Abstract

Nocturnal acid breakthrough is defined as the presence of intragastric pH < 4 during the overnight period for at least 60 continuous minutes in patients taking a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). Nocturnal acid breakthrough occurs in more than 70% of Helicobacter pylori-negative patients on PPI therapy and has clinical consequences in particular in patients with complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal motility abnormalities. The clinical importance of nocturnal acid breakthrough and the benefit of adding histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) to PPI therapy have been debated ever since these concepts were introduced. In our experience, the addition of bedtime H2RAs is clinically effective in controlling nocturnal acid breakthrough and GERD symptoms.

Introduction

The final step in gastric acid secretion is the exchange of intracellular protons (H+) for extracellular potassium (K+). The energy required to transfer protons across the high concentration gradient (intracellular pH is approximately 7 while the intragastric pH is close to 1) comes from cleaving ATP molecules. The H+/K+ ATP-ase responsible for this process is also known as the "proton pump," and is inhibited by substituted benzimidazoles or PPIs. The introduction of PPIs in the 1980s changed the clinical approach to and management of peptic diseases such as gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and GERD.

The initial, basic science reports on the PPIs described these medications as irreversible inhibitors of the proton pump, underscoring the need for synthesis of new proton pumps before acid secretion could be resumed.[1] The concern about iatrogenic achlorhydria and its consequences led to an initial "black box" warning regarding the duration of treatment with PPIs. Subsequent clinical data revealed that PPIs, even though they significantly decrease acid secretion, do not completely eliminate intragastric acidity.[2] Reasons for this phenomenon include the relative short serum half-life of PPIs (2-4 hours), the fact that not all proton pumps are active at the same time, and that generation of new proton pumps is a continuous process.[3] Recovery of intragastric acidity, primarily during nighttime while on PPI therapy, should not be regarded as a failure of, or resistance to, these compounds, but rather as an expected phenomenon that may require attention in some patients.

What Is Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough?

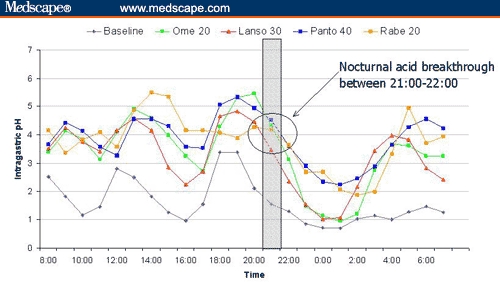

Peghini and colleagues[4] were the first to introduce the term "nocturnal acid breakthrough," and defined it as gastric acid recovery to a pH level < 4 for at least 60 consecutive minutes in the overnight period (10:00 PM to 6:00 AM). The study authors analyzed intragastric 24-hour pH profiles in a series of 45 patients treated with PPIs twice daily and identified that it occurred in 70% of patients during the nighttime period. Subsequently, this pharmacologic phenomenon was reported with equal frequency with omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and pantoprazole, and was demonstrated in both healthy subjects and patients with GERD.[5] Nocturnal acid breakthrough was also noted during daily dosing with esomeprazole; only 45% of healthy volunteers taking twice-daily esomeprazole 20 mg exhibited nocturnal acid breakthrough.[6] The onset of nocturnal acid breakthrough depends on the timing of PPI administration. In subjects taking PPIs once daily before breakfast, the event occurs early in the evening, beginning around 10:00 PM,[7] while in subjects taking PPIs twice daily before breakfast and dinner, nocturnal acid breakthrough occurs 6-7 hours after the evening dose of the PPI (some time between 1:00 and 4:00 AM). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Twenty-four-hour intragastric pH profiles of daily-dosed PPIs. Note the beginning of nocturnal acid breakthrough between 9:00 and 10:00 PM for all PPIs.[7]

Key: Ome 20 = omeprazole 20 mg (oral) every morning; Lanso 30 = lansoprazole 30 mg (oral) every morning; Panto 40 = pantoprazole 40 mg (oral) every morning; Rabe 20 = rabeprazole 20 mg (oral) every morning.

Recent studies have reported on the relationship between H pylori status and presence of nocturnal acid breakthrough. Recording intragastric pH data in 15 asymptomatic H pylori-positive volunteers, Martinek and colleagues[8] reported on the presence of at least 60 continuous minutes of intragastric pH < 4 during nighttime in almost all (93%) H pylori-positive individuals when not taking PPIs. Only 8 (53%) of these individuals had nocturnal acid breakthrough when receiving omeprazole 20 mg daily, and nocturnal acid breakthrough was not present in any of the 15 subjects when receiving omeprazole 20 mg twice daily. The effect of H pylori on nocturnal acid breakthrough is not related to a specific PPI, despite other studies reporting a decreased incidence of nocturnal intragastric acidity in H pylori-positive patients on lansoprazole,[9] rabeprazole,[10] and pantoprazole.[11] The influence of H pylori status on nocturnal acid breakthrough is likely related to the hypochlorhydria observed in patients with H pylori-associated gastritis and the production of ammonia by the organism.[12] In H pylori-negative patients, the secretion of acid is not impaired by the inflammatory response or the presence of increased amounts of ammonia in the gastric lumen. Therefore, acid production is more likely to recover after pharmacologic suppression with PPIs.

Clinical Importance of Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough

Most individuals are recumbent during nighttime and do not swallow as frequently as during daytime. Without the assistance of gravity and with decreased salivary buffering, esophageal acid clearance depends primarily on esophageal peristalsis. Therefore, nocturnal acid breakthrough is of particular importance in patients with complicated GERD, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal motility abnormalities. The importance of these previously mentioned mechanisms is supported by clinical studies. Fouad and colleagues[5] found that at least 50% of patients with Barrett's esophagus and scleroderma with GERD had increased overnight esophageal acid exposure during nocturnal acid breakthrough. In a similar study, Katz and colleagues[13] found that patients with decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure and ineffective esophageal motility (ie, high frequency of distal esophageal body contractions < 30 mmHg) who had nocturnal acid breakthrough were 8 times more likely to reflux during gastric acid breakthrough compared with those individuals without nocturnal acid breakthrough.

The clinical importance of nocturnal acid breakthrough in healthy volunteers and patients with mild GERD is more controversial. Ours and colleagues[14] studied the association of esophageal pH with nocturnal acid breakthrough in a group of 22 subjects, both healthy volunteers (n = 9) and patients with GERD (n = 13). Each participant received various regimens of acid-suppressive medications; nocturnal acid breakthrough was present in 91% of individuals when receiving PPI therapy in the morning and at bedtime, in 82% when receiving PPI therapy twice daily (before breakfast and before dinner), in 82% when receiving PPI therapy every 8 hours independent of meals, and in 59% of subjects when twice-daily PPI therapy (before meals) was combined with bedtime H2RAs. While achieving symptom control in all 13 patients with GERD, the investigators did not find a correlation between nocturnal acid breakthrough and esophageal acid exposure, concluding that nocturnal acid breakthrough is an isolated gastric phenomenon and esophageal acid suppression and symptom control are not dependent on the degree of nocturnal acid breakthrough elimination.

These apparently controversial studies raise concern about the clinical significance of nocturnal acid breakthrough. The phenomenon is probably of limited importance in patients with uncomplicated GERD and in patients with normal esophageal clearance mechanisms. However, the presence of nocturnal acid breakthrough in patients with impaired esophageal clearance and/or complicated GERD may not be trivial. Future studies clarifying the clinical relevance of nocturnal acid breakthrough are warranted.

Treatment of Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough

The maximal benefit from PPI therapy is achieved when PPIs are taken 15-30 minutes before meals, allowing optimal blood concentrations of the drug at the time of meal-induced activation of proton pumps, to produce blockade of a large number of pumps.[15] Normally, there is no food ingestion during nighttime, and so bedtime dosing of another agent (ie, H2RAs) should be considered for the additional inhibition of nocturnal acid secretion.

Peghini and colleagues[16] were the first to investigate the role of adding H2RAs to PPI therapy to control nocturnal acid breakthrough. In this study, 12 healthy volunteers taking omeprazole 20 mg before breakfast and dinner were randomized to receive placebo, ranitidine 150 mg, ranitidine 300 mg, or omeprazole 20 mg at bedtime in a double-blind design. The addition of a PPI at bedtime was statistically superior to placebo in decreasing nocturnal acid breakthrough, but the third PPI dose at bedtime was statistically inferior to both doses of ranitidine in controlling nocturnal acid breakthrough. On the first day that ranitidine was added to the regimen, only one third of subjects were found to have nocturnal acid breakthrough.

The addition of a bedtime H2RA does not substitute the need for a second dose of PPI before dinner. This concept was investigated by Khoury and colleagues[17] in a randomized, cross-over study comparing nocturnal acid control in 20 healthy subjects receiving a 7-day course of either omeprazole 20 mg twice daily (before meals) or omeprazole 20 mg before breakfast and ranitidine 150 mg before bedtime. The finding that overnight intragastric pH control was superior when subjects received omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, compared with omeprazole 20 mg before breakfast and ranitidine 150 mg before bedtime, provides support for the approach that H2RAs should be used in addition to and not instead of PPI therapy given twice daily before breakfast and dinner.

The use of H2RAs in addition to twice-daily PPI therapy has been challenged over the years. Initially, Fackler and colleagues[18] raised concern regarding the potential development of tolerance to H2RAs, suggesting that the addition of H2RAs to a twice-daily PPI regimen might reduce nocturnal acid breakthrough only temporarily, and that after 1 week or 1 month of therapy, tolerance to H2RAs may develop, decreasing the efficacy of the combination therapy. The clinical significance of tolerance to H2RAs needs to be further evaluated because a previous report by Xue and colleagues[19] showed that only 32% of 57 patients with GERD who were treated with twice-daily PPI therapy and an H2RA at bedtime for at least 30 days had nocturnal acid breakthrough, compared with 82% of 60 patients with GERD who were treated for at least 30 days with twice-daily PPIs only. It should also be noted that prior to the introduction of PPIs, H2RAs were successfully used for the long-term treatment of patients with GERD.

More recently, Ours and colleagues[14] reported on the lack of additional benefit achieved when H2RAs were added to twice-daily PPI therapy and compared with PPI therapy given every 8 hours. Unfortunately, this conclusion is based on an inadequately powered study (ie, a post-hoc power calculation revealed that the study sample size had only a 38% power of detecting a difference between PPIs given every 8 hours and twice-daily PPI therapy + H2RAs) with a high likelihood of a type 2 statistical error.

Conclusion

In conclusion, nocturnal acid breakthrough frequently occurs in H pylori-negative patients taking daily or twice-daily PPIs. In asymptomatic patients on PPI therapy with uncomplicated GERD, the clinical importance of nocturnal acid breakthrough is likely low. However, in patients with complicated GERD, Barrett's esophagus, esophageal motility abnormalities, and symptomatic patients on PPI therapy, nocturnal acid breakthrough should be investigated and treated. In our experience, we have found bedtime H2RAs to be an effective treatment for nocturnal acid breakthrough.

Contributor Information

Radu Tutuian, Fellow in Gastroenterology, Division of Gastroenterology-Hepatology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.

Donald O Castell, Professor of Medicine, Director of Esophageal Disease Program, Division of Gastroenterology-Hepatology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.

References

- 1.Richardson P, Hawkey CJ, Stack WA. Proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacology and rationale for use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs. 1998;56:307-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite LP, Johnston BT, Just RJ, Castell DO. Persistent acid secretion during omeprazole therapy: a study of gastric acid profiles in patients demonstrating failure of omeprazole therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1527-1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn J. The proton-pump inhibitors: similarities and differences. Clin Ther. 2000;22:266-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peghini PL, Katz PO, Bracy NA, Castell DO. Nocturnal recovery of gastric acid secretion with twice daily dosing of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouad YM, Katz PO, Castell DO. Oesophageal motility defects associated with nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux on proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1467-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammer J, Schmidt B. Effect of splitting the dose of esomeprazole on gastric acidity and nocturnal acid breakthrough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 200415;19:1105-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. A PPI is a PPI is a PPI: lessons from prolonged intragastric pH monitoring. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinek J, Pantoflickova D, Hucl T, et al. Absence of nocturnal acid breakthrough in Helicobacter pylori-positive subjects treated with twice-daily omeprazole. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:445-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Herwaarden MA, Samsom M, Smout AJ. Helicobacter pylori eradication increases nocturnal acid breakthrough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:961-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsube T, Adachi K, Kawamura A, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection influences nocturnal acid breakthrough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1049-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tutuian R, Katz PO, Bochenek WJ, Castell DO. Dose-dependent control of intragastric pH by pantoprazole 10, 20 and 40 mg in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:473-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman M, Cryer B, Sammer D, Lee E, Spechler SJ. Influence of H. pylori infection on meal-stimulated gastric acid secretion and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1159-G1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz PO, Anderson C, Khoury R, Castell DO. Gastro-oesophageal reflux associated with nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough on proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1231-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ours TM, Fackler WK, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. Nocturnal acid breakthrough: clinical significance and correlation with esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:545-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo B, Castell DO. Optimal dosing of omeprazole 40mg daily: effects on gastric and esophageal pH and serum gastrin in healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1532-538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peghini PL, Katz PO, Castell DO. Ranitidine controls nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough on omeprazole: a controlled study in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1335-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoury RM, Katz PO, Hammod R, et al. Bedtime ranitidine does not eliminate the need for a second dose of omeprazole to suppress nocturnal gastric pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fackler WK, Ours TM, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Long-term effect of H2RA therapy on nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue S, Katz PO, Banerjee P, Tutuian R, Castell DO. Bedtime H2 blockers improve nocturnal gastric acid control in GERD patients on proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1351-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]