Abstract

Community-based studies and surveys have found an association between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sexual dysfunction, in particular, erectile dysfunction (ED). The link between ED and LUTS has biologic plausibility. The following 4 theories have been used to explain how these disorders interrelate: 1) decreased or altered nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide levels in the prostate and penile smooth muscle; 2) autonomic hyperactivity effects on LUTS, prostate growth, and ED; 3) increased Rho-kinase activation/endothelin activity; and 4) prostate and penile atherosclerosis. The relationship of LUTS and sexual dysfunction suggests that treatment of one condition may impact the other.

Key words: Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Lower urinary tract symptoms, Sexual dysfunction, α-Blockers, Sildenafil

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sexual dysfunction are highly prevalent in aging men, and both conditions have a significant impact on overall quality of life. Previous consensus statements and other writings report that neither benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) nor LUTS, independent of age, adversely affect sexual function.1 Are men with LUTS/BPH at increased risk for sexual problems? Answering this question requires that sexual function be regarded as concerning more than just erectile function; rather, sexual function should be regarded as encompassing several different aspects or “domains.” Male sexual dysfunction may manifest as decreased libido, ejaculation dysfunction, erectile dysfunction (ED), or a combination of all 3 of these conditions. In addition, many currently available therapies for LUTS/BPH affect sexual function.

A causal association between LUTS and ED cannot be established on the basis of epidemiologic studies, of which there are an increasing number. Because of the restrictions necessary in clinical studies, causality is difficult to assign. Thus, the relationship between ED and LUTS should be reviewed according to a common set of criteria used by most epidemiologists to separate causal from noncausal explanations, as first proposed by Hill.2–4 This “causality method” attempts to establish a link by reviewing case-controlled reports, cohort studies, and general epidemiologic data, along with well-performed basic science investigations. Such reports should be examined for the strength of association (as measured by increases in the relative risk of ED with LUTS), the presence of a dose-response effect (ie, more LUTS equates with more severe ED), and a temporal relationship between the development of these disorders (disease progression). Most important, the observed epidemiologic data must have biologic plausibility and take into consideration alternative explanations (chance, bias, and confounding factors). The extent to which results from various studies are consistent with one another (replication of findings) is also an important component for establishing causality.

New data have emerged to indicate potential links among epidemiologic, physiologic, pathophysiologic, and treatment aspects of sexual dysfunction and LUTS. Each of these areas of research offers potential opportunities and challenges. An association between BPH/LUTS and sexual dysfunction that is more than coincidental may have implications in the clinical management of these disorders, as well as in the development of treatment guidelines. For example, treatment of one condition might have an impact on the other. In addition, there are specific drug interaction issues (eg, α-blockers and phosphodiesterase [PDE]-5 inhibitors) that warrant special attention.

Even if such an association were found to be present, however, the question remains as to why urologists should worry about sexual dysfunction in men with LUTS. The relationship between the 2 entities is important for several reasons: 1) additional information on risk factors for either condition could be important for patient screening; 2) there is an increasing pool of affected men, given the age demographics in many Western societies; 3) sexual problems related to LUTS are not necessarily limited to ED; and 4) many currently available LUTS treatments (medical and surgical) affect sexual function.

Epidemiology of LUTS Secondary to BPH and Sexual Dysfunction

Age is one of the most important risk factors for ED. Compared with men in their forties, men in their fifties and sixties have 2-fold and 5-fold increases, respectively, in the relative risk of ED.5 Overall, 52% of men aged 40 to 70 years have some degree of ED, and two thirds of these men have moderate to severe symptoms.6 A recent investigation found complete ED in 13% of men aged 55 to 70 years.7 Braun and colleagues8 reported a community-based survey of more than 4800 men assessing sexual activity, sexual satisfaction, and ED. The investigators found the prevalence of ED to increase with age, rising from 2.3% among men younger than 40 years to 53.4% among men older than 70 years, with progressive increases in every decade (mean age, 51.8 years; range, 30–80 years).

Data regarding clinically important aspects of the natural history of BPH center on the age-related development and course of anatomic changes in the prostate and of BPH-induced dysfunctional voiding symptoms, as well as pathophysiologic functional changes in the bladder and/or upper urinary tract. The prevalence of histologic BPH increases progressively from the fourth (8%) through the eighth (82%) decade of life.9 The prevalence of gross, potentially clinically significant BPH lesions shares this association with increasing age. For example, an autopsy study disclosed prevalences of histologically confirmed BPH in prostates with gross enlargement of 14%, 37%, and 39%, respectively, in men aged 50 to 59, 60 to 69, and older than 70 years10; these prevalences paralleled those of findings of a palpably enlarged prostate on rectal examination in 6975 men evaluated for life insurance.11 Limited reported data correlating autopsy prostate weight and histology have revealed that prostate weights exceed the 18-g mean normal weight by 50% or more in 61% of men aged 61 to 70 years, compared with 18% of men aged 51 to 60 years.12

In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which included 1057 men, the cumulative prevalence of a history/physical examination-based diagnosis of LUTS or BPH voiding dysfunction increased progressively from 26% to 79% from the fifth to eighth decades of life13; in the Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study, this diagnosis was recorded in 78% of the 2049 healthy volunteers by age 80 years.14 As contrasted with cumulative prevalence, prevalences of LUTS in 2110 men in Olmsted County, Minn, were found to be 26%, 33%, 41%, and 46% in men aged 40 to 49, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, and older than 70 years, respectively.15 An unequivocal role of BPH in the LUTS data should be viewed with caution for the following reasons: 1) although symptom scores and some symptoms show an increasing prevalence with advancing age, individual subjects show a disturbing tendency to have variably present and absent symptoms16; and 2) several studies have documented a comparable prevalence of similar symptoms in aging women.12,17

The question of whether men with LUTS/BPH are at increased risk for sexual problems was addressed by an interesting investigation with the use of a community-based survey.18 In this early 1990s study, approximately 2000 men, aged 50 to 80 years, underwent a questionnaire-based evaluation. Sexual satisfaction negatively correlated with increasing age and LUTS. In addition, urinary symptoms adversely affected the men’s general sense of well-being and self-esteem (ie, perception of sexual life satisfaction). The relative risk of sexual dissatisfaction stratified by the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ranged from 1.0 with an IPSS of 0 to 3.3 with an IPSS greater than 19 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Urinary Symptoms and Sexual Life Satisfaction

| Odds of Being | ||

|---|---|---|

| IPSS Score | Neutral | Dissatisfied |

| 0 | Reference | - |

| 1–7 | 1.50 (1.09–2.05) | 1.29 (0.75–2.21) |

| 8–19 | 2.07 (1.25–3.07) | 2.19 (1.13–4.23) |

| >19 | 2.38 (0.70–8.08) | 3.34 (0.79–14.12) |

Data from Macfarlane GJ et al. J Clin Epidemiol.1996;49:1171–1176.18

IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score.

In the Cologne Male Survey, Braun and colleagues8 assessed the epidemiology of ED in Germany and the proportion of men in need of medical treatment because of increased suffering from sexual dysfunction. Using a community-based survey of more than 4000 men, the investigators noted regular sexual activity in 96.0% of subjects in the youngest age group (30–39 years) and 71.3% of subjects in the oldest age group (70–80 years). The overall prevalence of ED was 19.2%, with a steep age-related increase (2.3%–53.4%) and a high comorbidity with hypertension, diabetes, pelvic surgery, and LUTS.

The Krimpen study of erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction assessed the relative risk of ED in a community cohort based on various clinical attributes.19 In this study, LUTS had a linear relationship with increasing risk of ED. The authors noted an increased relative risk of ED from 1.8 to 7.5, depending on the degree of urinary complaints, which was greater than the relative risk found with cardiac symptoms, pulmonary problems, or a history of smoking (Table 2). These results suggest that ED is a worthwhile symptom to ask about in patients who present with LUTS.

Table 2.

The Krimpen Study: Risk Factors for Erectile Dysfunction

| Adjusted | |

|---|---|

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio |

| Age 55–78 y | 2.3–14.3 |

| BMI>30 | 3.0 |

| LUTS | 1.8–7.5 |

| Cardiac symptoms | 2.5 |

| COPD | 1.9 |

| Smoking | 1.6 |

Data from Blanker MH etal. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:436–442.19

BMI, body mass index; LUTS, lower urinary , tract symptoms; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The association of ED with LUTS was also confirmed in 2 recent community-based studies. Nicolosi and colleagues20 sampled a random group of approximately 2400 men, aged 40 to 70 years, with a standardized questionnaire. The age-adjusted prevalence of moderate or complete ED was 34% in Japan, 22% in Malaysia, 17% in Italy, and 15% in Brazil. Increased risk of ED was associated with LUTS as well as with other, more-established risk factors. Similarly, in a cross-sectional, population-based, household survey, Moreira and colleagues21 noted an age-adjusted prevalence of ED of 39.5% (minimal, 25.1%; moderate, 13.1%; severe, 1.3%). Having never been married, diabetes, depression, and LUTS were significantly (P < .05) associated with an increased prevalence of ED.

It is well known that LUTS diminishes patient quality of life. Girman and colleagues22 reported a similar linear relationship between LUTS and the Bother Index. The investigators also demonstrated that interference with daily activities and decline in overall general health were directly related to worsening LUTS. Of note, sexual satisfaction was also significantly associated with LUTS; that is, the greater the severity of LUTS, the more likely that poor sexual satisfaction was reported. In a follow-up report, Girman and colleagues23 demonstrated a similar relationship between prostate volume and sexual dissatisfaction.

Most recently, Rosen and colleagues24 reported results from the Multinational Survey of the Aging Male (MSAM-7). This important study revealed a strong association between the frequency of sexual intercourse and patient IPSS score. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) score was also significantly associated with LUTS severity. Of importance, the association between LUTS and sexual dysfunction persisted after controlling for age and other comorbidities known to impact sexual function. Measures of ejaculatory dysfunction, reduced ejaculate, and ejaculation pain were also strongly associated with LUTS. The results of the MSAM-7 suggest that the majority of older men have active sex lives and that the severity of LUTS is an independent risk factor for sexual disorders, independent of other risk factors. The bother associated with sexual dysfunction in the aging male was confirmed by Vallancien and colleagues,25 who noted that ED and reduced ejaculation were highly prevalent in men with LUTS and strongly related to increasing age and LUTS severity.

The National Institutes of Health-sponsored Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial examined the effects of finasteride and/or doxazosin on BPH progression. Results of the study were reported at the 2002 convention of the American Urological Association (AUA). A secondary aim of this important study was to assess the relationship between sexual function and LUTS severity in 3000 men. McVary and colleagues26 examined the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and LUTS in a cross-sectional analysis of baseline MTOPS data and reported a strong association between baseline AUA symptom score and the various domains of sexual function, including libido, erectile capability, ejaculation, problem assessment, and overall satisfaction with sexual life (P < .001 for each domain). The investigators also found a significant association between the sexual function domains and peak urinary flow (P < .001). This latest report is important because the comorbidities that are frequently associated with ED (including hypertension, lipid disorders, diabetes) were controlled in a multivariate analysis and the patients were exceedingly well characterized clinically. In addition, the duration of LUTS was strongly associated with erectile function, problem assessment, and overall satisfaction with sexual life (P < .01). These results support an association between LUTS and sexual dysfunction that is independent of the usual comorbidities.

Mechanism of Interaction Between ED and LUTS

If there is an epidemiologic link between ED and LUTS, this relationship must have biologic plausibility. What are the possible interrelationships between these 2 entities? Possible explanations fall into 4 categories or theories, each with varying amounts of supporting data.

Nitric Oxide Synthase/Nitric Oxide Levels Decreased or Altered in the Prostate and Penile Smooth Muscle

This hypothesis attempts to explain the link between ED and LUTS by a proposed reduced production of nitrinergic innervation and nitric oxide synthase (NOS)/nitric oxide (NO) in the pelvis, including both the penis and the prostate. The theory closely follows that explaining the molecular mechanism of ED and links these 2 diseases into a single unifying concept. It is known that NOS/NO production in the prostate is reduced in BPH (transition zone) compared with normal prostate tissue. It logically follows that prostate tissue levels of NOS/NO are decreased in BPH progression, which reduces prostatic tone relaxation. This proposed reduction in NOS isoforms results in an altered neurogenic influence on voiding function that is recognized as progressive BPH or LUTS.

This theory is supported by limited evidence, in which nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase staining and neuronal NOS immunohistochemistry of BPH tissue show a qualitative decrease in the otherwise dense nitrinergic innervation of glandular epithelium, fibromuscular stroma, and blood vessels. Unlike the well-developed penile model, the role of NOS and its products are not well characterized in the prostate. The hypothesis is based on a limited number of studies that depend largely on immunohistochemistry. There are several methodologic flaws with these data, but the concept does have a consistent appeal.27,28

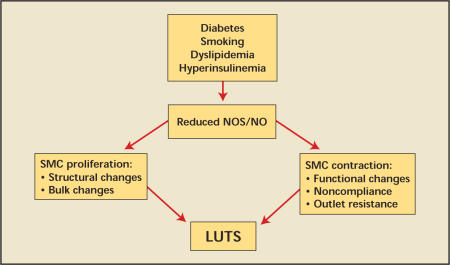

The NOS/NO theory of LUTS and ED was further supported by the characterization and functional relevance of cyclic nucleotide PDE isoenzymes of the human prostate.29 The most common PDEs noted in prostate tissue were PDE-4 and PDE-5. The functional relevance of these PDE isoenzymes is noted in the relaxing effect of non-specific PDE inhibitors (papaverine), as well as in the effect of specific PDE inhibitors (sildenafil). Of more interest for this review is the study by Fawcett and colleagues,30 in which Northern and ribonucleic acid dot blots for PDE-11A gene expression demonstrated its presence in the testes, skeletal muscle, and the prostate. PDE-11A protein abundance was greatest in the prostate compared with the other organs. These data, combined with in-vitro models that demonstrate an antiproliferative effect on human prostatic smooth muscle cells by NO donors (sodium nitroprusside), increased cell proliferation with NO antagonists, and a negative effect on the proliferation signal transduction pathway (protein kinase C) with sodium nitroprusside, give credence to the NOS/NO theory of ED and LUTS (Figure 1).31

Figure 1.

The nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide (NOS/NO) theory of erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). SMC, smooth muscle cell.

Autonomic Hyperactivity Effects on LUTS, Prostate Growth, and ED

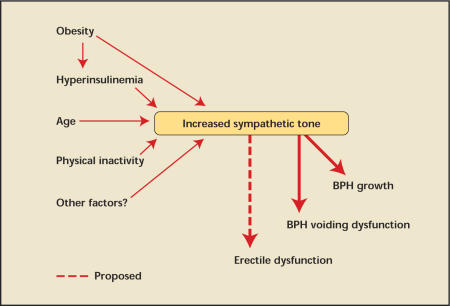

McVary and colleagues32 demonstrated that autonomic neural input to the prostate provided an environment that induced rat prostatic growth; absence of this input resulted in regression of the gland. These findings were supported by additional animal studies using a strain of rats (spontaneously hypertensive rats) that develop increased autonomic activity, prostate hyperplasia, and ED.33–35 The improvement in erectile function after brief aggressive treatment might be related to improvement in structurally based vascular resistance within the penis and the decrease in responsiveness of α1-adrenoceptor-mediated erectolytic signaling. This putative explanation is attractive because it links established clinical physiologic findings of LUTS, BPH, and ED with an established basic science support (Figure 2). It remains unclear whether the increase in LUTS or ED is the result of a central increase in sensitivity to peripheral signals or a consequence of an alteration in the function of the bladder/penis itself that generates increased central activation.

Figure 2.

Proposed theory of autonomic hyperactivity of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and erectile dysfunction (ED). Increased autonomic hyperactivity results from increased body mass index, hyperinsulinemia, increased age, and decreased physical activity. This increased sympathetic tone affects benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) growth, LUTS, and vasoconstrictive forces, resulting in ED. Adapted from McVary KT, Rademaker A, Lloyd GL, Gann P. Autonomic nervous system overactivity in men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005. In press. McVary KT, McKenna KE. The relationship between erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms: epidemiological, clinical, and basic science evidence. Curr Urol Rep. 2004 Aug;5(4):251–257.

The various animal models suggesting a role between autonomic nervous system (ANS) overactivity and increased prostate growth is further supported by epidemiologic investigations linking the clinical diagnosis of BPH with increased autonomic tone.14 Autonomic hyperactivity or increased ANS activity is significantly associated with the signs and symptoms of BPH. This association has implications for understanding the pathophysiology of BPH, prostate growth, ED, and BPH progression. The ANS is well known to be intimately involved in the mechanisms of voiding. Lloyd and McVary36 described the quantitative relationship between ANS tone and the subjective experience of dysfunctional voiding. The ANS translates “mood” into objective physiology (eg, fear leads to dry mouth and tachycardia). This suggests that the ANS acts as a mediator that can modulate voiding symptoms and/or ED around their anatomically designated baselines, perhaps in part under the influence of central, mood-related factors. Similarly, autonomic hyperactivity or increased sympathetic tone is a known regulator of smooth muscle relaxation and penile reactivity.

Alternate Pathway Mechanism: Rho-Kinase Activation/Endothelin Activity

Several investigators have suggested that the so-called “alternate pathways” of smooth muscle relaxation and contraction might be responsible for the relationship between ED and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). Chang and colleagues37 reported that corpus cavernosum smooth muscle from rabbits with partial bladder outlet obstruction showed a broad range of molecular and functional differences compared with controls. These changes included increased penile smooth muscle cell contractility, reduced relaxation, modest alterations in total smooth muscle myosin, decreased innervation, and increased smooth muscle bundle size. Although it is not entirely clear whether this putative mechanism is causative or even exclusive of the above-mentioned possibilities, its inclusion here for discussion purposes is well justified.

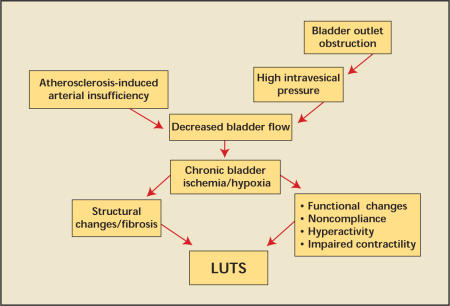

Pelvic Atherosclerosis

An additional theory relating to both ED and LUTS involves diffuse atherosclerosis of the prostate, penis, and bladder.38 Major risk factors for atherosclerosis include hypertension, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes. Animal models mimicking pelvic ischemia and hypercholesterolemia show a striking similarity in the smooth muscle alterations of the detrusor and corporal smooth muscle. There are several potential mechanisms for these alterations, including hypoxia-induced overexpression of transforming growth factor ß1 and altered prostanoid production.

The concept that these mechanisms could adversely affect penile smooth muscle function is consistent with our current understanding of the penile pro-erectile response. The relevant mechanism explaining the bladder effects might be similar, with an associated bladder ischemia (BOO or pelvic vascular disease) inducing the same smooth muscle loss, with replacement of collagen deposition and fibrosis, as well as loss of compliance, hyperactivity, and impaired contractility (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Atherosclerosis of the bladder/erectile dysfunction model. LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms.

Impact of ED and Drug Tolerability

Several studies have attempted to assess the relationship between ED and LUTS by treating one disorder and measuring the impact on the other. In a study by Sairam and colleagues,39 men in a clinical practice complaining of both ED and LUTS received sildenafil therapy. Results showed that a lower IPSS at baseline was predictive of a better response to ED therapy with sildenafil. In addition, treatment with sildenafil appeared to improve urinary symptom scores. Of interest, the investigators reported no relationship between ED and LUTS. Whether this relates to a more moderate sample size or other unrecognized factors is not known. In a similar vein, Hopps and colleagues40 reported mild improvements in symptoms of BPH/LUTS (IPSS changes) in association with on-demand PDE-5 therapy (sildenafil) for ED in men with concomitant BPH/LUTS. Although this pilot study was neither blinded nor placebo-controlled, the results suggest a common mechanism and/or therapy for this LUTS-ED symptom complex. Clearly, a well-designed and controlled study is mandatory to further elucidate the relationship between these 2 important disorders.

What is the impact of α-blockers on erectile function? Theoretically, α-blockers might contribute to the improvement of ED through α-adrenergic mechanisms that may cause alterations in the balance of penile vasoconstrictive and vasorelaxant forces that favor pro-erectile mechanisms. Conversely, α1-blockers with excessive hypotensive effects might produce anti-erectile effects by reducing penile filling pressure. Oral α-receptor antagonists exert their effects by blocking the actions of norepinephrine at α1-adrenoceptors on cavernosal smooth muscle cells. Norepinephrine released from sympathetic nerve terminals ordinarily acts at postjunctional α1-receptors to produce smooth muscle contraction and detumescence. This neurotransmitter also acts at presynaptic α2-receptors on the ends of nerve terminals to reduce norepinephrine release. Given their selectivity profile, the α-blockers used for the treatment of LUTS are not likely to affect the presynaptic α2-receptors.41

There are few reports detailing the impact of α-blocker use on ED improvement. Lukacs and colleagues42 reported that, in patients with BPH who received alfuzosin, self-perceived sense of sexual satisfaction was significantly improved from baseline, with the degree of improvement correlating with age. The biggest improvement was noted in middle-aged men with moderate to severe LUTS at baseline. In a similar study, the effect of once-daily alfuzosin (10 mg) on sexual functioning was prospectively assessed in 838 men at baseline and after 1 year of treatment.43 Comparison of mean weighted scores on the Danish Prostate Symptom Score sexual function questionnaire showed improvement in the erectile function domain by 36% over baseline (baseline 2.5 [SD, 2.2] decreased 0.9 [SD, 2.0]; P < .001). Improvement was most marked in those with the most severe LUTS.

Because α-blockers may have beneficial effects in patients with ED, Kaplan and colleagues44 investigated the synergistic effects of doxazosin and intracavernosal injection (ICI) therapy in patients for whom ICI therapy alone failed to induce an erection. Overall, 22 (57.9%) of 38 patients with the combined regimen had a significant therapeutic response (>60% IIEF improvement). The synergistic effects of vascular dilation and blockade of sympathetic inhibition is one explanation for this response.

What are the adverse effects of α-blockers on sexual function? In one large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the incidences of abnormal ejaculation attributable to tamsulosin, 0.4 mg and 0.8 mg daily, were 8.4% and 18.1%, respectively. No subjects discontinued therapy because of this adverse effect.45

However, the only meaningful way to compare the tolerabilities of different α-blockers is with randomized comparison trials. In one such randomized study comparing alfuzosin and tamsulosin, the incidence of any ejaculatory disturbance was less than 3% in both groups.46 Another unpublished study failed to show any significant differences among alfuzosin, tamsulosin, and placebo in the incidence of ejaculatory disturbance (data on file, Sanofi-Synthelabo Inc, New York).

With the exception of tamsulosin, the reported incidence of ejaculatory dysfunction associated with α-blockers is low. This is demonstrated by the results of the MTOPS study, in which the α-blocker arm had few sexual dysfunction adverse effects (see Table 2 of Dr. Roehrborn’s article in this supplement).47 The incidence of erectile dysfunction or abnormal ejaculation with other α-blockers seems to be negligible.

Conclusion

LUTS and sexual dysfunction are highly prevalent in aging men and have a significant impact on overall quality of life. New data have emerged to indicate potential links among epidemiologic, physiologic, pathophysiologic, and treatment aspects of these 2 entities.

Over the past 8 years, numerous studies have provided community-based and clinically based data that suggest a strong and consistent association between LUTS and ED. This association is supported by the consistent linear relationship of more severe LUTS with more severe ED. The relationship is further supported by a significant association among LUTS, sexual satisfaction, and prostate volume.

The link between ED and LUTS has biologic plausibility, given the 4 leading theories of how these disorders interrelate: 1) decreased or altered NOS/NO levels in the prostate and penile smooth muscle; 2) autonomic hyperactivity effects on LUTS, prostate growth, and ED; 3) increased Rho-kinase activation/ endothelin activity; and 4) prostate and penile atherosclerosis. Each of these theories is supported by varying amounts of data.

Several studies have attempted to assess the relationship between ED and LUTS by treating one disorder and measuring the impact on the other. The positive outcomes seen, regardless of which disease is treated primarily, suggest a common etiology or mechanism for the 2 disorders. The patient bother attributable to this effect is less clear. In general, α1-blockers are associated with a low rate of sexual dysfunction.

Main Points.

Several studies have found associations between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sexual dysfunction. Results of the Multinational Survey of the Aging Male suggest that older men have active sex lives and that the severity of LUTS has an impact on sexual disorders independent of other risk factors.

One finding of the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms trial was a strong association between baseline American Urological Association symptom score and the various domains of sexual function, including libido, erectile capability, ejaculation, problem assessment, and overall satisfaction with sexual life.

One hypothesis to explain the link between erectile dysfunction (ED) and LUTS proposes a reduced production of nitrinergic innervation and nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide in the pelvis, including both the penis and the prostate.

Research suggests that the autonomic nervous system acts as a mediator that can modulate voiding symptoms and/or ED around their anatomically designated baselines, perhaps in part under the influence of central, mood-related factors.

Several investigators have suggested that the so-called “alternate pathways” of smooth muscle relaxation and contraction might be responsible for the relationship between ED and bladder outlet obstruction.

An additional theory relating to both ED and LUTS is diffuse atherosclerosis of the prostate, penis, and bladder.

References

- 1.McConnell JD, Barry MJ, Bruskewitz RC, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 8: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1994. AHCPR publication 94-0582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association and causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McVary KT, Carrier S, Wessells H. Smoking and erectile dysfunction: evidence based analysis. J Urol. 2001;166:1624–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, authors. The Health Consequences of Smoking-Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Bethesda, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson CC, West SL, Glasser DB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of ED in a US population-based sample: phase I results. Presented at: American Urological Association 96th Annual Meeting; June 2–7, 2001; Anaheim, Calif.. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, et al. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green JSA, Holden STR, Bose P, et al. An investigation into the relatonship between prostate size, peak urinary flow rate and male erectile function. Int J Impot Res. 2001;13:322–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun M, Wassmer G, Klotz T, et al. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction: results of the ‘Cologne Male Survey’. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12:305–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, et al. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984;132:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robson MC. The incidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic carcinoma in cirrhosis of the liver. J Urol. 1964;92:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lytton B. Interracial incidence of benign prostatic hypertrophy. In: Hinman F, editor. Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grayhack JT. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: the scope of the problem. Cancer. 1992;70(1 suppl):275–279. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<275::aid-cncr2820701314>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guess HM, Arrighi HM, Metter EJ, et al. Cumulative prevalence of prostatism matches the autopsy prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 1990;17:241–246. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glynn RJ, Campion EW, Bouchard GR, et al. The development of benign prostatic hyperplasia among volunteers in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:78–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chute CG, Panser LA, Girman CJ, et al. The prevalence of prostatism: a population-based survey of urinary symptoms. J Urol. 1993;150:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrighi HM, Guess HA, Metter EJ, et al. Symptoms and signs of prostatism as risk factors for prostatectomy. Prostate. 1990;16:253–261. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chai TC, Belville WD, McGuire EJ, et al. Specificity of the American Urological Association voiding symptom index: comparison of unselected and selected samples of both sexes. J Urol. 1993;150:1710–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macfarlane GJ, Botto H, Sagnier PP, et al. The relationship between sexual life and urinary condition in the French community. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1171–1176. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanker MH, Bohnen AM, Groeneveld FP, et al. Correlates for erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction in older Dutch men: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:436–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Jr, Shirai M, et al. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2003;61:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreira ED, Jr, Lisboa Lobo CF, Villa M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction in Salvador, northeastern Brazil: a population-based study. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14(suppl 2):S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto T, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in four countries. Urology. 1998;51:428–436. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Rhodes T, et al. Association of health-related quality of life and benign prostatic enlargement. Eur Urol. 1999;35:277–284. doi: 10.1159/000019861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen R, Altwein J, Boyle P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction: the Multinational Survey of the Aging Male (MSAM-7) Eur Urol. 2003;44:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallancien G, Emberton M, Harving N, et al. Sexual dysfunction in 1,274 European men suffering from lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2003;169:2257–2261. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067940.76090.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McVary KT, Foster H, Kusek J, et al. Self-reported sexual function in men with symptoms of BPH—a MTOPS Study report [abstract] Int J Impot Res. 2002;14(suppl 3):S59–S60. Abstract CP1.32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloch W, Klotz T, Loch C, et al. Distribution of nitric oxide synthase implies a regulation of circulation, smooth muscle tone, and secretory function in the human prostate by nitric oxide. Prostate. 1997;33:1–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970915)33:1<1::aid-pros1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klotz T, Bloch W, Loch C, et al. Pattern of distribution of constitutive isoforms of NO synthase in the normal prostate and obstructive prostatic hyperplasia [in German] Urology. 1997;36:318–322. doi: 10.1007/s001200050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uckert S, Kuthe A, Jonas U, Stief CG. Characterization and functional relevance of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isoenzymes of the human prostate. J Urol. 2001;166:2484–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fawcett L, Baxendale R, Stacey P, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a distinct human phosphodiesterase gene family: PDE11A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3702–3707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050585197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guh JH, Hwang TL, Ko FN, et al. Antiproliferative effect in human prostatic smooth muscle cells by nitric oxide donor. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:467–474. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McVary KT, Razzaq A, Lee C, et al. Growth of the rat prostate gland is facilitated by the autonomic nervous system. Biol Reprod. 1994;51:99–107. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golomb E, Rosenzweig N, Ellam R, et al. Spontaneous hyperplasia of the ventral lobe of the prostate in aging genetically hypertensive rats. J Androl. 2000;21:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong YC, Hung YC, Lin SN, et al. The norepinephrine tissue concentration and neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity in genitourinary organs of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1996;56:215–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale TM, Okabe H, Bushfield TL, et al. Recovery of erectile function after brief aggressive antihypertensive therapy. J Urol. 2002;168:348–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lloyd GL, McVary KT. The role of autonomic nervous system tone in BPH symptomatology [abstract] J Urol. 2002;167:214. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang S, Hypolite JA, Zderic SA, et al. Enhanced force generation by corpus cavernosum smooth muscle in rabbits with partial bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2002;167:2636–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarcan T, Azadzoi KM, Siroky MB, et al. Age related erectile and voiding dysfunction: the role of arterial insufficiency. Br J Urol. 1998;82(suppl 1):26–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.0820s1026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sairam K, Kulinskaya E, McNicholas TA, et al. Sildenafil influences lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int. 2002;90:836–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopps CV, Mulhall JP. Assessment of the impact of sildenafil citrate on lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men with erectile dysfunction (ED) [abstract] J Urol. 2003;169(4 suppl):375. Abstract 1401. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyllie MG, Andersson KE. Orally active agents: the potential of alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists. In: Carson CD, Kirby RS, Goldstein I, editors. Textbook of Erectile Dysfunction. Oxford: Isis Medical Media; 1999. pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lukacs B, Leplege A, Thibault P, Jardin A. Prospective study of men with clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia treated with alfuzosin by general practitioners: 1-year results. Urology. 1996;48:731–740. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Moorselaar P, Emberton M, Harving N, et al. Alfuzosin 10mg once daily improves sexual function in men with LUTS and concomitant sexual dysfunction [abstract] J Urol. 2003;169:478. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan SA, Reis RB, Kohn IJ, et al. Combination therapy using oral alpha-blockers and intracavernosal injection in men with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1998;52:739–743. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamsulosin [package insert] Ridgefield, Conn: Boehringer Ingelheim; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buzelin JM, Fonteyne E, Kontturi M, et al. Comparison of tamsulosin with alfuzosin in the treatment of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction (symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia) Br J Urol. 1997;80:597–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effects of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]