Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To review the ways attention deficit disorder (ADD) presents in adults in primary care and to suggest treatment approaches.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

PsycINFO, PubMed, and Academic Search Elite databases were searched. Level I evidence supports the effectiveness of stimulants for treating ADD in adults, and mixed evidence (levels I and II) supports the effectiveness of antidepressants.

MAIN MESSAGE

Attention deficit disorder is a prevalent but often unrecognized disorder in adults. The diagnosis, which must include onset of symptoms before age 7, is often missed. This could be because family physicians are not always familiar with the presentation in adults, because it frequently presents with comorbid problems, or because specific questions are not asked to elicit the diagnosis. Diagnosis is based on clinical assessment often assisted by self-rating scales. Management includes support and education, helping patients develop additional structure in their lives and make necessary behavioural changes, enhancing self-esteem, supporting and educating families, and prescribing medication. Medication choices include stimulants and antidepressants; medication can benefit up to 60% of people with ADD.

CONCLUSION

It is crucial for primary care physicians to identify ADD in adults and to initiate treatment or referral. Several simple interventions can be employed.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Faire le point sur le mode de présentation du trouble déficitaire de l’attention (TDA) chez l’adulte en médecine de première ligne et suggérer des stratégies de traitement.

SOURCE DE L’INFORMATION

Une recherche a été effectuée dans les bases de données PsycINFO, PubMed et Academic Search Elite. Il existe des preuves de niveau I à l’effet que les stimulants constituent un traitement efficace du TDA et des preuves mixtes (de niveaux I et II) indiquant que les antidépresseurs sont efficaces.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Même si le trouble déficitaire de l’attention est relativement fréquent chez l’adulte, il passe souvent inaperçu. Son diagnostic, qui doit inclure un début avant l’âge de 7 ans, est souvent manqué. La raison pourrait être que les médecins de famille ne sont pas toujours familiers avec son mode de présentation chez l’adulte, que sa présentation est souvent compliquée de comorbidité ou qu’on omet de poser les questions précises qui permettent de l’identifier. Le diagnostic repose sur l’évaluation clinique, souvent complétée par des échelles d’auto-évaluation. Le traitement comprend du support et de l’éducation, des mesures pour permettre au patient de développer de nouvelles stratégies dans sa vie, de faire les changements comportementaux qui s’imposent et d’améliorer l’estime de soi, un support et de l’éducation pour la famille, et la prescription d’un médicament, soit un stimulant ou un antidépresseur. Jusqu’à 60% des personnes souffrant de TDA peuvent bénéficier de la médication.

CONCLUSION

Il est très important que le médecin de première ligne puisse identifier le TDA chez l’adulte et instaurer un traitement, sinon demander une consultation. Plusieurs interventions simples sont disponibles.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Attention deficit disorder (ADD) is more common in adults than is usually recognized in family practice. About 3% to 6% of the adult population is affected. The multitude of psychosocial problems that stem from ADD make it important for family doctors to recognize and treat it.

About half of ADD patients have comorbid conditions, such as mood disorders (depression, bipolar affective disorders, dysthymia), anxiety, addictions, or personality disorders.

Diagnosis can be made by asking specific questions, (eg, difficulties concentrating, completing tasks), using self-rating scales, or applying criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) or from other sources.

Management approaches work best if they integrate education, building self-esteem, behaviour modification, providing structure, family support, and medication.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Le trouble déficitaire de l’attention (TDA) est plus fréquent chez l’adulte qu’on ne le reconnaît généralement en médecine familiale. Environ 3 à 6% des adultes en sont affectés. Vu les nombreux problèmes psychosociaux que ce trouble entraîne, il est important que le médecin de famille sache le reconnaître et le traiter.

Environ la moitié des cas de TDA s’accompagnent de comorbidité, telles des troubles de l’humeur (dépression, troubles affectifs bipolaires, dysthymie), de l’anxiété, de la toxicomanie ou des troubles de la personnalité.

Le diagnostic peut être établi par des questions spécifiques (p.ex. sur la difficulté à se concentrer ou à compléter les tâches), à l’aide d’échelles d’auto-évaluation ou à partir des critères provenant, entre autres sources, du Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, quatrième édition (DSM-IV).

Les stratégies de traitement sont plus efficaces si elles intègrent l’éducation, l’amélioration de l’estime de soi, une modification du comportement et l’apport de structure, d’un soutien familial et d’une médication.

Attention deficit disorder (ADD) in adults is a common but unheralded problem.1 Recent studies have estimated its prevalence in children at 6% to 9%,2 and have suggested that 40% to 70% of these children will continue to experience symptoms as adults.3-7 This suggests that between 3% and 6% of the adult population have symptoms of ADD that interfere to some degree with their day-to-day vocational, social, and family functioning. This would make ADD one of the most prevalent of all psychiatric disorders, even though prevalence rates gradually decrease with age.8 Detecting ADD is particularly important because people with the condition have poor psychosocial outcomes including higher rates of school failure, incarceration, work instability, and substance abuse,3,9 and higher levels of comorbid psychiatric disorders.4-6

Adult ADD is of particular relevance to family physicians because these people usually present in primary care, often with seemingly unrelated or coexisting problems, which is why the diagnosis is frequently missed. Family physicians’ role is to suspect the possibility of ADD, confirm the diagnosis, and initiate a comprehensive treatment plan that includes referral to mental health services if required. Family physicians can also manage and support those with ADD not being treated in, or having been discharged from, mental health services and can ensure that care remains well coordinated.

Quality of evidence

Databases searched were PsycINFO, PubMed, and Academic Search Elite. Although there are fewer studies of adults than of children, there is level I evidence of the effectiveness of both short-acting and slow-release stimulants for patients with ADD. Some level I evidence supports use of antidepressants and other treatments for adults; most evidence is level II.

Etiologic theories

Neurobiologic factors appear to play a role in onset of ADD. Studies of twins and adoptions offer strong evidence of a genetic link, and 20% of parents of children with ADD have the problem themselves.10 Two dopamine receptor genes and the DAT gene11,12 have been identified as possibly having a role.

People with ADD might have problems in the prefrontal cortex that would affect dopamine and noradrenaline levels12 and structural changes in the striatum and the cortex.13 Barkley14 and Castellanos15 have both postulated a possible mechanism for ADD as a loss of some of the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex, such as emotional control and the ability to integrate various demands and emotions. This would diminish capacity for goal-directed behaviour and self-regulation of mood and increase the likelihood of impulsive behaviour.

Comorbidity

Half of those with ADD have comorbid psychiatric disorders3,4,16: 19% to 37% have mood disorders (depression, bipolar affective disorders, and dysthymia), 25% to 50% have anxiety disorders, 32% to 53% have addiction problems, and 10% to 28% have personality disorders.3,4,13,17,18 This comorbidity is why the diagnosis is often missed, even though the comorbid problems are addressed and treated.

Assessment

Consider ADD when patients describe specific problems or behaviours.

Clues that suggest presence of ADD include instability in work and relationships; self-reports of disorganization or problems completing tasks; history of school problems of various kinds; and in some instances, drug and alcohol use. Recurring (and consistent) problems in various areas of patients’ lives, rather than a single problem in just one area, suggest the possibility of ADD. Patients might also describe symptoms of restlessness or mood swings or problems focusing. These problems are sometimes overlooked or mistaken for symptoms of other disorders, such as anxiety or depression.

Ask specific questions.

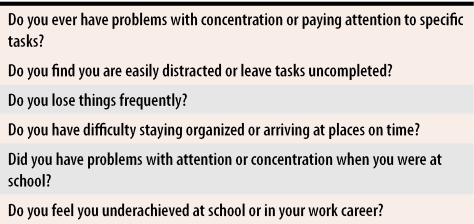

Table 1 lists questions that can easily be asked during a clinical interview.

Table 1.

Questions for assessment

Use self-rating scales.

Self-rating scales19-21 can help detect specific behaviours, but in the end, diagnosis will be based on a clinical interview and presence of symptoms that meet the diagnostic criteria outlined below. One easy-to-use scale developed for primary care providers by the World Health Organization is the Adult ADD Self-Report Scale, available to download at http://www.med.nyu.edu/psych/assets/adhdscreener.pdf.

Assess for other psychiatric disorders.

Physicians should assess symptoms suggesting anxiety, depression, mood swings, and addiction problems, all of which can mask or mimic symptoms of ADD.

Diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic test, but there are at least three commonly used frameworks for diagnosing ADD in adults. Common to all cases is that symptoms started before age 7. If there were no symptoms before age 7, the diagnosis cannot be made.

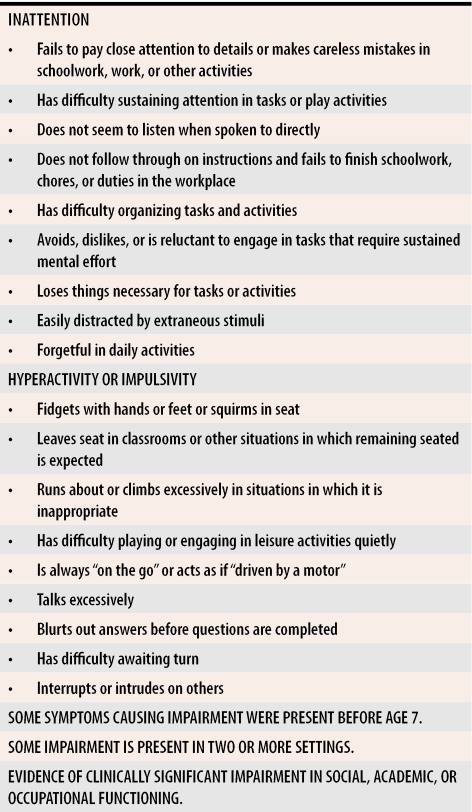

One classification can be found in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV),7 although the criteria in the DSM-IV were developed primarily for children rather than adults. The DSM-IV groups ADD symptoms into inattention and impulsivity or hyperactivity, or a combination of the two (Table 2). Attention deficit with hyperactivity is referred to as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but in this article, the term ADD covers both ADD and ADHD. To make the diagnosis there needs to be:

Table 2. DSM-IV criteria for attention deficit disorder (ADD).

Six or more symptoms out of nine of inattention or six or more symptoms out of nine of hyperactivity or impulsivity present for at least 6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with development level suggest ADD.

a history of onset before age 7,

at least six symptoms from a list of nine for attention problems or six from a list of nine for impulsivity or hyperactivity, and

evidence that symptoms have been present for more than 6 months, are pervasive and maladaptive, and affect at least two domains of the patient’s life.

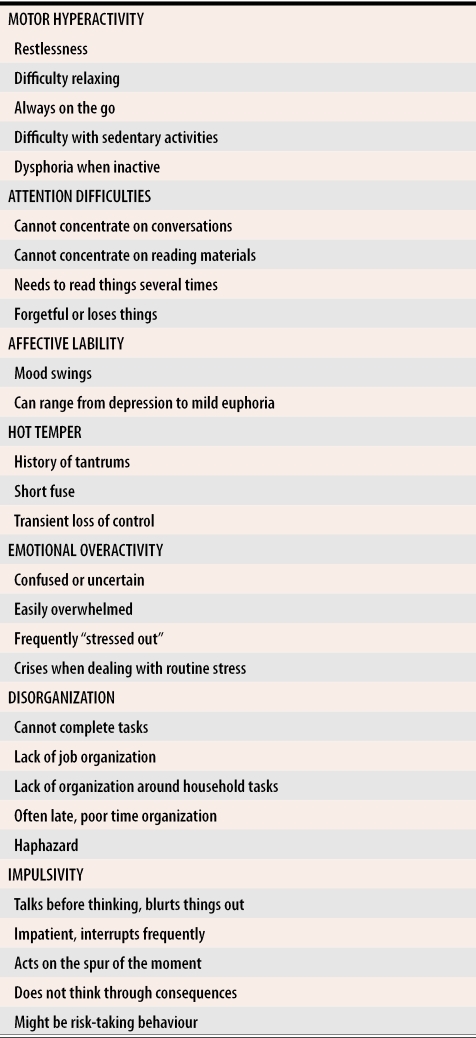

Wender has broadened these criteria.3 He identified seven subcategories: inattention, motor hyperactivity, impulsivity, disorganization, hot temper, emotional overactivity, and mood swings. To make the diagnosis, behaviours must be present in the inattention and hyperactivity subcategories and in at least two categories of the other five(Table 33).

Table 3.

Wender’s criteria for attention deficit disorder in adults

Adapted from Wender.3

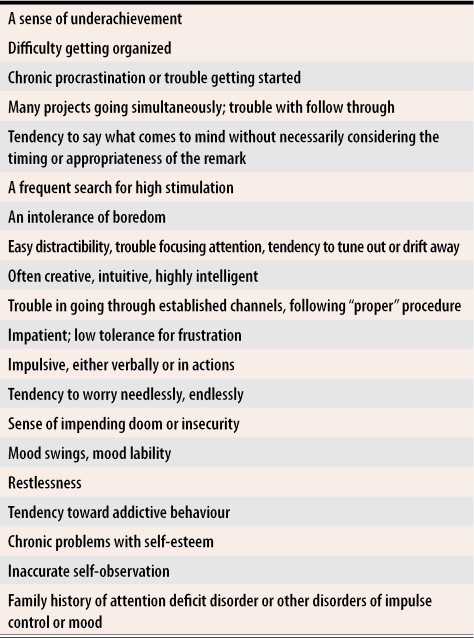

Hallowell and Ratey22 have further expanded the criteria by identifying a list of 20 behaviours; 12 need to be present to make the diagnosis (Table 422). These criteria are easy to use in primary care.

Table 4. Hallowell and Ratey’s criteria for diagnosing attention deficit disorder.

12 out of 20 criteria need to be present.

Adapted from Hallowell and Ratey.22

Diagnosis of ADD can be confirmed by obtaining corroborative history from partners, friends, or other family members who might highlight behaviour patients have overlooked or downplayed. It is worth asking for school records, as they can often reveal attention problems, and adults do not always report childhood symptoms accurately.23 Eliciting a full family history is important. This should also cover related problems, such as tics, criminal activities, and drug or alcohol use. The extent to which these symptoms interfere with daily activities is also important, as it will determine whether treatment is required.

Management

Although there is little evidence from studies of adults, studies of children (level I evidence) suggest the best outcomes derive from integrated treatment approaches24 that include educating patients about ADD; maintaining self-esteem; suggesting behavioural changes, including providing more structure; family interventions and support; and medication. Most of these approaches can be implemented successfully in primary care.

Education.

Helping patients recognize that ADD is a problem they can do something about begins to give them back a sense of control and paves the way to using specific structural and behavioural measures. Education can be facilitated by reading materials and use of websites such as Children and Adults with Attention Deficit Disorder (CHADD) (http://www.chaddcanada.org).

Self-esteem.

A common consequence of ADD is low self-esteem or self-confidence that results from failure at school, difficulties in the workplace, negative comments of others, difficulties in social adjustment because of impulsive behaviour, or failure in relationships. Techniques for maintaining and enhancing patients’ self-esteem include acknowledging accomplishments and changes made, challenging negative comments or thoughts people make about themselves and assisting them to replace these negative thoughts with more positive ones, helping patients avoid situations where they could be setting themselves up to fail, and setting attainable goals.

Behavioural changes and providing structure.

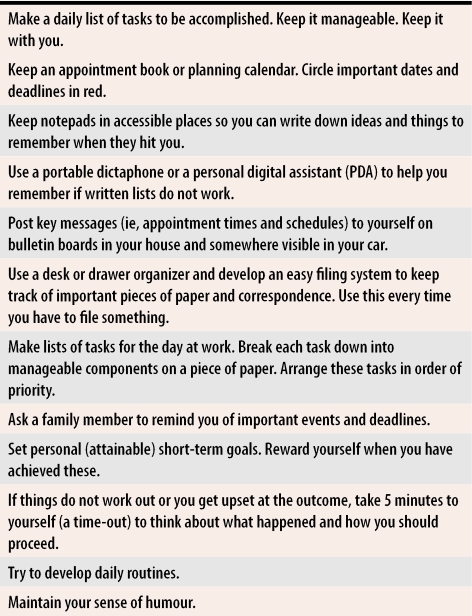

Ways to help patients put more structure or organization in their days, such as developing daily routines and using lists and reminders, are summarized in Table 5. Setting goals helps; goals should be clear, short-term, and attainable, and should give a sense of accomplishment when reached.

Table 5.

Strategies for managing symptoms of attention deficit disorder

People with ADD can also be helped to recognize particular triggers for impulsive behaviour. They can then learn various responses to these triggers, including waiting before acting, evaluating a situation, and working out possible courses of action. Wilens and McDermott25 have summarized these responses using the acronym SPEAR (Stop, Pull-back, Evaluate, Act, Reassess).

Family interventions.

Involving other family members can be useful.22,26 They can provide corroborative information on their relatives’ behaviour and symptoms and receive information on what ADD is and how it can be treated. Family members can also assist with strategies, such as preparing reminder lists, that will reduce patients’ symptoms.

Medication.

For many people, especially those with milder, less disruptive symptoms, nonpharmacologic approaches suffice. If symptoms are more severe or have a greater or destructive effect on patients’ lives, medication should be considered.24

Management of ADD relies on two groups of drugs: stimulants, such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) or dexamphetamine (Dexedrine), and antidepressants, such as tricyclics, buproprion, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Stimulants:

The few double-blind trials of stimulants have found variable response rates (25% to 78%, mean 52%) with no evidence that their use led to tolerance or abuse.27,28 Recent meta-analyses of placebo-controlled crossover trials found methylphenidate to be efficacious for treating ADD in adults29; average response rates were 58% for methylphenidate, 57% for dexamphetamine, and 10% for placebo.27 Symptom reduction might be related to dose, with higher doses (if tolerated) bringing better responses. Optimal doses are achieved when further increases in dose no longer bring clinical improvement.24

Long-acting drugs:

Methylphenidate and dexamphetamine both come in short-acting forms (usually 3 to 4 hours’ duration) and a slow-release form that lasts about 7 to 8 hours. Newer slow-release medications are Concerta,30 a combination of immediate-release and slow-release methylphenidate, and Adderall,31 a combination of amphetamine salts. Both of these last for 10 to 12 hours. Atomoxitene (Stratera),32 an SNRI, is likely to be available soon in Canada.

Slow-release pills have a slower onset of action but a smoother course and fewer rebound symptoms as the dose wears off. Taking a medication just once a day can improve compliance. Slow-release and short-acting drugs can be combined: short-acting agents can “top up” the effects of long-acting agents during the day. Side effects can include decreased appetite, disrupted sleep, restlessness or agitation, and rebound symptoms as drugs wear off.

Some adults choose to take their stimulants only when required, such as when they have a particular task requiring concentration or a project to complete. Others feel more comfortable if they have the protection medication offers around the clock.

Stimulants should be started with a small single dose (5 to 10 mg of methylphenidate or 5 mg of dexamphetamine) usually in the morning. Response should be monitored.24 The dose can then be titrated up in small (5-mg) increments every 4 to 7 days according to response, initially on a once-daily basis. Once response and benefits are ascertained, a second dose can be initiated, usually after lunch. A smaller dose can be tried in the early evening if sleep has not been a problem. If an increase in dose fails to further alleviate symptoms, the dose should be reduced to the previous effective level. An average daily dose is 20 to 80 mg of methylphenidate and 10 to 40 mg of dexamphetamine.24

Antidepressants:

All evidence supporting use of antidepressants is level II. The strongest evidence is for buproprion33,34 and tricyclics (desipramine or noradrenaline).35 Evidence is weaker for venlafaxine,36 especially if there is an accompanying mood disorder. There is little evidence of benefit from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.37 Antidepressants should be initiated and increased as they would be for treating depression.

Choice of medication:

Individual preference will always be an important factor, and many people have strong feelings about taking stimulants. In general, if the problem is predominantly with cognitive symptoms and attention, the first choice should be a stimulant. If mood symptoms are severe, an antidepressant should be considered unless patients think treating problems with attention and disorganization is their main priority.

Drugs can also be used in combination, but it is wise to start one first and assess response and residual symptoms before adding a second. One advantage of stimulants is that they act fairly quickly, and a trial can be completed within a couple of weeks.

Symptoms of ADD might improve over the years, and this could reduce the need for medication.8 Development of new skills and increased self-confidence can also change medication requirements. It is worth reviewing progress after a 6-month trial of medication, and then at least annually, particularly for adults who have continued taking the same dose since they were teenagers.

Conclusion

Attention deficit disorder is a prevalent condition that affects as many as 3% to 6% of all Canadian adults. Most cases are seen in primary care; a few cases are referred to mental health services. The condition is associated with a high degree of psychiatric comorbidity, particularly depression. Other social problems include work difficulties and low self-confidence. While comorbidity might mask its presence, clues to behaviour suggesting ADD can be elicited with routine questioning; a fuller interview can confirm the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, an integrated treatment plan, including education, behaviour management, family support, and medication, can be implemented. Family physicians have a key role in detecting ADD, initiating treatment, involving other family members, and monitoring their patients’ progress.

Biography

Dr Kates, a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences with a cross-appointment in the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, is Director of the Hamilton Health Services Organization Mental Health and Nutrition Program.

References

- 1.Lamberg L. ADHD often undiagnosed in adults: appropriate treatment may benefit work, family, social life. JAMA. 2003;290:1565–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1158–1170. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wender PH. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troller J. Attention deficit disorder in adults: conceptual and clinical issues. Med J Aust. 1999;171(8):421–425. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biederman J. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a life-span perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):4–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy-Byrne P, Scheele L, Brinkley J, Ward N, Wiatrak C, Russo J, et al. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: assessment guidelines based on clinical presentation in a specialty clinic. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38(3):133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992. pp. 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkley R, Murphy K. ADHD: a clinical workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adler L, Cohen J. Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psych Clin North Am. 2004;27(2):187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wender PH. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss M, Trokenberg-Hechtman L, Weiss G. ADHD in adulthood: a guide to current theory, diagnosis, and treatment. Baltimore, Md: John Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Faraone S. Overview and neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 12):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss M, Murray C. Assessment and management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. CMAJ. 2003;168(6):715–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkley R. ADHD and the nature of self-control. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellanos F. Psychobiology of ADHD. In: Quay H, Flynn A, editors. Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders. New York, NY: Plenum; 2000. pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arcia E, Conners CK. Gender differences in ADHD? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19(2):77–83. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199804000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Norman D, Lapey KA, et al. Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1792–1798. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornig M. Addressing comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):885–890. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown TE. Brown attention-deficit disorder scales manual. San Antonio, Tex: Harcourt Brace and Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow EP. Conners adult ADHD rating scales. Technical manual. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallowell EM, Ratey J. Driven to distraction: recognizing and coping with attention deficit disorder from childhood through adulthood. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Klein DF, Besslere A, Shrout P. Accuracy of adult recall of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1882–1888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, Bernet W, Arnold V, Beitchman J, et al. Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(Suppl 2):26–49. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilens T, McDermott S. Cognitive therapy for adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Brown TE, editor. Attention-deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents, and adults. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. pp. 569–607. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bemporad JR. Aspects of psychotherapy with adults with attention deficit disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;931:302–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy K. Empowering the adult with ADD. In: Nadeau K, editor. A comprehensive guide to attention deficit disorder in adults. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1995. pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J. A review of the pharmacotherapy of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2002;5(4):189–202. doi: 10.1177/108705470100500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faraone SV, Spencer T, Aleardi M, Pagano C, Biederman J. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of methylphenidate for treating adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(1):24–29. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000108984.11879.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson J, Greenhill LL, Pelham W, Wolraich ML, Wilens T, Palumbo D, et al. Initiating Concerta (OROS methylphenidate HCl) qd in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Res. 2000;3:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faraone SV, Biederman J. Efficacy of Adderall for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2002;6(2):69–75. doi: 10.1177/108705470200600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, Reimherr FW, West FA, Allen AJ, et al. Atomoxitene in adults with ADHD: two randomised, placebo-controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(2):112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Girard K, Doyle R, Prince J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):282–288. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuperman S, Perry PJ, Gaffney GR, Lund BC, Bever-Stille KA, Arndt S, et al. Buproprion SR vs. methylphenidate vs. placebo for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13(3):129–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1012239823148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Warburton R, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(9):1147–1153. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornig-Rohan M, Amsterdam J. Venlafaxine versus stimulant therapy in patients with dual diagnosis ADD and depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):585–589. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wender PH, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J. Adults with ADHD. An overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;931:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]