Abstract

Wound repair in horse limbs is often complicated by excessive fibroplasia and scarring. Occlusion of the microvessels populating the granulation tissue appears to be involved in the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix during the repair of limb wounds. This study aimed to determine whether endothelial cell hypertrophy or hyperplasia, or both, contribute to microvascular occlusion and whether the pericyte is involved in this anomaly. We created 5 wounds, each 2.5 × 2.5 cm, on both forelimbs and on the body of 6 horses. One limb was bandaged to stimulate excessive wound fibroplasia. Weekly biopsy specimens were evaluated by transmission electron microscopy to measure microvessel luminal diameters and the surface area of endothelial cells and to count endothelial cells and pericytes. Microvessels were occluded significantly more often in limb wounds than in body wounds. The surface area of endothelial cells lining occluded microvessels (mean ± standard error, 28.4013 ± 1.5154 μm2) was significantly greater (P = 0.05) than that of cells lining patent microvessels (26.2220 ± 1.5268 μm2). Conversely, neither the number of endothelial cells nor the number of pericytes differed between patent and occluded microvessels or between limb and body wounds. Furthermore, the wound location and the status of the microvessels (patent or occluded) did not alter the ratio of endothelial cells to pericytes. These data suggest that endothelial cell hypertrophy might play a role in the microvascular occlusion present in granulation tissue of limb wounds in horses, but the contribution of the pericyte remains obscure.

Résumé

La guérison de plaies appendiculaires chez le cheval est souvent compliquée par une fibroplasie abondante menant à une cicatrisation exagérée. Il appert qu’une occlusion des microvaisseaux peuplant le tissu de granulation soit liée à cette accumulation excessive de matrice extracellulaire. La présente étude visait à déterminer si une hypertrophie ou une hyperplasie des cellules endothéliales contribuait à l’occlusion microvasculaire, et si le péricyte participait à cette anomalie. Cinq plaies, mesurant 2.5 × 2.5 cm, ont été créées sur chacun des membres thoraciques ainsi que sur l’aspect latéral de la cage thoracique de 6 chevaux. Un membre fut mis sous bandage afin de stimuler la fibroplasie excessive. Des échantillons de bord de plaies furent prélevés à chaque semaine, pendant 6 semaines, et préparés pour la microscopie électronique par transmission. Le diamètre de la lumière des microvaisseaux ainsi que l’aire des cellules endothéliales furent mesurés, puis le nombre de cellules endothéliales et de péricytes fut déterminé. Les microvaisseaux présents dans les plaies appendiculaires étaient occlus significativement plus souvent que ceux de plaies corporelles. L’aire des cellules endothéliales tapissant ces microvaisseaux occlus (28.4013 ± 1.5154 μm2) était significativement plus grande (P = 0.05) que celle de cellules tapissant les microvaisseaux patents (26.2220 ± 1.5268 μm2). À l’inverse, le nombre de cellules endothéliales et de péricytes était semblable dans les microvaisseaux occlus et patents ainsi que dans les plaies appendiculaires et corporelles. De plus, ni l’emplacement de la plaie ni le statut des microvaisseaux n’altéraient le ratio cellules endothéliales:péricytes. Ces données suggèrent qu’une hypertrophie des cellules endothéliales contribue à l’occlusion microvasculaire présente au niveau du tissu de granulation de plaies appendiculaires chez le cheval, alors que le rôle du péricyte demeure obscur.

(Traduit par les auteurs)

Introduction

Wounds in horses must often heal by 2nd intention because of massive tissue loss and contamination (1). Although body wounds tend to repair uneventfully, exuberant granulation tissue (“proud flesh”) may develop in wounds located on the limb (2–4). Excessive fibroplasia then compromises wound contraction and epithelialization, leading to extensive scars. Since most horses are destined for athletic careers, problematic repair of limb wounds represents an important economic burden to the equine industry.

Deep traumatic wounds in people repair via a process of fibroplasia that initially takes place in an inflammatory environment and is characterized by marked angiogenesis. The outcome may be a hypertrophic scar or a keloid, particularly in black people (5). Despite the presence of numerous microvessels within the lesion, these tend to be occluded (6,7). Likewise, although the excessive granulation tissue that develops in limb wounds of horses contains numerous microvessels, we have recently shown that their lumens are obstructed significantly more often than those of equivalent vessels populating body wounds that heal normally (8). This occlusion may bring about a deficient oxygen gradient within the wound and, via up-regulation of angiogenic and fibrogenic cytokines (9), exacerbate angiogenesis and the production of collagen by dermal fibroblasts, a key feature of the aforementioned lesions (4,5,10).

Microvascular occlusion could result from endothelial cell hyperplasia (11) or hypertrophy, or both, and may be influenced by the surrounding pericyte. A major role of the pericyte is to shape a uniform vessel diameter. In postcapillary venules, the pericyte completely encircles and grips the endothelium, which may provide significant contractile function, exerted through both the tropomyosin and the alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) myofilaments within the pericyte (12). Indeed, capillary diameter has been shown to vary extensively in the absence of pericytes, both increased and decreased diameter being seen (13). Alternatively, pericytes may control capillary diameter via paracrine and cell-to-cell, contact-dependent regulation of endothelial proliferation and differentiation (14). Specifically, the absence of pericytes in embryos without platelet-derived growth factor B and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β coincides with endothelial hyperplasia and increased capillary diameter, which suggests that pericytes negatively control endothelial proliferation (13).

The overall aim of our research is to elucidate the pathogenesis of “proud flesh” in horses. In this study, we hypothesized that the extensive scars resulting from the development of exuberant granulation tissue in the limbs of horses may share a basis of development with human hypertrophic scars and keloids, in which microvascular occlusion prevails and may be related to the endothelial cell or the pericyte, or both (6). Specifically, we proposed that endothelial cell hypertrophy or hyperplasia may exist in the occluded microvessels populating the exuberant granulation tissue in limb wounds of horses, that the ratio of endothelial cells to pericytes may be altered, and that this alteration may contribute to the microvascular occlusion or to the abundant extracellular matrix developing within limb wounds in horses.

Materials and methods

Horses

Six healthy 2- to 3-y-old standardbred mares were used for the experiment, which complied with the Université de Montréal’s guidelines and was sanctioned by the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Prior to entry into the study, the horses were treated with a broad-spectrum anthelmintic and vaccinated against tetanus, Eastern and Western equine encephalomyelitis, influenza, and West Nile disease. The horses were kept in standing stalls for the duration of the study and allowed ad libitum access to grass hay and water. They were examined daily for signs of discomfort, lameness, systemic illness, and bandage slippage.

Surgical procedure

Each horse was sedated with detomidine hydrochloride, 0.01 mg/kg administered intravenously (IV) (Dormosedan; Pfizer Canada, Kirkland, Quebec), and butorphanol tartrate, 0.04 mg/kg IV (Torbugesic; Wyeth, Ville St-Laurent, Quebec), then the hair was clipped from the dorsolateral aspect of both metacarpi and 1 randomly chosen hemithorax. Local anesthesia was obtained with 2% lidocaine hydrochloride, 0.5 mg/kg administered subcutaneously (Lurocaïne; Vetoquinol, Lavaltrie, Quebec). A lateral high palmar nerve block was used to desensitize each metacarpus and an inverted L-block to desensitize the assigned hemithorax.

The surgical sites were aseptically prepared and 5 areas, each 2.5 × 2.5 cm, were traced, with the use of a sterile template, on the dorsolateral aspect of each metacarpus, beginning just above the fetlock, and on the lateral thoracic wall; the areas were 1.5 cm apart in a staggered vertical column. Full-thickness wounds were then created with a scalpel within the confines of the tracings and left to heal by 2nd intention. Excised skin from the lowermost wound was kept as a time-0 sample.

All horses had 1 randomly designated forelimb bandaged postoperatively with a nonadherent permeable dressing (Melolite; Smith-Nephew Canada, St-Lambert, Quebec) secured with 12-cm-wide sterile conforming gauze (Easifix; Smith-Nephew Canada) and then a cotton outer bandage, held in place with a 10-cm-wide rippable cohesive bandage (PowerFlex; Smith-Nephew Canada) and 1 turn of 7.6-cm-wide adhesive tape (Elastoplast; Smith-Nephew Canada) at either extremity, to induce the formation of exuberant granulation tissue and thus lead to scarring (15,16). Bandages were changed every 2 to 3 d until complete healing.

Biopsy samples

In each horse, biopsy was performed on 1 wound per site (thorax, unbandaged limb, and bandaged limb) at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 wk postoperatively. To avoid repeated trauma, each wound, beginning with the most distal one, was designated for only 1 biopsy. After sedation and local anesthesia were achieved as for the surgical procedure, full-thickness specimens were taken with an 8-mm-diameter biopsy punch, to include a 3- to 4-mm strip of peripheral skin, the migrating epithelium, and a 3- to 4-mm strip of granulation tissue when present (4,15).

Each sample was cut in half. The 1st half was quickly immersed in a cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution buffered with 0.05 M cacodylate, cut into 0.5-mm3 cubes with a sharp razor blade, and then fixed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The 2nd half was fixed in neutral-buffered 10% formalin and processed in paraffin blocks for another study, on apoptosis (8).

Transmission electron microscopy

The tissue cubes were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide and colored with 0.5% uranyl acetate. Samples were subsequently dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in propylene oxide/Epon (17). They were cut into thin (60-nm) sections, mounted on copper grids, stained with lead citrate, and examined with a Philips 300 transmission electron microscope (Royal Philips Electronics, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

Tissues were examined primarily for evaluation of the microvasculature. Only microvessels cut unambiguously in cross-section at the level of the nuclei of capillary endothelial cells and possessing no smooth muscle cells were used in the data collection. Microvessels were photographed at magnifications from 1500 to 7000×. The photographs were scanned and calibrated into pixels per micrometer and analyzed with the use of commercial image-processing software (Image J [Windows version of the National Institutes of Health image program]; Scion Corporation, Frederick, Maryland, USA). For each microvessel, endothelial cells and pericytes were counted, then the surface area of each endothelial cell was measured, in a blinded fashion, by 2 observers.

Statistical analyses

The weighted kappa coefficient was used to assess interobserver agreement; values of 0.4 and lower indicated poor agreement. A linear model with horse identification as a random factor was used to statistically analyze the mean surface area of endothelial cells as measured by TEM. A repeated-measures linear model with time and treatment as repeated factors was used to compare the number of endothelial cells populating the vascular wall. The logarithm of endothelial cell number was used to normalize this distribution. Poisson’s regression model with the individual horse treated as a random factor and the number of cells as the dependent variable was used to compare the number of pericytes. A repeated-measures linear model with time and treatment as repeated factors was used to assess the ratio of endothelial cells to pericytes. A priori contrasts were used to compare different levels of the independent variables. All analyses were carried out with SAS version 8.2 software (Cary, North Carolina, USA); a P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

As reported in a previous publication, granulation tissue became exuberant in all bandaged limb wounds approximately 1 wk postoperatively (8). Other wounds healed uneventfully, and “proud flesh” did not develop at any time during the study; granulation tissue was less abundant in the thoracic wounds. Microvessels were occluded significantly more often in limb wounds than in thoracic wounds, regardless of postoperative time (8).

A total of 234 electron micrographs of microvessels were deemed of adequate quality to be used for cell counts and measurements. There was excellent agreement between the 2 independent observers for all variables assessed (weighted kappa coefficient ≥ 0.9).

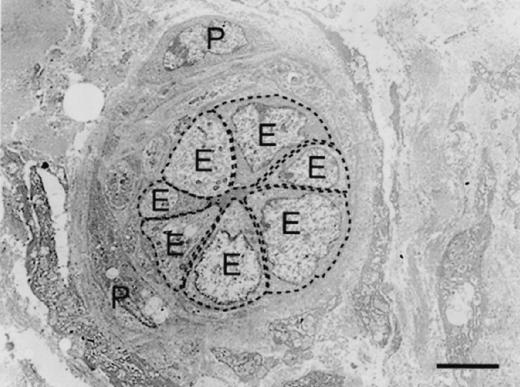

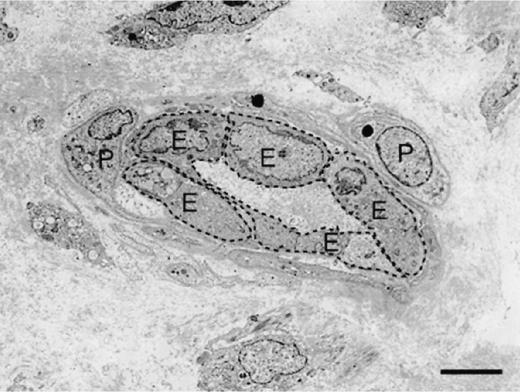

The surface area of endothelial cells lining occluded microvessels (mean ± standard error, 28.4013 ± 1.5154 μm2) was significantly greater (P = 0.05) than that of endothelial cells lining patent microvessels (26.2220 ± 1.5268 μm2), regardless of biopsy-sample origin or postoperative time (Figures 1 and 2). The enlarged endothelial cells were tightly packed and at times presented unusual cytoplasmic outpouchings that appeared to obstruct the vessel lumen.

Figure 1.

Transmission electron photomicrograph showing an occluded microvessel from an unbandaged forelimb wound 1 wk postoperatively. The enlarged endothelial cells (E) are tightly packed and at times present unusual cytoplasmic protrusions that appear to obstruct the vessel lumen. The broken line traces the periphery of an endothelial cell, such as was used to measure the surface area. P — pericyte. Bar — 5 μm.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron photomicrograph showing a patent microvessel from an unbandaged forelimb wound 3 wk postoperatively.

There was no effect of biopsy-sample origin (P = 0.44) or of microvessel status (P = 0.45) on the mean number of endothelial cells populating the vessel wall (3.7768 ± 1.4916 for occluded microvessels compared with 3.7788 ± 1.7715 for patent microvessels); however, endothelial cell hypoplasia was evident 2 and 3 wk postoperatively compared with what was observed in intact skin (P = 0.04), regardless of biopsy-sample origin (thoracic wound, bandaged limb wound, or unbandaged limb wound) or microvessel status (patent or occluded).

There was no effect of biopsy-sample origin (P = 0.54), postoperative time (P = 0.32), or microvessel status (P = 0.13) on the number of pericytes intimately associated with the vessel wall (1.3802 ± 1.0666 per occluded microvessel compared with 1.3628 ± 1.3029 per patent microvessel).

The ratios of endothelial cells to pericytes were similar regardless of biopsy-sample origin (P = 0.20), postoperative time (P = 0.09), or microvessel status (P = 0.51). They were 3.1849 ± 0.3158 for limb wounds, 2.8104 ± 0.2972 for thoracic wounds, and 3.3244 ± 0.3762 for intact skin.

Discussion

Although a number of publications have focused on the treatment of problematic wounds, the pathogenesis of exuberant granulation tissue in horses continues to elude us. We recently documented the presence of occluded microvessels within the granulation tissue of limb wounds in the horse (8) and surmised that this feature may lead to hypoxia, which might subsequently contribute to excessive collagen synthesis (9). The present study attempted to define the basis of the occlusion, as well as the relationship between the presence of endothelial cells and pericytes and an excessive amount of granulation tissue in horse wounds.

Our findings in this study suggest that endothelial cell hypertrophy may contribute to occlusion of the microvessels populating the granulation tissue of healing wounds. Indeed, as measured on electron micrographs, the mean surface area of endothelial cells lining occluded microvessels, regardless of their origin, significantly surpassed that of endothelial cells lining patent microvessels. Conversely, microvascular occlusion did not appear to result from endothelial cell hyperplasia, since the number of endothelial cells did not differ as a function of occlusion, although fewer cells were found lining the vessels of 2- and 3-wk-old granulation tissue compared with intact skin. This latter fact may relate to the relative immaturity of blood vessels at this stage of repair; more cells would be expected to populate the new vessel as angiogenesis progressed and the vessel matured. Although there were far more occluded microvessels within limb wounds than within thoracic wounds, and endothelial cell hypertrophy was a consistent feature of occluded microvessels, this latter characteristic could not be related to the origin of the wound (thoracic versus unbandaged limb versus bandaged limb).

It has been reported that endothelial cells are more crowded in cerebral microvessels of mice harboring deletion of the PDGF-B and PDGFR-β genes, a condition leading to pericyte deficiency and endothelial hyperplasia or hypertrophy (13). The authors noted luminal membrane folding as a result of the greater number or size of the endothelial cells, which could lead to luminal occlusion of the microvessel. Although we did not observe such folding, the enlarged endothelial cells were tightly packed and at times presented unusual cytoplasmic outpouchings that appeared to obstruct the lumen.

Lumen-filling endothelial cells in rats with severe angioproliferative pulmonary hypertension are apoptosis-resistant (11). In a previous study we showed that a dysregulated apoptotic process may be involved in the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix within limb wounds of horses (8). It is thus tempting to speculate that the large endothelial cells we observed in the predominantly occluded microvessels of limb wounds may be apoptosis-resistant, with the opportunity for continued growth (hypertrophy).

The number of pericytes did not differ between patent and occluded microvessels or between body and limb wounds. Furthermore, the wound age and location as well as the status of the microvessel (patent or occluded) did not alter the ratio of endothelial cells to pericytes.

Unambiguous positive identification of pericytes is a challenge. The genetic pericyte marker (promoter trap transgene XlacZ4) is suited for quantification of pericytes since it is in the nucleus, whereas the high-molecular-weight melanoma marker (HMW-MMA; also called NG2 in the mouse) is an excellent surface marker. However, neither represents a panpericyte marker; both are dynamic, their expression varying with species, tissue, or development-related contexts. The most reliable identification is thus currently achieved with electron microscopy (14).

Pericytes, smooth-muscle-like mural cells of capillaries and venules, reside at the interface between the endothelium and the surrounding tissue. They share basement membrane with the endothelial cells and directly contact them through holes in the basement membrane. These heterologous “peg-and-socket” contacts are thought to support transmission of contractile force from the pericytes to the endothelium. Indeed, pericytes possess all the machinery necessary for contraction, are contractile in vitro, and release soluble factors that promote microvessel constriction by up-regulating endothelin-1 and down-regulating nitric oxide synthase production by endothelial cells (18). Furthermore, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) induces α-SMA expression in pericytes, indicating a change to an even more contractile phenotype (19). Earlier studies documented high concentrations of this fibrogenic cytokine in limb wounds of horses (4,20). We thus hypothesized that microvascular occlusion, as documented especially in limb wounds, might result from the presence of a greater number of pericytes in the affected vessel’s wall. Our data do not support this hypothesis, nor do they reflect previous reports of a greater abundance of pericytes in dependent areas of the body (legs) (21). One reason our data may differ from those of Sims and colleagues (21) is that the Sims study did not report the absolute number of pericytes; rather, the length of pericyte luminal membranes was compared with the length of outer endothelial cell membranes. It is thus possible that particularly enveloping pericytes could augment the overall number, even though they may actually be sparse.

Microvascular pericytes can synthesize matrix components and fibroblast-activating cytokines and are thus potential mediators of pathological changes in fibrotic conditions (22). Indeed, Sundberg and associates (23) showed that intramural pericytes migrate into the perivascular space and develop into collagen-synthesizing fibroblasts during excessive dermal scarring, probably under the influence of TGF-β signaling (24).

In view of previous studies showing the influence of TGF-β in the repair of limb wounds in horses (4,10,15,20), we speculated that a greater absolute or relative number of pericytes would be found in limb wounds. Our ratios of endothelial cells to pericytes were similar (P = 0.20), at 3.1849 ± 0.3158 for limb wounds, 2.8104 ± 0.2972 for thoracic wounds, and 3.3244 ± 0.3762 for intact skin. A difference between our study and that of Sundberg and associates (23) that might explain why we did not find more pericytes in limb wounds is that Sundberg’s team counted different subpopulations of pericytes (intramural, juxtaposed to the endothelium; partly dissociated from the microvascular wall; or located in the perivascular space), whereas we counted only pericytes that were intimately associated with the microvascular wall. A search of the literature revealed only 1 other study that published data concerning the ratio of endothelial cells to pericytes: values of 4.35 and 5.55 were associated with systemic and localized scleroderma, respectively (25).

In conclusion, our data suggest that endothelial cell hypertrophy might contribute to the occlusion of microvessels populating the granulation tissue of horse wounds. The role of the pericyte in this anomaly requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Céline Lusignan-Lussier for technical assistance, as well as Guy Beauchamp for statistical analysis and Marco Langlois for help with the figures. The bandage materials were generously donated by Smith-Nephew Canada. Research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, as well as the Fonds Québécois pour la Recherche en Nature et Technologie.

References

- 1.Wilmink JM, van Herten J, van Weeren PR, Barneveld A. Retrospective study of primary intention healing and sequestrum formation in horses compared to ponies under clinical circumstances. Equine Vet J. 2002;34:270–273. doi: 10.2746/042516402776186047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs KA, Leach DH, Fretz PB, Townsend HGG. Comparative aspects of the healing of excisional wounds on the leg and body of horses. Vet Surg. 1984;13:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilmink JM, Stolk PW, van Weeren PR, Barneveld A. Differences in second intention wound healing between horses and ponies: macroscopic aspects. Equine Vet J. 1999;31:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999.tb03791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theoret CL, Barber SM, Moyana TN, Gordon JR. Expression of transforming growth factor β1, β3 and basic fibroblast growth factor in full-thickness skin wounds of equine limbs and thorax. Vet Surg. 2001;30:269–277. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2001.23341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuan TL, Nichter LS. The molecular basis of keloid and hypertrophic scar formation. Mol Med Today. 1998;4:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)80541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kischer CW. The microvessels in hypertrophic scars, keloids and related lesions: a review. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1992;24:281–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kischer CW, Shetlar MR. Microvasculature in hypertrophic scars and the effects of pressure. J Trauma. 1979;19:757–764. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lepault É, Céleste C, Doré M, Martineau D, Theoret CL. Comparative study on microvascular occlusion in body and limb wounds in the horse. Wound Rep Regen. 2005;13:520–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falanga V, Qian SW, Danielpour D, Katz MH, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Hypoxia upregulates the synthesis of TGF-β1 by human dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:634–637. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12483126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz AJ, Wilson DA, Keegan KG, et al. Factors regulating collagen synthesis and degradation during second-intention healing of wounds in the thoracic region and the distal aspect of the forelimb of horses. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63:1564–1570. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakao S, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Lee JD, Wood K, Cool CD, Voelkel NF. Initial apoptosis is followed by increased proliferation of apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2005;19:1178–1180. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3261fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braverman IM, Sibley J. Ultrastructural and three-dimensional analysis of the contractile cells of the cutaneous microvasculature. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95:90–96. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, et al. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:543–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C. Endothelial–pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theoret CL, Barber SM, Moyana TN, Gordon JR. Preliminary observations on expression of transforming growth factor β1, β3 and basic fibroblast growth factor in equine limb wounds healing normally or with proud flesh. Vet Surg. 2002;31:266–277. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2002.32394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber SM. Second intention wound healing in the horse: the effect of bandages and topical corticosteroids [abstract] Proc Am Assoc Equine Pract. 1989;35:107. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theoret CL, Barber SM, Moyana TN, Townsend HGG, Archer J. Repair and function of synovium after arthroscopic synovectomy of the dorsal compartment of the equine antebrachiocarpal joint. Vet Surg. 1996;25:142–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1996.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin AR, Bailie JR, Robson T, et al. Retinal pericytes control expression of nitric oxide synthase and endothelin-1 in microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2000;59:131–139. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbeek MM, Otteholler I, Wesseling P, Rutter DJ, Dewaal RMW. Induction of alpha smooth muscle actin expression in cultured brain pericytes by transforming growth factor beta 1. Am J Pathol. 1994;44:372–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van den boom R, Wilmink JM, O’Kane S, Wood J, Ferguson MWJ. Transforming growth factor-β levels during second-intention healing are related to the different course of wound contraction in horses and ponies. Wound Rep Regen. 2002;10:188–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims D, Horne MM, Creighan M, Donald A. Heterogeneity of pericyte populations in equine skeletal muscle and dermal microvessels: a quantitative study. Anat Histol Embryol. 1994;23:232–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1994.tb00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajkumar VS, Sundberg C, Abraham DJ, Rubin K, Black CM. Activation of microvascular pericytes in autoimmune Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:930–941. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<930::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundberg C, Ivarsson M, Gerdin B, Rubin K. Pericytes as collagen-producing cells in excessive dermal scarring. Lab Invest. 1996;74:452–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonelli-Orlidge A, Saundeers KB, Smith SR, D’Amore PA. An activated form of transforming growth factor beta is produced by cocultures of endothelial cells and pericytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4544–4548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmbold P, Fiedler E, Fischer M, Marsch WC. Hyperplasia of dermal microvascular pericytes in scleroderma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2004.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]