Abstract

PROBLEM BEING ADDRESSED

Nutrition services can have an important role in prevention and management of many conditions seen by family physicians, but access to these services in primary care is limited.

OBJECTIVE OF PROGRAM

To integrate specialized nutrition services into the offices of family physicians in Hamilton, Ont, in order to improve patient access to those services, to expand the range of problems seen in primary care, and to increase collaboration between family physicians and registered dietitians.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Registered dietitians were integrated into the offices of 80 family physicians. In collaboration with physicians, they assessed, treated, and consulted on a variety of nutrition-related problems. A central management team coordinated the dietitians’ activities.

CONCLUSION

Registered dietitians can augment and complement family physicians’ activities in preventing, assessing, and treating nutrition-related problems. This model of shared care can be applied to integrating other specialized services into primary care practices.

Abstract

PROBLÈME À L’ÉTUDE

Les services nutritionnels peuvent jouer un rôle important dans la prévention et le traitement de plusieurs conditions rencontrées par le médecin de famille, mais ces services sont peu accessibles dans les soins primaires.

OBJECTIF DU PROGRAMME

Intégrer des services nutritionnels spécialisés dans les cabinets de médecins de famille d’Hamilton (Ont.) pour en faciliter l’accès pour les patients, élargir le spectre des problèmes vus dans les soins primaires et promouvoir la collaboration entre médecins de famille et diététistes diplômés.

DESCRIPTION DU PROGRAMME

Des diététistes diplômés ont été intégrés dans les cabinets de 80 médecins de famille. En collaboration avec les médecins, ils ont évalué et traité différents problèmes d’ordre nutritionnel et ont prodigué des conseils. Une équipe centrale de gestion assurait la coordination des activités des diététistes.

CONCLUSION

Les diététistes peuvent élargir et compléter les activités des médecins de famille en prévenant, évaluant et traitant les problèmes d’ordre nutritionnel. Ce modèle de soins partagés pourrait s’appliquer à d’autres services spécialisés susceptibles d’être intégrés dans les soins primaires.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Many chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity, benefit from dietary counseling, but family doctors rarely have the time or expertise to counsel patients on nutrition.

An innovative collaborative model that integrated registered dietitians’ services into family practices was developed in Hamilton, Ont. Registered dietitians regularly visited family practices for consultations with both patients and physicians.

Patients had better access to dietary services provided in familiar settings and family doctors learned about dietary counseling through direct feedback from dietitians.

Patients, dietitians, and family physicians reported great satisfaction with this model.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Plusieurs conditions chroniques comme le diabète, les dyslipidémies et l’obésité nécessiteraient des conseils nutritionnels, mais le médecin de famille a rarement le temps ou l’expertise pour donner ce type de conseils.

Un modèle nouveau dans lequel des diététistes diplômés ont été intégrés dans les cabinets de médecins de famille a été développé à Hamilton. Par des visites régulières à ces cabinets, les diététistes ont pu répondre aux questions des patients comme à celles des médecins.

Le contexte familier a permis un meilleur accès des patients aux services nutritionnels et, au contact des diététistes, les médecins de famille ont appris à mieux conseiller les patients sur leur alimentation.

Patients, diététistes et médecins de famille se sont déclarés enchantés de ce modèle.

Nutrition plays an important role in prevention and management of many leading causes of morbidity and mortality1 seen in primary care, such as cardiovascular disease,2 diabetes,3 and obesity.4 Canadian family physicians receive relatively little training in the fundamentals of nutrition during medical school,5 have time constraints,6 and are presented with a vast amount of new information every year7; all these factors hinder them from providing effective dietary counseling. Registered dietitians have specialized skills, knowledge, and training in the area of food and nutrition,8 yet only 16.6% of Canadian family physicians whose main practice settings are private offices, private clinics, community clinics, or community health centres indicate that they have dietitians or nutritionists on staff.9

Objectives of the program

This paper describes a nutrition program in Hamilton, Ont, the Hamilton Health Service Organization Nutrition Program (HHSONP), that has successfully integrated registered dietitians into the offices of 80 family physicians. The program is based on a model of shared care: dietitians and family physicians work together to care for patients. Each practitioner provides services according to his or her skills and patients’ needs.

The program has four main goals:

to increase primary care patients’ access to nutrition services,

to expand the range of nutrition services (preventive and treatment) available in primary care,

to strengthen links between primary care and hospital and community nutrition programs, and

to increase family physicians’ knowledge of dietary principles and comfort with handling nutrition problems.

Program

The HHSONP, funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, began operating in 1994. The program was initially administered by a local hospital, but in 2000, it was amalgamated with the Hamilton-Wentworth HSO Mental Health Program (HHSOMHP) to form the Hamilton HSO Mental Health and Nutrition Program (HHSOMHNP).

The program includes 80 family physicians at 50 different sites across Hamilton, a city of 491 000 people in southern Ontario. Participating physicians are in rostered family medicine practices and are paid through a capitation system, rather than through fee-for-service. All were formerly working in health service organizations, and most are now in family health or primary care networks.

A registered dietitian visits each participating practice regularly. Currently, nine dietitians fill 6.0 full-time equivalent positions. Each physician receives about 10 hours of nutrition services per month, about half a day each week. In a four-physician practice, for example, a dietitian would be present for 2 days each week. One dietitian might be responsible for serving several practices. Practices are grouped geographically to reduce travel time for dietitians.

Within practices, registered dietitians provide assessments or consult with family physicians on nutrition-related problems. There are no specific referral criteria, and patients of all ages are served. To initiate assessment and treatment, family physicians complete referral forms. Patients are usually seen by a dietitian within 2 weeks of referral. Urgent referrals are identified and prioritized by dietitians. Dietitians have access to patients’ charts and can review bloodwork, previous treatments, and medical reports before assessments. Dietitians can discuss referrals with family physicians before assessments to collect additional information on presenting problems. Specific goals are identified for each patient and are reviewed at regular intervals.

A central management team responsible for coordinating the program hires the dietitians; assigns them to family physicians’ practices; and coordinates program development, implementation, and evaluation.

Activities of registered dietitians

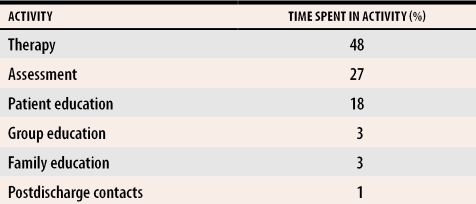

Registered dietitians spent 74% of their time in direct and indirect clinical activity, 19% in administration, 5% in personal educational activities and professional development, and 2% in other program-related activities. Direct clinical activity includes assessment, treatment plans, therapeutic intervention, group work, patient and family education, and postdischarge contacts (Table 1). Indirect clinical activity includes case review and discussion, charting, and referral to other services.

Table 1.

Time spent by registered dietitians in direct clinical activities

During the last 2 years, there has been a shift from individual counseling to educational group classes for commonly encountered problems, such as dyslipidemia and weight management. If necessary, individual follow up is arranged upon completion of group sessions. Topics covered in groups are similar to those that would be covered in individual counseling, and services can be delivered more efficiently in group sessions. Dietitians enter their weekly activities and case lists into hand-held computers that are downloaded monthly into the centralized database.

Collaboration with family physicians.

In the shared care model, family physicians and dietitians are both actively involved in care of patients, with regular opportunities for case discussion and review. In addition, the dietitians are readily available to provide advice or assistance that can be generalized to other patients, to answer nutrition-related questions, and to follow up on patients seen previously. This model of physician education is case based, brief, and easily incorporated into a family physician’s busy schedule. Dietitians also work closely with family physicians to develop practice-specific activities that enhance patient care, such as a callback system to monitor the progress of patients with dyslipidemia.

Preventive programs.

Integrating registered dietitians into primary care provides the opportunity to intervene at an early stage with those at risk of developing nutrition-related problems. For example, one of the program’s priorities has been identifying and preventing childhood obesity. Currently, the program is pilot-testing a project that involves measuring body mass index (BMI) of children and adolescents, administering a questionnaire on their dietary habits and physical activity, and offering a recommendation on a prescription form.

Registered dietitians’ other activities.

The dietitians and central management team meet monthly to address issues, learn from each other’s experiences, share resources, and participate in educational activities. They also collaborate on activities, such as evaluating nutrition education materials and making them available in each practice, arranging educational groups for patients, developing and maintaining a resource library, and organizing professional development activities for the dietitians. This assists the central management team in shaping the direction and priorities of the program and in coordinating program resources.

Registered dietitians represent the program on community committees and organizations, such as the Hamilton Nutrition Committee, the Joint Dietetics Patient Education Committee, and the Dietitians of Canada Primary Health Care Action Group. This is an important way to establish and strengthen links between the HHSONP, which is primary care based, and nutrition programs that are hospital or community based and to share information and resources. Dietitians also serve as mentors for dietetic interns from both undergraduate and graduate nutrition programs, make presentations about the program at nutrition-related conferences, and participate in ongoing practice-based research.

Central management team

Activities in each practice are coordinated by a central management team responsible for allocation and distribution of funds, recruitment of dietitians, and evaluation of activities in each practice and in the program as a whole. The central management team develops, implements, and monitors program standards and maintains a centralized database. Team members provide regular clinical reports to family physicians, the registered dietitians, and the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Funding

The program is funded through a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Institutional Supplementary Program, which supplements capitation funding received by practices. While this model is still relatively uncommon in Canada, primary care reform, particularly in Ontario, is likely to see increasing numbers of practices receiving funding to incorporate nutrition services. Other funding options, such as seconding dietitians from hospital services, could be explored to adapt this model to fee-for-service practices.

Data collection

Family physicians complete a referral form for each patient referred to a registered dietitian, recording demographic information and identifying what they perceive to be the main reason for referral from a checklist of 30 commonly occurring problems. Dietitians complete treatment worksheets at time of first assessment and at completion of treatment. The worksheet uses standardized outcome measures to assess the effectiveness of interventions and treatments. These include clinical measures, such as weight, blood glucose, and blood pressure; dietary intake measures, such as calories, fibre, and fat; and lifestyle measures, such as changes in smoking habits, physical activity, and alcohol consumption.

One copy of each form is filed in the patient’s chart, and one is forwarded to the central management team for entry into a centralized database. To protect patient confidentiality, no identifying information leaves the practice. Data are entered into the database using a program referral number (from consecutively numbered nutrition referral forms) and a unique patient number. This number allows a longitudinal record to be compiled for patients who are referred more than once.

The program also collects data on consumer and provider satisfaction. The current data collection and evaluation process was initiated in 2000.

Evaluation

Referrals.

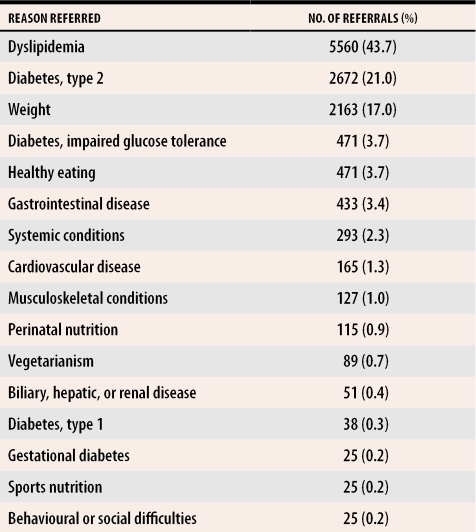

The program receives an average of 4280 nutrition referrals annually (710 per full-time-equivalent dietitian). An average of 4710 patients are seen each year, which includes cases carried over from previous years. Of patients referred, 45% are 45 to 64 years old, 28% are 18 to 44 years old, 23% are 65 years or older, and 4% are younger than 18 years; 56% are women, and 44% are men.

The most common reasons for referral include dyslipidemia (44% of all referrals), type 2 diabetes (21%), and obesity (17%) (Table 2). While these percentages have remained fairly constant since 2000, over the last 2 years the variety of problems referred to dietitians has increased.

Table 2.

Main reasons for referral 2000 to 2002

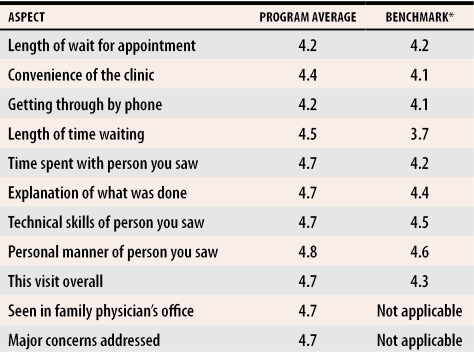

Patient satisfaction.

The Visit Satisfaction Questionnaire,10 a nine-item questionnaire using a five-point Likert scale, to which the program has added two items, is completed by patients at the end of their first visits with registered dietitians. Patients’ satisfaction with dietitians’ services has been consistently high (Table 3), meeting or exceeding Group Health of America benchmark criteria for all measured items.

Table 3. Summary of responses to questionnaire on satisfaction with dietitians’ services.

Scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1–very dissatisfied, 5–very satisfied), N = 1558.

*Group Health of America benchmark.

Provider satisfaction.

Clinicians involved in the program regularly complete satisfaction surveys. In the 2001 survey, family physicians stated that registered dietitians were easily integrated into their practices and that patients benefited greatly from dietitians’ services. Physicians said that working collaboratively with dietitians in their practices had increased their skills and comfort in handling nutrition issues and that they regarded registered dietitians as a useful educational resource. They also indicated that dietitians’ role in the practice was complementary to their own and that dietitians were valued members of health care teams.

The registered dietitians rated this style of practice very positively, expressing high levels of satisfaction with the model, particularly with their acceptance as members of family practice teams and as educational resources. They indicated they would recommend this type of practice to colleagues.

Discussion

The benefits of providing nutrition services through community- or hospital-based programs are well documented.11 There is also evidence in the literature of the benefits of collaboration between family physicians and providers of specialized services, such as mental health workers12,13 and pharmacists,14 in primary care. Programs like the HHSONP that integrate nutrition services into primary care are still relatively rare, although they are gaining increasing support.15,16

Dietitians working in other community settings, such as community health centres, are also engaged in health promotion; consumer education; and disease prevention, treatment, and management. The distinctive features and benefits of the HHSONP are linked to its objectives: increased access, expanded range of services, and enhanced collaboration between family physicians and registered dietitians.

Integrating registered dietitians into family physicians’ offices increases access to nutrition services and reduces waiting times. In particular, it increases access for underserved populations, such as members of ethnocultural communities who might be reluctant to visit traditional services, patients who cannot afford the cost of those services on a private basis, and patients who would otherwise be treated by their family physicians without referral to a specialized service. Patients are seen in a familiar, trusted, and convenient setting.

A collaborative approach broadens the range of nutrition-related problems addressed in primary care and allows a wider variety of services to be delivered. These include early detection, self-management strategies and support, innovative approaches to treatment, monitoring and reassessments, and linking with community resources. These are all components of comprehensive care for those with nutrition problems and are consistent with a chronic disease management model.17

Having registered dietitians in primary care improves the coordination of primary and specialized patient care. Communication is greatly improved, and there are frequent opportunities for case discussion and review. Treatment recommendations can be transmitted orally to family physicians following assessments and recorded in patients’ charts. This model also enhances continuity of care, as dietitians can be involved in patients’ care at any time, either by seeing patients again or by discussing care plans with family physicians.

The partnership between primary care providers and registered dietitians offers opportunities for physician education that is focused on patients, flexible, and easily adaptable to primary care. Dietitians can also assist family physicians in developing screening procedures to identify those at risk of developing specific problems, can regularly monitor progress through chart reviews, or, if necessary, can provide assessment and intervention. Such strategies are more likely to be effective if family physicians and dietitians are working collaboratively to develop appropriate materials and interventions.

While this approach allows a variety of nutrition-related problems to be managed successfully in primary care, specialized assessment and treatment will still be necessary for some patients. Integrated services in primary care should be seen as part of a continuum of care, with access to secondary and tertiary services often facilitated by dietitians.

Family physicians and dietitians might need to make adjustments when working collaboratively. It is important that they understand the skills and knowledge each can contribute to meeting the needs of their patients. Practical challenges cited by registered dietitians in the HHSONP include working at multiple sites and finding suitable space in family physicians’ offices to see patients, although practices have been responsive in creating space for the dietitians.

Conclusion

Registered dietitians working in primary care can augment and complement family physicians’ role in managing nutrition problems. They can assist with daily management of many common medical problems, increase access to nutrition services, reduce waiting times, and help increase family physicians’ skills and comfort in handling patients’ nutrition problems.

The HHSONP model has many of the components of a chronic disease management model and is likely to be increasingly relevant as nutrition and other specialized services are integrated into primary care as part of primary care reform. The model is very well received by patients and providers and is adaptable to any practice in any community.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the registered dietitians of the Hamilton Health Service Organization Nutrition Program: Susan Bird, Carol Clarke, Wendy Gamblen, Tracy Hussey, Melanie Kippen, Michele MacDonald Werstuck, Jennifer McGregor, Jacquelyn McKenzie, and Krista Rowell. We also thank Shelley Brown, Michele Mach, and Wanda Kelly for reviewing and analyzing program data and assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

Biography

Ms Crustolo is a Clinical Lecturer in the School of Nursing at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, and Manager of the Hamilton Health Service Organization (HSO) Mental Health & Nutrition Program. Dr Kates is a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences at McMaster University with a cross-appointment in the Department of Family Medicine. He is Director of the Hamilton HSO Mental Health and Nutrition Program. Ms Ackerman and Ms Schamehorn are on staff at the Hamilton HSO Mental Health and Nutrition Program.

References

- 1.American Dietetic Association. Hampl JS, Anderson JV, Mullis R. Position of the American Dietetic Association: the role of dietetics professionals in health promotion and disease prevention. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(11):1680–1687. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Hypertension Education Program. Touyz RM, Campbell N, Logan A, Gledhill N, Petrella R, Padwal R. The 2004 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: part III–lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20(1):55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association Task Force for Writing Nutrition Principles and Recommendations for the Management of Diabetes and Related Complications. American Diabetes Association position statement: evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Dietetic Association. Cummings S, Parham ES, Strain GW. Position of the American Dietetic Association: weight management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(8):1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosser WW. Nutritional advice in Canadian family practice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(4 Suppl):1011–1015. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.1011S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly SA, Joffres MR. Nutrition education practices and opinions of Alberta family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1990;36:53–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guideline Advisory Committee. Rosser WW, Davis D, Gilbart E. Assessing guidelines for use in family practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(11):969–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: integration of medical nutrition therapy and pharmacotherapy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(10):1363–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.College of Family Physicians of Canada. 2001 CFPC National Family Physician Workforce Survey [Part of the Janus Project: Family physicians meeting the needs of tomorrow’s society]. Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE., Jr Patients’ ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1993;270(7):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietitians of Canada, Community Dietitians in Health Centres Network. Community dietitians make a difference: make sure there is a dietitian on your team! Toronto, Ont: Dietitians of Canada, Community Dietitians in Health Centres Network; 1999. [cited 2005 August 10]. Available from: http://www.opha.on.ca/resources/dietitians.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kates N, Crustolo AM, Farrar S, Nikolaou L. Counsellors in primary care: benefits and lessons learned. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(9):857–862. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kates N, Crustolo AM, Farrar S, Nikolaou L, Ackerman S, Brown S. Mental health care and nutrition; integrating specialist services into primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1898–1903. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellors J, Sellors C, Woodward C, Dolovich L, Poston J, Trim K, et al. Expanded role of pharmacists consulting in family physicians’ offices—a highly acceptable program model. Can Pharm J. 2001;134(7):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietitians of Canada. The role of the registered dietitian in primary health care: a national perspective. Toronto, Ont: Dietitians of Canada; 2001. [cited 2005 August 10]. Available from: http://www.dietitians.ca/news/downloads/role_of_RD_in_PHC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brauer PM. Advocating for dietitian services in primary health care. Presentation at Community Dietitians in Health Centres Network Annual Conference; February 10, 2004, Ottawa, Ont.

- 17.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]