Abstract

According to the wobble rule, tRNA2Thr is nonessential for protein synthesis, because the codon (ACG) that is recognized by tRNA2Thr is also recognized by tRNA4Thr. In order to investigate the reason that this nonessential tRNA nevertheless exists in Escherichia coli, we attempted to isolate tRNA2Thr-requiring mutants. Using strain JM101F−, which lacks the gene for tRNA2Thr, we succeeded in isolating two temperature-sensitive mutants whose temperature sensitivity was complemented by introduction of the gene for tRNA2Thr. These mutants had a mutation in the htrB gene, whose product is an enzyme involved in lipid A biosynthesis. Although it is known that some null mutations in the htrB gene give a temperature-sensitive phenotype, our mutants exhibited tighter temperature sensitivity. We discuss a possible mechanism for the requirement for tRNA2Thr.

Recently, Nakayashiki and Inokuchi (20) investigated the role of tRNA6Leu, one of the nonessential tRNAs in Escherichia coli. They succeeded in isolating tRNA6Leu-requiring temperature-sensitive mutants and identified the responsible mutations in the genes miaA and gidA. The miaA gene encodes an enzyme that catalyzes the modification of tRNA (2, 5), and the gidA gene seems to be involved in cell division (6, 9). Although the function of nonessential tRNA6Leu remained obscure, the necessity for it was convincingly demonstrated.

In this paper, we report a similar study of tRNA2Thr. The anticodon of tRNA2Thr is CGU, and it recognizes only the codon ACG (17). According to the wobble rule (10), the codon ACG is also recognized by tRNA4Thr, which has a UGU anticodon. Thus, tRNA2Thr may not be essential for protein synthesis. In fact, a strain with a large deletion from the proAB gene to the lac gene, including the region in which the thrW gene for tRNA2Thr is located, has been characterized, and this deletion strain can grow without any deficiency.

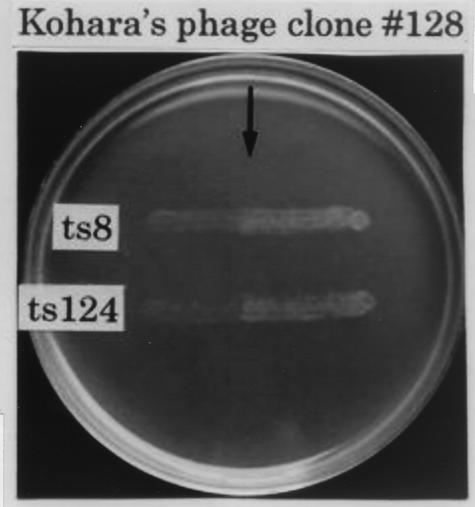

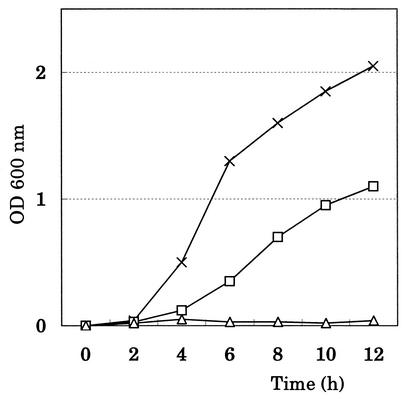

In order to identify a new function of tRNA2Thr other than that of a tRNA in protein synthesis, we attempted to isolate tRNA2Thr-requiring mutants from the strain JM101F−, which has a pro-lac deletion that includes the gene for tRNA2Thr, by employing the same procedure that was previously used in the case of tRNA6Leu. Among 200 independent temperature-sensitive mutants isolated from JM101F−, we screened for mutants whose temperature sensitivity was suppressed by infection with Kohara's phage clone 128 (16), which carries the wild-type gene for tRNA2Thr (thrW). Because Kohara's phage clone is cI−, the JM101F− strain was lysogenized with the wild-type λ phage in advance. As shown in Fig. 1, two mutants were thus identified as Kohara's phage clone 128-requiring mutants. The patterns of growth for these two mutants were compared with those of parental strain JM101F−. Strain ts8 showed tighter temperature sensitivity than ts124, as shown in Fig. 2. Because it is known that Kohara's phage clone 128 carries eight open reading frames (ORFs) and the thrW gene (3), we performed complementation tests for the two mutants by using eight different plasmid clones, each possessing a single ORF (19). Complementation was not observed with any of the eight ORF plasmid clones, but it was observed with the plasmid carrying a single thrW gene (the gene for tRNA2Thr) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Complementation of temperature-sensitive mutants (ts8 and ts124) derived from strain JM101F− by cross-streaking with Kohara's phage clone 128 (16). An overnight culture of each temperature-sensitive mutant grown in lambda broth at 32°C was streaked left to right horizontally over Kohara's phage clone 128, which had been streaked vertically on a lambda plate (11). The plate was incubated at 42°C overnight and photographed. JM101F−, which is a derivative of JM101 (22) that cures F′ (proAB-lac) spontaneously, was screened by testing pro and lac markers. Temperature-sensitive mutants were isolated after mutagenesis with N-methyl-N′-nitrosoguanidine (18). The isolation procedure was as described by Nakayashiki and Inokuchi (20).

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of the temperature-sensitive mutants. Overnight cultures of the bacteria grown at 32°C in Luria-Bertani medium were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.005. The diluted cultures were shaken at 42°C. Aliquots were withdrawn at every 2 h and the OD600 was measured by using a model UV-160A Shimadzu spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). Symbols: ×, JM101F−; ▵, ts8; □, ts124.

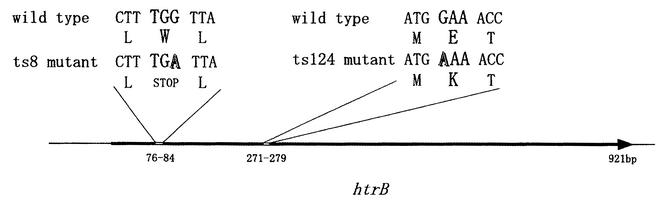

In order to identify the mutated genes, we carried out complementation tests by using the miniset clones of Kohara's library (16). Both temperature-sensitive mutants were weakly complemented by Kohara's phage clone 128 and strongly complemented by clones 232 and 233. Because it is known from sequence data that 10 ORFs are located in the overlapping region of Kohara's phage clones 232 and 233, we carried out complementation tests by using a series of 10 plasmid clones that each carried only a single ORF (19). The complementation tests showed that clone 11-5E, which carries the htrB gene encoding an enzyme involved in lipid A biosynthesis, gave a positive result. Furthermore, in order to determine the mutation(s), we sequenced the htrB gene from both mutants. As illustrated in Fig. 3, mutant ts124 had a missense mutation in the htrB gene caused by a change of nucleotide 81 from G to A, and the other mutant, ts8, had a nonsense mutation caused by a change of nucleotide 274 from G to A.

FIG. 3.

Schematic presentation of the mutations in the temperature-sensitive mutants, ts8 and ts124. PCR was carried out by using genomic DNA from the mutant bacteria as a template and two primers, 5′-GCACACGAATTCTGCGCCCGACTTC-3′ and 5′-GATATAGGAATTCTCGATAATTAAC-3′. The resultant fragments (1.2 kb) were cloned into the EcoRI site of pUC18. Plasmids were isolated by the alkaline lysis method (4). The methods used for digestion with restriction enzyme, agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA ligation, were those described by Sambrook et al. (21). DNA was sequenced by the chain termination method by using materials and protocols from a DYEnamic ET terminator cycle sequencing kit. Eight sequencing primers for the 1.2-kb insert were synthesized by KURABO Co. (Osaka, Japan). To avoid PCR errors, three independent clones were used for sequencing. Shadowed letters in the figure indicate mutated bases.

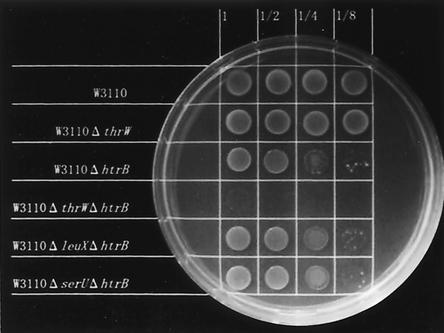

It has been reported that null mutations in the htrB gene result in a temperature-sensitive phenotype (13, 15). Indeed, our experiments showed a similar result. We constructed a series of mutant strains which had the same genetic background as W3110, including W3110 ΔleuX::Kmr and W3110 ΔserU::Cmr as controls. The single-deletion mutant W3110 ΔthrW::Kmr was able to grow as well as the wild-type W3110. The single deletion mutant W3110 ΔhtrB::Tetr showed temperature sensitivity, as described previously. The double deletion mutant W3110 ΔthrW::Kmr ΔhtrB::Tetr could not grow at all at 42°C, as shown in Fig. 4. This phenomenon was found only in the case of the ΔthrW::Kmr ΔhtrB::Tetr strain and not in the case of double deletion mutants with the other tRNA genes tested, namely, ΔleuX::Kmr ΔhtrB::Tetr and ΔserU::Cmr ΔhtrB::Tetr. These results clearly indicate that the thrW gene (tRNA2Thr), but not other tRNA genes (the tRNA6Leu and tRNA2Ser genes), is able to overcome the temperature sensitivity caused by a null mutation in the htrB gene and that this complementation is specific for the thrW gene (tRNA2Thr).

FIG. 4.

Growth comparisons of the deletion mutants in the various tRNA genes and in the htrB gene of the isogenic strain. W3110 wild-type and mutant bacteria were cultured overnight in Luria-Bertani medium at 32°C, diluted, and spotted on a Luria-Bertani plate. The plate was incubated at 42°C overnight and photographed. The ΔleuX deletion mutant was described previously (21). Other deletion mutants used in this experiment were constructed by following the same procedures described in reference 21: leuX and thrW were replaced by the kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene from pUC4KAPA (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and serU was replaced by the chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) gene from pHSG399 (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan). The htrB1::Tn10 marker (tetracycline resistance [Tetr] gene) in strain MLK53 (13) and other drug resistance markers were moved with phage P1-mediated transduction into the wild-type strain W3110 in our laboratory stocks. The replacement of drug resistance genes in the mutant strains was verified by DNA sequencing of PCR products amplified from the regions including the junction between the drug resistance gene and host chromosome.

The htrB gene encodes an enzyme involved in lipid A biosynthesis (7). It was reported that the htrB gene is essential for viability at temperatures above 32.5°C in rich medium (12, 14) and that intergenic suppressors are able to suppress the mutant phenotype; i.e., htrB null mutants were suppressed by mutations in the accBC operon (8), by introduction of the msbB gene on high-copy-number plasmids (8), and by introduction of the msbA gene on low-copy-number plasmids (15). These studies indicated that the temperature sensitivity of htrB mutants is caused by a disturbance of the relationship between the growth rate and the rate of phospholipid biosynthesis at high temperature.

In order to explain the novel function of tRNA2Thr detected in this study, we will discuss the following possibilities. The first possibility is that tRNA2Thr interacts with HtrB products. This possibility was ruled out by the fact that the htrB gene was completely deleted in our experiments. However, it remains possible that tRNA2Thr affects the expression of the htrB gene. Another possibility is that the lack of tRNA2Thr affected the relationship between the growth rate and the rate of phospholipid biosynthesis in some way. For example, tRNA2Thr may be required for the synthesis of MsbA and/or MsbB. The usages of codon ACG (this codon is recognized by tRNA2Thr) in msbA and msbB are 1.72 and 2.17, respectively. These values are larger than the overall value for all ORFs in E. coli (1.14) (1). Moreover, the msbB gene has no ACA codon. Therefore, the synthesis of MsbB might mainly require tRNA2Thr. It is possible that the amount of MsbA and/or MsbB is strongly affected by the lack of tRNA2Thr in the deletion mutant. Thus, the suppression by tRNA2Thr observed in the present study may be due to some relationship between MsbA and/or MsbB and tRNA2Thr. The experiments on mutational exchange of ACG codon by ACA in the msbA and msbB genes should prove most important. A third possibility is that tRNA2Thr may inhibit phospholipid biosynthesis, an effect that might also be caused by mutations in the accBC operon (13). In any case, it seems clear that tRNA2Thr may be a key factor in the balance between the growth rate and the rate of phospholipid biosynthesis. Further biochemical studies would help to resolve this issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Georgopoulos for providing the strain MLK53 (htrB1::Tn10). We also thank H. Mori, Nara Institute of Science and Technology, for providing the plasmid clones, which were prepared as a complete set of each E. coli ORF cloned in a plasmid vector.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (no. 12029213) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan. H.I. was a member of the E. coli Genome Project Team of Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) supported by JST.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aota, S., T. Gojobori, F. Ishibashi, T. Maruyama, and T. Ikemura. 1988. Codon usage tabulated from the GenBank genetic sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 16(Suppl.):r315-r402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, T., M. Takanami, and M. Imai. 1990. The AT richness and gid transcription determine the left border of the replication origin of the E. coli chromosome. EMBO J. 9:4065-4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buhk, H. J., and W. Messer. 1983. The replication origin region of Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and function units. Gene 24:265-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caillet, J., and L. Droogmans. 1988. Molecular cloning of the Escherichia coli miaA gene involved in the formation of 2-isopentenyl adenosine in tRNA. J. Bacteriol. 170:4147-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clementz, T., J. J. Bednarski, and C. R. Raetz. 1996. Function of the htrB high temperature requirement gene of Escherichia coli in the acylation of lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 271:12095-12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clementz, T., Z. Zhou, and C. R. Raetz. 1997. Function of the Escherichia coli msbB gene, a multicopy suppressor of htrB knock-outs, in the acylation of lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10353-10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly, D. M., and M. E. Winkler. 1989. Genetic and physiological relationships among the miaA gene, 2-methylthio-N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)-adenosine tRNA modification, and spontaneous mutagenesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 171:3233-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crick, F. H. C. 1966. Codon-anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. J. Mol. Biol. 19:548-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inokuchi, H., F. Yamao, H. Sakano, and H. Ozeki. 1979. Identification of transfer RNA suppressors in Escherichia coli. I. Amber suppressor su+2, an anticodon mutant of tRNAGln2. J. Mol. Biol. 132:649-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karow, M., O. Fayet, A. Cegielska, A., T. Ziegelhoffer, and C. Georgopoulos. 1991. Isolation and characterization of the Escherichia coli htrB gene, whose product is essential for bacterial viability above 33° C in rich media. J. Bacteriol. 173:741-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karow, M., O. Fayet, and C. Georgopoulos. 1992. The lethal phenotype caused by null mutations in the Escherichia coli htrB gene is suppressed by mutations in the accBC operon, encoding two subunits of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. J. Bacteriol. 174:7407-7418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karow, M., and C. Georgopoulos. 1991. Sequencing, mutational analysis, and transcriptional regulation of the Escherichia coli htrB gene. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2285-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karow, M., and C. Georgopoulos. 1993. The essential Escherichia coli msbA gene, a multicopy suppressor of null mutations in the htrB gene, is related to the universally conserved family of ATP-dependent translocators. Mol. Microbiol. 7:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohara, Y., K. Akiyama, and K. Isono. 1987. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell 50:495-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komine, Y., T. Adachi, H. Inokuchi, and H. Ozeki. 1990. Genomic organization and physical mapping of the transfer RNA genes in Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol. 212:579-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Mori, H., K. Isono, T. Horiuchi, and T. Miki. 2000. Functional genomics of Escherichia coli in Japan. Res. Microbiol. 151:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakayashiki, T., and H. Inokuchi. 1998. Novel temperature-sensitive mutants of Escherichia coli that are unable to grow in the absence of wild-type tRNA6Leu. J. Bacteriol. 180:2931-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. J. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]