Abstract

Objective

to evaluate the feasibility, potential and risks of an internet-based telemedicine network in developing countries of Western Africa.

Methods

a project for the development of a national telemedicine network in Mali was initiated in 2001, using internet-based technologies for distance learning and teleconsultations.

Results

the telemedicine network has been in productive use for 18 months and has enabled various collaboration channels, including North-South, South-South, and South-North distance learning and teleconsultations. It also unveiled a set of potential problems: a) limited pertinence of North-South collaborations when there are major differences in available resources or socio-cultural contexts between the collaborating parties; b) risk of induced digital divide if the periphery of the health system is not involved in the development of the network, and c) need for the development of local medical contents management skills.

Conclusion

the identified risks must be taken into account when desiging large-scale telemedicine projects in developing countries and can be mitigated by the fostering of South-South collaboration channels, the use of satellite-based internet connectivity in remote areas, and the valorization of local knowledge and its publication on-line.

INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine tools enable the communication and sharing of medical information in electronic form, and thus facilitate access to remote expertise. A physician located far from a reference center can consult his colleagues remotely in order to solve a difficult case, follow a continuing education course over the Internet, or access medical information from digital libraries. These same tools can also be used to facilitate exchanges between centers of medical expertise, at a national or international level 1–4.

The potential of these tools is particularly significant in countries where specialists are few, and where distances and the quality of the infrastructure hinder the movement of physicians or patients. Many of the French-speaking African countries are confronted with these problems, and, in particular, large and scarcely populated countries such as Mali (twice the size of France, 11 million inhabitants) and Mauritania (twice the size of France, 3 million inhabitants).

The usefulness and risks of these new communication and collaboration channels must be assessed before large-scale programs are launched. Prior experiences in the field include ISDN-based visioconference for tele-cardiology and tele-neurology between Dakar and Saint-Louis in Senegal, a demonstration project (FISSA) of the use of satellite-based prenatal tele-echography between Dakar and the Tambacounda region in Senegal, and tele-radiology experiences in Mozambique. However, there is little published material on the use of low-bandwidth, Internet-based telemedicine applications, although there is a significant investment in these technologies in developing countries.

The development of the national network for telemedicine in Mali was used as a pilot case in order to get a better insight into these aspects.

METHODS OF THE PILOT PROJECT

The project in Mali, named « Keneya Blown » (the “health vestibule” in Bambara language), was initated in 2001 by the Mali University Medical School in Bamako, and financed by the Geneva government and the Geneva University Hospitals. Several goals were set: a) develop and use Internet-based connections between the national and regional healthcare institutions, b) implement basic services such as e-mail and a medical Web portal, and train users, c) implement a low-bandwidth, Internet-based distance learning system, d) evaluate the feasibility of long distance collaborations for continuing medical education and teleconsultations.

The national network infrastructure is based on a IEEE 802.1 1b wireless metropolitan area network in Bamako, and on the numeric telephony network to reach regional hospitals.

The e-mail and Web services are hosted on Linux-based servers 5, protected from the unstability of electric power supply by three dozens of truck batteries.

The distance learning system 6, developed at Geneva University, is specifically designed to minimize the use of network bandwidth while providing high-quality sound and display of didactic material, as well as feedback from the students to the teachers via instant messaging. The student can adjust the quality of the video image of the “talking head”, which educational value is limited, in order to save resources. A bandwidth of 28 kbits/second is therefore sufficient and enables remote areas to participate in distance learning activities. It is based on free and widely available tools, browser-based, and works on most desktop operating systems (Table 1a and 1b).

Table 1a.

Hardware and software requirements of the distance learning client

|

Table 1b.

Hardware requirements for the distance learning server (webcasting equipment)

|

Similar projects, using the same technologies, are now being deployed in Mauritania, Morroco and Tunisia.

RESULTS OF THE PILOT PROJECT

Over 18 months, the project in Mali has enabled the development of a functional national telemedicine network, which connects several health institutions in Bamako, Segou and Tombouctou, where medical teams have been trained for the use of Internet-based tools. The medical Web portal is in place. Webcasting systems for distance learning have been implemented in Geneva and Bamako. Continuing medical education courses are now broadcast on a weekly basis. Several teleconsultations have taken place, to follow patients that were operated in Geneva and then returned to Mali. The teleconsultation system is also used to select appropriate cases and guide their work-up in order to optimize patients evacuation to hospitals in the North or to prepare humanitarian missions. The number of these consultations is currently limited by the number of partners in the network.

Various types of collaboration have been enabled by the project:

North-South tele-education: topics for post-graduate continuing medical education are requested by physicians in Bamako; courses are then prepared by experts in Switzerland and then broadcasted over the Internet from Geneva. New courses are produced and broadcasted on a bi-monthly basis, on a variety of topics (Table 2). The material is also saved and can be replayed from the medical Web portal. Typically, these courses are followed by 50 to 100 physicians and students in a specially-equipped auditorium in the Bamako University Hospital, and also by smaller groups or individuals in the Segou and Timbuktu regional hospitals, and in other french-speaking countries in Africa: Senegal, Mauritania, Chad, Morrocco, Tunisia.

Webcasting of scientific conferences: several sessions of international conferences have been broadcasted, with simultaneous translation in French, in order to make the presentations accessible to colleagues in Mali, where the practice of the english language is still limited. Using the instant messaging feature of the system, remote participants can intervene and ask questions to the speakers.

South-South tele-education: post-graduate and public health courses, developed by the various health institutions in Bamako, are webcasted to regional hospitals in Mali and to other partners in Western Africa (Figure 1). The contents produced is anchored in local, economical, epidemiological and cultural realities, and provides directly applicable information.

South-North tele-education: medical students training in tropical medicine in Geneva follow courses and seminars organized by experts in Mali on topics such as leprosy or iodine deficiency. The exposure to real- world problems and field experts enables a better understanding of the challenges for developing and implementing healthcare and public health projects in unfamiliar settings.

North-South tele-consultation: the same system can be used to send high-quality images enabling the remote examination of patients or the review of radiographic images. Tele-consultations are held regularly, in areas where expertise is not available in Mali, such as neurosurgery or oncology (Figure 2).

South-South tele-consultation: physicians in regional hospitals can request second opinions or expert advice from their colleagues in the university hospitals, via e-mail, including the exchange of images obtained using digital still cameras.

South-North tele-consultation: the case of a leprosy patient, followed in Geneva, has been discussed using the tele-consultation system, and enabled the expert in Bamako to adjust the treatment strategy.

Table 2.

Topics of distance learning courses requested by physicians in Bamako University Hospital (Mali)

|

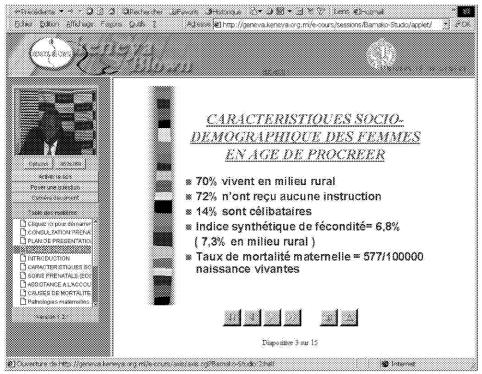

Figure 1.

Screenshot of a student view of course webcast, showing the teacher (top-left), the didactic documents (main window) and controls for the sound and the instant messaging tool (left column)

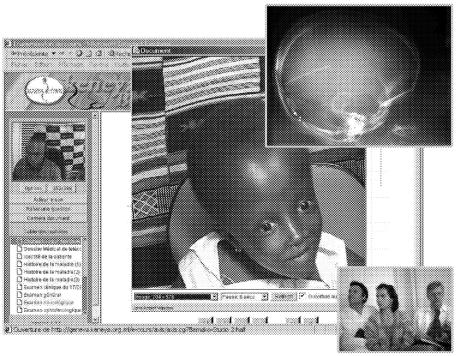

Figure 2.

Screenshot of a teleconsultation session, showing the various documents available: image of the patient, of the physicians, of radiographic images and other clinical data.

LESSONS LEARNED

At the infrastructure level, three kind of problems are identified: a) the unstability of basic infrastructure and in particular of the electric power supply; b) the limitation of the international bandwidth, which, is often misused, in particular by e-mail accounts hosted out of the country; and c) the unavailability of reliable connectivity beyond large cities. These problems are improving with the overall development of the national infrastructure, although the deregulation movements in the ICT sector and the deployment of mobile telephony will - at least initially-favor the most profitable markets, which are not those where telemedicine tools are most needed. For instance, the focus on mobile telephony probably limits investments in wired infrastructure that is needed for Internet access. Similarly, the deployment of wireless metropolitan area networks rapidly provide the needed connectivity, but should probably be gradually replaced by the more sustainable, wired, optical fibre-based communication infrastructure.

Basic communication tools such as e-mail are efficient and can be used productively. It is important to develop local capacity to implement and exploit these tools, not only to improve the technical expertise and the reliability of telemedicine applications, but also to limit the use of international bandwidth for information transfer that remains local. Most physicians in Mali still use US-based e-mail accounts for exchanges that remain local, due to a lack of reliable local e-mail services.

At the contents level, there is a steady demand for North-South distance learning. However, several topics for seminars, requested by physicians in Mali, could not be satisfactorily addressed by experts in Switzerland, due to major differences in diagnostic and therapeutic resources, and to discrepancies in the cultural or social contexts. For instance, there is no magnetic resonance imaging capability in Mali and the only CT-scanner has been unavailable for months. Chemotherapeutic agents are too expensive and their manipulation requires unavailable expertise. Even though diagnostic and therapeutic strategies could be adapted, practical experience is lacking, and other axes for collaboration must be found. A promising perspective is the fostering, through decentralized collaborative networks, of South-South exchanges of expertise. For example, there is neurosurgical expertise in Dakar, Senegal, which is a neighboring country to Mali. A tele-consultation between these two countries would make sense for two reasons: a) physicians in Senegal understand the context of Mali much better than those from northern countries, and b) a patient requiring neurosurgical treatment would most likely be treated in Dakar rather than in Europe.

Beyond contents, collaboration between the stakeholders of telemedicine applications must be organized, in order to guarantee the reliability, security, safety and timeliness for exchanging sensitive information, in particular when the communication is not synchronous. Computer-supported collaborative work environments have been developed. For example, the iPath project3, developed by the Institute of Pathology in Basel, organizes “virtual medical communities”, which replicate organizational models of institutions in distributed collaboration networks, including clearly identified responsible experts and on-call schedules. These new forms of collaboration over distances, across institutions, and sometimes across national borders also raise legal, ethical and economical questions, questions that are beyond the scope of this paper.

The “induced digital divide” is another potential problem. The centrifugal development of the communication infrastructure implies that the remote areas, where telemedicine tools could be most useful, will be served last. As in most developed countries, physicians are reluctant to practice in remote areas, and the ability to interact with colleagues and follow continuing medical education courses can be significant incentives. Besides the accessibility problem, this also influences the contents of the telemedicine tools, which typically will initially be geared towards tertiary care problems. It is therefore important to make sure that the needs of the periphery of the health system are taken into account. An efficient way to do so is to have the periphery connected early to the telemedicine network. Satellite-based technologies for Internet access, such as mini-VSAT, are sufficiently affordable to consider developing remote access points before the gound infrastructure becomes available.

Finally, there is a need to develop local content-management skills. Local medical contents is a key for the acceptance and diffusion of health information, and is also essential for productive exchanges in a network of partners. It enables the translation of global medical knowledge to the local realities, including the integration of traditional knowledge. Medical content-management requires several levels of skills: technical skills for the creation and management of on-line material, medical librarian skills for appropriate contents organisation and validation, and specific skills related to the assessment of the quality and trustworthiness of the published information, including the adherence to codes of conducts such as the HONcode 7.

PERSPECTIVES

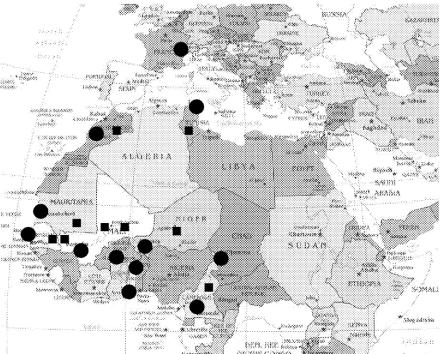

Based on the lessons learned during the pilot project, a larger, four-year project involving twelve countries of Western Africa is being launched in 2003: the RAFT project (Telemedicine Network in French-speaking Wester Africa, figure 3). The following aspects are emphasized:

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the institutions participating to the RAFT project. Circle represent teaching institutions located in capitals or large cities. Squares denote remote access points (fixed or mobile) connected via satellite links.

The development of a telemedicine infrastructure in teaching medical centers, and their connection to national and international computer networks, in order to foster multi-lateral medical expertise exchanges, with a predominant South-South orientation.

The use of asynchronous, collaborative environments that enable the creation of virtual communities and the control of workflow for getting expert advice or second opinions, in a way that is compatible with the local care processes. The open-source tool developed for telepathology at the University of Basel 3 is being implemented, not only for telepathology, but also for radiology and dermatology.

The deployment of internet access points in rural areas, with the use of satellite technology, enabling not only telemedicine applications but also other tools for assisting integrated, multi-sectorial development, and, in particular, education, culture and the local economy. The mini-VSAT technology, recently deployed over Western Africa, offers an affordable, ADSL-like connectivity. Sustainable economical models, based on the successful experiences with cybercafes in Africa, are being developed to foster the appropriation of this infrastructure by rural communities.

The development and maintenance of locally- and culturally-adapted medical contents, in order to best serve the local needs that are rarely covered by medical resources available on the internet. New tools are being developed: regionalized search engines, open source approaches, and adapted ethical codes of conduct. The Cybertheses project8 and the ressources from the the Health On the Net Foundation 7 are used to train physicians, medical documentalists and librarians.

CONCLUSION

Telemedicine tools have an important role to play in the improvement of the quality and efficiency of health systems in developing countries, as they offer new channels for communication and collaboration, and enable the dematerialization of several processes that are usually hindered by deficient physical infrastructures. They also expose some risks, and in particular the exchange of inappropriate or inadequate information, and the potential aggravation of local digital divide between the cities and the rural areas. These risks must be examined when designing telemedicine projects and can probably be mitigated by the development of South-South communication channels, the use of satellite-based technologies to incorporate remote areas in the process and by fostering a culture and skills for local medical contents management. These aspects are being further investigated by the RAFT project.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from the Geneva State government and Geneva University Hospitals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Graham LE, Zimmerman M, Vassallo DJ, et al. Telemedicine--the way ahead for medicine in the developing world. Trop Doct. 2003;33:36–8. doi: 10.1177/004947550303300118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganapathy K. Telemedicine and neurosciences in developing countries. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:388–94. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00924-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberholzer M, Christen H, Haroske G, et al. Modern telepathology: a distributed system with open standards. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;32:102–14. doi: 10.1159/000067381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright D. Telemedicine and developing countries. A report of study group 2 of the ITU Development Sector. J Telemed Telecare. 1998;4(Suppl 2):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.www.keneva.org.ml

- 6.www.unige.ch/e-cours

- 7.www.hon.ch

- 8.www.cybertheses.org