Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine factors associated with re-utilization of health services and to estimate and compare costs of treatment for minor acute illnesses in family physicians’ offices (FPOs), walk-in clinics (WICs), and emergency departments (EDs).

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study using questionnaires, telephone follow up, medical chart data, and costs according to Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) schedules.

SETTING

16 FPOs, 12 WICs, and 13 EDs in three Ontario cities.

PARTICIPANTS

Consecutive patients with one of eight predefined minor acute illnesses found in all three settings (upper respiratory infection, pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, acute otitis media, serous otitis media, low back pain, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infection).

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

“Early” (<3 days) versus “later” (3 days to 2 weeks) re-utilization of health services after initial encounter and direct cost to OHIP.

RESULTS

The overall rate of re-utilization of health services for the same episode of illness was 11.3% for early and 20.6% for later re-utilization. Factors associated with early re-utilization were initial evaluation in ED setting (odds ratio [OR]=6.5, confidence interval [CI]=2.2-19.2) and, regardless of setting, less satisfaction with patient-centred care (OR=1.7 for each one-point decrease on a four-point scale; CI=1.1-2.7). Factors associated with later re-utilization were ED setting (OR=4.9; CI=2.4-9.9) and diagnosis of urinary tract infection (OR=2.4; CI=1.1-5.2). Factors tested and found not signifcantly associated with rate of re-utilization were patients’ age, sex, responses to a variety of questions assessing psychosocial factors (stress, social support, independence), and opinions on health care. Cost of care was similar for FPOs and WICs and higher for EDs for all diagnoses. The initial visit was the largest component of cost in all settings, and this component (as well as total cost) was consistently higher in EDs.

CONCLUSION

Both re-utilization rates and costs are higher for those seeking care in EDs for minor acute illness. Patient-centred care, an important feature of health care encounters regardless of setting, can reduce re-utilization rates.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer les facteurs associés à une réutilisation des services, de santé et évaluer et comparer les coûts selon qu’une maladie aiguë mineure est traitée au cabinet d’un médecin de famille (CMF), à une clinique sans rendez-vous (CSR) ou dans un service d’urgence (SU).

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Étude de cohorte prospective utilisant des questionnaires, un suivi téléphonique, les dossiers médicaux et les coûts d’après les tarifs de l’Assurance Santé de l’Ontario (OHIP).

CONTEXTE

Seize CMF, 12 CSR et 13 SU dans trois villes de l’Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Les patients consultant consécutivement ces trois milieux pour l’une des huit maladies aiguës mineures suivantes: infection des voies respiratoires supérieures, pharyngite, bronchite aiguë, otite moyenne aiguë, otite moyenne séreuse, douleur lombaire, gastro-entérite ou infection urinaire.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Réutilisation des services de santé précocement (< 3 jours) versus plus tardivement (3 jours à 2 semaines) suivant la consultation initiale et coûts direct pour l’OHIP.

RÉSULTATS

Le taux global de réutilisation des services de santé pour le même épisode de maladie était de 11,3% pour les réutilisations précoces et de 20,6% pour les réutilisations tardives. Les facteurs associés à une réutilisation précoce étaient une première évaluation dans un SU (rapport des cotes [RC] = 6,5 ; intervalle de confiance [IC] = 2,2-19,2) et, sans égard au contexte, une moindre satisfaction pour l’aspect « soins centrés sur le patient » (RC = 1,7 pour chaque diminution d’un point sur une échelle en quatre points ; IC = 1,1-2,7). Les facteurs associés à une réutilisation plus tardive étaient un contexte de SU (RC = 4,9 ; IC = 2,4-9,9) et un diagnostic d’infection urinaire (RC = 2,4; IC = 1,1-5,2). Les facteurs qui n’ont pas montré de relation significative avec le taux de réutilisation étaient l’âge et le sexe des patients, leurs réponses à diverses questions d’évaluation des facteurs psychosociaux (stress, soutien social, indépendance) et leur opinion sur les soins de santé. Les coûts des soins étaient semblables pour les CMF et les CSR, mais plus élevés pour les SU, sans égard au diagnostic. La visite initiale représentait la plus grande composante des coûts, quel que soit le contexte, et cette composante (à l’instar du coût total) était régulièrement plus élevée dans les SU.

CONCLUSION

Les taux de réutilisation de même que les coûts sont plus élevés lorsqu’on consulte un SU pour une maladie aiguë peu sévère. Des soins centrés sur le patient, une caractéristique importante de toute consultation médicale peu importe le contexte, peuvent réduire les taux de réutilisation.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This analysis of the Ontario Walk-In Clinic Study data showed that initial visits for minor illnesses to emergency departments (EDs) were associated with higher re-utilization rates than visits to family physicians’ offices (FPOs) or walk-in clinics (WICs).

Costs of treating minor illnesses were substantially higher in EDs.

Contrary to common perceptions, re-utilization rates and costs were not significantly different between FPOs and WICs.

In any setting, less satisfaction with patient-centred care was associated with higher rates of re-utilization.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Cette analyse des données de l’Ontario Walk-In Clinic Study montre que les visites initiales à un service d’urgence (SU) pour une maladie mineure entraînent un plus fort taux de réutilisation par rapport aux visites à des cabinets de médecins de famille (CMF) ou à des cliniques sans rendez-vous (CSR).

Pour les maladies peu sévères, le coût du traitement était significativement plus élevé dans les SU.

Contrairement à une opinion courante, il n’y avait par de différence significative entre les CMF et les CSR pour ce qui est des taux de réutilisation et des coûts.

Indépendamment du contexte, un plus faible taux de satisfaction concernant l’aspect « soins centrés sur le patient » était associé avec un plus fort taux de réutilisation

Acute, nonurgent illness accounts for up to 30% of ambulatory health care visits.1-4 Such visits typically occur in three settings: family physician’s offices (FPOs), walk-in or urgent care clinics (WICs), and emergency departments (EDs).

The growing popularity of WICs in Ontario is a mixed blessing. Because WICs often deal with minor acute problems, FPOs are left with more complex and time-consuming problems.5 As well, both family physicians6 and patients7 value continuity of care, which is not usually a feature of WICs. On the other hand, time has become an important commodity and patients value convenience in services.5,8 Moreover, patients have increased confidence in their own knowledge and ability to make their own health care decisions.5,8

Some physicians have expressed concern that use of WICs will result in duplication of service.9,10 Such duplication would occur if a patient went to a WIC and subsequently visited his or her own FPO for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment. Opinions on whether duplication actually occurs vary, and an electronic search using PubMed revealed only one study of this question. Bell and Szafran10 surveyed patients in their waiting room on past use of WIC services. Their study, although possibly biased by its retrospective method, identified re-utilization as a potential concern. This is clearly an important question that needs further study.

In recent years, concern has also increased about the relative costs of care in FPOs, WICs, and EDs, particularly in the United States.3,11,12 In Canada, however, little research has investigated relative costs for acute, nonurgent care in these settings. Overall per capita hospital expenditures and ED expenditures are lower under Canada’s universal insurance system than expenditures in the United States, despite higher rates of hospital admission and outpatient visits in Canada.13 Thus, it might be inappropriate to base Canadian health care policy on US cost estimates. It is interesting to compare the costs among settings because, although EDs have high fixed costs,12,14 greater use does not necessarily lead to higher marginal costs. No studies to date have examined the costs of care for acute minor illness to provincial ministries of health in Canada.

This paper is based on case studies of Ontario patients receiving care in FPOs, WICs, and EDs for minor acute illnesses. The objectives were first to examine factors associated with, and reasons for, re-utilization of health care resources after an initial health care encounter and second to estimate and compare per-patient direct costs to the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC) for episodic care for six common, acute minor illnesses in the three settings (FPO, WIC, ED).

METHOD

This study was one component in a series of multicentre projects entitled “The Role and Impact of Walk-in Clinics in Ontario’s Health Care System.”15 Ethics committee approvals were obtained from the three participating universities (University of Western Ontario, University of Toronto, and McMaster University).

Sampling of sites has been described in detail elsewhere.16 The Ontario communities of Hamilton-Burlington, Toronto, and London were chosen because they have a relatively high concentration of WICS, have a distribution of all three setting types, and were readily accessible to the researchers. Sites approached to participate included 35 FPOs (32 chosen by random selection and three by targeted recruitment to achieve geographic balance), 20 WICs (chosen by random selection from 11 geographic regions in the three cities), and 13 EDs (random selection in Toronto, complete census in London and Hamilton-Burlington). Sixteen FPOs, 12 WICs, and 13 EDs participated.

Settings were defined as follows: a practice where more than 50% of the patients were cared for on a regular basis was considered an FPO; a practice where fewer than 50% of the patients were regular patients was considered a WIC; and hospital-based, 24-hour medical emergency facilities were considered EDs. Patients in WICs were included only if WICs were not their regular source of primary care. Patients in FPOs were included only if they were regular patients.

Subjects were recruited when they presented at FPOs, WICs, and EDs for initial care during an episode of illness. To reduce variation in patient mix and to restrict our sample to minor acute illness, only patients with eight tracer conditions were included: upper respiratory infection (URI), pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, acute otitis media, serous otitis media, low back pain, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infection (UTI). These conditions selected by an expert panel were common to all three settings. These conditions were later collapsed into six categories combining pharyngitis with URI and acute with serous otitis media for analyses pertaining to re-utilization. Subjects were approached while they were waiting to see physicians. They were potentially eligible if the complaint that brought them there that day matched one or more of the symptoms listed on a card carried by the recruiter. Eligibility was verified by chart review after the visit.

Before seeing a physician, the patient or the initiator of the visit (ie, caregiver) completed a 10-minute interviewer-administered questionnaire on factors thought to influence re-utilization rate or cost. Interviewers were trained to enhance consistency of technique. After the encounter, subjects completed a 5-minute self-administered questionnaire regarding the encounter and asking whether patients had been told they should be seen again.

Sample size was estimated in order to address the objectives of a companion study regarding patient satisfaction and quality of care and has been reported.15 An estimated 150 subjects per setting (total 450 subjects) were required.

Factors associated with re-utilization

Re-utilization was defined as subsequent use of health care resources, in any setting, for the same episode of illness. Follow up was in two periods: within the first 3 days (“early”) and from 3 days to 2 weeks after the initial encounter (“later”). Subjects were contacted by telephone 3 days after the initial encounter. If they could not be reached, the interviewer tried for 2 more days. The telephone survey (< 5 minutes) ascertained the number of additional times patients had visited a physician for the same episode of illness as well as the location(s) and reasons for the visits.

If, at the 3-day interview, subjects had completely recovered from the initial complaint and had no intention of making further visits for the same problem, they were not contacted again because, by definition, the initial episode of illness had ended. All other subjects were contacted again approximately 2 weeks after the initial encounter and were asked the same questions about re-utilization. For both the 3- and 14-day follow-up calls, a minimum of four calls was attempted before declaring the case lost to follow up.

Factors investigated for possible association with re-utilization included covariates measured before the encounter (setting, age, sex, education, income, marital status, self-reported health status, whether patients had regular family physicians, accessibility of health care settings contacted, and perceptions of the severity and urgency of the illness) and after the encounter (three measures of patient satisfaction: the patient-centred focus of the encounter, the physician’s attitude, and the delay in the waiting room15,16). Multivariable analyses of factors associated with re-utilization used logistic regression with backward stepwise elimination with P-to-remove set at 0.15. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated.

Direct costs of health care delivery

Direct costs to the MOHLTC, the single payer for Ontario’s universal health care system, for the presenting complaint were assessed. Initial visit costs, follow-up costs, and laboratory costs for the initial visit were obtained from several sources. Costs were assigned to the setting of the initial health care encounter. Data regarding the initial visit, laboratory tests, and imaging were abstracted from medical charts by 12 experienced abstrators. Intraobserver and interobserver reliability were both assessed and had a reliability coefficient of 0.89. Details have been published elsewhere.15

Physician charges to the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) for initial and follow-up visits in each setting were obtained from the OHIP Schedule of Benefits. In order to identify physician charges for each condition, a convenience sample of eight physicians (four from FPOs, two from WICs, and two from EDs) was surveyed regarding the usual OHIP billing code for both initial and follow-up visits for the eight diagnoses studied.

Private laboratory testing charges were obtained from the OHIP Schedule of Laboratory Fees. Because laboratory testing charges at EDs are paid by the MOHLTC as part of a hospital’s global budget, representative charges for individual tests were obtained from the case-costing department at London Health Sciences Centre’s University campus.

Costs of imaging, for the 17 patients who had imaging, were also estimated using the OHIP Schedule of Benefits. For URI and acute bronchitis diagnoses, if the chart indicated that x-ray films had been taken but had not specified details, then we assumed that these were chest films (two views). If the chart indicated unspecified x-ray films for gastroenteritis and UTI, these were assumed to be abdominal films (single view). An estimate of ED overhead per patient visit was obtained from the case-costing department at London Health Sciences Centre’s University campus. Overhead was estimated using the Meditech case-costing system for nursing emergency acuity Type I patients. Both fixed and variable costs were included.

Costing data obtained were combined with utilization data to estimate costs for individual patients within each diagnostic condition. Total cost was determined by adding the initial visit cost, follow-up visit cost, and laboratory cost. Linear regression analysis was used to estimate mean cost differences between settings, with age stratification as appropriate. To evaluate the effect of assumptions we made in constructing cost estimates, nine one-way sensitivity analyses were conducted that varied cost components.

RESULTS

Factors associated with re-utilization

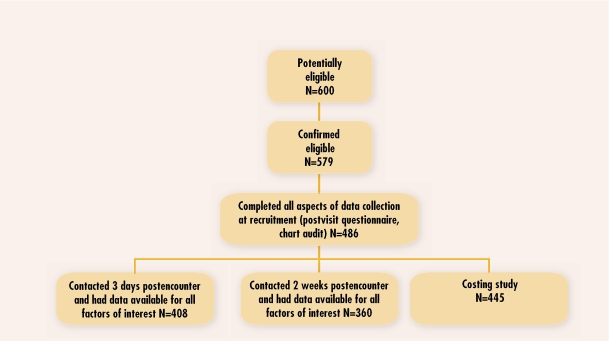

Of 486 subjects who completed both the previsit and postvisit questionnaires, complete data on all variables of interest plus early (3 days) or later (2 weeks) postencounter data were available for 408 and 360 subjects, respectively (Figure 1). The sample has been described elsewhere.15

Figure 1.

Recruitment and retention of subjects used in analyses

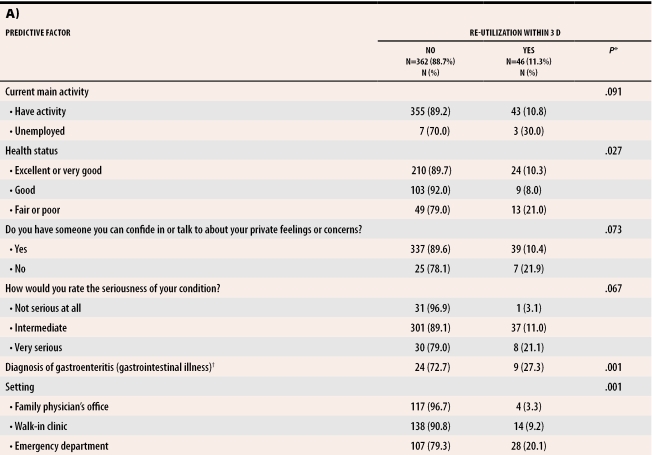

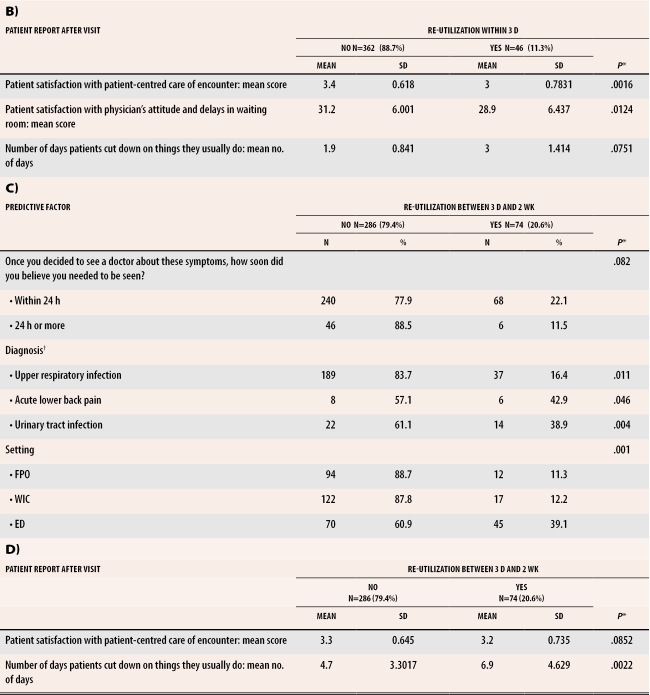

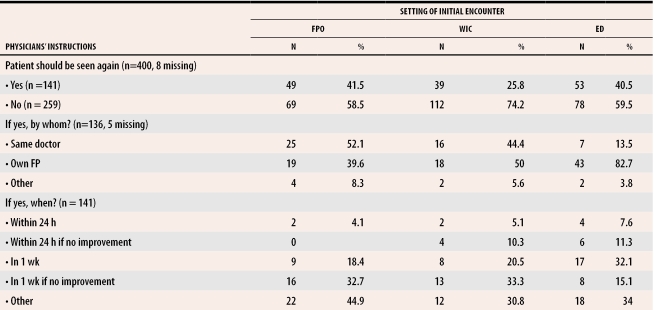

Table 1 presents factors associated at P <.10 with re-utilization of health services. The overall rate of early and later re-utilization of health services for the same episode of illness was 11.3% and 20.6%, respectively. Table 2 presents multivariable analysis of factors remaining in the logistic regression models after consideration and backward elimination of many hypothesized factors. The odds (after controlling for satisfaction with the patient-centred focus of the encounter) of early re-utilization were 6.5 times greater if the initial encounter was in an ED. After controlling for setting, the odds of early re-utilization were 1.7 times greater for every one-point decrease on the four-point scale used to measure satisfaction with the patient-centred focus of the encounter. For later re-utilization, the odds of re-utilization were 4.9 times greater if the initial encounter was in an ED. After controlling for setting, the odds of later re-utilization were 2.4 times greater if the initial diagnosis was UTI. Factors tested and found not to be significantly associated with rate of re-utilization were patients’ age, sex, responses to variety of questions assessing psychosocial factors (stress, social support, independence), and responses to questions asking opinions on health care.

Table 1. Univariable analysis of factors predictive of re-utilization of health care services for the same episode of minor acute illness (P< .10).

A) Factors associated with early re-utilization (within 3 days of initial encounter); B) Patients’ report after early visit; C) Factors associated with later re-utilization (between 3 days and 2 weeks after initial encounter); D) Patients’ report after later visit

ED—emergency department, FPO—family physicians’ office, SD—standard deviation, WIC—walk-in clinic.

*Factors tested and found not to be significantly associated with rate of re-utilization were age, sex, and subjects’ responses to a variety of questions regarding perceptions about their illness, social support, and opinions regarding health care.

†Diagnoses were treated as separate indicator variables.

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of factors predictive of re-utilization of health care for the same episode of minor acute illness

*Satisfaction with patient-centred care is a continuous variable on a scale of 1 to 4. The odds ratio represents the effect of each point decrease on the scale.

When asked why they re-used health care services, 58% of early re-users and 33% of later re-users stated that the presenting complaint either did not improve or got worse. This reason did not vary appreciably between settings. Patients whose initial encounter was in an ED often reported checking with their regular doctors and wanting, or being directed to, a second opinion.

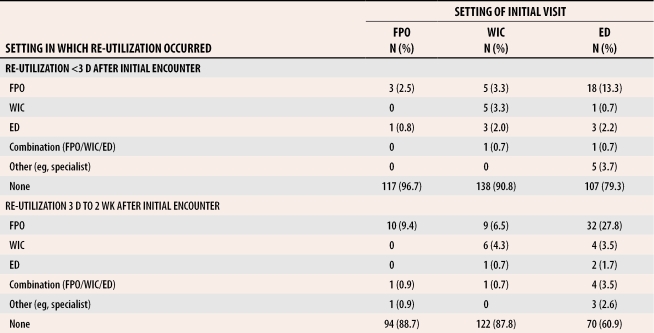

Table 3 presents subjects’ recall of whether they had been told they needed to be seen again. Return visit instructions given in FPOs and WICs were more likely to be contingent on whether patients’ conditions improved. In EDs, where return visit instructions were rarely contingent on improvement, patients were often told to follow up with visits to their own FPOs. Table 4 illustrates, by setting of initial encounter, where re-utilization occurred. Noteworthy is the high rate of visits to FPOs within 3 days of an initial encounter in an ED.

Table 3.

Patients’ reports of physicians’ instructions regarding return visit

Table 4.

Where re-utilization occurred

Direct costs of health care delivery

For cost analyses, complete data from both questionnaires on all study variables except follow up at 72 hours were available for 483 subjects. After exclusion of 17 subjects with two concomitant diagnoses, 20 subjects with diagnoses of insufficient sample size for stratification (low back pain or serous otitis media), and one subject with a suspected laboratory test coding error, a total of 445 subjects with one of six single diagnoses were available for analysis.

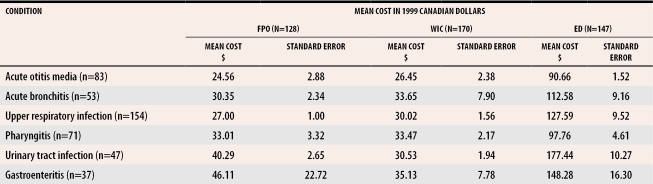

Table 5 presents the mean episode cost per patient by diagnosis and setting, with standard errors, as well as the cost differences, in dollars, with 95% confidence intervals. No significant differences were found between FPOs and WICs for any of the diagnoses studied, but ED settings were significantly more costly to the MOHLTC for all diagnoses studied.

Table 5. Mean costs (standard error) by setting and condition.

Statistical significance was assessed after cost differences and confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a regression model; no statistically significant difference in cost was found between WICs and FPOs (CIs for the difference all include zero); all diagnoses had a statistically significant difference in cost between EDs and FPOs (all CIs for the differences excluded zero).

Post-hoc analysis of the components of cost found that the initial visit cost was the largest component of cost in all settings and that the initial visit cost was greatest for all diagnoses in EDs (P <.001). In sensitivity analyses that varied cost estimates used to estimate overall costs, the ED setting remained the most expensive. When overhead costs were assumed to be zero, EDs were still more expensive except for the diagnosis of gastroenteritis.

DISCUSSION

Factors associated with re-utilization

The finding that early re-utilization of services was greater for patients who were less satisfied with the patient-centred care of their initial encounters adds to a growing literature on benefits of patient-centred care. Such care has been shown to increase patients’ adherence to medical advice,17 reduce use of health care services,18,19 and improve patients’ health status.20,21

Our finding that re-utilization rates for those whose initial encounter was at a WIC were similar to rates among those whose initial encounter was in an FPO was unexpected. A higher unadjusted early re-utilization rate for WICs was not statistically significant after controlling for patients’ satisfaction with patient-centred care. We speculate that the univariable association was mediated through satisfaction, although, in a previous study, we demonstrated that a small difference in satisfaction between these settings was not statistically significant.15 There was no difference in later re-utilization rates between those initially seen in WICs and FPOs. Our WIC re-utilization rates are lower than those suggested by Bell and Szafran.10 Bell and Szafran, however, did a retrospective survey of patients in their own office and asked for recall of WIC use; therefore, their sample would be expected to overrepresent numerator events (re-utilization) and underrepresent the true denominator (all WIC users). Our longitudinal study followed patients prospectively after initial encounters in WICs; thus our denominator was known.

The findings of increased re-utilization among those whose initial encounter was in an ED might be explained by patient factors or system factors. A separate analysis of these data showed that people who sought care in EDs had perceptions of greater urgency. Thus, we might speculate that their increased re-utilization is because they are inclined to seek health care more quickly and more often than others. As well, part of the increase in re-utilization of services can be explained when attending ED physicians advise patients to see their own family physicians within a specified period.

It is important to note that our study did not examine “appropriateness” of re-utilization. Many return visits would be required for follow up. For example, a diagnosis of UTI often necessitates a subsequent visit for follow-up cultures. Therefore, we cannot assume that all re-utilization implies unnecessary duplication.

Direct costs of health care delivery

The costs of care to the MOHLTC for the acute minor illnesses studied were greatest when initial evaluation and treatment occurred in EDs. This difference was not merely attributable to increased re-utilization. In fact, consistent with results from US studies,3,11,22 the largest component of cost was the initial ED physician evaluation and overhead costs, which were greatest in EDs.

The similarity in cost between FPOs and WICs was surprising, given that US studies have shown that using an identified primary care clinician for the first visit in an acute episode is associated with a 62% reduction in ambulatory care expenditures.2 Our findings suggest that continuity of care is not the major influencing factor in costs associated with these illnesses in this population, even though continuity is desirable for reasons other than cost.23,24 Perhaps factors other than continuity, such as physician training or practice style, were the factors that truly influenced costs in the US study.2 In Canada, physicians working in FPOs and WICs have similar educational backgrounds and training.

Limitations

Possible sources of bias in our findings are severity of illness and differential loss to follow up, both of which could affect re-utilization patterns and costs of care. First, it is possible that ED patients had more severe manifestations of illness. In a separate analysis, we found that ED patients had higher perceived severity scores. Our cost-analysis findings are consistent across all diagnoses, however, and some would be expected to vary little in their severity and initial presentation.2 Second, subjects for whom we had incomplete study follow-up data could have had different re-utilization patterns and different follow-up costs than those for whom follow-up status is known.

General comments

Compelling reasons suggest that health care encounters for minor illness should occur in FPOs, thus ensuring continuity of care.23,25 There are recognized societal trends toward using WICs,5 however, and an acknowledged shortage of family physicians in many parts of Ontario. Our data suggest neither a substantial increase in re-utilization of health care after visits to WICs for common acute conditions nor an increase in cost attached to using WICs; therefore, we believe that economic arguments do not apply.

Attention should be focused on avoiding use of EDs for minor acute illness. In our prior studies, we found that patient satisfaction is lowest among those seen in EDs, despite the high quality of care.15 In this current study, after controlling for other variables, we have demonstrated that people visiting EDs incur higher first-visit costs and subsequently higher rates of re-utilization of health services. Efforts to reduce use of EDs for minor acute illness could take several directions. Strategies to increase the availability of settings other than EDs during overnight hours could be investigated and, where feasible, implemented. We might need to address, for individual patients, the reasons for the perceptions of urgency attached to minor illness and to identify coping mechanisms to deal with nonurgent health problems. In all health care settings, providers should strive for patient-centred care.

CONCLUSION

Our finding that initial encounters in EDs are associated with higher re-utilization rates and our finding that ED use is associated with higher costs provide further evidence that use of EDs for minor acute illness is undesirable. Our finding that satisfaction with patient-centred care is associated with lower re-utilization rates underscores the importance of patient-centred care, regardless of setting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Sangster and Karen Atkin for their assistance with data collection, Robert Michaels for assistance with database design and management, Larry Stitt of the Biostatistical Support Unit at the University of Western Ontario for assistance with statistical analysis, and Randy Welch of the London Health Sciences Centre for his invaluable assistance with case costing. Members of the Ontario Walk-in Clinic Study Research Team are Principal Investigators Drs Jan Barnsley and A. Paul Williams; Drs Alan Campbell, David Davis, Allan Detsky, Philip Ellison, Lutchmie Narine, and Eugene Vayda from the University of Toronto; Drs Brian Hutchison, Janusz Kaczorowski, and Gina Ogilvie from McMaster University; and Drs Judith Belle Brown, M. Karen Campbell, Stewart Harris, Truls Østbye (currently at Duke University in North Carolina), Moira Stewart, and Evelyn Vingilis from the University of Western Ontario.

Biographies

Dr Campbell is a Professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and of Paediatrics at the University of Western Ontario and is an Affiliated Scientist at the Lawson Research Institute and the Child Health Research Institute in London.

Dr Wulf Silver practises family medicine at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Mich.

Dr Hoch is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, of Psychiatry, and of Family Medicine at the University of Western Ontario and is an Affiliated Scientist at The Lawson Research Institute in London.

Dr Østbye is a Professor in the Department of Community and Family Medicine in Durham, NC.

Dr Stewart is a Professor in the Departments of Family Medicine and of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and is Director of the Centre for Studies in Family Medicine at the University of Western Ontario.

Dr Barnsley is an Associate Professor in the Department of Health Administration at the University of Toronto.

Dr Hutchison is a Professor in the Departments of Family Medicine and of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and is Director of the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA) at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr Mathews is an Assistant Professor of Health Policy/Health Services in the Division of Community Health of the Faculty of Medicine at Memorial University in St John’s, Nfld.

Ms Tyrrell is currently a Project Manager in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organizations with which they are affiliated.

References

- 1.Burnett MG, Grover SA. Use of the emergency department for non-urgent care during regular business hours. CMAJ. 1996;154:1345–1351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest CB, Starfield B. The effect of first-contact care with primary care clinicians on ambulatory health care expenditures. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker LC, Baker LS. Excess cost of emergency department visits for non-urgent care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1994;13:162–171. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.5.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:642–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkenhagen RH. Walk-in clinics. Medical heresy or pragmatic reality? [editorial] Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1879. 1879-83 (Eng), 1888-93 (Fr) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman G, Hjortdahl P. What future for continuity of care in general practice? BMJ. 1997;314:1870–1873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7098.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meditz RW, Manberg CL, Rosner F. Improving access to a primary care medical clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 1992;84:361–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rachlis V. Who goes to after-hours clinics? Demographic analysis of an after-hours clinic. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:266–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonberg E. Walk-in clinics: implications for family practice. CMAJ. 1991;144:631–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell NR, Szafran O. Use of walk-in clinics by family practice patients. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:507–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren BH, Isikoff SJ. Comparative costs of urgent care services in university-based clinical sites. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:523–528. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyrance PH, Himmelstein DV, Woolhandler S. US emergency department costs: no emergency. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1527–1531. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redelmeier DA, Fuchs VR. Hospital expenditures in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:772–778. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303183281107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellermann AL. Nonurgent emergency department visits: meeting an unmet need. JAMA. 1994;271:1953–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchison B, Østbye T, Barnsley J, Stewart M, Mathews M, Campbell MK, et al. Patient satisfaction and quality of care in walk-in clinics, family practices and emergency departments: The Ontario Walk-in Clinic Study. CMAJ. 2003;168:977–983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKinley RK, Manku-Scott T, Hastings AM, French DP, Baker R. Reliability and validity of a new measure of patient satisfaction with out of hours primary medical care in the United Kingdom: development of a patient questionnaire. BMJ. 1997;314:193–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7075.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–675. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart MA, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redelmeier DA, Molin JP, Tibshirani RJ. A randomised trial of compassionate care for the homeless in an emergency department. Lancet. 1995;345:1131–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;275:5110–5127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams RM. Distribution of emergency department costs. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:671–676. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrest CB, Starfield B. Entry into primary care and continuity: the effects of access. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1330–1336. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowling PT. Emergency department costs. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1866–1867. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hjortdahl P, Borchgrevink CF. Continuity of care: influence of general practitioners’ knowledge about their patients on use of resources in consultations. BMJ. 1991;303:1181–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6811.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]