Abstract

Background

The multilocus variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) technique has been developed for fine typing of many bacterial species. The genomic sequences of Neisseria meningitidis strains Z2491, MC58 and FAM18 have been available for searching potential VNTR loci by computer software. In this study, we developed and evaluated a MLVA method for molecular subtyping and phylogenetic analysis of N. meningitidis strains.

Results

A total of 12 VNTR loci were identified for subtyping and phylogenetic analysis of 100 N. meningitidis isolates, which had previously been characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing. The number of alleles ranges from 3 to 40 for the 12 VNTR loci; theoretically, the numbers of alleles can generate more than 5 × 1011 MLVA types. In total, 93 MLVA types were identified in the 100 isolates, indicating that MLVA is powerful in discriminating N. meningitidis strains. In phylogenetic analysis with the minimal spanning tree method, clonal relationships, established with MLVA types, agreed well with those built with ST types.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that the MLVA method has a higher degree of resolution than PFGE in discriminating N. meningitidis isolates and may be a useful tool for phylogenetic studies of strains evolving over different time scales.

Background

Neisseria meningitidis is one of the major causative agents of bacterial meningitis and septicemia in children and young adults [1]. Periodically, it causes large epidemics in Africa, especially in the sub-Saharan meningitis belt, and in Asia [1]; however, it is still a serious problem in many industrialized countries [2,3]. Occasionally, a meningococcal pandemic occurs after large population movements, such as pilgrimages [4,5].

Epidemiological studies of N. meningitidis, using various subtyping methods, allow the identification of a disease outbreak and investigation of the disseminating meningococcal strains. With the advent of molecular biology, a number of molecular methods have been developed for epidemiological studies of N. meningitidis. Among the methods, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) are the most frequently used subtyping techniques [6,7]. PFGE usually exhibits high discrimination for bacterial isolates, but it generates fingerprint image data that makes a comparison between laboratories difficult. In contrast, MLST is based on sequence data from seven conserved housekeeping genes; sequences that differ at even a single nucleotide are assigned to different alleles. The combination of alleles at the seven housekeeping genes is designated the sequence type (ST) of the isolate; numerous STs can be obtained. A Neisseria MLST database has been established that allows STs to be compared electronically via the Internet. STs are grouped into clonal complexes by their similarity to a central allelic profile (genotype). These central genotypes are identified by a number of heuristic means, including BURST and split decomposition, along with feedback from public health laboratories and epidemiologists. Once a central genotype has been identified, clonal complexes are defined as including any ST that matches the central genotype at four or more loci unless it more closely matches another central genotype [8]. The accumulation of nucleotide changes in housekeeping genes is a relatively slow process, and the allelic profile of a meningococcal strain is stable over time. Therefore, MLST is a powerful tool for study of global epidemiology of meningococci [6]. However, MLST provides lower discrimination than PFGE for fine typing of some clonal groups of N. meningitidis [9].

In recent years, the multilocus variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) technique has been developed for fine typing of many bacterial species [10-19]]. In addition, Yazdankhah et al. [20] have recently developed a MLVA method with four VNTR loci for genotyping of N. meningitidis isolates and successfully differentiated the serogroup W135 isolates from sporadic cases and outbreaks. In this study, we successfully developed a MLVA method with 12 VNTR loci to analyze a panel of N. meningitidis isolates, which had previously been characterized by PFGE and MLST.

Results

Identification of potential VNTR loci

Initially, 23 potential VNTR loci with short lengths of repeat units (≦ 30 bp) were selected from a list of repeat loci identified by the VNTRDB program at the three genomes of N. meningitidis strains Z2491, MC58 and FAM18. After evaluation with 10 genetically distinct N. meningitidis strains, 12 VNTR loci were then chosen for genotyping 100 N. meningitidis isolates. The remaining 11 VNTR loci were abandoned because multiple bands were produced or no PCR products were detected in all the 10 isolates. Four of the 11 loci were opa genes, which existed in multiple copies with various repeat numbers in Neisseria spp. [21]. Such loci were too complicated to be useful for MLVA genotyping. Among the 12 loci, three (NMTR1, NMTR9, NMTR12) have been characterized by Yazdankhah et al. [20]. Both VNTR06 and VNTR08 loci, described by Yazdankhah et al. [20], are actually the same locus equivalent to the NMTR9 locus described in this study. In the genomic sequence of N. meningitidis strain MC58, the primers VNTR06-F and VNTR06-R are at positions 286076–286057 and 285626–285649, and VNRT08-F and VNTR08-R at 285707–285726 and 286018–285999, respectively. Both primer sets amplify the same VNTR locus. The lengths of repeat units for the 12 repeat loci ranged from 4 to 30 bp, 7 of the 12 loci were multiples of 3 bp. NMTR12 is a compound tandem repeat with 12- and 13-bp repeat units arranging in variable numbers and sequences. This compound tandem repeat was verified by sequencing all the amplicons from 100 N. meningitidis isolates. Of the 12 loci, at least 9 were located in coding region of annotated genes (Table 1). The VNTRDB program used each of the three genomic sequences in turn as a "parent" sequence to search repeat loci and, then, located each of the loci at the other two genomes, so that a locus, for example NMTR9a with only one repeat unit in strains MC58 but with 2 repeat units in strain Z2491 and 3 repeat units in strain FAM18, could be found (Table 1).

Table 1.

VNTR locus characteristics at genomes of N. meningitidis strains Z2491, MC58 and FAM18.

| VNTR locusa | Consensus sequence(s) of repeat unitb | Length of repeat unit (bp) | Locus in Z2491 | Locus in MC58 | Locus in FAM18 | Function (Reference or locus_tagc) | |||

| Location | Number of repeat unit | Location | Number of repeat unit | Location | Number of repeat unit | ||||

| NMTR1 (VNTR01) | CAAACAA | 7 | 814844–815018 | 25 | 657240 – 657484 | 35 | 601072 – 601274 | 29 | glycosyl transferase [23] |

| NMTR2 | CATTTCT | 7 | 920757 – 920875 | 17 | 773274 – 773301 | 4 | 716022 – 716154 | 19 | Unknown |

| NMTR6 | GCTTCAGTTACAGCTTCTTTG | 21 | 1603619 – 1603660 | 2 | 1518318 – 1518359 | 2 | 1407985 – 1408068 | 4 | membrane protein (NMA1680) |

| NMTR7 | CAAG | 4 | 1638925 – 1638972 | 12 | 1556771 – 1556814 | 11 | 1444059 – 1444090 | 8 | hypothetical protein (NMB1507) |

| NMTR9 (VNTR06 & VNTR08) | GCCAAAGTT | 9 | 2158594 – 2158514 | 9 | 285906 – 285968 | 7 | 277433 – 277666 | 26 | rotamase (NMA2206) |

| NMTR9a | CCGCTGCTACTGCCGCTGCTGAAGCACCTG | 30 | 1100635 – 1100694 | 2 | 970825 – 970854 | 1 | 932818 – 932907 | 3 | dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase E2 component (NMA1150) |

| NMTR9b | TACGGCTGCCGCGTCAAA | 18 | 1385171 – 1385206 | 2 | 1293181 – 1293216 | 2 | 1191565 – 1191582 | 1 | murein hydrolase (NMA1488) |

| NMTR9c | CGGATACGCTCTTGG | 15 | 1446130 – 1446174 | 3 | 1353481 – 1353510 | 2 | 1250095 – 1250139 | 3 | hypothetical protein (NMA1547) |

| NMTR10 | CAGATT | 6 | 2058538 – 2058515 | 4 | 386427 – 386480 | 9 | 1824619 – 1824596 | 4 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase-β-chain (NMA0141) |

| NMTR12 (VNTR02) | a:GGGCTGTAGAGAT b: GGCTGTAGAGAT | 13, 12 | 1234098 – 1234135 | 3 = 2a1b | 1131164 – 1311531 | 29 = 20a9b | 1043723 – 1044023 | 24 = 13a11b | Unknown |

| NMTR18 | GGGTAGCGG | 9 | 2052950 – 2052967 | 2 | 392028 – 392045 | 2 | 1819003 – 1819047 | 5 | aldose 1-epimerase (NMA2099) |

| NMTR19 | CGTATTTTCCCAT | 13 | 2075417 – 2075442 | 2 | 369378 – 369403 | 2 | 1844470 – 1844534 | 5 | Unknown |

a Loci in parentheses have previouslybeen characterized by Yazdankhah et al.[20]

bNMTR12 is a compound tandem repeat locus with 12- and 13-bp repeat units, arranged in variable numbers and sequences.

cLocus tag in parentheses are based on gene annotation of N. meningitidis strain Z2491 (GenBank accession no. AL157959), except the NMTR7 locus, which is based on gene annotation of strain MC58 (GenBank accession no. AE002098).

MLVA genotyping

The MLVA genotyping was performed on 100 N. meningitidis isolates, which were collected between 1996 and 2002, and their PFGE patterns and ST types were characterized previously [9]. The results showed that the majority of the isolates carried only one copy of each of the 12 loci; however, five isolates carried extra copy of NMTR1, NMTR7, NMTR9 or NMTR18 locus, two isolates did not carry the NMTR1 locus, and three isolates did not carry the NMTR12 locus (Table 2). The number of alleles at each of the 12 loci ranged from 3 to 40 alleles counted on the 100 isolates analyzed (Table 3). Six loci (NMTR1, NMTR2, NMTR7, NMTR9, NMTR10 and NMTR12) had more than 10 alleles and four loci (NMTR1, NMTR2, NMTR7 and NMTR9) had a high allelic polymorphism index (≥ 0.9) (Table 3). Based on the allele number for each of the 12 loci determined in this study, at least 5 × 1011 MLVA allelic profiles (MLVA types) are expected.

Table 2.

ST, PFGE and MLVA genotypes for 100 N. meningitidis isolates.

| Strain code | Year of Isolation | Serogroup | ST codea | PFGE codea | MLVA code | MLVA allelic profileb (NMTR1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 9a, 9b, 9c, 10, 12, 18, 19) |

| ST-5 complex/Subgroup III | ||||||

| NM77 | 2001 | A | ST-7 | NMEN06.0065 | TW59 | 27, 14, 2, 3, 6, 1, 2, 4, 4, 22, 2, 2 |

| NM320 | 2002 | A | ST-7 | NMEN06.0066 | TW48 | 21, 17, 2, 3, 6, 1, 2, 4, 4, 23, 2, 2 |

| ST-11 complex/ET-37 complex | ||||||

| MS4527 | 1996 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW87 | 47, 8, 4, 11, 33, 2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 6, 5 |

| NM6 | 1996 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW76 | 37, 8, 4, 12, 37, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM7 | 1996 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW90 | 58, 8, 4, 17, 34, 2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 6, 5 |

| NM19 | 1997 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW92 | 33(34), 7, 4, 11, 33, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM24 | 1998 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW74 | 36, 7, 4, 15, 32, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| 2002-060 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW36 | 16, 7, 4, 10, 23, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM163 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW93 | 41(42), 8, 4, 9, 34, 3, 1, 3, 4, 25, 6, 5 |

| NM21125 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW77 | 37, 9, 4, 12, 32, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM64 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW79 | 38, 6, 4, 12, 35, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM66 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW58 | 27, 6, 4, 15, 39, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM76 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW83 | 39, 8, 4, 18, 34, 3, 1, 3, 4, 25, 6, 5 |

| NM79 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW72 | 35, 10, 4, 12, 32, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM80 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW57 | 27, 5, 4, 10, 37, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| 2002-059 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW78 | 38, 5, 4, 12, 36, 3, 1, 3, 4, 16, 6, 5 |

| NM181 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW81 | 38, 9, 4, 11, 29, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM25845 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW84 | 42, 6, 4, 21, 34, 3, 1, 3, 4, 23, 6, 5 |

| NM293 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW66 | 32, 9, 4, 12, 36, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM321 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW67 | 34, 9, 4, 12, 36, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM5 | 1996 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0056 | TW70 | 35, 6, 4, 10, 37, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM12 | 1997 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW80 | 38, 6, 4, 14, 37, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM14 | 1997 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW91 | 59, 7, 4, 15, 34, 2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 6, 5 |

| NM4967 | 1997 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW75 | 37, 6, 4, 15, 38, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM19172 | 2000 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW61 | 28, 5, 4, 13, 38, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM102 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW14 | 10, 10, 4, 9, 19(27), 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM152 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW82 | 39, 5, 4, 16, 37, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 6, 5 |

| NM357 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0057 | TW65 | 30, 7, 5, 25, 35, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 7, 5 |

| NM60 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0059 | TW71 | 35, 8, 4, 27, 35, 3, 1, 3, 4, 25, 6, 6 |

| NM68 | 2001 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0059 | TW86 | 43, 7, 4, 10(11), 25, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 3, 6 |

| NM257 | 2002 | W135 | ST-11 | NMEN06.0059 | TW88 | 49, 6, 4, 13, 24, 3, 1, 3, 4, 24, 3(6), 7 |

| NM81 | 2001 | C | ST-11 | NMEN06.0067 | TW25 | 11, 5, 4, 16, 27, 3, 1, 2, 4, 21, 6, 4 |

| NM377 | 2002 | C | ST-11 | NMEN06.0068 | TW52 | 24, 6, 4, 13, 24, 3, 1, 2, 4, 18, 4, 5 |

| NM378 | 2002 | C | ST-11 | NMEN06.0068 | TW52 | 24, 6, 4, 13, 24, 3, 1, 2, 4, 18, 4, 5 |

| NM25 | 1998 | W135 | ST-3016 | NMEN06.0058 | TW51 | 23, 7, 4, 9, 32, 2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 6, 5 |

| NM18972 | 2000 | W135 | ST-3016 | NMEN06.0058 | TW51 | 23, 7, 4, 9, 32, 2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 6, 5 |

| ST-23 complex/Cluster A3 | ||||||

| NM21468 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW3 | 4, 18, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM22034 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW3 | 4, 18, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM82 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW3 | 4, 18, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM25569 | 2002 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW7 | 4, 18, 5, 6, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM267 | 2002 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW5 | 4, 19, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM28225 | 2002 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0060 | TW5 | 4, 19, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM100 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0061 | TW6 | 4, 20, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM153 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0061 | TW8 | 4, 15, 5, 7, 10, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM21519 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0061 | TW4 | 4, 21, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM21675 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0061 | TW4 | 4, 21, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| NM25238 | 2001 | Y | ST-23 | NMEN06.0061 | TW11 | 5, 23, 5, 7, 9, 1, 2, 2, 11, 24, 2, 2 |

| ST-32 complex/ET-5 complex | ||||||

| NM159 | 2001 | B | ST-3465 | NMEN06.0042 | TW39 | 17, 8, 2, 12, 12, 1, 2, 3, 9, 26, 2, 3 |

| ST-41/44 complex/Lineage 3 | ||||||

| NM21700 | 2001 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0002 | TW85 | 40, 4, 2, 18, 10, 1, 1, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3 |

| NM25135 | 2001 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0002 | TW89 | 58, 4, 2, 11, 10, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 3 |

| 2002-075 | 2002 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0002 | TW18 | 10, 4, 2, 8, 10, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 3 |

| NM30607 | 2002 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0002 | TW73 | 36, 4, 2, 10, 13, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 3, 3 |

| NM20 | 1997 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0003 | TW23 | 11, 5, 2, 7, 12, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 3 |

| NM39 | 1999 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0004 | TW37 | 16, 8, 2, 12, 12, 1, 1, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3 |

| NM25614 | 2002 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0046 | TW34 | 15, 6, 2, 7, 12, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 4 |

| NM295 | 2002 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0046 | TW33 | 15, 6, 2, 8, 12, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 4 |

| NM9 | 1996 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0047 | TW17 | 10, 5, 2, 7, 14, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 3 |

| NM84 | 2001 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0047 | TW38 | 17, 7, 2, 10, 12, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 4 |

| NM40 | 1999 | B | ST-41 | NMEN06.0090 | TW41 | 18, 5, 2, 15, 16, 1, 1, 3, 4, 4, 2, 3 |

| NM21261 | 2001 | B | ST-154 | NMEN06.0001 | TW31 | 14, 8, 2, 11, 10, 1, 1, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3 |

| NM24481 | 2001 | B | ST-154 | NMEN06.0001 | TW46 | 20, 9, 2, 11, 10, 1, 1, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3 |

| NM8 | 1996 | B | ST-437 | NMEN06.0025 | TW63 | 28, 15, 2, 11, 9, 1, 1, 3, 8, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM18 | 1997 | B | ST-437 | NMEN06.0044 | TW55 | 26, 13, 2, 9, 8, 1, 1, 3, 8, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM32 | 1998 | B | ST-3466 | NMEN06.0031 | TW27 | 12, 6, 5, 8, 3, 1, 1, 3, 8, 4, 3, 2 |

| Hua443 | 2002 | B | ST-3468 | NMEN06.0048 | TW2 | 0, 16, 3, 15, 16, 1, 3, 3, 10, 3, 3, 3 |

| 2002-061 | 2002 | B | ST-3468 | NMEN06.0049 | TW1 | 0, 14, 3, 14, 16, 1, 3, 3, 9, 3, 3, 3 |

| ST-162 complex | ||||||

| NM420 | 2002 | B | ST-162 | NMEN06.0037 | TW42 | 18, 7, 2, 8, 13, 1, 2, 3, 25, 10, 3, 2 |

| ST-865 complex | ||||||

| NM15 | 1997 | B | ST-865 | NMEN06.0029 | TW64 | 29, 21, 2, 7, 22, 1, 1, 2, 10, 0, 2, 2 |

| NM272 | 2002 | B | ST-865 | NMEN06.0030 | TW56 | 26, 14, 2, 10, 21, 1, 1, 2, 11, 0, 2, 2 |

| ST-3129 group | ||||||

| NM2 | 1996 | B | ST-3129 | NMEN06.0020 | TW40 | 17, 13, 2, 8, 34, 1, 1, 2, 11, 8, 3, 2 |

| NM13 | 1997 | B | ST-3129 | NMEN06.0027 | TW69 | 34, 12, 4, 8, 16, 1, 1, 2, 10, 7, 3, 2 |

| ST-3200 group | ||||||

| NM21435 | 2001 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0005 | TW53 | 25, 11, 3, 8, 16, 1, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM71 | 2001 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0007 | TW28 | 13, 11, 3, 10, 15, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM30 | 1998 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0010 | TW50 | 22, 8, 3, 17, 15, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM88 | 2001 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0010 | TW35 | 15, 13, 3, 13, 13, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM397 | 2002 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0010 | TW49 | 22, 6, 3, 5, 12, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM10 | 1996 | B | ST-3200 | NMEN06.0012 | TW44 | 19, 8, 3, 13, 10, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM255 | 2002 | B | ST-3441 | NMEN06.0010 | TW62 | 28, 8, 3, 10, 16, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM256 | 2002 | B | ST-3441 | NMEN06.0010 | TW62 | 28, 8, 3, 10, 16, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM21992 | 2001 | B | ST-3469 | NMEN06.0006 | TW45 | 19, 7, 3, 9, 12, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM30088 | 2002 | B | ST-3470 | NMEN06.0013 | TW13 | 8, 8, 3, 10, 9, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM390 | 2002 | B | ST-3503 | NMEN06.0014 | TW21 | 10, 9, 3, 8, 9, 2, 1, 3, 8, 3, 2, 2 |

| NM26447 | 2002 | B | ST-4836 | NMEN06.0010 | TW68 | 34, 11, 3, 15, 13, 2, 1, 3, 8, 4, 2, 2 |

| ST-3439 group | ||||||

| NM62 | 2001 | B | ST-1393 | NMEN06.0093 | TW10 | 5, 34, 3, 13, 17, 1, 1, 3, 14, 5, 3, 2 |

| NM16 | 1997 | B | ST-3192 | NMEN06.0023 | TW16 | 10, 22, 3, 13, 14, 1, 1, 3, 15, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM30397 | 2002 | B | ST-3192 | NMEN06.0024 | TW22 | 10, 24, 3, 7, 16, 1, 1, 3, 14, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM383 | 2002 | B | ST-3192 | NMEN06.0024 | TW19 | 10, 20, 3, 13, 16, 1, 1, 2, 14, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM21 | 1997 | B | ST-3192 | NMEN06.0091 | TW20 | 10, 16, 3, 14, 15, 1, 1, 3, 14, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM22 | 1997 | B | ST-3192 | NMEN06.0092 | TW24 | 11, 21, 3, 10, 14, 1, 1, 3, 14, 4, 3, 2 |

| Nm15656 | 1999 | B | ST-3439 | NMEN06.0016 | TW9 | 5, 20, 3, 7, 14, 1, 1, 3, 15, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM38 | 1999 | B | ST-3439 | NMEN06.0017 | TW30 | 14, 20, 3, 13, 15, 1, 1, 3, 15, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM37 | 1999 | B | ST-3439 | NMEN06.0089 | TW15 | 10, 17, 3, 10, 13, 1, 1, 3, 18, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM4 | 1996 | B | ST-3440 | NMEN06.0022 | TW29 | 13, 16, 3, 10, 13, 1, 1, 3, 16, 4, 3, 2 |

| NM22208 | 2001 | B | ST-3442 | NMEN06.0015 | TW12 | 5, 30, 3, 10, 19, 1, 1, 3, 19, 4, 3, 2 |

| Single clonal lineage | ||||||

| NM3 | 1996 | B | ST-3175 | NMEN06.0021 | TW26 | 11, 15, 4, 7, 9, 1, 2, 3, 11, 31, 2, 2 |

| NM28 | 1998 | B | ST-3196 | NMEN06.0036 | TW54 | 26, 9, 5, 21, 24, 1, 1, 3, 33, 9, 3, 2 |

| NM90 | 2001 | NT | ST-3366 | NMEN06.0069 | TW32 | 14, 4, 2, 7, 6, 1, 1, 3, 16, 8, 3, 2 |

| NM15252 | 1999 | B | ST-3437 | NMEN06.0019 | TW47 | 20, 13, 2, 14, 7, 1, 1, 3, 8, 17, 2, 2 |

| NM25660 | 2002 | B | ST-3438 | NMEN06.0018 | TW43 | 18, 19, 2, 18, 12, 1, 2, 3, 16, 7, 2, 2 |

| NM412 | 2002 | B | ST-3504 | NMEN06.0050 | TW60 | 27, 20, 2, 15, 15, 4, 2, 2, 10, 0, 2, 2 |

aCharacterized previously [9].

b Number in parentheses indicates the second copy of the locus. The second allele indicated in the parentheses was ignored in the MST analysis.

Table 3.

Features of selected VNTR loci observed in 100 N. meningitidis isolates.

| Locus | Length of repeat unit (bp) | Size range of amplicon (bp) | Range of repeat unita | Number of allelesa | Polymorphism indexb |

| NMTR1 | 7 | 197–589 | 3–59 | 40 | 0.96 |

| NMTR2 | 7 | 236–446 | 4–34 | 23 | 0.92 |

| NMTR6 | 21 | 165–228 | 2–5 | 4 | 0.73 |

| NMTR7 | 4 | 195–291 | 3–27 | 18 | 0.9 |

| NMTR9 | 9 | 189–513 | 3–39 | 28 | 0.94 |

| NMTR9a | 30 | 188–278 | 1–4 | 4 | 0.6 |

| NMTR9b | 18 | 182–218 | 1–3 | 3 | 0.33 |

| NMTR9c | 15 | 187–217 | 2–4 | 3 | 0.35 |

| NMTR10 | 6 | 221–395 | 4–33 | 12 | 0.71 |

| NMTR12 | 13, 12 | 218–572 | 3–31 | 19 | 0.81 |

| NMTR18 | 9 | 182–227 | 2–7 | 6 | 0.67 |

| NMTR19 | 13 | 186–251 | 2–7 | 6 | 0.64 |

aNot including the unamplifiable allele at NMTR1 and NMTR12.

bNei's diversity index (DI) = 1 - ∑ (allele frequency)2

A total of 93 MLVA types were identified for the 100 isolates (Table 2). The majority of MLVA types represented only one isolate; however, each TW4, TW5, TW51, TW52, and TW62 types represented two isolates and TW3 represented three isolates. TW62 was identified in two serogroup B isolates (NM255 and NM256), which were obtained from two cases in a meningococcal disease outbreak in a family. TW52 was identified in two serogroup C isolates (NM377 and NM378) with a close epidemiological relationship. TW3, TW4, and TW5 were identified in serogroup Y isolates collected from sporadic cases; the isolates were derived from a newly imported clone [9]. The two serogroup W135 isolates with TW51 type were collected in cases at a 2-year interval.

As shown in the previous study [9], PFGE exhibited a higher degree of discrimination than MLST for the isolates analyzed. However, the results of this study showed that MLVA exhibited much higher resolution than PFGE on the same panel of isolates. MLVA discriminated all of the serogroup B isolates and 29 of 31 serogroup W135 isolates, which were collected from sporadic cases (Table 2). In contrast, only two ST type and four PFGE patterns were identified in the 31 serogroup W135 isolates (Table 2). Only one ST type and two PFGE patterns were identified in the 11 serogroup Y isolates (Table 2). However, these isolates were further discriminated into seven MLVA genotypes.

Phylogenetic analysis

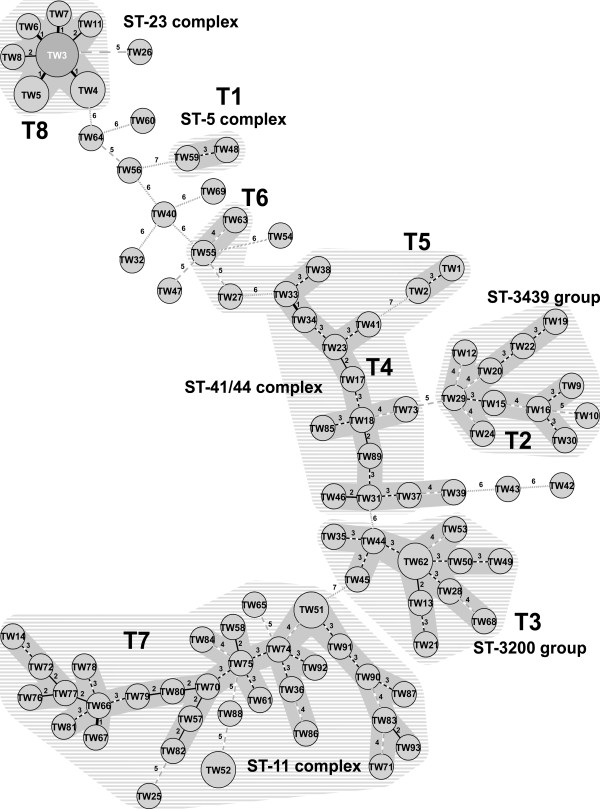

The clonal relationships among the 100 isolates were constructed with the MLVA types by the minimal spanning tree (MST) method. In the analysis with 12 loci, MLVA types matching at eight or more loci were regarded as clonally related. Consequently, eight distinct MLVA groups were established and the grouping feature established with the MLVA types had good agreement with that built with ST types (Figure 1). The two serogroup A isolates were characterized as different MLVA types (TW48 and TW59), differing in three loci, both carried ST-7 type within the ST-5 complex (Table 2). Similar to the results obtained from the previous MLST analysis, a complicated clonal relationship was found among the 52 serogroup B isolates. The majority of MLVA types were distributed in three major MLVA groups, T2, T3 and T4, and 13 types were regarded as single clonal lineages. T2 group comprised 10 MLVA types: isolates within this group and with TW10 (differing in five loci with the closest TW16 in T2 group) carried ST types belonging to the ST-3439 group. Similar to the T2 group, the T3 group comprised 11 MLVA types and all the isolates in this group belonged to the ST-3200 group. With the exception of TW39, isolates with the MLVA types within T4 group belonged to the ST-41/44 complex. In the MST analysis with ST types, some isolates were grouped in the ST-41/44 complex, but with MLVA allelic profiles they (TW1, TW2, TW27, TW55 and TW63) were separated from the T4 group. However, they had a closer genetic relationship with the genotypes within the T4 group.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree built with MLVA profiles. Minimum Spanning Tree diagram, consisting of 93 MLVA types are identified. Differences in loci between two MLVA types are numbered. Circle size is proportional to the number of isolates belonging to an MLVA type. Two or more MLVA types differing in four or less loci are regarded as a group. MLVA types in groups (T1 – T8) are marked in dark gray shadow and ST groups or ST complexes marked in light dashed lines.

All the MLVA types, except TW65 and TW88, representing the serogroup W135 isolates, were clustered in T7 group. The two MLVA types (TW25 and TW52), identified in three serogroup C isolates, had a closer clonal relationship with the W135 isolates than other serogroup isolates, although they differed at five loci with the closest MLVA types within the T7 group. A total of 32 MLVA types were identified in the 31 serogroup W135 and three serogroup C isolates; in contrast, only two ST types (ST-11 and its single locus variant, ST-3016) were found in the isolates (Table 2). The isolates with TW25 and TW52 types emerged in 2001 and 2002, respectively. Since TW25 and TW52 differed in as many as seven loci, the two MLVA strains should not be derived from a common imported strain.

The serogroup Y isolates shared a close clonal relationship as the seven MLVA types, forming a compact cluster. Six MLVA types differed in only one or two loci with the founder type, TW3, which was identified in the earliest collected isolates in Taiwan.

MLVA allelic profiles of isolates from patient-contact episodes

Five isolates, collected from healthy contacts of four patients were characterized by MLVA. The MLVA profiles were identical for isolates from three episodes. Two isolates from the fourth episode differed in a single locus, NMTR-7 (Table 4).

Table 4.

MLVA profiles of Neisseria meningitidis isolates from four patient/contact episodes.

| Patient/Contact | Sex | Age | Strain code | Year | Serogroup | MLVA code | MLVA profile (NMTR1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 9a, 9b, 9c, 10, 12, 18, 19) | |||||||||||

| Patient P1 | M | 0.3 | NM153 | 2001 | Y | TW8 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 24 | 2 | 2 |

| Contact of P1 | F | 29.3 | NM156 | 2001 | Y | TW8 | 4 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 24 | 2 | 2 |

| Patient P2 | M | 0.4 | Hua443 | 2002 | B | TW2 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Contact of P2 | F | 38.3 | Hua452 | 2002 | B | TW2 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient P3 | M | 5.3 | NM30397 | 2002 | B | TW22 | 10 | 24 | 3 | 7 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Contact of P3 | NA | 6.5 | NM30464 | 2002 | B | TW22 | 10 | 24 | 3 | 7 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Contact of P3 | NA | 34.3 | NM30465 | 2002 | B | TW22 | 10 | 24 | 3 | 7 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Patient P4 | F | 2.7 | NM25614 | 2002 | B | TW34 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Contact of P4 | F | 24.3 | NM25618 | 2002 | B | TW33 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

NA: Not available

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that the MLVA method is powerful for subtyping and useful for phylogenetic investigation of N. meningitidis isolates. The MLVA exhibited a much higher discriminatory power than PFGE for the isolates tested and the resulting data agreed well with the epidemiological observations. Of the 100 N. meningitidis isolates characterized, 96 were collected from sporadic cases with no apparently epidemiological links. This MLVA method with 12 VNTR loci discriminated, not only all the genetically diversified serogroup B isolates, but also exhibited a high degree of resolution for the serogroup W135 isolates. Although serogroup W135 meningococci emerged in Taiwan before 1996, only four PFGE patterns, sharing a high pattern similarity, were identified in the 31 isolates collected from 1996 to 2002 [9]. However, MLVA differentiated the 31 isolates into 30 genotypes. MLVA data also supported the belief that serogroup Y meningococci were derived from a recently emerging clone in Taiwan. Serogroup Y meningococci emerged for the first time in 2001 in Taiwan; the 11 isolates collected in 2001 to 2002 were tightly clustered together. The clustering feature supported the observation that the serogroup Y clone was recently introduced into this country. MLVA genotyping also showed that there were no a major epidemic N. meningitidis strain circulating in the country, where meningococcal disease was infrequent.

Our study showed that the clonal relationships between the isolates, established with MLVA types, was in good agreement with those built with ST types. As shown on Figure 1, strains within a ST complex or ST group shared more common VNTR loci. Among the 12 loci, four (NMTR1, NMTR2, NMTR7 and NMTR 12) were highly polymorphic; they could have higher variation rates. The remaining loci could have moderate and low variation rate. Thus, different sets of VNTR loci may be useful for phylogenetic investigation of isolates evolving over different time scales. Phylogenetic investigations of spreading of N. meningitidis strains over a long time scale will best be carried out using loci with a low or moderate variation rate. Forensics and outbreak investigations may use loci with a higher variation rate. In our study, the MST grouping features built with 10 or 11 loci, which excluded one or two highly polymorphic loci, such as NMTR1, NMTR2 or both from 12 loci, remained similar but tighter to that with 12 loci (data not shown). Therefore, use of more VNTR loci with a lower variation rate will increase the power of MLVA in phylogenetic studies of N. meningitidis strains evolving over a long time scale.

The allelic profiles of the 11 serogroup Y isolates demonstrated the level of stability for the 12 VNTR loci. The comparison of the allelic profiles indicated that VNTR2 had the highest variation rate; five additional alleles at NMTR2, but only one at NMTR1, NMTR7 and NMTR9, evolved in the serogroup Y isolates over a 2-year time span. The stability of the VNTR loci was also demonstrated by the comparison of the allelic profiles of isolates from four patient-contact episodes. Although a single locus variant was observed in isolates from a patient-contact episode (Table 4), this MLVA method should be stable enough for forensic and outbreak investigations. Since variation normally occurs in only a small portion of isolates from an outbreak [15], such variation is usually not a problem for interpretation of MLVA data.

The MLVA is useful for identification of outbreak strains. In our record, there was no serogroup C meningococcus identified in 1996–2000. A serogroup C isolate (with TW25 genotype) was identified for the first time in 2001 and two (TW52 genotype) in 2002. Although the three isolates differed in PFGE patterns, they had the same ST-11 type [9]. Therefore, the 2002 isolates were considered deriving from the 2001 strain. However, TW25 and TW52 differed in seven loci, including the high polymorphic loci (NMTR1, NMTR2, NMTR7, and NMTR9) and three moderate polymorphic loci (NMTR12, NMTR18 and NMTR19). MLVA profiles suggested that the two MLVA strains should not derive from a common imported strain. In contrast with, MLVA results suggested that the serogroup Y isolates were evolved from a newly imported clone; strains derived from the clone still caused infections in 2003 to 2005 with 2–3 patients a year.

To date, in our study and that of Yazdankhah et al. [20], a total of 12 VNTR loci have been characterized, and more could still exist in the genomes. For example, Jordan et al. [22] identified 22 coding tandem repeat loci that varied in numbers of repeat units between the three sequenced strains, of which only five loci were included in this study. Although the rest of the loci may have lower allelic polymorphism, they may be included in the VNTR set suitable for phylogenetic investigation of N. meningitidis strains.

Of the 12 loci, five were not with repeat units of multiples of 3 bp. However, it is not necessary that a repeat unit needs to be of multiples of 3 bp for having a biological function. For example, NMTR1 locus, having a 7-bp repeat unit, is located within the coding sequence of the glycosyltransferase (PglE) gene that involves in pilin glycosylation and phase variation [23]. Tandem repeat sequences or repeat sequence tracts are usually involved in diverse biological functions; to date, more than 100 repeat associated phase-variable genes in Neisseria spp. have been identified [21,22,24]. Repeat loci may locate within the coding region of a gene or in the non-coding region involved in gene regulation [24]. The biological function of NMTR2, NMTR12 and NMTR19 has not been elucidated. NMTR12 is a compound repeat locus with 12- and 13-bp repeat units; the two repeat units arranged in variable numbers and sequences. Further investigation is needed to explore the biological functions associated with these repeat loci.

Conclusion

MLVA exhibits a higher degree of resolution than PFGE for fine typing of N. meningitidis isolates and produces portable data that can easily be used for comparisons between laboratories via the Internet. MLVA data can also be used to investigate phylogenetic relationship between N. meningitidis strains. Therefore, MLVA can be adopted as an epidemiological tool for forensics and disease outbreak investigations, and for investigating clonal relationship among meningococcal strains. However, the mutation rate for each VNTR loci is still unknown. To fully exploit the value of MLVA, more VNTR loci need to be explored and more N. meningitidis isolates, of known epidemiological history, need to be characterized.

Methods

Identification of VNTR loci

The genomes of N. meningitidis strains Z2491 (GenBank accession no. AL157959), MC58 (GenBank accession no. AE002098) and FAM18 (obtained from The Welcome Trust Sanger Institute [25]), were explored for potential VNTR loci using unpublished VNTRDB computer software developed by Kao et al. in National Taiwan University. The program, which incorporates the algorithm of the Tandem Repeat Sequence Finder software [26], searches tandem repeat loci from one of the three genomic sequences and then locates the positions of each of the loci at the other two compared genomes. The three genomic sequences are used in turn as the "parent" sequence, so that a locus with only one repeat unit at a genome, but with two or more repeat units at other genomes, will not be missed. Searches found more than 300 repeat loci that were common to all the three strains and had variable repeat units between the three strains. Twenty-three repeat loci that had short repeat unit length (≤ 30 bp), more than 85% repeat sequence identity, and no indels were selected for further evaluation with 10 genetic distinct strains. Twelve loci, which were detected in all of the 10 testing isolates and amplified with only one amplicon, were chosen for genotyping of N. meningitidis isolates (Table 1).

Preparation of crude bacterial DNA

Meningococcal isolates, stored at -70°C, were plated onto trytic soy agar with 5% sheep blood and incubated overnight at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. A loopful (10 μl) of bacterial growth was removed from the plate, suspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) in an Eppendorf tube, and boiled for 10 min. After centrifugation at 3700 g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and used for PCR amplification.

PCR amplification and analysis of VNTR regions

The primer sets specific to the 12 VNTR regions are listed on Table 5. The primers were designed using the free program available at the Primer3 website [27]. A primer of each primer set was labeled on 5' end with an ABI-compatible dye, 6-FAM, NED, VIC or PET by the manufacture (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each 10-μl PCR mixture contained 1 × PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μM each primer, 200 μM each deoxyribonucleotide, 1.0 unit of the recombinant SuperNew Taq DNA polymerase (Jier Sheng Company, Taipei, Taiwan), and 1 μl of DNA template prepared as above-mentioned. The samples were placed on a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Applied BioSystems) and the PCR reaction was performed with a denaturing step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification step at 94°C for 30 s, at 54°C for 45 s, and at 72°C for 45 s, and by an extension step at 72°C for 10 min. Three microliters of each PCR products was electrophoresed in 2% SeaKem LE agarose (Cambrex Bio Science, Rockland, ME, USA) to check the sizes of amplified DNA products and the quality of PCR amplification.

Table 5.

VNTR locus-specific primers and the predicted sizes of amplicons from N. meningitidis strains Z2491, MC58 and FAM18.

| Locus | Primer designation | Primer sequence (5' → 3')a | Tm(°C) | Predicted size of amplicon (bp) | ||

| Z2491 | MC58 | FAM18 | ||||

| NMTR1 | NMTR-1 F | 6-FAM-GGGTCAAAAGACGGAAGTGA | 54.9 | 351 | 421 | 379 |

| NMTR-1 R | AAAATCATCCGAATCAATAAAGAC | 49.8 | ||||

| NMTR2 | NMTR-2 F | PET-GTGCGCCAGTAAGAAAATACAAT | 53.9 | 327 | 236 | 341 |

| NMTR-2 R | TCAGAAAAGTTTTGCATTTTGAA | 50.1 | ||||

| NMTR6 | NMTR-6 F | 6-FAM-GCGGCATCTTTCATTTTGTC | 52.8 | 165 | 165 | 207 |

| NMTR-6 R | CGAAGAAGCGAAAGACCAAG | 53.9 | ||||

| NMTR7 | NMTR-7 F | CCATCCTTATCCGAATCTGAA | 55 | 231 | 227 | 215 |

| NMTR-7 R | VIC-CTGAAACCCTGCCTGAAGAA | 53.4 | ||||

| NMTR9 | NMTR-9 F | PET-GGAAAGAATGATGAAAATCAAAGC | 51.3 | 243 | 225 | 396 |

| NMTR-9 R | CCGTCTGAAAAGCGGATACC | 55.8 | ||||

| NMTR9a | NMTR-9a F | GTTGTTGCCGACCAAGTTTT | 54.4 | 218 | 188 | 248 |

| NMTR-9a R | 6-FAM-GAACCTTGCAATGCGTTCAC | 55.2 | ||||

| NMTR9b | NMTR-9b F | CGACTTCATCGTCCACAAAA | 53 | 200 | 200 | 182 |

| NMTR-9b R | VIC-GGCTTTGTCTGCCTGTACG | 56.3 | ||||

| NMTR9c | NMTR-9c F | GGAAATCTGCGCTTTCGTAG | 54 | 202 | 187 | 202 |

| NMTR-9c R | NED-TCATGTCAGCAATTCCCTCA | 54 | ||||

| NMTR10 | NMTR-10 F | NED-GGCATCGATGATGTGAAACA | 53.3 | 221 | 251 | 221 |

| NMTR-10 R | GTGCTGAAGCACCAAGTGAA | 55.9 | ||||

| NMTR12 | NMTR-12 F | CAAAGAGAGAGTGGAAGAACATCA | 54.5 | 218 | 548 | 481 |

| NMTR-12 R | PET-AATGACGAAGAGTGGCAGGATT | 56.6 | ||||

| NMTR18 | NMTR-18 F | AACGGAAAATTCCTGCACAA | 53.1 | 182 | 182 | 209 |

| NMTR-18 R | VIC-CGTTTTCCGTGTTCCTGATT | 53.4 | ||||

| NMTR19 | NMTR-19 F | NED-GACATATTGTGCGATGTCGAG | 53.3 | 186 | 186 | 225 |

| NMTR-19 R | CGCCAACAGAAAAGAATACGA | 53.6 | ||||

a 6-FAM, VIC, NED and PET are ABI compatible dyes (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Before size analysis the fluorescent amplicons were diluted in water, usually at a 1:100 or 1:200 ratio, then separated by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer with GeneScan 500 LIZ Size Standard (cat # 4322682; Applied BioSystems). Data were collected and lengths of amplicons were determined with GeneScan Data Analysis Software, ver 3.7 (Applied BioSystems). All amplicons with different lengths from each locus were subjected to nucleotide sequence determination to verify the repeat sequence and the numbers of repeat units in the amplicons. The primers (without dye label) used for nucleotide sequence determination were the same as the primer sets used for PCR amplification. DNA sequencing was performed using the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit and an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer. The numbers of repeat units for the 12 VNTR loci (Table 1) and the predicted sizes of amplicons (Table 5) for the N. meningitidis strains Z2491, MC58 and FAM18 were taken as the standards to infer the number of repeat unit of each locus for the isolates tested.

Data analysis

The numbers of repeat units for each locus were saved as "Character Type" data in BioNumerics software (version 3.5; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) and then subjected to cluster analysis using the Minimum Spanning Tree method. The polymorphism information index or Nei's diversity index (DI) was calculated for evaluating allele diversity as 1-Σ (allele frequency)2.

Bacterial strains

A total of 105 N. meningitidis isolates, collected from meningitis patients and healthy contacts, were included in this study. The collection from patients comprised 2 serogroup A isolates, 52 serogroup B isolates, 3 serogroup C isolates, 31 serogroup W135 isolates, 11 serogroup Y and 1 non-groupable isolate (Table 2). They were collected from sporadic cases between 1996 and 2002 in Taiwan, except two pairs of isolates (NM255 and NM256; NM377 and NM378), which were, respectively, isolated from a meningococcal disease outbreak in a family and from two cases with a close temporal and spatial connection. All the 100 isolates from patients have been characterized by PFGE and MLST in a previous study by Chiou et al. [9]. Five isolates from healthy contacts were collected from four independent patient-contact episodes (Table 4).

Authors' contributions

JC Liao designed all the primers and MLVA analyzed all the isolates. CC Li was in charge of searching potential VNTR loci by computer software and MST clustering analyses. CS Chiou initiated and managed the project, analyzed data, and wrote the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants DOH94-DC-2025 and DOH95-DC-2021 from the Center for Disease Control, DOH, Taiwan.

Contributor Information

Jui-Cheng Liao, Email: jellyfish0819@so-net.net.tw.

Chun-Chin Li, Email: dls@cdc.gov.tw.

Chien-Shun Chiou, Email: nipmcsc@cdc.gov.tw.

References

- World Health Organization . Control of epidemic meningococcal disease. WHO Practical Guidelines. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization;; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard AJ, Scheifele D. Meningococcal disease and vaccination in North America. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:20–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoy AF, Dyet KH, Martin DR. Stability of PorA during a meningococcal disease epidemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:832–837. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.832-837.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PS, Harrison LH, Telzak EE, Ajello GW, Broome CV. Group A meningococcal carriage in travelers returning from Saudi Arabia. Jama. 1988;260:2686–2689. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.18.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa JR, Al Rabeah AM, Hajjeh R, Mustafa T, Fatani A, Al Bassam T, Badukhan A, Turkistani A, Makki S, Al Hamdan N, Al Jeffri M, Al Mazrou Y, Perkins BA, Popovic T, Mayer LW, Rosenstein NE. Serogroup W-135 meningococcal disease during the Hajj, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:665–671. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant DA, Feavers IM, Achtman M, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic T, Schmink S, Rosenstein NA, Ajello GW, Reeves MW, Plikaytis B, Hunter SB, Ribot EM, Boxrud D, Tondella ML, Kim C, Noble C, Mothershed E, Besser J, Perkins BA. Evaluation of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in epidemiological investigations of meningococcal disease outbreaks caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:75–85. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.75-85.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisseria MLST Home Page http://pubmlst.org/neisseria (accessed April 17, 2006).

- Chiou CS, Liao JC, Liao TL, Li CC, Chou CY, Chang HL, Yao SM, Lee YS. Molecular epidemiology and emergence of worldwide epidemic clones of Neisseria meningitidis in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Price LB, Klevytska AM, Smith KL, Schupp JM, Okinaka R, Jackson PJ, Hugh-Jones ME. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2928–2936. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2928-2936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuce RA, McCorry TP, McCarroll JF, Roring SM, Scott AN, Brittain D, Hughes SL, Hewinson RG, Neill SD. Discrimination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria using novel VNTR-PCR targets. Microbiology. 2002;148:519–528. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevytska AM, Price LB, Schupp JM, Worsham PL, Wong J, Keim P. Identification and characterization of variable-number tandem repeats in the Yersinia pestis genome. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3179–3185. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3179-3185.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow J, Smith KL, Wong J, Abrams M, Lytle M, Keim P. Francisella tularensis strain typing using multiple-locus, variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3186–3192. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3186-3192.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisse V, Houssu P, Hernandez E, Denoeud F, Hilaire V, Lisanti O, Ramisse F, Cavallo JD, Vergnaud G. Variable number of tandem repeats in Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica for typing purposes. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5722–5730. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5722-5730.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller AC, McEllistrem MC, Pacheco AG, Boxrud DJ, Harrison LH. Multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis distinguishes outbreak and sporadic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5389–5397. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5389-5397.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coletta-Filho HD, Takita MA, de Souza AA, Aguilar-Vildoso CI, Machado MA. Differentiation of strains of Xylella fastidiosa by a variable number of tandem repeat analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4091–4095. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.9.4091-4095.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouls LM, van der Heide HG, Vauterin L, Vauterin P, Mooi FR. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of Dutch Bordetella pertussis strains reveals rapid genetic changes with clonal expansion during the late 1990s. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5496–5505. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5496-5505.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Top J, Schouls LM, Bonten MJ, Willems RJ. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis, a novel typing scheme to study the genetic relatedness and epidemiology of Enterococcus faecium isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4503–4511. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4503-4511.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack AT, Dohnt MF, Symonds ML, Smythe LD. Development of a Multiple-Locus Variable Number of Tandem Repeat Analysis (MLVA) for Leptospira interrogans and its application to Leptospira interrogans serovar Australis isolates from Far North Queensland, Australia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2005;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdankhah SP, Lindstedt BA, Caugant DA. Use of variable-number tandem repeats to examine genetic diversity of Neisseria meningitidis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1699–1705. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1699-1705.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LA, Butcher SA, Saunders NJ. Comparative whole-genome analyses reveal over 100 putative phase-variable genes in the pathogenic Neisseria spp. Microbiology. 2001;147:2321–2332. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P, Snyder LA, Saunders NJ. Diversity in coding tandem repeats in related Neisseria spp. BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power PM, Roddam LF, Rutter K, Fitzpatrick SZ, Srikhanta YN, Jennings MP. Genetic characterization of pilin glycosylation and phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:833–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, van de Ven T, Mouchel N, Jeffries AC, Hood DW, Moxon ER. Experimentally revised repertoire of putative contingency loci in Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58: evidence for a novel mechanism of phase variation. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:245–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute http://www.sanger.ac.uk (accessed April 17, 2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primer3 http://frodo.wi.mit.edu (accessed April 17, 2006).