Abstract

Spontaneously generated calcium (Ca2+) waves can trigger arrhythmias in ventricular and atrial myocytes. Yet, Ca2+ waves also serve the physiological function of mediating global Ca2+ increase and muscle contraction in atrial myocytes. We examine the factors that influence Ca2+ wave initiation by mathematical modeling and large-scale computational (supercomputer) simulations. An important finding is the existence of a strong coupling between the ryanodine receptor distribution and Ca2+ dynamics. Even modest changes in the ryanodine receptor spacing profoundly affect the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation. As a consequence of this finding, we suggest that there is information flow from the contractile system to the Ca2+ control system and this dynamical interplay could contribute to the increased incidence of arrhythmias during heart failure.

INTRODUCTION

The control and loss of control of Ca2+ wave initiation (regenerative propagation of intracellular Ca2+ release) are important for both normal and pathological excitation-contraction coupling (E-C coupling) in cardiac muscle. Mammalian atrial cells lack an extensive transverse tubule system (t-tubules), so an action potential triggers Ca2+ release only from the ryanodine receptor clusters (or Ca2+ release units, CRUs) directly coupled to the L-type Ca2+ channels on the surface sarcolemma (1,2) and at interior sites associated with the less developed transverse axial tubular system (2). Nonpropagating Ca2+ release limited to the sarcolemma surface would activate only a fraction of the myofibrils near the surface. However, an action potential can also initiate a centripetally propagating Ca2+ wave (1–4) that allows rapid activation of the myofilaments in the central core of the cell (2). The mode of Ca2+ release (propagating or nonpropagating) determines the rate and magnitude of contraction in atrial myocytes.

Mammalian ventricular cells, due to their extensive and well-organized t-tubules, do not use Ca2+ waves for normal E-C coupling, because an action potential triggers synchronous Ca2+ release throughout the cell. Nevertheless, spontaneously generated Ca2+ waves do occur in ventricular cells as in atrial cells (4–6). Spontaneous Ca2+ release or Ca2+ waves can elicit delayed afterdepolarization as the excess Ca2+ is removed from the cell via the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (7,8). A growing body of evidence also suggests that spontaneous waves may trigger cardiac arrhythmias (9–12). Hence, it is important to understand the factors that control the pathological generation of Ca2+ waves.

This article examines the factors that influence wave initiation using mathematical modeling and large-scale computational (supercomputer) simulations. Of particular interest is the relationship between the three-dimensional (3-D) CRU distribution and Ca2+ wave initiation. We used antibody labeling and confocal imaging experiments to measure the spacing of CRUs along the longitudinal axis of cardiac myocytes (longitudinal spacing, equivalent to the Z-disk spacing), within the Z-disk (transverse spacing), and described a newly found intercalated CRU on the cell periphery (13). In this article, we describe and explain how even subtle changes in the CRU spacing along any of these dimensions can profoundly influence the Ca2+ wave initiation.

An important finding of these studies on CRU spacing and Ca2+ wave initiation is that the state of the contractile system can profoundly affect the dynamics of the Ca2+ control system. This flow of information from the contractile to the Ca2+ control system is complementary to the information flow from the Ca2+ to the contractile system in the canonical E-C coupling paradigm. Hence, this newly found feedback loop suggests a continuous and circular flow of information between the electrical, Ca2+, and contractile systems, given the existence of feedback from the Ca2+ to the electrical excitation (see Bers (14) for review). Based on our results, we propose that the feedback from the contractile system to the Ca2+ control system may contribute, in part, to the increased incidence of arrhythmias in certain forms of heart failure and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

METHODS

In this section, a representation of the governing system of diffusion/reaction partial differential equations (PDEs) is presented along with a brief discussion of the numerical solution methods and the mathematical models that are used to implement the cardiac cell model. The PDEs that describe the diffusion and reaction of Ca2+ (C), the endogenous buffers (B), and fluorescent indicator (F) are essentially the same as described in our previous publications (15,16) except that now the number of spatial dimensions is three instead of two. We note that full 3-D simulations are required in this study to model the effects of the complex 3-D CRU distribution in cardiac myocytes measured by antibody labeling experiments (13). In addition, locally refined, highly resolved, unstructured meshes and temporal discretization are necessary for representation of the complex CRU distribution in space and time.

Briefly we present a generalized notation for the governing diffusion/reaction systems of equations for the cardiac cell model. This general notation allows us to present the essence of the finite element approximation that follows very compactly. The governing PDEs for multi-component diffusion mass transfer and nonequilibrium chemical reactions are given by

|

(1) |

where Ci is the concentration of species i, Di is a 3 × 3 diffusion mass transfer tensor that allows for anisotropic effects (in our model, this is a diagonal tensor), Si is the volumetric source term for species i, and NS is the total number of unknown concentrations in the simulation. A detailed description of the complete set of PDEs is presented in Appendix A. We present the equation for the free Ca2+ concentration here because it provides a useful reference for explaining the model and geometry.

|

(2) |

The Z-disks are in the xy plane and the longitudinal axis of the cardiac cell lies along the z axis. Diffusion (for both Ca2+ and fluorescent indicator) in the xy plane is assumed to be isotropic (Dx = Dy) and the diffusivity is assumed to be half of that along z (Dx = Dz/2 (17)). δ(·) is a Dirac delta-like function in the sense that the integral of the product of these functions and σ is the molar flux of Ca2+ (moles/s). δ(·) is nonzero at the CRU and zero elsewhere. The exact specification of δ(·) is given below in Numerical methods. S is a stochastic function that takes on the value of 1 (causing the CRU to “fire”) or 0 (turning the CRU off). The probability that a CRU at position (x,y,z) will fire in time t − Δt/2 < t < t + Δt/2 is P(C(x,y,z,t))Δt, where P is the probability of firing per unit time. P is given by

|

(3) |

as measured by Lukyanenko and Györke (18).

The source strength σ is the Ca2+ molar flux density and is given by σ = ISR/2F, where ISR is the Ca2+ current (in pA) through the CRUs and F is the Faraday constant. In 3-D, σ has a very simple interpretation: it is the flux density of Ca2+. In 2-D, however, σ is a line source and has units of mol/s/μm and a reasoned “fudge” factor had to be introduced to relate σ to the current ISR (16). No such factor is needed in 3-D.

The CRU currents, ISR, used in our simulations range from 10 to 25 pA. This range is based on several studies using various methods to estimate ISR. ISR, back-calculated from the size of sparks, ranges from 10 to 20 pA (15,19). Estimates based on ruthenium red inhibition of RyR2 (20) put the number of RyR2s underlying a spark at k > 10 and, therefore, ISR >5 pA, assuming single-channel current of 0.5 pA (21). Estimates based on spark amplitude variability give k > 18 and ISR ∼ 10 pA. (22). It is noted that the current magnitude underlying cardiac Ca2+ sparks remains a controversial issue to date. Based on the rate of rise of sparks, Cheng and co-workers estimated k between 1 and 3 (23,24). However, we have argued (13) that if k were small, then failure to trigger a spark would be high, which is at odds with the near certainty of eliciting sparks by depolarization (25). Moreover, sparks occurring under conditions that engender Ca2+ waves have larger amplitude and spatial size than those occurring under conditions where probability of Ca2+ waves is low (6). Since ISR increases rapidly with spark size (15), ISR values used for studying Ca2+ waves should be considerably larger than those for modeling sparks under quiescent conditions.

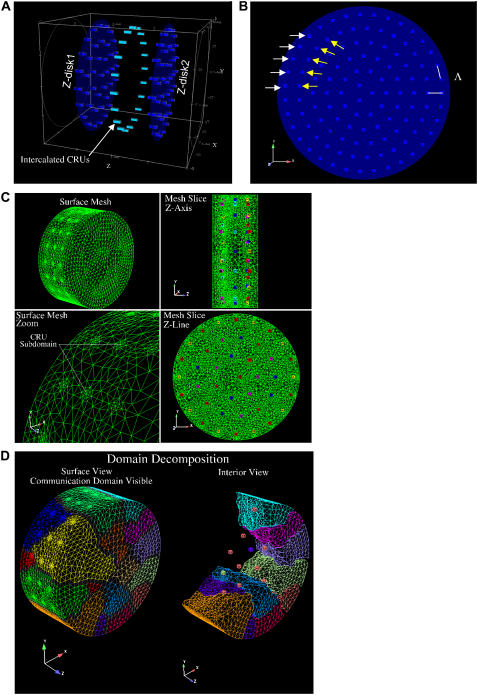

The model geometry of a single sarcomere, based on the experimentally measured RyR2 cluster distribution (13), is shown in Fig. 1 A. The dark blue circles mark the position of the Z-disks; the blue “bricks” are the CRUs on the Z-disk; and the cyan-colored bricks that lie between the Z-disks are the “intercalated” CRUs. Fig. 1 B shows the Z-disk in greater detail. The CRUs on the Z-disks are uniformly spaced Λ μm apart (0.8 or 1 μm) and are radially arranged in layers. CRUs on the periphery (white arrows) lie in the circle of radius r ≡ r0 = 4.5 μm. We refer to this layer of CRUs as the peripheral layer, or layer 0. The CRUs denoted by the yellow arrows lie on the circle whose radius is r = r1 = 4.5 μm − Λ. We shall refer to this layer of CRUs (r = r1) as the first inner layer or layer 1. In many simulations, n contiguous CRUs on layer 0 will be triggered to fire. The central CRU on layer 0 is simply the one that is in the middle of the group. The central CRU on layer 1 is the CRU that is closest to the central CRU on layer 0. Note that there might be two CRUs on layer 1 that are equidistant to the central CRU on layer 0. The distance between Z-disks is Lz (2 μm under control condition). For clarity, the plots along the z axis have been stretched out. The intercalated CRUs (cyan-colored bricks) are placed midway between the Z-disks and are present only on the periphery, at the same radial distance as the CRUs on layer 0 of the Z-disk. Their spatial separation is Λ, the same as the CRUs on the Z-disks. The central CRU on this ring of intercalated CRUs is the one that is closest to the central CRU on layer 0.

FIGURE 1.

Three-dimensional model geometry of the sarcomere and finite element mesh geometry and domain decomposition. (A) Dark blue disks are the Z-disks into which the CRUs (blue bricks) are embedded. The Z-disks lie in the xy plane and the longitudinal axis of the myocyte is along the z axis. The distance between the Z-disks is Lz. The intercalated CRUs (cyan bricks) are only on the cell periphery, forming a ring that is located midway between two Z-disks. (B) Detail of a single Z-disk. CRUs are circularly arranged with spacing Λ indicated by the white lines. See text for meaning of arrows. (C) A composite view of the unstructured tetrahedral FE mesh of the cardiac cell with two z-planes and a set of intercalated CRUs is shown. The upper left image presents the surface mesh of the cell section and the lower left image shows a close-up view of the unstructured mesh used to resolve the individual CRUs. The upper right image shows a projection of the mesh on an xz-slice plane through the domain. The lower right image shows the projection of the mesh on an xy-slice plane. The individual CRUs in these two images have been colored to make them more visible. (D) Composite view of the subdomain-to-processor assignment used to partition the mesh on 16 processors is shown. The left image shows subdomain-to-processor assignments by color. The partitioning assigns FE nodes to subdomains and then maps these subdomains to processors. The gray intersubdomain region indicates boundaries between processors for which communication of information takes place in the parallel FE code. The image on the right is a partial exploded view with the intersubdomains removed.

The simulation volume includes the two Z-disks and the region between them, plus flanking regions that extend an additional 1 μm. Zero-flux boundary conditions are imposed on the cylindrical boundary and the flat end caps. The zero-flux boundary condition is a natural choice for the cylindrical boundary since the cell membrane is a barrier for free Ca2+ diffusion. We used this boundary condition for the end caps for computational efficiency; an absorbing boundary would be more natural. However, test simulations using a larger flanking domain showed that the conclusions are not materially affected by the edge effects arising from this boundary condition.

Numerical methods

2-D simulations (finite-difference methods)

Simulations of the 2-D model equations were carried out using finite differences to approximate the derivatives, and solved using the method of lines, with the model as described previously (16).

3-D simulations (unstructured mesh finite-element methods)

Simulations of the full 3-D model with the complex distribution of CRUs was carried out using a Galerkin finite-element (FE) method as implemented in the MPSalsa transport/reaction simulation code (26). The system of NS reaction/diffusion equation is solved in bounded open region Ω in R3, with a sufficiently smooth boundary ∂Ω = ΓmUΓd over the time interval (0,ϒ). The formal Galerkin weak form of the governing reaction/diffusion system is derived as follows. First, we multiply Eq. 1 by a test function ψ from the appropriate space  (see Thomee (27)), which gives

(see Thomee (27)), which gives

|

(4) |

Using the divergence theorem we obtain the resulting weak form

|

(5) |

of the governing equations. A Galerkin finite-element formulation for these equations restricts this system to a finite dimensional subspace  . In our implementation, we use linear hexahedral and tetrahedral elements that have a formal order of accuracy of O(h2). To complete the description of the method, we define the approximation to the time derivative by a first- or second-order approximation based on a backward Euler or trapezoidal rule method, respectively. This discrete approximation forms a large sparse system of nonlinear algebraic equations. In the paragraphs that follow, we give a brief overview of the critical issues of spatial and temporal resolution of the diffusion/reaction system and the parallel nonlinear and linear solution methods that are employed to solve the FE system of equations. A more detailed discussion of the spatial and temporal accuracy of these methods applied to diffusion/reaction problems can be found in Ropp et al. (28).

. In our implementation, we use linear hexahedral and tetrahedral elements that have a formal order of accuracy of O(h2). To complete the description of the method, we define the approximation to the time derivative by a first- or second-order approximation based on a backward Euler or trapezoidal rule method, respectively. This discrete approximation forms a large sparse system of nonlinear algebraic equations. In the paragraphs that follow, we give a brief overview of the critical issues of spatial and temporal resolution of the diffusion/reaction system and the parallel nonlinear and linear solution methods that are employed to solve the FE system of equations. A more detailed discussion of the spatial and temporal accuracy of these methods applied to diffusion/reaction problems can be found in Ropp et al. (28).

Our implementation of the continuous Dirac delta function in space from Eq. 2 in our discrete model is a spatially localized source term applied in a CRU subdomain. This geometry requires resolution of multiple length scales for the representation of the small length scale distributed CRUs and the overall cardiac cell domain, which we accomplish via unstructured finite-element tetrahedral meshes. An example of this type of mesh is shown in Fig. 1 C for a single saromere. Clearly, to adequately represent the smallest length scales, i.e., CRUs, local refinement about the CRUs is required. However, away from the CRUs, it is computationally economical to increase the element size to represent the entire cell geometry and, hence, decrease the required number of elements in the simulation. In Fig. 1 C we also show a close-up of this local resolution of the unstructured FE mesh near the projection of the CRUs on the surface mesh. This advantage of an unstructured FE method over a structured mesh PDE approximation, is significant and makes solution of complex problems of this type tractable on modern parallel supercomputing hardware.

In general, the governing diffusion/reaction equations and the discrete approximations to these equations produce a stiff system with multiple timescales. The stiffness of these equations is produced by the discrete approximation to the diffusion operator and by the source term operator. To integrate this stiff system in a stable and efficient way, we employ fully implicit solution methods. These techniques allow the simulation to resolve the dynamical timescale of interest (in this case the firing of the CRUs and the subsequent diffusion wave front) while not requiring, for stability, the simulation to run at the fastest stiff timescales of the system. It has been recently shown that fully implicit methods can have significant advantages in stability and accuracy when compared to some common operator split or semi-implicit methods for a subset of diffusion/reaction systems (28,29). In the time integration of the cardiac cell system, a second-order (trapezoidal rule) method is used and the time-step size is held constant to resolve the firing of the CRUs and the subsequent diffusion wave front. In the CRU model described below, the probability of firing was set at 30%/ms. To adequately resolve this release we selected a time-step size of 0.01 ms or a probability of firing per time step of 0.003. Numerical experiments were used to determine that this integration procedure was accurate (relative error <1%, utilizing equilibrium concentrations measuring total production of CRU source terms as a norm) for the simulations that are presented in this article.

As presented above, the fully implicit FE approximation of the diffusion/reaction system produces a very large system of nonlinear algebraic equations. To solve these coupled systems we use Newton's method as a nonlinear solver and employ Krylov iterative solver techniques (conjugate gradient or generalized minimum residual (GMRES) method) with domain decomposition preconditioners to solve the linear systems at each substep. The decomposition and mapping of the FE domain (the cardiac cell) onto the parallel machine is accomplished by a graph partitioning method. Chaco (30), a general graph partitioning tool, is used to partition the FE mesh into subdomains and make subdomain-to-processor assignments. Chaco constructs partitions and subdomain mappings that have low interprocessor communication volume, good load balance, few message start-ups and only small amounts of network congestion. In Fig. 1 D, we present a sample partition of a cardiac cell mesh on 16 processors. In this figure, the color assignment of FE nodes is used to visualize the assignment to processors. In general, the partitioner assigns contiguous sets of elements to processors (see exploded view in B). Communication occurs across interprocessor boundaries to update information that is computed on neighboring processors. For a detailed description of parallel FE data structures and a discussion of the strong link between partitioning quality and parallel efficiency, see Hendrickson and Leland (30) and Shadid et al. (31). Finally, the domain decomposition preconditioners are based on parallel additive Schwarz domain decomposition methods (see, e.g., Smith et al. (32)) that use approximate incomplete LU solves on each subdomain. These preconditioners are used to efficiently solve the linear systems with a high degree of parallel scalability to thousands of processors. For a typical time step, this solution procedure requires one or two Newton steps and <10 linear iterations per Newton step.

The computations were performed on clusters at Sandia National Laboratories. A typical problem requires ∼200,000 unknowns per time step (number of nodes in geometry × number of species (calcium, fluorescent indicator, and protein buffers)). A 100-ms simulation requires 10,000 time steps. Depending on availability of compute nodes, where each node possesses two 1- to 3-GHz Pentium III or Pentium IV processors, we generally performed solutions on 4–16 nodes. Time to complete simulations ranged from 12 to 36 h, depending on the individual cluster's processor speed, excluding waiting time in the job scheduling queue.

Mathematical tools

The firing of a CRU is a stochastic process, so the outcome of a single simulation should not be viewed as representative of the archetypal behavior for a given set of parameters. An ensemble of repeated simulations is needed to obtain a more complete and accurate picture of the system's typical behavior. However, in some cases we can use the results of a single simulation to compute the probabilistic behavior of the system. This is possible in our model because the probability of CRU firing per unit time depends on the instantaneous cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. The probabilistic functions we will use are the waiting-time distribution w(x,y,z,τ,T), which is the probability of having to wait at least T ms starting from time τ before a CRU at (x,y,z) fires, and the probability density function φ(x,y,z,t,τ). For brevity, we henceforth drop the (x,y,z) dependency. w(T;τ) is given by

|

(6) |

where P(s) is the probability of spark firing per unit time at time s given in Eq. 3. This fundamental equation was derived in our earlier work (16), but here an explicit τ-dependence is included for studying synchronization. The probability density function (pdf) φ(T) is defined by

|

(7) |

where the explicit expression for φ(T;τ) comes from differentiation with respect to T.

Except when studying synchronization of Ca2+ release (see below), we will take τ to be 0 and we will drop the explicit reference to τ. The meaning of φ(T) can be clarified by noting that 1 − w(T) ≡ q(T) is the probability that an event will occur in time 0 < t < T or

|

(8) |

In other words, φ(T) is the pdf for q(T). We note that φ(T) is normalized; its integral from 0 to ∞ equals 1 follows from Eqs. 6 and 7. That w(0) = 1 follows from Eq. 6 and, intuitively, from the certainty that one needs to wait more than zero ms before an event (a CRU firing) to occur.

The waiting-time distribution (WTD) is defined for a single CRU. The WTD for N CRUs, w(T,N), is the product of the individual WTDs because the CRUs are assumed to act independently. Thus, w(T,N) and its pdf φ(T,N) are

|

(9) |

Note that the assumption of independence does not imply that the firing probability of a CRU is unaffected by the history of firings of other CRUs. The assumption of independence only means that there is no direct effect of one CRU upon another except through the agency of changes in Ca2+ concentration.

The N CRUs in the product are those that are closest to the ones that have fired on the adjacent ring of CRUs. For example, in Fig. 1 B, the five CRUs that have fired are indicated by the white arrows. The N = 5 CRUs on the adjacent ring that go into the calculation of Eq. 9 are those pointed to by the yellow arrows. Note that “closest” is defined in terms of the Euclidean distance; when a CRU on the inner layer is equally close to two or more CRUs on the outer layer, other CRUs are chosen so that the number of CRUs in the calculation always equals the number that have fired. Although this might seem arbitrary, this choice does not materially change w(T,N). To see this, consider a CRU that does not see a substantial change in the Ca2+ concentration but is included in the product. Because its WTD is essentially unity, it makes little contribution to the product.

The mean waiting time before at least 1 CRU fires is MWT.

|

(10) |

Note that MWT can also be interpreted as the mean time of the first CRU to fire. From this viewpoint we can then ask what is the mean waiting time for the second, third, Nth CRU to fire? These times characterize the synchronization of Ca2+ release. To calculate these times, we first note that, in this model, the probability that a CRU will fire depends only on its instantaneous ambient Ca2+ concentration and not on its history: CRUs have no memory of their previous states. Given N CRUs, the MWT for the first CRU to fire is given by Eq. 10, with τ = 0. If the first CRU fires at t = t1, then to calculate the MWT before the next CRU fires, we use Eq. 10, but now with τ = t1 and φ in Eq. 9 replaced by φ(s,N − 1), because the first CRU is no longer available to fire. We can apply this procedure iteratively to find the MWT between CRU firings for all N CRUs. An example of synchronization is given in Fig. 4 B (see Fig. 4).

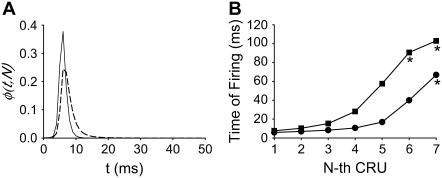

FIGURE 4.

Understanding why a wave is initiated when ISR = 16 pA but not when ISR = 13.4 pA. (A) Probability density function φ(t,N = 7) for ISR = 13.4 pA (dashed line) and 16 pA (solid line). φ(t,N) is not sufficiently sensitive to explain why a wave is initiated with ISR = 16 pA but not when ISR = 13.4 pA. (B) Synchronization curves show that five CRUs will fire within 11 ms of each other when ISR = 16 pA (circles) but it takes ∼50 ms for five CRUs to fire when ISR = 13.4 pA (squares). This long delay reduces the likelihood of wave initiation. The accuracy of the firing times in the synchronization curve depends on the accuracy of estimating the integral of φ(t,n) over infinite time. Since our simulation of the canonical Ca2+ distribution is limited to 100 ms, φ(t,n) is known only to 100 ms. When the Ca2+ concentration is high, the integral converges quickly to 1 and the firing time is accurate. When the integral is <0.8 the computed firing time is only a crude lower bound. Firing times that are not known accurately (integral <0.8) are marked with asterisks.

Studying Ca2+ wave initiation using “canonical pulses”

Computing the WTD requires an explicit expression of P (see Eq. 6) or, equivalently, the spatial and temporal distribution of Ca2+. We used the Ca2+ distribution generated by a canonical pulse (16). The canonical pulse is the simplest idealization of a distribution of Ca2+. The leftmost panels in Fig. 2 show the canonical pulse of Ca2+ generated by triggering eight contiguous CRUs on the periphery. Using this canonical Ca2+ distribution, we can calculate the average behavior of the system, in effect getting the equivalent of an infinite number of simulations from one. By using this canonical pulse, we can compute w(T,N) and φ(T,N), which we can readily compare for different parameters (such as ISR and Λ). These functions provide important insights into the mechanisms of Ca2+ wave initiation. The canonical pulse shown in Fig. 2 is meant to mimic the triggering of peripheral CRUs by an action potential. Later, we will use a canonical distribution to mimic a well-formed Ca2+ wave. To calculate w(T,N) and φ(T,N), we prevent other CRUs from firing by setting their Pmax to zero (see Eq. 3)

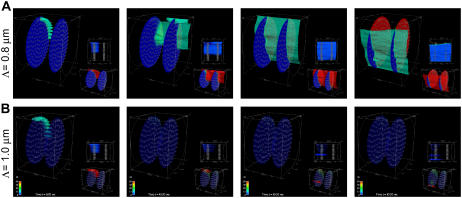

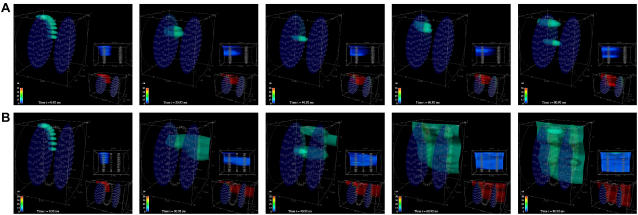

FIGURE 2.

Qualitative difference in Ca2+ dynamics resulting from a small change in CRU spacing. These snapshots are of two simulations that used identical parameters and initial conditions, except that the CRU spacing is Λ = 0.8 μm in A and 1.0 μm in B. A Ca2+ wave is initiated when Λ = 0.8 μm but not when Λ = 1.0 μm. In this and subsequent figures, each image is divided as follows. The large image on the upper left is an oblique view of the sarcomere, which includes a 15-μM Ca2+ isoconcentration surface. The smaller image near the bottom right shows the Ca2+ concentration over the smaller range of 0.1–2 μM, and shows the isoconcentration surface at 2 μM. The small image near the middle of the right-hand side is a side view of the sarcomere. A suite of isoconcentration surfaces at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 μM are shown. The side view is especially helpful for understanding how CRUs on different Z-disks interact. The color bar ranges from 0.1 to 50 μM for the large image and from 0.1 to 2 μM for the lower right image. Simulation times are 0.92, 45.92, 65.92, and 85.92 ms (left to right). Simulation parameters: ISR = 13 pA, Lz = 1.6 μm; other parameters are given in Appendix A.

RESULTS

In this section, we will study the important factors that influence the Ca2+ wave generation and examine the relationship between Ca2+ waves and the CRU distribution in 3-D. First, we will develop the important concepts and tools along with analyzing the effect of transverse spacing of CRUs on Ca2+ waves. Next, we will use these concepts and tools to analyze the effect of intercalated CRUs on Ca2+ waves. Finally, we will apply the analysis method to examine the influence of CRU longitudinal spacing on Ca2+ waves and study the effect of shortened sarcomere length on altering the Ca2+ dynamics, possibly linking these to increased propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ waves and arrhythmias in certain forms of heart failure and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Please see Figs. 2, 6, 7, 9, and 10 for snapshots of evolving Ca2+ dynamics. Movies of these simulations are available in Supplemental Materials.

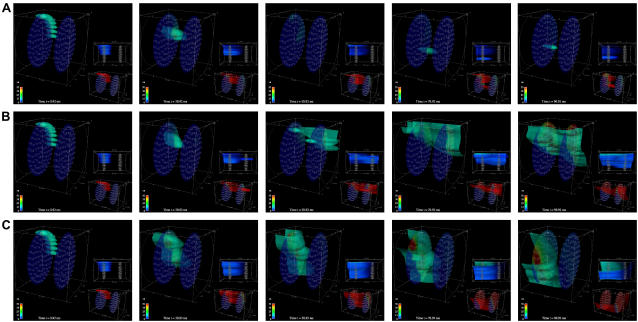

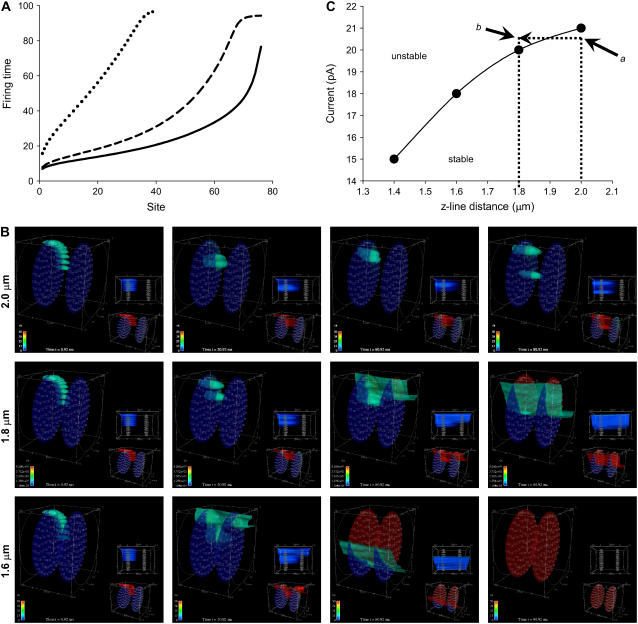

FIGURE 6.

Cooperative Z-disk interactions. CRUs on Z-disk 2 (on the right) are inactive (Pmax = 0) in A and active (Pmax = 0.3/ms) in B. Otherwise, the simulations are identical. Because Ca2+ released from CRUs on one Z-disk can increase the probability of firing of a CRU on the other Z-disk, this regenerative feedback reinforces the nascent wave and a stable wave propagates across the Z-disks in B. In A, this cooperative interaction is absent and no wave forms. (C) The CRUs on Z-disk 2 are inactive but a wave forms because the current has been increased from ISR = 21 pA (in A and B) to 25 pA. All simulations are started with the canonical pulse. The color bar ranges from 0.1 to 50 μM for the large image and from 0.1 to 2 μM for the lower right image. Snapshots are taken at 0.92, 30.92, 50.92, 70.92, and 90.92 ms.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of intercalated CRUs (i-CRUs). i-CRUs are absent in the simulations of A. When the current is ISR = 20 pA (A), a wave is not initiated. In the absence of i-CRUs the minimum current needed to initiate a wave is ∼21 pA (not shown). The current needed to initiate a wave is significantly reduced (to ∼15 pA) when i-CRUs are present (B). The color bar ranges from 0.1 to 50 μM for the large image and from 0.1 to 2 μM for the lower right image. Snapshots are taken at 0.92, 20.92, 40.92, 60.92, and 80.92 ms. Simulation parameters: Lz = 2.0 μm, Λ = 1.0 μm, others standard.

FIGURE 9.

A small decrease in sarcomere length greatly increases Z-disk interaction. (A) Synchronization curves as functions of sarcomere spacing (Lz) for Lz = 2.0 μm (dotted line), Lz = 1.8 μm (dashed line), and Lz = 1.6 μm (solid line). Simulation parameters: ISR = 20 pA, Λ = 1.0 μm, others standard. (B) These three simulations used identical parameters and initial conditions, except that the Z-disk spacing was 2.0 μm (upper), 1.8 μm (middle), and 1.6 μm (lower). Closer Z-disk spacing allows greater regenerative interaction of CRUs on adjacent Z-disks, thereby increasing the likelihood of Ca2+ wave generation. The color bar ranges from 0.1 to 50 μM for the large image and 0.1 to 2 μM for the lower right image. Snapshots are taken at 0.92, 20.92, 60.92, and 80.92 ms. Simulation parameters: ISR = 20 pA, Λ = 1.0 μm, others standard. (C) Currents needed to initiate a Ca2+ wave as a function of Z-disk spacing. All simulations were started with the canonical pulse (eight contiguous CRUs on layer 0 firing at t = 0). Currents were varied until a Ca2+ wave was initiated within 100 ms of the start of the pulse. For a given Z-disk separation, if ISR is below the curve the probability of wave initiation is low (e.g., point a) and the system is stable. If ISR remains constant but the Z-disk separation shortens to the extent that ISR moves above the curve then wave initiation is likely (e.g., point b) and the system becomes unstable. Simulation parameters: Λ = 1.0 μm, the rest are standard.

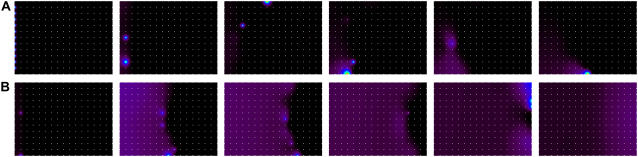

FIGURE 10.

Initiation versus support of Ca2+ waves. In these 2-D simulations the initial conditions were chosen to mimic either an action-potential-triggered CRU firing (A) or a well-formed Ca2+ wave (B). White dots mark the positions of the CRUs. Simulation parameters:ℓx = ℓy = 1 μm (see Fig. 6 A for definition of spacing parameters), ISR = 11 pA, others standard.

Effect of transverse spacing of CRUs on Ca2+ waves: a surprise

Our previous modeling study (15) has shown that the initiation and propagation of Ca waves depends critically on the spacing of the CRUs. Based on the work of Parker et al. (17), our earlier 2-D modeling work on ventricular cells (16) assumed a CRU transverse spacing (Λ) of 0.8 μm. Our initial 3-D simulations also used Λ = 0.8 μm. Using our novel method for getting improved resolution of CRU spacing in the transverse plane, we found that the transverse spacing of CRUs is 1.05 μm in the ventricular and 0.97 μm in the atrial myocytes (13). We did not expect to see qualitatively different dynamics in making the seemingly small change from Λ = 0.8 μm to Λ = 1.0 μm. We were, however, very surprised. Fig. 2 shows two simulations that were identical except for the spacing of the CRUs. The leftmost panels show nine peripheral CRUs on the left-hand Z-disk firing at t = 0 to simulate triggering by an action potential; this is the canonical pulse. For Λ = 0.8 μm (Fig. 2 A), the activation spreads to the next Z-disk and a Ca2+ wave is initiated and propagates across the two Z-disks. However, when Λ = 1.0 μm (Fig. 2 B), the canonical pulse fails to initiate a Ca2+ wave. (Ca2+ waves are defined operationally based on the shape of the time-to-target plots described in Kirk et al. (2).) To understand how a seemingly small change in CRU spacing has such a large effect on Ca2+ wave initiation, we studied how waves are initiated and propagated in a simpler 2-D system.

Important factors that influence Ca2+ wave initiation

Our efforts to understand the causes for this great sensitivity to Λ have given us new insights into the important factors that influence Ca2+ wave initiation and propagation. The basic insights gained here will reappear later when we examine the effects of CRU distributions in other dimensions, the intercalated CRUs, for example. Therefore, the next few sections will be devoted to developing the general strategy that we used for examining how Λ influences Ca2+ wave initiation.

Separation distance

To understand the basis for this great sensitivity of wave initiation on Λ, we needed to be able to examine the Ca2+ concentration at any point in space. We could do this much more easily in 2-D than in 3-D because of the much simpler 2-D computational mesh (uniform square cells versus tetrahedral or hexahedral elements). As will be shown below, the 2-D and 3-D systems share the same qualitative behavior.

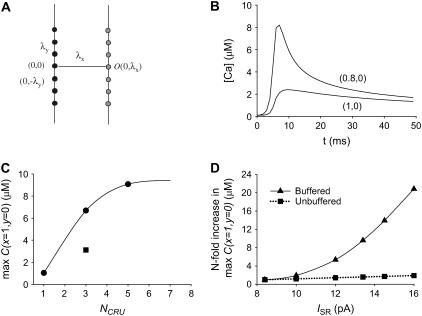

A schematic of the 2-D simulation geometry is shown in Fig. 3 A. The CRUs on the boundary (x = 0, black circles) are spaced ℓy apart and the Ca2+ concentration is measured at observation points (gray circles) at x = ℓx, y = 0, a horizontal distance of ℓx from the boundary. The simulations start off with N = 7 CRUs on the boundary firing at t = 0. Fig. 3 B shows the Ca2+ concentrations at observation points (x = 0.8, y = 0) and (x = 1, y = 0). Note the fourfold decrease in peak Ca2+ when the observation point increases by just 0.2 μm.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of CRU spacing, number of firing CRUs, and current on Ca2+ concentration in 2-D. (A) Geometry of the 2-D lattice. The firing CRUs (black dots) are on the line x = 0; they are spaced λy apart. The observation point O (gray dot), where the Ca2+ concentration is measured, is at x = λx, y = 0. The Ca2+ concentrations at the other observation points are used in a later figure. (B) Ca2+ concentration when the observation point is λx = 0.8 or 1 μm from the line of seven firing CRUs, which are spaced λy = 0.8 μm apart. The modest 20% reduction in λx results in a fourfold increase in peak Ca2+ concentration at O. (C) Maximum Ca2+ concentration at O as a function of the number of firing CRUs. The square gives the Ca2+ concentration that would be seen if no Ca2+ buffers were present and a single CRU produced the concentration shown. (D) n-fold change in peak Ca2+ concentrations at O as a function of Ca2+ current. The squares show the n-fold change in Ca2+ concentration that would be seen if Ca2+ buffers were absent.

These plots illustrate the important point that the free Ca2+ concentration is extremely sensitive to changes in separation distance between the source(s) and observation point. This extremely steep sensitivity cannot be understood in terms of linear diffusion. Making the approximation that M mol of Ca2+ are instantaneously deposited at the source point, then the Ca2+ concentration at a distance r (see Appendix A of Izu et al. (16) for the general case, where Ca2+ is delivered at a finite rate) is  , which achieves its maximum value at t = r2/(2D). This 1/r2 dependency is not strong enough to account for the sensitivity we observe. For example, in a linear system the ratio of peak Ca2+ concentrations at r = 0.8 and 1 μm would only be (1/0.8)2/(1/1)2 = 1.56, not the observed factor of 4 in the buffered system.

, which achieves its maximum value at t = r2/(2D). This 1/r2 dependency is not strong enough to account for the sensitivity we observe. For example, in a linear system the ratio of peak Ca2+ concentrations at r = 0.8 and 1 μm would only be (1/0.8)2/(1/1)2 = 1.56, not the observed factor of 4 in the buffered system.

Superadditivity

The steep dependence of the free Ca2+ concentration on separation distance arises from the presence of large quantities of Ca2+ buffers, both endogenous and exogenous (including the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator). Ca2+ buffers give rise to the phenomenon that we call “superadditivity” (see Izu et al. (16) and Appendix B). In the absence of buffers or when the buffers are completely saturated, the change in the free Ca2+ concentration is linearly related to the number of moles of Ca2+ added. In an unsaturated buffered system, with each addition of δn moles of Ca2+, there is an ever greater increase in the change of the free Ca2+ concentration because of the ever decreasing number of free-buffer binding sites available to bind Ca2+. A formal definition of superadditivity is given in Appendix B and we show how this nonlinear behavior can be understood from an equilibrium analysis. The superadditive behavior of buffered systems means that the free Ca2+ concentration increase due to two Ca2+ sources is larger than a simple addition from two sources. To illustrate this phenomenon, Fig. 3 C shows the maximum concentration at (x = 1 μm, y = 0) for different numbers of CRUs. Note that for NCRU = 3, the maximum concentration is more than six times the maximum concentration obtained for a single CRU. In a linear system, the corresponding maximum concentration is <3 times that for a single CRU (square). (The concentration is less than threefold greater because addition is weighted by the distance between the source and the observation point; see Eq. 3 of Izu et al. (16).)

Superadditive effects apply not only to the number of CRUs but also to the current amplitude (ISR) of the CRU. Fig. 3 D shows that the ratio of the maximum value of C at (x =1 μm, y = 0) relative to its value for ISR = 8.4 pA increases nonlinearly as ISR varies in a buffered system (triangles). In a linear system (squares), the ratio is directly proportional to the magnitude of the current (see Eq. 3 of Izu et al. (16)). When ISR changes from 8.4 to 20 pA, the approximately twofold change in maximum Ca2+ concentration in the linear unbuffered system is almost imperceptible on the scale needed to accommodate the 20-fold change in the nonlinear buffered system. The important point illustrated by this graph is that even small changes in source current can effect large changes in the free Ca2+ concentrations in buffered systems and consequently Ca2+ wave initiation and propagation.

Synchronization

A general definition of a Ca2+ wave front is an approximately synchronous firing of CRUs that recapitulates the firing pattern at an earlier time occurring on a well defined locus of points. Therefore, if the firing of N CRUs on the periphery of the Z-disk is to initiate a wave, then ∼N CRUs on the adjacent layer should fire at about the same time for a wave to progress. This notion of synchronicity is captured by the iterative computation of the WTD, w(T,n), as explained in Methods (note that n is not necessarily N).

In our previous work (16), we used φ(t,N) as a predictor of wave initiation. The idea behind its use is that wave propagation implies a modicum of predictability of Ca2+ spark firing, and the breadth of φ(t,N) is inversely related to the uncertainty of when a Ca2+ spark will occur. When φ(t,N) is sharply peaked (Fig. 4 A, solid line) there is little uncertainty about when a Ca2+ spark will occur (in this case, ∼6 ms after the canonical pulse), suggesting that a Ca2+ wave will be initiated. However, sometimes φ(t,N) is not sensitive enough to accurately predict wave initiation. For example, the two φ curves in Fig. 4 A are similar, yet a wave is initiated with ISR = 16 pA (solid line) but not with ISR = 13.4 pA (dashed line). The reason that φ, by itself, is not sensitive enough is that it generates the WTD for only the first Ca2+ spark occurrence. Since the Ca2+ wave front involves many Ca2+ sparks, a better indicator of wave initiation is the synchronization curve. The synchronization curve is the WTD of the first, second, …nth Ca2+ spark occurrence (Fig. 4 B). For both currents, the first spark occurs at about the same time, ∼6 ms after the canonical pulse, in agreement with the time the φ curves attain their peak. However, for ISR = 16 pA (solid line), the synchronization curve is initially almost flat because the first five CRUs fire within 10 ms of each other; they are almost synchronous. On the other hand, when ISR = 13.4 pA (dashed line), CRU firing is asynchronous; the fourth and fifth CRUs fire 20 and 50 ms, respectively, after the first. It is this lack of synchronous firing that causes the failure of a wave to be initiated.

Large-scale cooperative CRU interactions

One of the most important insights derived from this study is that cooperative interactions of CRUs on adjacent Z-disks and intercalated CRUs significantly increase the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation. To see how important these large-scale cooperative CRU interactions are, we first establish the reference state: the isolated Z-disk.

Initiation of Ca2+ waves on a single Z-disk: 3-D simulations

We wanted to determine whether the factors we found to be important for the initiation of waves from the 2-D simulations are also important in 3-D. The 2-D simulations are analogs for events on a single Z-disk. Therefore, in the following simulations only a single Z-disk is active (Pmax for all of the CRUs on the second Z-disk are set to zero) and intercalated CRUs are absent.

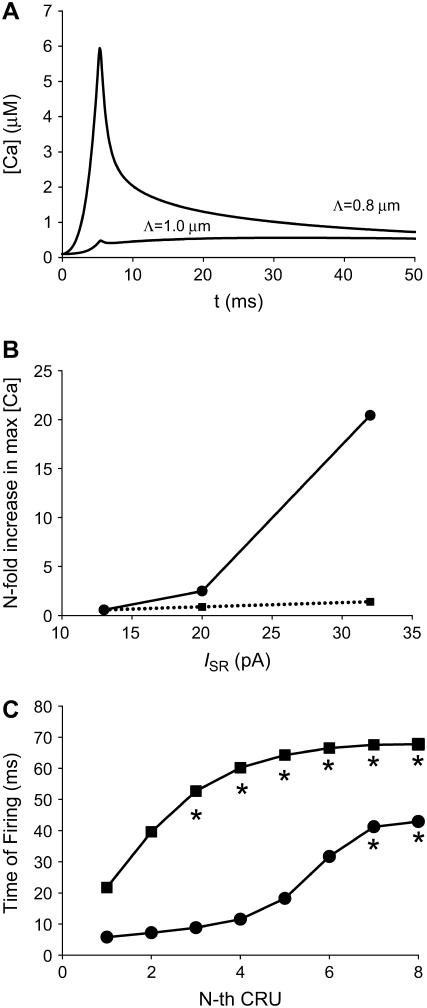

As in the 2-D simulations, we find that there is a very steep Ca2+ concentration gradient as Λ changes from 0.8 to 1.0 μm. Fig. 5 A shows the Ca2+ concentration measured at the CRU that sees the largest peak Ca2+. There is an 1100% increase (0.48 vs. 5.95 μM) in the maximum Ca2+ concentration as Λ decreases 20% from 1.0 to 0.8 μm. Note that although the plots in Figs. 5 A and 3 B are qualitatively similar, they are not exactly comparable, because in Fig. 3 B, the CRU packing density was fixed (ℓy = 0.8 μm) and only the distance between adjacent layers (ℓx = 0.8 or 1.0 μm) was changed. In the 3-D calculations, Λ changes both the packing density and interlayer spacing. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the WTDs are very sensitive to changes in the spacing of CRUs.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of CRU spacing and current in 3-D. (A) Ca2+ concentration measured at the central CRU on layer 1 (see Methods for definition) when eight contiguous CRUs fire simultaneously on layer 0. The peak Ca2+ concentration is 12-fold higher when Λ = 0.8 μm than when Λ = 1.0 μm. (B) n-fold increase in peak Ca2+ concentration at central CRU for different ISR. The dashed line shows the increase that would be seen in an unbuffered system. (C) Synchronization curves for ISR = 20 pA (squares) and 32 pA (circles). Asterisks have the same meaning as in Fig. 4.

Also similar to the 2-D case is the rapid increase in the maximum Ca2+ concentration seen by the central CRU with ISR (Fig. 5 B, solid line). The effect of superadditivity is evident from the comparison with the expected values for an unbuffered linear system (dotted line).

To estimate the current needed to initiate a Ca2+ wave, we computed synchronization curves for ISR = 32 pA (Fig. 5 C, circles) and ISR = 20 pA (Fig. 5 C, squares). When ISR = 32 pA, the MWT for the first CRU to fire (after the start of the canonical pulse) is ∼6 ms and that the first five CRUs fire within 13 ms. By contrast, when ISR = 20 pA, it takes ∼22 ms before the first CRU fires and subsequent CRUs fire much later. Although the values in the figure are lower bounds for CRU number >1 (see figure caption for explanation), it is sufficient to show that for ISR = 20 pA, the firing is asynchronous, so wave initiation is unlikely. The full simulations bear out these predictions. We find that a wave is readily initiated for ISR = 32 pA, but not when ISR = 21 pA (data not shown).

Because we have set up these 3-D simulations to be analogous to the 2-D simulations, it is not surprising that these results reinforce what we found in the 2-D studies, namely, that Ca2+ wave initiation is sensitive to CRU separation, superadditive effects, and synchronization of firing. Henceforth, we will focus on 3-D simulations that allow us to model the 3-D distribution of the CRUs in cardiac cells more realistically and reveal more complex interactions between CRUs.

Cooperative Z-disk interactions

The next level of complexity that we introduce is a second Z-disk. Fig. 6 shows two simulations that are identical (ISR = 21 pA) except that the CRUs on the second Z-disk (the one on the right, which we will call Z-disk 2) were either inactive (Fig. 6 A) or active (Fig. 6 B). When the CRUs are inactive, the Z-disk is functionally absent as it presents no diffusional barrier to Ca2+; in the figure, Z-disk 2 is present just for illustration. No wave is initiated when the CRUs of Z-disk 2 are inactive (Fig. 6 A). When the CRUs of Z-disk 2 are present, however, a wave is initiated (Fig. 6 B). In this case, the firing CRUs on the left-hand Z-disk (Z-disk 1) elevate the ambient Ca2+ concentration of the CRUs on Z-disk 2, increasing their firing probability. The firing of CRUs on Z-disk 2, in turn, increases the ambient Ca2+ concentration of Z-disk 1's CRUs, thereby increasing their firing probability. This regenerative feedback between CRUs of the two neighboring Z-disks stabilizes the nascent wave and increases the probability of wave initiation.

In the absence of cooperative Z-disk interactions (when CRUs of Z-disk 2 are inactive), the CRU current needs to be increased to ∼25 pA to initiate a wave (Fig. 6 C). Also, although it is not evident in these snapshots, the wave in Fig. 6 C propagates in a jerky fashion, whereas the wave in Fig. 6 B propagates smoothly (see movies in Supplemental Materials). Thus, not having CRUs on the adjacent Z-disk exacts a cost of ∼4 pA to initiate a wave. These results demonstrate the important point that the interaction of CRUs of adjacent Z-disks reduces the current required to initiate and support Ca2+ waves.

Intercalated CRUs

The “intercalated” RyR2s are located approximately midway between the Z-disks on the cell periphery (mean distance to Z-disk = 0.97 ± 0.42 μm in ventricular cells and 0.92 ± 0.38 μm in atrial cells) but not in the interior of the cell (13). To explore the effect the intercalated CRUs have on wave initiation we carried out simulations with and without the intercalated CRUs (Fig. 7). All simulations start off with the canonical pulse (0.92 ms) and CRUs on both Z-disks are active. In the absence of intercalated CRUs, a current of ISR = 20 pA is not sufficient to initiate a wave (Fig. 7 A), and ∼21 pA is needed to initiate a wave (Fig. 6 B). When the intercalated CRUs are present, however, a current of just 15 pA is enough to initiate a robust wave (Fig. 7 B). Therefore, the intercalated CRUs significantly reduce the current needed to initiate a wave.

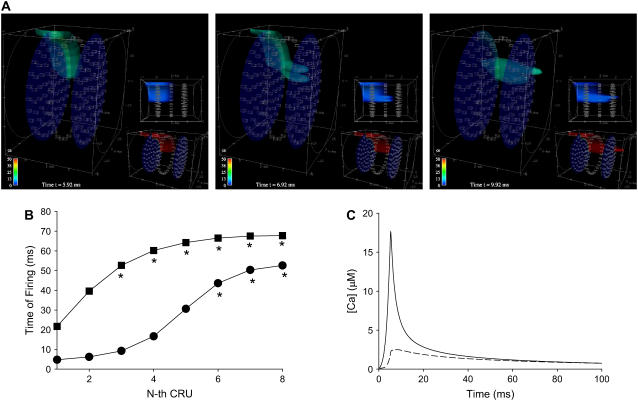

To understand how the intercalated CRUs reduce the current needed to initiate a wave, let us compare Ca2+ signal propagation within a Z-disk and between Z-disks. Fig. 8 A shows the Ca2+ distribution at t = 5.92 ms, the end of the canonical pulse (left). At t = 6.92 ms, two intercalated CRUs fire (middle), and at t = 9.92 ms, the first CRU on Z-disk 2 fires (right). Surprisingly, the first nontriggered CRU on Z-disk 1 fires much later, at 16.92 ms. These particular firing times are not statistical anomalies as they are close to the calculated firing times given in Fig. 8 B. The mean time for the first intercalated CRU firing (circles) is 4.8 ms, whereas the corresponding time for CRUs on Z-disk 1 is 21.7 ms (squares). Notice that the synchronization curve for the intercalated CRUs is initially almost flat, meaning that two or even three intercalated CRUs would fire almost simultaneously. This happened to be the case in this simulation where two intercalated CRUs fired at t = 6.92 ms. The intercalated CRUs are activated earlier because they see a larger and earlier rise of Ca2+ (Fig. 8 C, solid line) than the layer-1 CRUs on Z-disk 1 (Fig. 8 C, dashed line) because of the 2:1 anisotropic diffusion favoring faster flow along the z axis (longitudinally) over the transverse plane (within the Z-disk). (See Methods for definitions of layers and distances.)

FIGURE 8.

Intercalated CRUs act as relay stations. (A) The canonical pulse ends at 5.92 ms (left panel), and 1 ms later (at 6.92 ms, center panel), two intercalated CRUs fire. Their firing is seen more clearly in the side view of the sarcomere (center panel, inset, right-hand side of image). The first CRU on Z-disk 2 fires at 9.92 ms (right panel). (B) Synchronization curves for the i-CRUs (circles) and for the CRUs on Z-disk 1 (squares). Although the CRUs on layer 1 of Z-disk 1 and the i-CRUs are the same distance from the triggered CRUs (1 μm), the expected times for the i-CRUs to fire are substantially shorter than for the layer-1 CRUs (for example, 4.8 ms vs. 21.7 ms for the first CRU to fire). The reason for this difference is shown in the curves of C, which show the Ca2+ concentration seen by the central i-CRU (solid line) and the central CRU on layer 1 (dashed line). Simulation parameters: Lz = 2.0 μm, Λ = 1.0 μm, ISR = 15 pA, others standard.

Due to the fast diffusion in the z-direction, the firing of the intercalated CRUs can rapidly trigger peripheral CRUs on Z-disk 2. Indeed, the first peripheral CRU on Z-disk 2 fires at 9.92 ms, 7 ms before a CRU in layer 1 of Z-disk 1 fires, despite the fact that the CRUs on Z-disk 2 are about twice as far away. Therefore, the intercalated CRUs serve to link the dynamics of the adjacent Z-disks even more strongly than the cooperativity described in the previous section. The presence of intercalated CRUs causes Ca2+ waves to be initiated more rapidly and increases the velocity of the waves across the plane of the Z-disks (data not shown).

Z-disk interactions: sarcomere spacing variation

We have seen how CRUs on the different Z-disks reinforce each others' activities, making it easier for a wave to be initiated. In this section, we again consider how the activities of CRUs on one Z-disk affect those on an adjacent Z-disk but now focus on examining the strength of interaction as the sarcomere spacing varies. Of interest here is the relationship between sarcomere spacing and the probability of wave initiation. It is important to understand this relationship because it tells us how the mechanics of contraction affects Ca2+ dynamics.

Effect of shortening sarcomere length

To study the relation between sarcomere length and Ca2+ wave initiation, we forced all CRUs on one Z-disk (Z-disk 1) to fire, and, using the resultant Ca2+ concentration distribution, computed the probability of CRU firing on the adjacent Z-disk (Z-disk 2), that is, 2.0, 1.8, or 1.6 μm from Z-disk 1. The synchronization curves (Fig. 9 A) show the strong effect of sarcomere spacing on CRU activity. The synchronization curve for Lz = 1.6 μm (solid line) starts off almost flat, meaning that many CRUs fire almost simultaneously. The first 10 CRUs fire within 4.5 ms of each other. When Lz = 1.8, the first 10 CRUs fire within 6.4 ms of each other (dashed line). However, when Lz = 2.0 μm, the first 10 CRUs to fire are spread out over 23 ms (dotted line). In other words, the firings become asynchronous. This broad distribution in firing times is reflected in the steep slope of the Lz = 2.0 μm synchronization curve.

These results show that even a modest reduction in sarcomere spacing from 2.0 to 1.8 μm causes a tremendous increase in the ability of CRUs on adjacent Z-disks to increase each others' activities. The consequence of this reciprocating influence is that it is easier to initiate waves as illustrated in Fig. 9 B. Three simulations were carried out that are identical except for the distance between the Z-disks. Eight contiguous CRUs on the periphery of Z-disk 1 are forced to fire at t = 0 (leftmost images). With the Z-disks separated by Lz = 2 μm, the Ca2+ concentration increase seen by CRUs on Z-disk 2 is sufficiently low that no CRU fired and no wave was initiated (upper panel). When the Z-disk spacing is reduced to Lz = 1.8 μm (middle panel), the rise in the Ca2+ concentration resulting from CRUs on Z-disk 1 firing is now sufficiently high at Z-disk 2 that CRUs on Z-disk 2 fire. Their firing, in turn, increases the likelihood of CRUs on Z-disk 1 to fire. This reciprocal interaction gives rise to a well formed wave front emerging at around t = 60 ms. The interactions are even stronger when Lz = 1.6 μm (lower panel) and the wave front begins forming even earlier, at ∼40 ms.

Currents needed to initiate a wave as Z-disk spacing changes

Of further interest is the interplay between the Z-disk spacing and the Ca2+ current in initiating a wave. We determined the relationship between the minimum current needed to trigger a wave and the Z-disk spacing is roughly linear (Fig. 9 C). The current versus z-distance curve in Fig. 9 C separates this parameter space to stable and unstable zones. In the unstable zone where the current is large and z-distance is small, the system becomes unstable and a wave is initiated. Conversely, when the current is small and z-distance is large, the system is stable and wave initiation is unlikely.

Initiation versus support of wave propagation

It is important to distinguish between conditions that can initiate wave propagation from those that can support wave propagation. The simulations in Fig. 10 illustrate this distinction. Both simulations use identical parameters but differ in the initial conditions. In the first simulation (Fig. 10 A), the Ca2+ concentration is 0.1 μM everywhere, with endogenous and exogenous buffers in equilibrium. As an initial stimulus, all CRUs on the left edge are forced to fire at t = 1 ms. We see that this stimulus fails to initiate a wave (time flows from left to right). In Fig. 10 B, we set up the initial stimulus as a well formed wave by raising the Ca2+ concentration between 0 ≤ x ≤ 1.5 μm to 10 μM, whereas “in front” of the wave (x > 1.5 μm) the Ca2+ concentration is 0.1 μM, with all buffers in equilibrium with the Ca2+ at every point. In this case, the wave continues to propagate throughout the domain (to x = 16 μm), showing that these conditions can support wave propagation but, by themselves, cannot initiate wave propagation. The reason wave propagation can be sustained after the wave front is formed is because there is a large reservoir of Ca2+ behind the wave that can keep the Ca2+ concentration at the front high long enough to trigger Ca2+ release from the next set of CRUs and thereby maintain propagation.

The explanation for propagation might seem circular—positing the existence of a wave to continue a wave—but this circularity is broken if there is heterogeneity in the cell. For example, there may be a region where the sarcomeres are close together (say 1.6 μm apart), which can be a site for wave initiation. Once the wave is initiated, it can spread to regions of the cell that can support but not initiate waves. In atrial cells, an action potential triggers the firing of surface CRUs, which may initiate Ca2+ waves. After its formation, the wave may propagate under less stringent conditions than that required for wave initiation.

DISCUSSION

Ca2+ waves triggered by an action potential serve the normal physiological role of rapidly activating Ca2+ release throughout the atrial myocyte to ensure rapid and robust contraction. On the other hand, spontaneously generated Ca2+ waves in atrial and ventricular myocytes could contribute to generating arrhythmias. This article examines the factors that affect Ca2+ wave initiation in cardiomyocytes.

Our main focus is to understand the effect that the spatial distribution of CRUs has on Ca2+ dynamics. The most important finding is that the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation is exquisitely sensitive to the spatial distribution of the CRUs. This suggests that the contractile state of the myocyte directly influences the dynamics of the Ca2+ control system. This important and novel concept is explored below.

In our effort to understand the physical basis for the sensitivity of Ca2+ dynamics to CRU spatial distribution, we also examined how the CRU Ca2+ current (ISR) and the number of neighboring CRUs that fire synchronously affect the ambient Ca2+ concentration about a CRU. The large effect that these factors—spatial distribution of CRUs, number of CRUs firing, and ISR—have on wave initiation probability all share a common physical basis: saturation of Ca2+ buffers. Intuitively, this is expected since the spread of the Ca2+ wave depends on sufficiently elevating the ambient Ca2+ concentration at the CRU on the wave front. What the analyses and simulations reveal is the surprising magnitude of the nonlinear effect these factors have on the free Ca2+ concentration. We call this nonlinear dependence superadditivity.

In our simulations, the free Ca2+ concentration between the Z-disks during a wave typically reaches ∼15 μM. This value is ∼10 times higher than some estimates of experimentally measured [Ca2+]i (e.g., 4). However, amplitudes of Ca2+ waves vary widely. For example, Kockskämper and Blatter (33) report F/Fo values of 5–13 in cat atrial myocytes using fluo-4. The Ca2+ concentrations corresponding to the F/Fo range of 5–11 are 0.79–12 μM, calculated from the self-ratio formula (34) assuming Kd = 1.1 μM (35) and resting [Ca2+]i of 0.1 μM. Using the data from Lipp et al. (36) and their fluo-3/fura-red calibration curve (37), we calculated the peak averaged [Ca2+]i in a wave to be ∼10 μM.

A wave having a Ca2+ concentration of ∼10 μM is not unexpected given Lukyanenko and Györke's (18) finding that the Ca2+ sensitivity of the CRUs is low, ∼15 μM. If the Ca2+ concentration of a wave were 1 μM, then in 20 ms (the time it takes a wave traveling 100 μm/s to traverse a sarcomere) only ∼8% of the CRUs on a Z-disk would fire. (This calculation uses Eq. 10 and assumes for simplicity that the CRUs see the 1 μM concentration throughout the 20-ms period. Thus, 8% is an upper bound of the fraction of CRUs that fire.) It is unlikely that such a low fraction of firing CRUs could support a wave. However, when a wave has a Ca2+ concentration of 10 μM, 87% of the CRUs fire in that 20-ms period. Ca2+ waves with lower peak Ca2+ can exist when the Ca2+ sensitivity of CRUs is higher, for example, in the presence of low concentrations of caffeine.

Spontaneous Ca2+ spark frequency, ISR, and Ca2+ waves—effects of superadditivity

An increase in the spontaneous Ca2+ spark frequency often precedes the appearance of spontaneous Ca2+ waves (6). Fig. 3 C provides a quantitative explanation for why this occurs. The ordinate is the n-fold increase of the maximum Ca2+ seen by a CRU (the “observer”) 1 μm away from 1, 3, 5, and 7 CRUs that fire. Notice that when three CRUs fire, the observer sees not a threefold increase in Ca2+ concentration but rather a sixfold increase. This disproportionate increase in peak Ca2+ is due to superadditivity of CRU release. The superadditive summation of Ca2+ sparks explains why a small increase in the spark frequency can produce an inordinate increase in the probability of more sparks and, by extension, a large increase in the probability of initiating a Ca2+ wave.

Superadditive effects also underlie the great sensitivity of the Ca2+ concentration to changes in CRU current. Figs. 3 C and 5 B show that the peak Ca2+ concentration increases nonlinearly with ISR. An approximately twofold change of ISR (from 8.4 to 16 pA) produces a 21-fold increase in the peak Ca2+ concentration measured 1 μm away. Thus, even a modest increase in the Ca2+ flux from a spark can greatly increase the probability of Ca2+ waves.

Coupling between contractile dynamics and Ca2+ dynamics: large-scale cooperative CRU interactions

A surprising and important finding of this study is the remarkable sensitivity of the Ca2+ dynamics to the spatial distribution of the CRUs. A small decrease in the distance between CRUs in the plane of the Z-disk (Λ) can result in qualitatively different Ca2+ dynamics (Fig. 2). This sensitivity results from the rapid decline of the Ca2+ concentration as a function of distance from the source, as shown in Figs. 3 B (the 2-D case) and 5 A (the 3-D case). Note that a CRU sees a fourfold (2-D) or 12-fold (3-D) increase in the peak Ca2+ concentration as it moves just 0.2 μm closer, from 1.0 to 0.8 μm, to the Ca2+ source. Since the probability of CRU firing depends on the ambient Ca2+ concentration, a small change in CRU spacing will profoundly affect the firing probability.

Ca2+ dynamics is also sensitive to large-scale cooperative CRU interactions. By this, we mean that the firing probability of a CRU on one Z-disk not only depends on the firing history of other CRUs on that Z-disk, but also on the firing histories of adjoining intercalated CRUs and of CRUs on adjacent Z-disks. The simulations in Fig. 6 illustrate the basic idea of large-scale cooperative CRU interactions. The simulations are identical except that cooperative interactions between CRUs on the two Z-disks are absent in Fig. 6 A but present in Fig. 6 B. In the absence of cooperative interactions the triggered firing of CRUs fails to initiate a Ca2+ wave (Fig. 6 A), but by allowing interaction of CRUs on adjacent Z-disks, the firing activity of CRUs on one Z-disk regeneratively reinforces the firing activity of CRUs on the other Z-disk. This mutual reinforcement results in Ca2+ wave initiation (Fig. 6 B).

Because of large-scale cooperative CRU interactions, the probability of wave initiation is influenced by the distance between Z-disks, that is, the sarcomere length. Fig. 9 B illustrates this point. Fig. 6 A shows that when the Z-disk distance is 2.0 μm a Ca2+ wave fails to initiate. However, when the Z-disk distance is reduced to 1.8 μm (Fig. 6 B) or 1.6 μm (Fig. 6 C), the same conditions allow a Ca2+ wave to form. The physiological implication is that the contractile state of the myocyte affects the dynamics of the Ca2+ control system. This novel feedback pathway arises solely from changes in the spatial distribution of CRUs as a result of contraction. This pathway is distinct from the coupling of contractile system to the Ca2+ control system via an NO-mediated mechanism (38) and also independent of the decrease in Ca2+ binding to troponin-C at shortened sarcomere lengths (39,40).

Physiological implications of large-scale cooperative CRU interactions

Ca2+ waves in atrial cells

Atrial myocytes, unlike ventricular myocytes, lack t-tubules, so Ca2+ release directly triggered by depolarization occurs mainly at the cell periphery (1–4,41,42) and, to a lesser extent, at sparse sites inside the cell (2). If Ca2+ release occurred only from CRUs directly triggered by depolarization, it would activate the myofilaments near the periphery, but myofilaments near the cell core would be only slightly activated and the slow rate of activation would reflect the passive diffusion of Ca2+ (2). On the other hand, centripetally propagating Ca2+ waves would greatly increase the rate and magnitude of myofilament activation at the core (2). For atrial cells to use Ca2+ waves, the Ca2+ control system must be delicately poised in a state of “controlled instability” wherein there is enough regenerative Ca2+ release to support wave propagation but not so much as to generate waves spontaneously.

The spacing of CRUs in the plane of the Z-disk (Λ) is important for determining the state of controlled instability. A small change of Λ from 1.0 to 0.8 μm has a large effect on the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation (Fig. 3). Indeed, in the limit of Λ = 0 we would obtain the common pool model, whose failure to explain the graded Ca2+ release prompted Stern (43) to propose the local control theory of E-C coupling. On the other hand, our model could not produce Ca2+ waves with a transverse spacing of Λ = 2 μm, as reported in cat atria (44). Our results suggest, then, that RyR2 clusters in species other than rat (which our model is based on), and in other cell types (e.g., neurons) where Ca2+ waves are found, would also be spaced ∼1 μm apart. Large departures from this value would indicate that compensatory changes (e.g., ISR, RyR2 sensitivity to Ca2+) need to occur to maintain a state of controlled instability.

Possible function of intercalated CRUs to control wave initiation in atrial cells

A way of modulating the rate and magnitude of contraction in atrial myocytes would be to control the initiation of Ca2+ waves. When the intercalated CRUs are functional, both the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation and Ca2+ wave velocity greatly increase (Figs. 7 and 8). Thus, if there were a way of turning the intercalated CRUs on or off then this would be a means of controlling atrial myocyte contractility.

One possible way of modulating intercalated CRU activity is suggested by the finding that inositol-1,4,5 trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are colocalized with the RyR2s on the sarcolemma but not in the interior of rat atrial cells (45,46). Activation of the IP3Rs results in an increase in the spark frequency in the subsarcolemmal region (45) and extra Ca2+ transients after action potential triggered Ca2+ release (46). A different pattern of IP3R distribution is found in cat atrial cells. In these cells Zima and Blatter (47) observed that IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, similar to Ca2+ puffs (47), occurred throughout the cell.

We want to be clear that at this time we do not know whether the intercalated RyR2s are functional CRUs that release Ca2+ in response to depolarization or whether they release Ca2+ at all. Woo et al. (42) found that Ca2+ sparks on the cell periphery of rat atrial myocytes were spaced between 1.4 and 2 μm apart. This result suggests that, at least under the conditions of their experiments (no IP3R agonists were used), the intercalated CRUs were not functional.

Possible role of contractile Ca2+ system coupling in generating arrhythmias: “Short CRU spacing, more Ca2+ waves” concept

Spontaneous Ca2+ waves can induce sufficiently large depolarization to trigger an action potential (10,11), causing delayed afterdepolarizations (49,50) and possibly cardiac arrhythmias (7,12,51). Known factors that predispose the cell to spontaneously generate Ca2+ waves include increased sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load (6,52–54) and increased RyR2 open probability (55–58). The study presented here suggests an additional important factor: shortened CRU spacing.

Shortened CRU spacing was observed in the ventricular myocytes from the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) at the late-stage cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. In comparison to the controls, the average longitudinal CRU spacing (which corresponds to Z-disk spacing or sarcomere length) in the SHR was 5% shorter in the isolated cells and 10% shorter in the tissue cross section (Y. Chen-Izu, C. W. Balke, and L. T. Izu, unpublished data) in comparison to the age-matched WKY controls. Consonant with the “short CRU spacing, more Ca2+ waves' idea, the hypertrophied SHR hearts had higher incidence of spontaneous Ca2+ waves (59) and higher susceptibility to arrhythmias in vivo (60) and in the isolated heart (61).

Shortened sarcomere spacing was also reported in two transgenic mouse models of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC). One model with the troponin T (R92Q) mutation displayed 10% shortening of the sarcomere length in the ventricular myocytes (62). Another model with mutations in the actin-binding domain of α-myosin heavy chain displayed 5% shortening of the sarcomere length (63). Humans with the same mutations suffer high risk of sudden cardiac death (64,65)

The above data from SHR and FHC models support the plausibility of the “short CRU spacing, more Ca2+ waves” concept. However, it should be noted that these measurements were done in unloaded cells and in tissue sections from unloaded hearts. It is unknown whether the degree of shortening seen in the unloaded cells and tissues is also present in the working myocardium. Thus, care must be taken in extrapolating the expected increase in spontaneous Ca2+ waves due to sarcomere shortening seen in unloaded cells and tissues to the working heart.

In both the SHR and the two FHC mutants described, the sarcomeres were shortened and the SR Ca2+ load was normal or even elevated compared to controls (63,66). This combination acts in synergy to increase the likelihood of spontaneous Ca2+ waves. By contrast, in human heart failure (HF) (67), in the dog (68,69), and in a rabbit model (8) of pressure-overload-induced HF, the SR Ca2+ load was reduced. Moreover, the mean sarcomere spacing remained the same in isolated myocytes from failing and nonfailing human left ventricle (70) and in isolated right ventricular myocytes from hypertrophied and normal rabbits (71). Thus, in human and rabbit HF, the combination of reduced SR Ca2+ load and normal sarcomere lengths would reduce the probability of spontaneous Ca2+ waves (assuming sarcomere lengths remain the same as the rabbit heart progresses from hypertrophy to HF). This conclusion, however, should be tempered, because it does not take into consideration the distribution of sarcomere lengths. In the human HF, the distribution of mean sarcomere lengths from normal hearts is Gaussian, but from hypertrophied hearts it is significantly left-skewed (71), meaning that there is a higher preponderance of cells from hypertrophied hearts than expected with short sarcomere lengths. This preponderance might be important, because spontaneous Ca2+ waves could be started in these cells with shortened sarcomeres and become foci for initiating Ca2+ waves. Fig. 9 C shows the relationship between sarcomere spacing and CRU current that determines whether the likelihood of spontaneous Ca2+ waves is high (unstable) or low (stable). Suppose point a is the initial state of the myocyte; the sarcomere length is 2 μm and ISR ≈ 20 pA. Since this state is below the curve, the likelihood of spontaneously generated Ca2+ waves is low. If the sarcomere length is reduced to 1.8 μm and the current is unchanged, then, as point b is above the curve, the system loses stability and there is a high probability that Ca2+ waves emerge spontaneously.

Limitations of the model and future developments

The model uses a number of simplifications dictated by a need to keep the computational burden within reason and the unavailability of experimental data to warrant a more detailed model. The steady-state response of the RyR2 opening probability to Ca2+ was used (Eq. 3), which allows us to analytically compute the WTD for CRU firing based on a canonical distribution of Ca2+ (a pulse or wave), enables us to rapidly obtain the archetypal behavior of this stochastic system. Without this simplification the mean behavior of the system would need to be found by averaging the results of many simulations. However, the use of steady-state behavior is likely to be inadequate when simulating the response of the CRUs to the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels, as the RyR2 opening probability is higher when Ca2+ changes rapidly than under steady-state conditions (72,73).

We have proposed a novel explanation of the heightened risk of arrhythmias in some forms of HF based on our finding of the strong coupling between the contractile and Ca2+ control systems in tandem with the finding that the sarcomere length is significantly shortened in the SHR and two FHC mutants (62,63). This explanation, however, is based on a static view of the sarcomeres. The cooperative interactions between CRUs on adjacent sarcomeres still operate during a heartbeat, but the magnitude of the cooperativity will depend also on the changing SR Ca2+ load and changing sarcomere distance. The current model does not include the dynamics of the lumenal SR Ca2+. We have explored how the interplay of a reduced SR Ca2+ load and sarcomere shortening affect wave initiation (Fig. 9 C), but a dynamic description of the SR Ca2+ content is needed to fully understand the interaction between the contractile and Ca2+ control systems. New developments in dynamic measurement of lumenal Ca2+ content (74–76) will provide information about how SR load affects Ca2+ release and the next generation of our model will incorporate these new insights.

SUMMARY

Simulations and analytic results presented here show that the probability of Ca2+ wave initiation is extremely sensitive to even small changes in RyR2 distribution, CRU current, and Ca2+ spark frequency. This insight suggests that there is a strong, hitherto underappreciated, coupling between the contractile system—which dynamically modulates the RyR2 distribution—and the Ca2+ control system. Cardiac arrhythmias have a complex etiology and we propose that the coupling between the RyR2 distribution and the Ca2+ control system may contribute, in part, to the generation of cardiac arrhythmias.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants K25HL068704 (L.T.I.), RO1HL68733 (C.W.B.), RO1HL50435-05 (C.W.B.), RO1HL071865 (C.W.B. and L.T.I.), Veterans Administration Merit Review Award (C.W.B. and L.T.I.), National Center for Supercomputing Applications MCB00006N (L.T.I. and C.W.B.), and American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 0335250N (Y.C.). This work was partially funded by the Department of Energy Office of Science Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences Division program at Sandia National Laboratory. Sandia is a multi-program laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-AC04-94AL85000.

APPENDIX A

The model equations are nearly identical to those used previously (15,16) except that for most simulations they were extended to three dimensions; the results shown in Figs. 3 and 10 are from 2-D simulations. The coordinate axes for the 3-D simulations are shown in Fig. 1. The Z-disk lies in the xy plane and the long axis of the cell is along the z axis. The partial differential equation (PDE) for Ca2+ is given by Kirk et al. (2). The PDEs for the free endogenous (FB) and exogenous (FD) buffers are

|

(A1) |

|

(A2) |

where (j = D or B)

|

(A3) |

and Hj is the total (free + Ca2+-bound) buffer concentration. The standard parameter values for these buffer reactions are given in Table 1 of our previous work (15), which also gives the sources for these values. For convenience, these parameters are listed here: HB = 123 μM; these values are lumped parameters for endogenous Ca2+ buffers (77). To reduce the computational load, the model did not differentiate between different endogenous buffers such as troponin-C and calmodulin. Other parameters are DCx = DCy = 0.15 μm2/ms, DCz = 0.30 μm2/ms, DDx = DDy = 0.01 μm2/ms, DDz = 0.02 μm2/ms;  = 100/μM/s,

= 100/μM/s,  = 100/s;

= 100/s;  = 80/μM/s,

= 80/μM/s,  = 90/s (78). The initial Ca2+ concentration is C(0,x,y,z) = 0.1 μM (except for the simulation in Fig. 10). The parameters describing the probability of opening of the CRUs given in Eqs. 2 and 3 have the following standard values: Topen = 5 ms, Pmax = 0.3/ms, K = 15 μM, and n = 1.6 (see Izu et al. (16) and references therein). The parameters for the SERCA2 pump,

= 90/s (78). The initial Ca2+ concentration is C(0,x,y,z) = 0.1 μM (except for the simulation in Fig. 10). The parameters describing the probability of opening of the CRUs given in Eqs. 2 and 3 have the following standard values: Topen = 5 ms, Pmax = 0.3/ms, K = 15 μM, and n = 1.6 (see Izu et al. (16) and references therein). The parameters for the SERCA2 pump,

|

(A4) |

are Vp = 200 μM/s, Kp = 0.184 μM, and np = 4. Jleak is adjusted such that Jpump − Jleak = 0 when C = 0.1 μM.

APPENDIX B

The idea of superadditivity captures the effect that multiple CRUs or increasing CRU current have on the Ca2+ concentration at an observation point. If the firing of a CRU raises the Ca2+ concentration at the observation point by ΔC(1), what would the concentration change (ΔC(2)) be if another CRU fires? We chose the term superadditivity because buffer systems share the defining property of superadditive functions: f(x + y) ≥ f(x) + f(y) for all x and y. For example, x and y could be the amount of Ca2+ released by two CRUs and the concentrations change at an observation point because the combined effect, f(x + y), is greater than the linear combination, f(x) + f(y), of each CRU by itself. To sensibly compare the changes that occur in buffered and unbuffered systems we consider the changes in concentration relative to some reference state instead of the absolute changes. That is, we are interested in ΔC(2)/ΔC(1). In the special case where the chemical reactions are in equilibrium, the superadditivity effect is readily calculated. Consider the following bimolecular reaction occurring in a volume V:

|