Abstract

This guideline has been discussed by the SOSORT guideline committee prior to the SOSORT consensus meeting in Milan, January 2005 and published in its first version on the SOSORT homepage: http://www.sosort.org/meetings.php. After the meeting it again has been discussed by the members of the SOSORT guideline committee to establish the final 2005 version submitted to Scoliosis, the official Journal of the society, in December 2005.

Definition

Scoliosis is defined as a lateral curvature of the spine with torsion of the spine and chest as well as a disturbance of the sagittal profile [2].

Etiology

Idiopathic scoliosis is the most common of all forms of lateral deviation of the spine. By definition, it is a lateral curvature of the spine in an otherwise healthy child, for which a currently recognizable cause has not been found. Less common but better defined etiologies of the disorder include scoliosis of neuromuscular origin, congenital scoliosis, scoliosis in neurofibromatosis, and mesenchymal disorders like Marfan's syndrome [3].

Epidemiology

The prevalence of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), when defined as a curvature greater than 10° according to Cobb, is 2–3%. The prevalence of curvatures greater than 20° is between 0.3 and 0.5%, while curvatures greater than 40° Cobb are found in less than 0.1% of the population. All etiologies of scoliosis other than AIS are encountered more rarely [4].

Classifications

The anatomical level of the deformity has received attention from clinicians as a basis for scoliosis classification. The level of the apex vertebra (i.e., thoracic, thoracolumbar, lumbar or double major) forms a simple basis for description. In 1983, King and colleagues [5] classified different curvature patterns by the extent of spinal fusion required; however, recent reports have suggested that these classifications lack reliability. Recently, a new description has been developed by Lenke and colleagues [6]. This approach calls for clinical assessment of scoliosis and kyphosis with respect to sagittal profile and curvature components. Systems designed for conservative management include the classifications by Lehnert-Schroth [7] (functional three-curve and functional four-curve scoliosis) and by Rigo [8] (brace construction and application).

Aims of conservative management

The primary aim of scoliosis management is to stop curvature progression [9]. Improvement of pulmonary function (vital capacity) and treatment of pain are also of major importance. The first of three modes of conservative scoliosis management is based on physical therapy, including Méthode Lyonaise [10], Side-Shift [11], Dobosiewicz [12], Schroth and others [7]. Although discussed from contrasting viewpoints in the international literature, there is some evidence for the effectiveness of scoliosis treatment by physical therapy alone [13].

It has to be emphasized that (1) physical therapy for scoliosis is not just general exercises but rather one of the cited methods designed to address the particular nuances of spinal deformity, and (2) application of such methods requires therapists and clinicians specifically trained and certified in those scoliosis specific conservative intervention methods.

The second mode of conservative management is scoliosis intensive rehabilitation (SIR), which appears to be effective with respect to many signs and symptoms of scoliosis and with respect to impeding curvature progression [14]. The third mode of conservative management is brace treatment, which has been found to be effective in preventing curvature progression and thus in altering the natural history of IS [15,16]. It appears that brace treatment may reduce the prevalence of surgery [17], restore the sagittal profile [18] and influence vertebral rotation [19]. There are also indications that the end result of brace treatment can be predicted [20].

Systematic application of the modes of conservative treatment with respect to Cobb angle and maturity

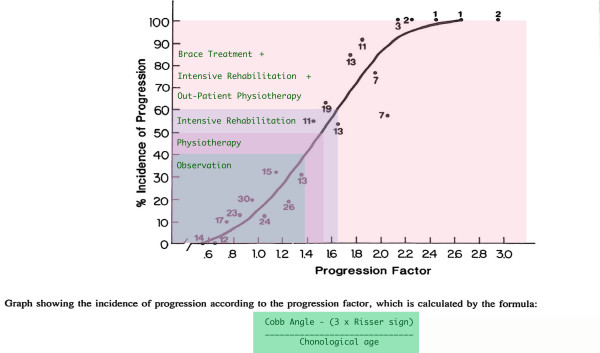

Guidelines for conservative intervention are based on current information regarding the risk for significant curvature progression in a given period of time. Each case has its own natural history and must be considered on an individual basis, in the context of a thorough clinical evaluation and patient history [21]. Estimation of risk for progression is based on small (n < 1000) epidemiological surveys in which children were diagnosed with scoliosis, and radiographed periodically to quantify changes in curvature magnitude over time [22-44]. Such surveys support the premise that, among populations of children with a diagnosis of idiopathic scoliosis, risk for progression is highly correlated with potential for growth over the period of observation. In boys, prognosis for progression is more favorable, with relatively fewer individuals having curves that progress to >40 degrees. For SOSORT guidelines, prognostic risk estimation is based on the calculation of Lonstein and Carlson [33]. This calculation is based on curvature progression observed among 727 patients (575 female, 152 male) diagnosed between 1974–1979 in state of Minnesota (United States) school screening programs, and followed until they reached skeletal maturity. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The estimation of the prognostic risk to be used during pubertal growth spurt (modified from Lonstein and Carlson [33]). The numbers in the figure indicate the number of cases that each data point is based on. Note the small number of cases on which the upper margins of the graph are based. Lonstein and Carlson's progression estimation formula is based on curves between 20 and 29 degrees.

I. Children (no signs of maturity) [21]

a. < 15° Cobb: Observation (6 – 12 month intervals)

b. Cobb angle 15–20°: Outpatient physical therapy with treatment-free intervals (6–12 weeks without physical therapy for those patients at that time have low risk for curve progression). In this context, 'Outpatient physical therapy' is defined here as exercise sessions initiated at the physical therapist's office, plus a home exercise program (two to seven sessions per week according to the physical therapy method being applied). After three months, one exercise session every two weeks may be sufficient.

c. Cobb angle 20–25°: Out patient physiotherapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available.). SIR, currently available at clinics in Germany and Spain, includes a 3- to 5- week intensive program (4 – 6 hour training sessions per day) for patients with poor prognosis (brace indication, adult with Cobb angle of > 40°, presence of chronic pain).

d. > 25° Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available and brace wear (part-time, 12–16 hours)

II. Children and adolescents, Risser 0–3, first signs of maturation, less than 98% of mature height

The following section is based on progression risk rather than on Cobb angle measurement because of the changing risk profiles for deformityas theskeleton matures. For our purposes, progression risk is calculated by the formula shown in figure 1.

a. Progression risk less than 40%: Observation (3-month intervals)

b. Progression risk 40%: Out patient physiotherapy

c. Progression risk 50%: Out patient physiotherapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available

d. Progression risk 60%: Out patient physiotherapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available + part-time brace indication (16 – 23 hours [low risk]).

e. Progression risk 80%: Out patient physiotherapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available + full-time brace indication (23 hours [high risk])

III. Children and adolescents presenting with Risser 4 (more than 98% of mature height)

a. < 20° according to Cobb: Observation (6 – 12 Months intervals)

b. 20 – 25° according to Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy

c. > 25° according to Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation programme (SIR) where available

d. > 35° according to Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation programme (SIR) where available + brace (part time, about 16 hours are sufficient)

e. For brace weaning: Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation programme (SIR) where available + brace with reduced wearing time.

IV. First presentation with Risser 4–5 (more than 99.5% of mature height before growth is completed)

a. > 25° Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy

b. > 30° Cobb: Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available.

V. Adults with Cobb angles > 30°

Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR), where available

VI. Adolescents and adults with scoliosis (of any degree) and chronic pain

Outpatient physical therapy, scoliosis intensive rehabilitation program (SIR) where available, with a special pain program (multimodal pain concept/behavioral + physical concept), brace treatment when a positive effect has been proven [45].

The prognostic estimation and corresponding indications for treatment apply to the most prevalent condition, idiopathic scoliosis. In other types of scoliosis a similar procedure can be applied. Exceptions include those cases where the prognosis is clearly worse, for example in neuromuscular scolioses where a wheelchair is necessary (early surgery for maintaining sitting capability may be required). Other reasons for the consideration of alternative treatments include:

- Severe decompensation

- Severe sagittal deviations with structural lumbar kyphosis ('flatback')

- Lumbar, thoracolumbar and caudal component of double curvatures with a disproportionate rotation compared to the Cobb angle and with high risk for future instability at the caudal junctional zone

- Severe contractures and muscles shortening

- Reduced mobility of the spine especially in the sagittal plane

- others to be individually considered [46]

Authors' contributions

*These authors contributed by reviewing, text editing and adding certain textfiles and references

Contributor Information

SOSORT guideline committee, Email: hr.weiss@asklepios.com.

Hans-Rudolf Weiss, Email: hr.weiss@asklepios.com.

Stefano Negrini, Email: stefano.negrini@isico.it.

Manuel Rigo, Email: lolo_rigo@hotmail.com.

Tomasz Kotwicki, Email: tomaszkotwicki@poczta.onet.pl.

Martha C Hawes, Email: mhawes@u.arizona.edu.

Theodoros B Grivas, Email: grivastb@panafonet.gr.

Toru Maruyama, Email: tmaruyama17@ybb.ne.jp.

Franz Landauer, Email: f.landauer@SALK.AT.

References

- http://www.sosort.org/meetings.php

- Stokes IAF. Die Biomechanik des Rumpfes. In: Weiss HR, editor. Wirbelsäulendeformitäten – Konservatives Management. München, Pflaum; 2003. pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Winter RB. Moe's Textbook of Scoliosis and Other Spinal Deformities. 2. Philadelphia Saunders; 1995. Classification and Terminology; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SL. Natural history. Spine. 1999;24:2592–2600. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King HA, Moe JHY, Bradford DS, Winter RB. The selection of fusion levels in thoracic IS. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1983;65-A:1302–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield PH. Klassifikation von Wirbelsäulendeformitäten. In: Weiss HR, editor. Wirbelsäulendeformitäten – Konservatives Management. München, Pflaum; 2003. pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert-Schroth C. Dreidimensionale Skoliosebehandlung. 6. Urban/Fischer, München; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rigo M. Intraobserver reliability of a new classification correlating with brace treatment. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2004;7:63. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001654736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer F, Wimmer C. Therapieziel der Korsettbehandlung bei idiopathischer Adoleszentenskoliose. MOT. 2003;123:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mollon G, Rodot JC. Scolioses structurales mineures and kinesitherapie. Etude statistique comparative des resultats. Kinesitherapie Scientifique. 1986;244:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta MH. Active auto-correction for early AIS. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1986;68:682. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HR, Negrini S, Hawes MC, Rigo M, Kotwicki T, Grivas TB, Maruyama and members of the SOSORT Physical Exercises in the Treatment of Idiopathic Scoliosis at Risk of brace treatment – SOSORT Consensus paper 2005. Scoliosis. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Negrini S, Antoninni GI, Carabalona R, Minozzi S. Physical exercises as a treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A systematic review. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6:227–235. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001636781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HR, Weiss G, Petermann F. Incidence of curvature progression in idiopathic scoliosis patients treated with scoliosis in-patient rehabilitation (SIR): an age- and sex-matched cotrolled study. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6:23–30. doi: 10.1080/1363849031000095288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachemson AL, Peterson LE, Members of Brace Study Group of the Scoliosis Research Society Effectiveness of treatment with a brace in girls who have adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77:815–822. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivas TB, Vasiliadis E, Chatziargiropoulos T, Polyzois VD, Gatos K. The effect of a modified Boston brace with anti-rotatory blades on the progression of curves in idiopathic scoliosis: aetiologic implications. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6:237–242. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001636808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo M, Reiter C, Weiss HR. Effect of conservative management on the prevalence of surgery in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6:209–214. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001642054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo M. 3 D Correction of Trunk Deformity in Patients with Idiopathic Scoliosis Using Chêneau Brace. In: Stokes IAF, editor. Research into Spinal Deformities 2 Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 1999. pp. 362–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kotwicki T, Pietrzak S, Szulc A. Three-dimensional action of Cheneau brace on thoracolumbar scoliosis. In: Tanguy A, Peuchot B, editor. Research into Spinal Deformities 3 Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2002. pp. 226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer F, Wimmer C, Behensky H. Estimating the final outcome of brace treatment for idiopathic thoracic scoliosis at 6-month follow-up. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6:201–207. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001636817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JE. Moe's Textbook of Scoliosis and Other Spinal Deformities. 2. Philadelphia, Saunders; 1995. Patient Evaluation; pp. 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ascani E, Bartolozzi P, Logroscino CA, Marchetti PG, Ponte A, Savini R, Travaglini F, Binazzi F, Di Silvestre M. Natural history of untreated IS after skeletal maturity. Spine. 1986;11:784–789. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkreim R, Hassan I. Progression in untreated IS after the end of growth. Acta orthop scand. 1982;53:897–900. doi: 10.3109/17453678208992845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks HL, Azen SP, Gerberg E, Brooks R, Chan L. Scoliosis: a prospective epidemiological study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1975;57:968–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell WP. The natural history of IS before skeletal maturity. Spine. 1986;11:773–776. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarisse P. Thesis. Lyon France; 1974. Pronostic evolutif des scolioses idiopathiques mineures de 10–29 degrees, en periode de croissance. [Google Scholar]

- Collis DK, Ponseti IV. Long-term followup of patients with idiopathic scoliosis not treated surgically. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1969;51-A:425–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Beaupere G. Rib hump and supine angle as prognostic factors for mild scoliosis. Spine. 1992;17:103–107. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Beaupere G. Threshold values for supine and standing Cobb angles and rib hump measurements: prognostic factors for scoliosis. European Spine Journal. 1996;5:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00298385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karol LA, Johnston CE, Browne RH, Madison M. Progression of the curve in boys who have IS. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1993;75:1804–1810. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindsfater K, Lowe T, Lawellin D, Weinstein D, Akmakjian A. Levels of platelet calmodulin for the prediction of progression and severity of AIS. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1994;76-A:1186–1192. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korovessis P, Piperos G, Sidiropoulos P, Dimas A. Adult idiopathic lumbar scoliosis: a formula for prediction of progression and review of the literature. Spine. 1994;19:1926–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JE, Carlson JM. The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1984;66-A:1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masso PD, Meeropol E, Lennon E. Juvenile onset scoliosis followed up to adulthood: orthopedic and functional outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2002;22:279–284. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade KP, Bunch W, Vanderby R, Patwardhan AG, Knight G. Progression of unsupported curves in AIS. Spine. 1987;12:520–526. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M. The rib-vertebra angle in the early diagnosis between resolving and progressive infantile scoliosis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1972;54B:230–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachemson A. A long term followup study of nontreated scoliosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1968;39:466–476. doi: 10.3109/17453676808989664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picault C, deMauroy JC, Mouilleseaux B, Diana G. Natural history of idiopathic scoliosis in girls and boys. Spine. 1986;11:777–778. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CM, McMaster MJ, Juvenile IS. Curve patterns and prognosis in 109 patients. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1996;78-A:1140–1148. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucacas PN, Zacharis K, Loultanis K, Gelalis J, Xenakis T, Beris AE. Risk factors for IS: review of a 6-year prospective study. Orthopedics. 2000;23:833–838. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000801-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucacos PN, Zacharis K, Soultanis K, Gelalis J, Kalos N, Beris A, Xenakis T, Johnson EO. Assessment of curve progression in IS. European Spine Journal. 1998;7:270–277. doi: 10.1007/s005860050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemure I, Aubin CE, Grimard G, Dansereau J, Labelle H. Progression of vertebral and spinal 3-D deformities in AIS. A longitudinal study. Spine. 2001;26:2244–2250. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200110150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever DJ, Tonseth KA, Veldhuizen AG, Cool JC, vanHorn JR. Curve progression and spinal growth in brace treated IS. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2000;337:169–179. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y, Yamaguchi T, Asaka Y. Prediction of curve progression in IS based on initial roentgenograms; proposal of an equation. Spine. 1988;13:1258–1261. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HR. Das „Sagittal Realignment Brace" (physio-logic® brace) in der Behandlung von erwachsenen Skoliosepatienten mit chronifiziertem Rückenschmerz – erste vorläufige Ergebnisse. Medizinisch Orthopädische Technik. 2005;125:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Negrini S, Aulisa L, Ferraro C, Fraschini P, Masiero S, Simonazzi P, Tedeschi C, Venturin A. Italian guidelines on rehabilitation treatment of adolescents with scoliosis or other spinal deformities. Eura Medicophys. 2005;41:183–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]