Abstract

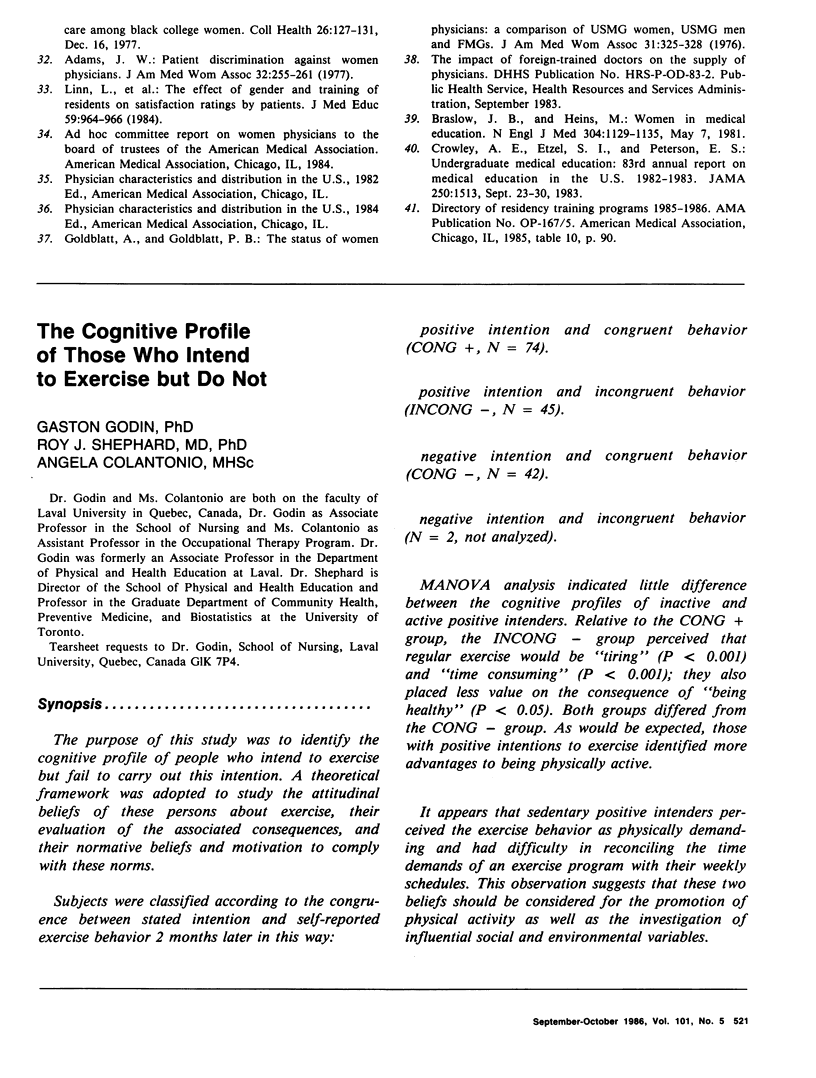

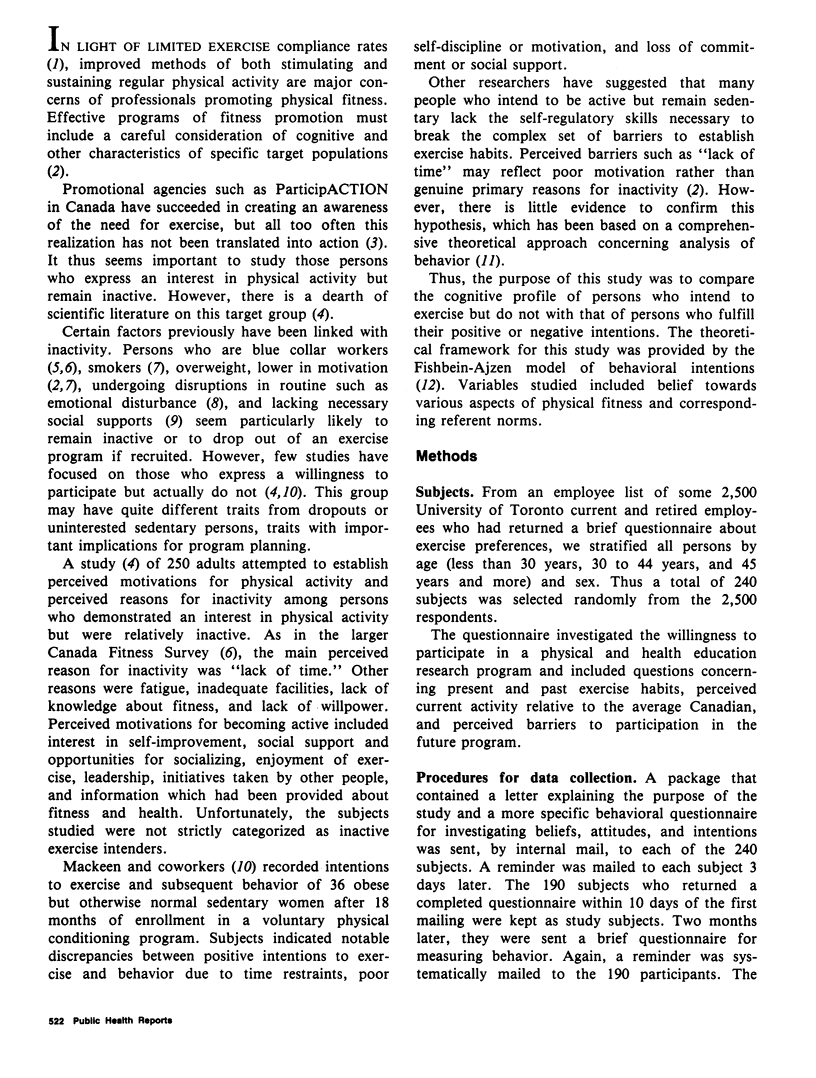

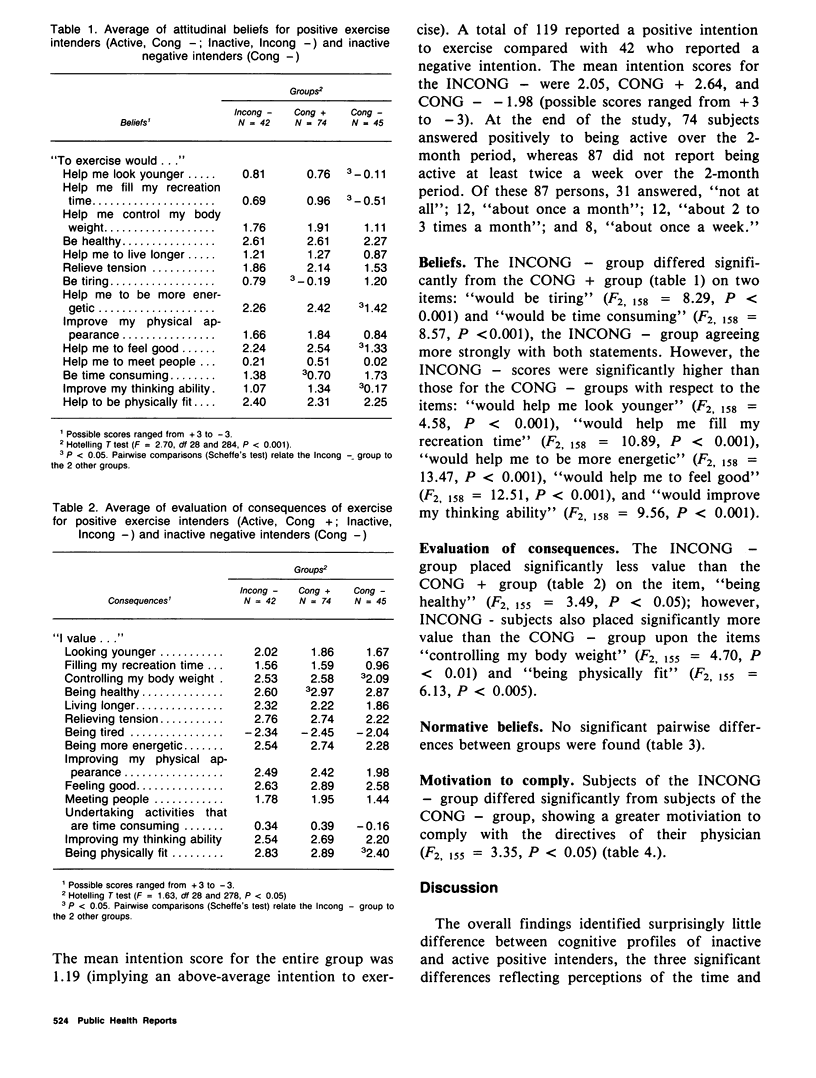

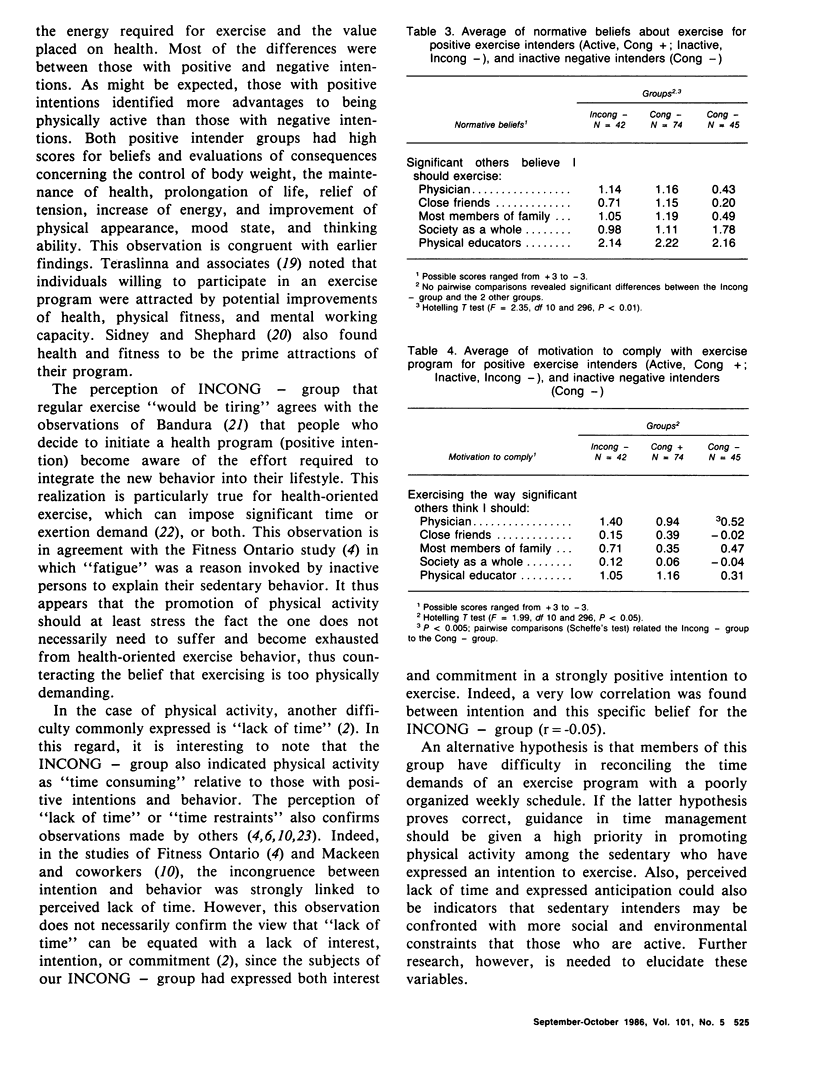

The purpose of this study was to identify the cognitive profile of people who intend to exercise but fail to carry out this intention. A theoretical framework was adopted to study the attitudinal beliefs of these persons about exercise, their evaluation of the associated consequences, and their normative beliefs and motivation to comply with these norms. Subjects were classified according to the congruence between stated intention and self-reported exercise behavior 2 months later in this way: positive intention and congruent behavior (CONG+, N = 74). positive intention and incongruent behavior (INCONG-, N = 45). negative intention and congruent behavior (CONG-, N = 42). negative intention and incongruent behavior (N = 2, not analyzed). MANOVA analysis indicated little difference between the cognitive profiles of inactive and active positive intenders. Relative to the CONG+ group, the INCONG- group perceived that regular exercise would be "tiring" (P less than 0.001) and "time consuming" (P less than 0.001); they also placed less value on the consequence of "being healthy" (P less than 0.05). Both groups differed from the CONG- group. As would be expected, those with positive intentions to exercise identified more advantages to being physically active. It appears that sedentary positive intenders perceived the exercise behavior as physically demanding and had difficulty in reconciling the time demands of an exercise program with their weekly schedules. This observation suggests that these two beliefs should be considered for the promotion of physical activity as well as the investigation of influential social and environmental variables.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977 Mar;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman R. K., Sallis J. F., Orenstein D. R. The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Rep. 1985 Mar-Apr;100(2):158–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G., Shephard R. J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985 Sep;10(3):141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G., Shephard R. J. Physical fitness promotion programmes: effectiveness in modifying exercise behaviour. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1983 Jun;8(2):104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKeen P. C., Franklin B. A., Nicholas W. C., Buskirk E. R. Body composition, physical work capacity and physical activity habits at 18-month follow-up of middle-aged women participating in an exercise intervention program. Int J Obes. 1983;7(1):61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie J. F., Shephard R. J. Physiological and psychological effects of training--a comparison of individual and gymnasium programs, with a characterization of the exercise "drop-out". Med Sci Sports. 1971 Fall;3(3):110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldridge N. B. Compliance and exercise in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a review. Prev Med. 1982 Jan;11(1):56–70. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(82)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney K. H., Shephard R. J. Attitudes towards health and physical activity in the elderly. Effects of a physical training program. Med Sci Sports. 1976 Winter;8(4):246–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk D. C., Rudy T. E., Salovey P. Health protection: attitudes and behaviors of LPNs, teachers, and college students. Health Psychol. 1984;3(3):189–210. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.3.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]