related quality of life was measured with the I-QOL questionnaire. I-QOL total scores were significantly improved in the duloxetinetreated group compared with the placebo group in 2 of the 3 clinical trials. To evaluate patients' general assessment of improvement during therapy, women were also asked to respond to the PGI-I question. Significantly more women using duloxetine considered their symptoms of SUI improved (as denoted by “a little better,” “much better,” or “very much better” response to the PGI-I) compared with women using placebo in 2 of the 3 studies. The most commonly reported side effects included nausea, dry mouth, difficulty sleeping, tiredness, constipation, and dizziness. These were generally reported to be mild to moderate and usually disappeared within the first few weeks of treatment. Other side effects were reported less frequently.

The primary statistical analyses were performed according to intent-to-treat (ITT) principles and included all subjects with a baseline and a postbaseline measurement. Some researchers may not regard this as a real ITT population, although the analyses were compliant with the ITT principle: data were analyzed by the group to which a subject was assigned by random allocation, even if the subject did not take the assigned treatment or otherwise did not follow the protocol. This issue is of special relevance when observing that the number of patients lacking at least 1 postbaseline urinary diary (but not I-QOL or PGI-I instruments) is consistently higher in the active treatment group than in the placebo group in all 3 clinical trials. This was because duloxetine patients with early intolerance to the drug did not complete diaries and were excluded from the primary IEF analysis.

These studies represent an overall benefit/risk analysis for duloxetine because they assessed the most obvious benefit (reduction in incontinence) and the most important risk (bothersome adverse events that prevent patients from continuing use of duloxetine). This analysis establishes a positive risk/benefit profile for the drug in the treatment of women with SUI.

Conclusion

In 3 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, patients receiving duloxetine had a statistically significant and clinically relevant reduction in the number of incontinence episodes and a corresponding improvement in quality of life. If this use of duloxetine is approved by the FDA (see sidebar, “Duloxetine and the FDA”), as it has been by the European regulatory agencies, it will be the first drug indicated for the treatment of SUI. This pharmacologic therapy is an additional option for women and is likely to become an integral component of patient management.

Main Points.

Surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI); however, success rates hover around 82%, and surgery is often not an option in elderly patients. Conservative therapies (biofeedback and behavior modification) frequently fail or are unsatisfactory for patients with severe SUI.

Results of animal studies highlight the importance of the pudendal nerve, middle urethra, and external urethral sphincter (EUS) in maintaining continence. By extension to humans, basic research suggests that the middle urethra and EUS could be a primary focus in the management of SUI.

The EUS helps to maintain continence by contracting to “guard” against the increased bladder pressure and thus prevent leakage. Serotonin and norepinephrine are 2 key neurotransmitters that stimulate the proximal end of the pudendal nerve to control the contraction of the EUS.

Duloxetine hydrochloride is a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. In animal studies, this agent produces an increase in nerve stimulation to the striated urethral sphincter muscle.

In each of 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, duloxetine-treated patients with SUI had a 50% or greater median decrease in incontinence episode frequency. Health-related quality-of-life scores were significantly improved with duloxetine compared with placebo in 2 of the 3 trials.

If the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves its use for SUI (as has already been done by European regulatory agencies), duloxetine will be the first drug indicated for the treatment of SUI in the United States.

References

- 1.Retzky SS, Rogers RM. Urinary incontinence in women. Clin Symp. 1995;47:2–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, et al. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158:875–880. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viktrup L, Bump RC. Simplified neurophysiology of the lower urinary tract. Prim Care Update Ob/Gyns. 2003;10:261–264. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JM, Bloom DA, McGuire EJ. The guarding reflex revisited. Br J Urol. 1997;80:940–945. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire EJ, Lytton B, Pepe V, Kohorn EI. Stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaivas JG, Olsson CA. Stress incontinence: classification and surgical approach. J Urol. 1988;139:727–731. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayigil O, Iftekhar AS, Metin A. The coexistence of intrinsic sphincter deficiency with type II stress incontinence. J Urol. 1999;162:1365–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidler H, Casper F, Thuroff JW. Role of striated sphincter muscle in urethral closure under stress conditions: an experimental study. Urol Int. 1987;42:195–200. doi: 10.1159/000281894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thuroff JW, Bazeed MA, Schmidt RA, Tanagho EA. Mechanisms of urinary continence: an animal model to study urethral responses to stress conditions. J Urol. 1982;127:1202–1206. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thuroff JW, Casper F, Heidler H. Pelvic floor stress response: reflex contraction with pressure transmission to the urethra. Urol Int. 1987;42:185–189. doi: 10.1159/000281892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamo I, Torimoto K, Chancellor MB, et al. Urethral closure mechanisms under sneeze-induced stress condition in rats: a new animal model for evaluation of stress urinary incontinence. Am J Phys Reg Integ Comp Phys. 2003;285:R356–R365. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamo I, Cannon TW, Conway DA, et al. The role of bladder-to-urethral reflexes in urinary continence mechanisms in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F434–F441. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00038.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JY, Cannon TW, Pruchnic R, et al. The effects of periuretral muscle-derived stem cell injection on leak point pressure in a rat model of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s00192-002-1004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thor KB, Katofiasc MA. Effects of duloxetine, a combined serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, on central neural control of lower urinary tract function in the chloraloseanesthetized female cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1014–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dmochowski RR, Miklos JR, Norton PA, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of North American women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003;170:1259–1263. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080708.87092.cc. [erratum in: J Urol. 2004;171:360] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Lange R, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of European and Canadian women with stress urinary incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;111:249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millard RJ, Moore K, Rencken R, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a four-continent randomized clinical trial. BJU Int. 2004;93:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]