Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare the demographic and educational characteristics of Canadian international medical graduates (IMGs) and immigrant IMGs who applied to the second iteration of the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) match in 2002.

DESIGN

Web-based questionnaire survey.

SETTING

The study was conducted during the second-iteration CaRMS match in Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

The sampling frame included the entire population of IMG registrants for the 2002 CaRMS match in Canada who expressed interest in applying for a ministry-funded residency position in the 13 English-speaking Canadian medical schools. Those who immigrated to Canada with medical degrees were categorized as immigrant IMGs. Canadian citizens and landed immigrants or permanent residents who left Canada to obtain a medical degree in another country were defined as Canadian IMGs.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Demographic characteristics, education and training outside Canada, examinations taken, previous applications for a residency position, preferred type of practice, and barriers and supports were compared.

RESULTS

Out of 446 respondents who indicated their immigration status and education, 396 (88.8%) were immigrant IMGs and 50 (11.2%) were Canadian IMGs. Immigrant IMGs tended to be older, be married, and have dependent children. Immigrant IMGs most frequently obtained their medical education in Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or Africa, whereas Canadian IMGs most frequently obtained their medical degrees in Asia, the Caribbean, or Europe. Immigrant IMGs tended to have more years of postgraduate training and clinical experience. A significantly greater proportion of immigrant IMGs had perceived that there were insufficient opportunities for assessment, financial barriers to training, and licensing barriers to practice. Nearly half (45.5%) of all IMGs selected family medicine as their first choice of clinical discipline to practise in Canada. There were no significant differences between Canadian and immigrant IMGs in terms of first choice of clinical discipline (family medicine vs specialty). There were no significant differences between the groups in the number of times they applied to CaRMS in the past, but a relatively greater proportion of Canadian IMGs obtained residency positions.

CONCLUSION

There are notable similarities and some significant differences between Canadian and immigrant IMGs seeking to practise medicine in Canada.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Comparer les caractéristiques démographiques et la formation des médecins canadiens et immigrants diplômés hors Canada (DHC) qui se sont présentés au deuxième tour du jumelage du système CaRMS (Canadian Resident Matching Service) en 2002.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Étude par questionnaire via Internet.

CONTEXTE

L’étude a eu lieu durant le second tour du jumelage CaRMS au Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Le cadre d’échantillonnage incluait tous les médecins DHC inscrits au jumelage CaRMS de 2002 au Canada qui se montraient intéressés à décrocher un poste de résidence rémunéré par le ministère dans une des 13 facultés de médecine anglophones canadiennes. Ceux qui détenaient un diplôme de médecine avant d’arriver au Canada ont été qualifiés d’immigrants DHC. Les citoyens canadiens et les immigrants reçus qui sont allés obtenir leur diplôme à l’étranger sont appelés Canadiens DHC.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

On a comparé les caractéristiques démographiques, l’instruction et la formation à l’étranger, les examens effectués, les candidatures antérieures à des postes de résidence, le type de pratique souhaité, et les obstacles et ressources éventuels.

RÉSULTATS

Sur 446 répondants qui ont indiqué leur statut d’immigrant et précisé leur formation, 396 (88%) étaient des immigrants DHC et 50 (11,2%) des Canadiens DHC. En général, les immigrants DHC étaient plus vieux, étaient mariés et avaient des enfants à charge. Ils avaient souvent été formés en Asie, en Europe de l’Est, au Moyen-Orient ou en Afrique, tandis que les Canadiens DHC avaient fréquemment fait leurs études médicales en Asie, dans les Caraïbes ou en Europe. Dans l’ensemble, les immigrants DHC avaient plus d’années de formation post-md et une plus longue expérience clinique. Une proportion significativement plus grande d’immigrants DHC avaient eu l’impression qu’il n’y avait pas assez de possibilités d’évaluation, qu’il y avait des obstacles financiers à la formation et certaines difficultés pour obtenir le permis de pratique. Près de la moitié (45,5%) de tous les DHC avaient choisi la médecine familiale comme premier champ de pratique au Canada. Il n’y avait pas de différence significative entre les deux groupes pour ce qui est du champ de pratique choisi en premier (médecine familiale vs spécialité). Il n’y en avait pas non plus pour le nombre d’inscriptions antérieures au CaRMS; toutefois, une proportion relativement plus grande de Canadiens DHC avaient obtenus des postes de résidence.

CONCLUSION

Il y a des similitudes remarquables et quelques différences importantes entre les Canadiens et les immigrants DHC qui désirent pratiquer la médecine au Canada.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

International medical graduates (IMGs) in Canada are either immigrants from other countries or Canadians who obtained their MD degrees abroad. Both groups must apply to the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) for postgraduate training.

In 2002, approximately 650 IMGs applied to CaRMS. In this survey (70% response rate), 89% were immigrant IMGs and 11% were Canadians.

Immigrant IMGs were older, had more postgraduate experience, and were more likely to be married and have children than Canadian IMGs.

Forty-five percent of both immigrant and Canadian IMGs chose family medicine compared with 30% of Canadian medical school graduates. Only 11% of immigrant IMGs were accepted for any residency; 34% of Canadians were accepted into residency.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Au Canada, les médecins diplômés hors Canada (DHC) sont des immigrants d’autres pays ou des Canadiens qui ont obtenu leur diplôme de médecine à l’étranger. Ces deux groupes doivent se présenter au jumelage du système CaRMS pour obtenir des postes de résidence.

En 2002, environ 650 DHC se sont présentés au CaRMS. Dans cette étude (taux de réponse de 70%), 89% des DHC étaient des immigrants et 11% des Canadiens.

Par rapport aux Canadiens DHC, les immigrants étaient plus âgés, avaient une plus longue expérience post-md et étaient plus susceptibles d’être mariés et d’avoir des enfants.

Les Canadiens et les immigrants DHC ont choisi la médecine familiale dans une proportion de 45% comparativement à 30% pour les diplômés des facultés de médecine canadiennes. Seulement 11% des DHC immigrants ont obtenu un poste de résidence contre 34% pour des DHC canadiens.

In Canada, the term international medical graduates (IMGs) is used collectively to refer to several types of medical school graduates. It includes Canadian citizens and permanent residents who have gone abroad for their medical education, as well as immigrants to Canada with medical degrees from other countries.

Some IMGs must complete postgraduate residency training in Canada before they can be licensed to practise medicine. Each year, many IMGs apply for residency training through the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS), a national organization that matches eligible applicants to ministry-funded postgraduate residency positions in the 13 English-speaking Canadian medical schools.

The number of IMGs applying through CaRMS has been steadily increasing, from 240 in 1995 to 657 in 2004.1 During the 2002, 2003, and 2004 CaRMS matches, IMGs accounted for 10.2%, 10%, and 12.4%, respectively, of the total residency positions filled in family medicine and 4.7%, 2.4%, and 2.9%, respectively, of residency positions filled in all the specialty disciplines combined.2-4 During the same period, 75.8%, 40.5%, and 66.7% of vacant residency positions in family medicine and 52.9%, 44.4%, and 48.1% of vacant specialty positions were filled by IMGs during the second-iteration match.2-4 Consequently, IMGs are having a substantial effect on family medicine residency programs across Canada.

Little is known about the various groups of IMGs who seek postgraduate residency training in Canada. A better understanding of the various IMG subgroups could lead to better alignment of IMGs’ and Canadian health system needs. Knowledge of the education and previous experience of IMGs would help us modify postgraduate training programs in family medicine to meet the specific needs of IMGs who hope to practise in Canada. The published literature lacks comparative data on Canadian and immigrant IMGs. A study of IMGs who applied to the 2002 CaRMS match enabled us to compare the demographic and educational characteristics of Canadian IMGs and immigrant IMGs.

METHODS

A Web-based survey was conducted via questionnaire to develop a demographic and educational profile of IMGs who were registered in the second iteration of the 2002 CaRMS match.5 For its purposes, CaRMS defines IMGs as graduates of a World Health Organization–listed medical school, and not from a Canada- or US-accredited medical school.6 The CaRMS match occurs in two iterations. The first iteration is restricted to Canadian medical school graduates who graduated in the year of the match. The second iteration is open to all applicants who did not match in the first iteration, graduates from previous years, and eligible IMGs.

The sampling frame included the entire population of IMG registrants for the 2002 CaRMS match who expressed interest in applying for ministry-funded residency positions in the 13 English-speaking Canadian medical schools (French-speaking medical schools in Quebec do not participate in the CaRMS match). International medical graduate applicants were invited to participate in the survey via a notice on the CaRMS website. The survey was conducted during the 4 weeks immediately before the 2002 CaRMS match. Access to the Web-based questionnaire was via the applicant’s CaRMS identification number. To maintain confidentiality, the CaRMS identification number was removed and replaced with an arbitrary number before data were released to investigators. To eliminate any perception that applicants’ responses jeopardized their opportunities through the match, the data were released to investigators after results of the second-iteration match were announced.

The paper-based version of the questionnaire was pilot-tested on a group of four IMGs enrolled in the Alberta IMG program. The survey included questions on demographic characteristics; undergraduate medical education and postgraduate training; type of practice desired in Canada; attempts to obtain a medical licence and residency position in Canada; perceived barriers; and opportunities for assessment, training, and practice.

We used data on immigration and education to assign IMGs to two groups. Those who immigrated to Canada with medical degrees were categorized as immigrant IMGs. Canadian citizens and landed immigrants or permanent residents who left Canada to obtain medical degrees in other countries were defined as Canadian IMGs. Demographic characteristics, education and training outside Canada, examinations taken, previous applications for a residency position, preferred practice, and barriers and supports were compared between the two groups of IMGs.

Data analysis was primarily descriptive, with frequency distributions and percentages. Chi-square and the Fisher exact test were used to examine differences between groups on selected categorical variables, as appropriate. An alpha level of .01 was used to test for statistical significance.

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Alberta and the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary.

RESULTS

Of 659 IMG registrants for the 2002 CaRMS match who were eligible to participate in the Web-based survey, 463 (70.3%) responded. The 446 (96.3%) respondents who indicated their immigration status and education were included in this comparative analysis. Of these, 396 (88.8%) were immigrant IMGs and 50 (11.2%) were Canadian IMGs.

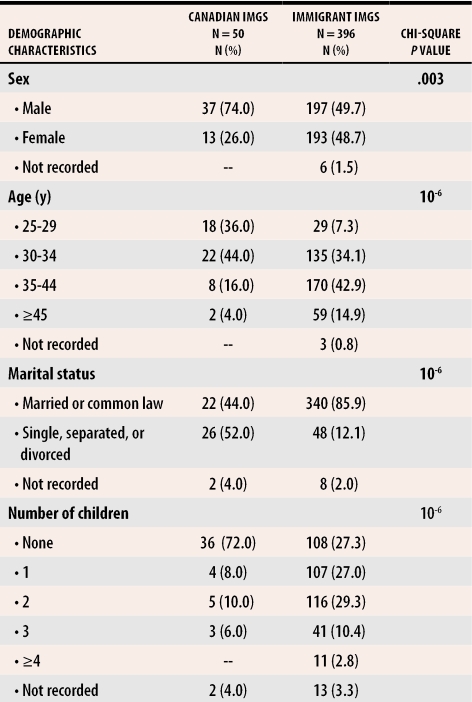

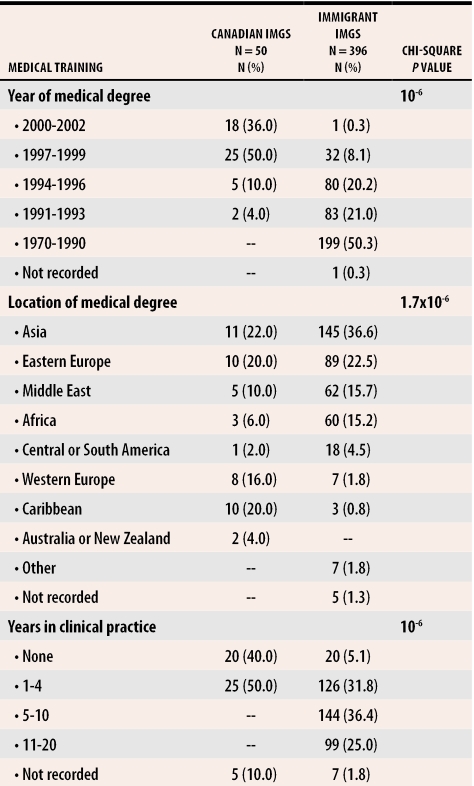

Canadian IMGs were predominantly male, between 25 and 34 years old, and single with no children. Immigrant IMGs tended to be older, to be married, and to have dependent children (Table 1). While 86% of Canadian IMGs obtained their medical degrees between 1997 and 2000, only 8.3% of immigrant IMGs did so in the same period (Table 2). Half (50.5%) of immigrant IMGs graduated before or during 1990. Immigrant IMGs most frequently obtained their medical education in Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or Africa. Canadian IMGs most frequently obtained their medical degrees in Asia, the Caribbean, or Europe. A significantly greater proportion of Canadian IMGs received their medical degrees from Caribbean (P = 3.3 x 10-8) or Western European (P = 5.5 x 10-5) countries. Whereas 84% of Canadian IMGs completed their medical training in English, only 50% of immigrant IMGs did so. More immigrant IMGs than Canadian IMGs completed rotating internships (89.9% vs 60%) or postgraduate training (75% vs 30%), respectively. Of 297 immigrant IMGs who indicated the medical discipline of the highest qualification obtained outside of Canada, 216 (72.7%) were in various specialties (primarily in surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or internal medicine) and 81 (27.3%) were in family medicine. In contrast, 10 of 15 (66.7%) Canadian IMGs completed family medicine or general practice training outside Canada.

Table 1.

Characteristics of IMG groups

Table 2.

Medical training of IMG groups

The average number of years of clinical practice was 7.3 for immigrant IMGs and 1 for Canadian IMGs (Table 2). A substantially greater proportion of Canadian IMGs had no clinical practice experience beyond their medical degree.

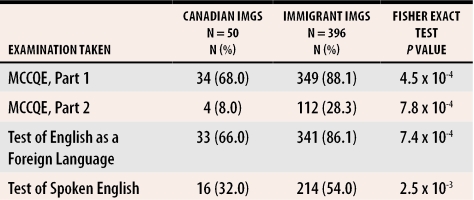

Overall, a significantly greater proportion of immigrant IMGs had taken the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination (MCCQE), Part 1 and Part 2; Test of English as a Foreign Language; and Test of Spoken English examinations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Examinations taken by respondents

MCCQE—Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination.

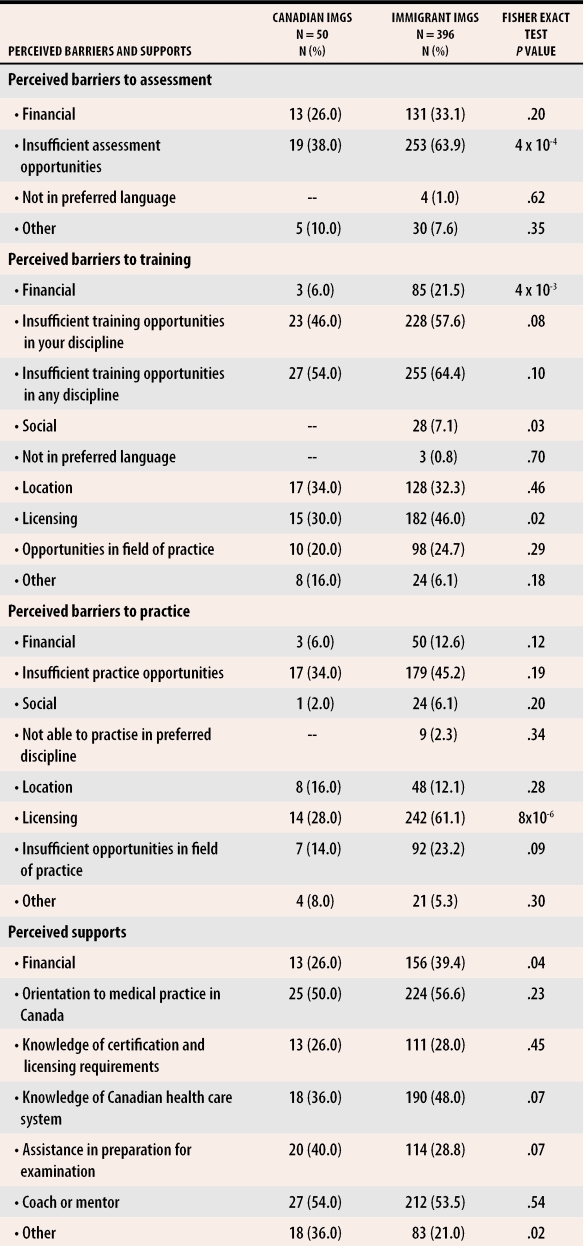

A significantly greater proportion of immigrant IMGs had perceived that there were insufficient opportunities for assessment, financial barriers to training, and licensing barriers to practice (Table 4). Overall, the top two supports all IMGs identified as being helpful were orientation to medical practice in Canada and having a coach or mentor.

Table 4.

Perceived barriers and supports

Of all IMGs, 54.5% indicated that their first choice of clinical discipline to practise in Canada was specialty practice, and 45.5% chose family medicine. There were no significant differences between Canadian and immigrant IMGs in terms of first choice of clinical discipline (family medicine vs specialty) or preferred community size of practice location (≤ 100 000 vs > 100 000 population).

There were also no significant differences between the groups in the number of times (one time vs two or more times) they had applied to CaRMS in the past, which ranged from one to five times, and in the percentage in each group who obtained interviews for residency positions: 20% of Canadian IMGs and 15.7% of immigrant IMGs. There was, however, a significant difference between the groups in the CaRMS match outcome (P=.000009). The 2002 CaRMS match results revealed that 17 (34%) Canadian IMGs and 43 (10.8%) immigrant IMGs in our study obtained residency positions that year, with 13 (76.5%) and 20 (46.5%) of those matched in each group, respectively, being matched to family medicine.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study of Canadian and immigrant IMGs seeking residency training opportunities in Canada. We present information on their demographic diversity, educational background, and clinical experience. Canadian IMGs tend to be younger, recent graduates, relatively inexperienced in clinical practice, returning to Canada for postgraduate training. In contrast, immigrant IMGs are older, are married with dependent children, and often have postgraduate training and considerable clinical practice experience outside Canada. These differences indicate that immigrant IMGs are at a stage in their personal and professional lives different from that of Canadian IMGs.

The countries (Asia, Eastern Europe, Middle East, and Africa) from which immigrant IMGs most frequently obtained their medical degrees reflect the sources of recent immigration to Canada.7 Canadian IMGs most often chose Asian, Caribbean, or European medical schools, and the reasons for these choices of countries are not completely clear. More than 80% of Canadian IMGs completed their medical training in English, indicating that language of instruction could be an important factor in foreign medical school selection.

Immigrant IMGs have more years of training and clinical practice experience than Canadian IMGs in the countries where they trained. Many immigrant IMGs trained in a language other than English and in a different cultural and medical context. Whether cultural differences pose a challenge to training and practice in Canada, and whether immigrant IMGs tend to practise within their cultural and linguistic communities, is worthy of future investigation. Moreover, the degree to which Canadian IMGs experience cultural and medical contexts similar to the contexts of immigrant IMGs trained in the same countries outside Canada also merits further study.

The finding that fewer Canadian IMGs have taken MCCQE Part 2 is consistent with their demographic and educational characteristics, in that they are younger, recent graduates, with little or no postgraduate training and clinical practice, who wish to return to Canada for residency training. As such, there has been no opportunity for them to challenge the MCCQE Part 2 examination.

Although family medicine was not heavily subscribed to by IMGs overall, it was more frequently selected by IMGs in our study (45.5%) than by Canadian medical school graduates in the first iteration of the 2002 CaRMS match (29.6%, 331/1117).8 The older age of IMGs could, in part, contribute to the preference for the shorter training period that family medicine has to offer. The higher preference for family medicine by IMGs is notable, particularly in light of the decreasing interest in family medicine as an initial match choice by Canadian medical graduates. Ensuring an adequate supply of future family physicians is challenging, and such challenges include filling vacant residency positions arising from the first iteration of the CaRMS match. In the 2002 match, 58% (109/188) of vacant positions at the end of the first iteration were in family medicine, and 76% of the 62 family medicine positions in the second iteration were filled by IMGs.2 This pattern of a first-iteration match leaving family medicine positions vacant and the predominance of IMGs filling vacant positions in the second iteration was also noted in the 2003 and 2004 matches.3,4

Assessing the qualifications of IMG applicants is important for admission to family medicine, particularly assessing current clinical skills accurately.9 Such skills include those related to culture, communication, legal issues, ethical concerns, and health system negotiation. Given the heterogeneity of IMG respondents in our survey, it is perhaps unsurprising that Canadian IMGs fared better in the match than immigrant IMGs. Program directors and their residency training colleagues have a very limited time in which to process second-iteration match applications, and it is likely that applicants with some or a sustained grounding in a Canadian context are perceived to pose fewer assessment challenges than those coming exclusively from educational systems that are unfamiliar.10

Both groups of IMGs reported they applied to CaRMS a similar number of times and were equally successful in obtaining interviews. Our findings do not suggest subgroups of IMGs received different treatment. A relatively greater proportion, albeit few in actual number, of Canadian IMGs actually obtained residency positions through the 2002 CaRMS match. This suggests, given similar interview rates, that the interview is key to obtaining a residency position for IMGs. The finding that a relatively higher percentage of Canadian IMGs were matched to family medicine and that immigrant IMGs were equally matched to a specialty or to family medicine is consistent with the finding that more immigrant IMGs were trained in specialties. For IMGs, prior specialty training could be important in obtaining a specialty residency position in Canada.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The reliability of the self-reported data is unknown. It is possible that some respondents had difficulty understanding some of the questions. While the paper-based version of the questionnaire was pilot-tested, the Web-based version of the questionnaire was not. Respondents are likely to be representative of IMG CaRMS applicants, but are not likely to be representative of all IMGs in Canada. French-speaking Canadian medical schools were not included in the study, as they do not participate in the CaRMS process. This comparative analysis is also based on the assumption that respondents answered accurately the question on immigration status and education; we have no reason to believe otherwise. Given anecdotal evidence, the few Canadian IMGs compared with immigrant IMGs raises the question of whether the number who participated in the CaRMS match indicates the actual number of Canadian IMGs who desire future postgraduate training opportunities in Canada.

Recent years show an increase in the number of IMGs applying to family medicine programs and a decline in the popularity of family medicine as a career choice among Canadian medical graduates. Assuming that Canada wishes to maintain an adequate supply of family physicians, better understanding of barriers that hinder IMGs’ integration into the physician work force and supportive measures that might facilitate integration are needed. The effect of having an increasing number of IMG residents in family medicine residency programs requires thoughtful analysis.

Conclusion

This study describes the demographic characteristics, educational background, and clinical experience of Canadian and immigrant IMGs seeking residency training positions in Canada through the 2002 CaRMS match. Immigrant IMGs are older; have more years of training and clinical experience; and more frequently perceive barriers to assessment, training, and practice. Relatively more Canadian IMGs were successful at obtaining residency positions; most were matched to family medicine. Although family medicine was not heavily selected as the discipline of first choice by all IMGs, it was more frequently selected by IMGs in our study than by Canadian medical school graduates in the first-iteration 2002 CaRMS match.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Health Canada. We thank Gayle Rutherford for conducting the literature review for the overall study, Sheila McDonagh for project management leadership, Carolynn Schmidtke for follow-up tracking and data management, and Shufen Edmondstone for secretarial assistance.

Biographies

Ms Szafran is Research Coordinator in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Dr Crutcher is an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and is Director of the Alberta International Medical Graduates Program at the University of Calgary in Alberta.

Ms Banner is Executive Director of the Canadian Resident Matching Service in Ottawa, Ont.

Dr Watanabe is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Medicine at the University of Calgary.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) Second iteration match results for international medical school graduates 1995-2004. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/statistics/statistics/st_2004#imgs2nd. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) Statistics from the 2002 match. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/statistics/statistics/st_2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) Statistics from the 2003 match. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/statistics/statistics/st_2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) Statistics from the 2004 match. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/statistics/statistics/st_2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crutcher RA, Banner SR, Szafran O, Watanabe M. Characteristics of international medical graduates who applied to the CaRMS 2002 match. CMAJ. 2003;168(9):1119–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) Eligibility. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/applying/eligibility. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Facts and figures 2001. Immigration overview. Immigration by source area and top ten source countries. Ottawa, Ont: Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2002. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pub/facts2001/1imm-05.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) 2002 Career choices of Canadian students & graduates in the first iteration. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2004. [cited 2004 October 22]. Available from: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?.path=./content/statistics/statistics/st_2002#choices. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrew R, Bates J. Program for licensure for international medical graduates in British Columbia: 7 years’ experience. CMAJ. 2000;162(6):801–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates J, Andrew R. Untangling the roots of some IMGs’ poor academic performance. Acad Med. 2001;76(1):43–46. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]