Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae is subject to phase variation mediated by changes in the length of simple sequence repeat regions within several genes, most of which encode either surface proteins or enzymes involved in the synthesis of lipopolysaccharides (LPS). The translational repeat regions that have been described thus far all consist of tandemly repeated tetranucleotides. We describe an octanucleotide repeat region within a putative LPS biosynthetic gene, losA. Approximately 20 percent of nontypeable H. influenzae strains contain copies of losA and losB in a genetic locus flanked by infA and ksgA. Of 30 strains containing losA at this site, 24 contained 2 tandem copies of the octanucleotide CGAGCATA, allowing full-length translation of losA (on), and 6 strains contained 3, 4, 6, or 10 tandem copies (losA off). For a serum-sensitive strain, R3063, with losA off (10 repeat units), selection for serum-resistant variants yielded a heterogeneous population in which colonies with increased serum resistance had losA on (2, 8, or 11 repeat units), and colonies with unchanged sensitivity to serum had 10 repeats. Inactivation of losA in strains R3063 and R2846 (strain 12) by insertion of the cat gene decreased the serum resistance of these strains compared to losA-on variants and altered the electrophoretic mobility of LPS. We conclude that expression of losA, a gene that contributes to LPS structure and affects serum resistance, is determined by octanucleotide repeat variation.

Several species of bacteria, including Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, N. gonorrhoeae, and Helicobacter pylori, are able to generate genetic diversity via loci containing tandem repeats of single nucleotides or short multiple-nucleotide sequences. Such loci are also known as simple sequence repeats, microsatellites, or contingency loci (2, 32). These genetic loci are hypermutable and undergo the addition or deletion of repeat units during replication, apparently through slipped-strand mispairing. If the tandem repeats are within a gene, the addition or deletion of repeating units can change the reading frame downstream of the repeats with respect to the frame initiated by the start codon; this can result in premature termination of translation or in extension of the open reading frame to the full length of a previously interrupted gene. This ability to turn such genes on or off results in phenotypic phase variation. A population of organisms can adapt to changes in their microenvironment based on their ability to translate full-length functional proteins of different phase-variable genes. A repeat region with this function could in principle be of any length that is not a multiple of three. In Neisseria spp., phase variation is mediated by tandem dinucleotides and repeated single nucleotides as well as by tandem tetranucleotide and pentanucleotide repeats (20). However, in H. influenzae, all of the translational tandem repeat regions capable of mediating phase variation that have been described to date are tetranucleotides. While mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats exist in H. influenzae genome sequences, those that have been identified so far are between genes. Intergenic dinucleotide and heptanucleotide tandem repeats have been shown to mediate phase variation by affecting transcription of the hif and hmw loci, respectively (5, 31). van Belkum et al. searched the published sequence of the H. influenzae strain Rd KW20 genome for tandem repeat regions and identified one trinucleotide repeat region, two pentanucleotide repeat regions, and three hexanucleotide repeat regions (30) in addition to the tetranucleotide repeat regions already described (14). This analysis did not find repeat regions with longer repeat units.

Many of the phase-variable genes that have been characterized for H. influenzae encode enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharides (LPS). As a result, a culture of H. influenzae is likely to be a population heterogeneous in terms of LPS structure, as individual bacteria differ in expression of one or more glycosyl transferases and of the enzyme required for the addition of phosphocholine to LPS molecules. In addition to having heterogeneity in LPS structure as a result of varying expression of phase-variable genes in any given strain, H. influenzae strains differ in LPS structure as a result of possessing different complements of LPS biosynthetic genes. We recently described the heterogeneity of a genetic locus present in most nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHI) isolates. This locus, flanked by infA and ksgA, contains genes for either the glycosyl transferases lic2B and lic2C or the glycosyl transferases losA and losB (Fig. 1) (7). The lic2B and lic2C genes were first identified in a type b strain, RM7004, and their variable presence in NTHI strains had been studied previously (13, 24). Putative functions for losA and losB were assigned based on data for similar genes in Haemophilus ducreyi (29). While screening clinical isolates for lic2BC and losAB, we noted that the losA gene in different H. influenzae isolates differed in the number of copies of a tandemly repeated eight-nucleotide sequence. We now present evidence suggesting that losA expression is phase variable and affects the resistance of bacteria to complement-mediated killing by normal human serum. This is the first example of phase variation mediated by tandem octanucleotide repeats.

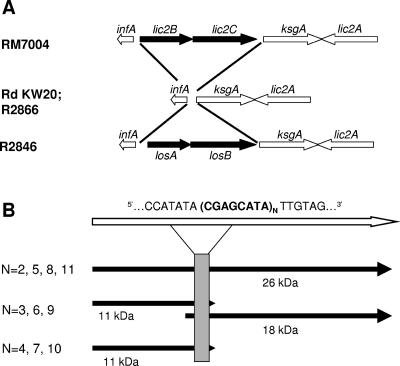

FIG. 1.

(A) Heterogeneity of the infA-ksgA region in H. influenzae (7). We previously found in a study of 99 NTHI isolates that 31 lack this island, as depicted for strains Rd KW20 and R2866; 45 isolates contain lic2B and lic2C, as shown for strain RM7004 (16, 20); and 17 contain losA and losB, as shown for strain R2846. (B) Effect of number of octanucleotide repeat units (N) on the predicted size of potential protein products of the losA gene. The open arrow at the top represents the nucleotide sequence, and the black arrows represent potential translation products. The gene is considered as on when N is 2, 5, 8, or 11, as these numbers result in an open reading frame of 675 bp or longer, potentially resulting in a 26-kDa translation product. With other numbers of repeat units, the open reading frame is truncated just downstream of the repeat region (shown as a shaded rectangle in the center of the figure).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Strains Rd KW20 and R2866, used as controls in serum bactericidal assays, are well-characterized laboratory isolates (8, 22). R3063, a nontypeable H. influenzae strain isolated in 1995 from the blood of a 69-year-old patient, was obtained from Carol Shaw, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Canada. R2846 is also known as strain 12 (1) and is the strain in which the losAB locus was first identified in H. influenzae (7). Other NTHI strains screened for the presence of the losAB locus flanked by infA and ksgA were from the laboratory collections of A. L. Smith and J. R. Gilsdorf. Isolates in which losA was identified are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were cultivated at 37°C on chocolate agar supplemented with 1% Isovitalex (Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) and with bacitracin 5 U/ml or in Difco brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson and Co.) supplemented with hemin (10 μg/ml) and β-NAD (10 μg/ml) (sBHI) and with agar for solid sBHI plates.

TABLE 1.

Nontypeable H. influenzae strains containing losA

| Clinical source | Strain(s) (previous designation) | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ear aspirate | R2846 (strain 12) | 1 |

| C464, R3140 | ALS laboratory collectiona | |

| G123, G423, G922, G1023, G1822, Mr37, Mr49, Mr50 | JRG laboratory collection | |

| Nasopharynx | R3019, R3021, R3022, R3261 | ALS laboratory collectiona |

| 22121, 26225, 38121, 41021, B01-21, F05-21, H08-25 | JRG laboratory collection | |

| Blood or CSFb | R3171, R3583 | ALS laboratory collectiona |

| R3058 (Z701), R3063 (Z306), R3066 (Z34) | C. Shaw, Vancouver, BC, Canada | |

| R3576 (773) | R. F. Jacobs, Little Rock, AR; 23 | |

| Bronchial aspirate | R3001 | 19 |

| R3179 (AAr75) | JRG laboratory collection |

These strains were characterized in a previous study (7).

Isolates R3058 and R3066 are from newborns; isolate R3063 is from an adult. Otherwise, blood or cerebrospinal fluid isolates were from children 3 months of age or older. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

DNA preparation and analysis.

Genomic DNA was prepared using a DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA). DNA was prepared from individual colonies by boiling a small amount of bacterial growth for 10 min in a 10% suspension of Chelex (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and then pelleting the Chelex. The supernatant contained genomic DNA and was used as the template in PCRs.

The presence of a 2.2-kb region flanked by infA and ksgA was determined by PCR across the infA-ksgA junction by using primers described previously (7). The genetic content of the 2.2-kb region was determined either by sequencing or by PCR using primers infA and losB-R to detect losAB and primers lic2B-F and lic2BA to detect lic2BC, as described previously (7). Routine PCR was carried out using Biolase DNA polymerase (Bioline USA, Randolph, MA) with the following amplification protocol: reaction tubes were incubated at 94°C for 2 min and then for 36 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min per kb predicted product.

The mdh gene was amplified and sequenced as for multilocus sequence typing (21).

The following primers were used to amplify the octanucleotide repeat region and 200 downstream bp: forward (5′-GCG CAA TCA GCC ATA TAC GAG CAT-3′) and reverse (5′-GGG CTC TAT AAT GAG CAA GTC GAT AGC C-3′). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 12 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 50°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s; 20 cycles of 89°C for 15 s, 50°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s; and 72°C for 10 min. The reverse primer was used for sequencing. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). For detection of amplified products by GeneMapper (see below), the forward primer was labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein.

Analysis of octanucleotide repeat region by fragment size analysis. (i) Bioanalyzer.

The PCR-amplified products were sized on a bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) using DNA 500 chips according to the manufacturer's protocol. For eight strains in which the losA gene contained two octanucleotide repeats (as determined by sequencing), the PCR product sizes calculated by the Agilent software ranged from 220 to 226 bp. For five strains containing three octanucleotide repeats, the calculated sizes for the PCR products ranged from 229 to 232 bp. The bioanalyzer was thus able to distinguish accurately between PCR products containing two octanucleotide repeats and those containing three. Based on this observation, 17 additional strains that yielded PCR products with calculated sizes ranging from 220 to 224 bp were recorded as containing two octanucleotide repeats. Three strains yielded PCR products with calculated sizes of 239, 255, and 297 bp; on sequencing, these were found to contain 4, 6, and 10 octanucleotide repeats, respectively.

(ii) GeneMapper.

In order to evaluate the heterogeneity of a population of bacteria, PCR was carried out on DNA prepared from multiple individual colonies. The octanucleotide repeat region was amplified as described above by using a primer set in which the forward primer was labeled to allow detection of products within gels by fluorescence. Amplicons were resolved on automated DNA sequencing gels and analyzed with the GeneMapper system software (Applied Biosystems, San Diego, CA), which allows precise determination of fragment sizes, i.e., within 1 bp. Amplicons differing by 8 bp could readily be distinguished, and the on or off state of losA could be determined by comparison of these product sizes with the size of the repeat region amplified from a genomic DNA preparation for which losA had been sequenced.

Insertional mutagenesis of losA.

A 1,737-bp PCR product containing the losA gene was amplified from genomic DNA of R2846 by using primers losAko F (5′-CGG TGT AAC GTT CGA TCA TAC CTG-3′) and losAko R (5′-CTA AGC ACG ATG GTA GGG TCA ATG-3′), ligated to the pCR 2.1 cloning vector (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and transformed into Escherichia coli. The cloned losA gene was cut at a unique SspI site, treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Invitrogen), and blunt-end ligated to a 1,336-bp DNA fragment containing the cat gene, which had been recovered from plasmid pUCΔEcat (4) by HincII digestion and gel purification. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli, and a plasmid conferring chloramphenicol resistance (plosAcat) was isolated.

Strain R2846 was made competent by incubation in medium M-IV (11), transformed with plasmid plosAcat that had been linearized by digestion with BglII, and plated on chocolate agar containing chloramphenicol (2 μg/ml). Six chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were retained, and interruption of chromosomal losA by cat was verified by PCR and sequencing. A 4-kb region including the cat-interrupted losA gene in R2846 was amplified using primers ksgA and losAko F, and the product was transformed into isolate R3063N-T (a colony of R3063 recovered after serum treatment, in which the losA gene contains 11 repeats). Two losA insertional mutants of R3063 were obtained.

Resistance of bacteria to complement-mediated killing.

A microtiter assay of serum resistance was carried out as described previously (7). Briefly, bacteria (2,000 CFU/ml) were incubated in serially diluted serum (pooled from healthy human volunteers) for 30 min at 37°C and then plated to determine numbers of surviving bacteria. The concentration of serum that killed 50% of the inoculum was calculated using XLfit 4.1 (ID Business Solutions, Guildford, United Kingdom) and is referred to as the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the serum for that strain.

Strain R3063 was enriched for serum-resistant variants by incubating cells in 40% serum for 30 min, washing bacteria in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% gelatin, and allowing surviving cells to grow to mid-log phase in sBHI. The enrichment process was repeated, and survivors of the second selection were stored at −80°C. A mock enrichment was carried out in parallel using serum that had been heat inactivated by incubation at 55°C for 30 min. The frozen stock of serum-selected R3063 cells was subcultured onto chocolate agar, and 36 single colonies were selected, subcultured, and frozen as separate freezer stocks.

Analysis of LPS by SDS-PAGE.

Bacterial cultures were prepared for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) by proteinase K digestion and ethanol precipitation (15). The Tris-Tricine electrophoresis system of Lesse et al. was used (17), with a resolving gel of approximately 12 cm. SeeBlue prestained standard molecular weight markers (Invitrogen) were included as a reference for mobility. LPS was visualized by silver staining (28).

Sequence analysis and calculations.

The complete genome sequence of H. influenzae strain Rd KW20 and the incomplete sequences of strains R2846 and R2866 were accessed through the microbial genome database of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi). The nucleotide sequence of losA and the surrounding region in strain R2846 has NCBI accession number DQ007026 (7). A search of the Rd KW20 genome sequence for tandem repeats was carried out using the Tandem Repeats Finder at http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html (3). The number of times that two consecutive repeats of any eight-base sequence would be expected to occur by chance in the 1.83-Mbp Rd KW20 genome was calculated as follows: (1.83 × 106) × 0.258 = 27.9. This result is an approximation, since the calculation is based on the assumption that at any base the probability of any specific nucleotide is 0.25. The Mann-Whitney nonparametric test for calculating the significance of the difference between the distributions of two independent samples was performed online using the VassarStats website for statistical calculation (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html).

RESULTS

Identification of octanucleotide repeat region within losA.

We previously described the identification of 12 isolates containing losAB in a collection of 72 clinical NTHI isolates (7). Evaluation of 99 additional clinical isolates resulted in identification of 18 additional strains containing losAB. The losA sequences were highly conserved, with DNA sequences >90% similar to that of losA in strain R2846. The sequences differed, however, in that they contained variable numbers of an octanucleotide sequence, 5′-CGAGCATA-3′, tandemly repeated in the middle of the gene. The number of repeats affected the size of the potential translation product (Fig. 1; Table 2). In 24 isolates, the losA gene had only two complete octanucleotide sequences, and the predicted peptide was 26 kDa. One isolate was found to have 4 repeats, and one isolate (R3063) had 10. In these two isolates, the open reading frame contained a stop codon just downstream of the repeat region, with the predicted peptide being 11 kDa. For three isolates with three octanucleotide repeats and one isolate with six repeats, the open reading frame was also predicted to encode a protein of only 11 kDa. In these isolates, a second open reading frame had a potential start site just upstream of the repeat region, with a potential ribosome-binding site (AGGTG) 13 bp upstream of the ATG. Translation of this second open reading frame would yield a peptide with a predicted size of 18 kDa. Although we have no direct evidence of production of the LosA protein, it seems likely that changes in the length of the octanucleotide repeat region affect losA expression at the level of translation. This is supported by data in the following sections on the correlation between phenotype and losA octanucleotide repeat number. The 26-kDa predicted amino acid sequence of losA from NTHI strain R2846 is homologous (predicted amino acid sequence similarity of 77%) to a 26-kDa β-1,4-galactosyltransferase that has been characterized for H. ducreyi (29). It is likely that in NTHI, the 26-kDa product is active LosA, and genes with octanucleotide numbers consistent with this product are considered to be on.

TABLE 2.

Heterogeneity in octanucleotide repeat region of losA

| Strain(s) | No. of octanucleotide repeat units in losA | Sizes of predicted losA translation products (kDa) | On or off |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22121, 26225, 38121, 41021, B01-21, C464, F05-21, H08-25, G123, G423, G922, G1822, Mr37, Mr49, Mr50, R2846, R3001, R3019, R3058, R3066, R3171, R3179, R3576, R3583 | 2 | 26 | On |

| G1023, R3021, R3022 | 3 | 11 + 18 | Off |

| R3261 | 4 | 11 | Off |

| R3140 | 6 | 11 + 18 | Off |

| R3063 | 10 | 11 | Off |

Intrastrain heterogeneity in serum resistance correlates with on versus off state of losA.

We sought evidence that alteration of environmental conditions would select for variants that differed in on/off state from the parent population. Strain R3063 was chosen for these studies because it contains the longest losA repeat region that we observed and was therefore considered more likely to undergo phase variation (6). Colonies of R3063 were uniformly losA off, with 10 copies of the octanucleotide in each of 20 colonies studied (Table 3). Incubation of R3063 with pooled normal human serum yielded a population, designated R3063N, that was heterogeneous in the length of the octanucleotide repeat region. We studied 36 randomly chosen single colonies of R3063N (Table 3). Of these, seven were similar to the parent population in containing 10 repeat units (losA off). In 20 clones, the losA gene, containing either 2 or 11 repeats, was on. For the remaining nine subclones, the PCR-amplified octanucleotide repeat regions were mixtures of 2, 8, 10, and 11 repeats. When these subclones were restreaked and single colonies analyzed, most colonies contained repeat regions of a single length, corresponding to one of these repeat numbers, but a small number of other colonies contained mixtures even after two single-colony passages.

TABLE 3.

Heterogeneity of octanucleotide repeat region of losA in individual colonies of R3063 and serum-selected R3063N

| Strain | No. of colonies | No. of octanucleotide repeat units in losA | Size(s) of predicted losA translation products (kDa) | On or off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R3063 | 20 | 10 | 11 + 18 | Off |

| R3063N | 8 | 2 | 26 | On |

| 7 | 10 | 11 + 18 | Off | |

| 12 | 11 | 26 | On | |

| 9 | Mixedb | NAa | NA |

NA, not applicable.

DNA from single colonies of two of the mixed isolates was isolated, and numbers of repeats were determined by fragment analysis, which showed that the population was composed of 10 repeats, as in the parent R3063 (off), and of 2, 8, and 11 repeats (on). The DNA from the other seven mixed isolates was analyzed by fragment analysis and showed major peaks corresponding to various mixtures of 2, 10, and 11 repeats.

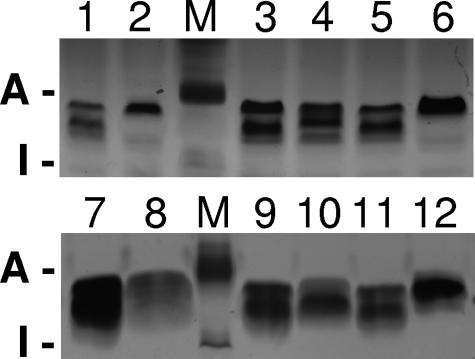

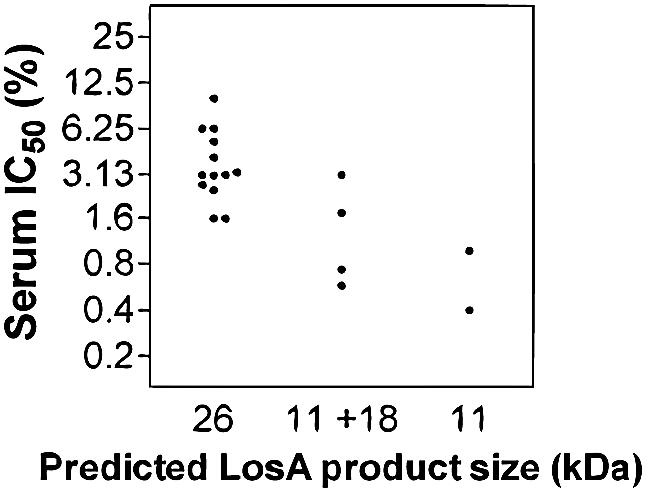

Clones with losA on were found to be significantly (P = 0.0002) more resistant to serum, with a geometric mean serum IC50 of 1.3%, than those with losA off, which had a mean serum IC50 of 0.36% (Fig. 2). The wide range of IC50 for the losA-on colonies (0.48% to 5.7%) suggests that the colonies were heterogeneous in expression of other genes affecting serum resistance. This is not surprising considering that several of the phase-variable genes involved in LPS synthesis are known to affect serum resistance. Survivors of serum treatment may differ from the parent population in one or more phase-variable genes besides losA. It was surprising to see that losA was on in all of the colonies for which serum IC50 was over 0.5%. We would have expected that multiple LPS structures might be associated with serum resistance and that some of those structures could be synthesized even with losA off.

FIG. 2.

Individual colonies of serum-treated R3063 (R3063N) were grown up to test for serum resistance and to determine losA phase state. As described in the text and in Table 3, for colonies scored as on, the losA gene contained either 2 repeats (8 colonies) or 11 repeats (12 colonies) of the octanucleotide. For colonies scored as off, the losA gene contained 10 repeats (seven colonies).

We considered the possibility that our stock of R3063 was contaminated with a different serum-resistant strain of NTHI and that incubation in serum had simply selected for that strain. This possibility was evaluated by determining the sequence of the mdh gene in the parent strain and in each of the subcultures. Over 100 mdh sequences have been reported for the 374 strains in the H. influenzae database at http://www.mlst.net (21). We found that all of the R3063N subcultures were identical to the parent population at this locus, strongly suggesting that they were derived from a single isolate and were not the result of a mixed culture.

Inactivation of losA increases serum sensitivity.

In the experiment described above, we noted a correlation between serum resistance and the on/off state of losA. In order to evaluate more directly the role of losA in serum resistance, we inactivated the losA gene in two isolates for which losA was on: wild-type R2846 and colony T of serum-treated R3063. In each case the serum IC50 of the losA mutants was nearly 10-fold lower than that of the parent (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Inactivation of losA increases sensitivity to serum

| Straina | Mean IC50 (range); no. of assaysb |

|---|---|

| R2846 parent | 5.75 (1.92-12.43); 4 |

| R2846 losA KO 1 | 0.74 (0.69-0.78); 4 |

| R2846 losA KO 2 | 0.66 (0.53-0.74); 3 |

| R2846 losA KO 3 | 0.51 (0.44-0.56); 3 |

| R2846 losA KO 4 | 0.63 (0.53-0.75); 2 |

| R2846 losA KO 5 | 0.74 (0.66-0.79); 3 |

| R2846 losA KO 6 | 0.68 (0.65-0.73); 3 |

| R3063N-T | 12.01 (9.36-14.91); 4 |

| R3063N-T losA KO 1 | 1.79 (1.10-2.72); 4 |

| R3063N-T losA KO 2 | 0.97 (0.51-1.86); 3 |

| Rd KW20 | 0.50 (0.38-0.72); 4 |

| R2866 | >25.0; 4 |

R2846 was transformed with a construct in which the losA gene was interrupted by a chloramphenicol resistance cassette. Six independent transformants were assayed. R3063N T is derived from a single colony in which losA contained 11 repeats. It was similarly transformed, and data from two independent losA mutants are shown. Rd KW20 and R2866 were included in all assays as controls for a serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strain, respectively (7). KO, knockout.

The IC50 is the serum concentration (expressed as a percentage) that kills half of the bacterial inoculum in 30 min. Each strain or mutant was assayed two, three, or four times. The geometric mean IC50 and the range are shown.

Evidence that losA expression affects LPS structure.

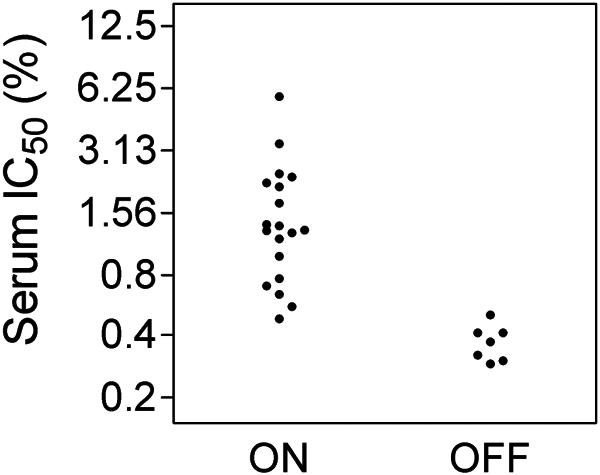

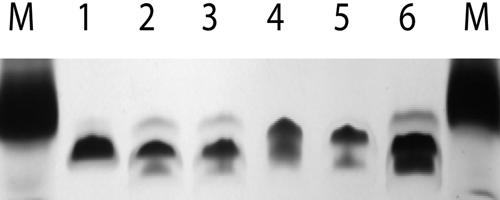

Proteinase K digests were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). LPS of the losA mutants of R2846 and R3063 migrated slightly faster than that of their losA+ parents. We also examined 12 of the R3063N subcultures by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4). For six preparations for which losA was off, the LPS structures appeared similar, containing two predominant bands of approximately equal densities. Each of the six preparations with losA on had an altered pattern: four had a single predominant band, similar in apparent size to the upper band of the off preparations. The remaining two preparations with losA on had two predominant bands, the lower of which had slightly reduced mobility compared to the lower band of the off preparations. The heterogeneity of these subcultures is not surprising. It is likely that they vary in terms of the on/off state of other phase-variable genes affecting LPS synthesis, such as lic1, lic2A, and lic3A, etc. (32).

FIG. 3.

Effect of losA inactivation on mobility of LPS. Proteinase K digests of bacterial lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the LPS was detected by silver staining. Lanes marked M contain protein molecular weight markers; the visible band is aprotinin (7 kDa). Lanes: 1, wild-type R2846; 2 and 3, losA insertion mutants of R2846; 4, R3065N colony T; 5 and 6, the corresponding losA insertion mutants.

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE of LPS from cultures derived from single colonies of R3063N. Lanes marked M contain protein molecular weight markers; the positions of aprotinin (A; 7 kDa) and insulin β chain (I; 4 kDa) are indicated to the left of each panel. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 are from colonies with losA off; lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 are from colonies with losA on.

Serum resistance of losAB-containing strains correlates with on versus off state of losA.

The IC50s of normal human serum for 18 losAB-containing isolates were found to range from 0.4% to 10%, with a geometric mean of 2.3% (Fig. 5). A similar range of serum resistance was found in a previous study using 53 clinical NTHI isolates, including 14 of the strains used in the present study (7). Thus, the presence or absence of the losAB locus does not correlate with serum resistance. However, there was a correlation (P = 0.01) between serum resistance of a strain and the on versus off state of its losA gene. The four most sensitive strains, those for which the serum IC50 was <1%, were all losAB-containing strains in which the losA gene was off (Fig. 5). Although not all off strains were unusually serum sensitive, this observation suggests that for these strains, the on/off state of losA is a major factor in serum resistance.

FIG. 5.

Susceptibility of bacteria to killing by pooled normal human serum. Eighteen clinical isolates with losAB flanked by infA and ksgA and varying in the number of octanucleotide repeat units (Table 2; Fig. 1B) are shown.

Identification of octanucleotide repeat regions in the Rd KW20 genome.

Previous efforts to identify all potential phase-variable genes in the H. influenzae Rd KW20 genome sequence have searched for regions with three or more repeats (30). The data presented above indicate that a gene that is phase variable may have only two repeats in some strains. In a search for other potential phase-variable genes, we scanned the Rd KW20 genome for hitherto-unreported tandem repeat regions by using search parameters permitting identification of heptanucleotide and octanucleotide repeat regions with as few as two complete repeat units. Thirty regions containing two repeats of an octamer and 25 regions containing two repeats of a heptamer, essentially the numbers that would be expected by chance, were identified.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here provide the first evidence of phase variation in H. influenzae mediated by changes in length of an intragenic octanucleotide tandem repeat region. In all intragenic tandem repeat regions identified previously, the repeated unit is a tetramer (12, 30). We did not study the function of losA in detail. Based on sequence similarity to the H. ducreyi galactosyltransferase gene losA, we propose that it is a glycosyltransferase, probably one involved in LPS biosynthesis (29). This is supported by differences in the electrophoretic mobility of LPS in losA-expressing variants and that in losA-off variants or losA-deficient mutants. The gene adjacent to losA in the H. influenzae strains we studied is homologous to H. ducreyi losB, which is reported to catalyze the addition of heptose to the oligosaccharide region of LPS (9, 29). H. influenzae strains are heterogeneous in LPS structure. Heptose has been reported to be present in oligosaccharides of a small number of strains but is lacking in strain Rd KW20, the only sequenced strain for which LPS structure has been studied (18, 25). Structural studies of LPS from R2846 and defined mutants thereof will allow us to evaluate the role of losAB and other putative LPS biosynthetic genes in synthesis of the heptose-containing oligosaccharides.

For both strains R2846 and R3063, the ability to express losA affected serum resistance, as has been noted for several other LPS alterations in other strains (10, 26, 33). This property allowed us to select losA-on variants of R3063 from a population that was predominantly losA off. Formal proof of losA phase variation would require determination of the rate of on-to-off and off-to-on switching by using antibody reactivity or reporter gene activity to distinguish phase states (6, 16, 27).

Approximately 25% of R3063 colonies recovered after serum treatment were heterogeneous with regard to the number of repeats within losA, and some of the progeny of these colonies were also mixed. This suggests a high degree of instability in the repeat region. Whereas tetranucleotide repeat regions usually change in length by only one or two repeat units, several of the colonies recovered after serum treatment were eight repeat units shorter than the starting population. These colonies contained only two repeat units, and it seems likely that elongation of this repeat region will be very infrequent. For a tetranucleotide repeat region derived from the phase-variable gene mod, it was shown that the length of the repeat tract increased the frequency of on/off switching (6). If the same is true of the octanucleotide repeat region, it may be that a losA gene with only two repeats is effectively locked on.

The apparent ease with which a long repeat region (10 octanucleotide repeat regions) was replaced by a two-repeat region may help to explain why long repeat regions were rare among the strains we studied. Of 30 clinical isolates possessing losAB flanked by infA and ksgA, only 6 had more than two octanucleotide repeat units. All of these were out of frame. The losA-off state may provide a selective advantage in vitro and in certain environments within the host. However, the fact that most of the losAB-containing strains we studied had only two repeat units suggests that the ability of H. influenzae to switch between losA on and losA off is not critical for either asymptomatic colonization or disease.

For nearly all phase-variable H. influenzae genes studied previously, the repeat region is easily recognizable, containing seven or more repeat units in all strains that have the gene (30). The exception is the DNA methylase mod, which has 32 tetranucleotide repeats in the sequenced strain Rd KW20, but tetranucleotide repeat regions were found in only 13 of 23 ear aspirate isolates (6). losA appears to be a second example of a gene that is phase variable in only a fraction of the strains possessing the gene. The tandem repeat region in losA was not recognized until losA sequences from several strains were aligned and noted to vary at a specific site. It seems possible that there are additional H. influenzae phase-variable genes that have not been recognized because the repeat regions are short in the strains in which the genes have been sequenced. With this in mind, we searched the sequenced H. influenzae genomes for additional genes containing two or more tandemly repeated copies of an octanucleotide region. The number we identified (30 in the Rd KW20 sequence) is no greater than that which would be expected by chance. None of these genes had more than two repeats in any of the sequenced genomes, and it is not possible without further study to determine whether any mediates phase variation.

In summary, we studied 30 NTHI isolates containing an losAB locus flanked by infA and ksgA. We noted intrastrain and interstrain variation in the numbers of tandemly repeated octanucleotide sequences within losA. Our data suggest that changes in the length of this octanucleotide repeat region mediate phase-variable expression of an LPS structure that affects serum resistance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI 44002, AI 46512, and DC 005833 to A.L.S.; grant DC 05840 to J.R.G.; grant DC 006585 to K.W.M.; and a grant from the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust to the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute.

We thank G. W. Erwin, Jr., for assistance with probability calculations.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Barenkamp, S. J., and E. Leininger. 1992. Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 60:1302-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayliss, C. D., D. Field, and E. R. Moxon. 2001. The simple sequence contingency loci of Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. J. Clin. Investig. 107:657-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson, G. 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:573-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daines, D. A., and A. L. Smith. 2001. Design and construction of a Haemophilus influenzae conjugal expression system. Gene 281:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawid, S., S. J. Barenkamp, and J. W. St. Geme III. 1999. Variation in expression of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW adhesins: a prokaryotic system reminiscent of eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1077-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bolle, X., C. D. Bayliss, D. Field, T. van de Ven, N. J. Saunders, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2000. The length of a tetranucleotide repeat tract in Haemophilus influenzae determines the phase variation rate of a gene with homology to type III DNA methyltransferases. Mol. Microbiol. 35:211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erwin, A. L., K. L. Nelson, T. Mhlanga-Mutangadura, P. J. Bonthuis, J. L. Geelhood, G. Morlin, W. C. Unrath, J. Campos, D. W. Crook, M. M. Farley, F. W. Henderson, R. F. Jacobs, K. Muhlemann, S. W. Satola, L. van Alphen, M. Golomb, and A. L. Smith. 2005. Characterization of genetic and phenotypic diversity of invasive nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 73:5853-5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson, B. W., A. A. Campagnari, W. Melaugh, N. J. Phillips, M. A. Apicella, S. Grass, J. Wang, K. L. Palmer, and R. S. Munson, Jr. 1997. Characterization of a transposon Tn916-generated mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi 35000 defective in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 179:5062-5071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin, R., A. D. Cox, K. Makepeace, J. C. Richards, E. R. Moxon, and D. W. Hood. 2005. Elucidation of the monoclonal antibody 5G8-reactive, virulence-associated lipopolysaccharide epitope of Haemophilus influenzae and its role in bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. Infect. Immun. 73:2213-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herriott, R. M., E. M. Meyer, and M. Vogt. 1970. Defined nongrowth media for stage II development of competence in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 101:517-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood, D. W., M. E. Deadman, T. Allen, H. Masoud, A. Martin, J. R. Brisson, R. Fleischmann, J. C. Venter, J. C. Richards, and E. R. Moxon. 1996. Use of the complete genome sequence information of Haemophilus influenzae strain Rd to investigate lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 22:951-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hood, D. W., M. E. Deadman, A. D. Cox, K. Makepeace, A. Martin, J. C. Richards, and E. R. Moxon. 2004. Three genes, lgtF, lic2C and lpsA, have a primary role in determining the pattern of oligosaccharide extension from the inner core of Haemophilus influenzae LPS. Microbiology 150:2089-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood, D. W., M. E. Deadman, M. P. Jennings, M. Bisercic, R. D. Fleischmann, J. C. Venter, and E. R. Moxon. 1996. DNA repeats identify novel virulence genes in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11121-11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones, P. A., N. M. Samuels, N. J. Phillips, R. S. Munson, Jr., J. A. Bozue, J. A. Arseneau, W. A. Nichols, A. Zaleski, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 2002. Haemophilus influenzae type b strain A2 has multiple sialyltransferases involved in lipooligosaccharide sialylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14598-14611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura, A., C. C. Patrick, E. E. Miller, L. D. Cope, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 1987. Haemophilus influenzae type b lipooligosaccharide: stability of expression and association with virulence. Infect. Immun. 55:1979-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesse, A. J., A. A. Campagnari, W. E. Bittner, and M. A. Apicella. 1990. Increased resolution of lipopolysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides utilizing tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Immunol. Methods 126:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Månsson, M., D. W. Hood, E. R. Moxon, and E. K. Schweda. 2003. Structural diversity in lipopolysaccharide expression in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Identification of l-glycerol-d-manno-heptose in the outer-core region in three clinical isolates. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:610-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin, K., G. Morlin, A. Smith, A. Nordyke, A. Eisenstark, and M. Golomb. 1998. The tryptophanase gene cluster of Haemophilus influenzae type b: evidence for horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 180:107-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin, P., T. van de Ven, N. Mouchel, A. C. Jeffries, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2003. Experimentally revised repertoire of putative contingency loci in Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58: evidence for a novel mechanism of phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 50:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meats, E., E. J. Feil, S. Stringer, A. J. Cody, R. Goldstein, J. S. Kroll, T. Popovic, and B. G. Spratt. 2003. Characterization of encapsulated and noncapsulated Haemophilus influenzae and determination of phylogenetic relationships by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1623-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nizet, V., K. F. Colina, J. R. Almquist, C. E. Rubens, and A. L. Smith. 1996. A virulent nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. J. Infect. Dis. 173:180-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Neill, J. M., J. W. St. Geme III, D. Cutter, E. E. Adderson, J. Anyanwu, R. F. Jacobs, and G. E. Schutze. 2003. Invasive disease due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae among children in Arkansas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3064-3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettigrew, M. M., B. Foxman, C. F. Marrs, and J. R. Gilsdorf. 2002. Identification of the lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis gene lic2B as a putative virulence factor in strains of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae that cause otitis media. Infect. Immun. 70:3551-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards, J. C., A. D. Cox, E. K. Schweda, A. Martin, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2001. Structure and functional genomics of lipopolysaccharide expression in Haemophilus influenzae. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 491:515-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Severi, E., G. Randle, P. Kivlin, K. Whitfield, R. Young, R. Moxon, D. Kelly, D. Hood, and G. H. Thomas. 2005. Sialic acid transport in Haemophilus influenzae is essential for lipopolysaccharide sialylation and serum resistance and is dependent on a novel tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1173-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srikhanta, Y. N., T. L. Maguire, K. J. Stacey, S. M. Grimmond, and M. P. Jennings. 2005. The phasevarion: a genetic system controlling coordinated, random switching of expression of multiple genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:5547-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tullius, M. V., N. J. Phillips, N. K. Scheffler, N. M. Samuels, J. R. Munson, Jr., E. J. Hansen, M. Stevens-Riley, A. A. Campagnari, and B. W. Gibson. 2002. The lbgAB gene cluster of Haemophilus ducreyi encodes a beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase and an alpha-1,6-dd-heptosyltransferase involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Infect. Immun. 70:2853-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Belkum, A., S. Scherer, W. van Leeuwen, D. Willemse, L. van Alphen, and H. Verbrugh. 1997. Variable number of tandem repeats in clinical strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 65:5017-5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Ham, S. M., L. van Alphen, F. R. Mooi, and J. P. van Putten. 1993. Phase variation of H. influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell 73:1187-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiser, J. N. 2000. The generation of diversity by Haemophilus influenzae. Trends Microbiol. 8:433-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiser, J. N., and N. Pan. 1998. Adaptation of Haemophilus influenzae to acquired and innate humoral immunity based on phase variation of lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 30:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]