Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine family physicians’ availability to their general practice patients after hours and to explore the characteristics and determinants of after-hours services.

DESIGN

Secondary analysis of the 2001 National Family Physician Workforce Survey.

SETTING

Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Canadian family physicians and general practitioners currently in practice (n=10 553).

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Provision of after-hours care, defined as providing care to all practice patients outside of normal office hours.

RESULTS

Sixty-two percent of Canadian family physicians reported providing after-hours service. The lowest rates were found in Quebec (34%) and the highest in Alberta and Saskatchewan (88%). Respondents practising in academic and community clinics, offering selective medical services (emergency care, palliative care, housecalls, after-hours care), or living outside of Ontario or Quebec were more likely to provide after-hours care. Women physicians, those practising in walk-in clinics, or physicians primarily paid by fee-for-service were less likely to do so. Urban versus rural location, organization of practice (solo or group), age of physician, country of graduation, and physician satisfaction were not found to significantly affect the likelihood of providing after-hours services.

CONCLUSION

Knowledge of these factors can be used to inform policy development for after-hours service arrangements, which is particularly relevant today, given provincial governments’ interests in exploring alternative payment plans and primary care reform options.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer la disponibilité des médecins de famille à l’égard de leur clientèle habituelle en dehors des heures normales, et établir les caractéristiques et les déterminants de ce type de service.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Analyse secondaire de l’enquête 2001 du National Family Physician Workforce.

CONTEXTE

Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Médecins de famille et omnipraticiens canadiens présentement actifs (n = 10 553).

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Prestation de soins après les heures normales, définie comme le fait d’offrir à l’ensemble de la clientèle des services médicaux en dehors des heures normales de bureau.

RÉSULTATS

Les médecins de famille canadiens ont déclaré fournir des services en dehors des heures normales dans une proportion de 62%, les taux les plus bas étant observés au Québec (34%) et les plus élevés, en Alberta et en Saskatchewan (88%). Les répondants exerçant dans des cliniques universitaires ou communautaires, offrant des services, médicaux particuliers (soins d’urgence, soins palliatifs, visites à domicile, soins en dehors des heures normales) ou vivant ailleurs qu’en Ontario ou au Québec étaient plus susceptibles de fournir des services médicaux hors des heures normales. Les femmes et les médecins exerçant dans des cliniques sans rendez-vous ou rémunérés principalement à l’acte étaient moins susceptibles d’en offrir. Le milieu (urbain vs rural) et l’organisation de la pratique (solo vs groupe), l’âge du médecin, le pays d’obtention du diplôme et la satisfaction du médecin n’avaient pas d’influence significative sur la probabilité d’offrir ce type de services.

CONCLUSION

La connaissance des facteurs qui influencent la prestation de services de santé en dehors des heures normales est importante pour le développement des politiques concernant ce type de services, une question bien d’actualité, alors que les gouvernements provinciaux envisagent des plans de rémunération alternatifs et des réformes éventuelles des soins primaires.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This secondary analysis of the 2001 National Family Physician Workforce Survey was designed to determine availability of after-hours care by family doctors across Canada.

Overall, 62% of family doctors provided some form of after-hours care, by telephone or in person.

The highest rates of coverage were in Alberta and Saskatchewan and the lowest in Quebec. Those working in academic or community clinics, working in emergency rooms, providing housecalls or palliative care, or working in after-hours clinics were more likely to provide after-hours care.

Women and those earning more than 75% of their income through fee-for-service were less likely to provide after-hours care. Age, setting, and type of practice did not influence after-hours care.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Cette analyse secondaire de l’enquête 2001 du National Family Physician Workforce voulait établir la disponibilité des médecins de famille canadiens pour offrir des services médicaux en dehors des heures normales.

Dans l’ensemble, 62% des médecins de famille offraient un type quelconque de service après les heures normales, au téléphone ou en personne.

L’Alberta et la Saskatchewan avaient les plus forts taux de couverture et le Québec, le plus faible.

Les femmes et les médecins dont plus de 75% du revenu provenait de la rémunération à l’acte étaient moins susceptibles de fournir des services en dehors des heures normales. L’âge, le contexte et le type de pratique n’avaient pas d’influence sur la prestation de ces services.

One of the most controversial issues in primary care reform in Canada is the commitment to 24-hour, 7-day-a-week access to primary care, with family physicians and general practitioners providing on-call and weekend services, and with telephone triage of after-hours calls. To develop informed policies concerning this topic requires an understanding of the characteristics of on-call duties and after-hours care.

A review of the literature on on-call and after-hours care by family physicians revealed few Canadian studies. An early survey by Koffman and Merritt1 reported on after-hours services provided by a single health centre in rural Ontario, in which all calls were answered by an on-call physician. Patel et al2 surveyed pediatricians and family physicians in Toronto, Ont; Winnipeg, Man; Ottawa, Ont; and Montreal, Que. The authors were particularly interested in identifying the extent to which parents of ill children were able to talk directly to a physician. Their findings suggested considerable regional variation in physicians’ availability after hours (range 28% to 87%).

As there is little published research on after-hours care in Canada, it is necessary to understand current medical practice before we can determine future directions for primary care reform.

An invaluable source of information on family physicians in Canada is the National Family Physician Workforce Survey (NFPWS). The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) has conducted the survey periodically since 1997. The 2001 NFPWS indicated that 73% of the surveyed doctors participated in “on-call activity.”3 In the NFPWS, on-call activity is defined as “time outside of regularly scheduled clinical activity during which you are available to patients.”4

The phrases after-hours care and on call are not exactly synonymous in the Canadian medical environment. We define after-hours care, in the context of family practice, as providing care to all practice patients outside of normal office hours. While after-hours care is often provided using an on-call system, being on call can also refer to coverage of only certain patients, such as obstetric and long-term care patients, or hospital inpatients. On call might also be viewed as requiring physicians to be available to provide care, whereas after-hours care is patients’ ability to access care outside usual office hours. This paper is intended to determine the availability of family physicians and general practitioners (hereafter referred to as family physicians) to their general practice patients after hours. We used data collected as part of the 2001 NFPWS to explore the characteristics and determinants of after-hours services in Canada in relation to physician- and practice-related variables.

METHODS

The 2001 NFPWS was a self-reported questionnaire mailed to all family doctors in Canada. The questionnaire contained items relating to practice setting, working hours, services respondents provide, access to health care resources, demographic characteristics, and on-call services.

The survey was conducted between February and June 2001. In total, 27980 physicians were sent a questionnaire. Responses were received from 14319 physicians, a response rate of 51.2%. From this number, 1231 respondents were deemed ineligible because they were retired, medical residents, administrators, researchers, or on leave. This left an eligible sample of 13088 family physicians.

To ensure that only physicians who regularly practise general family medicine were included in our analysis, we conducted a further screening. Respondents were deemed eligible for inclusion if they reported that their main practice setting was a private office or clinic, community clinic or community health centre, academic family medicine teaching unit, or free-standing walk-in clinic. As well, respondents had to report that at least one family physician (ie, themselves) worked in their main practice setting.

Respondents whose main practice setting was reported as being a nursing home, hospital inpatient unit, or emergency department, or who, for whatever reason, reported that no family physicians worked in their main practice setting, were excluded from the analysis. Following this screening, 10553 family physicians remained in the sample for analysis.

To determine access for general practice patients, respondents were categorized into an “after-hours services group” if they reported providing telephone or in-person on-call services for nonhospitalized patients. Rural physicians providing emergency room on-call services were also included in the after-hours services group, as rural physicians sometimes provide medical services for their general practice patients directly through the emergency department. Rural physicians were identified in the questionnaire if they described their practice as rural or geographically isolated. Those who reported providing no on-call services, only obstetric, hospital inpatient, or emergency room on-call services in a non-rural practice, were included in the “no after-hours services group.”

Differences in response rates between men and women, and between health regions, were identified in the original sample3; both of these differences have been found to affect practice patterns.3 To minimize response bias, the CFPC used population weighting on the original sample to generate estimates of the total family physician population. Weights were calculated by dividing the total population of a specific segment of the population (eg, Toronto female physicians) by the respondent population (Toronto female respondents). This process is described in detail in the database documentation.3 A problem with use of population weights in statistical analysis is that they inflate the sample size and increase the risk of committing a type I error. To avoid this problem, analytic weights were calculated on the subsample used for this analysis by dividing the population weights for each person in the sample by the average weight for the sample. These weights correct for nonresponse bias while maintaining the original sample size.5

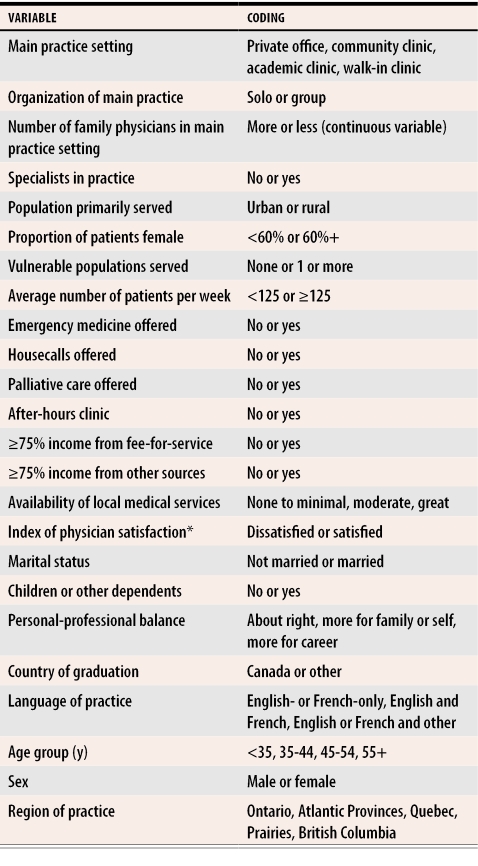

Data analysis included bivariate and multivariate techniques. Bivariate analysis was used to identify potential explanatory variables for the outcome (P < .01). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between the outcome variable and potential predictors, while adjusting for other identified explanatory variables. All potential explanatory variables for the regression model are presented in Table 1. Models were run using a backward stepwise selection algorithm. Variables were retained in the model if the significance level for the Wald inclusion test statistic was .01. All data manipulation and analysis was done using SAS (version 8.2). Ethics approval was obtained through the Laurentian University Ethics Review Board.

Table 1. Candidate independent variables in logistic regression model.

Reference category is italicized.

*The index of physician satisfaction was created from three questions in which respondents were asked to rate, using Likert scales, their level of satisfaction with hospital relationships, specialist physician relationships, and current professional life.

RESULTS

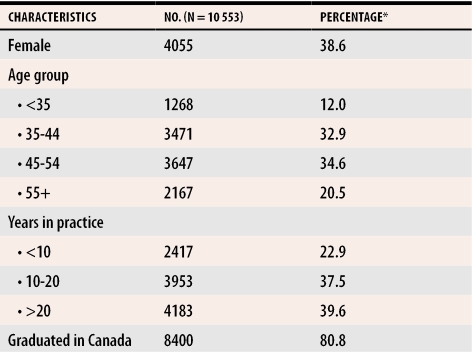

Of the 10 553 respondents, approximately 39% were female, 55% were older than 45 years, and roughly 40% had been in practice for more than 20 years (Table 2). Approximately 81% of respondents reported having graduated in Canada.

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents

*Percentages are based on the number of respondents from the sample for each question.

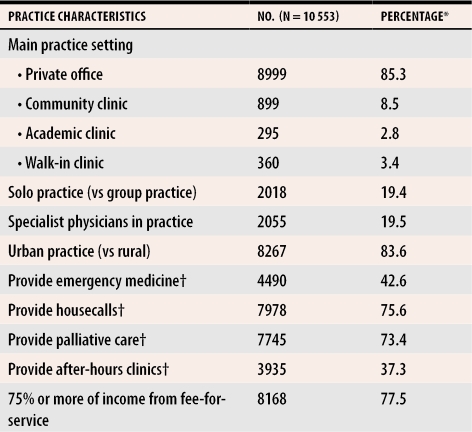

Most (85.3%) reported practising in private offices, followed by community clinics (8.5%; Table 3). Approximately 19% of family physicians were in a solo practice. Around three quarters reported providing housecall services or palliative care services, while less than half reported offering emergency medicine or after-hours clinics. The primary source of income for most respondents was reported to come from a fee-for-service pay structure.

Table 3.

Practice profile of family physicians

*Percentages are based on the number of respondents from the sample for each question.

†Services reported to be provided to “regular patients only.”

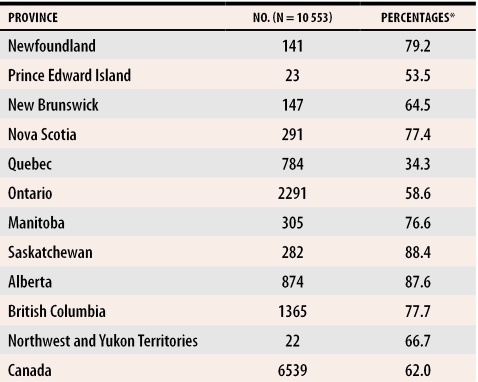

The 2001 NFPWS results descibing provision of after-hours care in Canada for our study physicians are listed in Table 4. By province, the highest rates of after-hours coverage were seen in Saskatchewan and Alberta, where 88.4% and 87.6% of family physicians, respectively, reported providing the service (Table 4). In contrast, only 34.3% of family physicians from Quebec provided the service. Across Canada as a whole, 62% of respondents provided after-hours services.

Table 4.

Provincial breakdown of family physicians providing after-hours care

*Percentages are based on the number of respondents from the sample for each question.

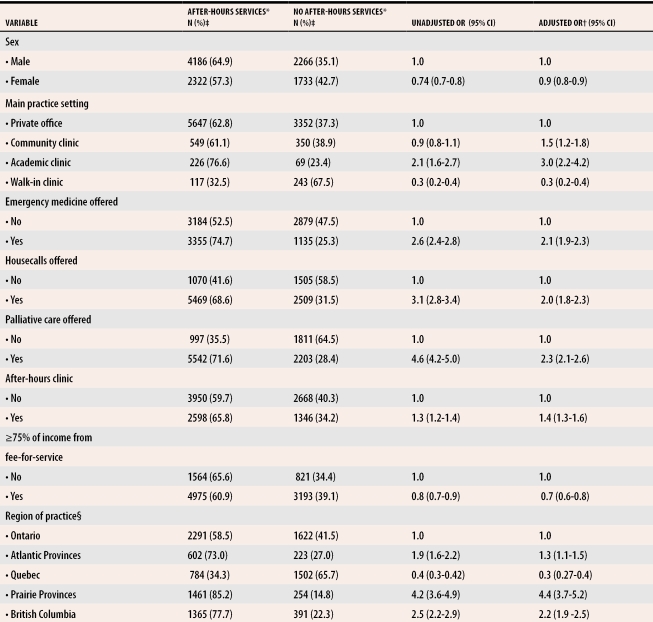

Logistic regression analysis (Table 5) showed that a respondent’s main practice setting was significantly associated with whether after-hours care was provided. Those practising in academic clinics were three times more likely (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.0, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2-4.2) and in community clinics were 1.5 times more likely (OR 1.5, CI 1.2-1.8) than those in private offices to provide after-hours services, whereas those whose main practice settings were walk-in clinics were less likely (OR 0.3, CI 0.2-0.4) to do so. Family physicians offering emergency medicine (OR 2.1, CI 1.9-2.3), housecalls (OR 2.0, CI 1.8-2.2), palliative care (OR 2.3, CI 2.1-2.6), or after-hours clinics (OR 1.4, CI 1.3-1.6) to their regular patients were more likely to provide after-hours services than those who did not. By region, family physicians in the Prairie Provinces (OR 3.7, CI 2.8-5.0), British Columbia (OR 2.2, CI 1.9-2.5), and the Atlantic Provinces (OR 1.3, CI 1.1-1.5) were significantly more likely to provide after-hours services than physicians in Ontario, whereas family physicians in Quebec were less likely (OR 0.3, CI 0.27-0.4) than Ontario doctors to do so. Female respondents (compared with male; OR 0.9, CI 0.8-0.94) and those who reported more than 75% of their income from fee-for-service (compared with less than 75%; OR 0.7, CI 0.6-0.8) were less likely to provide after-hours services. Variables that did not remain in the model, and were, therefore, not found to be associated with provision of after-hours services, include organization of practice (solo or group), population primarily served (urban or rural), age group, country of graduation (Canada or other), and physicians’ satisfaction.

Table 5.

Results of logistic regression analysis of factors associated with provision of after-hours services

CI—confidence interval, OR—odds ratio.

*Services were reported to be provided to “regular patients only.”

†A backward stepwise selection procedure was used to select the model from the variables listed in Table 4.

‡Percentages are based on the number of respondents from the sample for each question.

§For the variable “region of practice,” due to small numbers of eligible respondents, the Northwest and Yukon Territories were excluded from the analysis (n=33), and the Prairie Provinces and the Atlantic Provinces were analyzed as regions.

DISCUSSION

In Canada, approximately two thirds of family physicians are available to their patients after hours. The highest rates of after-hours coverage were seen in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and the lowest in Quebec. The 2001 NFPWS report3 indicated that 73% of family physicians provide on-call services, approximately 11% more than our analysis suggests. This difference can be accounted for by the exclusion from our analysis of respondents whose practices do not fit into a family practice profile (eg, hospital inpatient units and emergency departments) and of those who report providing on-call services only to certain patient populations, such as obstetric patients or hospital inpatients. These findings suggest a need for caution when large surveys and policies are based on statistics that encompass a variety of practice profiles.

The reported regional differences in levels of after-hours services aligns with the earlier work of Patel et al.2 These differences could reflect variation in provincial legislation requiring after-hours care6 or the availability of telephone advice systems. Alternatively there might be a “herd effect” whereby once most physicians offer (or do not offer) a service, it becomes the standard pattern of care for that community. Physicians in community clinics and academic centres could be more likely to provide on-call services because this is often a condition of service and they are supported by a team that includes residents or nurse practitioners.

The fact that physicians providing palliative care or housecalls, or holding specific after-hours clinics, are more likely to be available after hours might indicate that these physicians feel a social responsibility to provide access to care. As these services are often provided outside regular office hours, these physicians could already be working when their offices are closed and are likely already on call for some patients in their practices. The finding that physicians who receive less than 75% of their income from fee-for-service arrangements were more likely to provide after-hours care supports the idea that alternative payment plans are able to pay more for traditional doctor-patient office encounters. Female respondents were slightly less likely to provide after-hours care than their male colleagues, possibly because they have greater family responsibilities, spend more time on indirect patient care, or do more obstetric care (in lieu of after-hours care).7

Even more interesting are variables that were not significant in the multivariate model. Most notable were age, rural versus urban location, organization of practice (ie, solo or group), and physicians’ satisfaction. Our data do not support perceptions that, for example, young doctors are not pulling their weight or that city doctors work only from 9 to 5.

This research improves our understanding of factors that influence provision of after-hours care. There are, however, several limitations to this study. First, only about half the eligible family physicians across the country returned completed questionnaires. Nevertheless, the size of the sample achieved allows us to be reasonably confident that our findings reflect common experiences among Canadian family physicians. Second, the 2001 NFPWS questionnaire was not designed with our research objectives in mind. Including emergency on-call service as a type of after-hours coverage for general practice patients probably overestimates the actual availability of physicians. Emergency room on-call duty was included to capture the model of care often used in smaller communities where a physician is on call through the emergency department. Finally, just because physicians answering the questionnaire do not provide after-hours care does not necessarily mean that patients are not covered. For example, physicians might have arrangements within a practice group to be exempt from after-hours care in exchange for other services, such as obstetric call or attending evening and weekend clinics.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that approximately two thirds of Canadian family physicians provided after-hours services; the lowest rates were reported in Quebec and the highest in the Prairie Provinces. Practice setting, services offered, region of practice, and principal payment method were all found to be important factors affecting provision of after-hours care. Knowledge of these factors can be used to inform policies regarding after-hours service arrangements, which is particularly relevant today given provincial governments’ interest in exploring alternate payment plans and primary care reform options. Providing physicians and policy makers with reliable data on provision of services in their area, and in the country as a whole, lays the ground either locally or provincially for organized systems for providing after-hours care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shari Gruman for her input and assistance in preparation of this manuscript. We thank Sarah Scott for her time and expertise related to the National Family Physician Workforce Study Database and questionnaire. We also thank the members of the North Toronto Primary Care Research Network (Nortren) for their support. Funding for the project was provided in part from the CFPC’s Janus Research Grant. The study described in this paper was conducted using original data collected for the CFPC’s National Family Physician Workforce Database. This database is part of the CFPC’s Janus Project: Family physicians meeting the needs of tomorrow’s society, which was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the Canadian Medical Association, La fédération des médecins omnipracticiens du Québec, Health Canada, Scotiabank, Merck Frosst, and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Biographies

Mr Crighton is a doctoral candidate at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, and a Research Associate in the Primary Care Research Unit at Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ont.

Dr Bordman is Professional Development Director at the Scarborough Hospital and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr Wheler is a Lecturer in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Ms Franssen is a Biostatistician at GlaxoSmithKline in Toronto.

Dr White is Chief of Family and Community Medicine at North York General Hospital and an Associate Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Ms Bovett is a Registered Nurse and Research Assistant with the North Toronto Primary Care Research Network.

Dr Drummond is an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Calgary in Alberta. All the authors are members of the North Toronto Primary Care Research Network and the After-hours Care Research Group.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Koffman BD, Merritt K. Analysis of after-hours calls and visits in a family practice. J Fam Pract. 1978;7:1185–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel H, Macarthur C, Feldman W. Where do children go? Comparing the after-hours availability of family physicians and primary care pediatricians in four Canadian cities. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:1235–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.College of Family Physicians of Canada. Updated data release of the 2001 National Family Physician Workforce Survey. Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2002. [cited 2004 April 5]. Available from: http://www.cfpc.ca/local/files/Programs/Janus%20project/NFPWS2001_Final_Data_Release_rev_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.College of Family Physicians of Canada. The National Family Physician Survey 2001. Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2002. [cited 2004 Jan 29]. Available from: http://www.cfpc.ca/local/files/Programs/Janus%20project/NFPWS2001_Questionnaire_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goel V. Analysis of complex surveys. November 5, 1993. Toronto, Ont: Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordman R, Wheler D, Drummond N, White D, Crighton E. [cited 2005 Sept 14];After-hours coverage. National survey of policies and guidelines for primary care physicians. 2005 51:536–537. Available from: http://www.cfpc.ca/cfp/2005/apr/vol51-apr-research-2.asp. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Scott S, Gutkin C, Newbery P, Busing N, Grava-Gubins I, Ieraci L. [cited 2005 Sept 14];Responding to societal needs: a focus on older family physicians, female family physicians, and recent family medicine graduates. Results from the: 2001 National Family Physician Workforce Survey. Presented at NAPCRG 2003 Banff, Alberta. Available from: http://www.cfpc.ca/English/cfpc/research/janus%20project/default.asp?.s=1.