Abstract

PROBLEM ADDRESSED

There is currently no peer-reviewed evidence-based memory aid that incorporates recommended prevention guidelines to direct family physicians during periodic health examination of adults.

OBJECTIVE OF PROGRAM

To devise a memory aid to guide primary care physicians during periodic health examination of adults that incorporates the most current evidence-based recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care and of the United States Preventive Services Task Force.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

This memory aid is a two-page easy-to-use form that lists evidence-based maneuvers for adults aged 21 to 64 that should be carried out during periodic health examinations. This article describes the form and discusses the evidence currently available for the maneuvers mentioned on the form. To validate the memory aid, results of qualitative assessment in one academic and 15 community settings are presented.

CONCLUSION

This user-friendly memory aid was developed to provide primary care physicians with rigorously evaluated guidelines in an accessible format for use during periodic health examination of adults.

Abstract

PROBLÈME À L’ÉTUDE

Il n’existe présentement aucun aide-mémoire fondé sur des preuves ou sur des articles ayant fait l’objet d’une évaluation externe qui fournisse au médecin de famille des directives éprouvées sur l’examen médical périodique de l’adulte.

OBJECTIF DU PROGRAMME

Créer à l’intention des médecins de première ligne un aide-mémoire pour l’examen médical périodique de l’adulte renfermant les plus récentes recommandations fondées sur des preuves émises par le Groupe de travail canadien sur les soins de santé préventifs et par le United States Preventive Services Task Force.

DESCRIPTION DU PROGRAMME

L’aide-mémoire est un document pratique de deux pages qui énumère, en fonction des preuves disponibles, les gestes devant faire partie de l’examen de santé périodique des adultes de 21 à 64 ans. Cet article décrit ce document et discute des preuves actuellement disponibles à l’appui des manœuvres proposées. Il présente aussi les résultats d’une évaluation qualitative du document effectuée dans un contexte académique et dans 15 établissements de pratique communautaire.

CONCLUSION

Cet aide-mémoire convivial a été créé pour procurer au médecin de première ligne des directives rigoureusement choisies et facilement disponibles devant le guider dans l’examen de santé périodique de l’adulte.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This project’s goal was to develop an evidence-based, user-friendly memory aid to guide family doctors during annual health examinations. Suggested maneuvers are based on the latest guidelines of the Canadian and American task forces on preventive health care.

In general, recommendations were based on the best available evidence (grade A or B), but when evidence was grade C or I, recommendations were based on the potential benefit to individual patients and the availability of tests.

When there was a conflict between Canadian and American guidelines, Canadian ones were chosen, unless the American ones were more recent. All items required to satisfy provincial billing requirements were included.

The form was tested in an academic and several community practices and, in general, was found to be well accepted.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Ce programme avait pour but de développer un aide-mémoire convivial fondé sur des données probantes devant guider le médecin de famille lors de l’examen médical annuel. Les manœuvres suggérés provenaient des plus récentes directives des groupes de travail canadiens et américains sur les soins de santé préventifs.

La plupart des recommandations reposaient sur les meilleures preuves disponibles (niveau A ou B); lorsque les preuves étaient de niveau C ou I, l’inclusion des recommandations dépendait des avantages potentiels pour le patient et de la disponibilité des tests.

En cas de désaccord entre les directives canadiennes et américaines, on choisissait les canadiennes, sauf si les américaines étaient plus récentes. Tous les éléments découlant des exigences de facturation des provinces étaient inclus.

L’aide-mémoire a été testé dans un milieu de pratique académique et dans plusieurs établissement de médecine communautaires; il a été généralement bien accueilli.

The goal of periodic health examinations of asymptomatic adults is to prevent morbidity and mortality by identifying modifiable risk factors and early signs of treatable disease. In 1980, the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination produced their first evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.1 The task force was renamed the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) in 1984. Studies suggest that the task force’s recommendations are not being fully implemented into everyday primary care practice.2-4 Undergraduate and postgraduate medical training programs advocate using the best available evidence in teaching and practising medicine. The intention is that the habit of using available evidence will continue into clinical practice. Currently, the approach to periodic health examinations varies from physician to physician.5

Evidence-based recommendations produced by the CTFPHC6 and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)7 have been rigorously evaluated with respect to validity, generalizability, and measurability in regard to primary health care.8 Although thorough, these recommendations exist in formats that are difficult for physicians to use during patient encounters.

Physicians are aware of the rationale for following evidence-based recommendations, and most are likely to attempt to incorporate them into practice. Although busy physicians might recall and do some preventive health care maneuvers during patient visits without reminders, as the number of items increases, they are less likely to remember them all.9 Studies have shown that chart reminders based on age- and sex-specific guidelines for preventive procedures improve performance during examinations9-11 and that physicians are more likely to implement CTFPHC guidelines if they have attended a workshop on them.12

To review the literature thoroughly, we searched MEDLINE using the search terms “evidence-based,” “office tool,” “preventative,” “periodic health examination,” “annual health examination,” and “physical health examination.”

Objective of program

The program aimed to create an efficient, easy-to-use memory aid that would remind family physicians of evidence-based maneuvers to use during periodic health examination of adults aged 21 to 64. Such an aid would offer family physicians rigorously evaluated task force recommendations in a format that would be easy to use in everyday practice.

Components of the memory aid

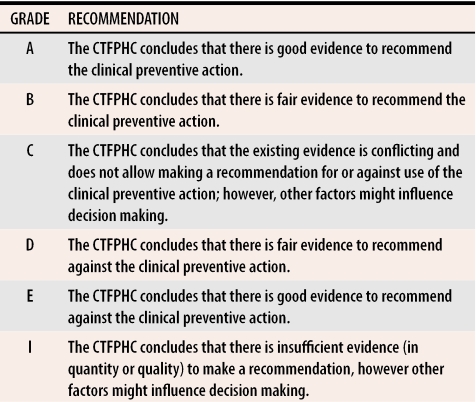

The format of this memory aid (Figure 1) addresses evidence-based maneuvers that have been shown to be effective in prevention and detection of disease and potential sources of injury. Recommendations used were those reviewed and published by the CTFPHC6 and the USPSTF.7 Grades of evidence used by the CTFPHC are listed in Table 1.6

Figure 1. Periodic Adult Health Maintenance Record.

Form shown is for male patients aged 21 to 64; forms for female patients and selected guidelines are available on the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s website at http://www.cfpc.ca/cfp.

Table 1.

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care grades of recommendations for specific clinical preventive actions

Source: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.6

Included were all maneuvers with good evidence (grade A, printed in bold type) and fair evidence (grade B, printed in italics) that were relevant for examination of those 21 to 64 years old. Maneuvers for which evidence was conflicting (grade C) or insufficient for making a recommendation (grade I) are printed in plain text. The decision to include a recommendation rated grade C or grade I depended on whether it was cost-effective and available (eg, homocysteine testing was excluded), whether emerging evidence would likely change the rating (eg, prostate-specific antigen testing, diabetes screening), whether it would benefit individual patients (eg, screening for suicide risk), and whether the maneuver could be performed easily in the office (eg, skin examination for moles).

In many instances, both Canadian and American task forces made recommendations on the same maneuver. If there was a conflict between the two, the Canadian recommendation was selected unless the American recommendation was more up-to-date. The exception to this was the recommendation on breast cancer screening. The USPSTF recommendation, although dated 2002, has inconclusive evidence for recommending mammography for women aged 40 to 49, even though its broad statement classifies it as a grade B recommendation. Despite being less current, the Canadian recommendation to offer mammography to women aged 50 to 69 at average risk of breast cancer was used. Recommendations from the USPSTF included in this memory aid were use of acetylsalicylic acid for prophylaxis against cardiovascular events; screening for hypertension; counseling about physical activity; screening for obesity; and screening for cervical, prostate, and skin cancer.

The form is divided into seven sections: Current Patient Concerns and Current Medications, Review of Systems, Social History, Past Medical History, Family History, and Physical Examination. These items and boxes that can be checked to indicate that a full functional inquiry and physical examination have been completed were included so that the information in the memory aid would meet provincial billing requirements for complete health assessments. Sections on Counseling Issues and Investigations and Treatment are also included to address other recommendations supported by evidence.

To keep the form user-friendly, space is provided for additional comments. Some maneuvers that require further explanation (eg, frequency of cervical cancer screening) are marked with a symbol (†) and described on page three of the memory aid. For reference, explanations on page three also show the grade of recommendation for each maneuver.

Current patient concerns and current medications.

Although this section is not based on evidence, it is intended to ensure a patient-centred approach. Patients are encouraged to voice their specific health concerns. As well, a review of their updated list of medications can be summarized in the space provided in this section.

Review of systems.

There are few evidence-based maneuvers in this section. The assessment of medical impairment for driving is included since screening questions for this assessment (ie, inquiries about vision and hearing impairment) are typically included in a review of systems (grade C). Inquiring about recent fractures is intended to screen for increased risk of osteoporosis (grade B). There is also a box that can be checked to indicate that a full functional inquiry was done beyond the recommended maneuvers. There is additional space for documenting symptoms.

Social history.

The evidence supports counseling about smoking cessation, alcohol intake, and current level of exercise, so inquiry into these matters is included in this section. Asking about drug use is intended to screen for high-risk behaviour (grade C) and might help physicians identify other comorbidity and high-risk addictive behaviour. Inquiring about sexual history is intended to screen for risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections. The intention is to guide decisions on further investigations. Asking about current employment is intended to screen for preventable work-related injuries, specifically noise-induced hearing loss (grade C).

Past medical history.

Cardiac risk factors should be reviewed and documented since there is evidence supporting prevention and treatment of cardiac-related diseases. Prior exposure to chickenpox of all adults and current status of immunization against rubella of all women capable of becoming pregnant should be documented to identify patients who require vaccinations. Inquiring about recent immigration is included to screen for HIV and tuberculosis in patients from countries known to have a high prevalence of these diseases.

Family history.

Specific inquiries into family history of cardiac disease, malignancies, and psychiatric disorders are included to help direct appropriate physical examination, investigations, and decisions about treatment.

Physical examination.

Page three of the form gives explanations of the maneuvers in this section. The right-hand column provides space for documenting findings of physical examinations that are pertinent to individual patients. There is also a box that can be checked to indicate that a full physical was completed, and there is additional space for documenting relevant findings.

Counseling

This section is subdivided into categories to assist physicians in selecting items that are relevant for individual patients. Further details of specific recommendations in the Counseling section are given on page three of the form.

Investigations and treatment

This section contains a checklist of items to be ordered or prescribed based on information gathered from the previous sections or as indicated by a patient’s age, sex, and smoking status. It is divided into four categories: Investigations, Treatment, Immunizations, and Other investigations. There is also a specific subsection for smokers. Decisions on treatment of hypertension should be based on established Canadian guidelines.13 The section on immunizations reflects the most current recommendations.14

Screening for hyperlipidemia using a fasting lipid profile is a grade B recommendation when there are cardiac risk factors and grade C in all other cases. As yet, no evidence indicates the optimal frequency of lipid screening. The CTFPHC, the USPSTF, and the Canadian Guidelines for the Management and Treatment of Dyslipidemias suggest that screening should be carried out every 5 years if patients have no cardiac risk factors and every 1 to 2 years if patients develop cardiac risk factors.15-17

To determine the frequency of diabetes screening, we referred to the most current clinical practice guidelines.18 These recommendations come from a consensus statement based on expert opinion because no long-term data currently support particular screening practices for type 2 diabetes. Despite only a consensus grading, we included screening with fasting glucose measurements because of the increasing prevalence and morbidity of type 2 diabetes in our society and because we anticipate that new evidence will likely support more aggressive diabetes screening. Space is available on the right-hand side of this section for documenting other treatments and investigations that are indicated by individual patient encounters but not supported by evidence.

Summary and plan

Space is provided for final comments and follow-up plans.

Evaluation

The original draft of this memory aid was evaluated at the Hotel Dieu Family Medicine Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont, and at several community practices in the Kingston area. During a 1-month trial, this form replaced the standard annual health examination form previously used at the academic centre and was used twice by each of 15 physicians in community practices. A feedback sheet was attached to the form for comments and suggestions.

More than 87% of respondents made positive remarks about the memory aid, stating that it was “useful” and helped annual health examinations to be “streamlined” and “efficient.” Common suggestions included having separate forms for men and women, including more space for comments, creating a version for electronic medical records, and providing further clarification of specific recommendations. Several respondents asked how a patient-centred approach could be combined with using the memory aid.

As a result of the useful feedback, many changes were made to the format and specific recommendations clarified. Based on the positive responses, the academic centre has endorsed use of this memory aid by residents and attending staff for all annual health examinations of adults aged 21 to 64. In addition, most of the community physicians found the form innovative and useful, and more than 65% said they would like to continue using the memory aid. Community physicians less likely to incorporate the memory aid into practice were those nearing retirement and those who preferred to wait for a version suitable for electronic medical records.

Discussion

Our MEDLINE search failed to identify any published, peer-reviewed office memory aids for use during periodic health examination of adults that incorporated recommended guidelines for history, physical examination, counseling, and treatment. Charts and tables were available, however, on both the Canadian and American task force websites6,7 and on the American Academy of Family Physicians’ website.19 These charts and tables contain mostly summaries of recommendations and are presented as lists rather than in a format that could be used during an annual health examination.

Two preventive health checklist forms were identified.20,21 One of these screening tools had not been validated in a trial, and because the authors chose to focus on creating a summary sheet that would withstand the scrutiny of a provincial chart audit, it lacked many recommended evidence-based maneuvers.20 Although both forms had some similarities to our memory aid, their formats were different. Both included only CTFPHE recommendations, many of which are out-of-date compared with some USPSTF recommendations.

One limitation of our memory aid is that, because evidence and recommendations are continually evolving, it must be updated periodically. To indicate how current our form’s content is, we have indicated the latest revision date at the foot of each page. The process of reviewing new evidence in order to update our memory aid will occur only if we can obtain additional research funding. We hope to obtain the intellectual property rights to the memory aid to ensure its authenticity and the consistency of future updates.

Some maneuvers are often included in clinical encounters but are not, and might never be, studied using high-quality, randomized controlled trials. Good clinical evidence for these maneuvers might be impossible, impractical, or too expensive to obtain. Hence, it might be difficult to develop grade A or B recommendations for maneuvers that are routinely included in many settings. Therefore, physicians must continue to rely on their clinical judgment for including or excluding interventions during individual patient encounters. Our memory aid was not created to replace clinical judgment but to assist physicians in recalling recommended evidence-based maneuvers.

The most common criticism of the memory aid pertained to the lack of space in certain sections and the feeling of going through a checklist rather than providing patient-centred care. To address the lack of space, we hope in the future to incorporate this memory aid into a format compatible with electronic medical records. In an electronic format, space can be added and tailored to fit physicians’ needs. With respect to the second issue, we have included a section at the beginning of the form suggesting that physicians discuss patients’ primary health concerns first. We hope this will encourage a patient-centred approach to periodic health examinations so that patients do not feel their physicians have their own agenda or checklist to get through. If time becomes short after addressing patients’ concerns, the maneuvers suggested in other sections of the memory aid can be completed during future visits.

As with all guidelines, the recommendations in the memory aid reflect the best understanding at the time of publication. They should be followed, however, with the understanding that ongoing research will likely result in new knowledge and updated recommendations.

Conclusion

This memory aid was devised to incorporate evidence-based recommendations from the CTFPHE and the USPSTF into a preventive care form. The intention was to provide a user-friendly tool for primary care physicians that incorporates rigorously evaluated guidelines in a format that is accessible during periodic health examinations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mike Sylvester for supervising this project and giving us support and advice along the way and the Department of Family Medicine at Queen’s University for their positive feedback and continuing support for this project.

Biography

Dr Milone practises family medicine anesthesia, and Dr Lopes Milone practises family medicine, both at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont.

References

- 1.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Periodic health examination monograph: report of the Task Force to the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health. Catalogue no. H39-3/1980E. Ottawa, Ont: Health Services and Promotion Branch, Department of National Health and Welfare; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith HE, Herbert CP. Preventive practice among primary care physicians in British Columbia: relation to recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. CMAJ. 1993;149:1795–1800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchison BG, Woodward CA, Norman GR, Abelson J, Brown JA. Provison of preventive care to unannounced standardized patients. CMAJ. 1998;158:185–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman A, Pimlott N, Naglie G. Preventive care for the elderly. Do family physicians comply with recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care? Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:350–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathe R. The complete physical. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(7):1439. 1439,1443-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Evidence-based clinical prevention. London, Ont: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2000. [cited 2005 November 3]. Available at: http://www.ctfphc.org. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Preventive Services Task Force. Preventive services. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [cited 2005 November 3]. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham RP, James PA, Cowan TM. Are clinical practice guidelines valid for primary care? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:949–954. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheney C, Ramsdell JW. Effect of medical records’ checklists on implementation of periodic health measures. Am J Med. 1987;83:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald CJ, Hui SL, Smith DM. Reminders to physicians from an introspective computer medical record: a two-year randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:130–138. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen DI, Littenberg B, Wetzel C. Improving physician compliance with preventive medicine guidelines. Med Care. 1982;20:1040–1045. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaulieu MD, Rivard M, Hudon E, Beaudoin C, Saucier D, Remondin M. Comparative trial of a short workshop designed to enhance appropriate use of screening tests by family physicians. CMAJ. pp. 1241–1246. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Canadian Hypertension Society. The 2003 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension. Toronto, Ont: Canadian Hypertension Society; 2005. [cited 2005 November 3]. Available at: http://www.hypertension.ca/recommendations2003_va.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Canadian immunization guide. 6th ed. Ottawa, Ont: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fodor JG, Frohlich JJ, Genest JJ, Jr, McPherson PR. Recommendations for the management and treatment of dyslipidemia. Report of the Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias. CMAJ. 2000;162:1441–1447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, Smith S, Jr, Fuster V. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 1999;100:1481–1492. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.13.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson P, D’Agostino R, Levy D, Belanger A, Silbershatz H, Kannel W. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. 2003 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Canadian Diabetes Association. Can J Diabetes. 2003;27(Suppl 2):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Family Physicians. Summary of policy recommendations for periodic health examinations. Revision 5. 6. Leawood, Kan: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2004. [cited 2005 November 3]. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/exam.xml. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schabort I, Hilts L, Lachance J, Mizdrak N, Schwartz M. Charting made easier and faster [letter]. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:535–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubey V, Mathew R, Glazier R, Iglar K. The evidence-based preventive care checklist form. Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2004. [cited 2005 November 3]. Available at: http://www.cfpc.ca/English/cfpc/communications/health%20policy/Preventive%20Care%20Checklist%20Forms/Intro/default.asp?.s=1. [Google Scholar]