Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To understand why Canadian adolescents go or do not go to see family physicians for annual checkups using the Theory of Planned Behavior as a conceptual framework.

DESIGN

Qualitative analysis of small group discussions.

SETTING

Edmonton, Alta, a large Canadian city.

PARTICIPANTS

Seventeen adolescents (6 male, 11 female) recruited from a medical clinic and an organized youth group.

METHOD

Two small group discussions and one validation focus group were held. A combination of category coding and thematic analysis was used to analyze the data transcribed.

MAIN FINDINGS

Adolescents reported that regular checkups, although uncomfortable, are a good idea. They also reported that going to a family doctor for a checkup is out of their control because of numerous barriers (eg, lack of time, not knowing how to set it up, or lack of transportation). Participants thought their parents’ opinions on going for routine checkups were more important than the opinions of their peers.

CONCLUSION

Family physicians should recognize adolescents’ attitudes toward visiting family physicians’ offices and understand the potential barriers adolescents face in coming in for checkups in order to make visits to their offices more comfortable and beneficial.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

À l’aide de la théorie du comportement planifié comme cadre conceptuel, établir les raisons pour lesquelles les adolescents canadiens choisissent ou non de consulter un médecin de famille pour un bilan de santé annuel.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Analyse qualitative de discussions en petits groupes.

CONTEXTE

Edmonton, Alberta, une grande ville canadienne.

PARTICIPANTS

Dix-sept adolescents (6 garçons et 11 filles) recrutés à partir d’une clinique médicale et d’un groupe de jeunes organisé.

MÉTHODE

Deux discussions en petits groupes ont été tenues, suivies d’une validation par un groupe de discussion. Les données transcrites ont été analysées par une combinaison de catégorisation et d’analyse thématique.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

D’après les adolescents, les examens de santé périodiques sont une bonne idée, même s’ils ne s’y sentent pas toujours à l’aise. Ils ajoutent qu’il leur est souvent très difficile de consulter un médecin pour un tel examen en raison de nombreux obstacles (manque de temps, ou d’un moyen de transport, ne pas savoir comment procéder). Ils sont d’avis que l’opinion de leur parents au sujet des examens de santé périodiques vaut mieux que celle de leurs pairs.

CONCLUSION

Les médecins de famille devraient mieux connaître les attitudes des adolescents qui songent à les consulter et les obstacles que ces jeunes rencontrent lorsqu’ils viennent pour un examen de santé, de façon à pouvoir rendre leurs visites au bureau plus confortables et plus profitables.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This qualitative study explores how young adolescents viewed having checkups with family doctors and focused on the barriers to their doing so.

Although adolescents think that having checkups is a good idea, few had followed through with making appointments.

They identified barriers that included difficulties with transport, being dependent on parents, not knowing how to make appointments, and perceived long waiting times.

Parents, not their peers, were seen as the preferred source of health information besides physicians. Girls preferred to see female physicians. All agreed that having a relationship with a family doctor made it easier to attend.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Cette étude qualitative voulait connaître l’opinion des jeunes adolescents sur l’idée de consulter un médecin de famille pour un bilan de santé, ainsi que les obstacles qu’ils rencontrent en le faisant.

Même s’ils considèrent que l’idée d’un examen de santé est bonne, peu d’entre eux y donnent suite en prenant rendez-vous.

Les obstacles signalés incluent les difficultés de transport, la dépendance à l’égard des parents, le défaut de savoir comment prendre rendez-vous et la crainte de longues attentes.

Après le médecin, leur principale source d’information sur les questions de santé sont les parents plutôt que les pairs. Les filles préfèrent consulter une femme médecin. Tous déclarent que les visites sont plus faciles lorsqu’ils ont un lien quelconque avec un médecin de famille.

The health of adolescents should be a major concern for Canadian society. The World Health Organization defines adolescence as ages 10 to 19.1 During adolescence, teens experiment with smoking, alcohol, other drugs, and sexual activity; a recent survey reported that one third of Canadian adolescents are current smokers, and nearly half drink alcohol regularly (one or more drinks per month).2 This adolescent behaviour can lead to lifelong problems.3

Family physicians might be able to influence adolescents’ behaviour.4 Walker and Townsend’s review of how family physicians affect adolescent health5 stated that, although there are several reports in adults,6-8 there are few reports of systematic health checks among teenagers and that only one study reported the effect of the intervention. The authors concluded that the effect of screening and of physicians’ intervention in changing behaviour require further evaluation.5

In a subsequent publication, Walker et al described a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of primary care consultations on 132 adolescents.9 Results showed that consultation had a positive effect on patients’ health-related behaviour (smoking, drinking alcohol, nutrition, and sexual activity) relative to control subjects who did not see primary caregivers.

Despite support for particular interventions, the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination recommended in 1979 that annual checkups should be abandoned.10 Despite this recommendation, most family physicians still regard them as the cornerstone of preventive care.6 The Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care lists several screening and prevention interventions for which there is supporting evidence.11 In the list are 15 interventions recommended for adolescents and an additional nine interventions recommended for high-risk populations.11 As Katz said for adults, it is unlikely that busy family physicians will be able to incorporate these preventive interventions into a 15-minute appointment and address the original reason for the visit.7

Several guidelines, created to help busy family physicians improve adolescent health, suggest that patients receive regular checkups during adolescence.12,13 During these visits, family physicians can do physical examinations, screen for health-compromising behaviour, and as with the adult population, try to develop important relationships with the adolescents they see. Unfortunately, adolescents come to family physicians’ offices for checkups less frequently than average Canadians do.14

Why do adolescents not seek health care from family physicians? A Canadian study by Oandansan and Malik examined the views of adolescent girls on their experiences at family doctors’ offices.15 They reported that the girls preferred friendly female physicians and wanted to be acknowledged as teenagers. Results of this study should be interpreted with caution, however, because only adolescents who actually saw a family physician were recruited, the views of only female adolescents were solicited, and the results were not framed in relation to theories of how adolescents make health decisions. Our study addressed these limitations by using a theoretical framework (the Theory of Planned Behavior [TPB]16) to understand how adolescents make health decisions, by recruiting both male and female adolescents, and by including the opinions of adolescents who had not had recent checkups along with the opinions of those who had.

According to TPB, the most important predictor of any behaviour (eg, seeing a physician for an annual checkup) is an intention to behave in that way. Intention, in turn, is determined by attitude toward performing the behaviour, subjective norms in relation to the behaviour, and perceived control of the behaviour. Attitudes are defined as the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable opinion of the behaviour. Subjective norms are perceived social pressures to perform or not perform the behaviour. Perceived control of the behaviour is a person’s belief about how easy or difficult it is to behave that way. Although TPB has been used to understand a range of health behaviour, a review indicated that no published research has used TPB to understand adolescent decision making in relation to seeing a family physician.17

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study to elicit information on attitudes, social norms, and perceived control of behaviour in relation to going for regular checkups and to determine whether there were other important issues that facilitate or prevent such visits that fall outside the purview of the TPB. We hoped to identify factors that would help make visits to family physicians’ offices appeal more to adolescents, by improving the comfort and benefit of the experience for them.

METHODS

We used the TPB as a conceptual framework for understanding why adolescents do or do not see family physicians and to help design more effective interventions.16 Failing to use a conceptual framework risks omitting important considerations in development of intervention strategies.18

We chose qualitative methods for understanding adolescents’ perspectives on visiting family physicians for annual checkups. Qualitative methods are useful in this context because they are designed to describe rather than explain behaviour.19 Also, while there is considerable quantitative research on the TPB in relation to health behaviour, the TPB has not been examined specifically in relation to adolescents’ decisions to see family physicians. Finally, because the TPB might not be applicable to all adolescents, qualitative methods allowed us to explore additional barriers and facilitators to seeing family physicians.

Sample

A purposive sample of key informants was recruited for the study. Inclusion criteria were English-speaking, 13 to 15 years old, and currently residing in Edmonton, Alta. Informants could be male or female and with or without a family physician. Key informants were defined as people within the group of interest who possessed information connected to the topic of research and had a relationship (possibly brief, as in the case of a discussion or interview) with the researcher.20 The rationale for the age range we chose was that, after age 12, adolescents tend not to come in for regular checkups,13 and we wanted to explore their ideas during that time. Also, because risky behaviour increases as adolescents age (a substantial proportion of 15- to 17-year-olds already put their health at risk14), we wanted to emphasize the importance of targeting adolescents at an earlier age. Hence, we chose 13- to 15-year-olds for this study. Both male and female adolescents were included to ensure opinions from both groups were represented. To maximize the variety of opinions generated during the discussions, we tried to recruit adolescents from various socioeconomic backgrounds.

Participants were recruited through one family medicine clinic and one organized adolescent group in Edmonton. Recruitment targeted adolescents from various socioeconomic backgrounds and those who had had checkups by family doctors within the last 12 months as well as those who had not. All potential participants were sent an information package containing a consent form that interested adolescents had to mail back to the primary investigator. These adolescents were then notified by telephone of the time and location of the small group discussion. Other adolescents were recruited using the snowball sampling method.20

Procedure

Two small group discussions were followed by a validation focus group to confirm or elaborate on themes identified during the discussions. We used groups to encourage participation and because the interaction between members would likely generate more ideas than would be gained by interviewing the adolescents individually. The groups were kept small to ensure that all members had the opportunity to participate. The validation group was then convened to determine whether themes presented by the previous groups would be supported.

Each discussion group followed a semistructured interview guide and was conducted by the principal investigator. We used a funnel approach, beginning with questions relating to adolescents in general and moving to specific areas. The questions focused on key constructs within the TPB, including attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control of behaviour; several probes were used to further discussion and clarify ideas.

The first part of the validation focus group discussion was aimed at determining whether new ideas about going to a family doctor for a checkup would be generated. Open-ended questions probed areas such as general impressions, advantages, disadvantages, and people who would encourage or discourage going for a checkup. The second part was a focused discussion of the themes elicited from the previous groups to determine whether these themes were valid.

Analysis

Discussions were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Category codes were assigned to sections of text by the principal investigator20,21 to identify distinct topics for more detailed analysis. Following identification of topics, themes were identified from the discussions by systematically analyzing each participant’s comments (within-participant) and the groups’ comments (between–participant).

Within-participant analysis.

Themes emerged from examining the transcribed comments of each teenager independently and analyzing data from that one person. Major themes brought out by individual participants were listed separately along with the corresponding sections of text (for verification) before the next participant’s comments were analyzed. After major themes were identified for each participant, a master list of major themes was compiled.

Between-participant analysis.

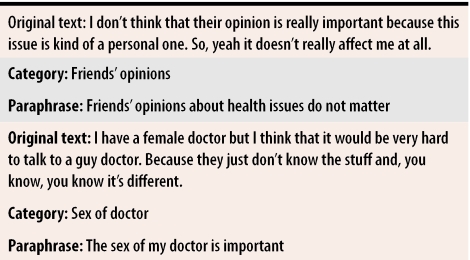

Comments from several adolescents were analyzed as a group. All the transcribed text for any adolescent coded with a particular topic category was examined. To reduce these data to a more manageable form for description, sections of original text expressing the same meaning within a topic category were assigned paraphrases (Table 1). The analysis aimed to reduce the raw data from each focus group discussion into paraphrases of experiences addressing the research questions and to compare these paraphrases across transcripts to identify common ideas.

Table 1.

Example of paraphrase generation

Thematic analysis principles22 were used to reduce the raw data; phenomenologic methods23 were used to guide development of paraphrases and comparisons. Paraphrasing was done by the principal investigator and was verified by the two other researchers. Disagreements were infrequent and were resolved through discussion.

The Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Alberta approved the study.

FINDINGS

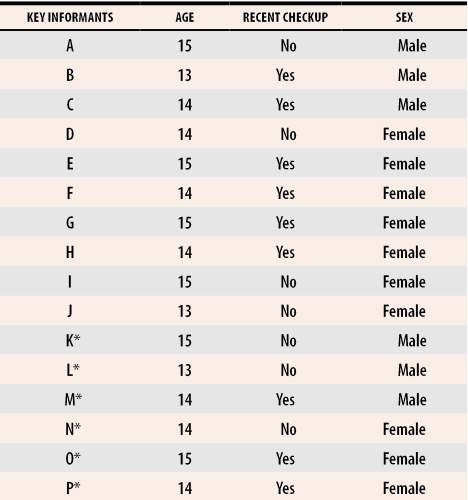

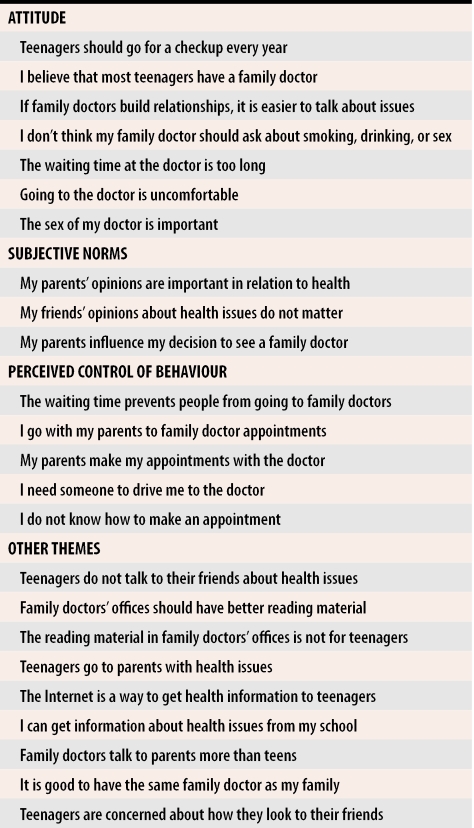

Table 2 shows the age and sex of study participants and whether they had had checkups in the last 12 months. Participants’ comments reflected their attitudes, subjective norms, perceived control, and intentions. Main themes are listed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of key informants

*Participated in validation focus group.

Table 3.

Main Themes

Attitudes

Most participants thought that going to a family doctor for a periodic checkup was a good idea and that it was an opportunity to find out whether anything was wrong with them and ask questions about their health. In general, they agreed that teenagers should go for checkups each year. One participant said, “I think that you should go at least once a year.” Another said he thought most teenagers went for checkups: “I think that every single one of my friends do. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t, and everyone just goes for the yearly checkup.”

A main theme uncovered during the analyses was the importance (to teenagers) of having a doctor they know. They said they felt more comfortable if doctors tried to build relationships with them. One commented, “You know the person so it’s not as uneasy, like it’s easier to talk to them about things.” Another said, “It just feels more comfortable when they build a relationship with you.”

Waiting times were also a prominent theme. Participants thought the waiting time was too long. Several participants said waiting for the doctor was frustrating: “You’re waiting there on the time you are supposed to be, and then half an hour after that they finally call you in. And then it takes forever and then you’re late for whatever you’re supposed to do after.”

The teenagers thought going to a doctor was uncomfortable, but more comfortable than going to a walk-in clinic or emergency department: “If you go to just any doctor, like a walk-in doctor, I don’t think they know you as well. [Family doctors] make it more comfortable just because you have seen them before.” “So it’s nice going in and having somebody that knows your name.”

The sex of the physician was important. Female participants had a strong preference for female family doctors. One said, “I have a female doctor, but I think that it would be very hard to talk to a guy doctor. Because they just don’t know the stuff, and you know it’s different.” Another commented, “I think you’re just being more comfortable; it just seems that more people are comfortable with a girl if you are a girl and a guy if you are a guy, kind of thing.”

Male participants did not have a sex preference: “I don’t really care. Because I am a guy … it’s fine if you’re a female doctor.”

Subjective norms

Parental influence emerged as a main theme. The teenagers clearly stated that the greatest influence on their going to a family doctor was their parents. Most teenagers went for checkups when their parents scheduled the appointments: “I personally just ask my parents and … get their opinion first. [I would ask whether] I needed an appointment, and if so, they would probably take the action in arranging it.”

One interesting result of this study was the teenagers’ statements that their friends’ opinions do not matter when it comes to health issues. One said, “I don’t think that their opinion is really important because this issue is kind of a personal one. So, yeah, it doesn’t really affect me at all.” Another teenager described the effect of friends, “In like other things I would listen to them, but in health things no. I don’t really care what they say.” This major theme arose from both initial small group discussions and was confirmed by the validation group. It was interesting because peer pressure and peer-group opinions are often thought to strongly influence teenagers’ decisions.

Perceived control

The perceived control element of the TPB allows prediction of behaviour that is not under a patient’s complete control. Several factors raised in this study demonstrated that going to a family doctor is not a completely voluntary act. Several adolescents reported that they did not know how to make an appointment for a checkup: “I don’t know how to make an appointment so I can’t.” When asked how they would make an appointment if their parents were not available, one teenager responded, “I don’t know how. I guess you would just phone in, but how would I get there? Take the bus or something. You are kind of dependent on your parents to drive you there too. Things like that.” Most participants relied on their parents to make appointments for them, and most were accompanied to the doctor’s office by their parents.

Restricted office hours affect teenagers’ ability to go for checkups. Most doctor’s offices were open only when most teenagers were in school. For those who went to appointments with their parents, these parents’ work schedules affected their teenagers’ ability to go to the doctor. The time required for appointments was also raised as a barrier to getting a checkup, as was the need for someone to drive them to the clinic: “Well, I would have to get a ride there, but if I did not want my mom to know about it then I wouldn’t be able to go.”

Intentions

One of the most interesting findings, which was consistent with our own experiences with teenagers, was that they did not intend to go to family doctors for checkups. Participants indicated that teenagers went when their parents booked appointments but did not plan or initiate scheduling periodic checkups: “I find out the day it happens. Like my parents were, ‘You have a checkup at 3 o’clock today.’”

Several participants commented that they thought it was a good idea to go and that they expected that they would go when their parents set up appointments for them. This is an area for further examination. We are aware of no published study examining adolescents’ intention to see their family doctors.

Other themes

Outside the context of the TPB, a main theme that emerged was communication among teenagers. From the discussions, it appeared that teenagers did not talk about personal health issues with their friends. One said, “Yeah, I know that I really do not talk to my friends about health issues. Just cause we really don’t talk about stuff like it doesn’t come up in everyday subjects.” Another commented, “I think they keep it a little bit more private and [do] not talk about it because they have to keep up an image of being tough and stuff.” This was unexpected. We thought teenagers would discuss their health more readily with their peers.

Another main theme was family doctors’ communication style. Participants felt that family doctors directed their conversation toward the parents. Adolescents stated they felt left out of the discussions. One said, “It’s my foot that’s broken. Ask me. I probably know how much it hurts more than she does.” Some participants thought some doctors used language they did not understand. Another asked, “Is that some condition of my foot or do I have a brain problem or what?”

Validation group

The validation group supported the themes identified in the small group discussions and introduced a couple of new themes. For example, the validation group discussed teenagers’ use of emergency departments: “I sprained my elbow or something. So I went to the emergency room; [they] gave me a sort of half cast thing.”

Previous literature supports the idea that teenagers rely heavily on emergency services for primary care.24 We also tried to ascertain which teenagers might not go to family doctors. Two participants offered the following suggestions: “If you don’t have any money and you don’t have a health plan, then you probably don’t go and see a doctor as much as other people.” “Maybe, like, teenagers on drugs that don’t want the doctor to find out and then tell their mom or something.”

Disagreement among key informants

One topic discussed by participants related to questions about lifestyle issues that family doctors might ask adolescents. The teenagers disagreed on whether questions should be asked about smoking, drinking, drug use, and sexual behaviour. Some thought these issues affected their health and thus should be asked, while others thought they should not be asked unless teenagers themselves introduced the topic: “I don’t think that they should just come out with it; they should have secret ways of finding it out.” “I think that the doctor should ask about your lifestyle like the choices you make and kind of that would be a way for him to get more information.” Since much behaviour risky to health has been documented in this population, it is clear that questions about these activities should be asked during checkups.14

DISCUSSION

The incidence of behaviour that poses risks to health is rising among adolescents in Canada.9 The long-term health consequences of this behaviour are immense. Results of this study enhance our understanding of Canadian adolescents’ perspectives on decision making in relation to annual checkups from their family physicians. The adolescents in this study did not think that teenagers intend to go to family doctors for periodic checkups, but they did think that checkups, although uncomfortable, were a good idea. The experience is better if the doctor is someone they know and (for female participants) is of the same sex. They thought their parents’ opinions on going for checkups was much more important than the opinions of their peers. Results of this study provided evidence that going to a family doctor for a checkup is not completely within adolescents’ control: they do not always know how to make appointments, and they find it difficult to make time for appointments and to find transportation to doctor’s offices.

Several of our findings are supported in previous literature. Our study builds on previous research by Oandasan and Malik on female teenagers.15 That study found that going to the doctor is thought to be uncomfortable, a finding that is consistent with our research.15 Oandasan and Malik concluded that building strong doctor-patient relationships with adolescent patients is crucial to developing positive attitudes that teenagers will carry with them the rest of their lives.15 Our study found that teenagers liked the fact that doctors took the time to get to know them as people. Oandasan and Malik also reported that adolescent girls preferred female physicians15; our study found that this sex preference does not hold true for male teenagers. As far as we know, this has not been previously reported in the literature.

The idea that waiting time at doctors’ offices constitutes a barrier to health care was not presented in the study by Oandasan and Malik. In our study, waiting time was a prominent theme among participants, who thought it was too long. This finding has been published in studies of adults. Several authors have reported that adults rank waiting time as patients’ area of greatest dissatisfaction when assessing the care they received from their family doctors.25,26 Gribben showed that long waiting times were associated with less use of health care in a New Zealand population.27 If the wait at family doctors’ offices discourages teenagers from seeking care, this is an area for further research.

Teenagers reportedly go to family doctors less often than the rest of the population.14 In this study, participants thought that going to a doctor was a good idea, and in fact, most thought their peers went for checkups regularly, even though half the participants had not been to a doctor for a checkup within the past 12 months. Selection bias might explain this discrepancy. Some participants were recruited through a medical clinic, and therefore, might have a more positive view of the usefulness of going for a checkup than those who did not volunteer.

Previous literature showed the influence of parents and friends on adolescents’ behaviour.28 We did not expect parental influence to be so strong. It is interesting because peer pressure and peer opinion are commonly thought to be very important for teenagers. It suggests that peer influence might have little effect on adolescents’ decisions to go for checkups. One possible explanation that requires further study is that 13- to 15-year-olds might be less influenced by their peers than older teenagers are. The importance of physical appearance was linked to communication patterns among teenagers. Teenagers commented on the importance of nice clothes and styled hair. The emphasis on appearance among teenagers is not new. Participants did discuss the possible connection between teenagers not talking about personal health issues with friends and the importance of how they appear to their peers.

The study used a theoretical framework for questions to participants. Use of the TPB increased the breadth of data collected. Specifically, themes relating to perceived control were identified, and this issue might not have been discovered without use of the TPB. Results relating to perceived control suggest that teenagers do not know how to arrange appointments on their own, that doctors’ visits take too much time, and that many teenagers require their parents to drive them to clinics.

Our results have several implications for clinical practice. It was clear that family physicians should speak to adolescents themselves, rather than to their parents. Asking parents to leave the room might increase physicians’ ability to communicate with teenaged patients. Family physicians might also ask adolescents for permission before asking about lifestyle, since teenagers might be unclear why these questions are relevant to their current health concerns. Other strategies for improving teenagers’ satisfaction with visits to doctors include providing appropriate reading material and attempting to avoid long waiting times.

Another finding that has clinical implications is the influence of parents on their teenage children. Our results suggest that parental influence is a strong motivator for young teenagers. For this reason, parents should be encouraged to arrange annual checkups for their adolescents and to foster development of relationships between adolescents and their physicians.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is that the adolescents participating in the study might not represent the general range of socioeconomic status (SES). We did not ask about participants’ SES due to the possibility of collecting inaccurate information and of discouraging participation. We tried to recruit adolescents from both higher and lower SES, but were unsuccessful in recruiting from targeted sources, such as schools and local community groups. Recruitment was successful through one medical clinic and one organized youth group. The clinic is located near downtown Edmonton and serves inner-city residents (lower SES) and university students and teachers (higher SES). The youth group is likely composed of those at higher SES.

Another limitation was the number of participants. We planned to recruit 30 to 40 adolescents, but were unable to enrol that many participants. Despite these limitations, the study provides new information on adolescents’ decision making in relation to primary health care. Strengths of the investigation include recruitment of both male and female adolescents, recruitment of teenagers who did and did not have checkups, rigorous data analysis, and use of a validation focus group to confirm and extend findings from the main study.

Conclusion

The long-term health consequences of behaviour that puts Canada’s adolescents’ health at risk are immense. Family physicians should recognize adolescents’ attitudes to health care and realize the potential barriers when trying to encourage these adolescents to attend their offices. By doing this, trips to doctors’ offices for periodic checkups could become more comfortable and beneficial for adolescents and less like, as one participant stated, a “trip to the zoo.”

Biography

Dr Klein, a family physician in Edmonton, Alta, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Assistant Director of CME at the University of Alberta. Dr Wild and Dr Cave teach in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Alberta.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Population Fund. The reproductive health of adolescents: a strategy for action. Geneva, Switz: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Canada. The opportunity of adolescence: the health sector contribution. Ottawa, Ont: Health Canada; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedberg VA, Bracken AC, Stashwick CA. Long-term consequences of adolescent health behaviours: implications for adolescent health services. Adolesc Med. 1999;10(1):137–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein D. Short report: Adolescents’ health. Does having a family physician make a difference? Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1000–1002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker ZA, Townsend J. The role of general practice in promoting teenage health: a review of the literature. Fam Pract. 1999;16(2):164–172. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rathe R. The complete physical. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(7):1439. 1439,1443-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz A. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Annual checkups revisited. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1637–1638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obeler SK, LaForce FM. The periodic physical examination in asymptomatic adults. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(3):214–226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-3-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker ZA, Oakley LL, Townsend JL. Evaluating the impact of primary care consultations on teenage lifestyle: a pilot study. Methods Inf Med. 2000;39(3):260–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The periodic health examination. CMAJ. 1979;121(9):1193–1254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Canadian guide to clinical preventive health care. Ottawa, Ont: Health Canada; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elster AB, Kuzsets NJ. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent preventive services (GAPS). Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for pediatric preventative health care. Pediatrics. 1995;96:373–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Canada. Statistical report on the health of Canadians. Ottawa, Ont: Health Canada; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oandasan I, Malik R. What do adolescent girls experience when they visit family practitioners? Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:2413–2420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. Chap 50, p. 179-211. San Diego, Calif: Elsevier; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Prom. 1996;11(2):87–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I. Models of human social behaviour and their application to health psychology. Psychol Health. 1998;13:735–739. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark NM, Becker MH. Theoretical model and strategies for improving adherence and disease management. In: Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK, McBee WL, editors. The handbook of health behaviour change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1998. pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothe JP. Undertaking qualitative research. Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wild TC, Kuiken D. Aesthetic attitude and variations in reported experience of a painting. Emp Stud Arts. 1992;10:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginsburg KR, Slap GB, Cnaan A, Forke CM, Balsley CM, Rouselle DM. Adolescents’ perceptions of factors affecting their decisions to seek health care. JAMA. 1995;273:1913–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steven ID, Thomas SA, Eckerman E, Browning C, Dickens E. A patient-determined general practice satisfaction questionnaire. Aust Fam Physician. 1999;28(4):342–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gribben B. Satisfaction with access to general practitioner services in South Auckland. N Z Med J. 1993;106(962):360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gribben B. Do access factors affect utilisation of general practitioner services in South Auckland? N Z Med J. 1992;105(945):453–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kassem NO, Lee JW, Modeste NN, Johnston PK. Understanding soft-drink consumption among female adolescents using the theory of planned behavior. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(3):278–291. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]