Abstract

We present crystal structures of the calcium-free E2 state of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, stabilized by the inhibitor thapsigargin and the ATP analog AMPPCP. The structures allow us to describe the ATP binding site in a modulatory mode uncoupled from the Asp351 phosphorylation site. The Glu439 side chain interacts with AMPPCP via an Mg2+ ion in accordance with previous Fe2+-cleavage studies implicating this residue in the ATPase cycle and in magnesium binding. Functional data on Ca2+ mediated activation indicate that the crystallized state represents an initial stage of ATP modulated deprotonation of E2, preceding the binding of Ca2+ ions in the membrane from the cytoplasmic side. We propose a mechanism of Ca2+ activation of phosphorylation leading directly from the compact E2-ATP form to the Ca2E1-ATP state. In addition, a role of Glu439 in ATP modulation of other steps of the functional cycle is suggested.

Keywords: Ca2+-ATPase, membrane protein crystallography, modulatory, P-type ATPase, transport

Introduction

The sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is a member of the P-type ATPase cation pump family. These pumps maintain the electrochemical gradients for cations across biomembranes (Moller et al, 1996) and play a key role in cell biology. Ca2+-ATPases maintain calcium gradients and potentiate the Ca2+-mediated signaling networks (Carafoli, 2002). The lumen of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum serves as a calcium store in most cells and calcium pumps positioned in these membranes maintain a steep Ca2+ gradient as required for fast calcium-mediated signaling. The control of actin–myosin activity in muscle tissue represents a prominent and well-studied example of Ca2+-mediated signaling (Hasselbach and Makinose, 1961). SERCA is thus responsible for the reuptake of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in muscle, where it ensures the efficient relaxation at the end of a contraction event. Ca2+-ATPases have recently attracted attention as a putative drug target against slowly proliferating cancer cell lines such as prostate cancer (Denmeade et al, 2003; Sohoel et al, 2006) and also recently as the probable target of antimalarials belonging to the artemisinin family (Eckstein-Ludwig et al, 2003; Uhlemann et al, 2005).

The functional cycle of P-type ATPases is typically denoted by E1 and E2 states that for SERCA relate to the binding and active transport of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and the countertransport of luminal H+ to the cytoplasm, respectively. In Ca2+ translocation, ATP is involved as the key substrate in the formation of the Ca2+ occluded E1∼P state. The details of this reaction have been thoroughly worked out in biochemical and structural studies (Pickart and Jencks, 1982; Andersen and Vilsen, 1992; Sorensen et al, 2004). However, ATP at physiological concentrations also exhibits a general, stimulatory effect on the functional cycle of SERCA relating to a noncatalytic, modulatory mode of binding to the various ATPase intermediates as depicted in Figure 1. Thus, an acceleration is observed of (i) the E2 to Ca2E1 transition associated with Ca2+ binding after dephosphorylation (Guillain et al, 1981; Fernandez-Belda et al, 1984; Stahl and Jencks, 1984; Mintz et al, 1995); (ii) the E2P to E2 transition associated with dephosphorylation (McIntosh and Boyer, 1983; Champeil et al, 1988); and (iii) the Ca2E1∼P to E2P transition promoting Ca2+ translocation (Champeil and Guillain, 1986; Wakabayashi et al, 1986; Lund and Moller, 1988). For Na+,K+-ATPase, it is specifically the K2E2 to Na3E1 transition of the Na+,K+-ATPase that is accelerated by ATP (Post et al, 1972; Glynn, 1984; Forbush, 1987). Thus, besides being a catalytic substrate, ATP is a stimulatory cofactor, and this function is likely to be of general importance in the P-type ATPase family. A key question as to the mechanism of SERCA is then to address the structural and functional properties of the modulatory ATP binding site in comparison to the catalytic site and to make possible extrapolations to other P-type ATPases.

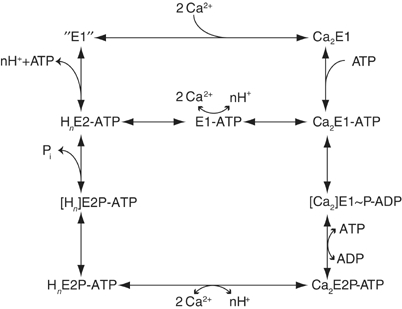

Figure 1.

Functional cycle of the Ca2+-ATPase from the SERCA, with an indication of the steps that probably are subject to modulation by noncovalently bound ATP. The upper part of the branched pathway for processing of the HnE2-ATP intermediate shows the classical scheme (binding of Ca2+ followed by binding of ATP), whereas the lower branch, retaining the previously bound ATP, shows a more direct pathway to the Ca2E1-ATP intermediate, that precedes phosphorylation of the ATPase.

There is strong evidence from mutational studies (Clausen et al, 2003; McIntosh et al, 2003) and X-ray crystallography (Sorensen et al, 2004; Toyoshima and Mizutani, 2004) for a direct involvement of the conserved residues in the N-domain in nucleotide binding of rabbit SERCA1a . In this connection, it is of interest that Glu439 also has a prominent effect on the ATPase rate of SERCA (Inesi et al, 2004) and is of great importance for a proper structural response of bound nucleotide to proteolytic cleavage (Ma et al, 2003). Attention to this residue has also come from Fe2+-induced hydroxyl-radical cleavage studies, which suggest that Glu439 in SERCA (Hua et al, 2002; Montigny et al, 2004), the equivalent Asp443 in pig renal Na+,K+-ATPase (Patchornik et al, 2002; Strugatsky et al, 2003, 2005) and Asp459 in gastric H+,K+-ATPase (Shin et al, 2001), are in direct contact with the nucleotide binding site via a divalent cation during the functional cycle. However, when we look at this residue in the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− and Ca2E1-AMPPCP structures (Sorensen et al, 2004), we see that Glu439 is in a rather exposed position and not in direct contact with any of the ligands, including Mg2+.

Another puzzling observation relates to the structure of SERCA in the Ca2E1 state, which exhibits an open conformation with the N- and A-domains detached from the P-domain (Toyoshima et al, 2000). The functional relevance of this nucleotide-free form can be disputed, considering that the physiological concentrations of ATP in muscle tissue are maintained at a millimolar level, sufficient to effectively saturate ATP binding to all ATPase intermediates (Figure 1).

To address the modulatory effect of ATP and the mechanism of Ca2+-mediated activation of phosphorylation, we have determined crystal structures at 3.1 and 2.8 Å resolution of SERCA representing an E2-ATP state. This was achieved by use of the stabilizing inhibitor thapsigargin (Tg) and the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPCP. An isomorphous crystal form obtained in the absence of nucleotide was solved at 3.1 Å resolution, and isomorphous crystals without thapsigargin were analyzed at low resolution. Along with the structural data, we have conducted biochemical experiments to further understand the effect of thapsigargin.

Results

E2(Tg)-AMPPCP, E2-AMPPCP, and E2(Tg) form

Crystals of calcium-free E2(Tg)-AMPPCP, E2-AMPPCP, and E2(Tg) complexes were obtained by vapor diffusion using protein prepared in the presence of native lipids from sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes. Crystallographic data were collected using synchrotron radiation (Table I). The structure of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex representing an E2-ATP state was solved at 2.8 and 3.1 Å resolution from two similar crystals forms showing P41212 symmetry with one molecule per asymmetric unit (Figure 2A). Crystals of the thapsigargin-free E2-AMPPCP form appear isomorphous to E2(Tg)-AMPPCP with respect to growth conditions, morphology and unit cell dimensions. However, it was not possible to collect a data set, possibly due to radiation sensitivity. The unit cell dimensions of E2(Tg)-AMPPCP and E2-AMPPCP are similar to published structures of the nucleotide-free E2(Tg) (Toyoshima and Nomura, 2002) and E2(Tg, dibutyldihydroxybenzene (BHQ)) forms (Obara et al, 2005) structures which were, however, solved in the lower space group P41 with two molecules per asymmetric unit (PDB entries 1IWO and 2AGV). Unfortunately, we have been unable to compare these latter forms to ours on the basis of experimental data since the structure factor amplitudes are not available. We therefore crystallized the E2(Tg) form (also in our hands exhibiting P41212 symmetry) and collected data sets extending to 3.1 and 3.3 Å resolution, allowing us to calculate isomorphous difference Fourier maps between nucleotide-bound and nucleotide-free crystal forms (Figure 2B) and to refine a nucleotide-free structure (Table I). The difference map clearly identifies the ATP analog by the presence of electron density extending to a 7σ level at the nucleotide binding site of the N-domain and protruding towards the interface to the P-domain (Figure 2B). The same map also shows local conformational changes centered on the Glu439 residue, which is engaged in nucleotide binding via a magnesium ion bound between the α- and β-phosphate groups of the ATP analog (see below). The two forms of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP-complex were obtained at similar buffer conditions (pH 6.8 and 1 mM AMPPCP), but displayed rather different occupancies at the nucleotide binding site (assigned as 100 versus 25% in refinement, Table I). A variability also noted in similar studies of a complex with a thapsigargin-based derivative (Sohoel et al, 2006).

Table 1.

Data and refinement statistics

| E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form 1 | E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form 2 | E2-AMPPCP | E2(Tg) form 1a | E2(Tg) form 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 (P4) | P41212 | P41212 |

| Cell dimension (Å) | a=b=71.5 | a=b=71.3 | a=b=71.5 | a=b=71.7 | a=b=71.5 |

| c=590.2 | c=588.0 | c=590 | c=588.3 | c=589.4 | |

| Beam line/station | EMBL/DESY X11 | BESSY BL14.2 | BESSY BL14.2 | BESSY BL14.2 | ESRF BM14.1 |

| Wavelenght (Å) | 0.8116 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.9184 | 0.8551 |

| Resolution (Å)b | 90–3.1 (3.17–3.1) | 30–2.8 (3.01–2.8) | 30–6 | 30–3.3 (3.38–3.3) | 80–3.1 (3.17–3.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (99.8) | 92.5 (75.6) | No data set collected | 99.5 (99.9) | 99. 6 (100.0) |

| Unique reflections | 29134 | 36066 | 24661 | 29045 | |

| Redundancy | 7.8 (7.8) | 5.7 (3.6) | 6.6 (6.4) | 6.7 (6.9) | |

| Rsym (%)c | 11.7 (59.5) | 7.4 (37.2) | 16.8 (73.7) | 10.3 (72.7) | |

| I/óI | 19.6 (3.7) | 17.1 (3.6) | 16.9 (3.6) | 20.8 (2.8) | |

| Wilson B-factor | 77.9 | 62.8 | 84.8 | 84.5 | |

| Refinement | No model refined | ||||

| Residues and ligands | 994 | 994 | 994 | ||

| AMPPCP, 1 Mg2+, 1 Na+, Thapsigargin | (AMPPCP, 1 Mg2+), 1 Na+, Thapsigargin | 1 Na+, Thapsigargin | |||

| Nucleotide occ.d | 1.0 | 0.25 | — | ||

| Resolution (Å)b | 15–3.1 (3.3–3.1) | 15–2.8 (3.0–2.8) | 15–3.1 (3.3–3.1) | ||

| R/Rfree (%)e | 26.1/31.0 | 25.2/30.8 | 24.9/30.6 | ||

| (37.2/41.5) | (34.5/38.4) | (37.2/46.6) | |||

| Ramachandran (%)f | 80.3/18.6/0.7/0.3 | 83.6/16.1/0.2/0.0 | 81.1/17.6/1.1/0.1 | ||

| R.m.s.d. bonds (Å) | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||

| R.m.s.d. angles (deg) | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ||

| Average B-value (Å2)d | 63.1 | 67.2 | 71.5 | ||

| PDB code | 2C88 | 2C8K | 2C8L | ||

| Data set collected for optimal isomorphous difference Fourier map against E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form 1 (see Figure 2B). | |||||

| Values in parentheses here and below refer to the high-resolution shell as indicated. | |||||

| Rsym=∑h∑i∣Ii(h)−〈I(h)〉∣/∑h∑i∣Ii(h), Ii(h) is the ith measurement. | |||||

| Occupancies were estimated on the basis of Fobs−Fcalc difference Fourier maps and B-factor comparisons between ligand and binding pocket of the protein. | |||||

| R=∑h∣∣F(h)obs∣−∣F(h)calc∣∣/∑h∣F(h)obs∣. Rfree is the R-factor calculated for a randomly picked subset of approx. 1000 reflections excluded through-out the refinement. The same test set was used for all P41212 forms. | |||||

| Fractions of residues in ‘most favorable', ‘allowed', ‘generously allowed' and ‘disallowed' regions of the Ramachandran plot according to PROCHECK (Laskowski et al, 1993). | |||||

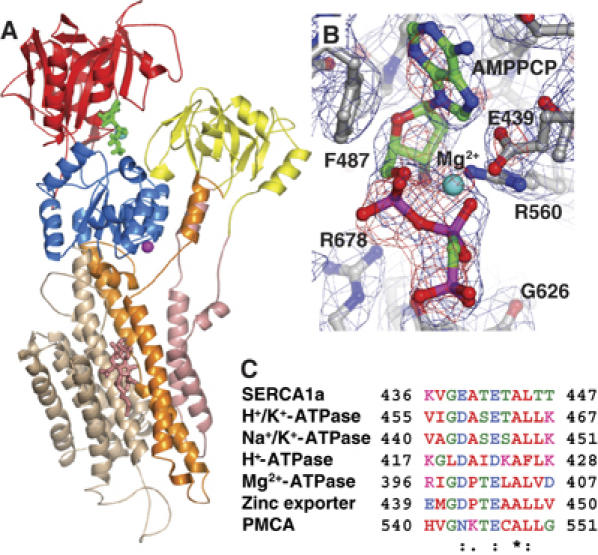

Figure 2.

Structure of the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex. (A) The overall structure of the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP form shown in cartoon with individual domains colored as follows: A-domain (residues 1–43 and 123–230) in yellow, the M1–M2 membrane segments (residues 44–122) in pink, the M3–M4 membrane segments (residues 231–345) in orange, the P-domain (residues 346–360 and 606–739) in blue, the N-domain (residues 361–605) in red, and the C-terminal M5–M10 domain (residues 740–994) in wheat. The AMPPCP nucleotide at the N domain is shown in green sticks, the inhibitor Tg in the transmembrane region is shown in pink sticks and a sodium ion is shown as a magenta sphere. (B) An Fobs[HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP]−Fobs[HnE2(Tg)] difference Fourier map calculated at 3.3 Å resolution is displayed in red mesh at 2.5σ level showing unbiased electron density corresponding to the MgAMPPCP nucleotide complex as well as a fixed conformation of the Glu439 side chain contacting the magnesium ion. The final model-based electron density map was calculated at 3.1 Å resolution and displayed at the 1σ level in blue mesh showing again the structure of AMPPCP bound to the HnE2(Tg) form of SERCA. The refined model is indicated in ball-and-stick representation. (C) Alignment of a wide range of P-type ATPases identifying Glu439 as a semiconserved residue, found as either Asp or Glu, except in SPCA (secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase) where it is Lys.

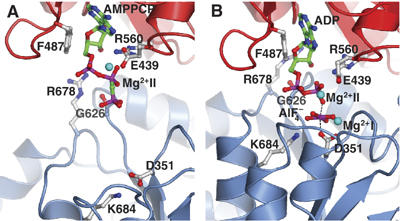

The nucleotide in E2(Tg)-AMPPCP adopts a slightly different conformation compared to the structures of the Ca2E1-AMPPCP and Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− forms. Contacts at the P-domain are different from the nucleotide-bound E1 forms (Table II). The γ-phosphate group is positioned 9 Å away from the Asp351 phosphorylation site. The canonical Mg2+ binding site of the haloacid dehalogenase superfamily (Aravind et al, 1998) in nucleotide-bound E1 forms coordinated by Asp351, Thr353, Asp703, and the γ-phosphate group (Sorensen et al, 2004; Toyoshima and Mizutani, 2004) is not occupied. In the N-domain, the ATP binding site is primarily formed by residues that are also involved in nucleotide binding in the E1 forms (Sorensen et al, 2004), but the nucleotide bound in modulatory mode is more exposed and not tightly fitted into its binding site compared to the catalytic mode (Table II). The base plane is twisted by approximately 30° with respect to the binding pocket with the consequence that, for example, coplanar stacking to the Phe487 side chain (as observed in nucleotide-bound E1 forms) is perturbed in the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form (Figure 3). We also find that in the E2 state the α,β-phosphate groups of ATP interact with Glu439 of the N-domain via a Mg2+ ion. The Fobs[E2(Tg)-AMPPCP]−Fobs[E2(Tg)] difference Fourier map reveals that the Glu439 side chain has become fixed in a fully extended conformation (Figures 2B and 3A) to achieve this interaction. It appears to form hydrogen bonds to water molecules which together with the α- and β-phosphate groups of AMPPCP are part of the octahedral coordination sphere of the Mg2+ ion. This Mg2+ site we denote as site II to differentiate it from the canonical Mg2+ binding site (denoted site I) involved in phosphorylation of the ATPase. The Arg560 residue of the N-domain also interacts with the α- and β-phosphate while the Arg678 residue approaches the ribose moiety, albeit too far away for hydrogen bonding. Interestingly, both the Mg2+ ion of site II and Arg560 are in direct contact with the oxygen bridging the α- and β-phosphate groups, in agreement with previous observations on the requirement of this bridging oxygen atom for a nucleotide-assisted protection against proteolytic degradation (Ma et al, 2003). The γ-phosphate group forms a loose contact to the periphery of the P-domain at the Gly626 region (at the TGD motif, Figures 2 and 3). These interactions must occur via a solvation layer, which then will allow for a smooth transition to the catalytic mode where the intimate contact between the γ-phosphate and the phosphorylation site becomes stabilized by the Mg2+ site I (see further below).

Table 2.

Nucleotide contacts in various functional states of SERCA

| Nucleotide surface | E2(Tg)-ADP-MgF42− (E2-Pi-ADP) | E2(Tg)-AMPPCP (E2-ATP) | Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− (Ca2E1∼P-ADP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buried surface area (Å2)a | 808 | 852 | 901 |

| Solvent-accessible area (Å2)a | 187 | 172 | 35 |

| Contacts to nucleotide | Modulatory | Modulatory | Catalytic |

| A-domain | |||

| Ile188 | + | ||

| Lys205 | + | ||

| P-domain | |||

| Asp351 | + | ||

| MgI2+b | + | ||

| Lys352 | + | ||

| Thr353 | + | ||

| Thr625 | + | ||

| Gly626 | + | + | + |

| Asp627 | + | ||

| Arg678 | + | + | |

| Lys684 | + | ||

| Asp703 | + | ||

| Asn706 | + | ||

| N-domain | |||

| Glu439 | + | ||

| Thr441 | + | ||

| Glu442 | + | + | + |

| Phe487 | + | + | + |

| Arg489 | + | ||

| Met494 | + | + | + |

| Lys515 | + | + | + |

| Gly516 | + | + | + |

| Ala517 | + | + | |

| Arg560 | + | + | + |

| Cys561 | + | ||

| Leu562 | + | + | + |

| Buried surface and solvent-accessible surface areas refer to MgADP in E2(Tg)-MgF42−-ADP (Toyoshima et al, 2004), to MgAMPPCP in E2(Tg)-AMPPCP, and to MgADP:AlF4− in Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− (Sorensen et al, 2004). The magnesium ions correspond to site II between α- and β-phosphate groups (see Figure 3). The values listed for the E2(Tg)-MgF42−-ADP complex would have to be increased considering a true ATP modulatory substrate with an additional γ-phosphate group (estimated 25 Å2). | |||

| Mg2+I corresponds to the catalytic Mg2+ site I associated with Asp351, Thr353, Asp703 and γ-phosphate (the latter mimicked by AlF4−). | |||

Figure 3.

Comparison of the modulatory and the catalytic ATP binding site in SERCA. (A) The modulatory ATP binding site in the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure; compared with (B) the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− structure. The N and P domain are shown in red and blue cartoon with important residues, involved in ATP binding, shown in ball-and-stick representation. The A domain is excluded for clarity. The ATP-like ligands, AMPPCP or ADP:AlF4− are shown in ball-and-stick and the Mg2+ ions at sites I and II as cyan spheres. The phosphorylation site is inactive in (A) corresponding to the Ca2+-free state, whereas it is occluded in (B) corresponding to the occluded Ca2+-bound state.

Except for the presence of nucleotide and local conformational changes, the overall structure of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form is similar to that of the E2(Tg) complex (Figure 2A). This includes the structure of the transmembrane region, which is nearly identical to that of the proton occluded E2(Tg):AlF4− complex (Olesen et al, 2004). We therefore interpret the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure as representing a protonated HnE2-ATP state.

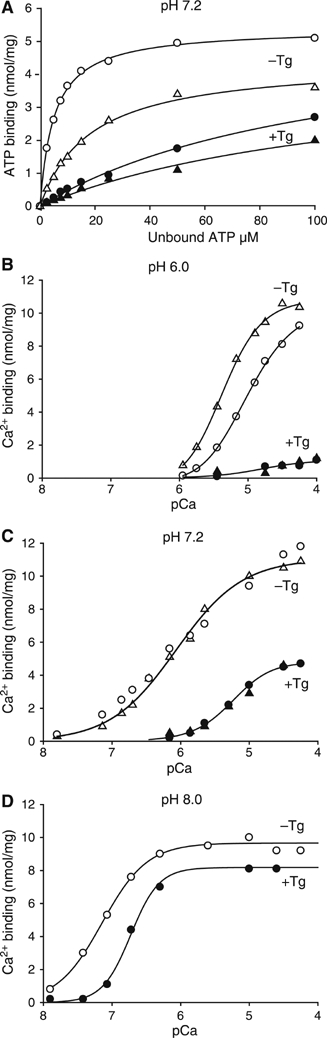

Concerning the functional properties of the thapsigargin-stabilized E2 form of membranous Ca2+-ATPase, we have found that ATP binding is retained, although with a reduced affinity compared to that of the thapsigargin-free E2 form (Figure 4A). The Kd of ATP binding is 150 μM for E2(Tg) versus 30 μM for E2 (at pH 7.2 and absence of divalent cation by addition of EDTA), and there is a moderate stimulatory effect of Mg2+ on the ATP binding process with a Kd of 100 μM for E2(Tg), to be compared with 5 μM for E2 (at pH 7.2 and a free concentration of about 1 mM Mg2+). The Ca2+ binding properties of the two forms are compared in Figures 4B–D. While at pH 6.0 there is little binding of Ca2+ by E2(Tg) (Figure 4B), one binding site with a reduced Ca2+ binding affinity can be detected at pH 7.2 (Figure 4C), and two binding sites are present at pH 8.0 with only a modest decrease in affinity (Figure 4D). Ca2+ binding by the E2 state of SERCA (in the absence of thapsigargin) is not affected at pH 7.2 by the presence of 1 mM AMPPCP (Figure 4C), whereas at pH 6.0 (Figure 4B) Ca2+ binds with a higher affinity and with more distinct cooperativity (the Hill coefficient at pH 6.0 is increased from 1.3 to 1.7 by addition of 1 mM AMPPCP). These latter results are in agreement with the well-known nucleotide acceleration of the Ca2+/H+ exchange mechanism of the fully protonated E2 form, HnE2 (Mintz et al, 1995). AMPPCP does not affect Ca2+ binding in the presence of thapsigargin (Figure 4B and C). We conclude that our data are consistent with thapsigargin stabilizing the ATPase in the protonated HnE2 state at pH 6.0, and that E2(Tg) gradually recovers the ability to bind Ca2+ with increasing pH (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of Tg on ATP, MgATP and Ca2+ binding. (A) ATP and MgATP-binding to Ca2+-ATPase in the E2 state in the presence of 1 mM EDTA (Δ,▴), or in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ and 1 mM EGTA (○, •), in media containing 100 mM Mops/Tris (pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, and various concentrations (2.5–100 μM) of [C14]ATP. (B–D) Ca2+ binding measurements performed on Tg reacted (•, ▴) and untreated (o, Δ) ATPase with media buffered at pH 6.0, 7.2, or 8.0, respectively, together with 100 mM KCl, 1 mM Mg2+, in the absence (○, •) or presence (Δ, ▴) of 0.5 mM AMPPCP, and in the presence 0.05 or 0.10 mM Ca2+ and various concentrations of EGTA (at pH 6.0 and 7.2), or BAPTA (at pH 8.0) to adjust the free concentration of Ca2+. For the calculation of pCa, the dissociation constants given by Mintz et al (1995) were used.

Discussion

Overall structure of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP form

We find the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure to represent an initial state of the E2 to E1 transition. At pH 8 the E2 form readily releases counter-transported protons and has similar Ca2+ binding properties in the absence and presence of thapsigargin. In contrast, we observe a clear inhibition by thapsigargin at pH 6 (Figure 4B), which shows that thapsigargin stabilizes the fully protonated HnE2 state. This is further supported by crystallographic studies of the proton-occluded HnE2:AlF4− form that we have obtained in the presence and absence of thapsigargin (Olesen et al, 2004; Olesen et al, in preparation), and whose structures, as far as the transmembrane region is concerned, are virtually identical to that of E2(Tg)-AMPPCP. While the overall arrangement of the cytoplasmic domains of the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP form bears some resemblance to HnE2:AlF4− (mimicking the E2P transition state of dephosphorylation), a key difference is the loosening of intimate interactions of the A-domain and its linkers with the P-domain and the membrane. This causes the retraction of the TGES motif of the A-domain away from the phosphorylation site allowing the N-domain with bound nucleotide to move closer to the P-domain (Figure 5). The result is an arrangement of the cytoplasmic domains, which is inbetween that of the E2P transition state and the Ca2E1∼P-ADP state, yet still with an inclination of the entire, cytoplasmic head-piece towards the membrane. These observations are consistent with the view that after nucleotide binding and E2P dephosphorylation, a gradual transition takes place from the E2-ATP state, where ATP is bound in the modulatory mode, to the Ca2E1-ATP state where ATP is bound in the catalytic mode. There is therefore only one ATP binding site in SERCA, but it switches between modulatory and catalytic modes.

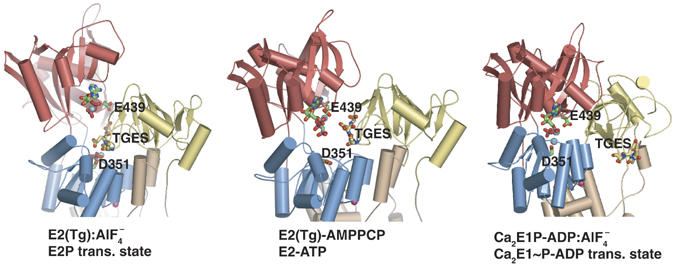

Figure 5.

Conformational changes of the cytoplasmic domains, showing how the ATP-bound E2 intermediate represents a form between the E2P transition state of dephosphorylation (left-hand figure) to the transition form of the phosphorylated state, represented by Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− (right-hand figure). The structures have been aligned on the basis of superpositioning of the molecules on the C-terminal M7–M10 segments. The TGES motif in the A domain is highlighted with sphere representation. Color codes as in Figure 2A. The position of ADP was adopted from the 1WPG structure (Toyoshima et al, 2004) and docked into the E2P transition state represented by 1XP5 (Olesen et al, 2004) on the basis of an alignment of the N-domain. Note the gradual closure of the N- and P-domains and the gradual transition from an exposed nucleotide binding site in the modulatory mode to an almost completely buried site in the catalytic mode.

Deprotonation of the HnE2 state modulated by ATP binding

The H+/Ca2+ exchange rate on the cytoplasmic side is accelerated considerably by ATP binding to E2, particularly for the fully protonated HnE2 form (Mintz et al, 1995). Furthermore, the absence of thapsigargin results in an increased Ca2+ affinity below pH 7 (Figure 4B). Thapsigargin, on the other hand, decreases the ATP affinity of the E2 state. This is well explained by thapsigargin stabilizing the protonated E2 form, and thus blocking the stimulatory effect of ATP on cation exchange. Based on these observations, we conclude that our structure of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex represents a genuine HnE2-ATP state, trapped at an initial stage of transition to E1 states. This is further supported by our analysis of crystals of the E2-AMPPCP complex obtained at pH 6.2 without thapsigargin (Table I).

How can we envision that ATP binding stimulates Ca2+ binding and accelerates the HnE2 to Ca2E1 transition? The stimulation of H+/Ca2+ exchange by ATP binding must be described in terms of a cooperative mechanism, which is mediated both by the cation binding helices traversing the membrane and the cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domains. We are not in a position to observe the full expression of this cooperativity in the crystal structures because of the inhibitory effect of thapsigargin on both Ca2+ and ATP binding. However, what we can see from the structure is that proceeding from the E2P transition state to the dephosphorylated E2 state those parts of the peptide chain that connect the A-domain with the membrane (the A-M1, M2-A, and A-M3 linker regions) loosen their grip on the surface of the P-domain, thereby removing the TGES motif from its intimate contact with the phosphorylation site and destabilizing the proton-occluded state (cf also Figure 2B in Olesen et al, 2004). We propose that the tighter association of the P-domain with the N-domain mediated by modulatory ATP in the E2 state leads to exposure of the buried M3–M4 and M5–M6 segments on the cytoplasmic site. It should be noted that during the nucleotide binding transition the N-terminal end of M5 (Asp738–Val744) gets in intimate contact with residues Thr355–Leu356 and Arg604–Cys614 that form part of the hinge between the N- and P-domains. This interaction may also play an important role in the ‘cross-talk' between the membranous and the cytoplasmic regions, and between Ca2+ and ATP binding. The changes are probably accompanied by an increase in the cytoplasmic accessibility of the cation binding region, whose structure also becomes adapted for Ca2+ binding by rearrangement of liganding functionalities from a proton-occluded state. The conformational changes at the nucleotide binding site effecting a closer approach of the P-domain to the N-domain will be easily met, considering the high level of solvation of the interface of the nucleotide and the P-domain as observed in the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure (Figures 2 and 3, Table II).

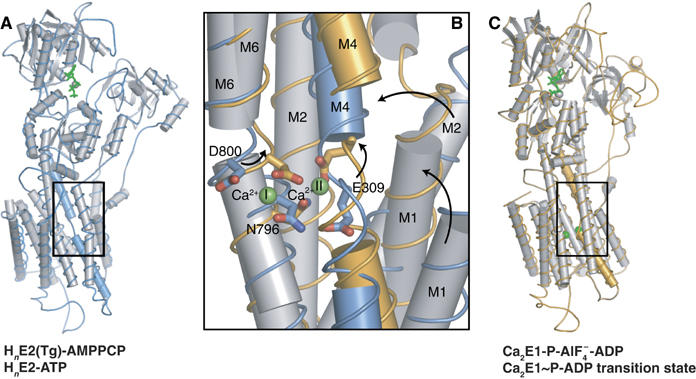

Activation of the phosphorylation site by Ca2+ binding

As mentioned above, only small conformational changes are observed in the membrane by comparison of the E2(Tg) and E2(Tg)-AMPPCP forms. This may include the position of the Glu309 residue, which has been pinpointed as a gating residue in Ca2+ binding (Inesi et al, 2004). The Glu309 residue in our structures adopts an inward facing conformation burying the carboxy-group, as has also been reported in the E2(Tg, BHQ) structure (Obara et al, 2005), yet unlike the previously reported structure of the E2(Tg) form where the carboxy-group was placed in a solvent-exposed position (Toyoshima and Nomura, 2002). Regardless of the putative role of Glu309 in Ca2+ gating, this residue undoubtedly plays a central role for phosphoryl transfer from ATP to Asp351, which only occurs upon binding of the second Ca2+ ion in the membrane. While Ca2+-binding at the first site in the membrane requires just minor adjustments of residues in M5 and M6, the binding of the second Ca2+ ion at the 304VAAIPE309 motif forming a Ca2+-binding kink in M4 involves large conformational changes that are revealed by comparison of the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP with the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− structure (Figure 6). Focusing on the latter form these changes comprise an upward, translational shift and a ∼20° inclination of the M4 segment, imposing similar movements of M3. The C-terminal end makes a turn at Asn330 from where it runs below the P-domain and proceeds into the central N-terminal segment of the P-domain containing the Asp351 phosphorylation site (Figure 3). As a result, the translational movement of M4 towards the cytoplasmic side exerts a push on the P-domain, which rotates towards the N-domain (Figure 5). In the case of the N-terminal end of the M3 helix, attached to the A-domain, the M4-associated translational shift and 20° turn of the direction upon Ca2+ binding to the E2 state pulls out the A-domain with the TGES motif positioned as a plug between the N- and the P-domain (Figures 5 and 6). The N- and P-domains, held together by ATP, can now come together to form the catalytic site of the Ca2E1-ATP, with the γ-phosphate and the side chain of Asp351 positioned for phosphoryl transfer by Mg2+ site I. As mentioned before the contacts of ATP to the P-domain in the E2 state are weak and solvated. This allows for the facile transition of the modulatory site to the entirely closed state of the Ca2E1-ATP form, triggered by calcium binding at site II. As a result, the interactions of ATP with the ATPase become tight and specific, ultimately resulting in phosphorylation of the Asp351 residue.

Figure 6.

Conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding to nucleotide bound ATPase. (A) Overall representation of HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure shown in gray cartoon with cylindrical helices, and with the M4 helix colored blue. (B) Close-up view of the Ca2+ binding site with HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP form (blue) superpositioned (on residues 800–994) on the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− form (orange). (C) Overall representation of Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− corresponding to (A), but with the M4 helix shown in orange. In all figures, the nucleotide is shown in green ball-and-stick representation, Ca2+ ions are shown as green spheres and key residues involved in Ca2+ binding in ball-and-stick representation with blue (E2) and orange (E1).

ATP modulation of dephosphorylation

Going now back in the functional cycle, the modulatory mode of the ATP binding site revealed by the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure prompts us to address the stimulatory role of ATP on dephosphorylation (the E2P to E2 transition). Elements of the modulatory ATP site relating to the E2P transition state can be deduced from the reported HnE2(Tg)-MgF42− complex containing bound ADP (Toyoshima et al, 2004). The nucleotide binding site of this form is in a far more exposed position than in the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex (Table II). It involves residues in the A-domain (Ile188, Lys205) rather than the Glu439 side chain. Interestingly, the comparison of the HnE2(Tg):AlF4− structure (or the related HnE2(Tg)-MgF42− form) with the HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP form (representing the HnE2P transition state and HnE2-ATP state, respectively) reveals the formation of a putative release tunnel for the liberated inorganic phosphate (represented by MgF42− in Figure 7), appearing upon dislocation of the conserved TGES motif from the phosphorylation site. It is indeed likely that in this position nucleotide binding to the E2P enzyme will promote release of the liberated phosphate upon dephosphorylation, due to electrostatic repulsion from the triphosphate group, especially if charge compensation by Mg2+ ion is absent. This is in agreement with kinetic experiments on E2P dephosphorylation (Champeil et al, 1988). An additional effect causing ATP modulation of dephosphorylation may stem from a destabilization of the interface between the N- and A-domains in the E2P transition state, where we observe Glu439 to form a hydrogen bond to Ser186 in the nucleotide-free E2(Tg):AlF4− structure. This interaction will be affected by ATP, since Glu439 (via Mg2+) becomes engaged in ATP binding in the E2 product state of dephosphorylation (Figure 7B). The destabilization of the A-domain interface upon release of the liberated phosphate provides extra mobility of the A-domain and the M1 through M3 linkers, as required for the departure from the proton-occluded state (Olesen et al, 2004). Interestingly, a Ser186Phe mutation in the SERCA2b isoform is associated with the hereditary Darier skin disease, and this mutant form was indeed shown to display a very slow dephosphorylation rate (Dode et al, 2003).

Figure 7.

ATP modulation of dephosphorylation. (A) Surface and cartoon representation showing the interaction between Glu439 and Ser186 and the buried phosphate group in the E2P product state as represented by MgF42− in the E2(Tg)-MgF42− structure (from PDB entry 1WPG (Toyoshima et al, 2004)). The A and P domain are shown in yellow and blue surface representation and the N domain in red cartoon. The nucleotide and key amino acids are shown in green and gray sticks, respectively. (B) The HnE2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure showing the relaxed interaction of the A- and N domain as a result of the binding of modulatory MgATP by Glu439. The putative phosphate release tunnel that is seen in (A) is exposed due to displacement of the TGES motif from the phosphorylation site. The phosphate group has been modeled into the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP structure as represented by the MgF42− group of E2(Tg)-MgF42− on the basis of a structural alignment of the P-domain. (C) The suggested mechanism of Glu439 assisted phosphoryl transfer initiating the Ca2E1∼P to E2P transition. A hypothetical contact of Glu439 to the MgADP leaving group (shown in sticks) facilitates the phosphorylation of Asp351 (modeled), destabilizing the interface between the N- and P-domains and leading to the transition to the E2P state. The N domain is colored in red and the P domain in blue cartoon, while the A domain has been omitted for clarity.

ATP modulation of the Ca2E1∼P to E2P transition

The Mg2+ site II observed in the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex is equivalent to the second Mg2+ ion observed in the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− complex, which has previously been proposed to stabilize the ADP leaving group after phosphorylation of Asp351 (Sorensen et al, 2004). We therefore suggest that Glu439 may play an important role in catalysis by stimulating the separation of ADP from the phosphorylation site in the Ca2E1∼P-ADP state (Figure 7C). Using the Glu439-MgAMPPCP arrangement observed in the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP complex, we reach at a hypothetical model of the product-separated Ca2E1∼P-ADP state where Glu439 via the second Mg2+ ion attracts the ADP leaving group, permitting the formation of Ca2E1∼P and its further transition to the E2P state. A similar mechanism was previously proposed, based on H2O2 induced Fe2+-cleavage data for Ca2+-ATPase (Montigny et al, 2004). The importance of Glu439 for catalysis is further indicated by the impaired response to proteolytic cleavage (Ma et al, 2003) and decreased ATPase activity of the Glu439Ala mutant of SERCA (Inesi et al, 2004). Glu439 therefore appears to be important for the ATP modulated acceleration of the E1P → E2P transition that has been observed in kinetic experiments (Champeil and Guillain, 1986; Wakabayashi et al, 1986; Lund and Moller, 1988). While all P1 and P2 type ATPases are subject to ATP modulation of the E2 → E1 transition in the 100 μM to millimolar range, modulation of the E1P → E2P transition has only been observed in SERCA. In this connection, we wish to point out that the presence of a glutamate residue at position 439 in the 437VGEATE motif is unique for SERCA of all animal species; it is in general replaced by an aspartate in other P-type ATPases, by asparagine in plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase, and by lysine in the secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase (cf Figure 2C). We propose that the longer hydrocarbon chain of Glu439 in SERCA may be important to establish the formation of a sufficiently flexible arm for the product separation of MgADP from the ATPase in the Ca2E1∼P-ADP configuration.

The functional cycle of Ca2+-ATPase

A model of the functional cycle of SERCA emerges where a compact arrangement of the cytoplasmic domains is maintained throughout all intermediary steps of the functional cycle (Figures 1, 5 and 6). This notion questions the physiological relevance of the open Ca2E1 conformation as an intermediate in the transport scheme, since under physiological conditions with a large ATP to ADP ratio, the modulatory site will be saturated by ATP, allowing the compact E2 state to circumvene the open Ca2E1 conformation and to slip directly into the compact Ca2E1-ATP state. It would therefore be kept on the direct route to phosphorylation upon Ca2+ binding as shown in Figure 1. We conclude that the physiological cycle of SERCA should not include the Ca2E1 state as a functionally relevant intermediate. Instead the Ca2+ activation of SERCA, and probably also the E2 to E1 transitions of P-type ATPases, in general, should be regarded as the equilibrium between two compact states interchanging in smooth transition, represented by the E2(Tg)-AMPPCP and the Ca2E1-ADP:AlF4− structures as initial and final states, respectively.

Materials and methods

Purification and crystallization

Ca2+-ATPase was prepared from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) vesicles, isolated from rabbit fast twitch skeletal muscle (SERCA1a), and purified by extraction with a low concentration of deoxycholate, according to established procedures (Andersen et al, 1985). In order to produce E2-protein crystals, the purified membranes were solubilized by 35 mM octaethyleneglycol dodecylether (C12E8) in 100 mM MOPS-OH (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 80 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, in the presence or absence of 125 μM thapsigargin, and with or without 1 mM AMPPCP. The solubilization was followed by ultracentrifugation at 4°C for 35 min at 50 000 r.p.m. in a Beckman TLA-110 rotor. The protein was kept on ice overnight and then subjected again to ultracentrifugation for 15 min at 70 000 r.p.m. The supernatant, with a protein concentration of approximately 12 mg/ml, was >95% pure and was used directly for crystallization experiments by the vapor diffusion method in hanging drops.

Crystallization drops of 2+2 μl were formed by mixing protein solution and crystallization buffer consisting of 15% (w/v) PEG 2000 MME, 50 mM NaOAc, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 4% MPD. Large, single crystals grew over 2–3 weeks at 12°C. Crystals were cryoprotected by adding 20% glycerol to the reservoir followed by equilibration overnight by vapor diffusion. The square plate-shaped crystals were mounted directly from the mother liquor in bent nylon loops, which would typically orient the almost 600 Å long c-axes within 30° of the rotation axis of the goniostat. Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection and processing

Data sets were collected using synchrotron radiation (Table I). Data were processed and merged using the HKL package (Otwinowski, 1997) or XDS (Kabsch, 1993). The structures were readily solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov, 1997) and a monomer of the PDB deposition 1IWO (Toyoshima and Nomura, 2002) as a search model. Apparently, our E2(Tg) crystal forms possess higher symmetry of the unit cell than that of the PDB depositions 1IWO and 2AGV (P41212 versus P41) even though unit cell parameters and the crystal packing are essentially identical. Fobs[E2(Tg)-AMPPCP]−Fobs[E2(Tg)] isomorphous difference Fourier maps were used to locate the AMPPCP molecule and Mg2+ as well as conformational changes at the nucleotide binding site.

Model building and refinement

Model building was accomplished with the program O (Jones et al, 1991) and refinement was carried out with programs of the CNS package using maximum likelihood targets (Brunger et al, 1998). Rebuilt models were subjected to energy minimization followed by restrained atomic B-factor refinement. Bulk solvent correction and anisotropic scaling was used at later stages. Omit Fobs−Fcalc maps were inspected and revealed no interpretable features. The structures were validated with the CCP4 PROCHECK program (Laskowski et al, 1993). Statistics of the data collection, refinement, and model validations are shown in Table I. The coordinates of the two E2(Tg)-AMPPCP forms and the E2(Tg) form 2 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with entry codes 2C88, 2C8 K, and 2C8L respectively.

Biochemical assays

Nucleotide and Ca2+ binding. The binding properties of Ca2+-ATPase membranes (0.1–1 mg. protein/ml), treated with or without thapsigargin (10–20 μM), was measured by Millipore filtration by the double filter technique (Moller et al, 2002). ATP and MgATP binding by thapsigargin-bound or native ATPase in the E2 form was measured after addition of [C14]-ATP at concentrations varying from 2.5–100 μM nucleotide to media containing either (i) 100 mM Mops/Tris (pH 7.2), 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM EDTA, or (ii) media where 1 mM Mg2+ and 1 mM EGTA had replaced 1 mM EDTA. Aliquots (2 ml), containing 0.20 mg protein, were filtered through Millipore nitrocellulose (0.45 μm) double filters, without rinsing, and the amount of bound nucleotide calculated from the difference between the radioactive counts present in the upper and lower filter. In the Ca2+ binding experiments, the effect of thapsigargin was tested in buffers at various pH, and in the absence or presence of AMPPCP. In addition, the perfusion media contained 100 mM buffer either of Mes, adjusted to pH 6.0 with Trisbase, or of Mops/Tris (pH 7.2), or Tes/Tris (pH 8.0)). After deposition of 0.25 mg protein on the upper filter, these were perfused with 2 × 1 ml medium, containing 100 mM KCl, 1 mM Mg2+, 0.05 or 0.10 mM Ca2+ with [45Ca2+], and various concentrations of Ca2+ chelators to produce various free concentrations of Ca2+, 1 μM thapsigargin (for the thapsigargin reacted ATPase), absence or presence of 0.5 mM AMPPCP, and 100 mM buffer (either Mes/Tris (pH 6.0), or Mops/Tris (pH 7.2), or Tes/Tris (pH 8.0)). The amount of Ca2+ binding to the ATPase was calculated from the difference between radioactive counts in the upper and lower filter, with a correction for Ca2+ medium contamination of 0.005 mM. As Ca2+ chelator in the perfusion media, we used EGTA at pH 6.0 and 7.2, but BAPTA at pH 8.0 to avoid ‘erratic' pCa values (Forge et al, 1993a, 1993b), due to a too high dissociation constant for EGTA at pH 8.0, inappropriate for estimation of pCa values at this pH.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to JP Andersen B Vilsen and J Nyborg for valuable discussions, to B Holm and B Nielsen for technical assistance, and to M Esman for comments on the manuscript. Beam time at beam lines BL14.1 and BL14.2 at the BESSY facility and at beam lines BM14.1 and ID29 at the ESRF facility are acknowledged. We are particularly indebted to Uwe Müller (BESSY, BL14) and Martin Walsh (ESRF, UK BM14) for extensive assistance with data collection. This work was supported by grants from the Danish Medical Research Council, from the Danish Natural Science Research Council via the Center for Structural Biology and the Dansync program, from the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and from the University of Aarhus Research Foundation. PN is supported by a Hallas-Møller stipend of the Novo Nordisk Foundation. A PhD fellowship to ALJ was financed by the Lundbeck Foundation, and CO is the recipient of a stipend from the PC Petersen Foundation.

References

- Andersen JP, Lassen K, Moller JV (1985) Changes in Ca2+ affinity related to conformational transitions in the phosphorylated state of soluble monomeric Ca2+-ATPase from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 260: 371–380 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JP, Vilsen B (1992) Functional consequences of alterations to Glu309, Glu771, and Asp800 in the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 267: 19383–19387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Galperin MY, Koonin EV (1998) The catalytic domain of the P-type ATPase has the haloacid dehalogenase fold. Trends Biochem Sci 23: 127–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D 54 (Part 5): 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E (2002) Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 1115–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champeil P, Guillain F (1986) Rapid filtration study of the phosphorylation-dependent dissociation of calcium from transport sites of purified sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase and ATP modulation of the catalytic cycle. Biochemistry 25: 7623–7633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champeil P, Riollet S, Orlowski S, Guillain F, Seebregts CJ, McIntosh DB (1988) ATP regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Metal-free ATP and 8-bromo-ATP bind with high affinity to the catalytic site of phosphorylated ATPase and accelerate dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem 263: 12288–12294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen JD, McIntosh DB, Vilsen B, Woolley DG, Andersen JP (2003) Importance of conserved N-domain residues Thr441, Glu442, Lys515, Arg560, and Leu562 of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase for MgATP binding and subsequent catalytic steps. Plasticity of the nucleotide-binding site. J Biol Chem 278: 20245–20258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denmeade SR, Jakobsen CM, Janssen S, Khan SR, Garrett ES, Lilja H, Christensen SB, Isaacs JT (2003) Prostate-specific antigen-activated thapsigargin prodrug as targeted therapy for prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 990–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode L, Andersen JP, Leslie N, Dhitavat J, Vilsen B, Hovnanian A (2003) Dissection of the functional differences between sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) 1 and 2 isoforms and characterization of Darier disease (SERCA2) mutants by steady-state and transient kinetic analyses. J Biol Chem 278: 47877–47889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein-Ludwig U, Webb RJ, Van Goethem ID, East JM, Lee AG, Kimura M, O'Neill PM, Bray PG, Ward SA, Krishna S (2003) Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 424: 957–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Belda F, Kurzmack M, Inesi G (1984) A comparative study of calcium transients by isotopic tracer, metallochromic indicator, and intrinsic fluorescence in sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase. J Biol Chem 259: 9687–9698 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush B III (1987) Rapid release of 42K and 86Rb from an occluded state of the Na,K-pump in the presence of ATP or ADP. J Biol Chem 262: 11104–11115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge V, Mintz E, Guillain F (1993a) Ca2+ binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase revisited. I. Mechanism of affinity and cooperativity modulation by H+ and Mg2+. J Biol Chem 268: 10953–10960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge V, Mintz E, Guillain F (1993b) Ca2+ binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase revisited. II. Equilibrium and kinetic evidence for a two-route mechanism. J Biol Chem 268: 10961–10968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn IM (1984) The electrogenic sodium pump. Soc Gen Physiol Ser 38: 33–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillain F, Champeil P, Lacapere JJ, Gingold MP (1981) Stopped flow and rapid quenching measurement of the transient steps induced by calcium binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum adenosine triphosphatase. Competition with Ca2+-independent phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 256: 6140–6147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach W, Makinose M (1961) The calcium pump of the ‘relaxing granules' of muscle and its dependence on ATP-splitting.]. Biochem Z 333: 518–528 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua S, Inesi G, Nomura H, Toyoshima C (2002) Fe2+-catalyzed oxidation and cleavage of sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase reveals Mg2+ and Mg2+-ATP sites. Biochemistry 41: 11405–11410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inesi G, Ma H, Lewis D, Xu C (2004) Ca2+ occlusion and gating function of Glu309 in the ADP-fluoroaluminate analog of the Ca2+-ATPase phosphoenzyme intermediate. J Biol Chem 279: 31629–31637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47 (Part 2): 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W (1993) Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Cryst 26: 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Moss DS, Thornton JM (1993) Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J Mol Biol 231: 1049–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund S, Moller JV (1988) Biphasic kinetics of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and the detergent-solubilized monomer. J Biol Chem 263: 1654–1664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Inesi G, Toyoshima C (2003) Substrate-induced conformational fit and headpiece closure in the Ca2+ATPase (SERCA). J Biol Chem 278: 28938–28943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DB, Boyer PD (1983) Adenosine 5′-triphosphate modulation of catalytic intermediates of calcium ion activated adenosinetriphosphatase of sarcoplasmic reticulum subsequent to enzyme phosphorylation. Biochemistry 22: 2867–2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DB, Clausen JD, Woolley DG, MacLennan DH, Vilsen B, Andersen JP (2003) ATP binding residues of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Ann NY Acad Sci 986: 101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz E, Mata AM, Forge V, Passafiume M, Guillain F (1995) The modulation of Ca2+ binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase by ATP analogues is pH-dependent. J Biol Chem 270: 27160–27164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JV, Juul B, le Maire M (1996) Structural organization, ion transport, and energy transduction of P-type ATPases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1286: 1–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JV, Lenoir G, Marchand C, Montigny C, le Maire M, Toyoshima C, Juul BS, Champeil P (2002) Calcium transport by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Role of the A domain and its C-terminal link with the transmembrane region. J Biol Chem 277: 38647–38659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montigny C, Jaxel C, Shainskaya A, Vinh J, Labas V, Moller JV, Karlish SJD, le Maire M (2004) Fe2+-catalyzed oxidative cleavages of Ca2+-ATPase reveal novel features of its pumping mechanism. J Biol Chem 279: 43971–43981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara K, Miyashita N, Xu C, Toyoshima I, Sugita Y, Inesi G, Toyoshima C (2005) Structural role of countertransport revealed in Ca2+ pump crystal structure in the absence of Ca2+. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14489–14496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen C, Sorensen TL, Nielsen RC, Moller JV, Nissen P (2004) Dephosphorylation of the calcium pump coupled to counterion occlusion. Science 306: 2251–2255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski WMAZ (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology.Vol 276: Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A, In: Carter Jr CW, Sweet RM (eds), pp 307–326. New York: Academic Press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchornik G, Munson K, Goldshleger R, Shainskaya A, Sachs G, Karlish SJ (2002) The ATP-Mg2+ binding site and cytoplasmic domain interactions of Na+,K+-ATPase investigated with Fe2+-catalyzed oxidative cleavage and molecular modeling. Biochem 41: 11740–11749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart CM, Jencks WP (1982) Slow dissociation of ATP from the calcium ATPase. J Biol Chem 257: 5319–5322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RL, Hegyvary C, Kume S (1972) Activation by adenosine triphosphate in the phosphorylation kinetics of sodium and potassium ion transport adenosine triphosphatase. J Biol Chem 247: 6530–6540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JM, Goldshleger R, Munson KB, Sachs G, Karlish SJD (2001) Selective Fe2+-catalyzed oxidative cleavage of gastric H+,K+-ATPase: implications for the energy transduction mechanism of P-type cation pumps. J Biol Chem 276: 48440–48450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohoel H, Jensen AM, Moller JV, Nissen P, Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT, Olsen CE, Christensen SB (2006) Natural products as starting materials for development of second-generation SERCA inhibitors targeted towards prostate cancer cells. Biorg Med Chem 14: 2810–2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen TL, Moller JV, Nissen P (2004) Phosphoryl transfer and calcium ion occlusion in the calcium pump. Science 304: 1672–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N, Jencks WP (1984) Adenosine 5′-triphosphate at the active site accelerates binding of calcium to calcium adenosinetriphosphatase. Biochemistry 23: 5389–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strugatsky D, Gottschalk KE, Goldshleger R, Bibi E, Karlish SJD (2003) Expression of Na+,K+-ATPase in Pichia pastoris: analysis of wild type and D369N mutant proteins by Fe2+-catalyzed oxidative cleavage and molecular modeling. J Biol Chem 278: 46064–46073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strugatsky D, Gottschalk KI, Goldshleger R, Karlish SJD (2005) D443 of the N domain of Na+,K+-ATPase interacts with the ATP–Mg2+ complex, possibly via a second Mg2+ ion. Biochemistry 44: 15961–15969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Mizutani T (2004) Crystal structure of the calcium pump with a bound ATP analogue. Nature 430: 529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Nakasako M, Nomura H, Ogawa H (2000) Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 A resolution. Nature 405: 647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Nomura H (2002) Structural changes in the calcium pump accompanying the dissociation of calcium. Nature 418: 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Nomura H, Tsuda T (2004) Lumenal gating mechanism revealed in calcium pump crystal structures with phosphate analogues. Nature 432: 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlemann AC, Cameron A, Eckstein-Ludwig U, Fischbarg J, Iserovich P, Zuniga FA, East M, Lee A, Brady L, Haynes RK, Krishna S (2005) A single amino acid residue can determine the sensitivity of SERCAs to artemisinins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 628–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst 30: 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi S, Ogurusu T, Shigekawa M (1986) Factors influencing calcium release from the ADP-sensitive phosphoenzyme intermediate of the sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase. J Biol Chem 261: 9762–9769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]