Abstract

Mutations within the structural gene of ampD can lead to AmpC overproduction and increases in β-lactam MICs in organisms with an inducible ampC. However, identification of mutations alone cannot predict the impact that those mutations have on AmpD function. Therefore, a model system was designed to determine the effect of ampD mutations on ceftazidime MICs using an AmpD− mutant Escherichia coli strain which produced an inducible plasmid-encoded AmpC. ampD genes were amplified by PCR from strains of E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Also, carboxy-terminal truncations of C. freundii ampD genes were constructed representing deletions of 10, 21, or 25 codons. Amplified ampD products were cloned into pACYC184 containing inducible blaACT-1-ampR. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli strains JRG582 (AmpD−) and K-12 259 (AmpD+). The strains were evaluated for a derepressed phenotype using ceftazidime MICs. Some mutated ampD genes, including the ampD gene of a derepressed C. freundii isolate, resulted in substantial decreases in ceftazidime MICs (from >256 μg/ml to 12 to 24 μg/ml) for the AmpD− strain, indicating no role for these mutations in derepressed phenotypes. However, ampD truncation products and ampD from a partially derepressed P. aeruginosa strain resulted in ceftazidime MICs of >256 μg/ml, indicating a role for these gene modifications in derepressed phenotypes. The use of this model system indicated that alternative mechanisms were involved in the derepressed phenotype observed in strains of C. freundii and P. aeruginosa. The alternative mechanism involved in the derepressed phenotype of the C. freundii isolate was downregulation of ampD transcription.

The overproduction of AmpC β-lactamase by gram-negative organisms results in resistance to most β-lactam antibiotics with the exception of cefepime, cefpirome, and the carbapenems (40). The regulation of ampC gene expression can differ between genera of gram-negative organisms. For example, the production of the AmpC β-lactamase in Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter freundii, Serratia marcescens, Morganella morganii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is inducible, and the gene is encoded on the chromosome (4, 12, 13, 17, 33). However, gene expression of the chromosomally encoded AmpC of Escherichia coli is regulated by promoter and attenuator mechanisms and is not inducible (13). Furthermore, ampC genes from different genetic origins including C. freundii and M. morganii have been found on plasmids (2, 40). The movement of these genes onto plasmids increased the prevalence of this resistance mechanism by dissemination of the gene into gram-negative organisms which normally do not carry genes encoding AmpC, such as Salmonella spp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae (2, 3). These plasmid-mediated genes have also been found in E. coli (31). Of the more than 20 plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases, five are inducible including DHA-1, DHA-2, ACT-1, CMY-13, and CFE-1 (2, 5, 9, 27, 28).

The induction of AmpC β-lactamase is controlled by the activity of three proteins: AmpG, AmpD, and AmpR. AmpG is a cytoplasmic membrane-bound permease which allows entry of cell wall degradation products. These products, 1,6-anhydromuropeptides, are cleaved by AmpD, an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase, into 1,6-anhydromuramic acid and peptide (16, 42). The peptide is processed into tripeptide, which is reused by the enzymes of the cell wall recycling pathway, ultimately resulting in the formation of the cell wall precursor, UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide. AmpR is a transcriptional regulator of ampC expression, and binding of 1,6-anhydromuropeptide to AmpR results in induction of ampC gene expression (15). Conversely, when AmpR is bound by the cell wall precursor, UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide, ampC is repressed.

In a wild-type (WT) cell, AmpC production is expressed at constitutively low levels due to the binding of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide to AmpR. Mutations associated with AmpR and AmpD can result in AmpC overproduction, which has been termed derepression (1, 12, 19, 22, 25, 39). Phenotypically, derepressed mutants can be resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, which is attributed to the overproduction of AmpC (37). The mechanism most associated with constitutive overproduction of AmpC (full derepression) is amino acid substitutions within AmpD (12, 39). It has been suggested that these mutations interfere with the ability of AmpD to cleave the substrate (1,6-anhydromuropeptide), leading to an increase in the cytoplasmic pool of 1,6-anhydromuropeptide compared to UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide, resulting in AmpC overproduction (39). In addition to the role of AmpD in AmpC production, it is an important enzyme in the cell wall recycling pathway (16). Therefore, ampD genes are found in many gram-negative organisms including K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Salmonella spp (8, 36, 41). Furthermore, these organisms do not normally carry an inducible ampC gene and mutations within the ampD structural gene which could contribute to a derepressed phenoytpe would not be detected phenotypically. However, when E. coli and K. pneumoniae contain an inducible plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, mutations within the structural gene of ampD could lead to increased ampC expression from the imported gene, resulting in increased oxyiminocephalosporin MICs (36).

AmpD mutations associated with derepression include point mutations, truncations, and large insertions, primarily disrupting the carboxy terminus of the protein (1, 7, 19, 22, 25, 39). The AmpD protein has two important binding sites: a zinc-binding pocket and a substrate (1,6-anhydromuropeptide) binding site. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structural analysis of the Citrobacter freundii AmpD has identified key amino acids required for AmpD function (11). The amino acids required for zinc binding include an aspartic acid at position 164 and two histidines at positions 34 and 154. Amino acids important for binding substrate are hydrophobic in nature and are concentrated in the amino terminus of the protein. These findings support previous research by Stapleton et al. that mapped point mutations associated with derepression to the aspartic acid residue at position 164 and a valine residue at position 33 (39).

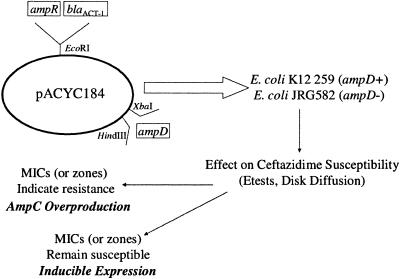

Sequence analysis of ampD genes obtained from phenotypically derepressed mutants can identify potential mutations which may affect AmpC production. However, identification of sequence variation alone is not enough to determine the effect that those mutations elicit on AmpC production. Therefore, a model system was developed to identify the role of nucleotide variations identified in different gram-negative organisms in the overproduction of AmpC and resistance to the oxyiminocephalosporin ceftazidime (CAZ). In this model, an inducible ampC β-lactamase, blaACT-1, was used as the indicator for a susceptible or resistant ceftazidime phenotype. The inducible ACT-1 system (blaACT-1 and ampR) was cloned into a modified pACYC184 vector in which ampD test genes can also be cloned, negating the use of two different vector systems. The ampD test genes have nucleotide variations which result in amino acid substitutions. To test the significance of these nucleotide/amino acid variations, the plasmid containing all three genes is cloned into two E. coli hosts that differ with respect to the ampD gene (i.e., wild type or mutant). If the substitutions identified in the ampD sequence do not inhibit the functionality of the ampD gene product, the plasmid cloned into the ampD mutant host will complement the host gene, resulting in a ceftazidime-susceptible phenotype. If the test gene does not complement the ampD mutant phenotype, the resulting ceftazidime phenotype will be resistant. The flexibility of the test was demonstrated by three susceptibility testing methods: agar dilution, Etest, and disk diffusion. The use of this model system suggested that mechanisms other than mutations within the structural gene of AmpD can be responsible for derepressed phenotypes observed in clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used in this study.

Two E. coli strains were used for the cloning experiments: JRG582, an ampD-negative mutant (ΔnadC-aroP) (23), and an ampD+ strain, K-12 259 (GenBank accession number D90770). ampD genes were isolated and tested from E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, and P. aeruginosa. A laboratory strain of E. coli (HB101) was the source of a wild-type ampD gene, and an E. coli isolate from a urinary tract infection, CUMC5 (with AmpD amino acid substitutions Val9Ala, Cys143Arg, Lys149Asn, Val176Ala, and Val178Ile), served as the source of mutated ampD. The C. freundii ampD sources were C. freundii strains CF21 (a clinical isolate with a wild-type β-lactam susceptibility pattern) and its single-step mutant selected with cefotaxime, CF21M (derepressed phenotype) (14). Finally, three strains of P. aeruginosa were used as source organisms for ampD: PAO1, a laboratory control strain; Ps164, a clinical isolate with a wild-type β-lactam susceptibility pattern (34); and Ps164 M1, a single-step mutant selected from Ps164 using cefotaxime which was phenotypically characterized as partially derepressed for AmpC production (10).

Template preparation.

Template DNA for PCR was prepared from overnight cultures of E. coli and C. freundii and an 8-hour culture of P. aeruginosa using 1.5 ml of culture as previously described (32). A final concentration of 400 μg/ml of proteinase K was added to P. aeruginosa supernatant prior to lysis to protect the nucleic acid from nuclease degradation.

PCR of test strains.

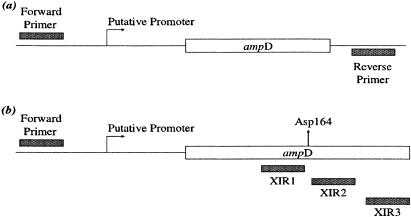

ampD genes were amplified by PCR as previously described (35) using the proofreading enzymes High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) for E. coli and C. freundii and Precision Taq polymerase (Stratagene) for P. aeruginosa. The DNA template was generated from strains described above. Primers used for amplification are listed in Table 1. The corresponding binding sites of the primers are depicted in Fig. 1. The amplified product contained the putative promoter region, translational start codon, and structural ampD gene. Each forward primer (Table 1) binds 316, 136, and 223 bp upstream of the start codon for E. coli, C. freundii, and P. aeruginosa (respectively) to include the putative promoter for ampD. Three internal reverse primers (Table 1) specific to C. freundii ampD were used to truncate the gene at codons 160, 165, and 175 and contained a stop codon in frame with the AmpD protein sequence. Amplified ampD genes were separated and visualized using a 1.0% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer namea | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purposeb | Nucleotidesc | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli ampD | ||||

| ampDUF | CTCTTCAACCCAGCGTTTGC | A | 118418-118437 | NC_000913 |

| ampDAKR | GCACTGGCAGCTTGATCATCG | A | 119360-119340 | NC_000913 |

| C. freundii ampD | ||||

| CFampDF | CCAGAAGCGCGTCACGTCGG | A | 18-37 | Z14002 |

| CFampDR | TCATGTCATCTCCTTGTGTGACG | A | 717-695 | Z14002 |

| XIR1d | CTACTCGGGCCGCAATATTGC | A | 635-617 | Z14002 |

| XIR2 | CTAGGGATCGGTCTTACGCTCG | A | 648-630 | Z14002 |

| XIR3 | CTAGCTAAACCTTGCCCAAGTC | A | 680-661 | Z14002 |

| P. aeruginosa ampD | ||||

| PAampDF | GACGATGCCTTGCTGTTCG | A | 436-454 | AF082575 |

| PAampDR | GCAGCAATGTCAGCAACAGG | A | 1422-1403 | AF082575 |

| C. freundii | ||||

| CFRRNAFe | GTTGTGGTTAATAACCGCAGCG | R | 436-457 | AJ233408 |

| CFRRNAR | GCTTTACGCCCAGTAATTCCG | R | 556-536 | AJ233408 |

| CFampCF | CGAAGCCTATGGCGTGAAATC | R | 1772-1792 | AY125469 |

| CFampCR | CCAATACGCCAGTAGCGAG | R | 1906-1888 | AY125469 |

| CFampDF | GCATGTTGTTAGACGAGGG | R | 152-170 | Z14002 |

| CFampDR | CGGCAGGCTGATATTATGC | R | 270-252 | Z14002 |

Primer names ending with F represent forward primers; those ending with R represent reverse primers.

Purpose for the primers: A, amplification, cloning, and sequencing; R, real-time RT-PCR.

Nucleotide location of each primer with respect to the GenBank accession number cited, listed 5′-3′.

XIR1, XIR2, and XIR3 primers bind internal to the ampD gene and contain an in-frame stop codon.

Primers used to amplify 16S rRNA from C. freundii as an endogenous control for real-time RT-PCR experiments.

FIG. 1.

Primer binding sites for ampD amplification and cloning. (a) Specific forward and reverse primers (Table 1) were used to amplify the structural gene, putative promoter, and upstream region of ampD test genes used for the generation of clones with ampD inserts derived from E. coli strains HB101 and CUMC5; C. freundii strains CF21 and CF21M; and P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, Ps164, and M1. (b) Locations and names of primers used to generate truncated PCR-amplified products of the CF21 ampD gene. The PCR was performed using the forward primer CFampDF and XIR1, XIR2, or XIR3, which resulted in truncated products with a loss of 25, 21, or 10 codons from the carboxy terminus, respectively.

Cloning.

The amplified ampD genes were extracted from the agarose gel using a SNAP column (Invitrogen), ligated into pCR-TOPO-XL (Invitrogen), and transformed into Top 10 E. coli cells (Invitrogen). The ampD fragment was subcloned, using the restriction enzymes XbaI and HindIII, into pACYC184 containing blaACT-1-ampR (Fig. 2) (36). The resulting plasmid was electroporated into E. coli JRG582 (ΔnadC-aroP) (ampD mutant) (23) and K-12 259 (WT ampD) as described by Hossain et al. (14).

FIG. 2.

Development of the ampD model system. An inducible ampC β-lactamase, blaACT-1, is used as the indicator for a susceptible or resistant ceftazidime phenotype. The ampD gene to be tested was amplified by PCR and cloned into a moderate-copy-number (12 copies) plasmid, pACYC184, containing the ampC β-lactamase gene and its transcriptional regulator gene, ampR (35). The amplified ampD product contained the entire structural gene as well as upstream sequence to allow gene expression from its native promoter. The plasmid was transformed into two different E. coli backgrounds, an ampD mutant strain (JRG582) (23) and a WT ampD+ strain (K-12 259). Both of these strains are E. coli K-12 derivatives. Following transformation, the ceftazidime MICs were determined. If the test ampD gene represented a mutant which results in overproduction of AmpC, the ceftazidime MICs in JRG582 clones were very high (>256 μg/ml), representing a failure to complement the ampD mutant background of JRG582, but if the test ampD gene represented a wild-type gene which would not influence AmpC overproduction, ceftazidime MICs were low (≤12 μg/ml) for the JRG582 clones, representing a susceptible phenotype. Wild-type AmpD represents a dominant phenotype, so no change in the resistant phenotype was observed when test ampD genes were transformed into the AmpD WT strain (K-12 259).

Ceftazadime susceptibility assays.

The susceptibility of ampD clones to ceftazidime was determined by Etest (AB Biodisk, Sweden) and disk diffusion (30 μg) using the manufacturer's instructions and CLSI (formerly NCCLS) criteria (29). The agar dilution methodology assay was performed according to CLSI guidelines to identify the ceftazidime MICs for clones with Etest ceftazidime MICs of >256 μg/ml (30).

Sequencing.

Plasmids containing the ampD insert were purified for sequencing using a Microcon YM-10 filter column (Millipore Corporation), and PCR-amplified products, including the ampC and ampR genes of C. freundii, were purified using YM-50 filter columns (Millipore Corporation). Sequencing was performed by automated cycle sequencing using an ABI Prism 3100-Avant Genetic analyzer using primers listed in Table 1.

BLAST analysis.

Mutations and amino acid changes were analyzed by comparing them to wild-type sequence of their respective genera using the BLAST program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). E. coli ampD genes were compared to the E. coli strain K-12 sequence (accession number NC_000913), ampD sequences of C. freundii were compared to C. freundii strain OS 60 (accession number Z14002), and ampD genes from P. aeruginosa were compared to the P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (accession number AF082575). Additionally, the ampC and ampR genes from C. freundii CF21M were compared to strain CF21 (accession number AY125469).

RNA isolation.

Overnight cultures (5 ml) of CF21 and CF21M were diluted 1:20 (100-ml total volume) in Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid) and allowed to grow to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 at 37°C with shaking at 125 rpm. Cells were centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of modified Trizol-Max (Invitrogen) solution (36). Protein was removed by treatment with a phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol solution (25:24:1), and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol. To eliminate DNA contamination, 8 μg of isolated RNA was treated for 1 hour with 8 units of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions; however, the 65°C heat inactivation step was omitted to prevent shearing of the RNA.

Real-time RT-PCR.

DNase-treated RNA isolated from CF21 and CF21M was examined using real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (43). Each reaction mixture was comprised of 25 μl 2× QuantiTect SYBR green RT-PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN), 0.5 μM of the forward primer and 0.5 μM of the reverse primer (Table 1 lists primers used), 0.5 μl QuantiTect RT Mix (QIAGEN), and 150 ng of DNase-treated RNA. RNase-free water was added for a total volume of 50 μl. An ABI 7000 sequence detection system was programmed for the following parameters: an initial 40-min 50°C reverse transcription step and a 15-min 95°C denaturation and activation step. Next, 40 cycles of PCR were performed: 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Data were evaluated using ABI Prism 7000 SDS software with an amplification threshold of 0.4. All RNA samples were evaluated for the presence of DNA template using a reaction mixture for each sample in the absence of reverse transcriptase but in the presence of DNA polymerase. Only samples indicating the absence of DNA were used for analysis. Expression of 16S rRNA was used to normalize the relative expression data for ampC and ampD. The experiment was performed three times, and the final relative expression of ampC and ampD was determined by averaging the results for the respective transcripts. First the cycle thresholds (CT) for each gene were averaged between the three experiments (standard deviation, ≤0.672) and the relative expression was calculated using RQ =  (26). Using these parameters, the coefficient of variation for all data used was ≤10%.

(26). Using these parameters, the coefficient of variation for all data used was ≤10%.

RESULTS

Susceptibility and phenotypes of ampD clones.

The ceftazidime MICs and zones of inhibition for ampD clones in ampD+ (K-12 259) and ampD mutant (JRG582) genetic backgrounds are listed in Table 2. Disk diffusion was used to evaluate susceptibility for two reasons: (i) this methodology provided an inexpensive alternative to MIC methodologies in establishing a susceptibility phenotype and (ii) these results were used to further evaluate Etest MIC data, especially when an intermediate result was obtained. The recipient strains (JRG582 and K-12 259) with and without the plasmid pACYC184 containing blaACT-1-ampR were used as controls. When the recipient strains were tested in the absence of plasmid, ceftazidime MICs were 0.064 μg/ml for JRG852 (zone size, 32 mm) and 0.25 μg/ml for K-12 259 (zone size, 30 mm). Transformation with pACYC184 containing blaACT-1-ampR into JRG582 and K-12 259 raised the ceftazidime MICs to >256 and 12 μg/ml (zones, 6 and 19 mm, respectively), respectively. These data supported the hypothesis that the absence of AmpD (JRG582) correlated with overexpression of ampC (blaACT-1) and a derepressed phenotype as previously described (35).

TABLE 2.

MICs for ampD clones in WT and ampD mutant E. coli background

| Plasmid or origin of ampD insert | ampD insert characteristic(s) | K-12 259a,k

|

JRG582b,k

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ MICc (μg/ml) | Zone diamd (mm) | CAZ MICc (μg/ml) | Zone diamd (mm) | ||

| Plasmids | |||||

| None | No ampD insert | 0.25 (S) | 30 (S) | 0.064 (S) | 32 (S) |

| ACYC184 (ampR blaACT-1) | No ampD insert | 12 (S) | 19 (S) | >256 (R) | 6 (R) |

| Origin of ampD insert | |||||

| E. coli | |||||

| HB101e | WT | 16 (I) | 19 (S) | 24 (I) | 18 (S) |

| CUMC5f | V9A, C143R, K149N, 176A, V178I | 16 (I) | 19 (S) | 12 (S) | 19 (S) |

| C. freundii | |||||

| CF21g | R175S | 16 (I) | 19 (S) | 4 (S) | 19 (S) |

| CF21Mh | R175S | 24 (I) | 19 (S) | 12 (S) | 19 (S) |

| CF21-XIR1 | TAG at E160 | 24 (I) | 17 (I) | >256 (R) | 6 (R) |

| CF21-XIR2 | TAG at P165 | 24 (I) | 18 (S) | >256 (R) | 6 (R) |

| CF21-XIR3 | TAG at R175S | 16 (I) | 19 (S) | >256 (R) | 8 (R) |

| P. aeruginosa | |||||

| PAO1 | WT | 16 (I) | 19 (S) | 24 (I) | 18 (S) |

| Ps164i | WT | 24 (I) | 19 (S) | 32 (R) | 16 (I) |

| Ps164 M1j | TAG at Q155 | 16 (I) | 16 (I) | >256 (R) | 6 (R) |

E. coli strain K-12 259: WT ampD.

JRG582: E. coli strain K-12 derivative lacking the ampD gene(23).

Ceftazidime MICs were determined using Etest strips, and susceptibility breakpoints reflect those indicated by CLSI guidelines (29).

Disk diffusion tests for ceftazidime, 30 μg.

E. coli strain HB101 is a laboratory control strain with wild-type β-lactam susceptibility patterns.

E. coli strain CUMC5 is a urine isolate.

C. freundii strain CF21 is a clinical isolate which has an inducible chromosomal ampC (38).

C. freundii strain CF21M is a derepressed (noninducible) mutant derived from CF21 (38).

P. aeruginosa strain Ps164 is a clinical isolate susceptible to all β-lactam drugs (10).

P. aeruginosa strain Ps164 M1 is a partially derepressed mutant selected from Ps164 using cefotaxime (10).

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

To test the association between specific ampD mutations and a derepressed phenotype, ampD genes from E. coli, C. freundii, and P. aeruginosa were cloned into pACYC184 containing blaACT-1-ampR and analyzed for the ability of the cloned ampD to complement the JRG582 phenotype as indicated by a reduction of ceftazidime MICs (Table 2; Fig. 2). If the test ampD gene represented a mutant which resulted in overproduction of AmpC, the ceftazidime phenotype was resistant for JRG582 clones (by both MIC and zone diameter), representing a failure to complement the ampD mutant background of JRG582, but if the test ampD gene represented a wild-type gene which would not influence AmpC overproduction, the ceftazidime phenotype was susceptible (both by MICs and by zone diameter) for the JRG582 clones. Wild-type AmpD represented a dominant phenotype, so no change in the susceptibility phenotype was observed when test ampD genes were transformed into the AmpD wild-type strain (K-12 259).

Sequence analysis of E. coli ampD and the effects of ampD mutations on ceftazidime MICs.

A derepressed phenotype is not normally associated with strains of E. coli because the chromosomal ampC gene is not inducible. However, when E. coli harbors an inducible plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, it could be considered a derepressed mutant with concomitant increases in β-lactam MICs if AmpD was functionally inactive. To determine if ampD mutations were present in clinical isolates of E. coli, 31 E. coli strains isolated from patients with urinary tract infections were examined by sequencing PCR-generated products of ampD and comparing those sequences to the wild-type ampD sequence in E. coli K-12 (accession number NC_000913). Seventy-seven percent (24/31) of the isolates contained mutations within ampD which resulted in amino acid substitutions. Five common mutations were observed (Val9Ala, Cys143Arg, Lys149Asn, Val176Ala, and Val178Ile), and the clinical E. coli isolates could be grouped as having three (12/24), four (5/24), or all five (7/24) of these mutations. The amino acid substitutions were primarily located in the carboxy terminus with the exception of 13 isolates which also had Val9Ala in the amino terminus. One of the isolates, CUMC5, which contained all five common mutations, was selected for evaluation in the ampD model system. E. coli HB101 is a wild-type laboratory strain which carries a wild-type ampD gene and therefore was used as a control. Transformation of JRG582 with the ampD gene of HB101 inserted into the test plasmid resulted in a ceftazidime MIC of 24 μg/ml (zone, 18 mm), and the ampD obtained from CUMC5 resulted in a MIC of 12 μg/ml (zone, 19 mm) (Table 2). These data indicated that the amino acid substitutions observed in the CUMC5 ampD gene did not influence the production of the indicator, ACT-1.

Comparison of the ampD genes between C. freundii ampC wild-type and derepressed isolates.

Two native C. freundii ampD genes from strains C. freundii 21 (CF21) and C. freundii 21 M (CF21M) were tested in the model. CF21M was a single-step mutant selected from CF21 using cefotaxime and has a cefotaxime MIC of 32 μg/ml compared to 1 μg/ml for the parent, CF21. CF21M is phenotypically derepressed and produces >200 times the amount of ampC RNA produced by CF21, which exhibits inducible, wild-type ampC production (14). When tested using the ampD model system, ceftazidime MICs for JRG582 clones containing the ampD genes of CF21 and CF21M were 4 and 12 μg/ml (zones of 19 mm each), respectively. These results were surprising given the derepressed phenotype of CF21M. Sequence analyses of the ampD genes from both CF21 and CF21M indicated a mutation resulting in an amino acid substitution at position R175S in both strains. Taken together, these data indicated that the observed mutation did not result in the derepressed phenotype observed for CF21M.

The ampD gene cloned from the derepressed mutant, CF21M, did not yield a derepressed phenotype in the model. Therefore, to substantiate the idea that an AmpD-mediated derepressed phenotype could be detected using the ampD model system, three PCR-generated mutant ampD genes were constructed from C. freundii strain CF21. Different internal reverse primers were used (Table 1) and resulted in the loss of 25 (primer XIR1), 21 (XIR2), or 10 (XIR3) codons from the carboxy terminus, respectively. These primers contained stop codons in frame with the amino acid sequence. Clones expressing these constructed ampD genes yielded ceftazidime MICs of >256 μg/ml in JRG582 (zones, 6 to 8 mm) and ranged from 16 to 32 μg/ml in K-12 259 (zones, 17 to 20 mm) (Table 2). Strains that exhibited a ceftazidime MIC of >256 μg/ml using Etest were evaluated by agar dilution methodology and found to have a ceftazidime MIC of 128 μg/ml.

Evaluation of ampD gene expression in C. freundii 21 M (CF21M).

The truncated ampD genes verified that the ampD model could be used to detect ampD mutations which resulted in a derepressed phenotype. Together with the sequence analysis of the CF21M ampD gene, these data confirmed that the amino acid substitution within AmpD of CF21M was not the mechanism responsible for the derepressed phenotype. The ampR gene and ampC-ampR intergenic region of CF21M were sequenced and evaluated as alternative mechanisms of derepression in this isolate. No mutations were found in these regions compared to the prototype C. freundii OS60 (GenBank accession number Z14002). Therefore, ampD and ampC expression in the clinical isolate CF21 and its mutant CF21M was analyzed using real-time RT-PCR. CF21M exhibited a 403-fold increase (CT standard deviation, 0.6) in ampC expression and a corresponding 11-fold decrease (CT standard deviation, 0.66) in ampD expression compared to CF21.

Evaluation of the ampD genes in P. aeruginosa.

The plasmid model was further evaluated to determine if ampD genes could be tested from an organism other than those grouped as Enterobacteriaceae (i.e., P. aeruginosa). PAO1 is the prototype strain for P. aeruginosa and was used as a control strain for evaluating P. aeruginosa mutants. When the WT ampD gene from PAO1 was cloned into the plasmid model, the ceftazidime MIC was intermediate (24 μg/ml) but there was a susceptible zone diameter of 18 mm. However, when the ampD gene from a ceftazidime-susceptible clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa, Ps164, was cloned into the model, an intermediate-to-resistant phenotype was observed with ceftazidime MICs of 32 μg/ml in JRG582 (intermediate zone size, 16 mm). Insertion of ampD from Ps164 M1 resulted in a MIC of >256 μg/ml in JRG582 (zone size, 6 mm). Agar dilution methodology indicated that the ceftazidime MIC of the clone expressing ampD of Ps164 M1 in JRG582 was 128 μg/ml. Sequence analysis of the ampD genes of the strains tested indicated a wild-type sequence for Ps164 but a truncation of AmpD at amino acid position 155 for Ps164 M1 (D. J. Wolter, N. D. Hanson, and P. D. Lister, Abstr. 44th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C1-955, 2004).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to develop a model system to evaluate the effect of sequence variation within ampD genes from different genera on AmpC overproduction. Using this model system, alternative mechanisms other than amino acid substitutions were shown to contribute to AmpC derepression. There are several advantages to examining ampD sequence variation in this model system. First, the genes corresponding to the inducible β-lactamase phenotype, blaACT-1-ampR, were cloned into the same plasmid as the ampD insert, negating any copy number effect between the genes expressing the β-lactamase and AmpD and eliminating any potential plasmid compatibility issues. Second, JRG582 and K-12 259 are both K-12 E. coli derivatives providing a controlled genetic background. Third, the initial effects of ampD mutations can be determined inexpensively using disk diffusion compared to more expensive or labor-intensive methods such as Etest or agar dilution methodology. Finally ampD genes from different genera can be evaluated for their effects on ampC expression in one model system.

A wild-type AmpD encoded by the model system was identified based on decreased ceftazidime MICs (from >256 μg/ml to ≤24 μg/ml) or increases in zone size for ampD clones in the ampD mutant background (JRG582) with no substantial difference in the K-12 259 background (Table 2). The decrease in ceftazidime MICs indicated a lower constitutive level of blaACT-1 expression due to complementation of the ampD mutant E. coli strain JRG582 by the test ampD gene in the plasmid. The variation observed for the K-12 259 clones most likely represents fluctuations in Etest results as the zone sizes for all clones indicated a susceptible, or in one case an intermediate, phenotype. Insertion of E. coli and C. freundii native ampD genes as well as the wild-type genes of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and Ps164 resulted in decreased ceftazidime MICs in the AmpD− E. coli strain JRG582 (Table 2). These ceftazidime MICs indicated that ampD sequence variations observed for CUMC5 and CF21 and CF21M were associated with a wild-type phenotype. Mutations within AmpD responsible for a derepressed phenotype were identified using the ampD model system based on the inability of the test genes to complement the ampD mutant phenotype of JRG582 as observed for the CF21 ampD truncated clones and strain Ps164 M1 (CAZ MICs remained >256 μg/ml [Table 2]).

Although the ampD gene product of E. coli strain CUMC5 had five amino acid substitutions, the gene encoding that product was capable of complementing an ampD mutant phenotype. It is possible that amino acid substitutions that fall outside the highly conserved regions of AmpD do not substantially contribute to the overall function of the enzyme. If these amino acid substitutions contribute to minor changes in the AmpD enzymatic activity, the model system may not be able to differentiate those contributions for at least two reasons: (i) susceptibility data are not sensitive enough to definitively identify small variations in substrate specificity and (ii) the copy number of the plasmid vector can play a role in the overall level of gene expression which may influence the phenotype observed.

E. coli AmpD shares 88% identity and about 83 to 86% identity with the AmpD proteins of C. freundii and Enterobacter cloacae, respectively (19). It is interesting, however, that compared to E. coli, both C. freundii and E. cloacae carry an additional four amino acids which represent an SXXL motif at the carboxy end of the protein (19). Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of specific mutations in the carboxy terminus for both function of AmpD and overproduction of AmpC (11, 12, 19, 39). In particular, Kopp et al. have shown the importance of the last 16 amino acids of AmpD from Enterobacter cloacae for ampC overproduction (19). The current study identified the last 10 amino acids of C. freundii AmpD as an essential region for AmpD function as assayed for in the model by elevated ceftazidime MICs as an indication of the overproduction of AmpC (Fig. 1; Table 2). Insertion of PCR-generated ampD genes with truncations of the last 10, 21, or 25 codons of the carboxy terminus into the model system indicated a derepressed phenotype (Etest, >256 μg/ml). The aspartic acid residue at position 164 and two histidines located at positions 34 and 154 are necessary for zinc-binding and AmpD activity in C. freundii (11). However, this study showed that deletion of the last 10 amino acids (leaving Asp164, His34, and His154 intact) results in a MIC of >256 μg/ml, indicating their importance for enzymatic activity. The removal of these last 10 amino acids included the removal of the SXXL motif (19). NMR spectroscopy supports these data and suggests that the last 10 amino acids and the zinc-binding pocket reside in close proximity (11, 24).

CF21M is a phenotypically derepressed mutant selected from the wild-type inducible AmpC parent strain, CF21 (14). The ampD sequences for CF21 and CF21M both indicated an amino acid substitution of Arg175Ser. The ampD model confirmed that the amino acid substitution observed in the C. freundii ampD sequences was not responsible for the derepressed phenotype observed for CF21M. Amino acid substitutions in AmpR have been reported to increase AmpC production (1, 20). Recently an ampR mutation resulting in AmpC overproduction was identified in a clinical isolate of Enterobacter cloacae (18). However, in the present study no nucleotide sequence variation was observed in ampR, ampC, or the ampC-ampR intergenic region of CF21M. Surprisingly, expression analyses revealed a concomitant 11-fold decrease in ampD expression with a 403-fold increase in ampC expression in CF21M compared to CF21. The difference between decreased ampD expression and amino acid substitutions negating AmpD activity cannot be identified phenotypically. Both mechanisms would result in decreased cleavage of 1,6-anhydromuropeptide and a shift in the cytoplasmic pool concentrations between this muropeptide and UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide, resulting in overproduction of AmpC. To our knowledge, this is the first report of decreased ampD expression coinciding with ampC overproduction. The mechanism involved in the decreased ampD expression is under investigation.

The ampD model showed decreased ceftazidime MICs when ampD test genes from PAO1 and Ps164 were evaluated using JRG582 (changes in ceftazidime MICs from >256 μg/ml to 24 and 32 μg/ml, respectively [Table 2]). These data indicated that the P. aeruginosa ampD genes were expressed in E. coli. Taken together, the decrease in ceftazidime MICs and sequence data indicating a lack of amino acid substitutions compared to PAO1 suggested that these genes did complement the AmpD mutant background in JRG582. It is possible that the elevated ceftazidime MIC observed for Ps164 was due to less than optimal expression of the P. aeruginosa ampD promoter in E. coli. Alternatively, P. aeruginosa AmpD may not cleave muropeptides within E. coli as efficiently as muropeptides produced in P. aeruginosa since there is only 65% identity between the two AmpD proteins (21).

The ampD gene of P. aeruginosa Ps164 M1 contained a stop codon at position 155 and did not complement the ampD mutant phenotype of JRG582 (the ceftazidime MICs remained >256 μg/ml). However, phenotypically P. aeruginosa Ps164 M1 was partially, not fully, derepressed as the sequence and model data would suggest (D. J. Wolter, N. D. Hanson, and P. D. Lister, Abstr. 44th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C1-955, 2004). Taken together, these data indicated that the AmpD of the P. aeruginosa strain Ps164 M1 was compensated for by another mechanism within Ps164 M1. The identification of this alternative mechanism is under investigation.

It is clear that AmpD plays a role in the overproduction of AmpC in some clinical isolates (1, 12, 19, 22, 25, 39). But data presented in this study and sequence data presented by others suggest that mechanisms other than mutations within the structural ampD gene can be involved in AmpC overproduction (1, 6, 22). The model system presented in this study will be a valuable tool in elucidating these other mechanisms in different genera by eliminating or substantiating the role of amino acid substitutions within AmpD as a mechanism involved in AmpC overproduction leading to a derepressed phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Poole for supplying P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 and Tom Weber for supplying E. coli strain K-12 259. Additionally, we thank Mark Reisbig and Daniel Wolter for the design of some of the primers used in amplification of ampD. We thank Baha Abdalhamid for sequencing the ampR and ampC-ampR intergenic region of CF21M and providing real-time RT-PCR primers. DNA sequencing was performed by the Creighton University Molecular Biology Core Facility under the direction of Joseph Knezetic, and technical support was provided by Joe Choquette. Ellen Smith Moland and Jennifer Black provided technical expertise in performing initial MICs on CF21 and CF21M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagge, N., O. Ciofu, M. Hentzer, J. I. Campbell, M. Givskov, and N. Hoiby. 2002. Constitutive high expression of chromosomal beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa caused by a new insertion sequence (IS1669) located in ampD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3406-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnaud, G., G. Arlet, C. Verdet, O. Gaillot, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1998. Salmonella enteritidis: AmpC plasmid-mediated inducible beta-lactamase (DHA-1) with an ampR gene from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2352-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind, A., Y. Chong, and S. Schweighart. 1989. Extended broad spectrum beta-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae including resistance to cephamycins. Infection 17:316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergstrom, S., O. Olsson, and S. Normark. 1982. Common evolutionary origin of chromosomal beta-lactamase genes in enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 150:528-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, P. A., C. Urban, N. Mariano, S. J. Projan, J. J. Rahal, and K. Bush. 1997. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:563-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, J. I., O. Ciofu, and N. Hoiby. 1997. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis have different beta-lactamase expression phenotypes but are homogeneous in the ampC-ampR genetic region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1380-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrhardt, A. F., C. C. Sanders, J. R. Romero, and J. S. Leser. 1996. Sequencing and analysis of four new Enterobacter ampD alleles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1953-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folkesson, A., S. Eriksson, M. Andersson, J. T. Park, and S. Normark. 2005. Components of the peptidoglycan-recycling pathway modulate invasion and intracellular survival of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Cell. Microbiol. 7:147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortineau, N., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated and inducible cephalosporinase DHA-2 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gates, M. L., C. C. Sanders, R. V. Goering, and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1986. Evidence for multiple forms of type I chromosomal beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:453-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genereux, C., D. Dehareng, B. Devreese, J. Van Beeumen, J. M. Frere, and B. Joris. 2004. Mutational analysis of the catalytic centre of the Citrobacter freundii AmpD N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase. Biochem. J. 377:111-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson, N. D., and C. C. Sanders. 1999. Regulation of inducible AmpC beta-lactamase expression among Enterobacteriaceae. Curr. Pharm. Des. 5:881-894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honore, N., M. H. Nicolas, and S. T. Cole. 1986. Inducible cephalosporinase production in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae is controlled by a regulatory gene that has been deleted from Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 5:3709-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain, A., M. D. Reisbig, and N. D. Hanson. 2004. Plasmid-encoded functions compensate for the biological cost of AmpC overexpression in a clinical isolate of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:964-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs, C., J. M. Frere, and S. Normark. 1997. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible beta-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell 88:823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs, C., B. Joris, M. Jamin, K. Klarsov, J. Van Beeumen, D. Mengin-Lecreulx, J. van Heijenoort, J. T. Park, S. Normark, and J. M. Frere. 1995. AmpD, essential for both beta-lactamase regulation and cell wall recycling, is a novel cytosolic N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase. Mol. Microbiol. 15:553-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joris, B., F. De Meester, M. Galleni, S. Masson, J. Dusart, J. M. Frere, J. Van Beeumen, K. Bush, and R. Sykes. 1986. Properties of a class C beta-lactamase from Serratia marcescens. Biochem. J. 239:581-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko, K., R. Okamoto, R. Nakano, S. Kawakami, and M. Inoue. 2005. Gene mutations responsible for overexpression of AmpC beta-lactamase in some clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2955-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopp, U., B. Wiedemann, S. Lindquist, and S. Normark. 1993. Sequences of wild-type and mutant ampD genes of Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:224-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuga, A., R. Okamoto, and M. Inoue. 2000. ampR gene mutations that greatly increase class C beta-lactamase activity in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:561-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langaee, T. Y., M. Dargis, and A. Huletsky. 1998. An ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a negative regulator of AmpC beta-lactamase expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3296-3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langaee, T. Y., L. Gagnon, and A. Huletsky. 2000. Inactivation of the ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa leads to moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible AmpC beta-lactamase expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:583-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langley, D., and J. R. Guest. 1977. Biochemical genetics of the alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes of Escherichia coli K12: isolation and biochemical properties of deletion mutants. J. Gen. Microbiol. 99:263-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liepinsh, E., C. Genereux, D. Dehareng, B. Joris, and G. Otting. 2003. NMR structure of Citrobacter freundii AmpD, comparison with bacteriophage T7 lysozyme and homology with PGRP domains. J. Mol. Biol. 327:833-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindberg, F., S. Lindquist, and S. Normark. 1987. Inactivation of the ampD gene causes semiconstitutive overproduction of the inducible Citrobacter freundii beta-lactamase. J. Bacteriol. 169:1923-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔ C(T)) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miriagou, V., L. S. Tzouvelekis, L. Villa, E. Lebessi, A. C. Vatopoulos, A. Carattoli, and E. Tzelepi. 2004. CMY-13, a novel inducible cephalosporinase encoded by an Escherichia coli plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3172-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakano, R., R. Okamoto, Y. Nakano, K. Kaneko, N. Okitsu, Y. Hosaka, and M. Inoue. 2004. CFE-1, a novel plasmid-encoded AmpC beta-lactamase with an ampR gene originating from Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1151-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2004. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 14th informational supplement M100-S14. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 30.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 31.Payne, D. J., N. Woodford, and S. G. Amyes. 1992. Characterization of the plasmid mediated beta-lactamase BIL-1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 30:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitout, J. D., K. S. Thomson, N. D. Hanson, A. F. Ehrhardt, E. S. Moland, and C. C. Sanders. 1998. β-Lactamases responsible for resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis isolates recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1350-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poirel, L., M. Guibert, D. Girlich, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Cloning, sequence analyses, expression, and distribution of ampC-ampR from Morganella morganii clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preheim, L. C., R. G. Penn, C. C. Sanders, R. V. Goering, and D. K. Giger. 1982. Emergence of resistance to beta-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics during moxalactam therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:1037-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reisbig, M. D., and N. D. Hanson. 2002. The ACT-1 plasmid-encoded AmpC beta-lactamase is inducible: detection in a complex beta-lactamase background. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:557-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reisbig, M. D., A. Hossain, and N. D. Hanson. 2003. Factors influencing gene expression and resistance for Gram-negative organisms expressing plasmid-encoded ampC genes of Enterobacter origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1141-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders, C. C., and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1992. β-Lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria: global trends and clinical impact. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:824-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders, C. C., and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1979. Emergence of resistance to cefamandole: possible role of cefoxitin-inducible beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 15:792-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stapleton, P., K. Shannon, and I. Phillips. 1995. DNA sequence differences of ampD mutants of Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2494-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomson, K. S., and E. Smith Moland. 2000. Version 2000: the new beta-lactamases of Gram-negative bacteria at the dawn of the new millennium. Microbes Infect. 2:1225-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuomanen, E., S. Lindquist, S. Sande, M. Galleni, K. Light, D. Gage, and S. Normark. 1991. Coordinate regulation of beta-lactamase induction and peptidoglycan composition by the amp operon. Science 251:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiedemann, B., H. Dietz, and D. Pfeifle. 1998. Induction of beta-lactamase in Enterobacter cloacae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27(Suppl. 1):S42-S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolter, D. J., N. D. Hanson, and P. D. Lister. 2005. AmpC and OprD are not involved in the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates overexpressing the mexCD-oprJ efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4763-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]