Abstract

The β-cell ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel controls insulin secretion by linking glucose metabolism to membrane excitability. Loss of KATP channel function due to mutations in ABCC8 or KCNJ11, genes that encode the sulfonylurea receptor 1 or the inward rectifier Kir6.2 subunit of the channel, is a major cause of congenital hyperinsulinism. Here, we report identification of a novel KCNJ11 mutation associated with the disease that renders a missense mutation, F55L, in the Kir6.2 protein. Mutant channels reconstituted in COS cells exhibited wild-type like surface expression level and normal sensitivity to ATP, MgADP, and diazoxide. However, the intrinsic open probability of the mutant channel was greatly reduced, by ~10-fold. This low open probability defect could be reversed by application of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphates or oleoyl CoA to the cytoplasmic face of the channel, indicating that reduced channel response to membrane phospholipids and/or long chain acyl CoAs underlies the low intrinsic open probability in the mutant. Our findings reveal a novel molecular mechanism for loss of KATP channel function and congenital hyperinsulinism, and support the importance of phospholipids and/or long chain acyl CoAs in setting the physiological activity of β-cell KATP channels. The F55L mutation is located in the slide helix of Kir6.2. Several permanent neonatal diabetes-associated mutations found in the same structure have the opposite effect of increasing intrinsic channel open probability. Our results also highlight the critical role of the Kir6.2 slide helix in determining the intrinsic open probability of KATP channels.

Keywords: KATP channel, KCNJ11, inward rectifiers, gating, PIP2, long chain-CoA, congenital hyperinsulinism

Pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels play a key role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by coupling glucose metabolism to β-cell excitability (1–3). Each KATP channel consists of four pore-forming Kir6.2 subunits encoded by KCNJ11 and four regulatory sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) receptors encoded by ABCC8 (4–6). The activity of KATP channels is subject to regulation by intracellular nucleotides ATP and ADP (1,7,8). ATP inhibits channel activity by binding to the Kir6.2 subunit, whereas ADP, in complex with Mg2+, stimulates channel activity by interacting with SUR1. Changes in ATP and ADP concentrations during glucose metabolism are thus linked to KATP channel activity, which in turn controls β-cell membrane potential and insulin secretion. As such, genetic mutations in Kir6.2 or SUR1 that alter channel sensitivity to ATP or MgADP impair the ability of KATP channels to convert metabolic signals to electrical signal, resulting in insulin secretion diseases. In addition to intracellular nucleotides, both long-chain acyl CoAs and membrane phosphoinositides have been shown to stimulate channel activity and reduce channel sensitivity to ATP inhibition by interacting with Kir6.2 (9–17). However, compared to intracellular nucleotides, the role of membrane phosphoinositides or long-chain acyl CoAs in controlling KATP channel activity in physiological and pathological conditions is less clear and still under investigation (8).

Congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) is a disease characterized by persistent insulin secretion despite life-threatening hypoglycemia (3,18–21). Dominant or recessive mutations in ABCC8 or KCNJ11 that reduce or abolish channel activity are the major genetic cause of the disease (3,18–21). Most mutations identified to date reside in the SUR1 subunit (1,3,22,23). Functional studies of a considerable number of missense SUR1 mutations have established loss of channel response to MgADP and impaired expression of functional channels at the cell surface as two major defects (24–27). Relatively few mutations have been reported in the Kir6.2 subunit (1,28); these mutations either introduce a premature stop codon that results in truncated nonfunctional Kir6.2 protein or introduce missense mutations that cause rapid degradation of the protein (28,29). Here, we report the identification and functional characterization of a dominant CHI-associated Kir6.2 missense mutation F55L. We show that this mutation greatly reduces the open probability of KATP channels in intact cells without affecting channel expression. The low channel activity is likely due to reduced channel response to membrane phosphoinositides and/or long-chain acyl CoAs, as application of exogenous PIP2 or oleoyl CoA restores channel activity to that seen in wild-type (WT) channels. Our finding identifies impaired KATP channel response to phospholipids and/or long-chain acyl CoAs as a novel mechanism underlying congenital hyperinsulinism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical and genetic analyses

Tests of acute insulin responses (AIR) to calcium (2 mg/kg), leucine (15 mg/kg), glucose (0.5 gm/kg), and tolbutamide (25 mg/kg) sequentially infused intravenously at intervals of one hour were carried out as previously described (27). Peripheral blood was obtained for isolation of genomic DNA from the proband, a male infant, and his father. Direct sequencing of DNA from the patient and family members was done as previously described (27).

Molecular biology

Rat Kir6.2 cDNA is in pCDNAI/Amp vector (a generous gift from Dr. Carol A. Vandenberg) and SUR1 in pECE. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Strategene) and the mutation confirmed by sequencing. Mutant clones from two independent PCR reactions were analyzed to avoid false results caused by undesired mutations introduced by PCR.

86Rb+ efflux assay

COSm6 cells were plated onto 35 mm culture dishes and transfected with wild-type SUR1 and control or mutant rat Kir6.2 cDNA using FuGene. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in culture medium containing 86RbCl (1μCi/ml) 2 days after transfection. Before measurement of 86Rb+ efflux, cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in Krebs-Ringer solution with metabolic inhibitors (2.5 μg/ml oligomycin and 1 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose). At selected time points, the solution was aspirated from the cells, and replaced with fresh solution. At the end of a 40 min period, cells were lysed. The 86Rb+ in the aspirated solution and the cell lysate was counted. The percentage efflux at each time point was calculated as the cumulative counts in the aspirated solution divided by the total counts from the solutions and the cell lysates (25).

Western blotting and chemiluminescence assay

Cell surface expression level of the mutant channel was assessed by Western blot and by a quantitative chemiluminescence assay using a SUR1 that was tagged with a FLAG-epitope (DYKDDDDK) at the N-terminus (fSUR1), as described previously (30). COSm6 cells grown in 35 mm dishes were transfected with 0.4 μg rat Kir6.2 and 0.6 μg fSUR1 and lysed 48–72 hours post-transfection in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0/5 mM EDTA/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40 (IGAPEL) with CompleteTR protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins in the cell lysate were separated by SDS/PAGE (7.5% for SUR1 and 12% for Kir6.2), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by incubation with appropriate primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Femto; Pierce, Rockford, IL). The primary antibodies used are: M2 mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody for fSUR1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Kir6.2 for Kir6.2 (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For chemiluminescence assay, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Fixed cells were preblocked in PBS+0.1% BSA for 30 min, incubated in M2 anti-FLAG antibody (10 μg/ml) for an hour, washed 4×30 min in PBS+0.1% BSA, incubated in HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Jackson, 1:1000 dilution) for 20 min, and washed again 4x30 min in PBS+0.1% BSA, all at room temperature. Chemiluminescence of each dish was quantified in a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs) following 15 sec incubation in Power Signal Elisa luminol solution (Pierce). All steps after fixation were carried out at room temperature.

Electrophysiology

Patch-clamp recordings were performed in the inside-out configuration as previously described (30). Briefly, COSm6 cells were tranfected with cDNA encoding WT or mutant channel proteins, as well as cDNA for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to help identify positively transfected cells. Patch-clamp recordings were made 36–72 hours post-transfection. Micropipettes were pulled from non-heparinized Kimble glass (Fisher Scientific) with resistance typically ~1–2 MΩ. The bath (intracellular) and pipette (extracellular) solution (K-INT) had the following composition: 140 mM KCl, 10 mM K-HEPES, 1 mM K-EGTA, pH 7.3. ATP and ADP were added as the potassium salt. For measuring ATP4− sensitivity, 1 mM EDTA was included in K-INT to prevent channel rundown (31). All currents were measured at a membrane potential of −50 mV (pipette voltage = +50 mV) and inward currents shown as upward deflections. Data were analyzed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instrument). Offline analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel programs. The MgADP or diazoxide response was calculated as the current in a K-INT solution containing either 0.1 mM ATP and 0.5 mM ADP or 0.1 mM ATP and 0.3 mM diazoxide (both with 1 mM free Mg2+), relative to that in plain K-INT solution.

Data Analysis

ATP dose response curve fitting was performed with Origin 6.1. Channel intrinsic Po was estimated from stationary fluctuation analysis of short recordings (~ 1 second) of macroscopic currents in KINT/EDTA solution or KINT/EDTA plus 5 mM ATP (32–34). Currents were filtered at 1 kHz. Mean current (I) and variance (σ2) in the absence of ATP were obtained by subtraction of the mean current and variance in 5 mM ATP. Single channel current (i) was assumed to be −3.6 pA at −50 mV (corresponding to single channel conductance of 72 pS). Po was then calculated using the following equation: Po = 1 − (σ2/[i*I]). Statistical analysis was performed using independent two-population two-tailed Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Patient history and identification of the F55L missense mutation in Kir6.2

The proband was a male infant diagnosed with persistent hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinism at 12 hours of age (14 μU/ml with a blood glucose level of 31 mg/dL; 13 μU/ml with blood glucose of 24 mg/dL; normal < 3 μU/ml). Tests of acute insulin responses to secretogogues were performed in the proband and his father and results compared to hyperinsulinism patients with recessive ABCC8 null mutations (3992-9G→A and ΔF1388) and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) mutations and normal adult controls (35). The proband showed a pattern of responses similar to those seen in patients with recessive ABCC8 mutations, an abnormal positive insulin response to calcium stimulation, as well as possibly diminished responses to glucose and tolbutamide (Table I). The father of the proband had mildly abnormal acute insulin responses, including abnormally increased insulin responses to calcium and leucine, and a lower response to tolbutamide than to glucose stimulation. This pattern of insulin responses resembles that seen in children with hyperinsulinism due to recessive ABCC8 and KCNJ11 mutations which retain partial channel activity (35). Subsequent genetic testing revealed that the proband and the father shared a 165C→A mutation in the KCNJ11, resulting in a missense mutation, F55L, in the Kir6.2 subunit of the KATP channel. Of note, although the father showed mildly abnormal acute insulin responses as well as evidence of protein-sensitive hypoglycemia (blood glucose nadir of 63 mg/dL at 60 min following ingestion of oral protein; normals > 70 mg/dL), he demonstrated normal fasting blood glucose (84 mg/dL after 12 hr fast). The more severe hypoglycemia seen in the proband, at least in the newborn period, is likely attributed in part to perinatal stress, as has been reported previously (36,37).

Table I.

In vivo islet phenotype (Acute Insulin Responses)

| Acute insulin responses to secretogogues in proband with F55L mutation of KCNJ11 (μU/mL, mean ± SD). | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Leucine | Glucose | Tolbutamide | |

| Proband (17 days old) | 36 | 5 | 25 | 16 |

| Father of proband | 9 | 13 | 114 | 44 |

| Hyperinsulinism due to recessive ABCC8 (SUR1) mutationsa (n=7) | 28 ± 16 | 5 ± 8 | 12 ± 9 | 4 ± 6 |

| Hyperinsulinism due to dominant GLUD1 mutations (n=7) | 2.3 ± 5.4 | 42 ± 27 | 120 ± 52 | 94 ± 65 |

| Normal adult controls (n=6) | 3 ± 4 | 1.4 ± 2.8 | 56 ± 26 | 48 ± 32 |

Common Ashkenazi Jewish mutation: 3992-9 G→A or ΔF1388 (55).

Treatment with diazoxide at 15 mg/kg/day rapidly improved the hypoglycemia in the proband. Within 4 days, he was able to fast 12 hr without hypoglycemia. Periodic reassessments up to 4 years of age showed that, while on treatment with a low dose of diazoxide at 4 mg/kg/day, the proband was able to fast successfully for 12–15 hours without hypoglycemia and did not develop hypoglycemia in response to an oral protein tolerance test (1 gm/kg).

The F55L mutation reduces open probability of KATP channels

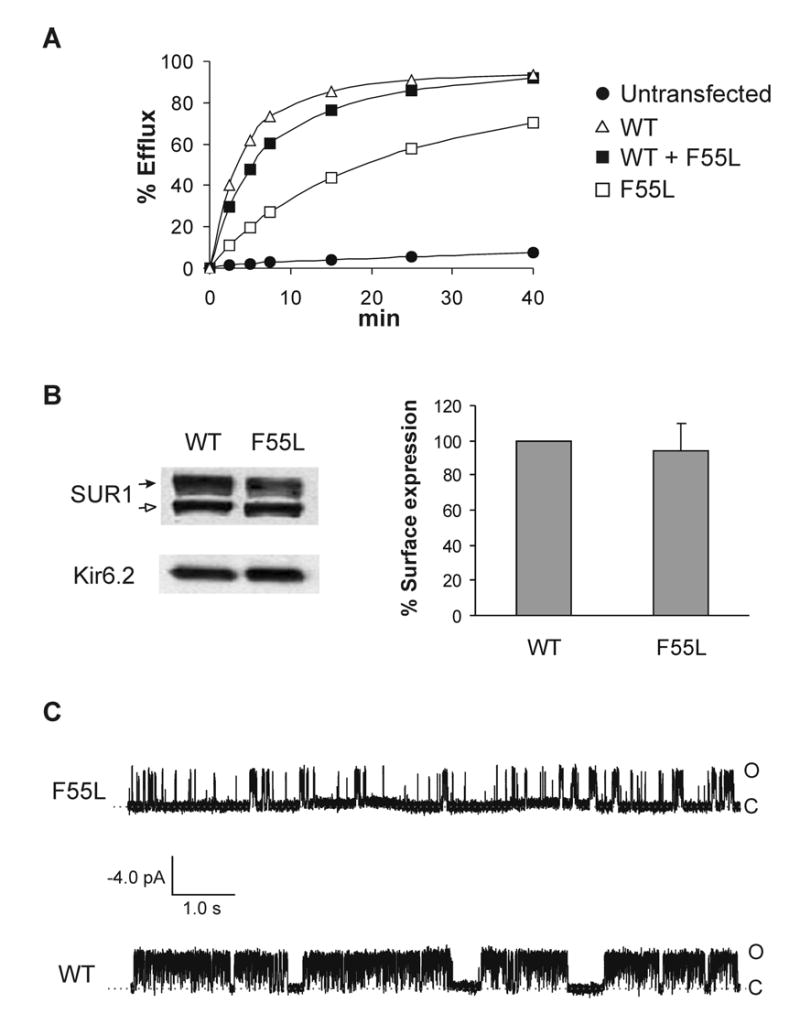

To investigate how the F55L mutation in Kir6.2 affects channel function, we reconstituted the mutant channels in COS cells by co-expression of F55L-Kir6.2 and SUR1. To first confirm reduction or loss of channel activity in intact cells during glucose deprivation, as one would predict based on the disease phenotype, we performed 86Rb+ efflux assays to assess channel activity in response to metabolic poisoning. As shown in Fig.1A, homomeric mutant channels are much less active upon metabolic inhibition compared to WT channels. Because the F55L mutation is heterozygous in the patient, we simulated the heterozygous state by co-expressing WT and mutant Kir6.2 at 1:1 cDNA molar ratio with SUR1 (referred to as hetF55L). The hetF55L channels, although are much more active than homomeric F55L mutant channels (referred to as homF55L), are still less active than WT channels. These results demonstrate the causal role of the Kir6.2 F55L mutation in congenital hyperinsulinism.

Fig. 1. Analyses of mutant channel activity, expression and single channel properties.

(A) Reduced activity of mutant KATP channels reconstituted in COSm6 cells in response to metabolic inhibition. COSm6 cells expressing wild-type (WT), homF55L (F55L), or hetF55L (WT+F55L) channels were subjected to 86Rb+ efflux assays as described previously (25). Metabolic inhibition activated WT channels with 86Rb+ efflux reaching >90% in a 40-min period. By comparison, WT+F55L channels were less active, and F55L still less active. In the absence of metabolic inhibition, both WT and mutant channels exhibited background efflux indistinguishable from untransfected cells (not shown). (B) Left, Western blots of fSUR1 (upper panel) and Kir6.2 (lower panel) in COSm6 cells coexpressing fSUR1 and WT Kir6.2 or fSUR1 and F55L Kir6.2. The complex-glycosylated fSUR1 is indicated by the solid arrow and the core-glycosylated form the open arrow. Comparable expression of both fSUR1 and Kir6.2 was observed in cells expressing WT or mutant KATP channels. Right, cell surface expression quantified using chemiluminescence assays. Expression of the mutant is normalized to that of WT. Data represent mean ± S.E. of 3 independent experiments (dishes in duplicates or triplicates for each experiment). There is no statistically significant difference between the expression of WT and the mutant (p > 0.1). (C) Single-channel recordings of WT and the F55L mutant. O: open; C: closed. Recordings were made at +50 mV pipette potential with symmetrical K-INT/EDTA solution on both sides of the membrane patch. Inward currents are shown as upward deflection.

The reduced activity of the mutant channel upon metabolic inhibition could be due to reduced surface expression or altered gating properties (3). To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the level of surface expression of mutant channels to that of WT channels. Western blots showed that the steady-state mutant Kir6.2 protein level is similar to WT Kir6.2 (Fig.1B, left). Moreover, fSUR1 co-expressed with the F55L mutant Kir6.2 exhibits core-glycosylated as well as complex-glycosylated forms comparable to that observed in fSUR1 co-expressed with WT Kir6.2 (Fig.1B, left), indicating the mutation does not affect surface expression of the channel. Quantification of surface expression by chemiluminescence assays further corroborated the conclusion that the F55L mutation does not affect channel expression (Fig.1B, right).

The above results suggest that the reduced activity seen in the mutant is likely due to altered gating regulation. We therefore carried out detailed electrophysiological analysis using the inside-out patch-clamp recording technique. Upon patch excision into ATP-free solution, WT channels gave averaged currents of ~2 nA at −50 mV with symmetrical potassium concentrations on both sides of the membrane. By contrast, the averaged current amplitude from the F55L mutant channels was only ~0.2 nA. To test whether the reduction in current amplitude results from reduced single channel conductance or channel open probability, we performed single channel recording of the mutant. The F55L mutant exhibited single channel conductance (70.4 ± 1.6 pS) comparable to that of WT channel (68.0 ± 3.1 pS). However, the channel open probability appears greatly reduced (Fig.1C). These results show that the mutation reduces the ATP-independent open probability (referred to as the intrinsic open probability in this study) of KATP channels.

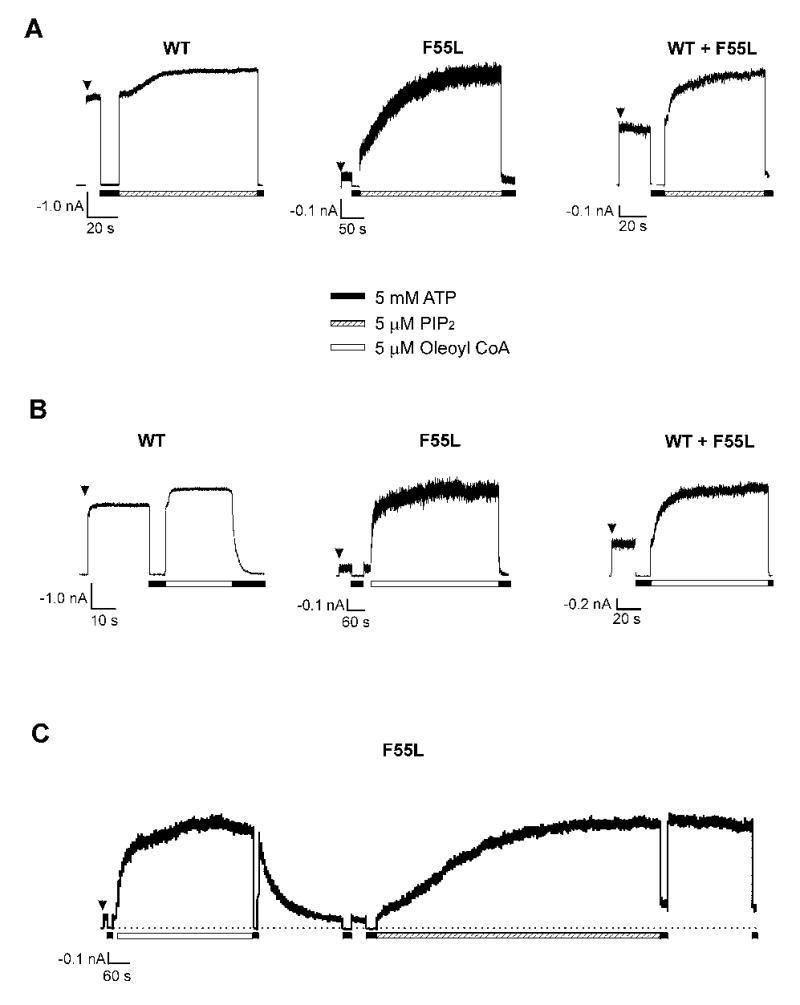

Effects of PIP2 and oleoyl-CoA on the F55L mutant channel

Membrane phosphoinositides, in particular PIP2, are known to affect the open probability of KATP channels (15,17,38). Recently, we reported that expression of Kir6.2 constructs with deliberate mutations that abolish channel sensitivity to PIP2 (R176A, R177A, R206A) in the insulin secreting cell INS-1 results in phenotypes mimicking those seen in congenital hyperinsulinism. These include reduced KATP channel activity, depolarized membrane potential, and excessive insulin secretion, at basal glucose concentration. We therefore hypothesize that the reduced channel open probability observed in the F55L mutant could be due to attenuated channel response to PIP2. Supporting this hypothesis, we found that in inside-out patch-clamp recordings application of exogenous PIP2 (5 μM) to the cytoplasmic face of the membrane markedly increased the current amplitude of the F55L mutant channels (Fig.2A). The fold increase in current amplitude upon PIP2 stimulation for WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels are 1.27 ± 0.08, 2.27 ± 0.34, and 10.02 ± 2.39, respectively (Table II). Based on the fold increase in current amplitude, we expect the Po of WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels to be ~0.78, 0.44, and 0.1, respectively, assuming the maximal Po after PIP2 stimulation is near 1 for all channels. Using noise analysis (33,34) we estimated the Po of WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels before and after PIP2 stimulation. As shown in Table I, the Po for WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels prior to PIP2 application was 0.81 ± 0.02, 0.66 ± 0.04, and 0.11 ± 0.01, respectively. After PIP2 stimulation, the Po for WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels increased to 0.94 ± 0.01, 0.89 ± 0.02, and 0.72 ± 0.04. These numbers are in general agreement with the trend expected based on macroscopic current amplitude increase. However, note that the Po estimated by the noise analysis is likely higher because underestimation of the noise due to filtering (32–34,39). Also, the maximal Po estimated by noise analysis after PIP2 stimulation for homF55L mutant channels is 0.72, significantly lower than 1 (p<0.01). Therefore the intrinsic Po of the homF55L mutant channel is likely below 0.1 (based on a ~10-fold increase in macroscopic currents after PIP2 stimulation and the estimated maximal Po of 0.72).

Fig. 2. Reduced sensitivity of F55L mutant channels to PIP2 and oleoyl CoA.

(A) Representative inside-out patch-clamp recordings from cells expressing wild-type (WT; n = 6), homF55L (F55L; n = 10), or hetF55L (WT + F55L; n = 3). Note the very low activity of the homomeric F55L mutant channel upon patch excision and the large increase in current amplitude upon exposure to PIP2. (B) Same as (A) except that channels were exposed to 5μM oleoyl CoA (n = 7, 15, and 5 for WT, WT+F55L, and F55L, respectively). (C) Direct comparison of F55L mutant channel response to oleoyl CoA and PIP2 in the same patch (an example from a total of four such recordings). Note the effect of oleoyl CoA could be easily washed out whereas the effect of PIP2 was irreversible. Also, some patches showed obvious reduction in sensitivity to inhibition by 5 mM ATP, as previously reported (15,17). All recordings were made at +50 mV pipette potential with symmetrical K-INT/EDTA solution on both sides of the membrane patch. Inward currents are shown as upward deflection.

Table II.

Effects of PIP2 and Oleoyl CoA on channel activity

| Channel | Intrinsic Poa | Poa after 5 μM PIP2 | Poa after 5 μM Oleoyl CoA | Current increase after 5 μM PIP2 (fold) | Current increase after 5 μM Oleoyl CoA (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.81 ± 0.02 (n = 13) | 0.94 ± 0.01 (n = 6) | 0.94 ± 0.01 (n = 7) | 1.27 ± 0.08 (n = 6) | 1.18 ± 0.03 (n = 7) |

| F55L | 0.11 ± 0.01 (n = 25) | 0.72 ± 0.04 (n = 10) | 0.66 ± 0.05 (n = 15) | 10.02 ± 2.39 (n = 10) | 13.12 ± 2.48 (n = 15) |

| WT + F55L | 0.66 ± 0.04 (n = 8) | 0.89 ± 0.02 (n = 3) | 0.88 ± 0.04 (n = 5) | 2.27 ± 0.34 (n = 3) | 2.01 ± 0.22 (n = 5) |

Values derived from noise analysis.

Long-chain acyl CoAs, like PIP2, stimulate KATP channel activity by interacting with Kir6.2 and have been proposed to play a role in modulating channel activity in β-cells (9,10,14,40). At 5 μM, oleoyl CoA stimulated F55L channel activity to a similar extent (13.12 ± 2.18 fold increase) as 5 μM PIP2 (Fig.2B, Table I). However, in a given patch, the time course of stimulation is faster with oleoyl CoA than with PIP2 (Fig.2C). In addition, unlike the effect of PIP2, the effect of oleoyl CoA is readily reversible (Fig.2C). Taken together, these results are consistent with the notion that the F55L mutation renders the channel less responsive to endogenous membrane phosphoinositides and/or long-chain acyl CoAs, leading to lower channel open probability, thereby persistent membrane depolarization and hyperinsulinism.

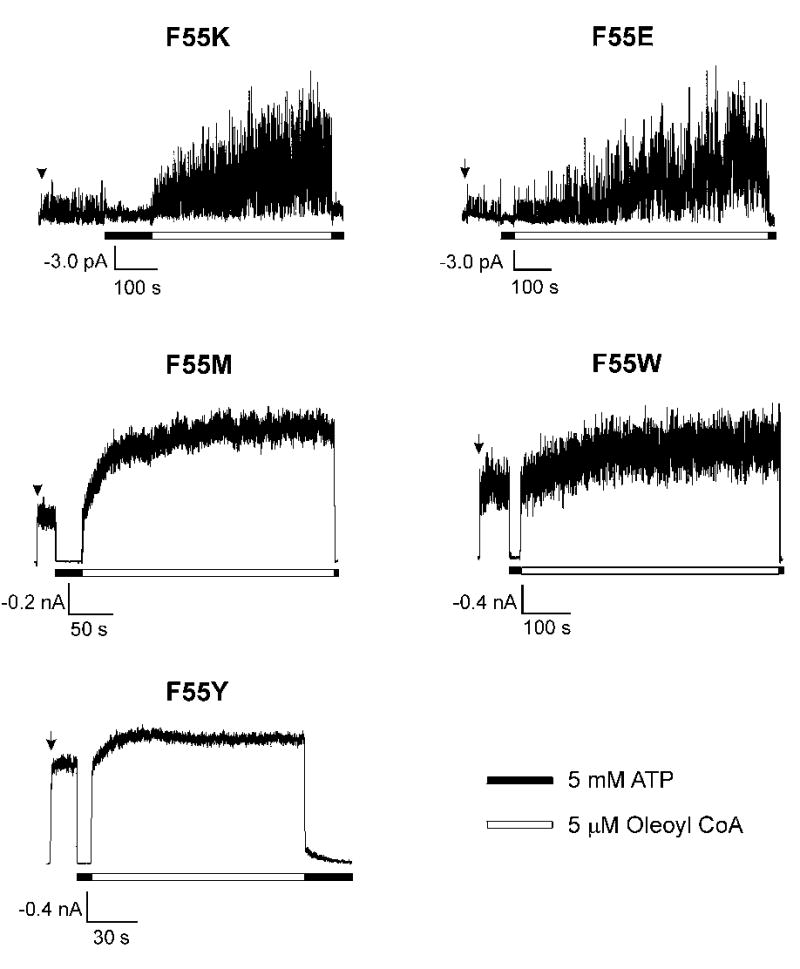

Reduced channel sensitivity to phosphoinositides/long-chain acyl CoAs could result from reduced binding to these ligands or impaired gating movements following ligand binding. To gain further insight into the mechanism, we substituted F55 with additional amino acids with distinct biophysical properties. We reasoned that if the residue is directly involved in lipid binding, mutation to positively charged residue should increase channel activity whereas mutation to negatively charged residue should decrease channel activity, as shown previously for other PIP2/CoA binding residues (15,40–42). Mutation of F55 to either positively charged lysine or negatively charged glutamate yielded channels with very low activity, which increased markedly upon exposure to oleoyl CoA (Fig.3) or PIP2 (not shown). The current increase after 5 μM oleoyl CoA stimulation was > 20-folds for both F55E and F55K (n = 3; Fig.3). In comparison, mutation of F55 to hydrophobic methionine yielded channels whose intrinsic open probabilities are lower than WT but higher than F55L, with the fold-increase in macroscopic current upon stimulation by 5μM oleoyl CoA for F55M being 3.11 ± 0.18 (n =5). By contrast, introduction of aromatic amino acids tryptophan or tyrosine at this position had very mild or no effect on channel activity. The fold-increase in macroscopic current after oleoyl CoA stimulation for F55W and F55Y are 1.65 ± 0.01 (n = 3) and 1.14 ± 0.06 (n = 4), respectively. These results suggest that the aromatic side-chain rather than charge at this amino acid position is important for the slide helix structure and function of the channel (see Discussion).

Fig. 3. Mutation of Kir6.2 residue F55 to other amino acids: effects on channel response to oleoyl-CoA.

Representative inside-out patch-clamp recordings from cells coexpressing SUR1 and Kir6.2 with phenylalanine at position 55 mutated to lysine (F55K; n = 3), glutamate (F55E; n = 3), methionine (F55M; n = 4), tryptophan (F55W; n = 3), or tyrosine (F55Y; n = 4). Recording conditions were as described in Fig.2. Response of the various mutant channels to PIP2 was similar to their response to oleoyl CoA (not shown).

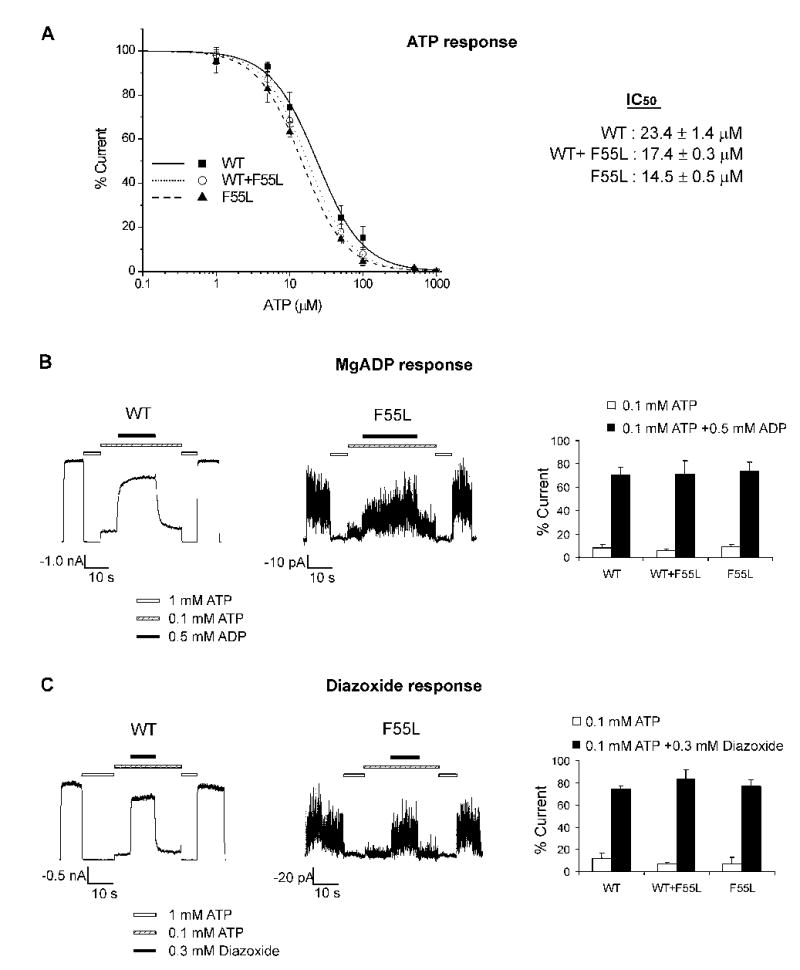

Nucleotide sensitivity and diazoxide response of F55L mutant channels

To test whether the F55L mutation also affects channel sensitivity to intracellular nucleotides, we examined mutant channel response to ATP and MgADP. ATP-dose response curves were constructed by exposing channels to various concentrations of ATP4− in K-INT plus 1 mM EDTA solution (see Materials and Methods); EDTA was used as it effectively prevents channel rundown, allowing for more accurate measurement of ATP sensitivity (31). The half maximal inhibition concentration (IC50) for WT, hetF55L, and homF55L channels are 23.4 ± 1.4, 17.4 ± 0.3, and 14.5 ± 0.5 μM, respectively (Fig.4A); the IC50 of homF55L channels is slightly although significantly lower than that of WT channels (p < 0.01). Next, the response of the F55L mutant channel to MgADP stimulation was examined. In these experiments, we compared the current in 0.1 mM ATP with that in 0.1 mM ATP and 0.5 mM ADP (free Mg2+ concentration ~1 mM). In WT channels, 0.5 mM ADP in the presence of Mg2+ antagonized the inhibitory effect of 0.1 mM ATP and stimulated channel activity (Fig.4B). This stimulatory effect was fully retained in the F55L mutant channel (Fig.4B), indicating the mutation does not disrupt the coupling between SUR1 and Kir6.2. As described above, the patient carrying the F55L mutation responded to treatment by the potassium channel opener diazoxide. Because the mutation is heterozygous, the diazoxide response could simply be conferred by the WT allele. We therefore examined whether the F55L mutation in Kir6.2 affects diazoxide sensitivity. Under the same experimental paradigm, the response of homF55L mutant channel to diazoxide stimulation was comparable to that seen in WT channels (Fig.4C). Thus, the F55L mutation does not affect the channel’s ability to respond to diazoxide. It is worth noting however, that while both MgADP and diazoxide stimulated mutant channel activity, the current amplitude at maximal stimulation even after prolonged exposure (> 10 min; not shown) did not exceed the initial current observed in K-INT solution (Fig.4B, C). These results indicate the nucleotide stimulatory effect of SUR1 cannot overcome the low intrinsic open probability defect caused by the F55L mutation in Kir6.2.

Fig. 4. Analyses of response of the F55L mutant channel to ATP, MgADP, and diazoxide.

(A) ATP dose response curve of wild-type (WT), hetF55L (WT+F55L), and homF55L (F55L) channels. Channels in inside-out patches were exposed to varying concentrations of ATP in KINT/EDTA solution. Channel activity was normalized to that seen in the absence of ATP. The curves were fit by the Hill equation (Irel = 1/(1+([ATP]/IC50)H); Irel = current in [ATP]/current in zero ATP; H = Hill coefficient; IC50 = [ATP] causing half-maximal inhibition) to averaged data. The Hill coefficients are 1.37, 1.45, and 1.45 for WT, WT+F55L, and F55L, respectively. Each data point is the average of 5–7 patches. (B) Channel response to MgADP. Representative inside-out patch clamp recordings of WT or homomeric F55L channels are shown (left and middle; from a total of 6 recordings for each channel type). Patches were exposed to 1 mM ATP, 0.1 mM ATP, or 0.1 mM ATP plus 0.5 mM ADP, with free Mg2+ concentration at ~1 mM in all solutions. Currents in 0.1 mM ATP or 0.1 mM ATP plus 0.5 mM ADP were normalized to currents in nucleotide-free solution for WT (n = 6), WT+F55L (n = 5), and F55L channels (n = 6). The bar is the mean ± S.E. (C) Same as (B) except that channels were tested for their response to 0.3 mM diazoxide. Each bar is the mean ± S.E. (n = 7, 4, and 4 for WT, WT+F55L, and F55L, respectively). There is no statistically significant difference between channel responses to MgADP or diazoxide (p > 0.1).

DISCUSSION

Since the linkage between KATP channel mutations and congenital hyperinsulinism was established a decade ago, much effort has been devoted to understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which mutations alter channel function, as this information is necessary for developing pharmacological strategies towards disease treatment (1,3,19,43). Studies thus far, mostly from SUR1 mutations, have shown loss of surface channel expression due to defects in channel biogenesis or trafficking and loss of channel sensitivity to MgADP as two major mechanisms leading to channel dysfunction (3). In this work, we have identified a KCNJ11 mutation 165C→A that results in a missense mutation, F55L, in Kir6.2. Functional analysis of the mutant channel revealed a novel defect. Unlike previously reported disease mutations, the missense F55L mutation in Kir6.2 does not affect channel expression nor channel response to MgADP. Instead, it renders the channel much less active by decreasing the intrinsic channel open probability, by at least 10-fold. The reduced channel open probability is consistent with the mutation playing a causal role in the disease.

Mechanisms underlying the reduced open probability of F55L mutant channels

In the absence of nucleotides, WT KATP channels have reported open probability of ~0.5–0.8 (38,44–46). The level of phosphoinositides such as PIP2 in the plasma membrane has been positively correlated with the intrinsic open probability of KATP channels (15,17,38). The fact that the F55L mutant channel activity is markedly increased by application of exogenous PIP2 supports the notion that reduced channel sensitivity to PIP2 accounts for the reduced open probability seen in the mutant. Currently available experimental approaches do not allow for definitive tests of whether the mutation reduces channel sensitivity to PIP2 by directly affecting binding, indirectly affecting the gating steps following PIP2 binding, or both. Several positively charged residues in the cytoplasmic domain of Kir6.2 have been proposed as PIP2 binding residues, including R54, which is immediately adjacent to F55 (15,39,41,42). Deliberate mutation of R54 to neutral alanine or glutamine or to negatively charged glutamate results in channels with reduced PIP2 response and low open probability similar to the F55L mutant (39,41), whereas mutation to positively charged lysine results in a channel with WT-like phenotype (41). These observations have led to the proposal that R54 may be directly involved in PIP2 binding (41). F55 is the first amino acid in the predicted amphipathic “slide helix” that runs parallel to the lipid bilayer; the slide helix has been proposed to move laterally along the membrane during channel gating (47). Given our results that substitution of F55 by either lysine or glutamate both greatly reduced channel open probability whereas mutation of F55 to tryptophan or tyrosine, two other amino acids also containing an aromatic side chain, gave rise to channels resembling WT, F55 is unlikely a PIP2/CoA-binding residue. Rather, our data suggest that the reduced sensitivity to PIP2/CoA seen in the F55L mutant may be due to impaired transduction steps following PIP2 binding. The leucine mutation may disrupt the amphipathic helical structure and interfere with the ability of the helix to move along the membrane during gating. Alternatively, F55L may interfere with PIP2/CoA binding indirectly by preventing other residues from interacting with PIP2/CoA.

In addition to reduced PIP2 sensitivity and reduced open probability, a slightly increased ATP sensitivity was also observed in the F55L mutant. We do not believe this increased ATP sensitivity is a result of increased ATP binding affinity but a consequence of allosteric effect. This is consistent with previous studies showing that channel open probability is negatively correlated with ATP sensitivity (38). The increased ATP sensitivity is not likely to contribute to the disease since at physiological concentrations of ATP (mM range) most WT channels are already closed (48). Some mutations in Kir6.2 that reduce channel sensitivity to PIP2, such as R176C and R177C, have been reported to cause uncoupling between SUR1 and Kir6.2 and abolish channel response to MgADP (49). This is not the case for F55L, as the channel exhibits normal response to both MgADP and diazoxide. Since both R176C and R177C are believed to directly reduce PIP2 binding affinity, the distinction between these two mutants and F55L is consistent with our above suggestion that F55L reduces channel sensitivity to PIP2 via a different mechanism.

The reduced intrinsic channel open probability caused by the F55L mutation in Kir6.2 is in direct contrast to the increased intrinsic channel open probability reported in a group of neonatal diabetes-causing Kir6.2 mutations including V59G which is also located in the slide helix of Kir6.2 (50,51). The V59G mutation results in channels with very high intrinsic open probability that cannot be reversed by prolonged incubation with the PIP2-binding polycation neomycin, suggesting that the mutant channel is locked in an open state (50). These studies show that disruption of the slide helix structure by mutations can lead to either gain or loss of channel open probability, highlighting the critical role of the slide helix in KATP channel gating.

Membrane phosphoinositides and long-chain CoAs in KATP channel regulation

The gating effects of membrane phosphoinositides and long-chain CoAs on KATP channels in isolated membranes have been well documented (9–17). Structure-functional studies indicate that modulation of channel activity by the two classes of lipid molecules involve the same set of Kir6.2 residues (9–11,40). Our results that both PIP2 and oleoyl-CoA rescue the Po defect of the F55L mutant channel are consistent with this notion. However, because phosphoinsotides and long-chain CoAs appear to share the same gating mechanism, it has been difficult to study the relative role of the two classes of lipids in determining channel activity in physiological or pathological conditions (8,52). Recently, we reported that manipulations of channel-PIP2 interactions in the insulin-secreting cell line INS-1 have profound effects on channel activity and the coupling between glucose and insulin secretion (53). A Kir6.2 polymorphism, E23K/I337V, that has been implicated in type II diabetes was recently shown to increase channel sensitivity to long-chain CoAs (12,16,54). Our study presented here demonstrates that a naturally occurring mutation in human that reduces channel response to PIP2/CoA results in congenital hyperinsulinism. Together, these studies are consistent with both classes of lipid molecules playing a role in controlling channel activity. They raise the possibility that membrane phosphoinositides and long chain CoAs could serve as potential pharmacological targets for treating insulin secretion disorders caused by KATP channel mutations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Carol A. Vandenberg for the rat Kir6.2 clone and Jillene Casey from the Shyng lab for technical assistance. We are grateful to the patients, the General Clinical Research Center staff and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia nurses without whom this work would not have been possible. This work was supported by NIH Grant R01DK57699 to S.-L. Shyng, R01DK56268 and 5-MO1-RR-000240 to C. A. Stanley, and a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association to Y.-W. Lin.

References

- 1.Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:101–135. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashcroft FM, Gribble FM. Diabetologia. 1999;42:903–919. doi: 10.1007/s001250051247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huopio H, Shyng SL, Otonkoski T, Nichols CG. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E207–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00047.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement J P t, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Neuron. 1997;18:827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Seino S. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shyng S, Nichols CG. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:655–664. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashcroft FM. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:97–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarasov A, Dusonchet J, Ashcroft F. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S113–122. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gribble FM, Proks P, Corkey BE, Ashcroft FM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26383–26387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branstrom R, Leibiger IB, Leibiger B, Corkey BE, Berggren PO, Larsson O. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31395–31400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulze D, Rapedius M, Krauter T, Baukrowitz T. J Physiol. 2003;552:357–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedel MJ, Boora P, Steckley D, de Vries G, Light PE. Diabetes. 2003;52:2630–2635. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulze, D., Rapedius, M., Krauter, T., and Baukrowitz, T. (2003) J Physiol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Branstrom R, Aspinwall CA, Valimaki S, Ostensson CG, Tibell A, Eckhard M, Brandhorst H, Corkey BE, Berggren PO, Larsson O. Diabetologia. 2004;47:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. Science. 1998;282:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riedel MJ, Light PE. Diabetes. 2005;54:2070–2079. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shyng SL, Nichols CG. Science. 1998;282:1138–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Nakazaki M. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:47–68. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunne MJ, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:239–275. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser B. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:150–163. doi: 10.1053/sp.2000.6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanley CA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4857–4859. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma N, Crane A, Gonzalez G, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L. Kidney Int. 2000;57:803–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Wilson BA, Shyng SL, Nichols CG, Stanley CA, Thornton PS, Permutt MA. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo M, Trapp S, Tanizawa Y, Kioka N, Amachi T, Oka Y, Ashcroft FM, Ueda K. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41184–41191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shyng SL, Ferrigni T, Shepard JB, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Permutt MA, Nichols CG. Diabetes. 1998;47:1145–1151. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.7.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols CG, Shyng SL, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Clement J P t, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Permutt MA, Bryan J. Science. 1996;272:1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magge SN, Shyng SL, MacMullen C, Steinkrauss L, Ganguly A, Katz LE, Stanley CA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4450–4456. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nestorowicz A, Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Schoor KP, Wilson BA, Glaser B, Landau H, Stanley CA, Thornton PS, Seino S, Permutt MA. Diabetes. 1997;46:1743–1748. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crane A, Aguilar-Bryan L. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9080–9090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taschenberger G, Mougey A, Shen S, Lester LB, LaFranchi S, Shyng SL. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:17139–17146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin YW, Jia T, Weinsoft AM, Shyng SL. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:225–237. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neher E, Stevens CF. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1977;6:345–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.06.060177.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigworth FJ. J Physiol. 1980;307:97–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shyng S, Ferrigni T, Nichols CG. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:141–153. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henwood MJ, Kelly A, Macmullen C, Bhatia P, Ganguly A, Thornton PS, Stanley CA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:789–794. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins JE, Leonard JV, Teale D, Marks V, Williams DM, Kennedy CR, Hall MA. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1118–1120. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.10.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins JE, Leonard JV. Lancet. 1984;2:311–313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enkvetchakul D, Loussouarn G, Makhina E, Shyng SL, Nichols CG. Biophys J. 2000;78:2334–2348. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76779-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cukras CA, Jeliazkova I, Nichols CG. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:437–446. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manning Fox JE, Nichols CG, Light PE. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:679–686. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulze D, Krauter T, Fritzenschaft H, Soom M, Baukrowitz T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10500–10505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shyng SL, Cukras CA, Harwood J, Nichols CG. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:599–608. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas PM, Cote GJ, Wohllk N, Haddad B, Mathew PM, Rabl W, Aguilar-Bryan L, Gagel RF, Bryan J. Science. 1995;268:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.7716548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drain P, Li L, Wang J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13953–13958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babenko AP, Gonzalez G, Bryan J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11587–11592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Proks P, Capener CE, Jones P, Ashcroft FM. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:341–353. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Antcliff JF, Rahman T, Lowe ED, Zimmer J, Cuthbertson J, Ashcroft FM, Ezaki T, Doyle DA. Science. 2003;300:1922–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.1085028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cook DL, Satin LS, Ashford ML, Hales CN. Diabetes. 1988;37:495–498. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.John SA, Weiss JN, Ribalet B. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:391–405. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Proks, P., Antcliff, J. F., Lippiat, J., Gloyn, A. L., Hattersley, A. T., and Ashcroft, F. M. (2004) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Proks P, Girard C, Haider S, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, Sansom MS, Ashcroft FM. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:470–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larsson O, Barker CJ, Berggren PO. Diabetes. 2000;49:1409–1412. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin CW, Yan F, Shimamura S, Barg S, Shyng SL. Diabetes. 2005;54:2852–2858. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riedel MJ, Steckley DC, Light PE. Hum Genet. 2005;116:133–145. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nestorowicz A, Wilson BA, Schoor KP, Inoue H, Glaser B, Landau H, Stanley CA, Thornton PS, Clement J P t, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Permutt MA. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1813–1822. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.11.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]