Abstract

The NS3 (dengue virus non-structural protein 3) serine protease of dengue virus is an essential component for virus maturation, thus representing an attractive target for the development of antiviral drugs directed at the inhibition of polyprotein processing. In the present study, we have investigated determinants of substrate specificity of the dengue virus NS3 protease by using internally quenched fluorogenic peptides containing Abz (o-aminobenzoic acid; synonymous to anthranilic acid) and 3-nitrotyrosine (nY) representing both native and chimaeric polyprotein cleavage site sequences. By using this combinatorial approach, we were able to describe the substrate preferences and determinants of specificity for the dengue virus NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease. Kinetic parameters (kcat/Km) for the hydrolysis of peptide substrates with systematic truncations at the prime and non-prime side revealed a length preference for peptides spanning the P4–P3′ residues, and the peptide Abz-RRRRSAGnY-amide based on the dengue virus capsid protein processing site was discovered as a novel and efficient substrate of the NS3 protease (kcat/Km=11087 M−1·s−1). Thus, while having confirmed the exclusive preference of the NS3 protease for basic residues at the P1 and P2 positions, we have also shown that the presence of basic amino acids at the P3 and P4 positions is a major specificity-determining feature of the dengue virus NS3 protease. Investigation of the substrate peptide Abz-KKQRAGVLnY-amide based on the NS2B/NS3 polyprotein cleavage site demonstrated an unexpected high degree of cleavage efficiency. Chimaeric peptides with combinations of prime and non-prime sequences spanning the P4–P4′ positions of all five native polyprotein cleavage sites revealed a preponderant effect of non-prime side residues on the Km values, whereas variations at the prime side sequences had higher impact on kcat.

Keywords: dengue virus, fluorescence, 3-nitrotyrosine, dengue virus non-structural protein 3 (NS3) serine protease, polyprotein, substrate specificity

Abbreviations: Abz, o-aminobenzoic acid; Boc, t-butoxycarbonyl; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Fmoc, fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl; NS3, dengue virus non-structural protein 3; t-Bu, t-butyl; Trt, trityl; Tyr(3-NO2) or nY, 3-nitrotyrosine

INTRODUCTION

The NS2B (dengue virus non-structural protein 2B)–NS3 two-component protease of dengue virus catalyses the cleavage of the viral polyprotein precursor in the non-structural region at the NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3, NS3/NS4A and NS4B/NS5 sites [1–4]. Additional proteolytic cleavages within the viral capsid protein, NS2A, NS4A and within a C-terminal part of NS3 itself were previously reported in the literature [5–8] (Figure 1). Optimal activity of the NS3 protease (flavivirin, EC 3.4.21.91) is essential for the maturation of the virus, thus making this enzyme a promising target for the development of protease inhibitors that are eventually useful as antiviral drugs for the treatment of severe diseases caused by dengue virus (for reviews see [9–11] and references therein). Based on sequence comparisons with known proteases, a serine protease domain was originally identified in the N-terminal region of the 69 kDa NS3 protein [2] and the minimum sequence that supports protease activity was mapped to 167 residues of NS3 [12]. The C-terminal two-thirds of the dengue virus NS3 protein are associated with the enzymatic functions of a nucleoside triphosphatase, RNA helicase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase [13–15]. Analysis of polyprotein processing had established that the cleavage sites for the NS3 protease consist of paired basic residues (arginine or lysine) at the P1 and P2 positions followed by a short-chain amino acid (glycine, alanine or serine) at the P1′ position. In contrast with the trans cleavage sites, the intramolecular cis cleavage site NS2B/NS3 contains a glutamine residue at the P2 position [3,16–18].

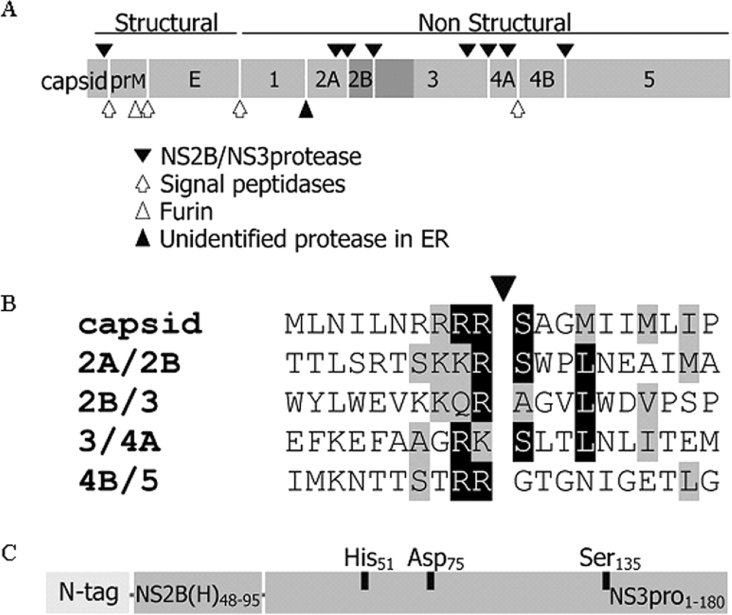

Figure 1. Diagram of the viral polyprotein precursor and the NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease construct of dengue virus serotype 2 and sequences of the viral polyprotein sites recognized by the NS2B–NS3 protease.

(A) Proteolytic processing sites in the viral polyprotein. Known cleavages in the regions of the structural and non-structural proteins that are mediated by host cell proteases and the virus-encoded NS2B–NS3 protease are shown. prM denotes the precursor of the viral membrane protein. The region of the NS2B and NS3pro proteins is shaded in dark grey. The recombinant protease NS2B(H)–NS3pro as generated by splicing-by-overlap extension PCR contains the N-terminal polyhistidine tag for purification purposes, the conserved activation domain of NS2B (residues 48–95) followed by residues 121–130, and 180 N-terminal residues of the dengue virus NS3 protein. (B) Sequence alignment of the polyprotein cleavage junctions recognized by the NS2B–NS3 protease. Identical residues are shaded in black and conserved residues are shaded in light grey. The triangle above the sequences denotes the scissile bond cleaved by the protease. Residues of the catalytic triad His51, Asp75 and Ser135 are shown in (C).

The presence of the 14 kDa activating protein NS2B was shown to be a prerequisite for optimal activity of the NS3 serine protease with synthetic peptide substrates and cloned polyprotein precursors [1,16]. Mutagenesis studies had demonstrated that a central hydrophilic domain of 40 residues within NS2B is essential for protease activation [19] and that individual residues within this core segment are involved in binding of the cofactor to the NS3 protease moiety [20]. The result of this structural activation is probably a conformational rearrangement of the catalytic residues (His51, Asp75 and Ser135), together with subsite residues rearrangement, which facilitates substrate binding and/or optimizes proton exchange during catalysis [21,22]. The formation of a catalytically active non-covalent complex is observed as a result of autoproteolytic in cis cleavage at the NS2B/NS3 site with recombinant constructs containing the NS3 protease domain fused to the NS2B activation core sequence [NS2B(H)–NS3pro] [23]. The three-dimensional structure of the NS3 protease domain (NS3pro) has been resolved by X-ray crystallography and shows that the enzyme exhibits a folding pattern that belongs to the class of trypsin-like serine proteases [24].

Specificity studies with synthetic peptides mimicking native polyprotein sequences have identified preferences for the cleavage of individual polyprotein processing sites [25–28]. Activity assays using chromogenic hexapeptides had shown that a substrate peptide based on the NS2A/NS2B site was most efficiently cleaved by a recombinant protease incorporating a cleavage-resistant linker inserted between the NS2B activation domain and the protease {CF40-gly-NS3pro [dengue virus protease domain of NS3 fused to a 40-amino-acid-residue core sequence of NS2B by a glycine linker (Gly)4Ser(Gly)4]}, whereas the peptide based on the NS2B/NS3 site was the poorest substrate for the NS3 protease [27]. Kinetic analysis of the NS2B(H)–NS3pro protein with dansylated dodecamer peptides indicated preferences for substrates representing the NS3/NS4A and NS4B/NS5 sites, while the peptide derived from the NS2B/NS3 site was cleaved with lowest efficiency [26]. Molecular models based on the three-dimensional structure of the NS3 protease domain as obtained from X-ray diffraction analysis had suggested the presence of a relatively small and shallow substrate-binding pocket, with enzyme–substrate interactions not extending beyond the P2 and P2′ positions in the absence of the NS2B cofactor [24]. Li et al. [28] had recently described a functional substrate profiling of the P1–P4 and P1′–P4′ regions of the CF40-gly-NS3pro185 proteases from all dengue virus serotypes and have shown that the four enzymes appear to share very similar substrate specificities. This work has conclusively demonstrated that the conserved subsite preferences of the dengue virus NS3 protease are dibasic residues at the P1 and P2 positions, basic or aliphatic residues at P3 and P4 and small or polar residues at P1′. The finding that residues at P3 and P4 also contributed significantly to ground-state binding provided additional evidence for enzyme–substrate interactions that extend beyond the S2 to S2′ subsites. The substrate-binding pocket of the NS3 proteases from four dengue virus serotypes consists of a number of highly conserved residues within the S1–S4 region and the theoretical molecular interactions with the substrate are largely consistent with the specificities observed in functional profiling experiments [28].

It was shown recently that the dengue virus NS3 protease displays marked sensitivity to competitive inhibition by peptides corresponding to the N-terminal cleavage products of the polyprotein sites and specificities observed for binding of product inhibitors implied the existence of an expanded substrate-binding site in the presence of NS2B(H) [29]. In addition, a preference of the NS3 protease for basic residues at the P3 and P4 positions had emerged from competition assays and molecular docking calculations. In this context, it is interesting to note that the natural cleavage site sequences of dengue virus type 2 display very little similarity in the P3–P6 region. However, the capsid, NS2A/NS2B and NS2B/NS3 sites feature basic residues at the P3 position (arginine and lysine respectively), and at the P4 position, arginine is present in the capsid protein and lysine is present at the NS2B/NS3 cleavage site.

Previous studies have used synthetic peptide substrates incorporating either fluorescent leaving groups such as AMC (7-amino-4-methylcoumarin) or chromogenic reporter groups (p-nitroanilides) at the P1′ position of the substrate peptide [27,28,38]. Since these substrates do not allow for an extension of the test sequence to the prime side (C-terminal to the scissile bond), information on prime side preferences is largely limited to observations with natural polyprotein substrates and does not provide kinetic constants for enzymatic efficiency. Moreover, these substrates exhibited poor reactivities with the dengue virus NS3 protease and were probably not optimized with regard to length and sequence.

In order to gain insight into the subsite preferences of the dengue virus NS3 protease, we have designed libraries of internally quenched synthetic peptides with systematic variations of the peptide length and the sequences around the scissile bond. These substrates would permit the determination of numerical specificity constants (kcat/Km) and therefore a comparative analysis of preferences for substrate recognition. We have also performed a systematic approach to evaluate the contribution of prime side sequences to cleavage efficiency by generating chimaeric substrate peptides in which prime side sequences of native polyprotein junctions were recombined. In addition, requirements for the prime side residue were probed by generating a series of alanine replacements at the P1′ to P4′ residues.

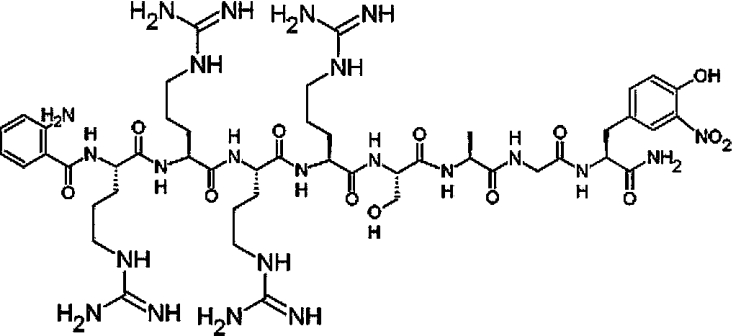

In the present paper, we demonstrate (i) that the preferred substrate size for the dengue virus NS3 protease encompasses the residues from P4 to P3′, (ii) that the presence of basic residues at the P3 and P4 positions significantly promotes reactivity and (iii) that serine is the preferred P1′ residue. Based on these studies, a highly efficient novel substrate (kcat/Km=11087 M−1·s−1), comprising a modified native capsid protein cleavage sequence, was found (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structure of the most efficient fluorogenic peptide (Abz-RRRR-SAGnY-amide) for the NS2B–NS3 protease found herein.

As seen, the donor-quencher groups are anthranilic acid at the N-terminus and 3-nitrotyrosine at the C-terminus.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Active dengue virus protease NS2B(H)–NS3pro was expressed in Escherichia coli and refolded after purification as described previously [20].

Forty-nine intramolecularly quenched substrates, based on the Abz (o-aminobenzoic acid)/3-nitrotyrosine [Tyr(3-NO2) or nY] pair, were prepared by solid-phase synthesis using an automated multiple peptide synthesizer (MultiPep; Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments AG, Koeln, Germany) (Table 1). Reagents were purchased from Fluka (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, U.S.A.), Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland) and Novabiochem (Calbiochem-Novabiochem AG, Laufelfingen, Switzerland). The following amino acid derivatives were used in synthesis: Fmoc-Ala-OH (where Fmoc is fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl), Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH (where Pbf is 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulphonyl), Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OH (where Trt is trityl), Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH (where Boc is t-butoxycarbonyl), Fmoc-Met-OH, Fmoc-Phe-OH, Fmoc-Pro-OH, Fmoc-Ser(t-Bu)-OH (where t-Bu is t-butyl), Fmoc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH, Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Val-OH, Fmoc-Tyr(3-NO2)-OH [where Tyr(3-NO2) is 3-nitrotyrosine] and Boc-Abz-OH. PyBOP (benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate) was used as an activating reagent and Rink Amide MBHA resin (capacity 0.64 mmol/g) as a polymeric support [Rink Amide MBHA resin is 4-(2′,4′-dimethoxyphenyl-Fmoc-aminomethyl)-phenoxyacetamido-norleucyl-4-methylbenz-hydrylamine resin]. Peptides were characterized by HPLC and their structures were confirmed by MS. Analytical HPLC was performed on a Waters (Milford, MA, U.S.A.) system (Millenium32 workstation, 2690 Separation Module, 996 Photodiode Array Detector) equipped with a Vydac RP C18 90 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) reversed-phase column (2.1 mm×250 mm). Purity of raw peptides according to HPLC was above 80%, and they were used for kinetic experiments after freeze-drying. Molecular mass measurements were performed on a PerkinElmer (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) instrument PE SCIEX API 150EX with turboionspray ion source. Freeze-drying was carried out at 0.01 bar (1 bar=100 kPa) on a Lyovac GT2 freeze-dryer (Steris Finn-Aqua, Tuusula, Finland) equipped with a Trivac D4B (Leybold Vacuum GmbH, Cologne, Germany) vacuum pump and a liquid nitrogen trap. All other chemicals were reagent grade from Sigma.

Table 1. Sequences of peptides used for activity studies with the NS2B–NS3pro protease.

(a) Peptides where P5–P1 are derived from cleavage site NS3/NS 4A and P1′–P4′ from cleavage sites NS3/NS4A, NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3, NS4B/NS5 or the capsid cleavage site. (b) Peptides where P4–P1 are derived from cleavage sites NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3 or NS4B/NS5 and P1′–P4′ from NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3 or NS4B/NS5, NS3/NS4A or the capsid cleavage site. (c) Peptides where P5–P1 or P4–P1 are derived from the capsid cleavage site and P1′–P4′ from the same cleavage site or cleavage sites NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3, NS3/NS4A or NS4B/NS5. nY, 3-nitrotyrosine. (Note that some peptides are truncated in their non-prime and/or prime ends). Dots in the sequences indicate the location of the scissile bond.

| (a) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Sequence | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Abz | F | A | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 |

| 2 | Abz | A | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | |

| 3 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 4 | Abz | A | R | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 5 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | W | P | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 6 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | A | G | V | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 7 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | G | T | G | N | nY | NH2 | ||

| 8 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 9 | Abz | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | |||

| 10 | Abz | R | K | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||||

| 11 | Abz | F | A | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | nY | NH2 | |

| 12 | Abz | F | A | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 13 | Abz | F | A | A | G | R | K | . | S | nY | NH2 | |||

| 14 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | T | nY | NH2 | |||

| 15 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | L | nY | NH2 | ||||

| 16 | Abz | A | G | R | K | . | S | nY | NH2 | |||||

| 17 | Abz | G | R | K | . | S | nY | NH2 | ||||||

| 18 | Abz | R | K | . | S | L | nY | NH2 | ||||||

| 19 | Abz | R | K | . | S | nY | NH2 | |||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||||||

| Number | Sequence | |||||||||||||

| 20 | Abz | S | K | K | R | . | S | W | P | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 21 | Abz | S | K | K | R | . | A | G | V | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 22 | Abz | S | K | K | R | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 23 | Abz | S | K | K | R | . | G | T | G | N | nY | NH2 | ||

| 24 | Abz | S | K | K | R | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 25 | Abz | K | K | Q | R | . | A | G | V | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 26 | Abz | K | K | Q | R | . | S | W | P | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 27 | Abz | K | K | Q | R | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 28 | Abz | K | K | Q | R | . | G | T | G | N | nY | NH2 | ||

| 29 | Abz | K | K | Q | R | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 30 | Abz | S | T | R | R | . | G | T | G | N | nY | NH2 | ||

| 31 | Abz | S | T | R | R | . | S | W | P | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 32 | Abz | S | T | R | R | . | A | G | V | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 33 | Abz | S | T | R | R | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 34 | Abz | S | T | R | R | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| (c) | ||||||||||||||

| Number | Sequence | |||||||||||||

| 35 | Abz | N | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | |

| 36 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 37 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | A | A | G | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 38 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | A | M | nY | NH2 | ||

| 39 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | G | A | nY | NH2 | ||

| 40 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | G | nY | NH2 | |||

| 41 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | A | nY | NH2 | ||||

| 42 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | nY | NH2 | |||||

| 43 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | A | nY | NH2 | |||||

| 44 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | G | nY | NH2 | |||||

| 45 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | nY | NH2 | ||||||

| 46 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | L | T | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 47 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | S | W | P | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 48 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | A | G | V | L | nY | NH2 | ||

| 49 | Abz | R | R | R | R | . | G | T | G | N | nY | NH2 | ||

Determination of catalytic parameters

Hydrolysis of the peptide substrates was followed on a POLAStar OPTIMA 96-well plate reader (BMG Labtech GmbH, Offenburg, Germany), at 37 °C. Cleavage of the substrate as a function of time was followed by monitoring the emission at 420 nm on excitation at 320 nm, and the initial velocity was determined from the linear portion of the progress curve prior to 10% substrate depletion. Individual catalytic parameters Km and kcat were determined by direct fitting of v0 versus S0 values assuming Michaelis–Menten kinetics, v=Vmax [S]/[S]+Km, using nonlinear regression. Cleavage reactions contained in a final volume of 100 μl 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 9.0) and 20% (w/v) glycerol. Enzyme concentration was varied from 35 to 400 nM depending on the substrate used. At least eight points of substrate concentrations were used ranging from 0.1 to 5 Km. Standard curves were obtained by using the signal of the N-terminal Abz-containing cleavage fragment corresponding to each individual substrate and were converted to molar concentrations of the hydrolysed product. Inner filter effects were corrected as previously described [30]. All determinations were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.01 software. At least three independent experiments were carried out for each set of data points and the standard deviations of the reported numerical constants were below 10%.

RESULTS

Dengue virus NS3 protease subsite interactions

In order to overcome the limitations associated with the previously described NS3 protease substrates [27,28,38], we have designed libraries of peptides based on intramolecular quenching. These substrates contain a fluorogenic group (Abz) and a quenching group (3-nitrotyrosine), which are positioned at opposite ends of the substrate molecule and their proteolytic separation results in fluorescence release. An obvious advantage of this strategy is that the actual peptide bond of a protein substrate is represented in these compounds and that the test sequence can be extended to both sites of the scissile bond. A potential disadvantage of these substrates is the possible contribution of the reporter groups to binding, which may result in lower Km (app) values.

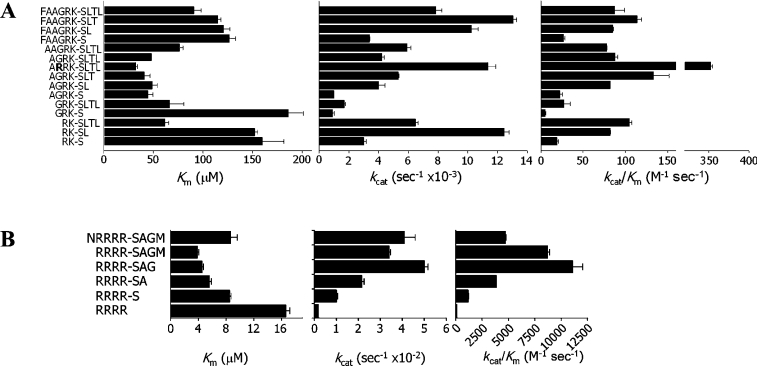

In a first step towards the identification of a minimal substrate size for the dengue virus NS3 protease, we used the decapeptide Abz-FAAGRK-SLTLnY-amide (1) (where nY is 3-nitrotyrosine) encompassing residues P6–P4′ of the NS3/NS4A cleavage site as a starting structure. Earlier studies had suggested that peptides based on the NS3/NS4A polyprotein site were efficiently cleaved by the NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease when compared with substrates that were based on the remaining cleavage junctions [25,27]. Autoproteolytic cleavage of the NS2B(H)–NS3pro construct at the NS2B/NS3 site leads to the formation of an enzymatically active non-covalent complex and complete cleavage of the precursor was verified by SDS/PAGE prior to activity assays [23]. We have further analysed the effects of systematic truncations in the non-prime and prime side regions by using six frames of peptides (based on the sequence length of the non-prime side region): FAAGRK (peptides 1, 11–13), AAGRK (2), AGRK (3, 14–16), GRK (9, 17), RK (9, 18, 19) and RRRR (36, 40–42, 45), the latter derived from the cleavage site sequence of the virus capsid protein. Kinetic parameters for this family of peptides are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of internally quenched synthetic peptides by the NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease.

(A) Substrate length mapping by using peptides with truncations in the prime and non-prime side region. (B) Contribution of prime side residues. Amino acid sequences shown for (A) and (B) represent the central part of the substrate molecule (i.e., the Abz group at the N-terminus and 3-nitrotyrosineamide residue at the C-terminus included in all molecules are not shown). For each sample peptide, Km, kcat and the specificity constant kcat/Km are shown. In addition to substrate sequences based on the native polyprotein cleavage sites, kinetic constants are shown for the peptide Abz-ARRK-SLTLnY-amide (4) containing an arginine residue at the P3 position.

Removal of prime side residues within the FAAGRK and AGRK derived peptides appeared to mainly influence kcat values, whereas Michaelis–Menten equilibrium constants were less affected. This is particularly evident in the AGRK frame (peptides 3–8), where Km values are almost identical and catalytic efficiencies expressed as kcat/Km vary nearly 6-fold from 22.7 M−1·s−1 (Abz-AGRK-SnY-amide, 16) to 130.7 M−1·s−1 (Abz-AGRK-SLTnY-amide, 14). Within this frame of substrates, catalytic rates are modulated approx. 5-fold by the residues of the prime side region as can be seen from a comparison between Abz-AGRK-SnY-amide (16, kcat=0.001 s−1) and Abz-AGRK-SLTnY-amide (14, kcat=0.005 s−1).

Not unexpectedly, peptides with shorter non-prime sides such as Abz-GRK-SLTLnY-amide (9) and Abz-GRK-SnY-amide (17) display much larger variations in their Km and kcat values. For these substrates with short suboptimal sequences in the non-prime side region, we would predict that the contribution of prime side residues to cleavage efficiency may become more significant, thus indicating effects of these positions on both substrate binding and acylation kinetics. In line with this interpretation, the observed Km value for the peptide Abz-RK-SLTLnY-amide (10) is 3.2-fold lower and kcat/Km is approx. 8.3-fold higher than the kinetic constants for the peptide Abz-RK-SnY-amide (19). Within the RRRR frame of the substrates tested, the peptide Abz-RRRR-SAGnY-amide (40) had a Km of 4.5 μM and the highest kcat/Km (11087 M−1·s−1) within this set of sample peptides (Figure 3). The contribution of the P3 residue to the reactivity was tested by introducing an arginine residue, which resulted in the peptide Abz-ARRK-SLTLnY-amide (4). Compared with the parent sequence, Abz-AGRK-SLTLnY-amide (3), this substrate yielded an approx. 4-fold higher kcat/Km value, a finding which would support an important role for a basic residue at this position.

The results presented here are also suggestive of preferred subsite binding in the S1′ to S3′ region, since all peptides incorporating all three prime side residues P1′ to P3′ had demonstrated the highest catalytic efficiencies within their group of substrates. This notion is particularly supported by the kinetic data for substrates based on the RRRR frame, where a 2-fold decrease in Km is paralleled by a 5-fold increase in rate constants between Abz-RRRR-SnY-amide (42) and Abz-RRRR-SAGnY-amide (40).

From the analysis of substrate preferences within the non-prime region, it is likely that a sequence ranging in length from P1 to P4 would satisfy most of the binding interactions with the NS3 protease as can be inferred from the 3-fold lower Km values of substrates of the AGRK frame when compared with the substrates of the FAAGRK frame. It is interesting to note that the peptide substrates with a pentameric sequence in the non-prime region, Abz-AAGRK-SLTLnY-amide (2) and Abz-NRRRR-SAGMnY-amide (35), display slightly higher catalytic rates when compared with the substrates with four non-prime residues. However, this gain in catalytic efficiency seems to be outweighed by a substantial decrease in binding affinities. Taken together, these results would support the conclusion that the substrate size preferred by the dengue virus NS3 serine protease is a heptapeptide spanning the P4–P3′ residues.

Chimaeric peptides

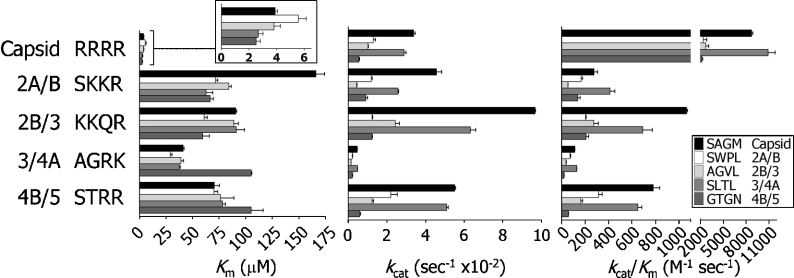

The dengue virus NS2B/NS3 protease complex recognizes four cleavage sites in the non-structural region of the polyprotein precursor and one cleavage site in the sequence of the capsid protein. The sequences flanking the P2 and P1′ positions of the cleavage junctions display very little similarity and we hypothesized that variations in these sequences would be determinants of processing efficiency and thereby could affect the order of cleavage events in the native polyprotein precursor. We have addressed the question of relationships within the region ranging from P4 to P4′ by the synthesis of a set of 16 chimaeric peptides representing combinations of non-prime and prime side sequences derived from the native dengue virus polyprotein cleavage sites (i.e. peptides 21–24, 26–29, 31–34 and 46–49). The patterns of activity disclosed by using these sample substrates suggest a larger influence of the non-prime side sequences on Km values, whereas variations in the prime side region appeared to have greater effects on rate constants. The most efficiently hydrolysed substrates were peptides that contain the tetrabasic non-prime side sequence RRRR of the capsid protein (Figure 4). Within this group of substrates, the lowest Km values (2.5–5.5 μM) were observed and the highest catalytic efficiency was produced by a capsid–NS4A hybrid, Abz-RRRR-SLTLnY-amide (peptide 46), with a kcat/Km of 10870 M−1·s−1. Within all groups of substrates, the prime side sequences had greater impact on kcat values, leading to substantial variations in catalytic efficiencies (Figure 4). A 10-fold variation in kcat was observed within the NS2A group between the peptides Abz-SKKR-AGVLnY-amide (21, 0.27 min−1) and Abz-SKKR-SAGMnY-amide (24, 2.7 min−1) and the lowest rate constants were found in the NS3 group, which also contains the poorest substrate identified within this series of substrates, Abz-AGRK-GTGNnY-amide (7), an NS3–NS5 hybrid, displaying a kcat/Km of approx. 20 M−1·s−1. Contrary to our expectations, the substrate representing the monobasic cleavage site sequence of the NS2B protein, Abz-KKQR-AGVLnY-amide (25), incorporating a glutamine residue at the P2 position, was comparatively well hydrolysed by the NS3 protease. The highest kcat value (5.8 min−1) of all peptides was found for the NS2B–capsid hybrid, Abz-KKQR-SAGMnY-amide (29). Ranking the native polyprotein cleavage site substrates according to their catalytic efficiencies would give the order capsid⋙NS2B/NS3>NS2A/NS2B> NS3/NS4A > NS4B/NS5, whereby cleavage of the capsid protein site is approx. 32-fold more efficient than cleavage of the second-best site, NS2B/NS3.

Figure 4. Kinetic constants for chimaeric peptide substrates based on native dengue polyprotein cleavage sites.

Combinations of prime and non-prime sequences for all five polyprotein junctions were synthesized and assayed for activity with the NS3 protease. Non-prime side sequences are indicated on the left-hand side and the influence of the corresponding prime side sequences is shown by the shaded bars as marked in the insets. Km values for sample peptides based on the capsid protein non-prime sequence are shown on an expanded scale in the inset. Abz group at the N-terminus and 3-nitrotyrosineamide residue at the C-terminus are included in all molecules.

None of the native cleavage site sequences produced the highest efficiency within their group of peptides and in three out of five groups of chimaeric peptides, the substrates containing the capsid protein prime side sequence SAGM appeared to be most efficiently hydrolysed by the NS3 protease.

Prime side preferences

To investigate the contribution of prime side residues to catalytic efficiency, we have used the modified native capsid protein cleavage sequence Abz-RRRR-SAGMnY-amide (36) as template to analyse the effects of truncations as well as of alanine replacements at the P1′ to P4′ positions (i.e. peptides 36–45). Kinetic data for this group of substrates are shown in Figure 5. Removal of the methionine residue at P4′ resulted in the most efficiently cleaved peptide, Abz-RRRR-SAGnY-amide (40), with a kcat/Km of 11087 M−1·s−1 (Figure 2). Further deletions at the prime side yielded peptides with significantly decreased binding affinities and rate constants. For the peptide Abz-RRRR-SnY-amide (42), kcat/Km is almost 10-fold lower when compared with Abz-RRRR-SAGnY-amide (40). These results are in agreement with the results of the substrate length mapping, which had indicated a strong preference of the NS3 protease for three residues in the prime side region. In addition to peptides mimicking native polyprotein cleavage sites, we have also included the tetrabasic sequence Abz-RRRR-nY-amide (45) in the assay and observed marginal activity at a kcat/Km of 112 M−1·s−1. Consistent with the observation by Li et al. [28] that an arginine residue at P1′ is accepted by the dengue virus serotype 2 protease albeit with very low activity (<10% when compared with serine), cleavage may have occurred within this tetrabasic sequence between the residues located at the P2 and P1 or P3 and P2 positions. Analysis of the Abz-RRRR-nY-amide (45) cleavage products by MS revealed that several alternative cleavage products, namely RR-nY-amide, Abz-RRR, Abz-RR, RR and R, were formed in trace amounts upon prolonged incubation (15 h, starting substrate completely consumed) with NS2B(H)–NS3pro. However, these side products could not be detected under conditions used for the determination of kinetic parameters (incubation time 10 min). In this case, only the expected cleavage products Abz-RRRR and nY-amide were observed on MS analysis, confirming that the dengue virus protease cleaves this substrate almost exclusively at the Arg–Tyr bond.

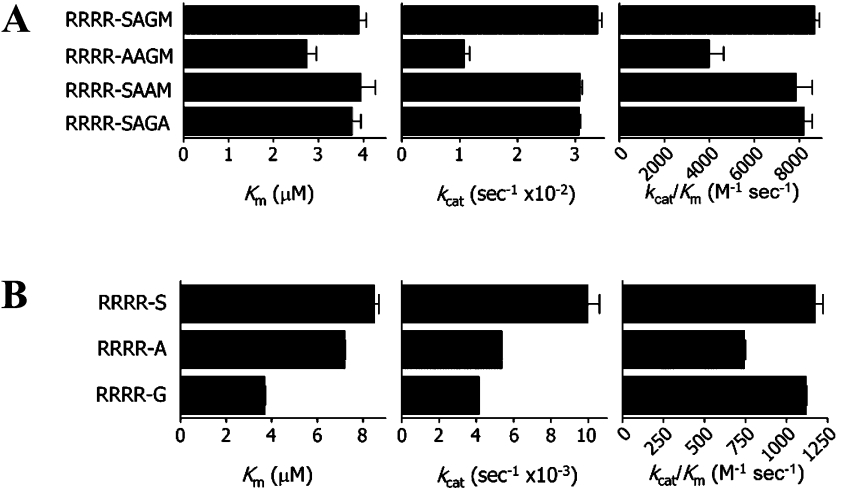

Figure 5. Kinetic constants for the cleavage of peptides by dengue NS3 protease.

(A) Alanine scanning in the prime side region. (B) Peptides with truncated prime side sequences. Amino acid sequences shown represent the central part of the substrate molecule (i.e., the Abz group at the N-terminus and 3-nitrotyrosineamide residue at the C-terminus included in all molecules are not shown). For each sample peptide, Km, kcat and the specificity constant kcat/Km are shown.

To further explore the relationships among residues in the prime side region, we have synthesized alanine-replacement peptides (37–39) at the P1′ through P4′ positions by using the peptide Abz-RRRR-SAGMnY-amide (36) as a template (Figure 5). A marked reduction (∼2-fold) in catalytic efficiency was found only for the substitution of serine at P1′, whereas kcat/Km values for alanine replacements at the P3′ and P4′ positions were comparable, thereby supporting the notion that the contribution of residues beyond the P4′ position to catalysis becomes negligible. Small unbranched amino acid residues are present in the native polyprotein cleavage sites at the P1′ position and the RRRR-X peptides (X=Ser, Ala or Gly) with optimized binding in the non-prime side region and were used to analyse preferences for the P1′ residue. Activities observed with serine and glycine at the P1′ positions were almost identical, whereas alanine at P1′ resulted in approx. 40% lower catalytic efficiency. Taken together, our results for determinants of cleavage efficiency by the dengue virus NS3 serine protease would suggest an optimal sequence length ranging from P4 to P3′, the presence of basic residues such as arginine at the P4 to P1 positions and small chain residues such as serine, glycine and alanine at the P1′ position with serine and glycine being preferred to alanine.

DISCUSSION

In general, virus-encoded proteases display an unusual degree of selectivity for their natural polyprotein substrates and only very few cases are known where the viral enzyme reacts with protein substrates derived from the host cell [31,32]. As for most proteases, the stringent specificity of the dengue virus NS3 protease for the native viral polyprotein precursor is defined by subsite interactions of the enzyme with its natural substrate. In the case of serine proteases within the chymotrypsin-fold family, these interactions are structurally conserved and in most known cases commonly reside within the P4–P3′ subsites in the vicinity of the catalytic triad [33–36]. Surprisingly, the crystal structure of the dengue virus NS3pro enzyme and the structure of the protease in complex with Bowman–Birk inhibitor revealed only a relatively shallow substrate-binding pocket with enzyme–substrate interactions that are confined to the P2 to P2′ region [24,37].

The precise mechanism by which the NS2B cofactor activates the NS3 protease is not elucidated in detail. However, recently published work offers some explanations for the cofactor-dependent activation [20,38]. Based on kinetic experiments using NS2B(H)–NS3pro and unliganded NS3pro, Yusof et al. [38] have suggested that additional interactions required for substrate binding are formed by a conformational rearrangement in the presence of NS2B. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments had identified individual residues within NS2B that are critical for the structural activation of the protease. A preponderant effect on catalytic-centre activity rather than Km values was found for substitutions within the NS2B activation domain, pointing to a role for the cofactor in the catalytic mechanism of the NS3 protease [20]. Competitive inhibition of the NS3 protease by product peptides derived from the prime side region of the polyprotein junctions has provided further evidence to suggest the existence of a substrate-binding site which is expanded in the NS2B(H)–NS3pro co-complex [27,29].

In the present study, we have revisited determinants of specificity and substrate recognition of the dengue virus serotype 2 NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease complex by using intramolecularly quenched fluorogenic substrates derived from native cleavage site sequences of the viral polyprotein. To investigate the structural reasons for substrate selectivity, we have generated frames of peptides with systematic variations in the sequences. In particular, we have addressed the following questions: (i) what is the preferred size for the NS3 protease substrates, (ii) what are the major determinants of substrate recognition in the non-prime region and (iii) what are the preferred substrate residues in the prime side region?

First, our experiments using peptide frames with systematic truncations at the non-prime and prime subsites have identified a substrate size ranging from P4 to P3′ which yields an optimal activity of the NS3 protease. Previously reported data had demonstrated that non-prime side interactions beyond P2 strongly contribute to substrate binding [27,29,38]. We have observed marked effects for arginine replacements at the P3 and P4 positions, supporting the notion that the presence of clustered basic residues in the non-prime region is a major determinant for substrate recognition of the dengue virus NS3 protease. This result would be in agreement with substrate profiling data previously reported by Li et al. [28] in so far as the preferred residue at P3 was identified as lysine followed by arginine. The preferred residue at P4, however, was identified as norleucine, followed by leucine, lysine and arginine at comparable activities, thus suggesting that basic and aliphatic residues are equally well tolerated at this position [28]. With our substrates the introduction of an arginine residue at P3 results in an increase in kcat/Km by almost 4-fold, and introduction of arginine residues at P3 and P4 in the capsid-protein-derived tetrabasic sequence RRRR results in a 30-fold increase of kcat/Km. The dramatic increase in enzymatic activity observed for the heptamer RRRR-SAG would imply an enormous degree of selectivity of the NS3 protease for the capsid protein over substrate sequences located within the non-structural region of the polyprotein. All four cleavage junctions in the non-structural region of the dengue virus polyprotein consist of sequences that are suboptimal for activity with the NS3 protease. Moreover, the activity data that we have obtained by using chimaeric peptides representing combinations of prime and non-prime side sequences of the polyprotein junctions show that nature has failed to produce the most efficient substrate sequence. It is tempting to speculate that the presence of cleavage sites with restricted reactivity limits the efficiency of processing in the non-structural region of the polyprotein, whereas large amounts of capsid protein required for virus assembly are generated by maximizing cleavage rates at this site. However, the precise mechanisms that are involved in the regulation of polyprotein processing are not elucidated in detail. It is conceivable that factors such as cellular localization to the membranes of the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) and protein–protein interactions with components of the viral replication machinery, such as the NS5 replicase, will affect the order of cleavages within the polyprotein substrate [39,40].

The presence of basic residues at the P3 and P4 positions drastically enhances reactivity of substrate peptides with the NS3 protease. Moreover, the results presented here demonstrate that the cleavage site sequence of the capsid protein is also optimized in the prime side region, where the sequence SAG consisting of three small or polar residues is found at the P1′–P3′ positions. Although the presence of dibasic residues at the P1 and P2 positions is probably the major determinant of substrate recognition for the flaviviral NS3 proteases, several studies of chymotrypsin-like fold serine proteases have suggested a significant role for prime site residues in substrate binding and catalysis [33,36,41,42]. Our results obtained for sequence variations at the prime side indicate a preference for small side-chain amino acids (serine, glycine and alanine) at the P1′ position with serine and glycine being preferred to alanine. The order of P1′ preferences resembles the findings of Li et al. [28], who demonstrated that dengue virus type 2 NS3 protease has a significant degree of selectivity for serine in P1′, followed by glycine and alanine. Their work has also shown an even higher degree of selectivity for serine at the P3′ position, whereas selection of residues at the P2′ and especially at the P4′ position seems to be relatively unrestrained.

Kinetic analysis of proteolytic processing events has pointed to the existence of a temporal hierarchy of cleavage events during polyprotein maturation and it was shown that an intramolecular cleavage reaction between NS2A and NS2B precedes cis cleavage at the NS2B/NS3 site [3]. However, a preferred order of processing events in the non-structural region of dengue virus has not been established conclusively to date. An unexpected result of our investigation is the high efficiency of cleavage observed with the native substrate sequence KKQRAGVL of the NS2B/NS3 polyprotein junction. This seems to formally contradict results previously reported in a number of studies, which have shown that cleavage activity with this ‘non-canonical’ substrate is relatively low when compared with the remaining polyprotein sites [25–28]. Li et al. [28] have shown by positional scanning of synthetic combinatorial libraries that the presence of glutamine in the P2 position yields only 35% of the reactivity when compared with arginine. However, with the exception of the report by Khumthong et al. [25] who have used dansylated dodecamer derivatives of the cleavage site peptides as substrates, previous studies by Leung et al. [27] and Li et al. [28] have employed substrates based on non-prime side sequences labelled with a p-nitroanilide residue at the P1′ position. It is interesting to note that all reported kcat values for substrates based on the NS2B/NS3 cleavage site are higher than those for substrates derived from the remaining junctions. However, Michaelis–Menten constants for these substrates reflect relatively inefficient cleavage resulting also in poor kcat/Km values [27,28]. The Km for the reaction of our substrate, Abz-KKQR-AGVLnY-amide (25), with the NS2B(H)–NS3pro protease was determined to be 89 μM, whereas previous studies have reported Km values of 984 μM [27] and 380 μM [28] for cleavage of the substrate peptide Ac-EVKKQR-pNA by the protease CF40-gly-NS3pro185. These apparently conflicting results can be explained if one assumes that the presence of the p-nitroanilide residue at the P1′ position is suboptimal and leads to inefficient binding, whereas the presence of prime side residues in the Abz-KKQRAGVLnY-amide (25) could account for a substantial decrease in Km and therefore stronger interaction with the NS3 protease. Moreover, the presence of residues at the P5 and P6 positions of the Ac-EVKKQR-pNA substrate may not inevitably lead to better binding as we have shown in the present paper by comparison of the peptide substrates in the FAAGRK and AGRK frames. Therefore these factors could likely contribute to grossly overestimated Km values for the NS2B/NS3 substrate sequence. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the NS2B(H)–NS3pro and the CF40-gly-NS3pro185 constructs of the dengue virus protease exhibit different rates of activity with a given substrate. Although this possibility seems to be rather unlikely at present, the question of differences in specificity between the two forms of the NS3 protease has to await the results of experiments using identical substrates for the two NS3 constructs under comparable conditions.

The results presented here corroborate earlier predictions for the substrate specificity of the NS3 protease which were based on product inhibition of the enzyme by peptides representing polyprotein cleavage junctions [29]. Competition assays with N-terminal cleavage products had shown that the presence of basic residues at the P3 and P4 positions of the product peptide resulted in increased inhibition of the NS3 protease in the low micromolar range.

Taken together, the data that are available now for the substrate specificity of the dengue virus NS3 protease support the view that this enzyme has developed an exceedingly stringent substrate specificity, which substantially limits the number of cleavable amino acid sequences and makes the cleavage junctions of the natural polyprotein precursor the preferred substrates. Together with the compartmentalization of the protease at the membranes of the ER, this observation would provide an explanation for the efficient discrimination of potential cellular substrates by the NS3 protease. Moreover, reaction of the NS3 protease with the natural polyprotein substrate sites seems to be modulated over a dynamic range of activities. The presence of cleavage sites with distinct reactivities is likely to be involved in the controlled processing of the precursor and maturation of the virus. The occupancy rules for subsites that were uncovered in specificity studies conducted so far offer the prospect to develop potent inhibitors against the dengue virus NS3 protease which exploit the unusual specificity characteristics of this important drug target and minimize interference with pharmacologically relevant proteases of the host cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Chanan Angsuthanasombat and Albert Ketterman (Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Mahidol University) for helpful suggestions, Dr Chartchai Krittanai (Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Mahidol University) for support and encouragement, and Anchanee Nirachanon for excellent secretarial assistance. This work was supported by a collaborative research grant from the SIDA (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) to J.E.S.W. and G.K.; the Swedish Research Council grant 621-2002-4711 (to J.E.S.W.); and Basic Science grant BRG4680006 (to G.K.) from the TRF (Thailand Research Fund). A Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. research scholarship from the TRF to P.N. is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Falgout B., Pethel M., Zhang Y. M., Lai C. J. Both nonstructural proteins NS2B and NS3 are required for the proteolytic processing of dengue virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 1991;65:2467–2475. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2467-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers T. J., Weir R. C., Grakoui A., McCourt D. W., Bazan J. F., Fletterick R. J., Rice C. M. Evidence that the N-terminal domain of nonstructural protein NS3 from yellow fever virus is a serine protease responsible for site-specific cleavages in the viral polyprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:8898–8902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preugschat F., Yao C. W., Strauss J. H. In vitro processing of dengue virus type 2 nonstructural proteins NS2A, NS2B, and NS3. J. Virol. 1990;64:4364–4374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4364-4374.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preugschat F., Strauss J. H. Processing of nonstructural proteins NS4A and NS4B of dengue 2 virus in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 1991;185:689–697. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90540-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias C. F., Preugschat F., Strauss J. H. Dengue 2 virus NS2B and NS3 form a stable complex that can cleave NS3 within the helicase domain. Virology. 1993;193:888–899. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin C., Amberg S. M., Chambers T. J., Rice C. M. Cleavage at a novel site in the NS4A region by the yellow fever virus NS2B-3 proteinase is a prerequisite for processing at the downstream 4A/4B signalase site. J. Virol. 1993;67:2327–2335. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2327-2335.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobigs M. Flavivirus premembrane protein cleavage and spike heterodimer secretion require the function of the viral proteinase NS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:6218–6222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo K. F., Wright P. J. Internal proteolysis of the NS3 protein specified by dengue virus 2. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:337–341. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-2-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi E., Pessi A. Inhibiting viral proteases: challenges and opportunities. Biopolymers. 2002;66:101–114. doi: 10.1002/bip.10230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pessi A. A personal account of the role of peptide research in drug discovery: the case of hepatitis C. J. Pept. Sci. 2001;7:2–14. doi: 10.1002/psc.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan M. D., Monaghan S., Flint M. Virus-encoded proteinases of the Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 1998;79:947–959. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H., Clum S., You S., Ebner K. E., Padmanabhan R. The serine protease and RNA-stimulated nucleoside triphosphatase and RNA helicase functional domains of dengue virus type 2 NS3 converge within a region of 20 amino acids. J. Virol. 1999;73:3108–3116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3108-3116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorbalenya A. E., Donchenko A. P., Koonin E. V., Blinov V. M. N-terminal domains of putative helicases of flavi- and pestiviruses may be serine proteases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3889–3897. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.10.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadare G., Haenni A. L. Virus-encoded RNA helicases. J. Virol. 1997;71:2583–2590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2583-2590.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartelma G., Padmanabhan R. Expression, purification, and characterization of the RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity of dengue virus type 2 nonstructural protein 3. Virology. 2002;299:122–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers T. J., Grakoui A., Rice C. M. Processing of the yellow fever virus nonstructural polyprotein: a catalytically active NS3 proteinase domain and NS2B are required for cleavages at dibasic sites. J. Virol. 1991;65:6042–6050. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6042-6050.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wengler G., Czaya G., Farber P. M., Hegemann J. H. In vitro synthesis of West Nile virus proteins indicates that the amino-terminal segment of the NS3 protein contains the active centre of the protease which cleaves the viral polyprotein after multiple basic amino acids. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:851–858. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-4-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L., Mohan P. M., Padmanabhan R. Processing and localization of dengue virus type 2 polyprotein precursor NS3-NS4A-NS4B-NS5. J. Virol. 1992;66:7549–7554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7549-7554.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falgout B., Miller R. H., Lai C. J. Deletion analysis of dengue virus type 4 nonstructural protein NS2B: identification of a domain required for NS2B-NS3 protease activity. J. Virol. 1993;67:2034–2042. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2034-2042.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niyomrattanakit P., Winoyanuwattikun P., Chanprapaph S., Angsuthanasombat C., Panyim S., Katzenmeier G. Identification of residues in the dengue virus type 2 NS2B cofactor that are critical for NS3 protease activation. J. Virol. 2004;78:13708–13716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13708-13716.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbato G., Cicero D. O., Nardi M. C., Steinkuhler C., Cortese R., De Francesco R., Bazzo R. The solution structure of the N-terminal proteinase domain of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protein provides new insights into its activation and catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:371–384. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J. L., Morgenstern K. A., Lin C., Fox T., Dwyer M. D., Landro J. A., Chambers S. P., Markland W., Lepre C. A., O'Malley E. T., et al. Crystal structure of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease domain complexed with a synthetic NS4A cofactor peptide. Cell. 1996;87:343–355. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clum S., Ebner K. E., Padmanabhan R. Cotranslational membrane insertion of the serine proteinase precursor NS2B-NS3(Pro) of dengue virus type 2 is required for efficient in vitro processing and is mediated through the hydrophobic regions of NS2B. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30715–30723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murthy H. M., Clum S., Padmanabhan R. Dengue virus NS3 serine protease. Crystal structure and insights into interaction of the active site with substrates by molecular modeling and structural analysis of mutational effects. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5573–5580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khumthong R., Angsuthanasombat C., Panyim S., Katzenmeier G. In vitro determination of dengue virus type 2 NS2B-NS3 protease activity with fluorescent peptide substrates. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;35:206–212. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khumthong R., Niyomrattanakit P., Chanprapaph S., Angsuthanasombat C., Panyim S., Katzenmeier G. Steady-state cleavage kinetics for dengue virus type 2 NS2B-NS3(pro) serine protease with synthetic peptides. Protein Pept. Lett. 2003;10:19–26. doi: 10.2174/0929866033408228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung D., Schroder K., White H., Fang N. X., Stoermer M. J., Abbenante G., Martin J. L., Young P. R., Fairlie D. P. Activity of recombinant dengue 2 virus NS3 protease in the presence of a truncated NS2B co-factor, small peptide substrates, and inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:45762–45771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J., Lim S. P., Beer D., Patel V., Wen D., Tumanut C., Tully D. C., Williams J. A., Jiricek J., Priestle J. P., et al. Functional profiling of recombinant NS3 proteases from all four serotypes of dengue virus using tetra- and octa-peptide substrate libraries. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28766–28774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chanprapaph S., Saparpakorn P., Sangma C., Niyomrattanakit P., Hannongbua S., Angsuthanasombat C., Katzenmeier G. Competitive inhibition of the dengue virus NS3 serine protease by synthetic peptides representing polyprotein cleavage sites. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;330:1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Kati W., Chen C. M., Tripathi R., Molla A., Kohlbrenner W. Use of a fluorescence plate reader for measuring kinetic parameters with inner filter effect correction. Anal. Biochem. 1999;267:331–335. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuyumcu-Martinez N. M., Joachims M., Lloyd R. E. Efficient cleavage of ribosome-associated poly(A)-binding protein by enterovirus 3C protease. J. Virol. 2002;76:2062–2074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2062-2074.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser W., Cencic R., Skern T. Foot-and-mouth disease virus leader proteinase: involvement of C-terminal residues in self-processing and cleavage of eIF4GI. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35473–35481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coombs G. S., Rao M. S., Olson A. J., Dawson P. E., Madison E. L. Revisiting catalysis by chymotrypsin family serine proteases using peptide substrates and inhibitors with unnatural main chains. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24074–24079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krem M. M., Rose T., Di Cera E. The C-terminal sequence encodes function in serine proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28063–28066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perona J. J., Craik C. S. Evolutionary divergence of substrate specificity within the chymotrypsin-like serine protease fold. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:29987–29990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.29987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schellenberger V., Turck C. W., Rutter W. J. Role of the S′ subsites in serine protease catalysis. Active-site mapping of rat chymotrypsin, rat trypsin, alpha-lytic protease, and cercarial protease from Schistosoma mansoni. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4251–4257. doi: 10.1021/bi00180a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murthy H. M., Judge K., DeLucas L., Padmanabhan R. Crystal structure of Dengue virus NS3 protease in complex with a Bowman-Birk inhibitor: implications for flaviviral polyprotein processing and drug design. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:759–767. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusof R., Clum S., Wetzel M., Murthy H. M., Padmanabhan R. Purified NS2B/NS3 serine protease of dengue virus type 2 exhibits cofactor NS2B dependence for cleavage of substrates with dibasic amino acids in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9963–9969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks A. J., Johansson M., John A. V., Xu Y., Jans D. A., Vasudevan S. G. The interdomain region of dengue NS5 protein that binds to the viral helicase NS3 contains independently functional importin beta 1 and importin alpha/beta-recognized nuclear localization signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:36399–36407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yon C., Teramoto T., Mueller N., Phelan J., Ganesh V. K., Murthy K. H., Padmanabhan R. Modulation of the nucleoside triphosphatase/RNA helicase and 5′-RNA triphosphatase activities of dengue virus type 2 nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) by interaction with NS5, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27412–27419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waugh S. M., Harris J. L., Fletterick R., Craik C. S. The structure of the pro-apoptotic protease granzyme B reveals the molecular determinants of its specificity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:762–765. doi: 10.1038/78992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye S., Cech A. L., Belmares R., Bergstrom R. C., Tong Y., Corey D. R., Kanost M. R., Goldsmith E. J. The structure of a Michaelis serpin–protease complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:979–983. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]