Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Many factors are at play in the process of clinical decision making, but to date, the interaction of these factors has not been well understood. Such information could have important implications for teaching and promoting evidence-based medicine (EBM) in primary care. This study was designed to explore the relationship between physician-related variables and management of patient-related contextual factors in clinical decision making. A secondary objective was to examine the extent to which this relationship varies by type of clinical decision.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional randomized postal survey of 1134 Canadian primary care physicians stratified by age, sex, and practice location. Nonrespondents were sent reminders at 4 weeks and again at 8 weeks; at 12 weeks, all remaining nonrespondents were mailed replacement copies of the questionnaire.

SETTING

Family practices in Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Of the final sample of 431 family physicians, 52% were men, 63% practised in urban locations, and 71% were in group practice.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Self-reported likelihood of considering various contextual factors during the course of clinical decision making.

RESULTS

Despite the three follow-up mailings, the final response rate was 42%; however, nonrespondents did not differ significantly from respondents on three important demographic factors: age, sex, and practice location. Using multinomial logistic regression analysis, the data showed that female family physicians and practitioners less strongly identified with EBM were more likely to consider contextual factors in clinical decision making. The effect was more obvious for ordering tests than for decisions about treatment.

CONCLUSION

The evolving model of EBM should consider important physician-related variables in clinical decision making. Our data indicate that physicians’ sex and identification with the tenets of EBM influence management of contextual factors. These results have important implications because they indicate that clinicians strongly identified with the EBM model of clinical practice are less sensitive to context, which might be an obstacle to efforts to integrate patient values and clinical circumstances into patient-centred care. We believe these findings support continued development of the model of “context-sensitive medicine” previously proposed as an alternative to EBM.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Plusieurs facteurs contribuent au processus de prise de décision clinique, mais à ce jour, les interactions entre ces facteurs demeurent mal comprises. Une telle information pourrait avoir d’importantes conséquences pour l’enseignement et la promotion d’une pratique médicale de première ligne fondée sur des preuves (PMFP). Cette étude avait pour but d’étudier comment les variables propres au médecin et les facteurs contextuels liés au traitement du patient interagissent pour influencer la prise de décision clinique. Un objectif secondaire était de vérifier à quel point ces interactions peuvent varier selon le type de décision clinique.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête postale transversale avec répartition aléatoire auprès de 1134 médecins canadiens de première ligne stratifiés en fonction de l’âge, du sexe et du lieu de pratique. Des rappels ont été postés aux non-répondants à 4 et à 8 semaines; un nouveau questionnaire a été adressé aux derniers non-répondants à 12 semaines.

CONTEXTE

Établissements de pratique familiale au Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Parmi les 431 médecins de famille de l’échantillon final, 52% étaient des hommes, 63% pratiquaient en milieu urbain et 71% pratiquaient en groupe.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

La probabilité de tenir compte de divers facteurs contextuels au moment de la prise de décision clinique, telle que rapportée par les participants.

RÉSULTATS

Malgré l’envoi de trois rappel, le taux de réponse final n’était que de 42%; toutefois, les non-répondants ne différaient pas significativement des répondants sur trois indices démographiques importants: âge, sexe et lieu de pratique. L’analyse des données par régression logistique multiple a montré que les médecins de famille féminins et les praticiens qui avaient moins d’intérêt pour la PMFP avaient davantage tendance à tenir compte des facteurs contextuels dans la prise de décision clinique. Cette tendance était plus évidente dans les demandes d’examens que dans les choix de traitement.

CONCLUSION

Le modèle changeant de PMFP devrait tenir compte des importants facteurs propres au médecin qui influencent la prise de décision clinique. Les présentes données indiquent que le sexe du médecin et son adhérence aux principes de la PMFP influencent la prise en considération des facteurs contextuels. Ces résultats ont des conséquences importantes parce qu’ils suggèrent que les médecins qui adhèrent fermement au modèle de PMFP sont moins sensibles aux facteurs contextuels, ce qui pourrait nuire aux efforts visant à intégrer les valeurs du patient et les circonstances cliniques dans les soins centrés sur le patient. Les présentes données soulignent l’importance de poursuivre le développement du modèle de «médecine sensible au contexte» antérieurement proposé comme alternative à la PMFP.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Critics of evidence-based medicine (EBM) argue that professional experience, intuition, and context have been devalued. In response, EBM now attempts to integrate context and patient preferences with best evidence for making clinical decisions.

This study found that women physicians and family physicians who were less identified with EBM were more likely to be influenced by contextual variables than physicians strongly identified with EBM were.

Ironically, family physicians who were less identified with EBM might, in fact, be practising closer to the revised model of EBM that takes clinical context and patient preferences into account.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Les critiques de la pratique médicale fondée sur des preuves (PMFP) prétendent qu’elle minimise l’importance de l’expérience, de l’intuition et du contexte. En réponse, la PMFP tente maintenant de concilier préférences du patient, contexte et données probantes dans la prise de décision clinique.

Cette étude a montré que les femmes médecins et les médecins de famille qui n’adhéraient pas beaucoup à la PMFP tiennent plus volontiers compte des variables contextuelles que les médecins qui adhérent fermement à PMFP.

Assez curieusement, les médecins de famille qui adhérent le moins aux principes de la PMFP pourraient en réalité avoir une pratique se rapprochant davantage du modèle révisé de PMFP, lequel tient compte du contexte clinique et des préférences du patient.

Following publication of the seminal paper in 1992,1 the effect of evidence-based medicine (EBM) on delivery of health care has been vast, yet not without controversy. Proponents of EBM stress the need to consider research evidence in the delivery of patient care.2 As a result, other means of justifying decisions, such as professional experience, clinical intuition, and physiologic rationale, have been relegated to subordinate roles.3-6

Some commentators have been critical of the EBM model. Greenhalgh and Worrall, for example, have argued that “medical practice simply does not fit the model in which clinical encounters are reduced to unidimensional problems and neatly solved by recourse to research trials and the hierarchy of evidence.”7 Others have expressed concern that little consideration is accorded patient values and preferences8,9 and that there is a gap between empirical evidence and clinical practice.5 The important role that context plays in clinical decision making is now being explored.10,11 There is growing acknowledgment (both tacit and overt) that just as critical as identifying the best available evidence is understanding how to apply that evidence in the specific context of care informed by clinical experience and expertise.12,13

Currently, our understanding of how evidence is applied in family practice is extremely limited. For instance, the association between physician-related factors and practising EBM has remained largely unexplored, despite substantial evidence that these factors can influence clinical practice. Studies have indicated that female practitioners tend to spend more time with patients,14 engage in more patient-centred communication,15 employ more preventive strategies,16 and exhibit a more egalitarian style that is reflected in increased levels of patient participation.17 It remains unclear, however, whether the sex of a physician is related to his or her propensity to practise EBM.

A multitude of contextual factors and forces are at play in primary care.10,12 In response to critics, the proponents of EBM now place considerably greater emphasis on the need to consider these factors and forces along with the findings of scientific research.18,19 In the most recent conceptualization, “clinical state and circumstances” and “patient preferences and actions” are integrated with the best available research evidence. According to the model, “clinical expertise is needed to bring these considerations together and recommend the treatment that the patient is agreeable to accepting.”18 While a great advance over previous versions, the revised model fails to incorporate numerous physician-related variables that have been shown to influence clinical decision making.

Given this limitation of the EBM model, this study investigates the influence of two major sets of contextual factors on clinical decision making. Patient-related contextual factors include the typical demographic variables (eg, age, sex, ethnicity, and religion) and medical and psychosocial variables, such as comorbidity, trust in the physician, and preferences and expectations regarding treatment. This first set of contexual factors encompasses “patient preferences and actions” and “clinical state and circumstances” as described in the revised model of evidence-based decision making.

Physician-related contextual factors include typical demographic variables, such as physicians’ age, sex, and years in practice, and a variety of salient practice-related variables (eg, number of patients seen each week, practice location). To date, the interaction of these factors in the clinical context has not been investigated; this type of information could have important implications for teaching and promoting EBM in primary care. The main objective of this study was to explore the relationship between physician-related variables and management of patient-related contextual factors in clinical decision making. A secondary objective was to examine the extent to which this relationship varies by type of clinical decision (ie, ordering tests, prescribing).

METHODS

Participants and setting

This paper reports on the quantitative component of a larger multimethod research project based in the Primary Care Research Unit at Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ont. In spring 2002, we conducted a mailed survey of a cross section of primary care physicians across Canada. The sampling frame, which was provided by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), comprised a computer-generated random list of 1134 family physicians. Inclusion criteria were that physicians be Certificants of the CFPC and in active practice at the time of study. The sample was stratified by age, sex, and urban-rural composition of the CFPC membership (approximately 16 000 members nationwide). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was a four-page questionnaire with four main sections. Content and design of the survey were refined on the basis of pilot-testing with a small group of primary care physicians and health services researchers. The first section comprised 10 Likert-type items measuring physicians’ attitudes toward the practice of EBM in primary care. These 10 items were adapted from a British survey of general practitioners20; we developed the remainder of the questionnaire for the purposes of this study.

The second section listed 12 distinct contextual factors. Respondents were asked to indicate the likelihood that each would influence their decisions to order diagnostic tests and prescribe clinical treatments. Items in the list of contextual factors corresponded to key components of the recently revised model of evidence-based clinical decision making.18 For instance, items such as patients’ age, ethnicity, and comorbidity represented the “clinical state and circumstances” component of the model; an item worded “an expectation to receive test/treatment” was included to elicit patient preferences and actions.

In the third section of the questionnaire, respondents were presented with a forced-choice option in four simulated clinical scenarios or case vignettes (results reported separately21). The final section asked respondents to supply typical demographic information.

Data collection and analysis

To ensure stable estimates in logistic regression analysis, a minimum of 15 data points per predictor is preferred.22 Assuming a response rate of approximately 50%, we estimated that no fewer than 400 completed questionnaires would be required; on this basis, the survey package was initially mailed to 1134 family physicians. Along with the questionnaire, the package contained a personalized cover letter, a stamped return envelope, and a reply postcard. Inclusion of the latter was necessitated by the fact that no identifying marks appeared on the questionnaire itself; reply postcards were to be returned separately from the questionnaire in order to indicate intentions regarding participation in the study. Nonrespondents were sent reminders at 4 weeks and again at 8 weeks. At 12 weeks, remaining nonrespondents received a second letter accompanied by a replacement copy of the questionnaire.

Data were entered into a spreadsheet for statistical analysis using SAS 8.2. Descriptive data are reported as percentages of the overall total. Fisher exact test was used to compare respondents with nonrespondents. For the variable “self-identification with EBM,” we categorized respondents as “Strongly Self-identified with EBM” (SS-EBM practitioner: 80% or greater clinical practice self-defined as evidence based [99 physicians, 24%]), “Weakly Self-identified with EBM” (WS-EBM practitioner: 40% or less clinical practice self-defined as evidence based [136 physicians, 33%]), or “Neutral” (60% of clinical practice self-defined as evidence based [177 physicians, 43%]).

Both bivariate and multivariate techniques were used. Before proceeding with the regression analysis, bivariate analyses were performed to identify potential explanatory variables for the two outcomes of interest: influence on ordering tests and influence on treatment decisions. From a large number of variables, two potential predictors emerged: physicians’ sex and self-identification with EBM. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was then used to assess the strength of association between these potential predictors and the outcome variables, while adjusting for all remaining variables. Main effects are reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and P values. Odds ratios reported are the odds of Likely/Very Likely versus Unlikely/Very Unlikely (we do not report the odds of Neutral versus Unlikely/Very Unlikely). Finally, paired-sample t tests were used to identify significant differences in the influence of contextual factors on ordering tests versus treatment decisions. Statistical significance was set at P <.05 and 95% confidence intervals excluding the null value (1.00).

RESULTS

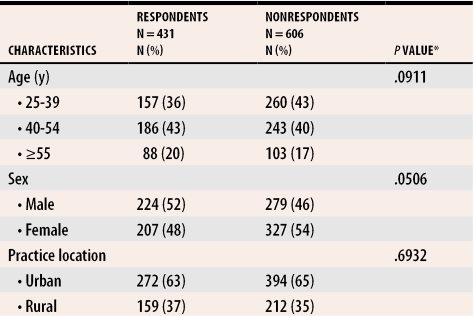

Of the 1134 family physicians in the original target sample, 97 were excluded: 63 were no longer practising family medicine, 23 had moved (incorrect mailing address), and 11 were either retired or on leave of absence. Of the remaining 1037, 431 (42%) completed and returned questionnaires. Table 1 compares respondents with nonrespondents. Results of Fisher exact test indicate that nonrespondents did not differ significantly from respondents with respect to the important variables of age, sex, and practice location (thereby minimizing the problem of nonresponse bias). Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the final sample.

Table 1.

Comparison of respondents and nonrespondents

Percentages might not add to 100 due to rounding.

*Using Fisher exact test.

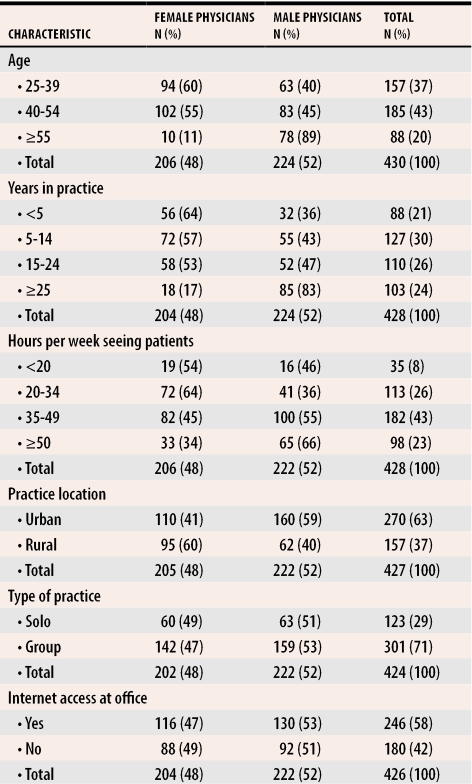

Table 2.

Demographic profile of survey respondents

Percentages might not add to 100 due to rounding.

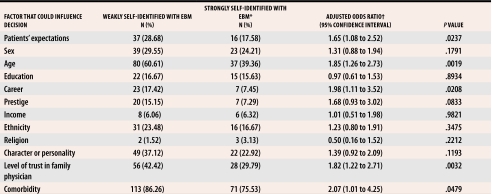

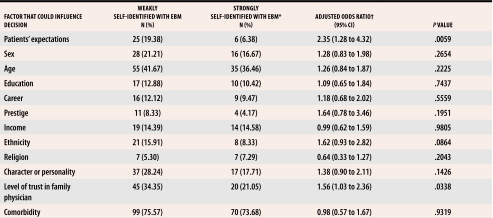

Contextual factors influencing ordering of tests

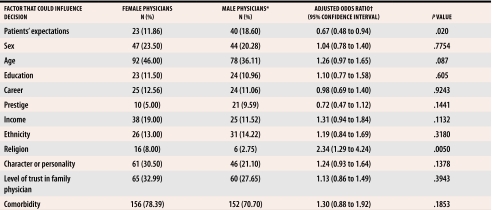

Multinomial logistic regression analysis indicated that, with respect to test ordering, WS-EBM practitioners were more likely to report being influenced by patients’ expectations, age, career, level of trust, and comorbidity than SS-EBM practitioners were (Table 3). Also, female physicians were more likely than male physicians to report considering patients’ age and religion when deciding whether to order tests (Table 4).

Table 3. Contextual factors that could influence the decision to order a particular diagnostic test by physicians’ self-identification with EBM practice.

Some surveys were missing data.

EBM—evidence-based medicine.

*Used as baseline comparison.

†Adjusted for physicians’ age, sex, years in practice, hours per week seeing patients, practice location, and Internet access.

Table 4. Contextual factors that could influence the decision to order a particular diagnostic test by whether a physician was male or female.

Some surveys were missing data.

*Used as baseline comparison.

†Adjusted for physicians’ age, sex, years in practice, hours per week seeing patients, practice location, and Internet access.

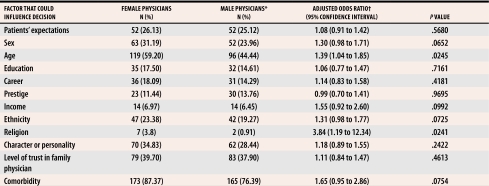

Contextual factors influencing treatment decisions

Regarding treatment decisions, WS-EBM practitioners were more likely to report being influenced by patient expectations and level of trust than SS-EBM practitioners were (Table 5). Also, male physicians were more likely than female physicians to report that they consider patients’ expectations when making decisions about treatment; female physicians were more likely to report considering a patient’s religion (Table 6).

Table 5. Contextual factors that could influence the decision to prescribe a particular treatment by physicians’ self-identification with EBM.

Some surveys were missing data.

EBM—evidence-based medicine.

*Used as baseline comparison.

†Adjusted for physicians’ age, sex, years in practice, hours per week seeing patients, practice location, and Internet access.

Table 6. Contextual factors that could influence the decision to prescribe a particular treatment by whether a physician was male or female.

Some surveys were missing data.

*Used as baseline comparison.†Adjusted for physicians’ age, sex, years in practice, hours per week seeing patients, practice location, and Internet access.

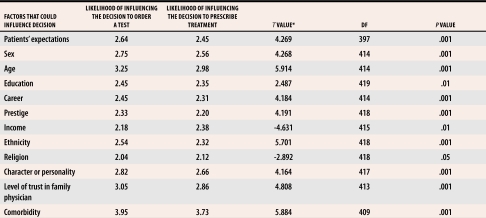

Ordering tests compared with prescribing

A comparison of means indicated significant differences in the influence of contextual factors on ordering tests and on treatment decisions. As shown in Table 7, contextual factors were more likely to be considered in decisions regarding diagnostic tests than in decisions about treatment. The two exceptions to this pattern were patients’ income and religion, both of which exerted a greater influence on treatment decisions.

Table 7. Comparison of means for ordering tests versus treatment decisions.

Likelihood of influence was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale where 1—very unlikely and 5—very likely to influence decision making.

*Using paired-samples t test.

DISCUSSION

Research evidence, clinical context, and patients’ values and preferences interact in the daily course of clinical decision making. Results of this study suggest that female family physicians and practitioners less strongly identified with EBM are more likely to consider contextual factors when making clinical decisions. The effect is more obvious on ordering tests than on treatment decisions. These results are important for the changing nature of EBM becauses they indicate that clinicians strongly identified with EBM are less sensitive to context, which might hinder efforts to integrate patients’ values and circumstances into a model of evidence-based care. Ironically, those less identified with EBM in our study might, in fact, be practising closer to the revised model of evidence-based practice currently being promoted.18

Physician-related factors

To our knowledge, no study has examined the influence of context on clinical decision making using a measure of physicians’ self-reported identification with EBM. Our findings suggest that family physicians who are less identified with EBM tend to be more influenced by contextual variables relating to patient factors, such as comorbidity and age. Our data also show that female family physicians are more likely to consider contextual factors than male physicians are, which is in accordance with previous studies demonstrating that female physicians tend to respond more to contextual clues, spend more time with patients, and engage in more communication that could be considered patient centred than their male colleagues.14,15 The results add to our current understanding and interpretation of EBM in primary care. Those who advocate for and promote practising EBM in primary care might need to be more sensitive to differences in the way male and female physicians practise.

Ordering tests compared with prescribing

Another observation in this study is the difference in influence of contextual factors on ordering tests and prescribing. With the exception of religion and income, physicians in this sample were more likely to consider contextual factors when ordering diagnostic tests than when prescribing treatments. While the differences are statistically significant, the meaning is unclear because absolute differences are small (no difference exceeding 1 on our Likert scale). The pattern of results suggests subtle differences in how contextual factors are managed in clinical practice. The results are consistent with a recent study demonstrating the strong influence of patients’ requests for clinical services on physicians’ behaviour. In a study where patients’ requests were recorded, the authors concluded that such requests are extremely frequent and substantially alter physicians’ behaviour, which results in increased use of diagnostic tests and prescriptions.23

Implications

By showing how physician-related factors influence clinical decision making, our findings make an important contribution to the continuing evolution of EBM. Given the widespread adoption and promotion of the EBM approach to teaching and practice of clinical medicine, we believe these results lend support to continued development of the model of “context-sensitive medicine” previously proposed as an alternative to EBM.7 Recent revisions to the original model of EBM have indicated the pressing need to account for patient preferences and values as legitimate influences in clinical decision making and in how systems are designed.

This is especially intriguing for primary care, in view of the criticism of EBM as unsuitable for the diversity, ambiguity, and uncertainty inherent in family medicine.10,12 The results are also consistent with a recent empirical study of Canadian family physicians’ perspectives on evidence-based cardiac care. That study demonstrated how contextual factors, such as trust between physician and patient, between physician and evidence source, and physicians’ trust in institutions, mediate whether physicians take up evidence-based practice. The authors recommend further empirical work examining the influence of relational issues on evidence-based practice.24

Limitations

This study is based on a stratified random sample of Canadian family physicians, all of whom are CFPC Certificants. Because our sample was composed exclusively of College members, our data might not reflect the practices of general practitioners who are not certified by the CFPC and who are, therefore, not obligated to participate in the continuing medical education mandatory for CFPC members.

Second, despite three mailings, the final response rate was only 42%. As reported above, however, nonrespondents did not differ significantly from respondents in three important factors: age, sex, and practice location. While low response rate is an important potential source of bias in survey research, a low response rate does not necessarily degrade the validity of the data25: sampling bias can be predicted, tested for, and corrected.26 Also, it is worth noting that high response rates are less important for homogeneous samples responding as members of a professional group on matters of concern to them (such as with physicians surveyed on medical care issues) than for heterogeneous samples responding as individuals.27 We acknowledge the possibility that nonrespondents could differ from respondents with respect to, for instance, degree of reflexivity in clinical practice or model of medical training program. A final limitation is that our results rely on self-reports without confirmation from actual practice.

Conclusion

The findings of this cross-sectional study of a random sample of Canadian family physicians suggest variability in the influence of contextual factors on clinical decision making. Physicians weakly self-identified with EBM were more likely to consider contextual factors when making decisions than those strongly identified with EBM. Also, female physicians were more likely to be influenced by context than male physicians were. Further studies exploring differences between women and men in perception of the use and importance of EBM, as well as differences between effects on diagnosis and treatment, are needed.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to our anonymous reviewers who commented on an earlier version of this paper. Special thanks to Sabrina Prevedel at the College of Family Physicians of Canada for her assistance with the sampling frame. Errol Colak contributed to the layout and design of the questionnaire; Jason Nie and Erica Zarkovich assisted with mailing out the questionnaires and data entry; and Shari Gruman formatted the manuscript. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge all of the busy family physicians who voluntarily participated in our survey.

This research was supported by HEALNet (Health Evidence Applications and Linkage Network), a member of the Networks of Centres of Excellence program, which is a unique partnership among Canadian universities, Industry Canada, and the federal research granting councils (1995-2002). Dr Upshur is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Research Scholar Award from the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Biographies

Mr Tracy is a Research Associate in the Primary Care Research Unit at Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre (SWCHSC) in Toronto, Ont.

Dr Dantas was a Research Associate in the Primary Care Research Unit at SWCHSC at the time of this research.

Dr Moineddin is a biostatistician in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr Upshur is Director of the Primary Care Research Unit at SWCHSC and an Associate Professor in the Departments of Family and Community Medicine and Public Health Sciences at the University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straus SE, Sackett DL. Getting research findings into practice: using research findings in clinical practice. BMJ. 1998;317:339–342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh I, Lyons M. Evidence-based care and the case for intuition and tacit knowledge in clinical assessment and decision making in mental health nursing practice: an empirical contribution to the debate. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):397–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonelli MR. The limits of evidence-based medicine. Respir Care. 2001;46(12):1435–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlton BG, Miles A. The rise and fall of EBM. Q J Med. 1998;91(5):371–374. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh T, Worrall JG. From EBM to CSM: the evolution of context-sensitive medicine. J Eval Clin Pract. 1997;3(2):105–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubenfeld GD. Understanding why we agree on the evidence but disagree on the medicine. Respir Care. 2001;46(12):1442–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upshur RE. If not evidence, then what? Or does medicine really need a base? J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(2):113–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2002.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tracy CS, Dantas GC, Upshur RE. Evidence-based medicine in primary care: qualitative study of family physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur RE. Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(1):207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosser WW. Application of evidence from randomised controlled trials to general practice. Lancet. 1999;353(9153):661–664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09103-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macnaughton RJ. Evidence and clinical judgment. J Eval Clin Pract. 1998;4(2):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bensing JM, van den Brink-Muinen A, de Bakker DH. Gender differences in practice style: a Dutch study of general practitioners. Med Care. 1993;31(3):219–229. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002;288(6):756–764. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lurie N, Margolis KL, McGovern PG, Mink PJ, Slater JS. Why do patients of female physicians have higher rates of breast and cervical cancer screening? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):34–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.12102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JA, Roter DL. Medical communication and gender: a summary of research. J Gend Specif Med. 1998;1(2):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Physicians’ and patients’ choices in evidence based practice. BMJ. 2002;324:1350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straus SE. Individualizing treatment decisions: the likelihood of being helped or harmed. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25(2):210–224. doi: 10.1177/016327870202500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioners’ perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:361–365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tracy CS, Dantas GC, Moineddin R, Upshur RE. The nexus of evidence, context, and patient preferences in primary care: postal survey of Canadian family physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Azari R, Kelly-Reif S, Krupat E, Thom D. Direct observation of requests for clinical services in office practice: what do patients want and do they get it? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1673–1681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson LA, Putnam W, Twohig PL, Burge F, Nicol K, Cox JL. What has trust got to do with it? Cardiac risk reduction and family physicians’ discussions of evidence-based recommendations. Health Risk Soc. 2004;6:239–255. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Templeton L, Deehan A, Taylor C, Drummond C, Strang J. Surveying general practitioners: does a low response rate matter? Br J Gen Pract. pp. 91–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Barclay S, Todd C, Finlay I, Grande G, Wyatt P. Not another questionnaire! Maximizing the response rate, predicting non-response and assessing non-response bias in postal questionnaire studies of GPs. Fam Pract. 2002;19:105–111. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobal J, Ferentz KS. Comparing physicians’ responses to the first and second mailings of a questionnaire. Eval Health Prof. 1989;12(3):329–339. [Google Scholar]