Abstract

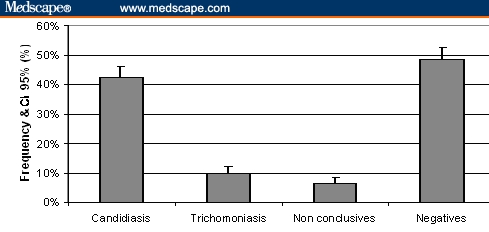

We aimed to estimate the prevalence of Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis in immunocompetent pregnant women living in Havana City, Cuba, with or without symptoms of vaginitis, using a sample of 640 women from 6 Gyneco-obstetrics hospitals, which represents 2.5% of total yearly pregnant women. Diagnosis was made using a new latex agglutination kit (Newvagin C-Kure, La Habana, Cuba). Clinical sensitivity and specificity of this assay were validated against culture method, with 467 and 489 clinical specimens for Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis, respectively. Results showed that the kit clinical sensitivity was 100% for Candida albicans and 86.7% for Trichomonas vaginalis compared with a clinical specificity of 93.3% for Candida albicans and 95.1% for Trichomonas vaginalis by culture. The prevalence of candidiasis was determined to be 42.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.8%); the prevalence of trichomoniasis was 9.84% (95% CI 2.3%). In our sample, 48.7% of the women tested negative with respect to both candidiasis and trichomoniasis. Only 6.41% of the cases yielded inconclusive results. The test has high sensitivity , and our results indicate a relatively high prevalence of both infections. However, a significant difference (P < .001) was also observed in candidiasis and trichomoniasis prevalence among hospitals corresponding to the quantity of women with clinical vaginitis. No difference was observed between diabetics and nondiabetics, probably due to the special care of diabetic pregnant women. We conclude that the method is useful for this kind of vaginitis prevalence study and that candidiasis and trichomoniasis prevalences in pregnant women of Havana are 38.5% to 46.2 % (95% CI) and 7.5% to 12.1% (95% CI), respectively.

Introduction

Infectious vaginitis is a common problem encountered in clinical medicine and is a frequent reason that women visit an obstetrician or gynecologist. Vulvovaginal candidiasis is the most common cause of vaginitis in Europe and the second most common cause of vaginitis in the United States.[1]Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated species, but other non-albicans species of Candida (C glabrata and C tropicalis) are also found. The incidence of candidiasis is almost doubled in pregnant women -- particularly in the third trimester -- compared with nonpregnant women; there also seems to be a trend for it to recur during pregnancy as a result of the increased levels of estrogens and corticoids reducing the vaginal defense mechanisms against such opportunistic infections as Candida.[2]

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan that is considered to be sexually transmitted. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the worldwide prevalence of trichomoniasis to be 174 million and to account for 10% to 25% of vaginal infections.[3] It is an important complication in pregnancy, as it has been related with prematurity and low birth weight.[4]

Diagnosis of nonviral infectious diseases of the vagina has been largely contingent on the clinician's ability to do a sophisticated wet mount/potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation examination.[5] However, diagnosis relies on observing the presence of hyphae or pseudohyphae for candidiasis and the presence of the protozoan for trichomoniasis. Microscopic examination of the saline fresh mounts is somewhat subjective; correct diagnosis can be elusive, complicating treatment and making it difficult to determine accurate prevalence rates.[6-9] Indeed, several studies using this method to establish the prevalence of the most common infectious agents for vaginitis have shown widely varying results, which may in part actually be due to inaccurate diagnoses.[10-19]

Immunologic tests, on the other hand, are simple to perform, generate immediate results, and should be useful for prevalence studies because of the homogeneity of the method. The objective of this study was to use a new latex agglutination test to determine the prevalence of Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis in a sample of immunocompetent pregnant women, with or without symptoms of vaginitis, in Havana.

Materials and Methods

Validation of the Diagnostic Kit

The evaluated parameters were analytic specificity (cross-reactions) and clinical sensitivity and specificity. The detection limit used was 106 cells/mL for Trichomonas vaginalis and 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL for Candida albicans.

The analytic specificity was determined by cross-reacting each type of latex with positive samples of the other agent. Cross-reaction tests used concentrations of Trichomonas vaginalis of 108 cells/mL for Candida latex and Candida albicans of 108 CFU/mL for Trichomonas latex. Both types of latex were evaluated against a sample with 108 CFU/mL of Gardnerella vaginalis and a confirmed multiple-specimen negative control.

For the trial of clinical sensitivity and specificity, 525 clinical samples were obtained. The study was carried out in the same hospital (Hospital C) as the prevalence study, using specimens from women with a diagnosis of vaginitis attending Hospital C's laboratory. These specimens were evaluated using the kit and reference methods. For Trichomonas vaginalis, the reference method was culture in Diamond medium with observation of the parasite; for Candida albicans, the method was culture in Saboraud medium and observation of the yeast colonies.

Prevalence Study

All pregnant women in Cuba receive their prenatal care at no cost. They are treated in their neighborhood by a community physician from the time of diagnosis until the second trimester, if no complications or diseases are present. In the lasts months of pregnancy they are attended at regional obstetrics hospitals. For the purposes of this study, pregnant women attended by the obstetrics services of the 6 major Gyneco-obstetrics hospitals in Havana City (designated here as Hospital A through F) for any reason, 1 day of the week for each hospital during 1 year (from 2001 to 2002), were sampled to obtain vaginal specimens for immunoreaction. Specimens were obtained from 640 non-HIV-infected, hospitalized and nonhospitalized pregnant women who consented to participate. Women were checked for signs and symptoms of vaginitis. This sample corresponded to around 2.5% of the total pregnant population of Havana.

The presence of Candida albicans in concentrations >10 6 CFU/mL (considering normal flora misinterpretation) and Trichomonas vaginalis in concentrations 106 cells/mL were determined in 3 minutes by a simultaneous simple method using latex particle agglutination, following manufacturer instructions (Newvagin C-Kure, La Habana, Cuba).

All collected data were introduced in an MS ACCESS database. Prevalence and confidence intervals (with 5% error) were calculated using the WINEPI - RATIOS (2.0) software, analysis of variance and Chi2 with SAS (version 6.14).

Results - Kit Validation

Cross-reactions of the Trichomonas vaginalis latex with the positive control of Candida albicans were not observed; neither did the latex of Candida albicans react with the positive control of Trichomonas vaginalis. Neither type of latex reacted with a suspension of Gardnerella vaginalis; nor did they react with the negative control.

Twenty-one (4%) of the clinical samples reacted with the negative control, which is nonspecific rabbit gammaglobulin bound to latex particles, and were classified as inconclusive; usually this is due to the presence of blood or sperm in the sample. Of the 504 remaining samples, it was possible to obtain results of both culture and immunologic methods in 467 samples for Candida albicans and 489 for Trichomonas vaginalis.

Tables of 2 x 2 (Table 1) were used to calculate the clinical sensitivity and specificity that are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

True and False Positives and Negatives -- Observed Values in 489 Clinical Specimens for Trichomonas vaginalis and 467 for Candida albicans Evaluated by Culture and by Latex Bound to Specific Antiglobulins

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Culture (Diamond) | ||

| Positives | Negatives | ||

| Latex | Positives | TP = 13 | FP = 23 |

| Negatives | FN = 2 | TN = 451 | |

| Candida albicans | Culture (Saboraud) | ||

| Positives | Negatives | ||

| Latex | Positives | TP =18 | FP = 30 |

| Negatives | FN =0 | TN = 419 | |

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity Observed for the Candida and Trichomonas Latex Kit

| Globulin Latex | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti Candida albicans | 100.00 | 93.32 | 467 |

| Anti Trichomonas vaginalis | 86.67 | 95.15 | 489 |

Candidiasis and Trichomoniasis Prevalence Study

The 6 hospitals are designated A through F. Sample distribution by hospital was as follows: A, 92 (14.4%); B, 51 (8.0%); C, 145 (22.7%); D, 77 (12.0%); E, 45 (7.0%); and F, 230 (35.9%). Hospital F contributed the highest number of cases (39.8%) and Hospital D contributed the least (7.8%).

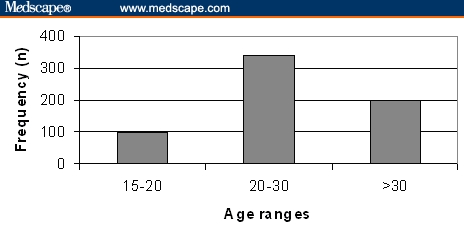

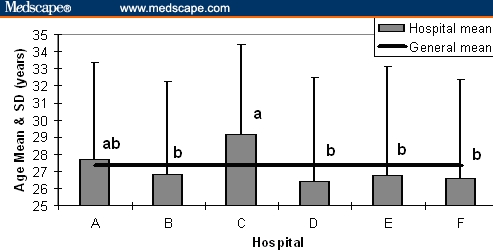

The age distribution of pregnant women sampled from the 6 hospitals was significantly different (P < .001) (Figure 1). Most of the patients were 20 to 30 years of age. The next most frequent age groups were > 30 years and < 20 years; only 2 women were older than 40 years of age. Among hospitals, only Hospital C had pregnant women who were significantly older than the average (2 years, P < .0009) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of pregnant women by age ranges: < 15, 15-20, 20-30, 30-40, and > 40 years.

Figure 2.

General age average and range distribution by hospital. Different letters, P < .009.

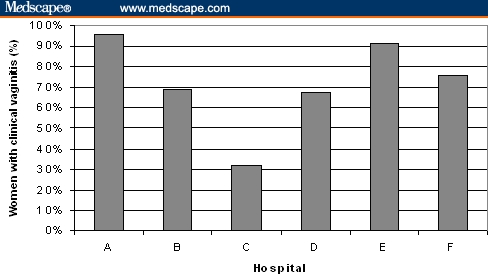

The frequency of vaginitis symptoms and signs is shown in Table 3. Vaginal discharge was the most commonly observed symptom in women with candidiasis and in women with trichomoniasis, but it was reported in < 60% of the women in the total sample. Abdominal pain, colpitis, and vulvar pruritus were other common recorded symptoms and signs. Difference (P < .001) between hospitals with regard to the percentage of attended women with signs or symptoms of vaginitis is shown in Figure 3. Hospital A had the higher contribution and Hospital C the lower one.

Table 3.

Most Frequent Symptoms and Signs of Vaginitis Observed in Pregnant Women

| Symptom or Sign | Total | Candidiasis | Trichomoniasis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Leucorrhea | 221 | 34.53 | 146 | 53.87 | 29 | 46.03 |

| Abdominal pain | 185 | 28.91 | 141 | 52.03 | 21 | 33.33 |

| Colpitis | 131 | 20.47 | 58 | 21.40 | 25 | 39.68 |

| Vulvar pruritus | 110 | 17.19 | 57 | 21.03 | 15 | 23.81 |

Figure 3.

Frequency of women with clinical vaginitis attended by the different hospitals.

As shown in Figure 4, of all samples, 42.3% (95% CI 38.5-46.1%) were positive for Candida albicans and 9.84% (95% CI 7.54-12.1%) were positive for Trichomonas vaginalis; 48.7% were negative for these infections. Only 6.41% of the samples gave inconclusive results using this latex agglutination test, not different from the observed percentage in the validation study (P > .05).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of samples showing positivity to Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis, as well as nonconclusive and negative samples.

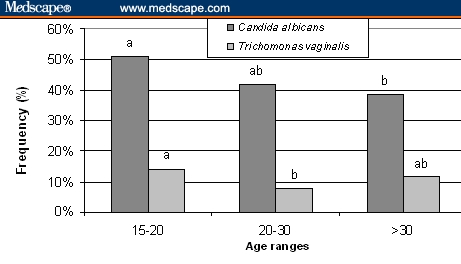

Candidiasis prevalence showed age-group variation (P < .05), decreasing with age. On the other hand, trichomoniasis prevalence was significantly different (P < .04) between the < 20 and 20-30 age groups, but not with the > 30 age group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Prevalence of candidiasis and trichomoniasis by age range. Different letters by agent, P < .05.

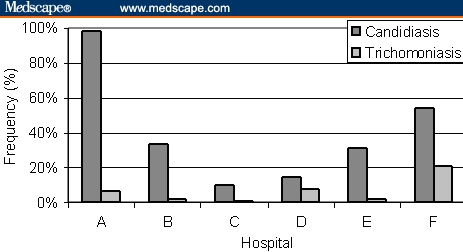

Differences were observed among hospitals in candidiasis prevalence (P < .001) (Figure 6). For example, in Hospital A, 97.8% of the samples were positive; in Hospital C, only 10.3% of the samples were positive. The prevalence values determined for the other hospitals were as follows: B 33.3%; D 14.3%; E 31.1%, and F: 53.9%. The prevalence of trichomoniasis also differed between hospitals (P < .001); whereas Hospital F had 20.9% positive cases, C had only 0.6%; A, 6.5%; B, 2.0%; D, 7.7%; and E 2.2%.

Figure 6.

Prevalence of samples showing positivity to Candida albicans and to Trichomonas vaginalis in the different hospitals. Differences P < .001 for both agents.

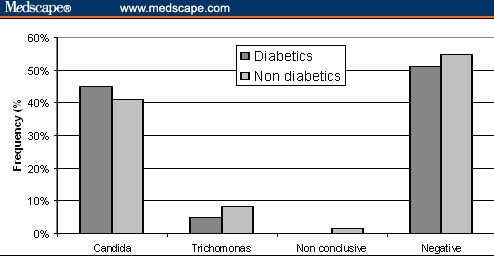

No differences in frequency of positive samples to Candida albicans and to Trichomonas vaginalis were observed between diabetic and nondiabetic women (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Frequency of samples showing positivity to Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis, as well as nonconclusive and negative samples in diabetic and nondiabetic pregnant women. No statistical difference was observed.

Discussion

The validation study of the kit showed similar specificity but higher sensibility to Candida albicans and to Trichomonas vaginalis compared with reported direct microscopic observations, for which sensibility values are around 40% for C albicans[20,21] and around 75%[20,22] for T vaginalis. Results obtained with a rapid nucleic acid hybridization test were very similar to the latex test in our hands, except with respect to the C albicans sensibility, for which present latex test showed higher values, ie, > 95% vs < 80%.[20]

That Hospital F was the most represented is a logical result, since it attends the most populated municipality of Havana. The distribution by age corresponds with the age in which most pregnancies occur in Cuba; pregnancy is very uncommon in females younger than 15 years or older than 40; most pregnancies occur in women between 20 and 35 years of age. Notably, at Hospital C, the average age of the pregnant women contributing samples was 2 years older than in the rest; this may reflect sociocultural characteristics of the population attended by this hospital.

In relation to the prevalence of the vaginal pathogens around the world, the high index of infection by Candida albicans we report agrees is consistent with that reported in other studies that have determined it to be the principal cause of vaginitis in Europe and the second most common after bacterial vaginosis in the United States.[23] The prevalence has also been reported to be high in specific regions, such as in the Mining Triangle of Brazil.[24]

In pregnant women, reports of several countries indicate the prevalence is around 20% (eg, 23% in Papua[25]; 19.2% in Brazil[26]; 20.8% in Poland[27]). However, in a review, Ferrer[16] cites prevalence values between 30% and 40%.

The prevalence of trichomoniasis we report is relatively high, given that some of the published literature indicates there has been a consistent decline globally.[1,2,5] However, results vary very widely from 0% to 34%.[7,9,11,12] Keeping in mind that this infection can be a cause of premature childbirth and indirectly a cause of newborn deaths, our findings confirm the necessity to increase measures against this infection during gestation -- including correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment as well as educating our population about these infections.[24]

Although we used a diagnostic tool that has much more sensitivity than the methods used in many of the referenced studies, other factors such as improper use of antibiotics, tropical climate, and sexual habits may contribute to the high prevalences we report.

With respect to candidiasis prevalence by age group, it was slightly higher in pregnant women younger than 20 years. This result corroborates findings of another report,[23,28] that age is not a factor that seriously affects candidiasis prevalence.

The differences we observed in prevalence of trichomoniasis by age range agree with findings of other studies.[2,29] It speaks to the fact that age is a risk factor for this infection in pregnant women < 20 years, perhaps due to poorly developed resistance among the very young. Together our data suggest a possible increase in vaginal immunity with age.

The observed differences between hospitals with respect to candidiasis and trichomoniasis prevalence reflect the same distribution pattern of women with clinical vaginitis, showing a correspondence between clinic and immunologic diagnosis.

Diabetes mellitus is a well-known risk factor for candidiasis. However, in this sample of pregnant women, no differences were observed in candidiasis and trichomoniasis prevalences between diabetic and nondiabetic women. We suggest that this may be due to the special care of diabetic pregnant women by the primary healthcare service in controlling their plasma glucose levels.[30]

Leucorrhea was the most commonly observed symptom in pregnant women who tested positive for both candidiasis and trichomoniasis; however, it was a symptom present in fewer than 50% of the women with positive samples. The other commonly but less detected symptoms in positive cases were abdominal pain, colpitis, and vulvar pruritus, confirming that clinical criteria are not very useful for diagnosis.[2,28]

We conclude that the immunologic method employed was valuable for vaginitis diagnosis, in particular for candidiasis and trichomoniasis. Prevalences of these infections in pregnant women of Havana for candidiasis was between 38.5% and 46.2% (95% CI) and for trichomoniasis was between 7.5% and 12.1% (95% CI).

Contributor Information

Dr Octavio Fernández Limia, Direction of Animal Health and Production, National Center for Animal and Plant Diseases, Carretera de Jamaica y Autopista Nacional, San José de las Lajas, La Habana, Cuba.

Dra María Isela Lantero, Ministry of Public Health, Direction of Epidemiology, STD/AIDS Programs; Lic. Arsenio Betancourt, National Center for Animal and Plant Diseases, Direction of Quality; Lic. Elizabeth de Armas, National Center for Animal and Plant Diseases, Direction of Animal Health and Production; Lic. Alejandra Villoch Cambas, National Center for Animal and Plant Diseases, Direction of Quality, San José de las Lajas, La Habana, Cuba.

References

- 1.Schenbach DA, Hillier SL. Advances in diagnostic testing for vaginitis and cervicitis. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:555-564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel JD. Vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1896-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global Prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections.2001. WHO/HIV_AIDS/2001.02 WHO/ CDS/ CSR/ EDC/ 2001.10. Available at http://www.emro.who.int/asd/backgrounddocuments/uae03/surv/stdoverview.pdf.

- 4.Berg AO, Heidrich FE, Fihn SD, et al. Establishing the cause of genitourinary symptoms in women in a family practice. Comparison of clinical examination and comprehensive microbiology. JAMA. 1984;251:620-625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monif GRG. Diagnosis of infectious vulvovaginal disease. Infect Med. 2001;18:532-533. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konje JC, Otolrin EO, Ogunniyi JO, Obisean KA, Ladipo AO. The prevalence of Gardenerlla vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Candida albicans in the cytology clinic at Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Sci. 1991;20:29-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirza NB, Nsanze H, D'Costa LJ, Piot P. Microbiology of vaginal discharge in Nairobi Kenya. Br J Vener Dis. 1983;59:186-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray A, Gulati AK, Pandey LK, Pandey S. Prevalence of common infective agents of vaginitis. J Commun Dis. 1989;21:241-244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart. G. Factors associated with trichomoniasis, candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis. Int J STD AIDS. 1993;4:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyarzún EE, Poblete AL, Montiel FA, Gutiárrez PH. Vaginosis bacteriana: diagnóstico y prevalencia. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 1996;64:26-35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera LR, Trenado MQ, Valdez AC, González CJC. Prevalencia de vaginitis y vaginosis bacteriqna: asociación con manifestaciones clïnicas, de laboratorio y tratamiento. Ginec y Obst Mex. 1996;64:2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi GG, Mendoza M. Incidencia de trichomoniasis vaginal en la consulta externa de ginecología. Boletín médico de Postgrado. 1996;12:34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toloi MRT, Franceschini SA. Exames colpocitológicos de rotina: Aspectos laboratoriais e patológicos. J Bras Ginec. 1997;107:251-254. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavalho AVV, Passos MRL. Perfil dos adolescentes atendidos no setor de DST da Universidade Fluminense em 1995. J Bras Doencas Sex Trans. 1998;10:9-19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara BMR, Fernandes PA, Miranda D. Diagnósticos citológicos cérvico- vaginais em laboratório de médio porte de Belo Horizonte- MG. RBAC. 1999;31:37-40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kent HL. Epidemiology of vaginitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1168-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrer, J. Vaginal candidiasis: epidemiological and etiological factors. Int J Gyn Obstet. 2000;71:521-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotch MF, Pastorek JG II, Nugent RP, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KCS, Esenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic and microbial and epidemiological associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferris DG, Hendrich J, Payne PM, et al. Office laboratory diagnosis of vaginitis: Clinician-performed test compared with a rapid nucleic acid hybridization test. J Fam Pract. 1995;41: 575-581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas L, Solano RS, Sinego IR. Frecuencia de trichomoniasis vaginal en mujeres supuestamente sanas. Rev Cubana Hig Epidemiología. 1999;37:2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Da Rosa MI, Rimel D. Factores asociados a candidiáse vulvovaginal, estado exploratorio. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2004;26:1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kent H. Epidemiology of vaginitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1168-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abad SJ, Vaz de Lima R, et al. Frequency of Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida sp and Gardnerella vaginalis in cervical-vaginal smears in four different decades. Sao Paulo Med J/Rev Paul Med. 2001;119:200-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klufio CA, Amoa BB, Delamare O, Hombhanje M, Kariwiga G, Igo J. Prevalence of vaginal infections with bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Candida albicans among pregnant women at the port Moresby General Hospital Antenatal Clinic. PNG Med J. 1995;38:163-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simoes JA, Giraldo PC, Faundes A. Prevalence of cervicovaginal infections during gestation and accuracy of clinical diagnosis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1998;6:122-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lisiak M, Klyszejko C, Pierzchalo T Marcinkowski Z. Vaginal candidiasis: frequency of occurrence and risk factors. Ginekol Pol. 2000;71:964-970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohbot JM. Les mycoses gánitales chroniques. Physiopathologie, traitement: jusqu'oú aller? Réalités en Ginécologie-Obstetrique. 1995;5:29-38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annual Report of Chief Medical Officer. Department of Health and Social Security, 1976-1984 (England and Wales).

- 30.de Leon EM, Jacober SJ, Sobel JD, Foxman B. Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal Candida colonization in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. MC Infectious Diseases. 2002;2:1. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/2/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]