Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate whether family physicians thought they could use cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in their practices, and if so, how, and to discover what the barriers to implementation might be.

DESIGN

Qualitative study using taped interviews.

SETTING

British Columbia and Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Physicians practising family medicine in a variety of settings who attended an educational session on CBT.

METHOD

Six months after participating in a 5-hour seminar on CBT, consenting physicians were interviewed to determine their experiences with using CBT in their practices. The interviews used a semistructured guide and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The constant comparative method of data analysis was used to identify key words and themes.

MAIN FINDINGS

Most participants (34 of 42) reported using elements of CBT in their practices. Barriers mentioned by physicians to offering CBT to patients were lack of time, practice distractions and interruptions, and the perception that some patients were not good candidates for CBT. Barriers to patients’ accepting or using CBT were preferences for pharmacotherapy and lack of motivation or interest. Physicians could overcome some barriers by using CBT’s structure; this reduced the amount of in-office time required and helped them cope with interruptions. They selected specific CBT methods that fit their practices and patients.

CONCLUSION

Most participants saw CBT as a useful part of practice and reported implementing it successfully. There were, however, barriers to implementation in primary care. These barriers need to be addressed if CBT is to be taught to primary care physicians and offered in their practices.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer si les médecins de famille se sentent capables d’utiliser la thérapie cognitivo-comportementale (TCC) dans leur pratique et comment ils pourraient éventuellement le faire, et vérifier les obstacles à la mise en œuvre de cette technique.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Étude qualitative à l’aide d’entrevues enregistrées sur bande magnétique.

CONTEXTE

Colombie-Britannique et Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Médecins pratiquant la médecine familiale dans divers milieux et ayant participé à un séminaire sur la TCC.

MÉTHODE

Six mois après un séminaire de 5 heures sur la TCC, les médecins consentants ont été interviewés afin de déterminer leur expérience de l’utilisation de la TCC dans leur pratique. Les entrevues utilisaient un guide semi-structuré; elles étaient enregistrées sur bande magnétique et transcrites textuellement. La méthode comparative constante a été utilisée pour identifier les mots et thèmes clés.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

La plupart des participants déclaraient utiliser des éléments de TCC dans leur pratique. Parmi les facteurs les empêchant d’offrir cette thérapie, ils mentionnaient le manque de temps, les distractions et interruptions inhérentes à la pratique, et l’impression que la TCC ne convenait pas à certains patients. Pour les patients, les obstacles à l’acceptation et à l’utilisation de la TCC étaient leur préférence pour une médication et leur manque de motivation et d’intérêt. Les médecins ont pu contourner certains de ces obstacles en jouant sur la structure de la TCC; cela a permis de réduire la durée des consultations tout en favorisant une meilleure gestion des interruptions. Ils avaient choisi des méthodes de TCC spécifiques à leur pratique et à leurs patients.

CONCLUSION

La plupart des participants considéraient la TCC comme une addition utile à leur pratique et déclaraient avoir réussi à l’implanter. Certains obstacles gênaient toutefois sa mise en œuvre dans les soins primaires. Il faudra tenir compte de ces obstacles si on envisage d’enseigner cette thérapie aux médecins de première ligne pour qu’ils l’offrent à leurs patients.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been proven effective for treating depression and anxiety; success rates for mild-to-moderate cases are similar to those of medication. Family doctors have had difficulty incorporating CBT into practice due to lack of training and time constraints.

This qualitative study examined barriers to introducing CBT into practice and explored how family physicians managed to overcome some barriers.

The main barriers for physicians were lack of time, lack of confidence in the methods, practice distractions or interruptions, and the perception that some patients were poor candidates for CBT. Patient-related barriers were preferences for pharmacotherapy and lack of motivation or interest.

Despite barriers, most of the doctors who attended the CBT training session had incorporated at least some CBT techniques into practice 6 months after the session.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

L’efficacité de la thérapie cognitivo-comportementale (TCC) pour traiter la dépression et l’anxiété est établie; dans les cas légers à modérés, son taux de succès est semblable à celui de la médication. Manque de formation et contraintes de temps sont les facteurs qui empêchent le médecin de famille d’incorporer la TCC à sa pratique.

Cette étude qualitative voulait connaître les obstacles à l’implantation de la TCC dans la pratique et vérifier ce que les médecins de famille font pour contourner ces obstacles.

Pour les médecins, les principaux obstacles étaient le manque de temps et de confiance dans ces méthodes, les distractions et interruptions inhérentes à la pratique, et l’impression que cette technique ne convenait pas à certains patients. Pour les patients, les obstacles étaient leur préférence pour une médication et leur manque d’intérêt ou de motivation.

Malgré ces obstacles, la plupart des médecins qui avaient participé au séminaire sur la TCC 6 mois auparavant avaient incorporé au moins certaines techniques de TCC dans leur pratique.

Family doctors frequently see patients with mental health problems.1 The prevalence of depression among family practice patients ranges from 4.8% to 8.6%.2 Antidepressants are effective for only about 70% of patients. Discontinuation rates among patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are 15% to 25%,3 and side effects are common. Some patients prefer psychotherapy to medication.4 Yet referral resources for counseling are often difficult to access or too expensive for patients to use.5

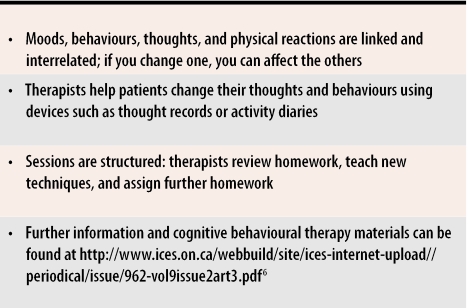

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Table 16) has been extensively researched and found effective for a range of mental health problems, including anxiety and depression.7,8 For mild-to-moderate depression and for preventing recurrences, CBT has been found as effective as antidepressant medication.9,10 A study comparing family therapy, supportive therapy, and CBT showed that CBT resulted in more rapid relief of symptoms and higher remission rates than the other therapies.11 Studies comparing brief cognitive therapy in primary care to usual treatment found that those having brief therapy had higher recovery rates persisting for 12 months.12-15

Table 1.

Aspects of cognitive behavioural therapy

A recent randomized controlled trial of 116 doctors in the United Kingdom, however, found that a short course on CBT had little effect on physicians’ attitudes toward depression or on their patients’ outcomes.15 The authors concluded, “General practitioners may require more extensive training and support if they are to acquire skills in brief cognitive behaviour therapy that will have a positive impact on their patients.”15 Thirty-two doctors dropped out because they lacked the time to take the course.

This study was designed to investigate whether physicians think they can apply CBT principles in their practices, and if so, how, and what the barriers to implementing CBT are.

METHOD

We chose qualitative methods to examine this issue because we wanted to understand the full extent of the problems and successes regarding implementation of CBT rather than merely to examine our own hypotheses on the subject. We interviewed 42 family physicians in Ontario and British Columbia who had participated in a training session on CBT. At the end of each session, all participants were given information about the study and were asked for consent to be contacted and interviewed 6 months later.

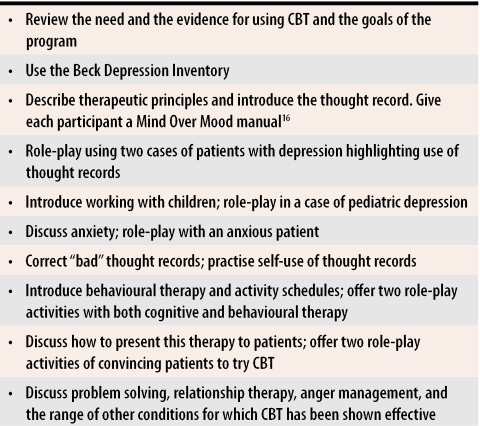

Intervention

Training consisted of 5-hour seminars for groups of eight to 12 family doctors. Each session was led by one of the two authors, who are both family physicians practising comprehensive care. The first session was cotaught by both authors to ensure consistency. We taught skills through role-play, and we allowed time for discussion of problems that could occur in practice. We distributed educational material, such as depression inventories, examples of thought records, a manual, and short lists of suggestions on how to introduce CBT to patients. The sessions were accredited as part of a College of Family Physicians of Canada continuing medical education program (Mainpro-C). The sessions were designed to teach physicians how to use CBT methods within a reasonable amount of time during regular practice. An overview of the course is shown in Table 2.16

Table 2.

Structure of a course on cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT—cognitive behavioural therapy

Data collection

Six months after the session, the investigators contacted consenting participants to arrange telephone interviews. The semistructured interviews included open-ended questions designed to elicit participants’ experiences and difficulties with implementing CBT. The interviews typically lasted 30 to 40 minutes; field notes were taken. After several interviews, we discussed the questionnaire again and sought advice from experts in qualitative methods. We then made minor modifications to the questionnaire.

Analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Because this was an exploratory study, we used a grounded-theory approach.17 After each few interviews, we independently reviewed the data and discussed findings; emerging themes from early interviews were explored and expanded. We used the constant comparative method18 to discover patterns, combinations, and themes. After the 20th interview, we agreed theme saturation had been reached. We decided, however, to continue to interview more participants because they represented different types of practices, and we consciously checked for contradictory observations. No new themes were discovered. The larger sample allowed us to get a sense of the number of physicians who reported using CBT in their practices. In all, we interviewed 42 participants. We then met again to discuss similarities, differences, and potential connections in the data.

The University of British Columbia’s Clinical Screening Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects and the North York General Hospital’s Research Ethics Board granted ethics approval for this project.

FINDINGS

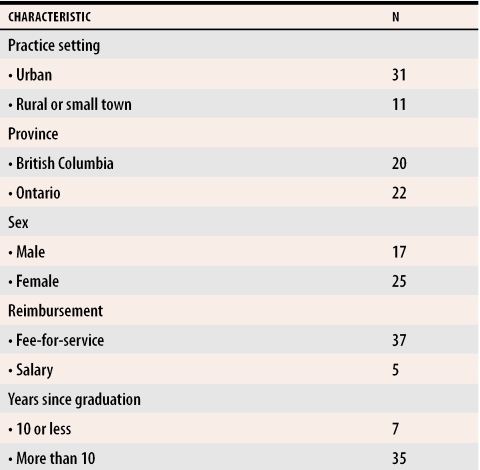

Participants varied by practice location, method of payment, and years in practice (Table 3). Participants not involved in comprehensive family medicine, such as full-time psychotherapists, hospitalists, and physicians practising in walk-in settings only, were excluded from the analysis. No participant reported extensive training in CBT, although many had taken brief courses in various psychotherapeutic modalities.

Table 3. Characteristics of participants.

N = 42.

Barriers to offering CBT

Lack of time.

Of the several barriers to use of CBT in practice, lack of time was the most frequently reported. More than half the fee-for-service doctors, whether they were using CBT or not, complained of this. “I only got two patients because I found it too time-consuming. I see about 45 to 50 patients a day. I try my best to see one or two patients of that nature a week, but I can’t because time is so limited.”

Participants perhaps not ready to implement a change in practice identified time as a barrier. More time is required to apply a new skill, and some doctors noted this. Participants also reported varying levels of use of CBT, depending on the amount of time available in their daily schedules. “Some days I didn’t have them sit down and write it out. We just did a mental exercise due to time constraints, rather than writing it out.”

Lack of confidence.

Only five participants reported lacking confidence in their ability to apply the new skills. Some asked for a follow-up session several months later. “Someone came in to my office about 2 days after the course, and they were just perfect. As a matter of fact, they had heard about it and wanted to do it, and I thought this is an opportunity, but I just didn’t feel …that I would be totally competent.”

Distractions and interruptions.

Several participants mentioned frequent interruptions during sessions as one of the difficulties in implementing CBT. Patients often discuss unrelated problems, which is distracting. Participants viewed this as less of a problem in secondary and tertiary care settings. “If you’re a psychologist, you can ignore schedules, and no one can interrupt you. I’ve seen the nasty notices they put on their doors: ‘Not to be interrupted under any circumstances.’ I get, on average, about two interruptions per visit.”

Participants also talked about the difficulties of “refocusing” in the middle of a busy day. Scheduling a block of time solely for psychotherapy was thought a possible solution. “It’s hard to do when you’ve got a full waiting room. The unpredictable predictably happens. I think the only way to do psychotherapy properly is at the end of a morning, when there is no one else around and your head—the doctor’s head—is clear.”

Patient selection.

Participants reported trying to identify patients who should not be offered CBT. Factors identified as barriers were older age, lower socioeconomic status, lack of education, and not being “psychologically minded.” “The easiest ones are the recently diagnosed and the young, educated persons. But when it comes to middle-aged, 50-year-old persons, they don’t know what I’m talking about. The younger ones, the better-educated ones, are much easier.”

Barriers to patients’ accepting or using CBT

Lack of motivation was frequently identified as a barrier; decreased motivation and concentration could be due to depression. At times, though, physicians thought that apathy was a more pervasive personality trait than temporary lack of motivation due to depression. This problem sometimes interfered with initiation of CBT and with compliance, as patients failed to buy the manual, do homework, or show up for further appointments. Lack of motivation was sometimes expressed as a preference for pharmacotherapy.

These people are very dependent … “sit back and you fix me.” I would go over the chapters I was supposed to go over with them, and show them an example. Some of them would seem very enthusiastic and take the book away. I would make a follow-up appointment. ...[S]ome of the problem was getting them to come to the follow-up appointment for that. I don’t know. Maybe they didn’t need it bad enough. A lot of them, when they came back, would say, “I feel much better” or “I didn’t think I needed to do it,” but a lot of it was “too much effort.”

There was one patient who I thought would be great on it but she said, “No. I want a prescription. I don’t want to work at it. I just want the pill.”

Implementing CBT in practice

Despite the many barriers, 34 of the 42 participants told us they were using CBT methods, such as thought records, thought disputation and reframing, behavioural modification, or a manual, in their practices. The interviews examined self-reported outcomes at 6 months; physicians might or might not have used CBT methods as reported. As part of the Mainpro-C accreditation, physicians sent us photocopies of materials their patients had used (eg, thought records) as evidence that CBT had been used in practice.

Because the methods made intuitive sense, participants reported incorporating CBT principles in other aspects of their lives. If CBT principles are used in daily life, they are more likely to be used in practice. Some physicians reported increased satisfaction, because they felt they were educating patients and giving them ways to help themselves. “It may be something more of a self-help thing they do at home for a while. They feel it helps and life is a little better and they aren’t on medication. This helps a bit, and a little bit can be enough to tip the scales for some people.”

Overcoming barriers

Time.

Some participants were able to incorporate CBT because it helped to structure visits so that they were shorter and seemed more productive. As well, patients were given homework as part of CBT, which might help reduce in-office time. Because some aspects of CBT are not time-consuming, they can be integrated into regular visits.

That was my frustration: I was getting to the time where I wanted to wind it down, “where are we here? We’re still deep in the muddy waters,” they’re going to come out and say, “That was useless,” …. I’ve got to put more structure to what I’m dealing with. Otherwise you might as well book the rest of the afternoon off while they weep and wail about their situation.

You integrate it, that’s what you do. It’s like telling people to get exercise bringing their laundry up from the basement. That’s what family medicine is all about.

Unlike fee-for-service participants, all five salaried physicians reported they had enough time to offer CBT. They recognized that they did not face the same practice pressures as their colleagues.

I don’t think there is any real barrier for me to put this in my practice. I should be doing it more, and I plan to. But my practice is a little bit different from other people’s practices. I do 50% therapy kind of stuff, so I have appointments with adequate time and we do things with people. … I see patients a lot slower than other doctors do. My type of work is not the typical office model.

Confidence.

To overcome lack of confidence with starting a new form of therapy, participants said they reviewed the materials after the course and selected some things to try. As well, they reported waiting for “easier” patients as a confidence-building measure.

Also, I think probably ... you do the course and you still don’t feel real confident in these sorts of things, so you wait for a real good patient to start with and, like a lot of things, if it goes well, try it on a second patient and get a little more confidence in it.

Distractions and interruptions.

Practice interruptions had been mentioned as a barrier. Some participants used the structure of CBT as a way of dealing with interruptions.

The one thing I did notice is that it does work for the interruptions too because you’re trying to do other sorts of psychotherapy. Somebody knocks at the door; you’ve totally lost, often, that moment or train of thought or the patient has certainly; it’s often very hard to get back to that but because it’s very formalized you can say, “Okay, where were we? Oh, we were at this column.” Especially in family practice where we don’t have the luxury of the room at the end of the hall where nobody comes to bother us.

Patient factors.

Some participants were able to help their patients accept CBT by starting small, offering education and patient feedback, and using specific materials.

You had flagged some pages [in the manual]. We’re up north and there aren’t a lot of educated people here, so they don’t want to read an entire book. So I get them to read those pages to start with so they can start doing it. I’m getting them to read those, and I photocopied thought records and I give them a couple of those and tell them to photocopy them on their own. I show them the difference between thought and behaviour and decide with them what we’re going to start with. Maybe we’ll identify a couple of thought things and then we’ll identify some behavioural things. Then we’ll start with understanding the thought records and getting them to do it. Then they’ll come back and show me the record.

DISCUSSION

In a previous trial,15 family physicians involved in brief courses on CBT did not use CBT in their practices and did not show any change in their attitude to depression. Most of our participants reported using elements of CBT in their practices 6 months later, and several participants reported increased satisfaction with their psychotherapeutic approaches. In the previous study, the course was taught by psychologists; in this study, it was taught by family physicians using CBT in their own practices.19 This might have enabled us to suggest practical ways to address participants’ concerns, allowing them to see CBT as feasible. We used a small group, interactive workshop format, which has been shown to be effective in changing practice.20 A recent study using similar educational principles documented an improvement in provision of preventive care in family practices.21

Previous research has identified factors such as time pressures, financial considerations, organizational difficulties, lack of expertise, doctors’ lack of interest, ageism, and patient factors as barriers to implementation of evidence-based recommendations.22-24 In our study, lack of time was most frequently identified as a barrier. The course specifically addressed this issue, as we taught the doctors how to use CBT methods as part of standard office appointments. Several physicians were able to overcome this barrier by using the structure to end the sessions productively and assigning homework to reduce the amount of in-office time. Method of payment might affect use of CBT; all five salaried physicians were using CBT and not complaining about lack of time.

Physicians also mentioned a specific organizational issue, practice distractions, as a barrier. Scheduling time specifically for CBT was proposed as a way to overcome distractions. Physicians in Ontario are allowed to bill for unlimited psychotherapy visits while BC doctors are allowed only four per patient per year. Only Ontario participants talked about wanting to schedule CBT patients at different times from their family practice patients.

Patients’ lack of interest emerged as an important barrier. Patients who prefer psychotherapy tend to do better with CBT.4 In a community survey in the United Kingdom, 91% of respondents indicated that depressed people should be offered psychotherapy, and 16% thought that antidepressants should be offered.25 In this study, participants thought most of their patients would choose pharmacotherapy, sometimes as a “quick fix”; attitudes toward medication in North America might be different from those in the United Kingdom.

Low motivation, a symptom of depression, will affect depressed patients trying to use CBT because they will have trouble doing homework and making follow-up appointments; CBT has been found less effective for severe depression than for mild-to-moderate depression.4 This is also true for any other treatment, including drug treatment and other forms of psychotherapy. Physicians recognized this, and selected patients who were less depressed, or waited for partial remission due to pharmacotherapy. Augmentation therapy with CBT after partial response to antidepressants is an approach supported by evidence.26

Some patients were viewed as being poor candidates for psychotherapy due to apathy or lack of insight. They might not be included in studies of CBT, because they would be less interested in participating. Yet such patients are seen frequently in primary care. Research on developing methods of offering these patients CBT in primary care settings might be worthwhile.

Cognitive behavioural therapy is not “all or nothing”5; participants told us they were able to incorporate some aspects of CBT in their practices. This points to research on patient outcomes with CBT materials in primary care. Research is also needed to determine course content, length, and amount of supervision necessary and adequate for family physicians.

Limitations

Participants in this study were self-selected physicians enrolled in a CBT course. As such, they could have more interest than other physicians in psychological therapies. King et al15 randomly recruited physicians; however, they had a high drop-out rate; less motivated physicians likely excused themselves. Only physicians practising in Ontario and British Columbia were enrolled, so findings might not hold true in other areas. The authors (who were also the instructors) conducted the interviews, which might have biased participants’ responses. Patient outcomes could not be examined in this study.

Conclusion

This short course taught by family physicians and using role-play typically seen in family practice education led to family physicians’ reporting use of CBT skills in practice 6 months later. Physician-related barriers to providing CBT in family practice included lack of time, practice distractions, and the perceived unsuitability of many patients; patient-related factors included lack of motivation, lack of interest in psychology, and preference for pharmacotherapy. Physicians were able to overcome some barriers by applying the structure of CBT to limit office time, by using CBT materials to cope with distractions and fit the therapy into their practices, and by initially selecting “easier” patients.

Acknowledgments

The College of Family Physicians of Canada, through a Janus Project grant, and the Fast Family Foundation at North York General Hospital supported this study. We thank Dr June Carroll and Dr Konia Trouton for reviewing the manuscript and Katayoon Akhavein and Josh Cottrell for their help with transcriptions and data management.

Biographies

Dr Wiebe is a family physician and a Clinical Professor in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Dr Greiver is a family physician affiliated with the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto and the North York General Hospital in Ontario.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Parikh SV, Lin E, Lesage AD. Mental health treatment in Ontario: selected comparisons between the primary care and specialty sectors. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42(9):929–934. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in primary care. Vol 1. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh SV, Lam RW. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders, I. Definitions, prevalence, and health burden. Can J Psychiatry. pp. 13–20. [PubMed]

- 4.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, Gretton V, Miller P, Palmer B, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubord G, Manno M. Cognitive behavioural therapy: incorporating CBT strategies into family practice (educational module). Hamilton, Ont: Foundation for Medical Practice Education; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greiver M. CBT—can be therapeutic. ICES Informed. 2003;9(2):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Treatment choice in psychological therapies and counselling. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. London, Engl: Department of Health Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, Knapp M, McGuire H, Tylee A, et al. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(35):1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta5350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD, Wiemer MJ, Garvey MJ, Grove WM, et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):774–781. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100018004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackburn IM, Moore RG. Controlled acute and follow-up trial of cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy in out-patients with recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:328–334. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(9):877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott C, Tacchi MJ, Jones R, Scott J. Acute and one-year outcome of a randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:131–134. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott J. Cognitive therapy of affective disorders: a review. J Affect Disord. 1996;37(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson P, Bush T, Von Korff M, Katon W, Lin E, Simon GE, et al. Primary care physician use of cognitive behavioral techniques with depressed patients. J Fam Pract. 1995;40(4):352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King M, Davidson O, Taylor F, Haines A, Sharp D, Turner R. Effectiveness of teaching general practitioners skills in brief cognitive behaviour therapy to treat patients with depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324(7343):947–950. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberger D, Padesky C. Mind over mood: change how you feel by changing the way you think. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greiver M. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in a family practice [Practice Tips]. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:701–702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Oxman AD, Wolf F, Davis DA, Herrin J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001(2): CD003030. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Beaulieu MD, Rivard M, Hudon E, Beaudoin C, Saucier D, Remondin M. Comparative trial of a short workshop designed to enhance appropriate use of screening tests by family physicians. CMAJ. 2002;167(11):1241–1246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cranney M, Warren E, Barton S, Gardner K, Walley T. Why do GPs not implement evidence-based guidelines? A descriptive study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(4):359–363. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazareth I, Freemantle N, Duggan C, Mason J, Haines A. Evaluation of a complex intervention for changing professional behaviour: the Evidence Based Out Reach (EBOR) Trial. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):230–238. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khunti K, Hearnshaw H, Baker R, Grimshaw G. Heart failure in primary care: qualitative study of current management and perceived obstacles to evidence-based diagnosis and management by general practitioners. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(6):771–777. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Priest RG, Vize C, Roberts A, Roberts M, Tylee A. Lay people’s attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for Defeat Depression Campaign just before its launch. BMJ. 1996;313(7061):858–859. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7061.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal ZV, Kennedy SH, Cohen NL. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. V. Combining psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(Suppl 1):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]