Abstract

We have previously shown that cultured LHRH-1 neurons, derived from monkey olfactory placode region, exhibit pulsatile LHRH-1 release at hourly intervals and spontaneous intracellular calcium, [Ca2+]i, oscillations, which synchronize at a frequency similar to LHRH-1 release. Brief application of estrogen induced a rapid increase in the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations and the frequency of synchronizations. The estrogen-induced frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations was mediated by estrogen receptors (ER), whereas the frequency of synchronizations was not mediated by ER. In the present study we further examined the rapid action of estrogen using patch-clamp recording in primate LHRH-1 neurons. Cell-attached patch-clamp recording showed that LHRH-1 neurons exhibited monophasic or biphasic action currents, which were sensitive to an increase in extracellular K+ and the sodium channel blocker, TTX. The majority (90%) of LHRH-1 neurons showed irregular firing patterns comprised of bursts and irregular beatings of action currents, which further formed a ‘cluster’ firing pattern. Brief application of 17β-estradiol (E2, 1 nM) increased the firing frequency and burst duration of LHRH-1 neurons with a latency of 60–120 s for up to 25 min. ICI182,780, an ER antagonist blocked the E2-induced increase in the firing activity of LHRH-1 neurons. These results suggest that 1) primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibit complex firing patterns comprised of activities with different time domains, 2) estrogen causes rapid stimulatory action of firing activity, and 3) this estrogen action is mediated by ER in primate LHRH-1 neurons.

Keywords: firing pattern, bursts, estrogen effects, LHRH-1 neurons, primates

Introduction

Pulsatile release of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH)-1 is crucial in control of reproductive function. An episodic increase in multiple unit activity recorded from the medial basal hypothalamus correlates with pulsatile LH release (1–3) and this episodic multiple unit activity has been proposed to reflect activity of LHRH-1 neurons. In vitro calcium imaging studies indicate that LHRH-1 neurons appear to possess an intrinsic pulse-generating mechanism (4, 5) because LHRH-1 neurons exhibit spontaneous intracellular calcium, [Ca2+]i, oscillations, which synchronize at a frequency similar to LHRH-1 release (6–8). Nonetheless, the electrophysiological properties of LHRH-1 neurons responsible for pulsatile LHRH-1 release remain elusive.

Studies elucidating the physiological properties of LHRH-1 neurons in vivo using electrophysiological approaches are difficult because of their diffuse distribution pattern and paucity in number in the hypothalamus-preoptic area (9). To overcome this obstruction, LHRH-1 neurons in mice and rats were genetically labeled by promoter-driven transgenic manipulation, so that LHRH-1 neurons can be visualized for identification prior to electrical recording. In fact, this approach has been highly successful in mice and rats (10–20). However, LHRH-1 neurons labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in non-human primates are not yet available.

We have previously established a primary cell culture system for LHRH-1 neurons derived from the olfactory placode region of the rhesus monkey at embryonic age 35–37 (E35–E37) (21) and have shown that this culture system is useful for cellular and molecular studies. In the present study, we recorded activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons using the cell-attached patch-clamp method. First, we determined firing patterns of electrical activity and second, we examined whether estrogen rapidly alters the electrical activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons. The results suggest that 1) primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibit complex firing patterns comprised of activities with different time domains, and 2) estrogen causes rapid stimulatory action in the firing activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons via an ICI182,780-sensitive pathway.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue culture

Rhesus monkey embryos (Macaca mulatta) from time-mated pregnant females were delivered by cesarean section under isoflurane anesthesia. A total of 5 embryos at embryonic day (E) 35 to E37 were used in this study. The sexes of embryos were not determined, as the gonads were not yet differentiated at this stage of development. All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the standards outlined in “Principles for Use of Animals and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” The protocol used in the studies was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin.

The methods for culture of LHRH-1 neurons derived from embryonic tissue have been described in detail elsewhere (6, 7, 21). Briefly, the olfactory placode region and ventral LHRH-1 neuron migratory pathway (terminal nerve region) were dissected out, cut into small (< 1 mm3) pieces, and plated on glass coverslips (n = 24–32 individual coverslips per embryo). Cultures were grown in a growth medium (Medium 199, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with L-glutamine (Sigma), 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 0.6% glucose, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma) under 1.5% CO2 and 98.5% air at 37 C for at least 2 weeks before experiments. Because of concerns regarding unknown effects of serum, half of the cultures from each embryo were grown in a modified growth medium (based on DMEM/F-12, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), which contains 2% B27serum free supplement (50x, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), L-glutamine (Sigma), and gentamicin (Sigma), but neither serum nor phenol red. The medium was replaced every 1–3 days. Recording experiments were conducted in cells cultured for 3–5 weeks. A total of 62 cultures (10–15 cultures from each embryo) were used for examination of the firing pattern (22 cultures), the effects of high K+ and TTX (6 cultures), and the effects of estrogen (34 cultures). In all experiments, approximately half of the cultures were grown in serum free medium.

Materials

For treatment of cultured LHRH-1 neurons, 17β-estradiol (E2) was purchased from Schering Corporation (Bloomfield, NJ). The pure antagonist for ER, ICI182,780 (ICI), was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). The voltage dependent sodium channel blocker, tetrodotoxin (TTX), was purchased from Sigma. Electrophysiological recording and data analysis

We recorded action currents generated by action potentials from primary LHRH-1 neurons in the cell-attached patch configuration of patch-clamp technique using a PC-501A patch-clamp amplifier (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). During recordings, cultures were continuously perfused with oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; in mM: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose, pH 7.4 with NaOH) at a flow rate of 200–300 μl/min at room temperature (22–25 C). Cells were observed with a Nikon TE-300 inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with differential interference contrast optics. Recording electrode (3–6 megaohms) was made from borosilicate capillary glass (type 8520, OD/ID 1.5/1.16 mm, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) using a Flaming/Brown Micropipette Puller (model P-87, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Patch pipettes were filled with aCSF and were targeted to LHRH-1 neurons (see below) using an NMN-21 three-dimensional mechanical micromanipulator (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Slight positive pressure was applied to the pipette before entering bath and maintained until attaching to the LHRH-1 neuron. Subsequently, gentle negative pressure was applied to the pipette to achieve the cell-attached patch configuration (seal resistances were ≥ 1 gigaohm, except for one case was 0.3 gigaohms). The firing activity recording was done in voltage-clamp mode with a holding potential of 0 mV, filtering at 2 kHz. The recording was continued for up to 45 min and digitized by a combination of Digidata1322A data acquisition interface and pClamp9 data acquisition & analysis software package (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA).

The effects of TTX (0.5 μM) were examined by direct application of the drug to the bath for 2 min. The effects of E2 (1 nM) were similarly examined by infusion for 10 min. Prior to E2 application, firing activity was recorded at least 10 min and recording was continued for at least 10 min after E2. The blockage of the E2-induced firing activity was examined by the following protocol. After the recording of the basal firing rate for at least 10 min, ICI (0.1 μM) infusion was started 10 min before the 10-min infusion of E2 or vehicle. ICI infusion was continued at least 10 min after E2.

Individual spikes and bursts of action currents were detected using Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). To identify clusters (slower time-course changes) of increased electrical activity within each cell-attached recording, we used the Cluster7 computer algorithm (22). Cluster7 compares clusters of points by pooled t-test to look for peaks and nadirs over time. For this analysis, we detected timing of action currents and binned the number of action currents at 10-s intervals as a data-set for Cluster7. Using 6- point (=1 min) settings of peak and nadir periods each, Cluster7 identified the location of clusters, that were comprised of both multiple bursts in rapid succession and irregular beatings of action currents, and calculated the durations and intervals for recordings with multiple identified clusters. Cluster7 sometimes missed clusters of firing very near the beginning or end of the data series, as it requires a string of data flanking a peak for positive identification. Therefore, for cluster analysis we chose recordings that have a sufficient duration, at least 20 min (n=19 for basic firing pattern examination, n=9 for E2, n=7 for vehicle control). Moreover, during the course of analysis we noticed that a cluster was comprised of periodical bursting of action currents. We defined a ‘burst’, as the events comprising at least three consecutive action currents that occur at intervals less than 500 ms.

Identification of LHRH-1 neurons and Immunocytochemistry

Our cultures contain numerous epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and other types of unidentified cells in addition to primary LHRH-1 neurons. However, LHRH-1 neurons were easily identifiable during patch-clamp recording based on their morphology, such as ovoid in shape and large soma (≥12 μm in size) with neurites forming neuronal bundles, and their migratory pattern. To identify LHRH-1 neurons, we used the procedure detailed previously (6, 23). Briefly, we took a photomicrograph of a tested LHRH-1 neuron and recorded a reference grid number on the coverslip after the completion of each patch-clamp recording to facilitate locating the cells after immunostaining. After the completion of recording, cultures were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for immunocytochemistry.

LHRH-1 neurons were identified using standard immunocytochemical procedures with the antisera cocktail GF-6 and LR-1 (gifts from Dr. N. M. Sherwood. University of British Victoria, Victoria, Canada; 1:9,000 dilution and Dr. R. A. Benoit, University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada; 1:15,000, respectively), VECTASTAIN ABC peroxydase system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the chromagen, as described previously (6, 23). After staining, tested LHRH-1-immunopositive neurons were matched to the photomicrographic images. LHRH-1 immunonegative neurons in cultures were rare, but were excluded from analysis when they were found.

Statistical analysis

The results from cells grown in medium with or without serum were combined for statistical analysis, as they were not different. For quantitative analysis of the estrogen effects on the firing activity, we obtained the frequency during 10-min periods before and after the initiation of the E2 treatment. Because there were considerable variations in the firing frequency among individual neurons, before statistical analysis we normalized the data with following equation.

The effects of E2 and ICI (between-group comparisons) on the firing pattern of LHRH-1 neurons were examined using one-tailed alternate Welch t-test. All data are presented as means ± SEM. Significance was attained at p<0.05.

Results

Cell-attached patch recordings revealed firing activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons

Using the patch-clamp technique with the cell-attached patch configuration we observed cultured LHRH-1 neurons derived from the olfactory placode region of rhesus monkeys exhibiting spontaneous action potentials. In this configuration, action potentials can be recorded as capacitative currents (= action currents), reflecting the unclamped action potential arising from intact cells without alteration of intracellular constituents. As seen in examples of action currents (Fig. 1A) recorded from two LHRH-1 neurons, the action currents exhibited either monophasic (Fig. 1Aa) or biphasic (Fig. 1Ab) profiles. To confirm whether these currents reflect the action potentials of LHRH-1 neurons, the effects of the sodium channel blocker TTX were examined. Bath application of TTX (0.5 μM; 2 min) blocked the generation of action currents (Fig. 1C) for approximately 10 min. This TTX effect was reversible, as spontaneous action currents returned by 10–11 min after TTX removal (n=3 in 3 cultures). Depolarization with an increase in extracellular K+ (15 or 30 mM) also evoked an increase in frequency of action currents (n= 3 in 3 cultures, Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Cell-attached recording revealed the firing pattern of primate LHRH-1 neurons in vitro. Action currents recorded from LHRH neurons exhibited either monophasic (Aa) or biphasic patterns (Ab). Bath application of 15 mM K+ for 2 min increased the frequency of action currents (B), whereas TTX (0.5 μM, 2 min) reversibly blocked generation of action currents (C).

Firing pattern of primate LHRH-1 neurons

Primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibited a random pattern of action currents, comprised of mixtures of rapid bursts and irregular beatings (Fig. 2A). This firing pattern was disrupted by short periods (<2 min) of quiescence, but there were no long quiescence periods (10–30 min), unlike reports in mice (12, 19, 24). The firing frequency of primate LHRH-1 neurons was normally between <0.001 and 10 Hz (mean = 2.7±0.1 Hz; calculated from 11300 events from 22 neurons), but the instantaneous firing frequency reached as high as 100 Hz. Detailed analysis indicated that the firing pattern was comprised of slower changes in firing activity, which was named a ‘cluster’ (Fig. 2B). A single ‘cluster’ was further comprised of multiple rapid ‘bursts’ (Fig. 2C) and irregular beatings of action currents. A single ‘burst’ was further comprised of multiple spikes of action currents (Fig. 2D). In the example shown in Fig. 2C, five action currents formed a burst.

Figure 2.

Primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibited a random pattern of action currents, which were comprised of a mixture of rapid bursts and irregular beatings (A). The firing pattern of these neurons (A) was composed of a complex rhythmic activity, which was comprised of ‘clusters’ (slower changes of firing activity, B) and rapid ‘bursts’ of action currents (C). B is an enlargement of the bracket in A, C is an enlargement of the bracket in B. Single spike is shown in (D).

Cluster: Slower changes in firing activity were detected by Cluster7 pulse detection algorithm (Fig. 3A). The mean duration of a ‘cluster’ was 161.4±8.1 s (ranging from 60 to 420 s; n=97 events from 19 neurons), which was separated by a 104.7±23.3 s mean interval (ranging from 10 to 1420 s; n=78 events from 19 neurons), i.e., clusters occurred at approximately 1–25 min intervals. Three of 22 neurons did not show any clusters. The frequency distribution histogram indicated that both duration (Fig. 3Ba) and interval (Fig. 3Bb) of clusters showed long-tailed distribution. The median values of the duration and interval of a cluster were 140 s and 60 s, respectively (Table 1A).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of cluster and burst activities. An example of detected ‘cluster’ activity from a primate LHRH-1 neuron using Cluster7 algorithm (A). Distribution patterns of the cluster duration (Ba) and cluster interval (Bb) from 97 events in 19 neurons are shown. The interval of clusters was variable, ranging from 10 to 1420 s. Burst firing pattern also showed considerable variability (C), i.e., the number of action currents per burst, burst durations, and burst intervals vary from neuron to neuron, as shown in (Ca) and (Cb). Some LHRH-1 neurons exhibited a stereotypical pattern of rhythmic bursts with short duration (Cc), in which the first action current with the highest amplitude was followed by multiple action currents with gradually decreasing amplitudes (inset in Cc). The distribution pattern of spikes per burst (Da), burst duration (Db), and inter-burst interval (Dc) is shown from 597 events in 20 neurons.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the firing pattern in LHRH neurons

| A: Cluster

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Interval | ||

| Mean ± SE | 161.4±8.1 s | 1 04.7 ± 23.3s | |

| Median | 140s | 60s | |

| Maximum | 420s | 1420s | |

| Minimum | 60s | 10s | |

| Number | 97 events from 19 neurons | 78 events from 19 neurons | |

| B: Burst

| |||

| Spikes number per burst | Duration | Interburst Interval | |

| Mean ± SE | 5.7 ±0.3 | 1. 1 04 ± 0.048s | 39.548 ±5.1 05s |

| Median | 4 | 0.790 s | 6.518s |

| Maximum | 72 | 15.950s | 1525.823s |

| Minimum | 3 | 0.025 s | 0.503 s |

| Number | 597 events from 20 neurons | 597 events from 20 neurons | 577 events from 20 neurons |

Burst: Based on the definition that at least three consecutive action currents occurred within a period of less than 500 ms, we found that 90% of LHRH-1 neurons (n=20/22) exhibited burst firing activity. Patterns of ‘bursts’ differed from neuron to neuron, i.e., the number of spikes per burst, burst duration, and burst interval were variable (Fig. 3C). For example, one LHRH-1 neuron showed bursts with a relatively low firing frequency and long duration (Fig. 3Ca), whereas another LHRH-1 neuron showed a high firing frequency and short duration (Fig. 3Cb). A small number of LHRH-1 neurons (n=2/20) exhibited a stereotype pattern of rhythmic bursts with two to seven spikes occurring at 5–90 s intervals with a duration less than 0.1 s (Fig. 3Cc). In these neurons, the amplitude of the first spike was highest and followed by spikes with amplitudes gradually decreasing (Fig. 3Cc, inset). The frequency and duration were also variable from event to event within a single neuron. Reflecting these variations, the distribution histograms for the spikes per burst (a), burst duration (b), and inter-burst interval (c) from 597 pooled burst events from 20 neurons, indicated that these parameters exhibit long-tailed distribution (Figs. 3D). The mean (±SEM) spikes per burst, burst duration, and interburst interval were 5.7±0.3 (ranging from 3 to 72; n=597 events from 20 neurons), 1.104±0.048 s (ranging from 0.025 to 15.95 s, n=597 events from 20 neurons) and 39.548±5.105 s (ranging from 0.53 to 1525.823 s; n=577 from 20 neurons), respectively (Table 1B). The median values were 4 for spike number, 0.79 s for burst duration and 6.518 s for interburst interval (Table 1B).

Effect of estrogen on the firing pattern of primate LHRH-1 neurons

To examine whether E2 alters firing activity of LHRH-1 neurons, we applied E2 (1 nM) in the bath for 10 min. This duration was chosen based on the observations that 2-min exposure of LHRH-1 neurons to TTX caused an expected response for ~10 min (see Fig. 1C) and the estrogen application for 10 min alters the pattern of intracellular calcium oscillations in our cultured LHRH-1 neurons. Prior to E2 application, LHRH-1 neurons exhibited a random firing pattern, which was comprised of a mixture of rapid bursts and irregular single spikes (Figs. 4Ba, 4Ca, 4Da, and 4Ea). E2 application resulted in an increase in the firing activity of LHRH-1 neurons (Figs. 4Ba, 4Cb, 4Da, and 4Eb). The time course of changes by E2 was clearly observed with an integrated plot of spike number per 10 s (Fig. 4Bb and 4Db). The latency of the estrogen induced frequency increase was 60~120 s. This E2-induced facilitation was continued as long as the seal integrity of the patch electrode was maintained (up to 25 min). Quantitative analysis suggested that E2 (1 nM) stimulated 7 of 9 (78%) LHRH-1 neurons. The magnitude of the firing frequency increase was 249.7±109.4 % (n=9 neurons) from the basal firing rate prior to E2, and this was significantly higher (P<0.05; Fig. 5A) than that in vehicle controls (9.3 ± 11.7 %; n = 7 neurons). In contrast, vehicle application for 10 min did not cause any significant changes in the firing pattern (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Effects of E2 on firing activity in primate LHRH-1 neurons. An example of vehicle (A) and 2 examples of the E2 effects (B, D) are shown. A: Bath application of vehicle for 10 min caused no significant effects on firing activity. B and D: Bath application of E2 (1 nM) for 10 min facilitated firing activity (Ba and Da). The time course of the E2- induced increase in firing activity is clearly seen in an integrated plot with the spike number per 10 s (Bb and Db). C and E: Detailed profiles of the E2 effects on action currents. Firing activities 10 min before (Ca and Ea) and during E2 application (Cb and Eb) from B and D, respectively, are shown. Further detailed profiles during a 1 min period “before” (Ca and Ea) and “during” E2 application (Cb and Eb), corresponding period indicated by dotted lines, are shown below. Note that the latency of the E2-induced facilitation of firing activity was 60–120 s and this effect lasted up to 25 min.

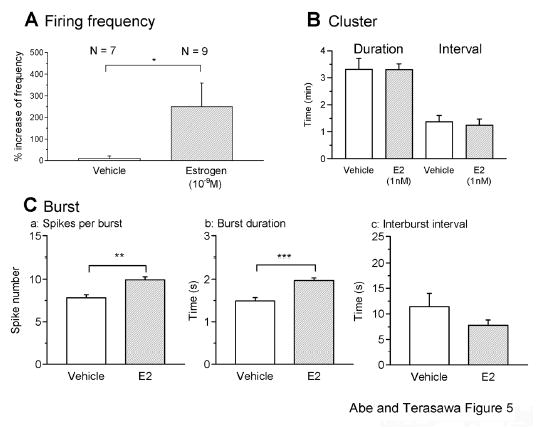

Figure 5.

The quantitative analysis of the effects of estrogen on firing activity in LHRH-1 neurons. Changes in the firing frequency (A), cluster (B), and burst activity (C) by vehicle and E2 (1 nM) are shown. A: The firing frequency (normalized value) was significantly increased by bath application of E2 (* P < 0.05, one-tailed alternate Welch t-test) when compared with vehicle controls. B: E2 application had no effect on cluster activity (P > 0.05). C: E2 significantly increased the spike number per burst (Ca, ** P < 0.01) and burst duration (Cb, *** P < 0.001), but not interburst interval (Cc, P > 0.05) in LHRH-1 neurons.

A comparison of the burst characteristics during the 10-min periods before and after the initiation of E2 infusion indicated that E2 significantly increased the spike number per burst (9.92±0.36 spikes in E2 vs. 7.82±0.38 spikes in vehicle; n=1949 events from 9 neurons and 474 events from 7 neurons, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 5Ca) and burst duration (1.97±0.06 s in E2 vs. 1.49±0.08 s in vehicle; P<0.001; Fig. 5Cb), but did not alter the interburst interval (7.79±1.05 s in E2 vs. 11.44±2.62 s in vehicle; P>0.05; Fig. 5Cc). In contrast, E2 did not induce significant changes in the cluster pattern: The duration (198.3±12.9 s in E2 vs. 198.8±24.9 s in vehicle, n=60 events from 9 neurons and 26 events from 7 neurons, respectively; P>0.05) and interval (74.5±13.9 s in E2 vs. 82.7±13.9 s in vehicle; P>0.05) of clusters (Fig. 5B) were not significantly different. These data suggested that E2 increased firing activity of LHRH-1 neurons by increasing firing frequency and burst duration, but not cluster pattern.

The effects of ICI on the estrogen-induced firing activity

To determine whether the E2-induced increase in firing activity is mediated by classical ER, we tested the effects of ICI, a pure antagonist for both ERα and ERβ. ICI was infused for 10 min prior to E2 and continued through the 10-min E2 application until the end of recording. ICI (0.1 μM) clearly blocked the E2-induced increase in the firing activity of LHRH-1 neurons (Fig. 6). Firing activity during the ICI (0.1 μM) + E2 (1nM) treatment (Fig. 6Bc) was not different from that during the ICI alone (0.1 μM, Fig. 6Bb) or the control period (Fig. 6Ba).

Figure 6.

An example of the effect of the estrogen receptor antagonist, ICI on the E2- induced facilitation of firing activity in LHRH-1 neurons. A: ICI (0.1 μM) was applied to bath starting 10 min before E2 and continued for the entire recording period. ICI blocked the facilitatory action of E2 on firing activity, as seen in a raw trace (Aa) and an integrated plot (Ab). B: Detailed profiles of the ICI effects on action currents. Firing activity in the control period (Ba), during ICI alone (Bb), and during E2 application with ICI (Bc) are shown. Further detailed profiles during the 1 min period, indicated by dotted lines, are also shown in the bottom panel. Note that there were no significant changes in firing activity during these periods.

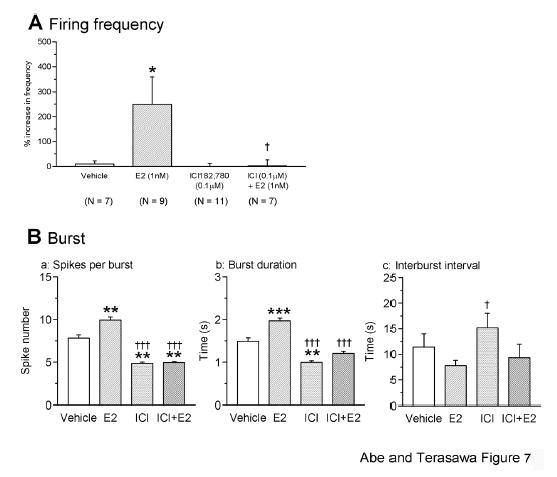

Quantitative analysis indicated that the firing frequency (Fig. 7A), spike number per burst (Fig. 7Ba), and burst duration (Fig. 7Bb) of the E2+ICI group were significantly lower than the E2 group (for all P<0.01). Moreover, there were no significant differences between the ICI and ICI+E2 group in all parameters examined: Firing frequency (2.49±23.7 % in ICI+E2 vs. −0.47±13.78 % in ICI alone; n= 7 and 11 neurons, respectively; P>0.05; Fig. 7A), spikes per burst (4.9±0.2 in ICI+E2, vs. 4.8±0.1 in ICI alone; n=478 events from 7 neurons and 377 events from 11 neurons; P>0.05; Fig. 7Ba), and burst duration (1.208±0.049 s in ICI+E2 vs. 0.997±0.034 s in ICI alone; P>0.05; Fig. 7Bb). Application of ICI alone did not induce significant changes in firing frequency (−0.47±13.78 % in ICI alone vs. 9.3 ± 11.7 % in vehicle; n= 11 and 7 neurons, respectively; P>0.05; Fig. 7A). Interestingly, ICI alone decreased the spikes per burst (4.8±0.1 in ICI alone vs. 7.82±0.38 in vehicle controls; n= 377 events from 11 neurons and 474 events from 7 neurons, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 7Ba) and burst duration (0.997±0.034 s in ICI alone vs. 1.49±0.08 s in vehicle controls, respectively; P<0.01; Fig. 7Bb) when compared to vehicle controls.

Fig. 7.

ICI blocks the estrogen-induced firing increase in LHRH-1 neurons. Changes in the firing frequency (A) and burst activity (B) by treatments with ICI (0.1 μM) alone or ICI + E2 (1 nM) are shown. ICI completely blocked the E2-induced increase in firing activity, as seen bath application of E2 under the presence of ICI did not increase the frequency (A), spike number per burst (Ba), or burst duration (Bb). The spike number per burst (Ba) and burst duration (Bb) in the ICI group were also lower than vehicle control. Interburst interval with ICI alone was significantly different from E2 (Bc). *: P<0.05 vs. vehicle; †: P<0.05 vs E2; **: P<0.01 vs. vehicle; : P<0.001 vs vehicle; †††: P<0.001 vs. E2.

Discussion

In the present study using cell-attached patch-clamp recording we found that 1) primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibited monophasic or biphasic action currents, which were sensitive to an increase in extracellular K+ and TTX, 2) primate LHRH-1 neurons showed irregular high frequency burst firing patterns, 3) multiple bursts and irregular beatings of action currents further formed a ‘cluster’ firing pattern, 4) infusion of E2 increased the number of firings, spikes per burst, and burst duration, and 5) the estrogen receptor antagonist, ICI, blocked the E2-induced increase in firing activity in primate LHRH-1 neurons.

We were successful in recording the firing activity of single LHRH-1 neurons in the rhesus monkey. To our knowledge, this is the first description on electrophysiological characteristics of primate LHRH-1 neurons. Because in the present study recording experiments were conducted at room temperature, some of our observations may not fully represent physiological conditions. The frequency (~3 Hz) of spontaneous activity in primate neurons is similar to that described in transgenic mouse LHRH-1 neurons (11, 12), and cultured LHRH-1 neurons from mouse olfactory placodes (25). Firing activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons was increased by depolarization with a high extracellular K+ and eliminated by TTX. Activation or suppression of neural activity by high K+ or TTX in LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells has been previously reported (12, 26, 27). Similarly, an increase in LHRH-1 release and [Ca2+]i oscillations induced by high K+, and a decrease in LHRH-1 release and [Ca2+]i oscillations induced by TTX in LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells have been extensively reported (6, 26, 28, 29). These reports together with the observations in this study suggest that membrane depolarization is essential for neurosecretion in LHRH-1 neurons.

Electrophysiological recording studies indicate that firing activity of GFP-labeled mouse LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells exhibit an episodic pattern separated by a 10–30 min quiescence period (13, 19, 30, 31). Moenter and colleagues (16, 19) further describe that mouse LHRH-1 neurons exhibit a firing pattern consisting of bursts (trains of multiple action currents) which occur at <20 s intervals, clusters (trains of multiple bursts) which occur at 6–8 min intervals, and episodes (trains of multiple clusters) which occur at 20–30 min. These authors categorize burst, cluster, and episodes, as high, intermediate, and low frequency rhythms, respectively, and suggest that episodic, not burst or cluster, firing rhythms may correspond to neurosecretion in mouse LHRH-1 neurons (16, 19). The pulse interval of LH release in mice, rats, and GT1 cells is ~30 min (29, 32–35). In the present study we found that primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibit a firing pattern consisting of bursts (40 s mean interburst interval with 1 s mean burst duration) and irregular single spikes, which further form cluster firing activity (trains of multiple bursts lasting 3–7 min, occurring at 1–25 min intervals). However, we did not observe a long quiescence of firing activity, or the episodic rhythm of firings with a longer time domain, described in mouse LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells. These characteristics in monkey LHRH-1 neurons differ from those in mouse LHRH neurons and GT-1 cells. If the episodic rhythm represents a secretory interval as suggested by Moenter and colleagues (16), it is possible that the episodic rhythm of an activity pattern at 50–60 min intervals may be seen in primate LHRH-1 neurons, when several hours of continuous recording is conducted. In this study we only recorded action currents for up to 45 min. Alternatively, it is possible that there may be no long quiescence in primate LHRH-1 neurons. Hourly pulse-intervals of LH/LHRH-1 release in rhesus monkeys have been extensively reported (1, 6, 36, 37). We do not believe, however, that the absence of long quiescence in primate LHRH-1 neurons is due to a lack of normal afferent inputs to LHRH-1 neurons, as these neurons release the decapeptide hormone at 60 min intervals (7).

Burst firing activity appears to be a common feature in LHRH-1 neurons. In the present study we observed burst firing in primate LHRH-1 neurons at ~40 s intervals. The burst firing pattern has also been described in GT1 cells (26, 31, 38) and GFP-labeled mouse LHRH-1 neurons (13, 19, 24, 39). Comparing our data with those reported in publications, the burst frequency in monkey LHRH-1 neurons appears to be slightly slower than in mouse LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells. Moreover, burst firing patterns, such as spike number per burst and interburst intervals in primate LHRH-1 neurons were highly irregular within a single recording, in contrast to the regular firing pattern reported in mouse LHRH-1 neurons and GT1 cells. Interestingly, two of twenty primate LHRH-1 neurons showed a stereotyped pattern of rhythmic bursts, in which the first action current with the highest amplitude was followed by two to seven action currents with progressively decreasing amplitudes in a short duration (<0.1 s; Fig. 3Cc). A similar stereotyped burst firing activity has been observed in GT1 cells (26, 40). In addition, in GT1 cells each stereotyped burst activity precedes an increase in intracellular calcium, when simultaneous measurement of action currents and intracellular calcium oscillations is conducted (40). The progressively declining amplitude of action currents during bursts suggests that there is an underlying periodical fluctuation in baseline membrane potentials at ~40 s intervals in monkey LHRH-1 neurons. Nonetheless, unlike GT1 cells, each burst firing in primate LHRH-1 neurons may not lead to an increase in intracellular calcium, because the time domain of periodical bursts in primate LHRH-1 neurons is seconds, whereas the interval of calcium oscillations is several min (6). Perhaps, an irregular firing pattern, especially the irregular frequency and burst interval in primate LHRH-1 neurons may account for the difference in the mechanism of burst firing activity and the opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels that leads to an elevation of intracellular calcium concentrations. Whether a slower burst frequency in monkey LHRH-1 neurons than mouse LHRH-1 neurons represents the difference in slower pulse frequency of LHRH-1 release in primates (~60 min) than in rodents (~30 min) is unknown.

In the present study, cluster firing with multiple bursts (ranging from 60 to 420 s) was detected using Cluster7 algorithm. Cluster firing patterns with a similar time domain have also been reported in GT1-7 cells (31) and GFP-labeled mouse LHRH-1 neurons (19). Cluster rhythm appears to be endogenous in LHRH-1 neurons, as cluster firing with similar periodicity occurs in acutely isolated GFP-labeled LHRH-1 neurons (24). In a previous study we have reported that individual LHRH-1 neurons exhibit intracellular calcium oscillations with an average interval of several min (6). Therefore, in primate LHRH-1 neurons a cluster firing may correspond to an increase in intracellular calcium oscillations. Simultaneous measurement of firing patterns and intracellular calcium changes in single LHRH-1 neurons would clarify this issue.

It has been shown that a coordinated high frequency burst firing activity in multiple numbers of vasopressin and oxytocin neurons is correlated with, and a prerequisite for, neurosecretion in their posterior pituitary neuroterminals (41–45). Whether each high frequency burst activity in individual LHRH-1 neurons leads to a quantum of neurosecretion at their neuroterminals is yet to be determined. Nonetheless, the question arises: What is the cellular mechanism of LHRH-1 release, which occurs at ~60 min intervals? Our previous study suggests that individual primate LHRH-1 neurons and non-neuronal cells exhibit [Ca2+]i oscillations with independent rhythms, but [Ca2+]i oscillations in a number of neurons synchronize periodically at an interval similar to that observed for neurosecretion (6, 23). Studies with multiple microelectrode arrays suggest that even though individual GT1 cells are rhythmic, not every cell participates in each firing episode, and the sum of activities in multiple cells within a network appear to correlate with the interval of LHRH-1 neurosecretion (31, 38). Therefore, overall firing activity as a consequence of synchronization among LHRH-1 neurons (23) would determine pulsatile LHRH-1 release. In fact, the synchronization of spontaneous oscillations in [Ca2+]i among cells observed in our cultures is similar to the pattern of electrical activity that emerges in simulated networks of cells in which sparse, random activity in individual cells leads to intercellular activity waves (46). It is, therefore, hypothesized that pulsatile LHRH-1 release at ~60 min is a network property.

E2 infusion rapidly increased the firing frequency, spikes per burst, and burst duration of primate LHRH-1 neurons. Our preliminary study indicates that the membrane impermeable analog of E2, E2-BSA, also induced similar rapid E2 effects. These results complement the effects of E2 on [Ca2+]i oscillations (47). Both E2 and E2-BSA rapidly accelerated the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations in a subset of LHRH-1 neurons and resulted in more frequent synchronization among LHRH-1 neurons (47). These results suggest that the rapid effect of estrogen on firing activity of primate LHRH-1 neurons does not require E2 entry into the cell, perhaps occurring at the cell membrane level. In fact, a recent preliminary study in our laboratory shows that the membrane of LHRH-1 neurons was labeled with E2-BSA-FITC, but not BSA-FITC, suggesting the presence of estrogen binding sites on the membrane (48).

The E2-induced firing increase was blocked by the estrogen receptor blocker ICI. The results from the calcium imaging study also indicate and that the E2-induced frequency increase in [Ca2+]i oscillations is ICI sensitive, whereas the E2-induced synchronization frequency is ICI insensitive (47). As we discussed above, although the precise relationship between firing pattern with patch clamp recording and [Ca2+]i oscillations with the calcium imaging is unclear, direct stimulatory action of E2 on LHRH-1 neurons with a short latency is consistent in both studies and a part of the stimulatory effects of estrogen is ICI-sensitive. A similar ICI-sensitive membrane mediated stimulatory estrogen action on [Ca2+]i oscillations in cultured LHRH-1 neurons from mouse olfactory region has also been reported (49).

Several studies have shown the presence of ER in LHRH-1 neurons. LHRH-1 neurons express transcripts and peptides for ERβ (50–54). GT1-7 cells also express both ERα and ERβ (55, 56). Recently, we have observed that primate LHRH-1 neurons express ERβ (48). In addition, rapid action of E2 through membrane associated ERα and/or ERβ in both LHRH-1 neurons and non-neuronal cells has been reported (49, 57–59). Thus, it is possible that rapid E2 action in LHRH-1 neurons is mediated by classical ERs, perhaps ERβ. Recently, rapid action of estrogen through ERβ has been shown in mice (60). Alternatively, it is also plausible that novel membrane E2 receptors, which are pharmacologically different from classical nuclear ERs, but sensitive to ICI (61), may mediate rapid E2 action.

Nunemaker et al. (39) have examined the negative feedback effect of estrogen on firing activity of GFP-labeled LHRH-1 neurons by comparing ovariectomized mice bearing an E2 capsule for 1 week and ovariectomized controls. Results indicate that E2 stimulated the firing frequency, but also altered the episodic rhythm (low frequency rhythm) by increasing the duration of the quiescence period in a subset (~50%) of LHRH-1 neurons. Since a longer interpulse interval of pulsatile LH release with a larger pulse amplitude occurs in ovariectomized animals when compared to intact animals (62), the episodic rhythm altered by estrogen appears to represent the negative feedback effect in mouse LHRH-1 neurons (39). The question arises as to whether the stimulated firing activity by estrogen in this study is correlated with LHRH-1 neurosecretory activity. The results from a preliminary study indicate that E2 infusion for a short period induces several fold increase in LHRH-1 release for short time in our primary culture system (48).

In summary, we revealed that primate LHRH-1 neurons exhibit complex firing patterns comprised of activities with different time domains and estrogen rapidly alters firing pattern by increasing burst firing activity through a membrane associated ICI-sensitive mechanism, most likely through classical ER. The mechanism of estrogen action remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kim L. Keen, Rafael Connemara and Amanda Marsh for their technical assistance. This work is supported by NIH grants HD15433, HD11355, and RR00167.

References

- 1.Wilson RC, Kesner JS, Kaufman JM, Uemura T, Akema T, Knobil E. Central electrophysiologic correlates of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the rhesus monkey. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39:256–260. doi: 10.1159/000123988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka T, Ozawa T, Hoshino K, Mori Y. Changes in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity during the estrous cycle in the goat. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:553–561. doi: 10.1159/000127051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishihara M, Takeuchi Y, Tanaka T, Mori Y. Electrophysiological correlates of pulsatile and surge gonadotrophin secretion. Rev Reprod. 1999;4:110–116. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0040110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terasawa E 2003 Pulse generation in LHRH neurons. In: Handa R, Hayashi S, Terasawa E, Kawata M (eds) Neuroplasticity, Development, and Steroid Hormone Action. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 153–168

- 5.Terasawa E. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons: Mechanism of pulsatile LHRH release. Vitam Horm. 2001;63:91–129. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)63004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terasawa E, Schanhofer WK, Keen KL, Luchansky L. Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons derived from the embryonic olfactory placode of the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5898–5909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terasawa E, Keen KL, Mogi K, Claude P. Pulsatile release of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) in cultured LHRH neurons derived from the embryonic olfactory placode of the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1432–1441. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.3.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore JP, Jr, Shang E, Wray S. In situ GABAergic modulation of synchronous gonadotropin releasing hormone-1 neuronal activity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8932–8941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08932.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parhar IS. Cell migration and evolutionary significance of GnRH subtypes. Prog Brain Res. 2002;141:3–17. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)41080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skynner MJ, Slater R, Sim JA, Allen ND, Herbison AE. Promoter transgenics reveal multiple gonadotropin-releasing hormone-I-expressing cell populations of different embryological origin in mouse brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5955–5966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05955.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spergel DJ, Kruth U, Hanley DF, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. GABA- and glutamate-activated channels in green fluorescent protein-tagged gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2037–2050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02037.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suter KJ, Song WJ, Sampson TL, Wuarin JP, Saunders JT, Dudek FE, Moenter SM. Genetic targeting of green fluorescent protein to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: characterization of whole-cell electrophysiological properties and morphology. Endocrinology. 2000;141:412–419. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suter KJ, Wuarin JP, Smith BN, Dudek FE, Moenter SM. Whole-cell recordings from preoptic/hypothalamic slices reveal burst firing in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons identified with green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3731–3736. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeFazio RA, Heger S, Ojeda SR, Moenter SM. Activation of A-type gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2872–2891. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Estradiol feedback alters potassium currents and firing properties of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2255–2265. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moenter SM, DeFazio RA, Pitts GR, Nunemaker CS. Mechanisms underlying episodic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3022(03)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. A targeted extracellular approach for recording long-term firing patterns of excitable cells: a practical guide. Biol Proced Online. 2003;5:53–62. doi: 10.1251/bpo46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Calcium Current Subtypes in Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1914–1922. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunemaker CS, Straume M, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons generate interacting rhythms in multiple time domains. Endocrinology. 2003;144:823–831. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato M, Ui-Tei K, Watanabe M, Sakuma Y. Characterization of voltagegated calcium currents in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons tagged with green fluorescent protein in rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5118–5125. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terasawa E, Quanbeck CD, Schulz CA, Burich AJ, Luchansky LL, Claude P. A primary cell culture system of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone neurons derived from embryonic olfactory placode in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2379–2390. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML. Cluster analysis: a simple, versatile, and robust algorithm for endocrine pulse detection. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:E486–493. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.4.E486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter TA, Keen KL, Terasawa E. Synchronization of Ca2+ oscillations among primate LHRH neurons and nonneuronal cells in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1559–1567. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuehl-Kovarik MC, Pouliot WA, Halterman GL, Handa RJ, Dudek FE, Partin KM. Episodic bursting activity and response to excitatory amino acids in acutely dissociated gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons genetically targeted with green fluorescent protein. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2313–2322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02313.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusano K, Fueshko S, Gainer H, Wray S. Electrical and synaptic properties of embryonic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in explant cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3918–3922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charles AC, Hales TG. Mechanisms of spontaneous calcium oscillations and action potentials in immortalized hypothalamic (GT1-7) neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:56–64. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sim JA, Skynner MJ, Herbison AE. Heterogeneity in the basic membrane properties of postnatal gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1067–1075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01067.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellon PL, Windle JJ, Goldsmith PC, Padula CA, Roberts JL, Weiner RI. Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron. 1990;5:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90028-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krsmanovic LZ, Stojilkovic SS, Merelli F, Dufour SM, Virmani MA, Catt KJ. Calcium signaling and episodic secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in hypothalamic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8462–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosma MM. Ion channel properties and episodic activity in isolated immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. J Memb Biol. 1993;136:85–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00241492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Geusz ME, Herzog ED, Pitts GR, Moenter SM. Long-term recordings of networks of immortalized GnRH neurons reveal episodic patterns of electrical activity. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:86–93. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steiner RA, Bremner WJ, Clifton DK. Regulation of luteinizing hormone pulse frequency and amplitude by testosterone in the adult male rat. Endocrinology. 1982;111:2055–2061. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-6-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kokoris GJ, Lam NY, Ferin M, Silverman AJ, Gibson MJ. Transplanted gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons promote pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in congenitally hypogonadal (hpg) male mice. Neuroendocrinology. 1988;48:45–52. doi: 10.1159/000124988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez de la Escalera G, Choi AL, Weiner RI. Generation and synchronization of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses: intrinsic properties of the GT1–1 GnRH neuronal cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1852–1855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wetsel WC, Valenca MM, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z, Lopez FJ, Weiner RI, Mellon PL, Negro-Vilar A. Intrinsic pulsatile secretory activity of immortalized luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-secreting neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4149–4153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya AN, Dierschke DJ, Yamaji T, Knobil E. The pharmacologic blockade of the circhoral mode of LH secretion in the ovariectomized rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1972;90:778–786. doi: 10.1210/endo-90-3-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gearing M, Terasawa E. Luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) neuroterminals mapped using the push-pull perfusion method in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res Bull. 1988;21:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funabashi T, Suyama K, Uemura T, Hirose M, Hirahara F, Kimura F. Immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons (GT1-7 cells) exhibit synchronous bursts of action potentials. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;73:157–165. doi: 10.1159/000054632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Estradiol-sensitive afferents modulate long-term episodic firing patterns of GnRH neurons. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2284–2292. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costantin JL, Charles AC. Spontaneous action potentials initiate rhythmic intercellular calcium waves in immortalized hypothalamic (GT1–1) neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:429–435. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrew RD, Dudek FE. Analysis of intracellularly recorded phasic bursting by mammalian neuroendocrine cells. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:552–566. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrew RD, Dudek FE. Burst discharge in mammalian neuroendocrine cells involves an intrinsic regenerative mechanism. Science. 1983;221:1050–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.6879204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dudek FE, Tasker JG, Wuarin JP. Intrinsic and synaptic mechanisms of hypothalamic neurons studied with slice and explant preparations. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;28:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cazalis M, Dayanithi G, Nordmann JJ. The role of patterned burst and interburst interval on the excitation-coupling mechanism in the isolated rat neural lobe. J Physiol. 1985;369:45–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leng G, Brown CH, Russell JA. Physiological pathways regulating the activity of magnocellular neurosecretory cells. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57:625–655. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis TJ, Rinzel J. Self-organized synchronous oscillations in a network of excitable cells coupled by gap junctions. Network. 2000;11:299–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abe H, Keen K, Terasawa E 2003 Estrogen stimulates intracellular calcium oscillations and synchronization in LHRH neurons derived from monkey olfactory placodes. Proceedings of the 33th Annual Meetings, Society for Neuroscience (No. 15.2), November 8–12, 2003, New Orleans, LA

- 48.Abe H, Keen KL, Frost SI, Terasawa E 2005 Estrogen causes rapid stimulatory action through membrane receptors in primate LHRH neurons. Proceedings of the 87th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society (No. OR1–1), June 4–7, 2005, San Diego, CA

- 49.Temple JL, Laing E, Sunder A, Wray S. Direct action of estradiol on gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neuronal activity via a transcription-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6326–6333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hrabovszky E, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Hajszan T, Carpenter CD, Liposits Z, Petersen SL. Detection of estrogen receptor-beta messenger ribonucleic acid and 125I-estrogen binding sites in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3506–3509. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hrabovszky E, Steinhauser A, Barabas K, Shughrue PJ, Petersen SL, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Estrogen receptor-beta immunoreactivity in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons of the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3261–3264. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbison AE, Pape JR. New evidence for estrogen receptors in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:292–308. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharifi N, Reuss AE, Wray S. Prenatal LHRH neurons in nasal explant cultures express estrogen receptor beta transcript. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2503–2507. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skinner DC, Dufourny L. Oestrogen receptor beta-immunoreactive neurones in the ovine hypothalamus: distribution and colocalization with gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy D, Angelini NL, Belsham DD. Estrogen directly represses gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene expression in estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha)- and ERbeta-expressing GT1-7 GnRH neurons. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5045–5053. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro CE, Saeed SA, Murdock C, Martinez-Fuentes AJ, Arora KK, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ. Regulation of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′- monophosphate signaling and pulsatile neurosecretion by Gi-coupled plasma membrane estrogen receptors in immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1792–1804. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norfleet AM, Clarke CH, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Antibodies to the estrogen receptor-alpha modulate rapid prolactin release from rat pituitary tumor cells through plasma membrane estrogen receptors. FASEB J. 2000;14:157–165. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marquez DC, Pietras RJ. Membrane-associated binding sites for estrogen contribute to growth regulation of human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:5420–5430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERalpha and ERbeta expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abraham IM, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Critical in vivo roles for classical estrogen receptors in rapid estrogen actions on intracellular signaling in mouse brain. Endocrinology. 2005;145:3055–3061. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein- coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9529–9540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knobil E. Patterns of hypophysiotropic signals and gonadotropin secretion in the rhesus monkey. Biol Reprod. 1981;24:44–49. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod24.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]