Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the relationship between breastfeeding and resumption of vaginal intercourse; to determine the association between these behaviours and age, parity, marital status, mode of delivery, and contraceptive use; and to identify factors associated with resumption of intercourse among Canadian women in the early postpartum period.

DESIGN

Prospective survey.

SETTING

Eleven obstetricians’ offices in three Ontario communities between August and December 2002.

PARTICIPANTS

Women attending their first postpartum visit.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Resumption of vaginal intercourse.

RESULTS

Of 316 respondents, 181 (57.3%) were currently breastfeeding, and 167 (52.8%) had not yet resumed vaginal intercourse. Mean age of the mothers was 28.7 ± 5.3 years; mean age of their babies was 6.5 ± 1.1 weeks. This was a first child for 50.3% and a second child for 32.6%. Most women (72.8%) were married; another 19.3% were in common-law relationships. Married women were more likely to breastfeed (P = .001), as were those with higher parity (P = .008). Multivariable logistic regression identified five variables significantly associated with resumption of intercourse by 6 weeks post partum. The two most statistically significant variables were breastfeeding (exclusively or supplementing with bottle) and baby’s age in weeks (P <.001 for both). Mode of delivery (vaginal delivery with no tearing, compared with cesarean section or vaginal delivery with tearing) was also a highly significant predictor (P = .003), as was higher parity (P = .003). Older maternal age was weakly associated with resumption of intercourse (P = .049). The 167 women who had not resumed intercourse were asked to indicate their main reasons: 161 responded, citing a total of 215 reasons (54 cited more than one reason). The most common reasons were lack of interest (18.6%), being too tired (16.8%), being afraid of intercourse being painful (16.8%), physician told them not to (15.6%), and thinking they should wait 6 weeks (14.4%).

CONCLUSION

Breastfeeding women who delay resumption of intercourse during the postpartum period might benefit from open discussion of breastfeeding, sexuality, and contraception immediately post partum.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Examiner la relation entre l’allaitement maternel et la reprise des rapports sexuels vaginaux; établir la relation entre ces comportements et les facteurs âge, parité, situation matrimoniale, type d’accouchement et usage de contraceptifs; identifier les facteurs associés à la reprise des rapports sexuels chez les Canadiennes ayant accouché récemment.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête prospective.

CONTEXTE

Cabinets de 11 obstétriciens dans trois localités ontariennes, entre août et décembre 2002.

PARTICIPANTES

Femmes à leur première consultation postpartum.

PRINCIPAL PARAMÈTRE ÉTUDIÉ

Reprise des rapports sexuels vaginaux.

RÉSULTATS

Sur les 316 répondantes, 181 (57,3%) allaitaient et 167 (52,8%) n’avaient pas encore eu de rapports sexuels vaginaux. Les femmes étaient âgées en moyenne de 28,7 ± 5,3 ans et leur bébé de 6,5 ± 1,1 semaines. C’était un premier bébé dans 50,3% des cas et un second dans 32,6% des cas. La plupart des femmes étaient mariées (72,8%) ou vivaient en couple (19,3%). Les femmes mariées étaient plus susceptibles d’allaiter (P = .001), de même que celles ayant la plus grande parité (P = .008). La régression logistique multifactorielle a identifié cinq variables qui avaient une association significative avec la reprise des rapports sexuels 6 semaines après l’accouchement. Les deux variables les plus significatives du point de vue statistique étaient l’allaitement maternel (exclusif ou complété par le biberon) et l’âge en semaines du bébé (P < .001 pour les deux). Un autre facteur prédictif très significatif était le type d’accouchement (vaginal sans déchirure vs césarienne ou accouchement vaginal avec déchirure; P = .003) ainsi que la plus forte parité (P = .003). Une faible association existait entre la reprise des rapports sexuels et un âge maternel plus élevé (P = .049). On a demandé aux 167 femmes qui n’avaient pas repris les rapports sexuels d’indiquer leurs principales raisons : les 161 répondantes ont indiqué 215 raisons, 54 en citant plus d’une. Les raisons les plus fréquentes étaient un manque d’intérêt (18,6%), une trop grande fatigue (16,8%), la crainte de rapports douloureux (16,8%), les conseils en ce sens du médecin (15,6%) et la croyance qu’elle devaient attendre 6 semaines (14,4%).

CONCLUSION

Les femmes allaitant qui retardent la reprise des rapports sexuels après l’accouchement profiteraient d’une franche discussion sur l’allaitement maternel, la sexualité et la contraception immédiatement après l’accouchement.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

There is conflicting evidence regarding the effect of breastfeeding on sexuality post partum. Studies show more interest, less interest, and no change in patterns of intercourse. Most studies are retrospective.

This prospective study found a significant delay in resumption of sexual activity among breastfeeding women compared with bottle-feeding women.

Family physicians are encouraged to discuss the issues around breastfeeding and sexuality during postpartum visits.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

L’effet de l’allaitement maternel sur la sexualité dans le postpartum fait l’objet d’une controverse. Les différentes études (la plupart rétrospectives) ont trouvé soit une augmentation, une diminution de l’intérêt ou aucun changement du type de rapport sexuel.

Dans cette étude prospective, on a observé que l’allaitement maternel causait un retard significatif de la reprise de l’activité sexuelle comparé à l’allaitement artificiel.

Les auteurs incitent le médecin de famille à discuter de la relation allaitement maternel/sexualité au cours des visites postpartum.

Pregnancy, delivery, and motherhood have a great effect on women as sexual beings. Many women choose to breastfeed their infants, and this choice could strongly affect the sexuality of couples during the postpartum period and beyond. Information on breastfeeding and its relationship with sexuality is inconsistent. This information is needed to counsel patients effectively on expected changes and adjustments after delivery.

Avery et al1 reported that 71.1% of primiparous women interviewed during postpartum hospitalization said it was somewhat, quite, or extremely important that their sexual interest returned rapidly after delivery. Many women who seek sex therapy report that problems started after the birth of a child.2 A large number of women experience sexual problems following childbirth, up to 43% in one study,3 yet only a few of these women (15%) discuss these problems with health professionals.4 This could indicate a lack of communication between patients and their physicians with regard to postpartum sexuality.

In one study, 29% of women reported that they had discussed with their doctors resumption of intercourse, but only 18% were advised about possible problems and changes in sexuality post partum.4 In another study, only 16.8% of women could recall receiving advice on sexual activity during the puerperium,5 even though discussion of breastfeeding and postpartum sexuality should be part of complete obstetric care.

Interest in sexual activity often decreases throughout pregnancy, but eventually returns after delivery.6-8 Average time to resumption of intercourse ranged from 5 to 8 weeks after delivery in most studies,3,5,6,8-11 many of which relied on retrospective reports.6,8-11 The most common reasons cited for delaying resumption of intercourse after delivery included pain, lack of desire, vaginal bleeding or discharge, fatigue, vaginal dryness, fear of infection, or issues around pregnancy and self-image.2

There is also conflicting information about the effect of breastfeeding on sexuality. Two studies identified a positive effect. Breastfeeding women reported increased sexual desire and activity over their prepregnant state,12 possibly related to larger breast size, direct physical stimulation, and increased sensitivity.1 Breastfeeding, however, has been associated with dyspareunia.4,10,13

Other studies have shown that breastfeeding women are significantly more likely to report lack of sexual desire than non-breastfeeding women,1,3,8,9,13 and that following weaning, primiparous women experience an increase in both sexual desire and coital frequency.14 Three quarters of the women surveyed by Kenny reported that breastfeeding “had little effect” on their sexual lives.15 More recently, Avery et al noted that 74.6% of primiparous women at 1 month post partum said that combining breastfeeding and a sexual relationship was “not a problem” although, after weaning, 45.3% said that breastfeeding had interfered with their relationships.1

Data on breastfeeding and the timing of resumption of intercourse post partum are conflicting. Alder and Bancroft reported 5.8 weeks before resumption of intercourse for non-breastfeeding women and 6.9 weeks for breastfeeding women13 while Byrd and associates reported 6.9 and 7.8 weeks, respectively.8 Grudzinskas and Atkinson, however, found no association between breastfeeding and resumption of intercourse.5 All three studies were based on retrospective data collected at 3 months or 12 months post partum and included only married, primiparous women.

The purpose of this study was to prospectively describe the association between breastfeeding and resumption of intercourse at the time of the first postpartum visit. Associations between these activities and age, parity, marital status, mode of delivery, and contraceptive use were also assessed. In addition, reasons for delaying intercourse were examined to increase understanding about postpartum sexuality.

METHODS

All women making their first postpartum visit to one of 11 obstetricians in Belleville, Oshawa, and Peterborough, Ont, between August and December 2002 were invited to participate. This was a convenience sample, but we thought that collecting data for 5 months would provide a sufficient sample size for meaningful comparisons. There were no exclusion criteria.

Women were given an information letter and a one-page questionnaire. Data were sought on age, parity, marital status, mode of delivery, and age of baby. Breastfeeding groups were defined as breastfeeding exclusively, breastfeeding with supplementation, breastfeeding discontinued, or never breastfed. Women were also asked whether they had resumed vaginal intercourse and if so, which method of contraception they used. Women who had not resumed intercourse were asked to state the main reason. No identifying information was collected, and surveys were collected immediately in sealed envelopes. No information was collected on non-participants in order to avoid burdening clinic staff.

Relationships between resumption of intercourse and other variables were assessed by chi-square tests (categorical variables) and t tests (continuous data). Stepwise logistic regression was used to identify the combination of variables predictive of resumption of intercourse. Continuous data were not recoded to binary outcomes. Variables with P values of .2 or less in bivariate analyses were put into the multivariable model; the stepwise procedure was used to enter (P ≤ .05) and remove (P > .1) variables from the model. All references to statistical significance in the following text are based on an alpha of ≤ .05. The study was approved by the Queen’s University and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Human Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

Of the 316 surveys collected, 46.8% were from Belleville, 46.8% were from Oshawa, and 6.3% were from Peterborough. Clinic staff indicated that most women (>80%) were willing to complete the short survey while they waited for their appointments.

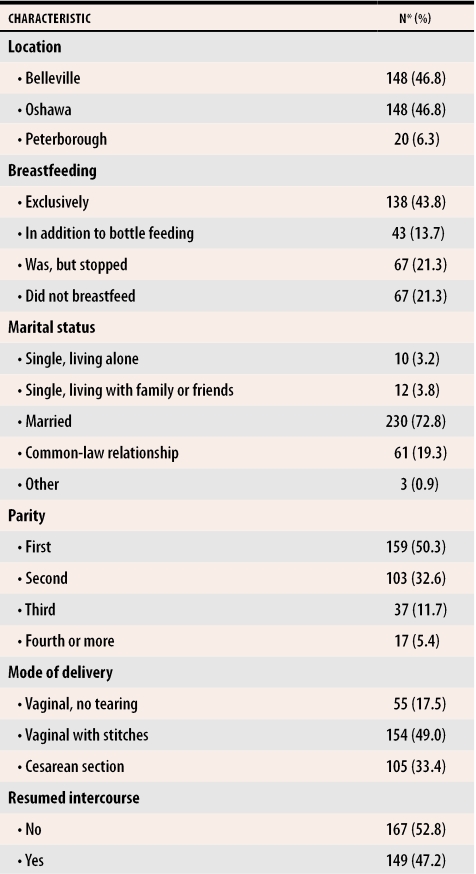

Respondents’ ages ranged from 16 to 41 years, with a mean of 28.7 ± 5.3 years. Babies’ ages ranged from 2.0 to 12.0 weeks, with a mean of 6.5 ± 1.1 weeks. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. More than half the women (57.3%) were breastfeeding exclusively or supplementing with bottle feeding. Those who had discontinued breastfeeding had done so at a mean of 2.8 ± 1.7 weeks before the visit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample (N = 316)

*Numbers might not add to 316 because of missing data.

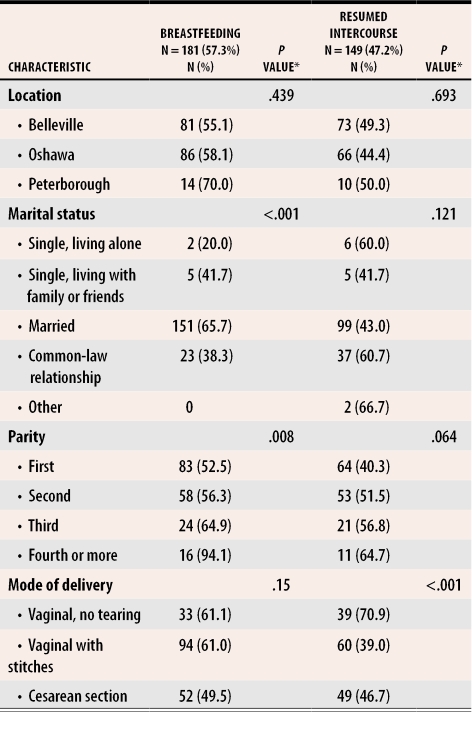

Table 2 shows the relationship between breastfeeding and other variables, including location, marital status, parity, and mode of delivery. Women who said they were breastfeeding exclusively or also supplementing with bottle feeding were considered “currently breastfeeding” for the purpose of this analysis. There was a significant association between breastfeeding and marital status (P < .001), with married women the most likely to breastfeed. Parity was also significant, with a greater likelihood of breastfeeding as parity increased (P = .008). Neither location nor mode of delivery was significantly associated with breastfeeding.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study sample by breastfeeding and resumption of intercourse (N = 316)

*Numbers might not add to 316 because of missing data.

*P value denotes Pearson chi-square (2-sided).

Table 2 also shows the relationship between resumption of intercourse and other variables. Mode of delivery was highly significantly associated with resumption of intercourse (P < .001) in that those with stitches were far less likely to resume intercourse than those without stitches or those who had had cesarean sections.

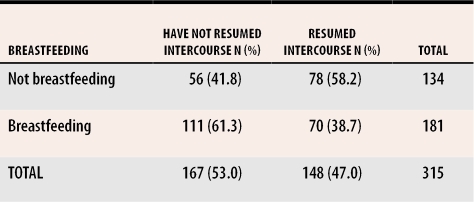

Table 3 depicts the relationship between breastfeeding and resumption of vaginal intercourse. Just over half (167) the women had not resumed vaginal intercourse at the time they completed the questionnaire. There was a statistically significant relationship between breastfeeding and failure to resume intercourse (chi-square 11.8, P = .001). Of the 167 women, 111 (66.5%) were breastfeeding. Among those who had resumed intercourse, 96 (64.9%) had used contraception, and the most common method of contraception was a condom alone.

Table 3. Association between breastfeeding and resumption of vaginal intercourse.

Fisher exact test (2-sided), P = .001.

*Numbers might not add to 316 because of missing data.

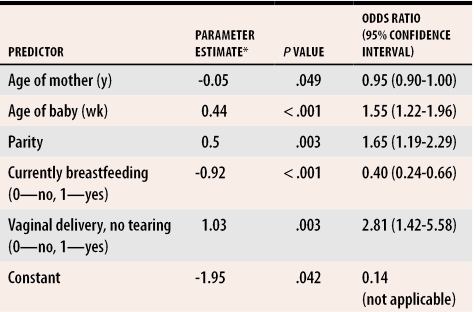

Multivariable logistic regression identified five factors significantly associated with resumption of intercourse (Table 4). Younger women were likely to have resumed intercourse, as were women whose children were older and women who had more children. Women who were currently breastfeeding were less likely to have resumed intercourse (P < .001). Finally, vaginal birth without tearing was strongly associated with resumption of intercourse. Variables that were considered for the model but not retained included marital status and time since delivery.

Table 4.

Factors associated with resumption of intercourse

*Parameter estimate refers to the coefficients of the regression model and indicates the direction of the association. Negative parameter estimates indicate that, as values of the predictor go up, women are less likely to resume intercourse; positive estimates indicate that higher values are associated with women being more likely to resume intercourse.

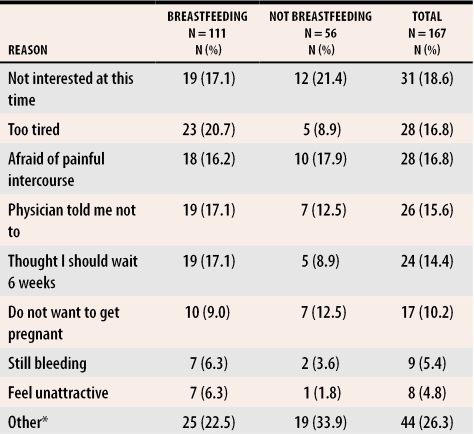

Table 5 shows the most commonly cited reasons for not resuming intercourse, for the entire group and by breastfeeding activity. Of the 167 women who had not resumed intercourse, 161 gave at least one reason. Although the survey instructed women to list the most important reason, 34 gave two reasons, 15 gave three, four gave four, and one gave five. Reported frequencies include all reasons cited, for a total of 215 reasons. There were no significant differences between women who were breastfeeding and women who were not in terms of reasons given for failing to resume intercourse (P = .153).

Table 5. Reasons for not resuming intercourse.

Number of women within each breastfeeding category who gave this reason. Respondents could provide more than one reason.

*Other included no partner; contraceptive issues; vaginal dryness; pain from stitches, episiotomy, or surgery; infection or fear of infection; no time; uncomfortable with dual purpose of breasts; and presence of catheter.

DISCUSSION

There was a strong and statistically significant relationship between breastfeeding and delay in resuming intercourse. Only one third of breastfeeding women had resumed intercourse while almost two thirds (60%) of women who were not breastfeeding had done so. Delayed resumption of intercourse appeared to be the trend even among those who were supplementing breastfeeding with bottles. Those who discontinued breastfeeding early did not delay resumption of intercourse.

Breastfeeding’s negative effect on sexuality might be explained by several factors. Lactating women have elevated prolactin levels that are maintained by breastfeeding. This leads to low gonadotropin levels and consequently low estrogen and progesterone levels due to suppressed ovarian activity. Vaginal dryness is one consequence of this hypo-estrogenized state. Also, Alder et al have measured androgen levels among breastfeeding women and shown significantly lower levels among breastfeeding women who report greatly reduced interest in sex.9

Breastfeeding women might be more at risk of depression, although one study found no evidence that mood changes accounted for the observed adverse effects of breastfeeding on sexuality.13 Others have suggested that women who choose to breastfeed might be different in sexuality and mood before pregnancy compared with women who do not breastfeed. To address this question, Alder and Bancroft did antenatal assessments of mood and sexuality in 91 primiparous women and found no significant association between antenatal status and continuing to breastfeed postnatally. They concluded that any postnatal differences in these measures could be attributed to feeding status.13

The data do not allow us to speculate on when women who had not resumed intercourse would have done so. Other research suggests that the difference in resumption of intercourse between those who breastfeed and those who do not is only about 1 week.8,13 If this is the case, most women in our sample would have resumed intercourse shortly after the survey was completed. Thus, while the difference would have remained statistically significant, it might not be clinically relevant. Both the other studies8,13 relied on retrospective recall, which might have been less accurate than the prospective approach used in this study.

Mode of delivery was also a significant predictor of resumption of intercourse. Women with vaginal deliveries and no tearing were more likely to have resumed intercourse by the time of their first postpartum visit than those who delivered by other modes. This is in contrast to the finding that, at 1 month, those who had delivered by cesarean section were more likely to have resumed intercourse than those who delivered vaginally.8 Both parity and maternal age were also predictors of resumption of intercourse. Higher parity was positively related to resumption of intercourse, but, somewhat paradoxically, younger women were also more likely to have resumed intercourse.

Predictors of breastfeeding behaviour were also examined. When women were in relationships (married or common-law), they were more likely than their single counterparts to be currently breastfeeding. In addition, women of higher parity were more likely to be currently breastfeeding. Vaginal delivery with or without tearing was also a significant predictor of breastfeeding.

Many women experience less sexual expression and satisfaction during pregnancy and after birth, which could be related to mode of delivery, breastfeeding, or other factors not measured in this study. Sexual problems appear to be common after childbirth,4 but few patients discuss them with a health professional.4,5 Patients might benefit from discussing breastfeeding, sexuality, and contraception in the postpartum period with their physicians and should be reassured that changes in sexual expression and satisfaction are to be expected during this unique stage of life.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this research is that it prospectively documents women’s sexuality in the early postpartum period, eliminating the recall bias inevitable when data are collected retrospectively months after the time in question. Glazener collected data as early as 8 weeks post partum,3 but most other studies collected information between 3 and 12 months post partum. Another strength is that marital status was not limited to married as it was in several other studies,5,8,13 but included women living in a variety of circumstances. Finally, the specific reasons women gave for not resuming intercourse might assist clinicians in discussing return to intercourse within the context of postpartum care.

One limitation of this study is that a precise response rate for survey completion could not be calculated due to the nature of the study. Clinic staff thought that the surveys were well received and that most women completed them willingly while waiting for their appointments. Although patients at the clinic were primarily white and middle class, no specific data regarding ethnicity or cultural heritage were collected. These data might have had associations with breastfeeding or resumption of sexual activity. Language level was not an exclusion criterion, but women with a poor understanding of English might have been less likely to participate. Finally, family physicians were not included in the study because, in the three communities studied, most obstetric care was provided by obstetricians. Women who went to follow-up appointments with their family doctors might have been missed, but since initial postpartum visits are normally with the delivering physician, this should not have had a significant effect on the sample.

Conclusion

This prospective survey found that breastfeeding is the most significant predictor of delayed resumption of intercourse, followed by baby’s age, parity, and mode of delivery. Commonly cited reasons for not resuming intercourse included lack of interest, tiredness, fear of pain, and either that their physician told them not to or that they thought they should wait 6 weeks. Patients might benefit from open discussion of breastfeeding, sexuality, and contraception in the postpartum period.

Biography

Drs Rowland, Foxcroft, and Patel are on staff in the Department of Family Medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. Ms Hopman is a Research Facilitator in the Clinical Research Centre at Kingston General Hospital and in the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology at Queen’s University.

References

- 1.Avery MD, Duckett L, Frantzich CR. The experience of sexuality during breastfeeding among primiparous women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2000;45:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(00)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reamy KJ, White SE. Sexuality in the puerperium: a review. Arch Sex Behav. 1987;16:165–186. doi: 10.1007/BF01542069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glazener CM. Sexual function after childbirth: women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, Manyonda I. Women’s sexual health after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grudzinskas JG, Atkinson L. Sexual function during the puerperium. Arch Sex Behav. 1984;13:85–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01542980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falicov CJ. Sexual adjustment during first pregnancy and post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;117:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolor A, DiGrazia PV. Sexual attitudes and behavior patterns during and following pregnancy. Arch Sex Behav. 1976;5:539–551. doi: 10.1007/BF01541218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd JE, Hyde JS, DeLamater JD, Plant EA. Sexuality during pregnancy and the year postpartum. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alder EM, Cook A, Davidson D, West C, Bancroft J. Hormones, mood and sexuality in lactating women. Br J Psychiatry. pp. 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Postpartum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: a retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:881–890. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.113855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udry JR, Deang L. Determinants of coitus after childbirth. J Biosoc Sci. 1993;25:117–125. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000020368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Co; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alder E, Bancroft J. The relationship between breastfeeding persistence, sexuality and mood in postpartum women. Psychol Med. pp. 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Forster C, Abraham S, Taylor A, Llewellyn-Jones D. Psychological and sexual changes after the cessation of breast-feeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:872–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenny JA. Sexuality of pregnant and breastfeeding women. Arch Sex Behav. 1973;2:215–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01541758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]