Abstract

Ten individuals, residing in a treatment facility specializing in the rehabilitation of sex offenders with developmental disabilities, participated in an arousal assessment involving the use of the penile plethysmograph. The arousal assessments involved measuring change in penile circumference to various categories of stimuli both appropriate (adult men and women) and inappropriate (e.g., 8- to 9-year-old boys and girls). This approach extends the existing assessment literature by the use of repeated measurement and single-subject experimental design. Data from these assessments were analyzed to determine if clear and informative outcomes were obtained. Overall, three general patterns of results emerged. Some participants showed differentiated deviant arousal or higher levels of arousal to specific inappropriate stimuli (deviant is a term used in the existing sex-offender literature to describe this type of arousal). Other participants showed undifferentiated deviant arousal, in which case they showed nonspecific arousal to inappropriate stimuli. The remaining participants showed no arousal to inappropriate stimuli but did show arousal to appropriate stimuli. Implications for assessment, treatment, and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: penile plethysmograph, arousal assessment, repeated measurement, sex offenders with developmental disabilities

Recent statistics regarding child welfare in the United States report that an estimated 896,000 children were the victims of child abuse or neglect in 2002 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002). Of these cases, approximately 89,600 children (10%) were the victims of sexual abuse. Furthermore, 0.4% of the instances of sexual abuse resulted in fatalities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). These statistics, however, can be considered conservative because it is unlikely that all abuse cases are reported to the authorities.

In general, the most common perpetrators of child abuse are either the child's biological parents or other caregivers. In terms of sexual abuse, however, parents comprise less than 3% of cases. The majority of sexual abuse perpetrators consist of other relatives, followed by day-care providers, residential facility staff, and unmarried partners of parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002). Some statistics regarding very broad characteristics of sex offenders are available (i.e., age, race, etc.), but are limited due to the wide variability in this population. In general, the demographic characteristics of sex offenders seem to match those of nonoffenders. Another factor that leads to additional complications in categorizing sex offenders includes obtaining information on their intellectual functioning. The majority of the studies concerning sex offenders focus on adult or juvenile offenders without differentiating those with developmental disabilities. As a result, it is difficult to determine exactly what percentages of sex offenders have some form of developmental disability. It is generally accepted that sex offenders with and without developmental disabilities commit similar types of offenses (Day, 1994; Haaven, Little, & Petre-Miller, 1990); however, the rates of offending are found to be lower in persons with developmental disabilities (Day, 1994).

The assessment and treatment of sex offenders in general has been the focus of a long line of research encompassing numerous different approaches and conceptual frameworks. Aside from minimal variations, the methodologies used for offenders who are not developmentally disabled are also considered appropriate for developmentally disabled offenders (Haaven et al. 1990). However, as stated earlier, it is often the case that studies typically focus on sex offenders without developmental disabilities.

Historically, assessments of sex offenders have used a wide variety of procedures. One purpose of these assessments has been the measurement of an individual's sexual preference. More specifically, these assessments are designed to measure whether or not individuals show greater preference for deviant or nondeviant stimuli (e.g., children vs. adults). Early assessments typically relied on the use of self-reports or checklists. Not surprisingly, these methods were found to be unreliable and did not provide much useful information (Murphy & Barbaree, 1994).

More objective methodologies were developed during the 1950s with the advent of phallometric assessments, which measure changes in penile tumescence (Haaven et al., 1990; Howes, 2003; Laws & Marshall, 2003). Early phallometric assessments involved exposing individuals to erotic visual stimuli and measuring changes in penile engorgement (Laws & Marshall). Current assessment methods are based on the same general principles, but technological improvements have made implementation of these procedures easier.

The most commonly used and widely accepted measurement apparatus is the penile plethysmograph, which measures changes in the circumference of the penis as an indicator of sexual arousal. Currently, change in penile tumescence, as measured by the penile plethysmograph, is considered to be one of the most sensitive and reliable indicators of sexual arousal (Howes, 2003; Murphy & Barbaree, 2003). These developments in assessment methods have several advantages over previous methods in that they offer more objective, accurate, and reliable information regarding an individual's sexual preference. As a result, phallometric assessment has been a standard component in the assessment and treatment of sex offenders for approximately 50 years and is still considered to be the hallmark procedure in this area (Marshall & Laws, 2003).

Given the widespread acceptance of phallometric assessments, there are some potential limitations that must be taken into account when considering their use. Much of the literature in this area contains conflicting information regarding the utility of phallometry. One of the most critical issues involves the predictive validity of the assessments. Some studies report that arousal to deviant stimuli is considered to be one of the best predictors of reoffense (see Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004; Howes, 2003). Other studies, however, report predictive validity of phallometric assessments to be limited (see Marshall & Fernandez, 2003).

An additional issue concerns the test–retest reliability of these types of assessments. It appears that many of the studies using phallometric assessments do not involve repeated measures (Barbaree, Baxter, & Marshall, 1987). In most of these studies, the individual is exposed to the stimuli once or twice over a period of 1 or 2 days (e.g., Wormith, 1986). When repeated measures have been used, the focus has been on the reliability of the test or to evaluate treatment effects (Marshall & Fernandez, 2003; Murphy & Barbaree, 1994). It does not appear that the use of repeated measurement, a hallmark of behavior analysis, has been used or even considered as an appropriate assessment method in its own right. Thus, an integrated methodology involving the use of the penile plethysmograh and repeated measurement is needed. Such an approach could be costly in terms of both time and money, but the benefits of a more stable and reliable assessment outcome may outweigh the costs.

The problem of assessment involving developmentally disabled sex offenders is considered to be a great challenge across the United States and in other countries (see Gardner, Graeber, & Machkovitz, 1998). The treatment facility in the current study is unique in that it focuses on rehabilitating individuals with developmental disabilities who have committed some felony offense, which in most cases was a felony sexual offense. One component of a large and complex assessment and treatment package for these individuals involves arousal assessments using the penile plethysmograph. Furthermore, the arousal assessments conducted at this facility involve the use of repeated measures. Each individual who participates in these assessments is exposed to the stimulus materials several times across days or even weeks, with the results being used to help make decisions regarding treatment, appropriate placement, and discharge. To our knowledge, there has only been one published report of phallometric assessments using repeated measurement with developmentally disabled sex offenders (Rea, DeBriere, Butler, & Saunders, 1998).

The information provided by phallometric assessments can be useful on a number of levels. Similar to the assessment methodology developed by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982/1994) that is designed to determine the conditions under which a targeted behavior is likely to occur, phallometric assessments help to determine the conditions under which an arousal response is more likely to occur. By isolating the variables responsible for arousal, phallometric assessments help to point to a more specific treatment focus. For example, the outcomes of a phallometric arousal assessment may indicate that a particular individual is differentially aroused in the presence of boys ranging in age from 6 to 7 years. With this information, interventions can then be specifically designed to target this particular demographic category.

A commonly attempted intervention to decrease inappropriate sexual arousal has been to pair the arousal to a specific age category with some aversive stimulus, typically an unpleasant smell. Whereas these types of treatments are considered fairly standard for sexual offenders, the findings tend to be mixed and should be subjected to additional evaluation (see Laws & Marshall, 2003). In general, the most effective treatments for sexual offenders have yet to be discovered. One reason for these equivocal results might be that insufficient baselines have been collected as a point of comparison. Again, the use of repeated measurement may be useful in this regard.

By using an assessment method that follows the same logic as that of functional analysis, parallel treatments models can be developed. For example, if the outcome of a functional analysis points to a negative reinforcement function, certain procedures such as time-out would be avoided and other procedures would be recommended (e.g., differential negative reinforcement). Similarly, an arousal assessment that indicates deviant arousal also suggests logical treatment directions to use or to avoid. For example, clinicians may attempt to decrease arousal to the targeted stimulus or stimuli and also to increase interest in adult stimuli while teaching the client the necessary social skills to develop relationships.

Furthermore, arousal assessments that involve repeated measurement could potentially be valuable in that they would provide a more comprehensive picture of an individual's arousal by assessing changes in or determining the stability of arousal patterns across time. For example, variables that could affect an individual's arousal on any given day (e.g., lack of sleep, emotional responding, masturbation practices, etc.) would be less likely to distort the overall outcomes in that the assessments are conducted across multiple days. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate data from arousal assessments conducted at a state residential treatment facility to determine if any clear or informative outcomes could be obtained.

Method

Participants

The data from 10 individuals in a state residential treatment facility for developmentally disabled offenders were included in the current study. The participants were assigned numbers by the clinical staff so that the data could be reviewed without identifying information. All of these individuals had been accused of committing one or more sexual offenses and had been found incompetent to stand trial. As a result, the charges were dismissed, and they were placed in a state residential treatment facility. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics for the participants. All of these individuals consented to participate in the arousal assessments. Approval was obtained from the facility institutional review board (IRB), the university IRB, and the IRB used by the Florida Department of Children and Families and Agency for Persons with Developmental Disabilities to evaluate the data from the assessments (note that these assessments have been a standard component of the evaluation process at the residential facility and, therefore, were not conducted for the purposes of research).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Offense Descriptions for All Participants.

| Participant | Age | IQ | Diagnosis | Offense |

| 1 | 34 | 60 | Mild mental retardation | Six counts of sexual battery on a child under the age of 12; one count of sexual performance by a child under the age of 12 |

| 7 | 27 | 60 | Mild mental retardation | Attempted sexual battery and lewd assault on a child under the age of 16 |

| 19 | 34 | 67 | Mild mental retardation | Sexual battery on a minor under the age of 12 |

| 22 | 38 | 69 | Mild mental retardation | Two counts of sexual battery on a child; two counts of performing a lewd act on a child |

| 27 | 42 | 53 | Mild mental retardation | Capital sexual battery on a child under the age of 12 |

| 34 | 29 | 53 | Mild mental retardation | Sexual battery on a child under the age of 12 |

| 37 | 42 | 60 | Mild mental retardation | Kidnapping a child under the age of 13; two counts of lewd and lascivious indecent assault on a child under the age of 16 |

| 38 | 55 | 73 | Mild to borderline mental retardation | Two counts of battery on a child under the age of 12 |

| 44 | 26 | 64 | Mild mental retardation | Six counts of sexual battery on a child under the age of 12 |

| 47 | 53 | 57 | Mild mental retardation | Multiple counts of rape and murder involving children ranging in age from 12 to 18 |

Arousal Assessment

The arousal assessments involved measuring an individual's arousal to various types of stimuli through the use of the penile plethysmograph. The penile plethysmograph consists of a penile strain gauge that is worn around the penis, with an output to a computer that allows a technician to track real-time changes in penile circumference. A change in penile circumference is taken as an indication of an individual's arousal and is measured in the presence of different stimuli considered to be both appropriate (nondeviant) and inappropriate (deviant). All of the arousal assessments reported in the current study were originally conducted or supervised by a certified penile plethysmograph technician or clinician.

The assessments involved the use of a circumferential mercury-in-rubber strain gauge (D. M. Davis Inc.) connected to a computerized interface. The stimuli were commercially available and produced by Northwest Media Inc. These stimuli were designed specifically for the assessment of sexual arousal. The stimulus package consisted of 10 video clips that were each exactly 2.5 min in duration, and contained either a male or female of a particular developmental age (kindergarten, 6 to 7, 8 to 9, teen, or adult) engaging in a range of behavior (not intended to be sexually explicit) while wearing a bathing suit. For example, each individual was shown reading a magazine, walking, eating a piece of fruit, sitting on the edge of a pool with their feet splashing in the water, and drying off with a towel. The package also contained an additional stimulus designed to be neutral and involved scenes of boating and fishing. In some early cases, the participants were exposed to a sexually explicit adult stimulus; however, due to state-level recommendations, such material was not used in later cases.

Before beginning the assessment, each individual was required to take a measure of the circumference of his penis in order to ensure that the appropriate gauge size would be selected. The participants were also instructed on how to apply the gauge and where it should be located on the penis. The sessions were conducted in a room (2 m by 2.5 m) that contained a recliner, a television screen used to present the video clips, a camera that provided a live video feed of the participant from above the shoulders, and a metal lap tray. The technicians were in an adjacent room that contained a computer, a video monitor showing the live feed, and a video cassette recorder to present the stimuli.

Before each session, the technician was required to calibrate the penile strain gauge to ensure accurate measurement. This involved systematically measuring changes in the range of each gauge and matching the measurements with the computer readings. The technician also placed a disposable absorbent pad on the recliner and placed the gauge on top of the pad. At the beginning of each session, the participant was prompted to use the bathroom and given an opportunity to do so if necessary. In addition, the participant was asked when he had last masturbated, and the technician recorded the information. Once inside the session room, the participant was instructed to pull his pants and underwear down to his ankles, sit down in the chair and apply the penile strain gauge. Once the gauge was applied, the participant was instructed to place the metal tray over his lap and place his hands on the tray. The purpose of the tray was to eliminate any visual feedback of arousal and to decrease the likelihood that the participant would interfere with the gauge. To ensure privacy, the live video feed remained off until the participant reported that he was ready to begin the session. If the participant attached the gauge incorrectly or if any other problems occurred during a session (i.e., the gauge broke), they were easily detectable based on the pattern shown in the data stream.

During the session, the technician monitored the real-time changes in penile circumference via the computer screen. The video clips were presented one at a time in one of three predetermined orders. Before the presentation of each clip, a detumesence and stability criterion of no changes greater than 5 mm for a period of 1 min had to be met. The technician recorded the circumference of the penis in millimeters at the beginning of the stimulus presentation and the circumference at the highest point during the stimulus presentation. The difference in these two measures served as the change in penile circumference during each video clip. After all of the clips had been presented, the participant was instructed to remove the gauge, get dressed, wash his hands, and exit the room. One session was conducted per day, and each session involved one presentation of each stimulus. Sessions were typically conducted three to five times per week. The total number of sessions conducted with each participant varied, but each assessment involved multiple sessions.

Data Analysis

The data from the repeated measures were retrospectively analyzed to evaluate whether the arousal assessments produced any reliable and informative outcomes. The raw data from the assessments were organized and plotted on a session-by-session basis using a multielement design. The data were also plotted so that comparisons could be made across gender and age stimuli. Visual inspection was used to determine if the data showed any consistent patterns or trends. Although clinical assessments may have involved dozens of sessions, all of the raw data were plotted only until clear results were evident.

Results

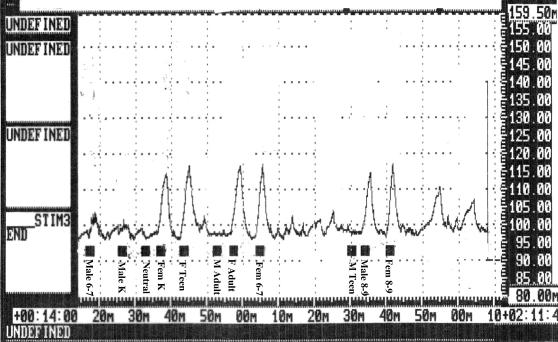

Figure 1 shows an example of the real-time data obtained from a single arousal-assessment session. The relevant points of comparison involve the changes in circumference of the penis during the stimulus presentations. For example, the change during the presentation of the male kindergarten stimulus (second bar) is less than the change during the female kindergarten stimulus (fourth bar).

Figure 1. Printout showing the results of an arousal assessment.

The data path represents real-time changes in penile circumference in response to the presentation of the stimuli. The stimulus presentations are indicated by the solid bars underneath the data path. The numbers on the right side of the figure represent millimeter change in penile circumference.

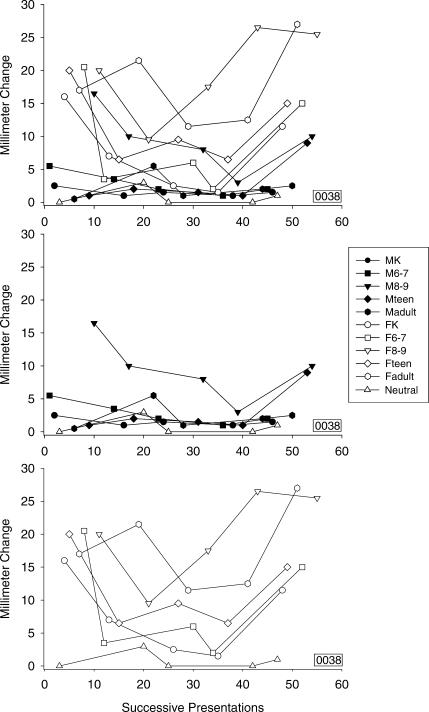

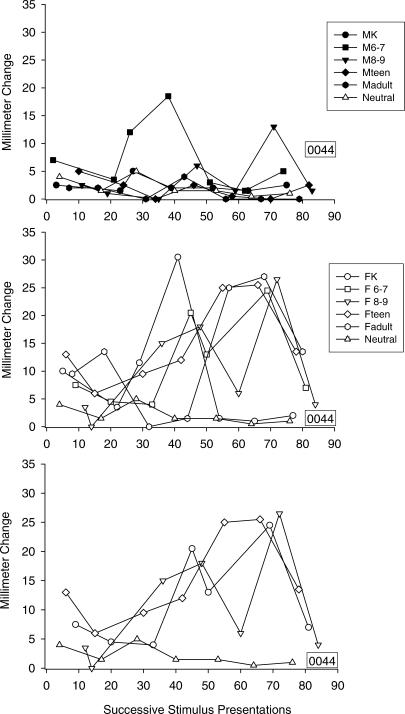

Representative data from the arousal assessments are shown in Figures 2 through 6. All data are plotted in terms of millimeter change in penile circumference across successive presentations of the deviant and nondeviant stimuli used in the assessment. Figure 2 shows the results from the arousal assessments for Participant 38. Arousal levels to the male stimuli (middle) were generally low except for the male 8–9 category, which was consistently higher than the other age groups and consistently higher than the neutral stimulus. Higher overall levels of arousal were evident to the female stimuli (bottom), but the arousal was differentially higher in the presence of the female 8–9 stimulus and to the female adult stimulus. In most cases, arousal in the presence of these stimuli was higher than in the presence of any of the other stimuli and was consistently higher than in the presence of the neutral stimulus in all cases.

Figure 2. Assessment results for Participant 38 (top).

The same assessment results grouped by the male stimuli (middle) and the female stimuli (bottom).

Figure 3. Assessment results for Participant 38 separated by age and gender.

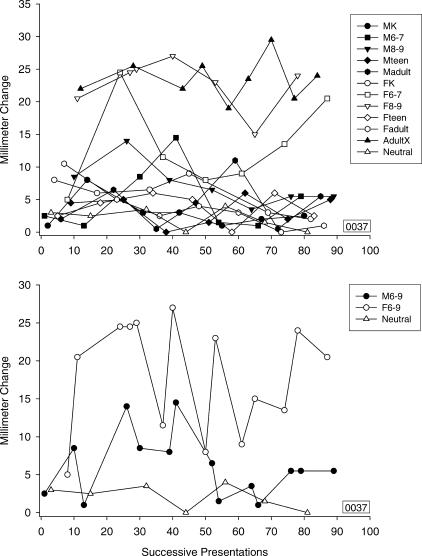

Figure 4. Assessment results for Participant 37 (top).

Assessment results grouped together by age categories 6–9 (bottom).

Figure 5. Assessment results for Participant 34 to the male stimuli (top) and female stimuli (middle).

Comparison of assessment results between males and females ranging in age from kindergarten to 7 years (bottom).

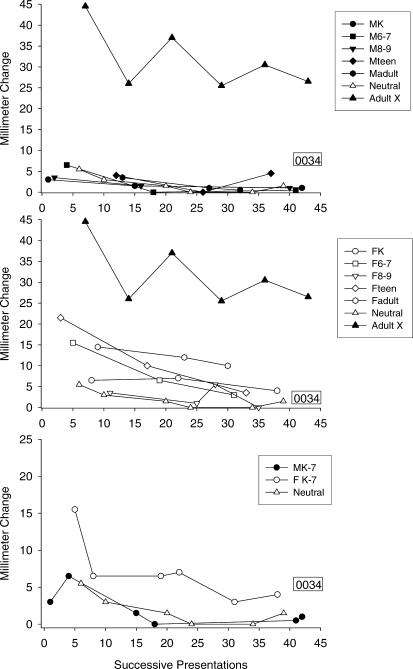

Figure 6. Assessment results for Participant 44 to the male stimuli (top) and female stimuli (middle).

Assessment results grouped together by the highest female age categories (bottom).

Figure 3 shows an example of some of the additional analyses that were conducted, again using data from Participant 38. In this case, comparisons were made between gender at each age category as well as with the neutral stimulus. Across the majority of sessions, arousal to the female stimuli was higher than to the male stimuli and to the neutral stimulus. In the 8–9 age category, arousal levels to the male stimulus were higher than in previous age categories; however, arousal levels to the female stimulus remained higher in all but one instance. Overall, results for this participant show differential arousal to females, for both deviant and adult stimuli, and arousal to males in the 8–9 age category.

Figure 4 shows the arousal assessment results for Participant 37. High levels of arousal were evident for the female 6–7, female 8–9, and the sexually explicit adult stimulus. Arousal levels in the presence of these stimuli were higher than to the neutral stimulus in all cases. Furthermore, arousal levels to the female 8–9 stimulus were higher than to all of the other stimuli (except for the sexually explicit adult stimulus) in all but one session when arousal levels to the female 6–7 stimulus reached similar levels. The bottom panel shows a gender comparison between the two age categories that produced the highest levels of arousal grouped together plotted against the neutral stimulus. Arousal levels to the female 6–9 category (created by combining data from the 6–7 and 8–9 age groups) were usually higher than arousal levels to the males and consistently higher than the neutral stimulus. Therefore, in this case, arousal to females ranging in age from 6 to 9 years was differentiated from other age and gender categories as well as from the neutral stimulus.

Figure 5 shows the arousal-assessment results for Participant 34. The top panel shows the results to the male stimuli, the neutral stimulus, and the explicit adult stimulus. In this case, arousal to all of the male categories was undifferentiated from the arousal that occurred in the presence of the neutral stimulus, and the highest levels of arousal occurred in the presence of the sexually explicit adult stimulus. The middle panel shows the arousal to the female stimuli compared to neutral and to the sexually explicit adult stimulus. Arousal to all but one category of the female stimuli (female 8–9) reached higher overall levels than and was differentiated from arousal to the neutral stimulus. Also for this participant, a decreasing trend was evident in the arousal levels to both the sexually explicit adult stimulus and all of the female stimuli. The bottom panel shows a comparison between males and females from the kindergarten and 6–7 categories grouped together and plotted against the neutral stimulus. Although the overall arousal levels are generally low (relative to other arousal levels seen with some individuals), arousal to the female stimuli was higher than to the male stimuli and the neutral stimulus in all cases, whereas arousal to the male stimuli matched the neutral stimulus.

Figure 6 shows the results of the arousal assessment for Participant 44. Low overall levels of arousal were evident to the male stimuli (top) with the exception of two high points to the male 6–7 stimulus and one high point to the male 8–9 stimulus. Arousal levels to the other stimuli fluctuated around the same levels as the neutral stimulus. Higher overall levels of arousal were evident to the female stimuli (middle), and arousal to the majority of the female stimuli, except for the female kindergarten stimulus, was higher than to the neutral stimulus. The bottom panel shows arousal to the three deviant female stimuli that generated the highest levels of arousal plotted against neutral. Arousal was differentially higher to the female stimuli, but among the female stimuli, arousal reached similar levels among the kindergarten, 8–9, and teen stimuli.

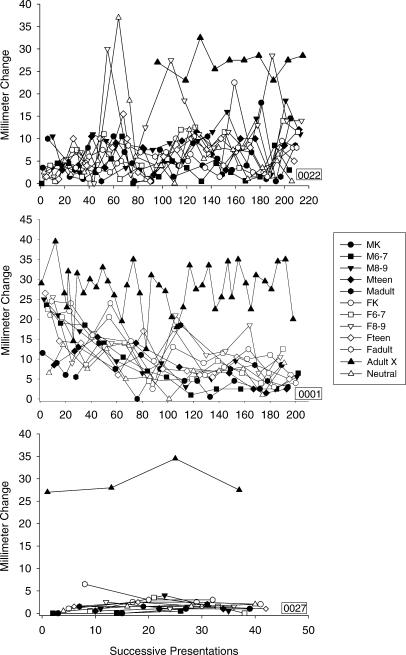

Figure 7 shows the results of the arousal assessment for Participants 22, 1, and 27. Participant 22 showed high levels of arousal to both deviant and nondeviant stimuli. The highest levels of arousal occurred in the presence of the sexually explicit adult stimulus. Arousal to the deviant and nondeviant stimuli was evident, but no systematic differentiation occurred between the various age categories or the neutral stimulus. Participant 1 also showed the highest levels of arousal in the presence of the sexually explicit adult stimulus. No clear differentiation among the other stimuli compared with each other and with the neutral stimulus was apparent. There was also a decreasing trend in the overall arousal levels to the stimuli (except for the sexually explicit adult stimulus) during the first part of the assessment, after which the levels stabilized. Participant 27 did not show arousal to any of the deviant or nondeviant age categories. There is no clear separation among the gender or age categories or the neutral stimulus. High levels of arousal occurred only in the presence of the sexually explicit adult stimulus. Data for Participant 27 are representative of three other outcomes showing no deviant arousal (Participants 7, 19, and 47).

Figure 7. Assessment results for Participant 22 (top), Participant 1 (middle), and Participant 27 (bottom).

Discussion

Overall, three general patterns of results from the arousal assessments were evident: differentiated deviant arousal, undifferentiated deviant arousal, and no deviant arousal. Four of the participants (37, 38, 34, and 44) showed differentiated deviant arousal. Differentiated deviant arousal was characterized as showing arousal in the presence of a particular age and gender category that was higher than the arousal to other categories and to the neutral stimulus. In all four of these cases, levels of arousal were consistently higher to particular age categories, gender categories, or both. Furthermore, the differentiated arousal patterns were also consistently higher than arousal levels to the neutral stimulus.

Two of the participants (22 and 1) showed undifferentiated deviant arousal patterns. Undifferentiated deviant arousal was characterized as showing similar arousal levels to deviant and nondeviant stimuli that was higher than the arousal in the presence of the neutral stimulus. For these participants, arousal levels to both the deviant and nondeviant stimuli reached similar levels and were higher than to the neutral stimulus in most cases. However, the arousal levels to the deviant stimuli were not higher in the presence of any particular age or gender category (except for the sexually explicit adult stimulus).

Four of the participants (7, 19, 27, and 47) did not show any arousal to the deviant stimuli. In these cases, arousal levels in the presence of the child stimuli were similar to the levels shown in the presence of the neutral stimulus. All of these individuals did, however, show arousal to the sexually explicit adult stimulus. (Only the data from Participant 27 are presented because they show representative patterns for the other participants who fell into this category.)

Despite the issues that surround the predictive validity of arousal assessments, the current analysis suggests that such assessments can yield clear outcomes with sex offenders who are developmentally disabled. Furthermore, by using repeated measurement, more definitive conclusions can be drawn. For example, treatment decisions based on only one or two sessions of the assessment for Participant 38 would likely have been different from decisions based on the complete assessment. By the second session, the highest levels of arousal occurred in the presence of the appropriate female stimulus, and other levels of arousal were mixed. By the end of the assessment, it was clear that high levels of arousal also occurred in the presence of the female 8–9 stimulus.

The data from Participants 34 and 1 are unique in that they show a decreasing trend in arousal across repeated exposures to the stimuli. This may illustrate a possible limitation of conducting assessments using repeated measures. Repeatedly exposing individuals to the same stimuli may lead to habituation of their arousal response. Alternatively, this decreasing trend may also be a product of respondent extinction resulting from the repeated presentation of the visual stimulus in the absence of any sexual stimulation. In this study, only 2 of 10 participants exhibited this pattern of responding, suggesting that it may not be a widespread problem. Regardless, future studies using repeated measures should take into account this possibility.

Taken as a whole, the arousal assessments showed that not all of the participants were differentially aroused by the deviant stimuli. The participants who did not show any arousal to the standard stimuli included in the package (i.e., all the stimuli except for the sexually explicit adult stimulus) are perhaps the most difficult to interpret. Numerous possibilities could produce such an outcome. For example, in some cases, individuals may not be able to become aroused under the assessment conditions. In other cases, the participants may not find any of the stimuli sexually stimulating, or they may find the stimuli arousing but have learned to suppress arousal during the assessment. Because arousal occurred in the presence of explicit material, it is clear that participants were capable of becoming aroused under the assessment conditions and that the equipment was working properly. In other cases, testing arousal to sexually explicit stimuli can be useful in determining an individual's maximum level of arousal and how that compares to arousal generated by other stimuli. However, due to the controversial nature of showing sexually explicit stimuli, they are typically no longer in use (Scott, 1997).

The information from arousal assessments might be used clinically in a number of ways. First, specific targets for teaching are identified. Thus, skills training can be conducted to teach avoidance of high-risk situations (e.g., being in situations with children of a certain age group). Second, the assessment results could be used to evaluate the effects of commonly used, but poorly validated, treatments. For example, classical conditioning, which typically involves pairing unpleasant odors with deviant arousal, has been commonly used (Marshall & Laws, 2003). Yet, because no studies on the classical conditioning approach have been conducted using individual arousal baselines, to date it is not possible to evaluate whether those procedures actually change arousal (especially outside the laboratory). Third, novel approaches to treatment could be evaluated. For example, the effects of presession masturbation could be tested to determine whether ejaculation serves as an establishing operation or an abolishing operation for sexual stimuli as reinforcing (or at least as arousing stimuli). Fourth, arousal assessments could be used as one component of a risk assessment. For example, if a client continues to show high arousal to children over time, he may be considered too high a risk for reentry into a community placement. Of course, the inverse is not necessarily true: A man who shows no deviant arousal cannot be presumed to be low risk. Only future research on the potential utility of plethysmograph assessments will point to the most appropriate clinical usage. By taking a functional approach to assessment, however, clinicians will likely be in a better position to design treatments that take into account the variables that contribute to an individual's deviant arousal.

Whatever use of plethysmograph assessments ultimately proves useful, a question remains as to how well the arousal outcomes obtained in the laboratory actually represent levels of arousal that may occur in the community. One technical advance in this area has been the development of a portable plethysmograph (e.g., Rea et al., 1998), which allows arousal assessments to occur in natural settings. The device is discreetly worn by the individual and records changes in penile circumference to environmental events (e.g., a child walks by the individual at a store). Having information from a regular and portable penile plethysmograph could potentially be useful in determining the reliability and stability of an individual's arousal and provide more support for possible treatment decisions (e.g., factors related to generalization and maintenance). Of course, such research would open up a host of ethical considerations.

Furthermore, it is important for future researchers to investigate arousal to appropriate and inappropriate stimuli with typically developed individuals without any history of sexual offenses. Although some research of this sort has been conducted (see Murphy & Barbaree, 1994), no studies have been done using single-subject methods. Such information may help to identify the mechanisms that lead to committing a sexual offense. For example, it may be the case that typical men show at least some arousal to some of the inappropriate stimuli, but they have no previous history of committing a sexual offense. They may be aroused by a child in the community and have an opportunity to get the child alone, but do not act on it. An individual from the population in the current study, however, has acted on such an opportunity. Thus, operant features of the problematic behavior would need to be addressed.

To conclude, the methodological approach taken in this study highlights a potential contribution of single-subject methodology for the assessment of sex offenders with developmental disabilities. Other researchers in the field of sex offender assessment may benefit from a working knowledge of single-subject experimental logic. For example, it is conceivable that modest effects reported in prior studies that are statistically significant are a result of pronounced effects with some individuals mixed with noneffects with other individuals. Conversely, noneffects may wash out important effects in some evaluations. Single-subject methodology permits an analysis at the level of individual behavior and, of course, does not require that the evaluation be limited to 1 subject only. In fact, we recommend that future research could be designed to assess large numbers of individual sex offenders and possibly compare them to those who are not sex offenders, but each analysis could occur in the context of a single-subject analysis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a contract with the Florida Agency for Persons with Disabilities; however, opinions do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agency. We thank Laura Heston for her help with the data analysis.

References

- Barbaree H.E, Baxter D.J, Marshall W.L. The reliability of the rape index in a large sample of rapists and nonrapists. 1987. Unpublished manuscript. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day K. Male mentally handicapped sex offenders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;165:630–639. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W.I, Graeber J.L, Machkovitz S.J. Treatment of offenders with mental retardation. In: Wettstein R.M, editor. Treatment of offenders with mental disorders. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 329–364. In. Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Haaven J, Little R, Petre-Miller D. Treating intellectually disabled sex offenders: A model residential program. Orwell, VT: The Safer Society Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R.K, Morton-Bourgon K. Predictors of sexual recidivism: An updated meta-analysis (Cat. No. PS3-1/2004-2E-PDF) Public Works and Government Services Canada (ISBN: 0-662-36397-3); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howes R.J. Circumferential change scores in phallometric assessment: Normative data. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2003;15:365–375. doi: 10.1177/107906320301500411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws D.R, Marshall W.L. A brief history of behavioral and cognitive behavioral approaches to sexual offenders: Part 1. Early developments. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2003;15:75–92. doi: 10.1177/107906320301500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W.L, Fernandez Y.M. Phallometric testing with sexual offenders: Theory, research, and practice. Brandon, VT: The Safer Society Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W.L, Laws D.R. A brief history of behavioral and cognitive behavioral approaches to sexual offenders: Part 2. The modern era. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2003;15:93–120. doi: 10.1177/107906320301500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy W.D, Barbaree H.E. Assessments of sex offenders by measures of erectile response: Psychometric properties and decision making. Brandon, VT: The Safer Society Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rea J.A, DeBriere T, Butler K, Saunders K.J. An analysis of four sexual offenders' arousal in the natural environment through the use of a portable penile plethysmograph. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 1998;10:239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Scott L.K. Community management of sex offenders. In: Schwartz B.K, Cellini H.R, editors. The sex offender: New insights, treatment innovations and legal developments. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 1997. pp. 16-1–16-11. In. Eds. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Child maltreatment (On-line) 2002. Available: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/publications/cmreports.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Wormith J.S. Assessing deviant sexual arousal: Physiological and cognitive aspects. Advances in Behavior Therapy. 1986;8:101–137. [Google Scholar]