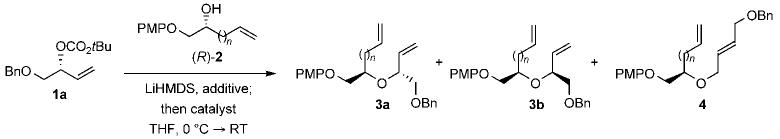

The transition-metal-catalyzed intermolecular allylic etherification is a fundamentally important cross-coupling strategy for the construction of enantiomerically enriched allylic ethers.[1] Although there are numerous examples of the use of simple primary alcohols as nucleophiles, secondary or tertiary alcohols have been used in relatively few studies,[2] partially because of the poor nucleophilicity of these alcohols and the high basicity of the corresponding alkali-metal alkoxides. In response to these underlying problems, we recently reported a regioselective and enantiospecific rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification with copper(I) alkoxides as nucleophiles.[3] The transmetalation of an alkali-metal alkoxide served to diminish its basicity, thereby promoting the etherification of a soft metal—allyl electrophile.[4]

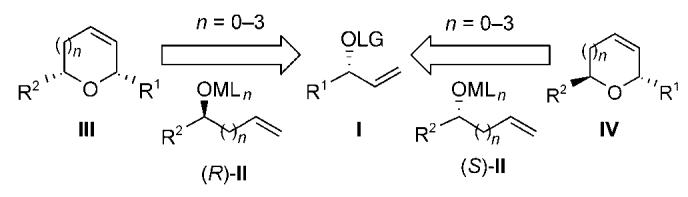

Herein, we now describe a two-step stereodivergent synthesis of cyclic ethers. The stereospecific etherification of the acyclic enantiomerically enriched allylic carbonate I with secondary alkenyl alcohols (R)- and (S)-II followed by ring-closing metathesis (RCM) affords the cis- and trans-disubstituted cyclic ethers III and IV, respectively (Scheme 1; n = 0-3).[5-7] The inherent advantage of this approach is the ability to vary both ring size and relative configuration as a direct function of the alkenyl alcohol nucleophile employed in the cross-coupling reaction.[8] This strategy was then applied to the total synthesis of the natural product gaur acid to establish its absolute configuration.[9,10]

Scheme 1.

General approach for the stereodivergent construction of cyclic ethers. LG=leaving group.

Table 1 outlines the development of the stereospecific allylic etherification by using the secondary copper(I) alk-oxides derived from (R)-2 (n = 1). Although we had demonstrated previously that primary copper(I) alkoxides derived from copper(I) chloride facilitate the enantiospecific etherification, the allylic etherification with the secondary copper(I) alkoxide proved problematic irrespective of the copper(I) halide employed (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).[3] Hence, we decided to screen a variety of rhodium catalysts with the expectation that the stereospecificity could be improved by either a decrease in the rate of π—σ—π isomerization or an increase in the rate of nucleophilic attack.

Table 1.

Optimization of the rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification with the copper(I) alkenyl alkoxide derived from (R)-2 (n=1).[a]

| Entry | Catalyst | Additive | 3/4[b],[c] | d.r.3a/3b[b] | Yield[%][d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [RhCl(PPh3)3]/P(OMe)3 | CuCl | 9:1 | 2:1 | 20 |

| 2 | [RhCl(PPh3)3]/P(OMe)3 | CuI | 11:1 | 4:1 | 63 |

| 3 | [{RhCl(C2H4)2]/P(OMe)3 | CuI | 13:1 | 3:1 | 63 |

| 4 | [RhCl(PPh3)3]/P(OMe)3 | CuI/PPh3 | 13:1 | 7:1 | 46 |

| 5 | [RhCl(PPh3)3]/P(OMe)3 | CuI/P(OMe)3 | 49:1 | ≥99:1 | 72 |

| 6 | [RhCl(PPh3)3] | CuI/P(OMe)3 | 24:1 | 10:1 | 15 |

All reactions (0.25 mmol) were carried out with 10 mol% of the catalyst in tetrahydrofuran with 1.9 equivalents of the copper alkoxide.

Diastereomeric ratios were determined by capillary GLC on aliquots of the crude reaction mixture.

Authentic standards were prepared independently by using copper cyanide as an additive.

Yields of the isolated products. Bn=benzyl, HMDS=hexamethyldisilazide, PMP=p-methoxyphenyl, RT=room temperature.

Preliminary screening of the catalyst derived from μ-dichlorotetraethylene dirhodium(I), in which there is no free triphenylphosphane from the in situ ligand exchange, with trimethylphosphite demonstrated slightly diminished stereospecificity. This result was intriguing given that the same catalyst is presumably formed through its in situ modification as that formed with the Wilkinson catalyst.[11] We reasoned that the difference could be attributed to the absence of residual triphenylphosphane from the in situ ligand exchange in the latter case; the triphenylphosphane presumably modifies and thereby activates the copper(I) alkoxide. To test this hypothesis, the copper(I) alkoxide derived from (R)-2 (n = 1) was treated with an equimolar amount of triphenylphosphane, with the expectation that this would improve the stereospecificity. Gratifyingly, an increase in the specificity was observed (Table 1, entry 4), which prompted the screening of additional ligands. This study demonstrated trimethylphosphite to be the optimal ligand in terms of the regioselectivity and enantiospecificity of the catalyst (Table 1, entry 5). Thus, it appears that the phosphite ligand activates the copper(I) alkoxide so that it alkylates the rhodium—allyl electrophile stereospecifically prior to π—σ—π isomerization. To rule out the possibility that the rhodium catalyst is further modified with the additional trimethylphosphite, the reaction was performed with the phosphite-ligated copper(I) alkoxides in the presence of an unmodified Wilkinson catalyst (Table 1, entry 6). This led to poor turnover and modest stereospecificity, thus indicating minimal transfer of trimethylphosphite from the copper(I) alkoxide to the rhodium catalyst.

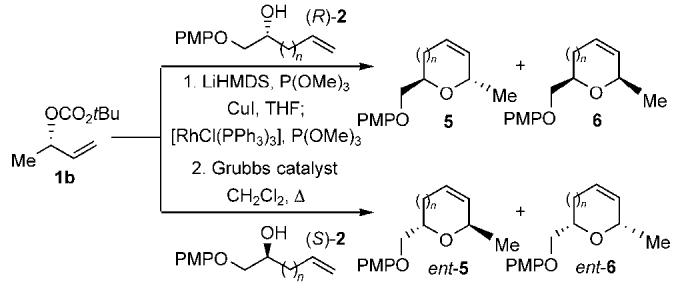

The rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification with the copper(I) alkoxide derived from the alkenyl alcohols (R) and (S)-2 was studied in combination with subsequent ring-closing metathesis to furnish the cis- and trans-disubstituted cyclic ethers 5 and ent-6 (Table 2).[5-7] This study demonstrates that excellent regioselectivity and enantiospecificity is observed irrespective of which enantiomer of the alkenyl copper(I) alkoxide is employed (Table 2, entries 1-8). Moreover, ring-closing metathesis with the Grubbs catalyst proceeds to furnish the cyclic ethers in good to excellent yield. However, the construction of the oxocine 5d and ent-6d required the use of the Grubbs N-heterocyclic carbene catalyst and very high dilution for efficient cyclization (Table 2, entries 7-8). Overall, the ability to form cyclic ethers in this manner is impressive not only in terms of the excellent stereospecificity, but also because of the minimal conformational bias present for the formation of medium-ring ethers.[12]

Table 2.

Scope of the rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification with the copper(I) alkenyl alkoxides 2 followed by ring-closing metathesis.[a],[b]

| Entry | Config. of 2 | n | d.r.[c] | Yield of addition product [%][d] | Cyclic ether | Yield [%][d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R | 0 | 53:1 | 74 | 5a | 94 |

| 2 | S | 0 | 1:50 | 78 | ent-6a | 99 |

| 3 | R | 1 | 23:1 | 77 | 5b | 85 |

| 4 | S | 1 | 1:23 | 76 | ent-6b | 98 |

| 5 | R | 2 | 27:1 | 77 | 5c | 85 |

| 6 | S | 2 | 1:26 | 77 | ent-6c | 93 |

| 7 | R | 3 | 29:1 | 77 | 5d | 73[e] |

| 8 | S | 3 | 1:39 | 77 | ent-6d | 82[e] |

All allylic etherification reactions (0.25 mmol) were carried out with 10 mol% of the catalyst in tetrahydrofuran with 1.9 equivalents of the copper alkoxide. The regioselectivity (2°/1°) observed for the addition of the copper alkoxide was ≥99:1 in all cases. (Authentic standards were prepared independently by using copper cyanide as an additive.)

All ring-closing metathesis reactions were carried out on a 0.1-mmol scale with 5-10 mol% of the Grubbs catalyst in dichloromethane (0.1M).

Ratios of regio- and diastereoisomers were determined by capillary GLC on aliquots of the crude reaction mixture.

Yields of the isolated products.

The Grubbs N-heterocyclic carbene catalyst (0.001M) was used at reflux.

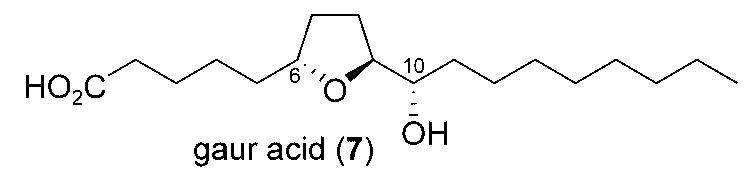

Gaur acid (7) was recently isolated from the oily secretion of the gaur (B. frontalis), a wild ox in Asia, by Oliver et al.[9,10] This 18-carbon acid is thought to serve as a landing and feeding deterrent for the yellow-fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti). Although the relative configuration of 7 was assigned, the absolute configuration of this agent had not been established. We envisaged that the rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification in conjunction with ring-closing metathesis would provide a stereospecific route to the trans-2,5-disubstituted tetrahydrofuran present in this potentially biologically important agent, and thereby enable the determination of the absolute configuration.

|

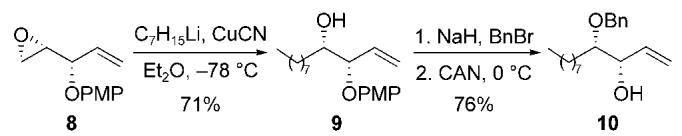

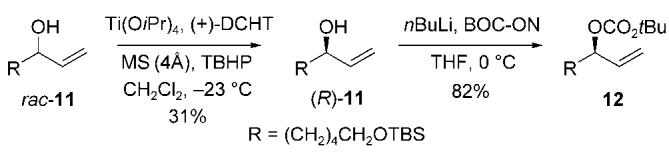

The allylic alcohol 10 was prepared by the three-step sequence outlined in Scheme 2. Regioselective ring-opening of the known epoxide 8 with the cuprate derived from n-heptyllithium and copper(I) cyanide at -78°C, gave the desired alcohol 9 in 71 % yield.[13,14] Benzyl protection of the secondary alcohol 9, followed by oxidative cleavage of the p-methoxyphenyl group, furnished the allylic alcohol 10 in 76 % yield (two steps).[15] The enantiomerically enriched allylic carbonate 12 was prepared by an initial Sharpless kinetic resolution of the allylic alcohol rac-11, followed by acylation of the product (R)-11 (≥ 99 % ee) with BOC-ON (Scheme 3).[16]

Scheme 2.

Preparation of the enantiomerically enriched allylic alcohol nucleophile. CAN=cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of the enantiomerically enriched allylic carbonate electrophile. BOC-ON=2-(tert-butoxycarbonyloxyimino)-2-phenylacetonitrile, DCHT=dicyclohexyl tartrate, MS=molecular sieves, TBHP=tert-butyl hydroperoxide, TBS=tert-butyldimethylsilyl.

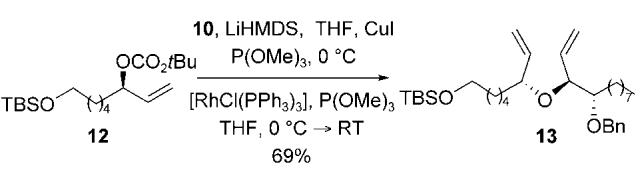

The stereospecific allylic etherification was carried out under analogous reaction conditions to those outlined in Table 2.[17] Treatment of the allylic carbonate 12 with the trimethylphosphite-modified Wilkinson catalyst and the copper(I) alkoxide derived from the allylic alcohol 10, afforded the diene 13 in 69 % yield with excellent regioselectivity and enantiospecificity [≥ 19:1 by NMR spectroscopy, Eq. (1)].

|

(1) |

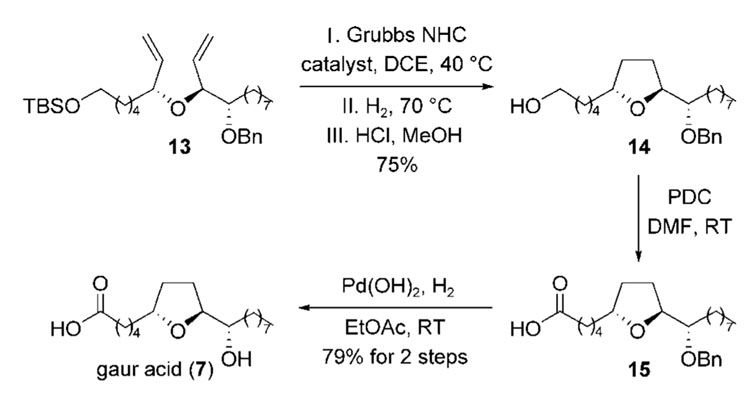

The synthesis of gaur acid (7) was then completed as illustrated in Scheme 4. Treatment of the diene 13 with the Grubbs N-heterocyclic carbene catalyst at 40°C gave the desired cyclic ether, which was reduced in situ and deprotected with acid to afford the primary alcohol 14 in 75 % overall yield.[18] The hydrogenation of the alkene in the metathesis product was necessary at this juncture because of its propensity to undergo oxidation. Oxidation of the primary alcohol 14 by pyridinium dichromate,[19] followed by palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation of the benzyl ether, furnished gaur acid (7) in 79 % yield (two steps). Although the spectroscopic data of the synthetic sample of 7 is identical in all respects to those of the natural substance (1H/13C NMR, IR, and MS), the optical rotation has the opposite sign (; lit.:[9,10] ), thus indicating the absolute configuration of the natural product to be 6S, 9R, 10R.[20]

Scheme 4.

Completion of the synthesis of gaur acid (7). DCE=1,2-dichloroethane, DMF=N,N-dimethylformamide, NHC=N-heterocyclic carbene, PDC=pyridinium dichromate.

In conclusion, the stereospecific rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification with secondary alkenyl alcohols in conjunction with ring-closing metathesis provides a direct approach to cis-and trans-disubstituted cyclic ethers. This study demonstrated that a dramatic enhancement of the stereospecificity is possible through the modification of the copper(I) alkoxide with trimethylphosphite, which presumably promotes the rapid nucleophilic attack of the rhodium—allyl intermediate prior to the π—σ—π isomerization. Finally, the potential of this methodology was highlighted through a seven-step total synthesis of gaur acid (7), whereby the absolute configuration of 7 was established.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We sincerely thank the National Institutes of Health (GM58877) for generous financial support. We also thank Johnson and Johnson for a Focused Giving Award, Pfizer GRD for the Creativity in Organic Chemistry Award, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences for a JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (D.U.). We acknowledge Dr. James E. Oliver, who also recently completed a total synthesis of gaur acid, for providing spectroscopic and optical-rotation data for this compound.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1]. For recent reviews on metal-catalyzed allylic substitution, see:; a) Tsuji J. Palladium Reagents and Catalysts. Wiley; New York: 1996. pp. 290–404. [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Lee C.Ojima I.Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis 2000593–649.Wiley-VCH; New York: 2nd ed.and references therein [Google Scholar]

- [2]. For related references on intermolecular metal-catalyzed allylic etherification reactions with metal alkoxides, see:; a) Keinan E, Sahai M, Roth Z, Nudelman A, Herzig J. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:3558–3566. [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Tenaglia A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:2931–2934. [Google Scholar]; c) Trost BM, McEachern EJ, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12702–12703. [Google Scholar]; d) Kim H, Lee C.Org. Lett 200244369–4371.and references therein [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Evans PA, Leahy DK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7882–7883. doi: 10.1021/ja026337d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Whitesides GM, Sadowski JS, Lilburn J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:2829–2835. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. For recent reviews on ring-closing metathesis, see:; a) Grubbs RH, Chang S. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4413–4450. [Google Scholar]; b) Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:3140–3172. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3012–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Deiters A, Martin SF.Chem. Rev 20041042199–2238.and references therein [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fu GC, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5426–5427. [Google Scholar]

- [7]. For recent examples of the synthesis of cyclic ethers by ring-closing metathesis, see:; a) Heck M-P, Baylon C, Nolan SP, Mioskowski C. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1989–1991. doi: 10.1021/ol0159625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nicolaou KC, Vega JA, Vassilikogiannakis G. Angew. Chem. 2001;113:4573–4577. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4441::aid-anie4441>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4441–4445. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4441::aid-anie4441>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Fujiwara K, Souma S-I, Mishima H, Murai A. Synlett. 2002:1493–1495. [Google Scholar]; d) Sutton AE, Seigal BA, Finnegan DF, Snapper ML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13390–13391. doi: 10.1021/ja028044q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Peczuh MW, Snyder N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4057–4061. [Google Scholar]; f) Crimmins MT, Powell MT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7592–7595. doi: 10.1021/ja029956v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. For an explanation of the effect of copper(I) halide salts on the stereospecificity of the rhodium-catalyzed allylic etherification reaction with copper(I) alkoxides, see:; Evans PA, Leahy DK, Slieker LM. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:3613–3618. [Google Scholar]

- [9]. For the isolation of the same agent from sheep wool, see:; Ito S, Endo K, Inoue S, Nozoe T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971:4011–4014. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Oliver JE, Weldon PJ, Peterson KS, Schmidt WF, Debboun M. Abstracts of Papers. 225th ACS National Meeting; New Orleans, LA, USA. March 23-27, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Wu ML, Desmond MJ, Drago RS. Inorg. Chem. 1979;18:679–686. [Google Scholar]; b) Watson LA, Leahy DK, Evans PA, Caulton KG.

- [12].a) Clark JS, Kettle JG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:127–130. [Google Scholar]; b) Linderman RJ, Siedlecki J, O'Neill SA, Sun H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6919–6920. [Google Scholar]; c) Crimmins MT, Choy AL. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7548–7549. doi: 10.1021/jo9716688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schreiber SL, Schreiber TS, Smith DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:1525–1529. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Evans PA, Cui J, Gharpure SJ, Polosukhin A, Zhang H-R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14702–14703. doi: 10.1021/ja0384734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fukuyama T, Laird AA, Hotchkiss LM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:6291–6292. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547. [Google Scholar]

- [17].This rather demanding cross-coupling reaction required a higher catalyst loading (30 mol %) for efficient and complete conversion

- [18].Louie J, Bielawski CW, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11312–11313. doi: 10.1021/ja016431e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Corey EJ, Schmidt G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:399–402. [Google Scholar]

- [20].This result contradicts the original stereochemical assignment made by Ito et al. for the same agent isolated from sheep wool, by analogy with a C16 derivative.[9]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.